Microalgae have been considered as one of the most promising biomass feedstocks for various industrial applications such as biofuels, animal/aquaculture feeds, food supplements, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceuticals. Several biotechnological challenges associated with algae cultivation, including the small size and negative surface charge of algal cells as well as the dilution of its cultures, need to be circumvented, which increases the cost and labor. Therefore, efficient biomass recovery or harvesting of diverse algal species represents a critical bottleneck for large-scale algal biorefinery process. Among different algae harvesting techniques (e.g., centrifugation, gravity sedimentation, screening, filtration, and air flotation), the flocculation-based processes have acquired much attention due to their promising efficiency and scalability.

- Microalgae

- harvesting

- flocculation

- biomass

- biofuel

- biorefienry

- Magnetic particle

- Electroflotation

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Microalgal biomass has attracted much attention in the academic and industrial fields due to its various industrial applications such as animal/aquaculture feeds, food supplements, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceuticals [1,2]. Recently, petroleum-fuel scarcity as well as global warming associated with greenhouse gas emissions (e.g., CO

Microalgal biomass has attracted much attention in the academic and industrial fields due to its various industrial applications such as animal/aquaculture feeds, food supplements, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceuticals [1][2]. Recently, petroleum-fuel scarcity as well as global warming associated with greenhouse gas emissions (e.g., CO

2) are obliging scientists and engineers to actively look for new and renewable sources of transportation fuels [3]. Various liquid and gaseous biofuels, such as diesel, aviation fuel, ethanol, butanol, hydrogen, and methane, can be produced from algal biomass through biological and thermochemical transformation technologies [4,5].

) are obliging scientists and engineers to actively look for new and renewable sources of transportation fuels [3]. Various liquid and gaseous biofuels, such as diesel, aviation fuel, ethanol, butanol, hydrogen, and methane, can be produced from algal biomass through biological and thermochemical transformation technologies [4][5].

Microalgae can utilize CO

2 as an inorganic carbon substrate using light energy and can be grown using diverse water resources, including freshwater, seawater, and even industrial/domestic wastewater. They can be also cultivated at a large-scale using different bioreactor systems such as open ponds and photobioreactors [6,7]. However, due to the low concentration (~5 g/L) in culture, small size (~5 μm) and negative surface charge (~−20 mV) of algal cells, external energy and/or chemicals are generally required to accelerate their recovery from base water [8,9].

as an inorganic carbon substrate using light energy and can be grown using diverse water resources, including freshwater, seawater, and even industrial/domestic wastewater. They can be also cultivated at a large-scale using different bioreactor systems such as open ponds and photobioreactors [6][7]. However, due to the low concentration (~5 g/L) in culture, small size (~5 μm) and negative surface charge (~−20 mV) of algal cells, external energy and/or chemicals are generally required to accelerate their recovery from base water [8][9]. Furthermore, other morphological and physiological characteristics of algal cells such as shape, cell wall structure, and extracellular organic matter (EOM) change significantly depending on the nutritional and environmental conditions including medium composition, light, temperature, pH, culture duration, and bioreactor type [10]. The algae harvesting costs are generally estimated at 20–30%, with the occasional rise to 60%, of the total biomass production cost, depending on the algal species and culture process used [11][12]. Therefore, the development of a high-efficiency and cost-effective harvesting process is key to achieving commercial scale algae-based process.

Algal biomass harvesting has been extensively studied with particular focus on centrifugation, gravity sedimentation, screening, filtration, air flotation, and flocculation techniques. However, there is no single universal harvesting method for all algal species and/or applications, which is both technically and economically viable [13][14]. For instance, centrifugation is based on a mechanical gravitational force that allows for efficient harvesting of suspended cells in a short time. However, due to the intensive energy requirement, it is recommended only for high-value algal products such as in foods and pharmaceuticals [14][15]. In the filtration process, micro-sized algal cells can be passed through a suitable membrane under high pressure to obtain a thick paste of algal biomass [16]. This size-exclusion method may be useful and scalable for algae harvesting only if problems in membrane blocking can be minimized or prevented [17][18]. The air flotation (or inverted sedimentation) harvesting process is based on the generation of up-rising gas bubbles that bind to algal cells and induce their flotation to the liquid surface [19]. However, due to differences in the surface hydrophobicity of algal cells, harvesting efficiency varies greatly depending on the species of algae [20]. It should also be noted that the high operation cost for producing small air bubbles can limit large-scale commercialization.

