Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 4 by Conner Chen and Version 3 by Conner Chen.

Gastric marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) of the stomach is a rare cancer type, often primarily treated with oral proton pump inhibitors, especially in Helicobacter pylori (Hp)-positive cases. However, the prevalence of Hp-unrelated gastric MZL has increased over the last two decades and 70-80% of Hp-negative gastric MZL are antibiotic-unresponsive. Radiation treatment can provide excellent local control in localized antibiotic-refractory gastric MZL.

- gastric marginal zone lymphoma

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- involved field

- involved site

- extended field

- radiation therapy

1. Introduction

Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) belongs to low-grade B-cell lymphomas [1]. It is the most common lymphoid neoplasm arising in the mucosa and was first described in 1983 by Isaacson [2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), three distinct, clinically different marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) entities have been described: extranodal MZL of MALT type (MALT lymphoma), splenic MZL, and nodal MZL [3]. Extranodal marginal zone lymphomas are most frequently located in the stomach (50–86% of all cases). The most important risk factor for gastric MZL is Helicobacter pylori infection [3].

The incidence of gastric MZL (gMZL) has been increasing, and most patients present with early-stage disease. Possibly, this may be influenced by the development of advanced endoscopic ultrasound [1][4][5][6].

In H. pylori positive gMZL, eradication using antibiotics to remove microenvironmental stimuli supporting tumor growth results in lymphoma regression in 55.6–84.1% of cases, and a long-term complete response in approximately 75% of cases [7][8]. For patients without the successful eradication of lymphoma, or with progressive disease, treatment options have historically included surgery, whereas the current treatment modalities are immunotherapy, chemotherapy (CTx), and radiation therapy (RT) [1][9][10][11].

The optimization of the treatment strategy for gMZL has a long history. Because of the rarity of gMZL (0.4 to 0.6 cases per 100,000 persons per year) [12], there are mainly retrospective studies reporting small patient numbers. These studies combine various types of gastric non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and employ different histologic classifications, staging systems, and forms of treatment.

Prior to the early 1990s, partial or total gastrectomy was the standard of care. This procedure is associated with significant morbidity and is currently rarely used as salvage treatment [13]. Despite the lack of evidence, the main concerns about using CTx and/or RT were gastric perforation or bleeding [2][14][15][16][17][18][19]. Over time, the information improved in favor of a solely organ-preserving therapy [14][15]. Early-stage disease patients treated with RT and/or CTx showed a low incidence of severe complications and a non-inferior outcome to Sx [14][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24].

The most effective single modality for local control (LC) of most types of lymphoma is radiation therapy. The history of RT in treating lymphomas shows one of the greatest successes in modern cancer treatment [25]. Because of the excellent LC compared to Sx, RT has been widely used and is internationally recommended as the therapy of choice in localized stages of lymphoma [9][26][27][28][29]. Depending on the subtype of lymphoma, the remission rates exceed 95%, but the recurrence rates increase with the length of the follow-up period. The recurrences are mainly localized or locoregional in the stomach or the duodenum [28][29][30].

From the 1960s to 1980s, the five-year overall survival rate using RT for gMZL was between 35 and 65% [15][16][31]. Currently, gMZLpatients do not usually die of their lymphoma, but reach roughly the mean life expectancy of the normal population. At 15 years post-treatment, the median age of a cohort of 178 patients (Yahalom et al.) was 78.5 years, and the life expectancy of the US population is 78.6 years [30].

In the past, extensive RT of the whole abdomen (WART) resulted in good local control, but also in worrisome long-term morbidity [32][33]. This prompted a renewed examination of extensive RT: reduced extended (red. EF) and involved field radiotherapy (IF), including only the initially involved regions, showed no inferior outcome to WART. The IFRT definitions were based on two-dimensional radiation therapy planned without the use of modern imaging, on bony landmarks, and on anatomical regions defined using the Ann Arbor Staging Classification system. However, although IFRT represented a significant reduction in the volume irradiated compared to the previously used EFRT, it still involved treating relatively large volumes of normal tissue, even in patients in the early stages of the disease. Today, the extensive RT fields of the past are no longer needed and the current internationally recommended treatment concept for the irradiation of gastric MZL lymphoma is an involved site radiotherapy (ISRT) with 24–30 Gy over 3 to 4 weeks [27][34][35][36] (Figure 1 and Figure 2; Table 1). Recent planning techniques attempt to further reduce the radiation dose in order to minimize the probability of normal tissue complication while maintaining tumor control [37].

