Proton therapy (PT) was first proposed by Robert R Wilson in 1946 because of the unique dosimetric property of proton beams known as the Bragg peak. In theory, a proton beam traversing a medium deposits a relatively small amount of radiation before it reaches the Bragg peak, and no radiation beyond it. The depth of the Bragg peak in the medium is determined by the energy of the protons. The dosimetric advantages of proton therapy (PT) treatment plans are demonstrably superior to photon-based external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for localized prostate cancer, but the reported clinical outcomes are similar.

- prostate

- proton therapy

- magnetic resonance imaging

1. Introduction

Treatment of patients with PT began around 1954 [4], but progress in the development of this modality has been slow due to numerous technical hurdles. Challenges for PT pioneers included the immaturity of the PT accelerator and dose-delivery systems in handling complex treatments, lack of knowledge on dosimetric properties such as the relative biological effectiveness (RBE) of proton beams, and lack of interest and incentive in the manufacturing industry to invest in developments of PT equipment [5]. This situation changed when the US Food and Drug Administration approved the clinical use of PT in 1988 [6], and the world’s first hospital-based PT system was established, at Loma Linda University Medical Center in California, in 1990. Since then, the number of hospital-based PT facilities has increased exponentially, with 104 PT treatment facilities operating globally by the end of 2021 and many more under construction and planning [7]. By the end of 2020, over 250,000 patients had been treated with PT worldwide [7]. Although prostate cancer has been one of the main treatment sites in PT, the practice has been controversial because of a lack of clinical evidence to justify the treatment cost [8]. Reported clinical outcomes in both local control and toxicity of PT for prostate cancer are similar to those for EBRT. The theoretical dosimetric benefits of PT have not translated to greater clinical benefits than EBRT for the prostate, as they have in other diseases sites, including pediatric malignancies of the central nervous system, large liver cancers, ocular melanomas, chordomas and chondrosarcomas [9][10]. The far-below-expected performance of PT in treatment outcomes in prostate cancer has been attributed to two main causes. First, the results of the randomized controlled Androgen Suppression Combined with Elective Nodal and Dose Escalated Radiation Therapy (ASCENDE-RT) trial [11] point to inadequate dose prescription, particularly in patients with high-risk disease, indicative of a dose–response characteristic of radiotherapy (RT) of the prostate. Second, improper dose delivery due to large uncertainties associated with the individual processes involved in PT and pre-treatment workflow may compromise the dose conformity of PT treatment, as demonstrated by robust planning [12]. The objectives of this review are twofold: (1) examine the underlying reasons behind the disappointing clinical outcomes in PT treatment of prostate cancer; and (2) investigate new PT technologies and innovative work procedures that are being implemented, how they may improve the accuracy and quality of PT treatment and facilitate a reduction in treatment margins, and the possibility of dose escalation to the appropriate level.

2. Potential Benefits of PT and Reported Clinical Outcomes of Prostate Treatments

3. Opportunities for Improvement with New Technologies and Innovative Techniques

-

The large uncertainties in CT HU values, and CT conversion to mass density or SPR [41]

| Clinical Scenarios |

|---|

- [38], can now be overcome by modern CT, which can acquire mass density maps or SPR directly [42] from CT image reconstruction data. Mass density and SPR are less sensitive to patient scan conditions than HU [43], and thus have less uncertainty. With this approach, the range uncertainty could be decreased from 3.5% to 2–2.5%. There is also an increasing interest in dual energy CT (DECT) as an alternative imaging modality for PT treatment planning because of its ability to discriminate between changes in patient density and chemical composition [44]. SPR calculation accuracy was found to be superior, on average, for DECT relative to single energy CT (SECT). Maximum errors of 12.8% and 2.2% were found in SPR data derived from SECT imaging and DECT imaging, respectively [44]. Quantitatively, the maximum dose calculation error in the SECT plan was 7.8%, compared to a value of 1.4% in the DECT plan [45]. Additionally, a novel spectral CT imaging technique based on a dual-layer detector-based approach has been used to demonstrate improvement in SPR prediction for particle therapy treatment planning, and would minimize the beam range uncertainty, allowing for the use of reduced safety margins in patient plans [46].