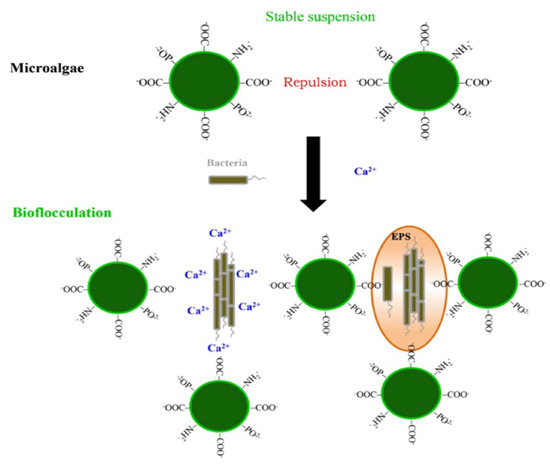

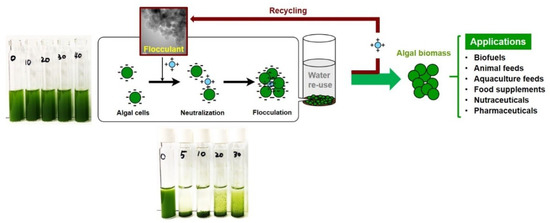

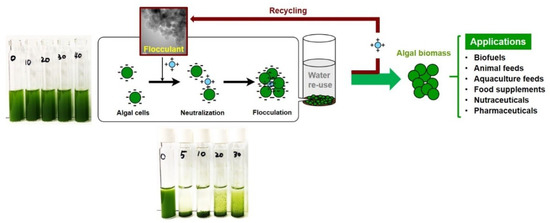

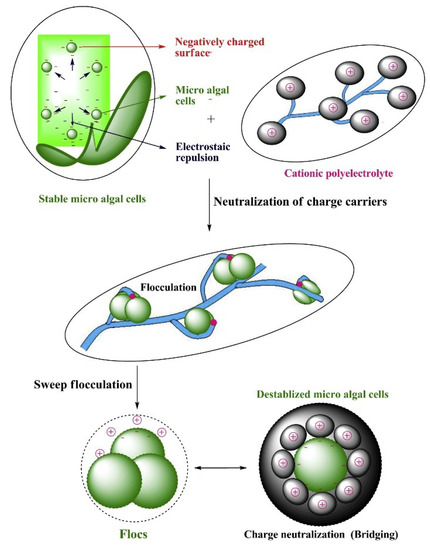

Flocculation refers to the aggregation of unstable and small particles through surface charge neutralization, electrostatic patching and/or bridging after addition of flocculants. Flocs formation allows for separation (or recovery) by simple gravity-induced settling or any other conventional separation method [21][22]. The flocculation process is simple and efficient, and has been extensively investigated as a promising strategy for harvesting various algal species [9][23]. Figure 1 shows the flocculation harvesting process of algal cells for algal biorefinery.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the flocculation harvesting process of algal cells with a recyclable flocculant.

As the flocculant plays a major role in the flocculation harvesting process, the discovery of a highly efficient and cost-effective flocculant has forever remained a challenge in most studies. Nowadays, the use of conventional inorganic metal salts such as aluminum sulfate and ferric sulfate has been reduced due to high dosage and biomass contamination [9]. Various natural and synthetic organic flocculants have been designed and developed to improve flocculation efficiency. However, the former have high production cost and a short shelf-life while the latter have adverse effects on harvested biomass and non-biodegradability, due to their petroleum origins [24]. Metal cations released from the electrode under direct electric current condition are able to electrostatically attract almost all types of algal cells, resulting in efficient flocculation. Significant efforts are being directed to prevent electrode/biomass fouling and to reduce systemic/electric cost for large-scale algae harvesting. Nanoparticles in either single or hybrid forms decorated with various cationic chemicals have been employed for rapid algae separation and/or multi-functionalities such as cell disruption and lipid extraction [25]. This approach although highly efficient, is expensive and is mostly limited to laboratory-scale studies. Spontaneous aggregation of algal cells under specific conditions and the use of a self-flocculating microorganism can be considered as sustainable and environment-friendly [22][26]. However, species-specific reactivity, availability of low-cost bio-flocculant-microorganisms, and process scale-up should be properly considered for practical applications. Ideally, in addition to excellent harvesting efficiency and promising scalability, the industrial flocculant should satisfy the demands for recyclability, low toxicity, low-cost material, and massive production process.

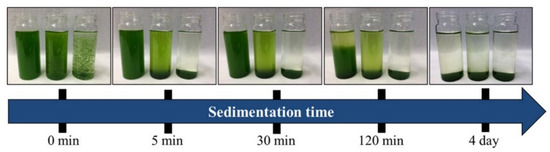

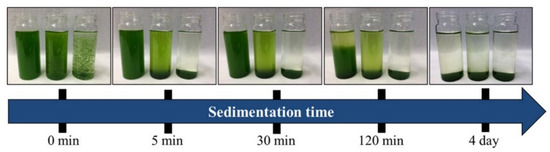

2. Auto-Flocculation

In auto-flocculation, suspended algal cells spontaneously aggregate, forming large flocs, which induce their simple gravitational sedimentation (Figure 2). This phenomenon has been observed in various algal species particularly under non-ideal culture conditions such as change in pH and cultural aging, as summarized in Table 1. Both alkaline and acidic conditions have been reported to reduce the intensities of the negative surface charge of algal cells, thereby promoting their self-aggregation [27]. Under alkaline conditions above pH 9, the changes in the surface charge of algal cells are mainly attributable to significant secretion of protective extracellular polymers [28]. Under acidic conditions, fluctuating dissociations of carboxyl and amine groups in the algal cell wall can cause changes in surface charge.

Furthermore, other morphological and physiological characteristics of algal cells such as shape, cell wall structure, and extracellular organic matter (EOM) change significantly depending on the nutritional and environmental conditions including medium composition, light, temperature, pH, culture duration, and bioreactor type [10]. The algae harvesting costs are generally estimated at gure 20–30%, with the occasional rise to 60%, of the total biomass production cost, depending on the algal species and culture process used [11,12]. Therefore, the development of a high-efficiency and cost-effective harvesting process is key to achieving commercial scale algae-based process.

Algal biomass harvesting has been extensively studied with particular focus on centrifugation, gravity sedimentation, screening, filtration, air flotation, and floto-flocculation techniques. However, there is no single universal hharvesting method for allof algal species and/or applications, which is both technically and economically viable [13,14]. For inbiomastance, centrifugation is based on a mechanical gravitational force that allows for efficient harvesting of suspended cells in a short time. However, due to the intensive energy requirement, it is recommended only for high-value algal products such as in foods and pharmaceuticals [14,15]. In the filtration pro. Three vials cess, micro-sized algal cells can be passed through a suitable membrane under high pressure to obtain a thick paste of algal biomass [16]. This size-exclusion method mntain algal say be useful and scalable for algae harvesting only if problems in membrane blocking can be minimized or prevented [17,18]. The air fplotation (or inverted sedimentation) harvesting process is based on the generation of up-rising gas bubbles that bind to algal cells and induce their flotation to the liquid surface [19]. However, due to ds cultured ifferences in the surface hydrophobicity of algal cells, harvesting efficiency varies greatly depending on the species of algae [20]. It should also be different noted that the high operation cost for producing small air bubbles can limit large-scale commercialization.

Flotrate concculatioen refers to the aggregation of unstable and small particles through surface charge neutralization, electrostatic patching and/or bridging after addition of flocculants. Flocs formation allows for separation (or recovery) by simple gravity-induced settling or any other conventional separation method [21,22]. The fltrations: (left) 0.5×; (middle) 1× (occulation process is simple and efficient, and has been extensively investigated as a promising strategy for harvesting various algal species [9,23]. Figure 1 shows the flocculiginal); ation harvesting process of algal cells for algal biorefinery.