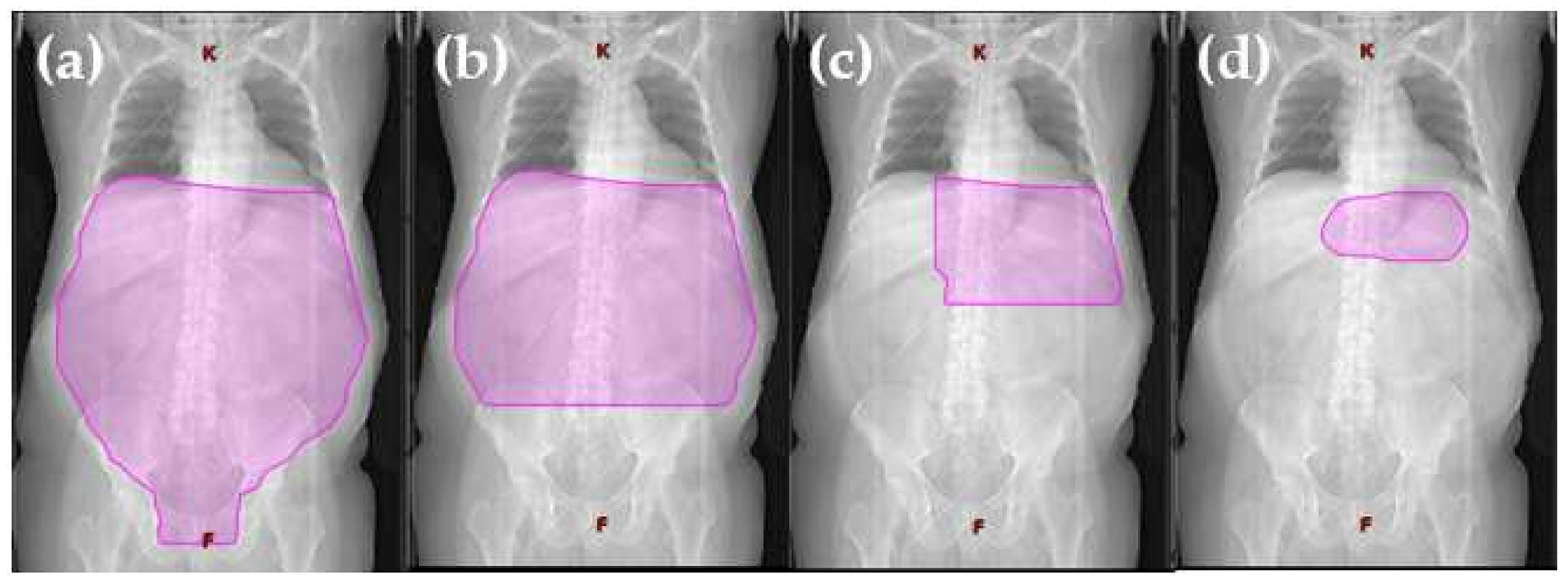

Figure 1. Visualization of radiation volume decrease from extended field to involved site radiotherapy. Definition of field sizes (a) Extended field (Burgers et al., 1988 [15]): the entire peritoneal cavity from the diaphragm to the pouch of Douglas and laterally to the side wall. (b) Reduced extended field (Willich et al., 2000 [38]): in the case of complete resection of a gastric tumor smaller than 5 cm in diameter, without submucosal perforation, the target volume was restricted to the upper and middle part of the abdomen, sparing the pelvis. (c) Involved field (Maor et al., 1990 [39]): the left upper quadrant (stomach, spleen, celiac, and paraaortic lymph nodes). (d) Involved site radiotherapy (ILROG guidelines Yahalom et al., 2015 [27]): the location is individualized to treat each patient’s stomach and nearby lymph nodes, which can contain microscopic or macroscopic disease, in a highly conformal way using 3D imaging.