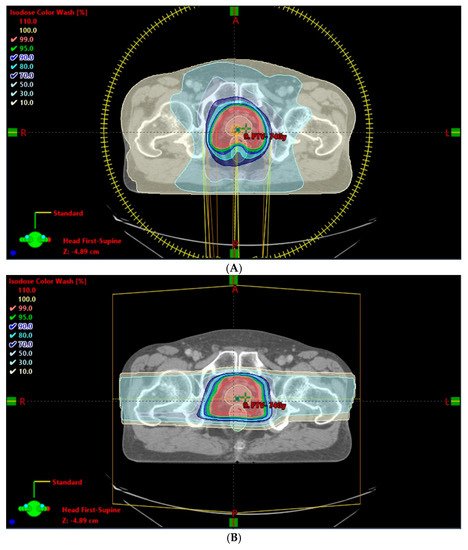

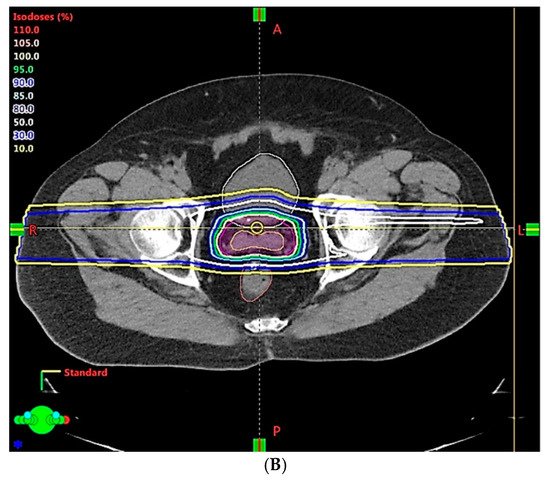

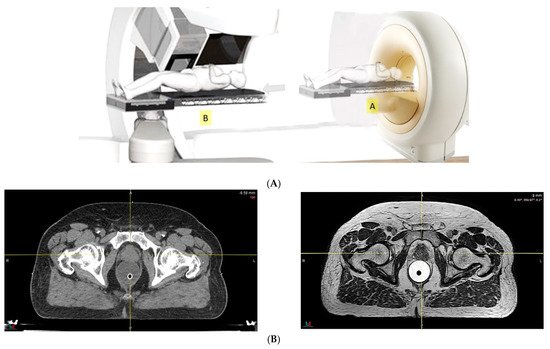

- Because of the inferior soft tissue contrast, orthogonal X-ray imaging systems rely on bony structures for verification of treatment position during patient setup. This type of setup technique can result in large positioning errors due to daily movement of the target and organs at risk (OARs) relative to the bony structures in the former technique. With fiducial markers implanted inside the prostate, many studies concluded that image registration by fiducial markers would reduce matching error. However, some patients may not accept marker implantation. Migration of markers with time may introduce registration errors. Such problems can now be minimized using on-board cone beam CT (CBCT). The better image quality of CBCT can provide 3D images and more information on the anatomic relationships between organs [47][48], which can be used to improve the accuracy of patient setup. Besides patient positioning, CBCT images can also provide information about inter-fractional changes in patient anatomy. In a recent study, an image-based correction method to generate pseudo-CT images from CBCT images was investigated for possible application in proton dose calculations [49] in adaptive PT. MRI, which has the ability to offer fast real-time imaging with high soft tissue contrast in the absence of ionizing radiation exposure [50], is being investigated for use in patient setup in RT. Our study using an external MRI setup room [51] and studies by others [52] indicated that patient positioning accuracy on the order of 1 mm is feasible, and is a significant reduction from that of conventional setup systems.

| Range uncertainty | 3.5% | 3.0% | 2.5% | 2.0% | 1.5% | 1.0% | |||

| Setup error | 5 mm | 3 mm | 2 mm | 1 mm | 1 mm | ||||

| CTV, V78Gy | 99.9% | 99.6% | 99.1% | 98.4% | 98.8% | 98.5% | 98.8% | 99.3% | 99.6% |

| Rectum, V70Gy | 30.8% | 25.9% | 24.5% | 20.1% | 19.7% | 20.1% | 18.2% | 19.5% | 19.5% |

| Bladder, V70Gy | 35.2% | 30.6% | 29.1% | 25.3% | 24.7% | 24.7% | 24.5% | 23.6% | 23.5% |

| Rectum, Dmean (Gy) | 37.1 | 33.3 | 32.4 | 28.8 | 28.5 | 28.9 | 27.1 | 28.4 | 28.5 |

| Bladder, Dmean (Gy) | 40.4 | 37.0 | 36.1 | 32.8 | 32.3 | 32.5 | 32.2 | 31.8 | 31.7 |

| Non-target tissue, Dmean (Gy) | 14.6 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 11.7 | 11.8 | 11.7 |

4. Conclusions

References

- Endo, M.; Robert, R.W. (1914–2000): The first scientist to propose particle therapy—Use of particle beam for cancer treatment. Radiol. Phys. Technol. 2018, 11, 1–6.