As the flocculant plays a major role in the flocculation harvesting process, the discovery of a highly efficient and cost-effective flocculant has forever remained a challenge in most studies. Nowadays, the use of conventional inorganic metal salts such as aluminum sulfate and ferric sulfate has been reduced due to high dosage and biomass contamination [9](right) 2×. Various natural and synthRetic organic flocculants have been designed and developed to improve flocculation efficiency. However, the former have high production cost and a short shelf-life while the latter have adverse effects on harvested biomass and non-biodegradability, due to their petroleum origins [24]. Metal cations released printed from Refrom the electrode under direct electricrence current condition are able to electrostatically attract almost all types of algal cells[29], resulting in efficient flocculation. Significant efforts are being directed to prevent electrode/biomass fouling and to reduce systemic/electric cost for large-scale algae harvesting. Nanoparticles in either single or hybrid forms decorated with various cationic chemicals have been employed for rapid algae separation and/or multi-functionalities such as cell disruption and lipid extraction [25]. This approach alstributed under though highly efficient, is expensive and is mostly limited to laboratory-scale studies. Spontaneous aggregation of algal cells under specific conditions and the use of a self-flocculating microorganism can be considered as sustainable and environment-friendly [22,26]. However, species-specific reactivity, availability of low-cose terms of t bio-flocculant-microorganisms, and process scale-up should be properly considered for practical applications. Ideally, in addition to excellent harvesting efficiency and promising scalability, the industrial flocculant should satisfy the demands for recyclability, low toxicity, low-cost material, and massive production process.

2. Auto-Flocculation

In aue Creative Commons Atto-flocculation, suspended algal cells spontaneously aggregate, forming large flocs, which induce their simple gravitational sedimentation (Figure 2). This phenomenon has ibeen observed in various algal species particularly under non-ideal culture conditions such as change in pH and cultural aging, as summarized in Table 1tion License. Both alkaline and acidic conditions have been reported to reduce the intensities of the negative surface charge of algal cells, thereby promoting their self-aggregation [31]. Under alkaline conditions above pH 9, the changes in the surface charge of algal cells are mainly attributable to significant secretion of protective extracellular polymers [32]. Under acidic conditions, fluctuating dissociations of carboxyl and amine groups in the algal cell wall can cause changes in surface charge.

Table 1. Comparison of auto-flocculation techniques for algae harvesting.

|

Condition |

Alga (Cell Density) |

Optimal Harvesting |

Dosage |

Ref. |

|||||||||||||

Alga (Cell Density) | Optimal Harvesting | Ref. |

Acidic pH |

pH 4.0 |

C. ellipsoideum (4.38 g/L) |

95% @ 15 min |

|||||||||||

Aminoclay-based nanoparticle | [31][27] |

||||||||||||||||

Al-AC | 0.6 g/L | Chlorella sp. KR-1 (1.7 g/L) | 100% @ 30 min |

[99] |

[74] |

pH 4.0 |

C. nivale (4.17 g/L) |

94% @ 15 min |

[31][27] |

||||||||

|

pH 4.0 |

Scenedesmus sp. (6.94 g/L) |

98% @ 15 min |

[31][27] |

||||||||||||||

|

Alkaline pH |

pH 11.5 |

||||||||||||||||

45,46][36][37]. A bio-flocculant-microorganism can be prepared by co-culturing with target algae or culturing separately in a different bioreactor, before performing the intended use [22,30][22][38]. Although the mechanism of bio-flocculation has not been clearly elucidated, it is believed that it is mainly a function of the reactivity of the extracellular biopolymer and/or the direct adsorption of the self-flocculating microorganisms on the target algae [23,27][23][39].

Flocculant (Dosage) | Alga (Cell Density, Volume or Amount) | Optimal Harvesting | Ref. | ||||||||||||||||||