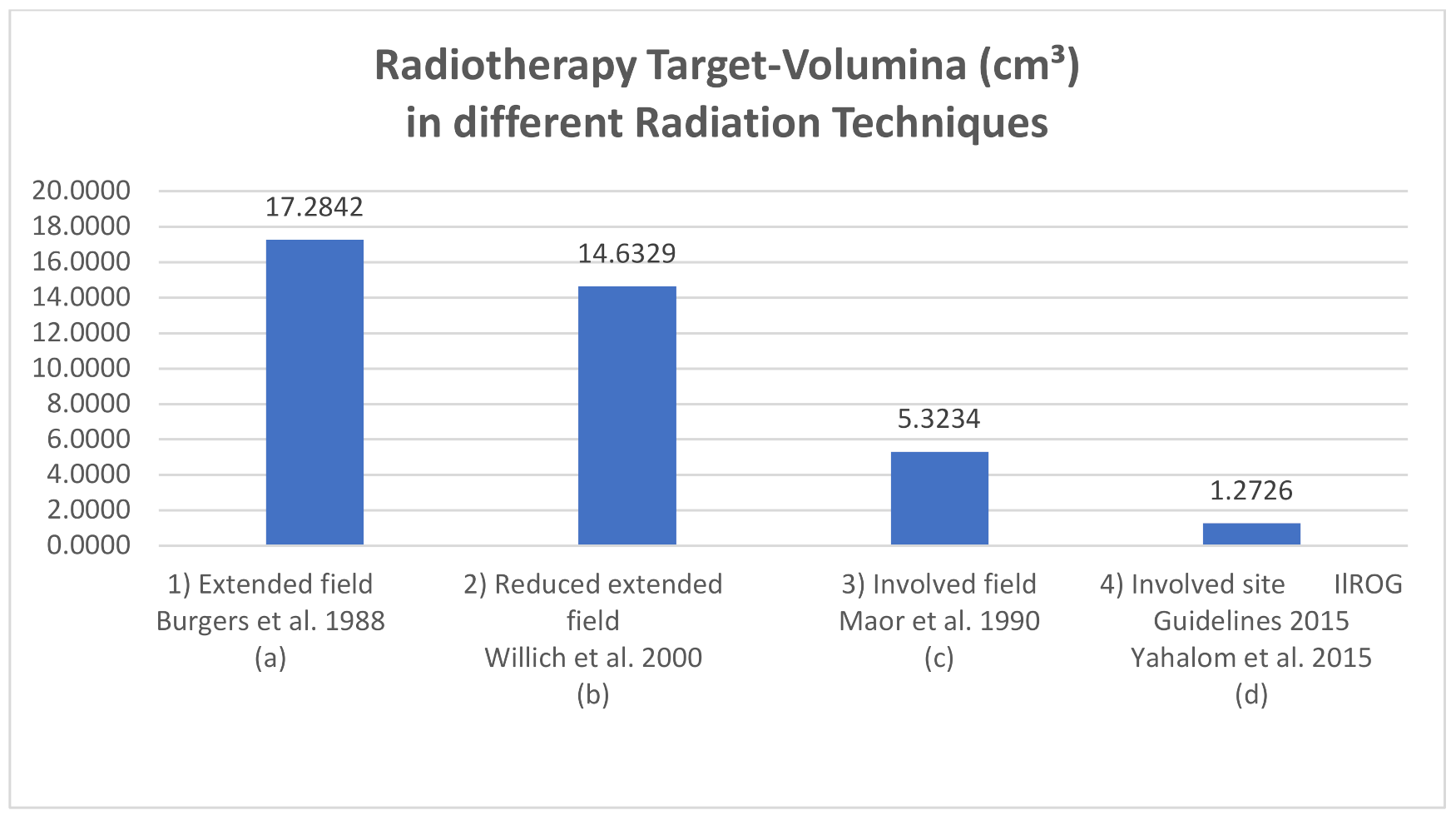

Figure 2. Exemplary RT-volume (cm3) in different radiation techniques measured with a 3D-radiation planning program. Definition of field sizes (a) Extended field (Burgers et al., 1988 [15]): the entire peritoneal cavity from the diaphragm to the pouch of Douglas and laterally to the side wall. (b) Reduced extended field (Willich et al., 2000 [38]): in the case of complete resection of a gastric tumor smaller than 5 cm in diameter, without submucosal perforation, the target volume was restricted to the upper and middle part of the abdomen, sparing the pelvis. (c) Involved field (Maor et al., 1990 [39]): the left upper quadrant (stomach, spleen, celiac, and paraaortic lymph nodes). (d) Involved site radiotherapy (ILROG guidelines Yahalom et al., 2015 [27]): the location is individualized to treat each patient’s stomach and nearby lymph nodes, which can contain microscopic or macroscopic disease, in a highly conformal way using 3D imaging.

Table 1. The development of total radiation doses for the treatment of gMZL from the 1990s to the present day.

| Publication Author | Publication Year | References | Study Nature | High Grade NHL Included in N | N | Radiation Dose (Gy) | Single Dose (Gy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taal | 1993 | [40] | Retrospective | No | 42 | 40 | 2.0 |

| Kocher | 1997 | [41] | Retrospective | No | 25 | 30–40 | 1.5–2.0 |

| Schechter | 1998 | [42] | Retrospective | No | 17 | median 30 (28.5–43.5) | 1.5 |

| Tsang | 2001 | [43] | Retrospective | No | 9 | median 25 (20–30) | 1.0–2.5 |

| Koch | 2001 | [14] | Prospective | Yes | 106 | 40 | 1.5–2.0 |

| Koch | 2005 | [44] | Prospective | No | 143 | 40 | 1.5–2.0 |

| Della Biancia | 2005 | [45] | Retrospective | No | 14 | 30 | Not available |

| Avilés | 2005 | [46] | Prospective | No | 78 | 40 | Not available |

| Watanabe | 2008 | [47] | Retrospective | No | 11 | 30 | 1.5 |

| Vrieling | 2008 | [48] | Retrospective | No | 115 | 40 | 1.0–2.0 |

| Tomita | 2009 | [49] | Retrospective | No | 20 | median 32 (25.6–50) | 1.5–2.2 |

| Ono | 2010 | [50] | Retrospective | No | 8 | 30 | 1.5 |

| Zullo | 2010 | [7] | Retrospective | No | 112 | median 30 (22.5–43.5) | 1.5–1.8 |

| Goda | 2010 | [51] | Retrospective | No | 25 | median 30 (17.5–35) | 2.5 |

| Fischbach | 2011 | [52] | Prospective | No | 19 | 46 | 1.8–2.0 |

| Wirth | 2013 | [53] | Retrospective | No | 102 | median 40 (26–46) | median 1.8 |

| Abe | 2013 | [54] | Retrospective | No | 34 | 30 | 1.5–2.0 |

| Teckie | 2015 | [29] | Retrospective | No | 123 | median 30 (Range unknown) | 2.0 |

| Ruskone-Fourmestraux | 2015 | [55] | Prospective | No | 232 | 30 | 2.0 |

| Ohkubo | 2017 | [56] | Retrospective | No | 27 | median 30 (30–39.5) | 1.5 |

| Pinnix | 2019 | [57] | Retrospective | No | 32 | median 30 (24–36) | 1.5 |

| Reinartz | 2019 | [28] | Prospective | No | 290 | median 40 (36–44) | 1.8–2.0 |

| Yahalom | 2021 | [30] | Retrospective | No | 178 | median 30 (22.5–43.5) | 1.5 |

| Saifi | 2021 | [58] | Retrospective | No | 42 | median 30 (23.5–36) | 1.5–2.0 |

2. Extended Field Radiotherapy (EFRT)

The treatment of gastric lymphoma with radiation therapy alone has been documented in the medical literature since the 1930s [59]. In 1939, Archer [59] reported on twenty gastric lymphosarcoma patients surviving 5 years after diagnosis. Eight patients were treated with biopsy and radiation alone, although this approach was commonly performed in patients with inoperable tumors.

Advances in technology enabled RT to treat large volumes, and extended field RT (EFRT), with prophylactic treatment of the entire abdomen, became the treatment of choice, thereby increasing disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) rates [40][41][59][60][61][62][63]. Pathophysiologically, it was justified by dealing with the normal flow of the intraperitoneal fluid. Since the fluid reaches the pouch of Douglas and flows back up to the diaphragm, the gastrectomy would cause loose tumor cells to spread throughout the abdomen. The proliferation and dissemination of such cells can be prevented by whole abdominal radiotherapy (WART) [15]. Therefore, the radiation field encompassed the entire abdominal cavity in the longitudinal direction from the diaphragm to the pouch of Douglas and in transverse direction to the side wall, with dorsal shielding from the right kidney [15]. The boost covered the entire stomach, the paraaortic area to the level of L2–L3, depending on the location of the stomach, which was determined using barium meal pictures in the treatment position [21] (Figure 1a).