- Chera, B.S.; Vargas, C.; Morris, C.G.; Louis, D.; Flampouri, S.; Yeung, D.; Duvvuri, S.; Li, Z.; Mendenhall, N.P. Dosimetric study of pelvic proton radiotherapy for high-risk prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2009, 75, 994–1002.

- Rana, S.; Rogers, K.; Lee, T.; Reed, D.; Biggs, C. Dosimetric impact of Acuros XB dose calculation algorithm in prostate cancer treatment using RapidArc. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2013, 9, 430.

- Lawrence, J.H. Proton irradiation of the pituitary. Cancer 1957, 10, 795–798.

- Smith, A.R. Proton therapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006, 51, R491–R504.

- The National Association for Proton Therapy. Proton Therapy Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.proton-therapy.org/patient-resources/fact-sheet/ (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Particle Therapy Co-Operative Group. Available online: https://www.ptcog.ch/ (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Pan, H.Y.; Jiang, J.; Hoffman, K.E.; Tang, C.; Choi, S.L.; Nguyen, Q.-N.; Frank, S.J.; Anscher, M.S.; Shih, Y.-C.T.; Smith, B.D. Comparative toxicities and cost of intensity-modulated radiotherapy, proton radiation, and stereotactic body radiotherapy among younger men with prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1823–1830.

- Mohan, R.; Grosshans, D. Proton therapy—Present and future. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 109, 26–44.

- Schulz-Ertner, D.; Tsujii, H. Particle radiation therapy using proton and heavier ion beams. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 953–964.

- Morris, W.J.; Tyldesley, S.; Rodda, S.; Halperin, R.; Pai, H.; McKenzie, M.; Duncan, G.; Morton, G.; Hamm, J.; Murray, N. Androgen suppression combined with elective nodal and dose escalated radiation therapy (the ASCENDE-RT Trial): An analysis of survival endpoints for a randomized trial comparing a low-dose-rate brachytherapy boost to a dose escalated external beam boost for high- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017, 98, 275–285.

- Liu, W.; Mohan, R.; Park, P.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, R.; Sahoo, N.; Dong, L.; et al. Dosimetric benefits of robust treatment planning for intensity modulated proton therapy for base-of-skull cancers. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2014, 4, 384–391.

- Vargas, C.; Fryer, A.; Mahajan, C.; Indelicato, D.; Horne, D.; Chellini, A.; McKenzie, C.; Lawlor, P.; Henderson, R.; Li, Z.; et al. Dose–volume comparison of proton therapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2008, 70, 744–751.

- Mock, D.D.U.; Bogner, J.; Georg, D.; Auberger, T.; Pötter, R. Comparative treatment planning on localized prostate carcinoma. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2005, 181, 448–455.

- Cella, L.; Lomax, A.; Miralbell, R. Potential role of intensity modulated proton beams in prostate cancer radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2001, 49, 217–223.

- Moteabbed, M.; Trofimov, A.; Sharp, G.C.; Wang, Y.; Zietman, A.L.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Lu, H.-M. Proton therapy of prostate cancer by anterior-oblique beams: Implications of setup and anatomy variations. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 1644–1660.

- Cuaron, J.J.; Harris, A.A.; Chon, B.; Tsai, H.; Larson, G.; Hartsell, W.F.; Hug, E.; Cahlon, O. Anterior-oriented proton beams for prostate cancer: A multi-institutional experience. Acta Oncol. 2015, 54, 868–874.

- Polf, J.C.; Chuong, M.; Zhang, B.; Mehta, M. Anteriorly oriented beam arrangements with daily in vivo range verification for proton therapy of prostate cancer: Rectal toxicity rates. Int. J. Part. Ther. 2016, 2, 509–517.

- Murray, L.; Henry, A.; Hoskin, P.; Siebert, F.-A.; Venselaar, J. Second primary cancers after radiation for prostate cancer: A systematic review of the clinical data and impact of treatment technique. Radiother. Oncol. 2014, 110, 213–228.

- Davis, E.J.; Beebe-Dimmer, J.L.; Ms, C.L.Y.; Cooney, K.A. Risk of second primary tumors in men diagnosed with prostate cancer: A population-based cohort study. Cancer 2014, 120, 2735–2741.

- Royce, T.J.; Lee, D.H.; Keum, N.; Permpalung, N.; Chiew, C.J.; Epstein, S.; Pluchino, K.M.; D’Amico, A.V. Conventional versus hypofractionated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized noninferiority trials. Eur. Urol. Focus 2017, 5, 577–584.