Fungus | A. fumigatus | C. protothecoides | ~90% @ 24 h |

[47] |

[40] |

||||||||||||||||

A. fumigatus (1.5–2.0 × 107 spores/L) |

Al2(SO4)3 (152 mg/L) | S. quadricauda (5–8 × 108 cell/mL) |

Chlorella sp. (0.12 g/L) | ~97% @ 48 h |

100% @ 60 min |

||||||||||||||||

AC-conjugated TiO2 | 3.0 g/L | Chlorella sp. KR-1 (1.5 g/L) |

[49] |

[41] |

|||||||||||||||||

[65] | [ |

A. fumigatus | T. suecica | ~90% @ 24 h |

[47] |

[40] |

|||||||||||||||

] | |||||||||||||||||||||

~85% @ 10 min | [100] |

Al2(SO |

A. lentulus (1.0 × 106 spores/mL) |

C. muelleri #862 (0.42 g/L) |

Chroococcus sp. (1.58 g/L) | ~100% @ 24 h |

100% @ 30 min |

[34][ |

[48]30] | ||||||||||||

[ | 42] |

pH 11.0 |

C. vulgaris (0.5 g/L) |

95% @ 60 min |

[35][31] |

||||||||||||||||

4)3 (180 mg/L) |

Scenedesmus sp. (0.20 g/L) |

90% @ 20 min |

[66][55] |

||||||||||||||||||

5.0 g/L | Chlorella sp. (1.3 g/L) | ~100% @ 30 min | |||||||||||||||||||

97% @ 40 min | |||||||||||||||||||||

[81] | |||||||||||||||||||||

[ | |||||||||||||||||||||

] | |||||||||||||||||||||

[ | ] | ||||||||||||||||||||

AC-induced humic acid |

[101] |

[76] |

Al2(SO4)3 (20 mg/L) |

C. reinhardtii (0.31 g/L) |

|||||||||||||||||

AC-templated nZVI | 19.1 g/L |

90% @ 20 min |

Chlorella sp. KR-1 (1.5 g/L) |

[66][55] |

|||||||||||||||||

~100% @ 3 min | [102] |

[77] |

Penicillium cells (1.92 g) |

Al2(SO4 | Chlorella sp. (3.84 g) | ) | ~98% @ 2.5 h | 3 |

[50] |

[43] |

pH 12.0 |

Chlorococcum sp. R-AP13 |

|||||||||

(438.1 μM) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

APTES-coated BaFe12O19 |

N. oculata (1.7 g/L) |

92% @ 320 min |

2.3 g/g cell |

[32][28] |

|||||||||||||||||

Chlorella sp. KR-1 | 99% @ 3 min |

[103] |

[78] |

Penicillium spores (1.1 × 104 cells/mL) | Chlorella sp. (3.84 g) |

94% @ 10 min |

Al2~99% @ 28 h |

[36][32] |

|||||||||||||

(SO4)3 (50 mg/L) |

S. limacinum (0.93 g/L) |

90% @ 20 min |

[50] |

[66][ | |||||||||||||||||

MgAC-Fe3O4 hybrid composites | 55] |

||||||||||||||||||||

4.7 g/L | Chlorella sp. KR-1 (1.75 g/L) | [43] |

99% @ 10 min |

[104] |

[79] |

pH 12.5 |

Ettlia sp. YC001 (1.2 g/L) |

||||||||||||||

Yeast |

CaO (60 mg/L) | Extracellular protein of S. bayanus (0.1 g/L) |

94% @ 30 min |

[37][ |

C. reinhardtii (10 mL)33] | ||||||||||||||||

MgAC-Fe3O4 hybrid composites |

C. vulgaris (1.5 g/L) |

85% @ 5min | 95% @ 3 h |

[67] |

4.3 g/L | [ |

S. obliquus (2.0 g/L) | 56] [51] |

[44 |

||||||||||||

99% @ 10 min | ] |

[104] |

[79] |

pH 10.4 |

N. oculate (2.27 × 105 cells/mL) |

90% @ 10 min |

[38] |

CaCO3-rich eggshell (80 mg/L) |

|||||||||||||

Mg-APTES |

C. vulgaris (2.3 g/L) |

99% @ 20 min | [34] |

||||||||||||||||||

Extracellular protein of S. bayanus (0.1 g/L) | Picochlorum sp. (10 mL) | 0.6 g/L | 75% @ 3 h |

[51] |

[44] |

[68][57] |

|||||||||||||||

Chlorella sp. KR-1 (1.7 g/L) | 100% @ 30 min |

[99] |

[74] | pH 11.6 |

S. quadricauda #507 (0.54 g/L) |

95% @ 30 min |

[34][30] |

||||||||||||||

S. bayanus (1:1, v/v) |

FeCl3 (0.4 g/L) | C. reinhardtii (10 mL) |

|||||||||||||||||||

Mg-APTES |

N. oculata (50 mL) | 80% @ 6 h |

94% @ 180 min | [51] |

1.0 g/L |

[ |

[69][ |

C. vulgaris (1.0 g/L) | 44] |

58] |

|||||||||||

97% @ 125 min | [98] |

[80] |

Culture aging |

16 days |

S. obliquus AS-6-1 (2.25 g/L) |

80% @ 30 min |

[39][35] |

||||||||||||||

3. Bio-Flocculation

Bio-flocculation is performed by adding a self-flocculating microorganism (or its extracellular biopolymer) to the culture broth to harvest non-flocculating, target algae (Figure 3). Bio-flocculants include bacteria, fungi, yeasts, or self-flocculating algae as well as their exudate-rich culture supernatants, as shown in Table 2. Since no chemical is required in this process similar to the case of auto-flocculation, the bio-flocculation method can also be considered as a sustainable and environmentally friendly technique for algal biomass harvesting [

S. bayanus (1:1, v/v) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Picochlorum sp. (10 mL) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

FeCl3 (143 mg/L) |

Chlorella sp. (0.12 g/L) | 60% @ 6 h |

[51] |

[ |

||||||||||||||||

Mg-AC and Ce-AC | 100% @ 40 min | 44] |

||||||||||||||||||

0.2 g/L |

[65][54] |

|||||||||||||||||||

Cyanobacteria | ~100% @ 60 min |

[105] |

[81] |

S. pastorianus (0.4 mg/g cell) | C. vulgaris (5 g/L) | 90% @ 70 min |

[45] |

FeCl3 (438.1 μM) |

[36] |

|||||||||||

composite | ||||||||||||||||||||

1.4 g/L | Chlorella sp. KR-1 (1.0 g/L) | ~99% @ 5 min |

[112] |

[88] |

||||||||||||||||

Chitosan-coated Fe3O4-TiO2 | 0.07 g/g cell | C. minutissima (3.0 g/L) | 98% @ 2 min |

[113] |

[89] |

6. Electrochemical Flocculation

6. Electrochemical Flocculation

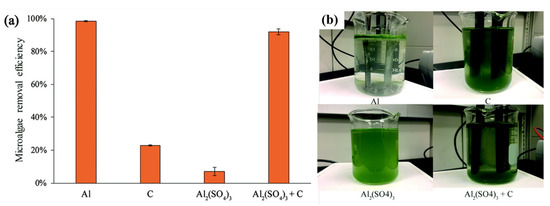

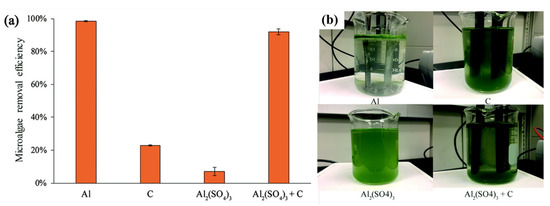

Electrochemical algae harvesting is generally carried out by passing a direct electrical current through electrodes into a culture broth wherein algal cells act as negatively charged colloids (Figure 5). There are two types of electrodes, “sacrificial electrodes”, whose metal ions are released into the aquatic environment, and “non-sacrificial electrodes” with non-reactive anodes and cathodes (Table 5). The electrical current in aqueous solution can cause a water-electrolysis reaction through either the sacrificial or non-sacrificial electrodes, which would release hydrogen and oxygen gases from the cathode and anode electrodes, respectively [90][91]. In this review, the electrochemical flocculation (ECF) process is discussed for the following three aspects: the sacrificial electrode, the non-sacrificial electrode, and electro-flotation.

Figure 5. Electrochemical aflocculgaeation harvesting is generally carried out by pasof microalgae using a direct electrical current throughluminum electrodes into a culture broth wherein algal cells act as negatively charged colloids (Figure 5). There are (Al), graphitwo types of electrodes, “sacrificial electrodes”, whose metal ions are released into the aquatic environment (C), aluminum sulfate (Al2(SO4)3), and “non-sgracrificialphite electrodes” with non-reactive anodes and cathodesaluminum sulfate (Table 5Al2(SO4).3 + TheC): electrical current in aqueous solution can cause a water-electrolysis reaction through either the sacrificial or non-sacrificial electrodes, which would release hydrogen and oxygen gases from the cathode and anode electrodes, respectively [124,125](a) microalgae removal efficiency; and (b) photographs of the harvesting processes. In this Repreview, the electrochemical flocculation (ECF) processinted from Reference is[92], disctribussed foted under the following three aspects: the sacrificial electrode, the non-sacrificial electrode, and electro-flotation.