Most protocols used WART for primary or postoperative therapy of gastric lymphoma to a total dose of 20–30 Gy, with a sequential boost to the entire stomach bed and paraaortic node region of 40–45 Gy. Using EFRT, some studies demonstrated a survival advantage for postoperative radiation therapy [16][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71]. Bush and Ash [66] found that WART at 25 Gy yielded a 2-year no evidence of disease survival (NED)rate of 64%, and a 2-year LC rate of 82%, compared with 44% and 36% for patients treated with resection only, respectively. Herrmann [65] applied WART at 20 Gy, followed by a boost to the stomach bed and paraaortic lymph node region, noting an 80% 5-year NED for patients solely treated with irradiation, 50% for patients solely resected, and 90% for patients with combined treatments. Similarly, Shiu [64] used WART at 25 Gy and boosted the gastric bed to 40 Gy. The five-year survival rate was 33% for patients solely resected, 67% for patients receiving postoperative irradiation, and 85% for those receiving more than 30 Gy.

In 1988, Burgers et al. [15] reported on 24 stage I gastric NHL patients who were treated with irradiation alone. The RT consisted of a three-week WART treatment at 20 Gy, followed by an additional two-week treatment at 20 Gy with a boost at 40 Gy. After a median follow-up of 48 months, the 4-year DFS was 83%.

General prophylactic containment of the inguinal lymph nodes in the case of WART does not appear to be necessary [63].

When Fischbach [72] showed that the postoperatively irradiated patients had comparable chances of survival despite unfavorable selection criteria, such as incomplete resection, advanced stage, and other risk factors, a prospective study was carried out.

EFRT with boosts was used in the first prospective, multicenter study, GIT NHL 01/92, initiated at the University Hospital of Muenster, Germany [14][24][65]. Whether or not the treatment included surgery was at the discretion of each participating center. After resection, patients with low-grade or indolent histological subtypes of lymphoma in stages IE and IIE were treated with WART (30 Gy) and, in case of residual disease, an additional boost with 10 Gy was used. Without gastric resection, stage IE and IIE patients received EFRT (30 Gy + 10 Gy boost) using AP/PA opposing fields with individual shielding of the kidneys and of right lobe of the liver. There were no significant differences in survival rates between patients who were resected or solely irradiated as part of their treatment. From this point on, gastrectomy was no longer integrated into the standard therapy. Currently, in gMZL, surgical management is only necessary in the case of emergency indications, such as macroscopic bleeding or perforation.

3. Reduced Extended Field Radiotherapy

Shimm et al. showed that the size of the radiation fields can be reduced without affecting the prognosis in mixed gastric lymphoma. In their retrospective analysis, 19/26 patients with primary gastric lymphoma received postoperative radiation therapy. The AP-PA fields covered the gastric bed and the regional nodes (mean size, 323 cm2; 19 cm × 17 cm) (Figure 1). The mean dose was 36 Gy à 1.5–2.0 Gy and the 5-year OS was 58%. Three patients who received postoperative radiation therapy had abdominal failures comparable to those receiving a previous series of WART radiation therapy [71].

In accordance, Lim found that after surgery, radiation treatment at 20–30 Gy of the gastric bed and para-aortic lymph nodes improved LC from 90% to 100% in mixed gastric lymphomas [73].

In the prospective multicenter study GIT NHL 02/96 of stage I and stage II primary GI lymphomas [38][44], the aim was to de-escalate treatment. The radiation dose was 30 Gy, followed by a 10 Gy boost to the tumor region if the resection was not complete. The radiotherapy volume of patients with indolent lymphoma stage I and microscopic (R1) or macroscopic (R2) residuals after gastric resection [74] included the upper and middle part of the abdomen. The lower field boundary was the fifth lumbar vertebra (as reduced extended-field radiotherapy (red. EF), (30 Gy + 10 Gy boost to R1 or R2 regions), (Figure 1b). After complete resection, patients with stage II disease were treated with red. EF 30 Gy, while after incomplete resection (R1 or R2), the target field was a WART with 30 Gy, followed by a boost of 10 Gy to the gastric region. Non-resected patients were also treated with red. EF with 30 Gy in stage I and with WART 30 Gy in stage II. The tumor region was boosted with 10 Gy. It should be emphasized that no disadvantage could be observed with the use of an organ-preserving treatment (OS at 42 month was 86% with surgery vs. 91% without surgery; the 5-year EFS was 70%) [44]. In a prospective trial conducted by Avilés et al., 241 patients with early stage gMZL were randomized to receive surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. In the radiotherapy group, 30 Gy was administered using WART, with the liver and kidneys shielded. The upper abdomen treatment was boosted to 40 Gy. EFS after 10 years was 52% in the radiotherapy arm, 52% with surgery, and 87% in the chemotherapy group. However, the overall survival rate showed no significant differences between the three groups [46].

4. Involved Field Radiation Therapy (IFRT)

Maor et al. reported on a series of 34 patients with stages IE and IIE gMZL who were treated with conservative treatment alone, consisting of chemotherapy in combination with involved field radiotherapy (IFRT). The chemotherapy consisted of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone and bleomycin (CHOP-Bleo); or cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, etoposide, and dexamethasone (CMED). IFRT was started after four cycles of chemotherapy; the irradiation field included the left upper quadrant (stomach, spleen, celiac, and paraaortic lymph nodes), (Figure 1c). The total dose was 30 Gy to 50 Gy at 1.8 Gy/day. A dosage exceeding 40 Gy was delivered to a reduced field that addressed the lymphoma in the stomach. Additionally, up to eight cycles of chemotherapy were administered. The 5-year OS rate was 73% and the DFS rate was 62% [39].

The successful treatment of gMZL with radiation alone at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center was first announced in 1998 [42] and included 51 patients with H. pylori–independent gMZL [10][42]. The patients received 30 Gy (28.5–43.5 Gy) in 1.5-Gy doses for a period of 4 weeks to the stomach and the local lymph nodes (low dose IFRT) using opposed anterior and posterior fields. An oral (2%) barium sulfate suspension and inspiration and expiration radiographs were used to aid in localizing the stomach, and an intravenous pyelogram was used to locate the kidneys. To include the gastric lymph nodes in the treatment volume, a 2 cm margin around the gastric wall was added.