- Al-Mamgani, A.; van Putten, W.L.; Heemsbergen, W.D.; van Leenders, G.J.; Slot, A.; Dielwart, M.F.; Incrocci, L.; Lebesque, J.V. Update of Dutch multicenter dose-escalation trial of radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2008, 72, 980–988.

- Dearnaley, D.P.; Jovic, G.; Syndikus, I.; Khoo, V.; Cowan, R.; Graham, J.; Aird, E.G.; Bottomley, D.; Huddart, R.A.; Jose, C.C.; et al. Escalated-dose versus control-dose conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Long-term results from the MRC RT01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 464–473.

- Kuban, D.A.; Tucker, S.L.; Dong, L.; Starkschall, G.; Huang, E.H.; Cheung, M.R.; Lee, A.K.; Pollack, A. Long-term results of the M. D. Anderson randomized dose-escalation trial for prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008, 70, 67–74.

- Beckendorf, V.; Guerif, S.; Le Prisé, E.; Cosset, J.-M.; Bougnoux, A.; Chauvet, B.; Salem, N.; Chapet, O.; Bourdain, S.; Bachaud, J.-M.; et al. 70 Gy versus 80 Gy in localized prostate cancer: 5-year results of GETUG 06 randomized trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Physics. 2011, 80, 1056–1063.

- Zietman, A.L.; Bae, K.; Slater, J.D.; Shipley, W.U.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Coen, J.J.; Bush, D.A.; Lunt, M.; Spiegel, D.Y.; Skowronski, R.; et al. Randomized trial comparing conventional-dose with high-dose conformal radiation therapy in early-stage adenocarcinoma of the prostate: Long-term results from Proton Radiation Oncology Group/American College of Radiology 95–09. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1106–1111.

- Sheets, N.C.; Goldin, G.H.; Meyer, A.-M.; Wu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Stürmer, T.; Holmes, J.A.; Reeve, B.B.; Godley, P.A.; Carpenter, W.R.; et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy, proton therapy, or conformal radiation therapy and morbidity and disease control in localized prostate cancer. JAMA 2012, 307, 1611–1620.

- Rodda, S.; Tyldesley, S.; Morris, W.J.; Keyes, M.; Halperin, R.; Pai, H.; McKenzie, M.; Duncan, G.; Morton, G.; Hamm, J.; et al. ASCENDE-RT: An analysis of treatment-related morbidity for a randomized trial comparing a low-dose-rate brachytherapy boost with a dose-escalated external beam boost for high- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 98, 286–295.

- Paganetti, H. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) values for proton beam therapy. Variations as a function of biological endpoint, dose, and linear energy transfer. Phys. Med. Biol. 2014, 59, R419–R472.

- Soukup, M.; Alber, M. Influence of dose engine accuracy on the optimum dose distribution in intensity-modulated proton therapy treatment plans. Phys. Med. Biol. 2007, 52, 725–740.

- Szymanowski, H.; Oelfke, U. Two-dimensional pencil beam scaling: An improved proton dose algorithm for heterogeneous media. Phys. Med. Biol. 2002, 47, 3313–3330.

- Titt, U.; Sahoo, N.; Ding, X.; Zheng, Y.; Newhauser, W.D.; Zhu, X.R.; Polf, J.C.; Gillin, M.T.; Mohan, R. Assessment of the accuracy of an MCNPX-based Monte Carlo simulation model for predicting three-dimensional absorbed dose distributions. Phys. Med. Biol. 2008, 53, 4455–4470.

- Petti, P.L. Evaluation of a pencil-beam dose calculation technique for charged particle radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 1996, 35, 1049–1057.

- Schaffner, B.; Pedroni, E.; Lomax, A. Dose calculation models for proton treatment planning using a dynamic beam delivery system: An attempt to include density heterogeneity effects in the analytical dose calculation. Phys. Med. Biol. 1999, 44, 27–41.

- Wouters, B.G.; Skarsgard, L.D.; Gerweck, L.E.; Cárabe-Fernández, A.; Wong, M.; Durand, R.E.; Nielson, D.; Bussière, M.R.; Wagner, M.; Biggs, P.; et al. Radiobiological intercomparison of the 160 MeV and 230 MeV proton therapy beams at the Harvard Cyclotron Laboratory and at Massachusetts General Hospital. Radiat. Res. 2015, 183, 174–187.

- Maeda, K.; Yasui, H.; Matsuura, T.; Yamamori, T.; Suzuki, M.; Nagane, M.; Nam, J.-M.; Inanami, O.; Shirato, H. Evaluation of the relative biological effectiveness of spot-scanning proton irradiation in vitro. J. Radiat. Res. 2016, 57, 307–311.