Figure 5. Electrochemical flocculation harvesting of microalgae using aluminum electrodes (Al), graphite electrodes (C), aluminum sulfate (Al2(SO4)3), and graphite electrodes with aluminum sulfate (Al2(SO4)3 + C): (a) microalgae removal efficiency; and (b) photographs of the harvesting processes. Reprinted from Reference [128], distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Figure 5. Electrochemical flocculation harvesting of microalgae using aluminum electrodes (Al), graphite electrodes (C), aluminum sulfate (Al2(SO4)3), and graphite electrodes with aluminum sulfate (Al2(SO4)3 + C): (a) microalgae removal efficiency; and (b) photographs of the harvesting processes. Reprinted from Reference [128], distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Tablterms of the Creative 5. Comparison of sacrificial and non-sacrificial electrodes for algae harvestingmons Attribution License.

Table 5. Comparison of sacrificial and non-sacrificial electrodes for algae harvesting

|

Electrode |

Alga (Cell Density) |

Optimal Harvesting (Energy Requirement) |

Ref. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Sacrificial |

Al |

C. pyrenoidosa |

95.8% @ 1 min (0.3 kWh/kg cell) |

[126][93] |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Al |

C. vulgaris |

98% @ 4 min (0.3 kWh/kg cell) |

[129][94] |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Al |

M. aeruginosa (1.3 × 109 cells/mL) |

100% @ 45 min (0.4 kWh/m3) |

[130][95] |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Al |

Nannochloropsis sp. (2.5 g/L) |

97% @ 10 min (0.06 kWh/kg cell) |

[131][96] |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Al |

Scenedesmus sp. |

~98.5% @ 20 min (2.3 kWh/kg cell) |

[128][92] |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Al |

P. tricornutum |

80% @ 30 min (0.2 kWh/kg cell) |

[132][97] |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Fe |

C. vulgaris |

80% @ 30 min (2.1 kWh/kg cell) |

[132][97] |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Fe |

Chlorococcum sp. |

96% @ 15 min (9.2 kWh/kg cell) |

[133][98] |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Fe |

Green algae mixture (Scenedesmus, Kirchneriella, and Microcystis) |

~95.6% @ 24 h (4.4 kWh/kg cell) | Magnetic particle |

N. oculata (2.2 g/L) |

Fe3O4 nanoparticle |

78% @ 320 min |

55.9 mg cell/mg particles |

[32][28] |

||||||||||||||

B. braunii | 98% @ 1 min |

[106] |

[82] |

Bacterium |

Fe2(SO | Flavobacterium, Terrimonas, and Sphingobacterium | C. vulgaris (6 × 106 cells/mL) | 94% @ 24 h |

[52] |

[45] |

||||||||||||

Bio-flocculant secreted from S. silvestris W01 (3:1, w/w) | N. oceanica DUT01 | 90% @ 10 min |

[53] |

[46] |

||||||||||||||||||

Alga | S. obliquus AS-6–1 (1%, v/v) | S. obliquus FSP-3 (10 mL) | 83% @ 30 min |

[39] |

[35] |

|||||||||||||||||

Exudates-rich spent media of C. cf. pseudomicroporum (1:1, v/v) | S. ellipsoideus (15 mL) | 97% @ 4 h |

[54] |

[47] |

||||||||||||||||||

Phormidium sp. | Chlorella sp. | 100% @ 5 min |

[14] |

|||||||||||||||||||

4. Chemical Flocculation

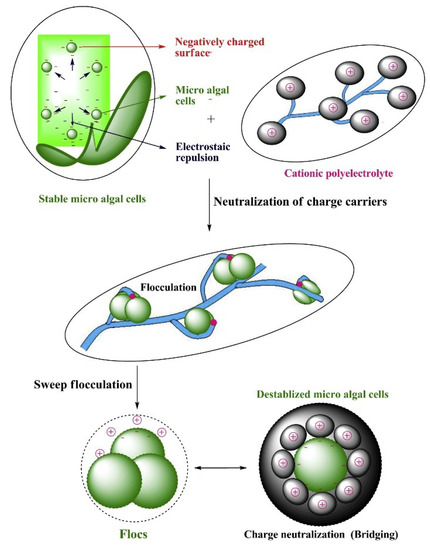

Chemical flocculation of algae occurs due to charge neutralization and electrostatic bridging between the suspended algal cells and the applied flocculant(s), resulting in floc formation and subsequent sedimentation (

Figure 4). M

). Multivalent inorganic chemicals, biopolymers, or inorganic–organic hybrid polymers have been extensively used as algae-harvesting flocculants. Aluminum sulfate and ferric chloride are of the most popular inorganic flocculants for wastewater clarification and algal biomass recovery [48]. Chitosan, cationic starches, modified tannins, and polyacrylamides are examples of organic polymers that are widely used [28][49]. The harvesting efficiency of both organic and inorganic flocculants depends largely on their physicochemical properties such as solubility and electronegativity, as well as the operating conditions, such as dosage and algal solution characteristics (e.g., cell density, pH, and ionic strength) [50][51]. It should be noted that the sizes of the flocs formed through charge neutralization with conventional inorganic chemicals are generally small, requiring high dosage for algae flocculation. On the other hand, the bridging and sweeping reactions between polymeric flocculants and algal cells can lead to the formation of larger sized flocs, thereby promoting efficient biomass recovery at a relatively low dosage [24]. Table 3 briefly compares the different inorganic and organic chemical flocculants for algae harvesting.