The 5-year freedom-from-treatment failure and the overall survival rates were 89% and 83%, respectively. The cause-specific survival was 100%.

In the German multicenter prospective trial DSGL 01/2003, RT was stratified according to the stage of disease, and stage IE was treated with IFRT and IIE with red. EF. In the area of the tumor, a dose of 40 Gy was applied and 30 Gy in case of the prophylactic extended area in the red. EF, using two-dimensional (2D) opposed radiation fields or three-dimensional (3D) conformal radiotherapy (CRT) [28].

5. Involved Site Radiotherapy (ISRT)

Modern advanced computed tomography (CT) imaging and highly conformal radiation therapy planning and delivery are currently used in patients with gMZL. Unlike most solid tumors, it is not necessary to irradiate the stomach with high doses of radiation, but rather to minimize the dose of radiation to normal tissues, as experience has shown that even relatively low doses cause significant long-term morbidity and mortality.

Current target volume and radiation dose guidelines for involved site RT (ISRT) are provided by the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group (ILROG), a worldwide organization established in 2011 supporting the research on RT for lymphoma [27].

To date, no randomized trials comparing ISRT with IFRT have been published. It is unlikely that such studies will be conducted because, due to the low recurrence and side effect rates, a very high number of patients would have to be recruited in order to prove non-inferiority.

Rather than using the standard treatment fields of the past, ISRT is being individualized to treat each patient’s stomach and nearby lymph nodes, which may contain microscopic or macroscopic disease, in a highly conformal way using 3D imaging (Figure 1d). The ISRT concept has been accepted as the standard for modern RT for gMZL by most centers and collaborative groups, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [76].

The clinical treatment volume (CTV) for gMZL includes the stomach and first part of the duodenum. Perigastric lymph nodes and other parts of the duodenum are also included in the clinical treatment volume if they are involved by disease. Using this target volume, the irradiated volume is significantly smaller than the volume used in the old IFRT technique [27] (Figure 1a–d).

Excellent outcome has been demonstrated with ISRT using pre-defined target volume (PTV) and 30 Gy for treatment planning [30][54][55][57][77]. The highest 5-year and 10-year overall survival rates reported to date were 94% and 79%, respectively, comparable to the general population [22].

Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) with reduced dosage was used effectively in a recent series of 32 gMZL patients. The dose reduction to 24 Gy showed no disease failure 2 years after ISRT. The clinical target volume (CTV) for ISRT included the stomach alone for stage I or the stomach and involved lymph nodes for stage II, each with a safety margin of 2–3 cm [57].

References

- Zucca, E.; Bergman, C.C.; Ricardi, U.; Thieblemont, C.; Raderer, M.; Ladetto, M. Gastric marginal zone lymphoma of MALT type: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, vi144–vi148.

- Isaacson, P.; Wright, D.H. Extranodal malignant lymphoma arising from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Cancer 1984, 53, 2515–2524.

- Wotherspoon, A.; Diss, T.; Pan, L.; Isaacson, P.; Doglioni, C.; Moschini, A.; De Boni, M. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet 1993, 342, 575–577.

- Severson, R.K.; Davis, S. Increasing incidence of primary gastric lymphoma. Cancer 1990, 66, 1283–1287.

- Capelle, L.; de Vries, A.; Looman, C.; Casparie, M.; Boot, H.; Meijer, G.; Kuipers, E. Gastric MALT lymphoma: Epidemiology and high adenocarcinoma risk in a nation-wide study. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 2470–2476.

- Dreyling, M.; Thieblemont, C.; Gallamini, A.; Arcaini, L.; Campo, E.; Hermine, O.; Kluin-Nelemans, J.C.; Ladetto, M.; Le Gouill, S.; Iannitto, E.; et al. ESMO Consensus conferences: Guidelines on malignant lymphoma. Part 2: Marginal zone lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 857–877.

- Zullo, A.; Hassan, C.; Cristofari, F.; Andriani, A.; De Francesco, V.; Ierardi, E.; Tomao, S.; Stolte, M.; Morini, S.; Vaira, D. Effects of Helicobacter pylori Eradication on Early Stage Gastric Mucosa–Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 8, 105–110.

- Stathis, A.; Chini, C.; Bertoni, F.; Proserpio, I.; Capella, C.; Mazzucchelli, L.; Pedrinis, E.; Cavalli, F.; Pinotti, G.; Zucca, E. Long-term outcome following Helicobacter pylori eradication in a retrospective study of 105 patients with localized gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 1086–1093.

- Ruskone-Fourmestraux, A.; Fischbach, W.; Aleman, B.M.P.; Boot, H.; Du, M.Q.; Megraud, F.; Montalban, C.; Raderer, M.; Savio, A.; Wotherspoon, A.; et al. EGILS consensus report. Gastric extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT. Gut 2011, 60, 747–758.

- Schechter, N.R.; Yahalom, J. Low-grade MALT lymphoma of the stomach: A review of treatment options. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2000, 46, 1093–1103.

- Fischbach, W.; Goebeler, M.E.; Ruskone-Fourmestraux, A.; Wundisch, T.; Neubauer, A.; Raderer, M.; Savio, A.; EGILS (European Gastro-Intestinal Lymphoma Study) Group. Most patients with minimal histological residuals of gastric MALT lymphoma after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori can be managed safely by a watch and wait strategy: Experience from a large international series. Gut 2007, 56, 1685–1687.

- Ducreux, M.; Boutron, M.; Piard, F.; Carli, P.; Faivre, J. A 15-year series of gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: A population-based study. Br. J. Cancer 1998, 77, 511–514.

- Yoon, S.S.; Coit, D.G.; Portlock, C.S.; Karpeh, M.S. The Diminishing Role of Surgery in the Treatment of Gastric Lymphoma. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 28–37.