- Mairani, A.; Dokic, I.; Magro, G.; Tessonnier, T.; Bauer, J.; Böhlen, T.T.; Ciocca, M.; Ferrari, A.; Sala, P.; Jäkel, O.; et al. A phenomenological relative biological effectiveness approach for proton therapy based on an improved description of the mixed radiation field. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 1378–1395.

- Paganetti, H. Range uncertainties in proton therapy and the role of Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Med. Biol. 2012, 57, R99–R117.

- Thomas, S.J. Margins for treatment planning of proton therapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006, 51, 1491–1501.

- Royce, T.J.; Efstathiou, J.A. Proton therapy for prostate cancer: A review of the rationale, evidence, and current state. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2019, 37, 628–636.

- Chvetsov, A.V.; Paige, S.L. The influence of CT image noise on proton range calculation in radiotherapy planning. Phys. Med. Biol. 2010, 55, N141–N149.

- van der Heyden, B.; Öllers, M.; Ritter, A.; Verhaegen, F.; van Elmpt, W. Clinical evaluation of a novel CT image reconstruction algorithm for direct dose calculations. Phys. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 2, 11–16.

- Zhao, T.; Mistry, N.; Ritter, A.; Sun, B.; Li, H.; Mutic, S. Dosimetric evaluation of direct electron density computed tomography images for simplification of treatment planning workflow. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2016, 96, E674–E675.

- Bär, E.; Lalonde, A.; Royle, G.; Lu, H.-M.; Bouchard, H. The potential of dual-energy CT to reduce proton beam range uncertainties. Med. Phys. 2017, 44, 2332–2344.

- Zhu, J.; Penfold, S.N. Dosimetric comparison of stopping power calibration with dual-energy CT and single-energy CT in proton therapy treatment planning. Med. Phys. 2016, 43, 2845–2854.

- Faller, F.K.; Mein, S.; Ackermann, B.; Debus, J.; Stiller, W.; Mairani, A. Pre-clinical evaluation of dual-layer spectral computed tomography-based stopping power prediction for particle therapy planning at the Heidelberg Ion Beam Therapy Center. Phys. Med. Biol. 2020, 65, 095007.

- Landry, G.; Hua, C. Current state and future applications of radiological image guidance for particle therapy. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, e1086–e1095.

- Posiewnik, M.; Piotrowski, T. A review of cone-beam CT applications for adaptive radiotherapy of prostate cancer. Phys. Med. 2019, 59, 13–21.

- Thummerer, A.; Zaffino, P.; Meijers, A.; Marmitt, G.G.; Seco, J.; Steenbakkers, R.J.H.M.; Langendijk, J.A.; Both, S.; Spadea, M.F.; Knopf, A.-C. Comparison of CBCT based synthetic CT methods suitable for proton dose calculations in adaptive proton therapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 2020, 65, 095002.

- Wyatt, J.J.; Brooks, R.L.; Ainslie, D.; Wilkins, E.; Raven, E.; Pilling, K.; Pearson, R.A.; McCallum, H.M. The accuracy of Magnetic Resonance—Cone Beam Computed Tomography soft-tissue matching for prostate radiotherapy. Phys. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 12, 49–55.

- Businesswire. Hong Kong Sanatorium Radiotherapy Department and MedLever to Streamline Patient Setup & Imaging Process. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170913005133/en/Hong-Kong-Sanatorium-Radiotherapy-Department-and-MedLever-To-Streamline-Patient-Setup-Imaging-Process (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Nyholm, T.; Nyberg, M.; Karlsson, M.G.; Karlsson, M. Systematisation of spatial uncertainties for comparison between a MR and a CT-based radiotherapy workflow for prostate treatments. Radiat. Oncol. 2009, 4, 54.

- Hoffmann, A.; Oborn, B.; Moteabbed, M.; Yan, S.; Bortfeld, T.; Knopf, A.; Fuchs, H.; Georg, D.; Seco, J.; Spadea, M.F.; et al. MR-guided proton therapy: A review and a preview. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 15, 129.

- Oborn, B.; Dowdell, S.; Metcalfe, P.; Crozier, S.; Mohan, R.; Keall, P. Future of medical physics: Real-time MRI guided proton therapy. Med. Phys. 2017, 44, e77–e90.

- Depauw, N.; Keyriläinen, J.; Suilamo, S.; Warner, L.; Bzdusek, K.; Olsen, C.; Kooy, H. MRI-based IMPT planning for prostate cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 144, 79–85.

- Pepin, M.; Tryggestad, E.; Tseung, H.; Johnson, J.; Herman, M.; Beltran, C. A Monte-Carlo-based and GPU-accelerated 4D-dose calculator for a pencil-beam scanning proton therapy system. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 5293–5304.