Figultivalrent inorganic chemicals, biopolymers, or inorganic–organic hybrid polymers have been extensively used as algae-harvesting flocculants. Aluminum sulfate and ferric chloride are of the most popular inorganic 4. A schematic diagram of chemical flocculants for wastewater clarification and algal biomass recovery [60]. Chitotion harvesan, cationic starches, modified tannins, and polyacrylamides are examples of organic polymers that are widely used [32,61]. The harvestng of microalgae using efficiency of both organic and inorganic flocculants depends largely on their physicochemical properties such as solubility and cationic polyelectronegativity, as well as the operating conditions, such as dosage and algal solution characteristics (e.g., celllyte. Reprinted from Reference density[52], pH, and ionic strength) [62,63]. It shoistribuld be noted that the sizes of the flocs formed through charge neutralization with conventional inorganic chemicals are generally small, requiring high dosage for algae flocculation. On the other hand, the bridging and sweeping reactions between polymeric flocculants and algal cells can lead to the formation of larger sized flocs, thereby promoting efficient biomass recovery at a relatively low dosage [24]. Table 3 under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribriefly compares uthe different inorganic and organic chemical flocculants for algae harvestingion License.

Table 3. Comparison of inorganic and organic chemical flocculants for algae harvesting.

Figure 4. A schematic diagram of chemical flocculation harvesting of microalgae using a cationic polyelectrolyte. Reprinted from Reference [29], distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Table 3. Comparison of inorganic and organic chemical flocculants for algae harvesting.

Figure 4. A schematic diagram of chemical flocculation harvesting of microalgae using a cationic polyelectrolyte. Reprinted from Reference [29], distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

Table 3. Comparison of inorganic and organic chemical flocculants for algae harvesting.

|

Flocculant (Dosage) |

Alga (Cell Density or Volume) |

Optimal Harvesting |

Ref. |

|||||||||||||

|

Inorganic flocculant |

Al2(SO4)3 (1.2 g/L) |

Tetraselmis sp. KCTC12236BP (3 g/L) |

86% @ 30 min |

[64][53] |

||||||||||||

[134] | ||||||||||||||||

[ | ||||||||||||||||

] | ||||||||||||||||

|

Fe |

Tetraselmis sp. |

94% @ 15 min (4.4 kWh/kg cell) |

[133][98] |

|||||||||||||

|

Non-sacrificial |

C |

C. sorokiniana |

~95% @ 15 min (1.6 kWh/kg cell) |

[124][90 | ||||||||||||

4)3 (0.6 g/L) |

N. oculata (50 mL) |

|||||||||||||||

] | Fe3O4 nanoparticle | |||||||||||||||

|

C | 5.8 mg cell/mg particles |

C. pyrenoidosa |

87% @ 180 min |

C. ellipsoidea |

79.2% @ 1 min (0.3 kWh/kg cell) |

[69][58] |

||||||||||

98% @ 1 min | [106] |

[82] |

Fe2(SO4)3 (1.0 g/L) |

|||||||||||||

[126] | [ |

Fe3O4 nanoparticle |

Chlorella sp. KR-1 (1.52 g/L) |

0.12 g/L |

98% @ 30 min |

N. maritima |

[70][59] |

|||||||||

95% @ 4 min | [107] |

[83] |

|

Mg(OH)2 | ||||||||||||

Fe3O4 magnetic particle | (1 mM) |

10 g/g cell |

Chlorella sp. (0.1 g/L) |

Chlorella sp. KR-1 |

90% @ 30 min |

99% @ 1 min |

[71][60] |

|||||||||

[108] | [84] |

Organic flocculant |

||||||||||||||

Fe3O4-embedded carbon microparticle |

Cationic inulin (60 mg/L) |

~25 g/L |

Botryococcus sp. |

Chlorella sp. KR-1 (~2 g/L) |

89% @ 15 min |

99% @ 1 min | [72][61] |

|||||||||

[109] | [85] |

Cationic starches (0.01 g/L) |

||||||||||||||

Fe3O4–PEI nanocomposite |

S. dimorphus (0.12 g/L) |

95% @ 90 min |

0.02 g/L |

[73][62] |

||||||||||||

C. ellipsoidea (0.75 g/L) | 97% @ 2 min |

[110] |

[86] |

Cationic starches (1.4:1, w/w) |

||||||||||||

PEI-coated Fe3O4 |

S. obliquus |

0.2 g/L |

90% @ 60 min |

S. dimorphus (1.8 g/L) |

[74][63] |

|||||||||||

82.7% @ 3 min |

[111] |

[87] |

Cationic starches (119 mg/g cell) |

B. braunii (0.62 g/L) |

94% @ 20 min |

|||||||||||

Fe3O4-carbon-microparticle |

[75][64] |

|||||||||||||||

10 g/L | Chlorella sp. KR-1 (2.0 g/L) | 99% @ 1 min |

[109] |

[85] |

Cationic starches (50 mg/L) |

|||||||||||

Chitosan–Fe3 |

S. limacinum (0.93 g/L) |

O |

90% @ 20 min |

4 |

[66][55] |

|||||||||||

] |

Cationic starches (7.1 mg/L) |

C. vulgaris (0.75 g/L) |

90% @ 120 min |

[76][65] |

||||||||||||

|

Cationic starches (89 mg/g cell) |

C. pyrenoidosa (1.02 g/L) |

96% @ 20 min |

[75][64] |

|||||||||||||

|

Chitosan (10 mg/g cell) |

C. sorokiniana |

99% @ 45 min |

[77][66] |

|||||||||||||

|

Chitosan (120 mg/L)) |

C. vulgaris (1 g/L) |

99% @ 3 min |

[78][67] |

|||||||||||||

|

Chitosan (40 mg/L) |

Scenedesmus sp. A1 |

82% @ 60 min |

[12] |

|||||||||||||

|

Chitosan (30 mg/L) |

Chlorella sp. (3 × 107 cells/mL) |

97% @ 60 min |

[61][49] |

|||||||||||||

|

Chitosan (30 mg/L) + sodium alginate (40 mg/L) |

S. obliquus |

86% @ 60 min |

[40][68] |

|||||||||||||

|

Epichlorohydrin-n,n- diisopropylamine-dimethylamine (8 mg/L) |

Scenedesmus sp. (100 mL) |

>90% @ 30 min |

[79][69] |

|||||||||||||

|

Modified tannin (10 mg/L) |

M. aeruginosa (1 × 109 cells/L) |

97% @ 120 min |

[80][70] |

|||||||||||||

|

Modified tannin (210 mg/L) |

Scenedesmus sp. |

Modified tannin (10 mg/L) |

N. oculate (400 mg/L) |

98% @ 30 min |

[82][72] |

|||||||||||

|

Poly-L-lysine (70–150 kDa, 0.5 mg/L) |

C. ellipsoidea (1 g/L) |

98% @ 75 min |

[83][73] |

|||||||||||||

5. Particle-Based Flocculation

Particle-based flocculation can potentially circumvent some drawbacks of conventional chemical flocculation such as bio-toxicity and difficulties related to chemical recovery. For these purposes, particle-based flocculants should be designed to be more efficient, recoverable, and/or have multi-functionalities other than algae recovery, such as cell disruption and lipid extraction [9]. Therefore, numerous research efforts have devoted effort towards the development of new and optimal nano/micro-particle-based flocculants. This section summarizes the recent progress in algae harvesting using the nano/micro-particle-based flocculants, namely aminoclay (AC)-based particles, magnetic particles (

), and more advanced multi-functional or recyclable particles.