- Koch, P.; Del Valle, F.; Berdel, W.E.; Willich, N.A.; Reers, B.; Hiddemann, W.; Grothaus-Pinke, B.; Reinartz, G.; Brockmann, J.; Temmesfeld, A.; et al. Primary Gastrointestinal Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: II. Combined Surgical and Conservative or Conservative Management Only in Localized Gastric Lymphoma—Results of the Prospective German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 3874–3883.

- Burgers, J.; Taal, B.; Van Heerde, P.; Somers, R.; Jager, F.H.; Hart, A. Treatment results of primary stage I and II non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the stomach. Radiother. Oncol. 1988, 11, 319–325.

- Mittal, B.; Wasserman, T.H.; Griffith, R.C. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the stomach. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1983, 78, 780–787.

- Varsos, G.; Yahalom, J. Alternatives in the Management of Gastric Lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma 1991, 4, 1–8.

- Morton, J.; Leyland, M.; Hudson, G.V.; Anderson, L.; Bennett, M.; MacLennan, K.; Hudson, B.V. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: A review of 175 British National Lymphoma Investigation cases. Br. J. Cancer 1993, 67, 776–782.

- Ruskoné-Fourmestraux, A.; Aegerter, P.; Delmer, A.; Brousse, N.; Galian, A.; Rambaud, J.-C. Primary digestive tract lymphoma: A prospective multicentric study of 91 patients. Gastroenterology 1993, 105, 1662–1671.

- Amer, M.H.; El-Akkad, S. Gastrointestinal lymphoma in adults: Clinical features and management of 300 cases. Gastroenterology 1994, 106, 846–858.

- Sonnen, R.; Calavrezos, A.; Grimm, H.A.; Kuse, R. Kombinierte konservative Behandlung von lokalisierten Magenlymphomen. DMW-Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1994, 119, 863–868.

- Brincker, H.; D’Amore, F. A Retrospective Analysis of Treatment Outcome in 106 Cases of Localized Gastric Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas. Leuk. Lymphoma 1995, 18, 281–288.

- Liang, R.; Todd, D.; Chan, T.K.; Chiu, E.; Lie, A.; Kwong, Y.-L.; Choy, D.; Ho, F.C.S. Prognostic factors for primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. Hematol. Oncol. 1995, 13, 153–163.

- Koch, P.; Del Valle, F.; Berdel, W.E.; Willich, N.A.; Reers, B.; Hiddemann, W.; Grothaus-Pinke, B.; Reinartz, G.; Brockmann, J.; Temmesfeld, A.; et al. Primary Gastrointestinal Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: I. Anatomic and Histologic Distribution, Clinical Features, and Survival Data of 371 Patients Registered in the German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 3861–3873.

- Specht, L. The history of radiation therapy of lymphomas and description of early trials. In On-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas, 2nd ed.; Armitage, J.O., Coiffier, B., Dalla-Favera, R., Harris, N., Mauch, P.M., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 12–24.

- Zucca, E.; Bertoni, F.; Roggero, E.; Bosshard, G.; Cazzaniga, G.; Pedrinis, E.; Biondi, A.; Cavalli, F. Molecular Analysis of the Progression fromHelicobacter pylori–Associated Chronic Gastritis to Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid-Tissue Lymphoma of the Stomach. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 804–810.

- Yahalom, J.; Illidge, T.; Specht, L.; Hoppe, R.T.; Li, Y.-X.; Tsang, R.; Wirth, A. Modern Radiation Therapy for Extranodal Lymphomas: Field and Dose Guidelines from the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2015, 92, 11–31.

- Reinartz, G.; Pyra, R.P.; Lenz, G.; Liersch, R.; Stüben, G.; Micke, O.; Willborn, K.; Hess, C.F.; Probst, A.; Fietkau, R.; et al. Erfolgreiche Strahlenfeldverkleinerung bei gastralem Marginalzonenlymphom: Erfahrungen der Deutschen Studiengruppe Gastrointestinale Lymphome (DSGL). Strahlenther. Onkol. 2019, 195, 544–557.

- Teckie, S.; Qi, S.; Lovie, S.; Navarrett, S.; Hsu, M.; Noy, A.; Portlock, C.; Yahalom, J. Long-Term Outcomes and Patterns of Relapse of Early-Stage Extranodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma Treated with Radiation Therapy with Curative Intent. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2015, 92, 130–137.

- Yahalom, J.; Xu, A.J.; Noy, A.; Lobaugh, S.; Chelius, M.; Chau, K.; Portlock, C.; Hajj, C.; Imber, B.S.; Straus, D.J.; et al. Involved-site radiotherapy for Helicobacter pylori–independent gastric MALT lymphoma: 26 years of experience with 178 patients. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 1830–1836.

- Loehr, W.J.; Mujahed, Z.; Zahn, F.D.; Gray, G.F.; Thorbjarnarson, B. Primary Lymphoma of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Ann. Surg. 1969, 170, 232–238.

- Travis, L.B.; Curtis, R.E.; Glimelius, B.; Holowaty, E.; Leeuwen, F.E.V.; Lynch, C.F.; Adami, J.; Gospodarowicz, M.; Wacholder, S.; Inskip, P.; et al. Second Cancers Among Long-term Survivors of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 1932–1937.

- Travis, L.B.; Ng, A.K.; Allan, J.; Pui, C.-H.; Kennedy, A.R.; Xu, X.G.; Purdy, J.A.; Applegate, K.; Yahalom, J.; Constine, L.S.; et al. Second Malignant Neoplasms and Cardiovascular Disease Following Radiotherapy. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 357–370.

- Hoskin, P.J.; Kirkwood, A.A.; Popova, B.; Smith, P.; Robinson, M.; Gallop-Evans, E.; Coltart, S.; Illidge, T.; Madhavan, K.; Brammer, C.; et al. 4 Gy versus 24 Gy radiotherapy for patients with indolent lymphoma (FORT): A randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 457–463.