Table 4. Comparison of particle-based flocculants for algae harvesting.

Kind | Flocculant |

7. Conclusion

The importance of microalgae research is increasing in parallel with increasing demands for food, animal feeds, pharmaceuticals, and biofuels. However, moving from lab-scale to commercial-scale applications still requires extensive developments for reliable, cheap, and eco-friendly algae cultivation and harvesting processes. The specific flocculation process should be carefully selected and optimized comprehensively in consideration of various key factors such as efficiency, environmental impact, operating cost, value-added utilization of whole biomass, characteristics of algal species, and culture conditions.

References

- Chen, M.F.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Di He, M.; Li, C.Y.; Zhou, C.X.; Hong, P.Z.; Qian, Z.J. Antioxidant peptide purified from enzymatic hydrolysates of Isochrysis Zhanjiangensis and its protective effect against ethanol induced oxidative stress of HepG2 cells. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2019, 24, 308–317.

- Eida, M.F.; Matter, I.A.; Darwesh, O.M. Cultivation of oleaginous microalgae Scenedesmus obliquus on secondary treated municipal wastewater as growth medium for biodiesel production. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 19, 38–50.

- Oh, Y.-K.; Hwang, K.-R.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.R.; Lee, J.-S. Recent developments and key barriers to advanced biofuels: A short review. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 257, 320–333.

- Enamala, M.K.; Enamala, S.; Chavali, M.; Donepudi, J.; Yadavalli, R.; Kolapalli, B.; Aradhyula, T.V.; Velpuri, J.; Kuppam, C. Production of biofuels from microalgae-a review on cultivation, harvesting, lipid extraction, and numerous applications of microalgae. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 49–68.

- El-Baz, F.K.; Gad, M.S.; Abdo, S.M.; Abed, K.A.; Matter, I.A. Performance and exhaust emissions of a diesel engine burning algal biodiesel blends. Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2016, 16, 151–158.

- Choi, Y.Y.; Hong, M.E.; Chang, W.S.; Sim, S.J. Autotrophic biodiesel production from the thermotolerant microalga Chlorella sorokiniana by enhancing the carbon availability with temperature adjustment. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2019, 24, 223–231.

- Kim, B.; Praveenkumar, R.; Choi, E.; Lee, K.; Jeon, S.G.; Oh, Y.-K. Prospecting for oleaginous and robust Chlorella spp. for coal-fired flue-gas-mediated biodiesel production. Energies 2018, 11, 2026.

- Branyikova, I.; Filipenska, M.; Urbanova, K.; Ruzicka, M.C.; Pivokonsky, M.; Branyik, T. Physicochemical approach to alkaline flocculation of Chlorella vulgaris induced by calcium phosphate precipitates. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 166, 54–60.

- Lee, Y.-C.; Lee, K.; Oh, Y.-K. Recent nanoparticle engineering advances in microalgal cultivation and harvesting processes of biodiesel production: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 184, 63–72.

- Darwesh, O.M.; Matter, I.A.; Eida, M.F.; Moawad, H.; Oh, Y.K. Influence of nitrogen source and growth phase on extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using cultural filtrates of Scenedesmus obliquus. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1465.

- Udom, I.; Zaribaf, B.H.; Halfhide, T.; Gillie, B.; Dalrymple, O.; Zhang, Q.; Ergas, S.J. Harvesting microalgae grown on wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 139, 101–106.

- Matter, I.A.; Darwesh, O.M.; El-baz, F.K. Using the natural polymer chitosan in harvesting Scenedesmus species under different concentrations and cultural pH values. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2016, 7, 254–260.

- Rashid, N.; Park, W.K.; Selvaratnam, T. Binary culture of microalgae as an integrated approach for enhanced biomass and metabolites productivity, wastewater treatment, and bioflocculation. Chemosphere 2018, 194, 67–75.

- Tiron, O.; Bumbac, C.; Manea, E.; Stefanescu, M.; Lazar, M.N. Overcoming microalgae harvesting barrier by activated algae granules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4646–4656.

- Gupta, P.L.; Lee, S.M.; Choi, H.J. Integration of microalgal cultivation system for wastewater remediation and sustainable biomass production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 139–149.

- Son, J., Sung, M., Ryu, H., Oh, Y.-K., Han, J.-I. Microalgae dewatering based on forward osmosis employing proton exchange membrane. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 57–62.

- Hwang, T.; Park, S.J.; Oh, Y.-K.; Rashid, N.; Han, J.I. Harvesting of Chlorella sp. KR-1 using a cross-flow membrane filtration system equipped with an anti-fouling membrane. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 139, 379–382.

- Kang, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J. Optimization of cross flow filtration system for Dunaliella tertiolecta and Tetraselmis sp. microalgae harvest. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 32, 1377–1380.

- Laamanen, C.A.; Ross, G.M.; Scott, J.A. Flotation harvesting of microalgae. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2016, 58, 75–86.

- Garg, S.; Wang, L.; Schenk, P.M. Effective harvesting of low surface-hydrophobicity microalgae by froth flotation. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 159, 437–441.

- Pahl, S.L.; Lee, A.K.; Kalaitzidis, T.; Ashman, P.J.; Sathe, S.; Lewis, D.M. Harvesting, thickening and dewatering microalgae biomass. In Algae for Biofuels and Energy; Borowwitzka, M.A., Moheimani, N.R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 5, pp. 165–185, ISBN 978-94-007-5478-2.