- Lowry, L.; Smith, P.; Qian, W.; Falk, S.; Benstead, K.; Illidge, T.; Linch, D.; Robinson, M.; Jack, A.; Hoskin, P. Reduced dose radiotherapy for local control in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A randomised phase III trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2011, 100, 86–92.

- Zelenetz, A.D.; Gordon, L.I.; Abramson, J.S.; Advani, R.H.; Bartlett, N.; Caimi, P.F.; Chang, J.E.; Chavez, J.C.; Christian, B.; Fayad, L.E.; et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: B-Cell Lymphomas, Version 3.2019. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 650–661.

- Reinartz, G.; Baehr, A.; Kittel, C.; Oertel, M.; Haverkamp, U.; Eich, H. Biophysical Analysis of Acute and Late Toxicity of Radiotherapy in Gastric Marginal Zone Lymphoma—Impact of Radiation Dose and Planning Target Volume. Cancers 2021, 13, 1390.

- Willich, N.A.; Reinartz, G.; Horst, E.J.; Delker, G.; Reers, B.; Hiddemann, W.; Tiemann, M.; Parwaresch, R.; Grothaus-Pinke, B.; Kocik, J.; et al. Operative and conservative management of primary gastric lymphoma: Interim results of a German multicenter study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2000, 46, 895–901.

- Maor, M.H.; Velasquez, W.S.; Fuller, L.M.; Silvermintz, K.B. Stomach conservation in stages IE and IIE gastric non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1990, 8, 266–271.

- Taal, B.G.; Burgers, J.M.; van Heerde, P.; Hart, A.A.; Somers, R. The clinical spectrum and treatment of primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the stomach. Ann. Oncol. 1993, 4, 839–846.

- Kocher, M.; Müller, R.-P.; Ross, D.; Hoederath, A.; Sack, H. Radiotherapy for treatment of localized gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Radiother. Oncol. 1997, 42, 37–41.

- Schechter, N.R.; Portlock, C.S.; Yahalom, J. Treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the stomach with radiation alone. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 1916–1921.

- Tsang, R.W.; Gospodarowicz, M.K. Management of localized (stage I and II) clinically aggressive lymphomas. Ann. Hematol. 2001, 80, B66–B72.

- Koch, P.; Probst, A.; Berdel, W.E.; Willich, N.A.; Reinartz, G.; Brockmann, J.; Liersch, R.; Del Valle, F.; Clasen, H.; Hirt, C.; et al. Treatment Results in Localized Primary Gastric Lymphoma: Data of Patients Registered within the German Multicenter Study (GIT NHL 02/96). J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 7050–7059.

- Della Biancia, C.; Hunt, M.; Furhang, E.; Wu, E.; Yahalom, J. Radiation treatment planning techniques for lymphoma of the stomach. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2005, 62, 745–751.

- Avilés, A.; Nambo, M.J.; Neri, N.; Talavera, A.; Cleto, S. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the stomach: Results of a controlled clinical trial. Med. Oncol. 2005, 22, 57–62.

- Watanabe, M.; Isobe, K.; Uno, T.; Harada, R.; Kobayashi, H.; Ueno, N.; Ito, H. Intrafractional gastric motion and interfractional stomach deformity using CT images. J. Radiat. Res. 2011, 52, 660–665.

- Vrieling, C.; de Jong, D.; Boot, H.; de Boer, J.P.; Wegman, F.; Aleman, B.M.P. Long-term results of stomach-conserving therapy in gastric MALT lymphoma. Radiother. Oncol. 2008, 87, 405–411.

- Tomita, N.; Kodaira, T.; Tachibana, H.; Nakamura, T.; Mizoguchi, N.; Takada, A. Favorable outcomes of radiotherapy for early-stage mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Radiother. Oncol. 2009, 90, 231–235.

- Ono, S.; Kato, M.; Takagi, K.; Kodaira, J.; Kubota, K.; Matsuno, Y.; Komatsu, Y.; Asaka, M. Long-term treatment of localized gastric marginal zone B-cell mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma including incidence of metachronous gastric cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 25, 804–809.

- Goda, J.S.; Gospodarowicz, M.; Pintilie, M.; Wells, W.; Hodgson, D.C.; Sun, A.; Crump, M.; Tsang, R.W. Long-term outcome in localized extranodal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas treated with radiotherapy. Cancer 2010, 116, 3815–3824.

- Fischbach, W.; Schramm, S.; Goebeler, E. Outcome and quality of life favour a conservative treatment of patients with primary gastric lymphoma. Z. Gastroenterol. 2011, 49, 430–435.

- Wirth, A.; Gospodarowicz, M.; Aleman, B.M.P.; Bressel, M.; Ng, A.; Chao, M.; Hoppe, R.T.; Thieblemont, C.; Tsang, R.; Moser, L.; et al. Long-term outcome for gastric marginal zone lymphoma treated with radiotherapy: A retrospective, multi-centre, International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group study. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 1344–1351.

- Abe, S.; Oda, I.; Inaba, K.; Suzuki, H.; Yoshinaga, S.; Nonaka, S.; Morota, M.; Murakami, N.; Itami, J.; Kobayashi, Y.; et al. A Retrospective Study of 5-year Outcomes of Radiotherapy for Gastric Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma Refractory to Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 43, 917–922.

- Ruskoné-Fourmestraux, A.; Matysiak-Budnik, T.; Fabiani, B.; Cervera, P.; Brixi, H.; Le Malicot, K.; Nion-Larmurier, I.; Fléjou, J.-F.; Hennequin, C.; Quéro, L. Exclusive moderate-dose radiotherapy in gastric marginal zone B-cell MALT lymphoma: Results of a prospective study with a long term follow-up. Radiother. Oncol. 2015, 117, 178–182.

- Ohkubo, Y.; Saito, Y.; Ushijima, H.; Onishi, M.; Kazumoto, T.; Saitoh, J.-I.; Kubota, N.; Kobayashi, H.; Maseki, N.; Nishimura, Y.; et al. Radiotherapy for localized gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: Long-term outcomes over 10 years. J. Radiat. Res. 2017, 58, 537–542.

- Pinnix, C.C.; Gunther, J.R.; Milgrom, S.A.; Cruz-Chamorro, R.; Medeiros, L.J.; Khoury, J.D.; Amini, B.; Neelapu, S.; Lee, H.J.; Westin, J.; et al. Outcomes After Reduced-Dose Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy for Gastric Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) Lymphoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 104, 447–455.

- Saifi, O.; Lester, S.C.; Rule, W.; Stish, B.J.; Stafford, S.; Pafundi, D.H.; Jiang, L.; Menke, D.; Moustafa, M.A.; Rosenthal, A.; et al. Comparable Efficacy of Reduced Dose Radiation Therapy for the Treatment of Early Stage Gastric Extranodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma of Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 6, 100714.

- Archer, V.W.; Cooper, G. Lymphosarcoma of the stomach, diagnosis and treatment. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1939, 42, 332–340.

- Musshoff, K.; Schmidt-Vollmer, H. Prognostic significance of primary site after radiotherapy in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomata. Br. J. Cancer Suppl. 1975, 2, 425–434.

- Rosenberg, S.A.; Dorfman, R.F.; Kaplan, H.S. A summary of the results of a review of 405 patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma at Stanford University. Br. J. Cancer Suppl. 1975, 2, 168–173.

- Sutcliffe, S.B.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Bush, R.S.; Brown, T.C.; Chua, T.; Bean, H.A.; Clark, R.M.; Dembo, A.; Fitzpatrick, P.J.; Peters, M.V. Role of radiation therapy in localized non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Radiother. Oncol. 1985, 4, 211–223.

- Reinartz, G.; Kardels, B.; Koch, P.; Willich, N. Analysis of Failures after Whole Abdominal Irradiation in Gastrointestinal Lympomas. Is Prophylactic Irradiation of Inguinal Lymph Nodes Required? German Multicenter Study Group on GI-NHL, University of Muenster. Strahlenther. Onkol. 1999, 175, 601–605.

- Shiu, M.H.; Karas, M.; Nisce, L.; Lee, B.J.; Filippa, D.A.; Lieberman, P.H. Management of Primary Gastric Lymphoma. Ann. Surg. 1982, 195, 196–202.

- Herrmann, R.; Panahon, A.M.; Barcos, M.P.; Walsh, D.; Stutzman, L. Gastrointestinal involvement in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer 1980, 46, 215–222.

- Bush, R.S.; Ash, C.L. Primary Lymphoma of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Radiology 1969, 92, 1349–1354.

- Hockey, M.S.; Powell, J.; Crocker, J.; Fielding, J.W.L. Primary gastric lymphoma. Br. J. Surg. 1987, 74, 483–487.

- Jones, R.E.; Willis, S.; Innes, D.J.; Wanebo, H.J. Primary gastric lymphoma: Problems in staging and management. Am. J. Surg. 1988, 155, 118–123.

- Contreary, K.; Nance, F.C.; Becker, W.F. Primary Lymphoma of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Ann. Surg. 1980, 191, 593–598.

- Rosen, C.B.; VAN Heerden, J.A.; Martin, J.K.; Wold, L.E.; Ilstrup, D.M. Is an Aggressive Surgical Approach to the Patient with Gastric Lymphoma Warranted? Ann. Surg. 1987, 205, 634–640.

- Shimm, D.S.; Dosoretz, D.E.; Anderson, T.; Linggood, R.M.; Harris, N.L.; Wang, C.C. Primary gastric lymphoma. An analysis with emphasis on prognostic factors and radiation therapy. Cancer 1983, 52, 2044–2048.

- Fischbach, W.; Dragosics, B.; Kolve–Goebeler, M.; Ohmann, C.; Greiner, A.; Yang, Q.; Böhm, S.; Verreet, P.; Horstmann, O.; Busch, M.; et al. Primary gastric B-Cell lymphoma: Results of a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology 2000, 119, 1191–1202.

- Lim, F.E.; Hartman, A.S.; Tan, E.G.C.; Cady, B.; Meissner, W.A. Factors in the prognosis of gastric lymphoma. Cancer 1977, 39, 1715–1720.

- Hoskin, P.; Popova, B.; Schofield, O.; Brammer, C.; Robinson, M.; Brunt, A.M.; Madhavan, K.; Illidge, T.; Gallop-Evans, E.; Syndikus, I.; et al. 4 Gy versus 24 Gy radiotherapy for follicular and marginal zone lymphoma (FoRT): Long-term follow-up of a multicentre, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 332–340.

- Tsang, R.W.; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Pintilie, M.; Wells, W.; Hodgson, D.C.; Sun, A.; Crump, M.; Patterson, B.J. Localized Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma Treated with Radiation Therapy Has Excellent Clinical Outcome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 4157–4164.

- Zelenetz, A.D.; Gordon, L.I.; Chang, J.E.; Christian, B.; Abramson, J.S.; Advani, R.H.; Bartlett, N.L.; Budde, L.E.; Caimi, P.F.; De Vos, S. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas. NCCN Guidelines Insights: B-Cell Lymphomas, Version 5.2021. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 1218–1230.

- Pinnix, C.C.; Dabaja, B.S.; Milgrom, S.A.; Smith, G.L.; Abou, Z.; Nastoupil, L.; Romaguera, J.; Turturro, F.; Fowler, N.; Fayad, L.; et al. Ultra-low-dose radiotherapy for definitive management of ocular adnexal B-cell lymphoma. Head Neck 2017, 39, 1095–1100.

More