- Vandamme, D.; Foubert, I.; Muylaert, K. Flocculation as a low-cost method for harvesting microalgae for bulk biomass production. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 233–239.

- Wan, C.; Alam, M.A.; Zhao, X.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Guo, S.L.; Ho, S.H.; Chang, J.S.; Bai, F.W. Current progress and future prospect of microalgal biomass harvest using various flocculation technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 184, 251–257.

- Lee, C.S.; Robinson, J.; Chong, M.F. A review on application of flocculants in wastewater treatment. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2014, 92, 489–508.

- Nguyen, M.K.; Moon, J.-Y.; Bui, V.K.H.; Oh, Y.-K.; Lee, Y.-C. Recent advanced applications of nanomaterials in microalgae biorefinery. Algal Res. 2019, 41, 101522.

- Gultom, S.O.; Hu, B. Review of microalgae harvesting via co-pelletization with filamentous fungus. Energies 2013, 6, 5921–5939.

- Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A.; Li, T.; Sang, M.; Zhang, C. Freshwater microalgae harvested via flocculation induced by pH decrease. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 98.

- Shen, Y.; Cui, Y.; Yuan, W. Flocculation optimization of microalga Nannochloropsis oculata. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 169, 2049–2063.

- Nguyen, T.T.; Uemura, Y.; Krishnan, V.; Khalid, N.A. Autoflocculation of Scenedesmus quadricauda: Effects of aeration rate, aeration gas CO2 concentration and medium nitrogen concentration. Int. J. Biomass Renew. 2017, 6, 11–17.

- Huo, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Cui, F.; Zou, B.; You, W.; Yuan, Z.; Dong, R. Optimization of alkaline flocculation for harvesting of Scenedesmus quadricauda #507 and Chaetoceros muelleri #862. Energies 2014, 7, 6186–6195.

- Vandamme, D.; Foubert, I.; Fraeye, I.; Meesschaert, B.; Muylaert, K. Flocculation of Chlorella vulgaris induced by high pH: Role of magnesium and calcium and practical implications. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 105, 114–119.

- Ummalyma, S.B.; Mathew, A.K.; Pandey, A.; Sukumaran, R.K. Harvesting of microalgal biomass: Efficient method for flocculation through pH modulation. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 213, 216–221.

- Yoo, C.; La, H.J.; Kim, S.C.; Oh, H.M. Simple processes for optimized growth and harvest of Ettlia sp. by pH control using CO2 and light irradiation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2015, 112, 288–296.

- Tran, N.A.T.; Seymour, J.R.; Siboni, N.; Evenhuis, C.R.; Tamburic, B. Photosynthetic carbon uptake induces autoflocculation of the marine microalga Nannochloropsis oculata. Algal Res. 2017, 26, 302–311.

- Guo, S.L.; Zhao, X.Q.; Wan, C.; Huang, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.L.; Alam, M.A.; Ho, S.H.; Bai, F.W.; Chang, J.S. Characterization of flocculating agent from the self-flocculating microalga Scenedesmus obliquus AS-6-1 for efficient biomass harvest. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 145, 285–289.

- Prochazkova, G.; Kastanek, P.; Branyik, T. Harvesting freshwater Chlorella vulgaris with flocculant derived from spent brewer’s yeast. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 177, 28–33.

- Salim, S.; Kosterink, N.R.; Wacka, N.T.; Vermuë, M.H.; Wijffels, R.H. Mechanism behind autoflocculation of unicellular green microalgae Ettlia texensis. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 174, 34–38.

- Ummalyma, S.B.; Gnansounou, E.; Sukumaran, R.K.; Sindhu, R.; Pandey, A.; Sahoo, D. Bioflocculation: An alternative strategy for harvesting of microalgae—An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 242, 227–235.

- Alam, M.A.; Vandamme, D.; Chun, W.; Zhao, X.; Foubert, I.; Wang, Z.; Muylaert, K.; Yuan, Z. Bioflocculation as an innovative harvesting strategy for microalgae. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 15, 573–583.

- Muradov, N.; Taha, M.; Miranda, A.F.; Wrede, D.; Kadali, K.; Gujar, A.; Stevenson, T.; Ball, A.S.; Mouradov, A. Fungal-assisted algal flocculation: Application in wastewater treatment and biofuel production. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2015, 8, 24.

- Wrede, D.; Taha, M.; Miranda, A.F.; Kadali, K.; Stevenson, T.; Ball, A.S.; Mouradov, A. Co-cultivation of fungal and microalgal cells as an efficient system for harvesting microalgal cells, lipid production and wastewater treatment. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113497.

- Prajapati, S.K.; Kumar, P.; Malik, A.; Choudhary, P. Exploring pellet forming filamentous fungi as tool for harvesting non-flocculating unicellular microalgae. Bioenergy Res. 2014, 7, 1430–1440.

- Chen, J.; Leng, L.; Ye, C.; Lu, Q.; Addy, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, P.; Ruan, R.; Zhou, W. A comparative study between fungal pellet-and spore-assisted microalgae harvesting methods for algae bioflocculation. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 259, 181–190.

- Díaz-Santos, E.; Vila, M.; de la Vega, M.; León, R.; Vigara, J. Study of bioflocculation induced by Saccharomyces bayanus var. uvarum and flocculating protein factors in microalgae. Algal Res. 2015, 8, 23–29.

- Lee, J.; Cho, D.H.; Ramanan, R.; Kim, B.H.; Oh, H.M.; Kim, H.S. Microalgae-associated bacteria play a key role in the flocculation of Chlorella vulgaris. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 195–201.

- Wan, C.; Zhao, X.Q.; Guo, S.L.; Alam, M.A.; Bai, F.W. Bioflocculant production from Solibacillus silvestris W01 and its application in cost-effective harvest of marine microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica by flocculation. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 135, 207–212.

- Úbeda, B.; Gálvez, J.Á.; Michel, M.; Bartual, A. Microalgae cultivation in urban wastewater: Coelastrum cf. Pseudomicroporum as a novel carotenoid source and a potential microalgae harvesting tool. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 228, 210–217.

- Yaser, A.Z.; Cassey, T.L.; Hairul, M.A.; Shazwan, A.S. Current review on the coagulation/flocculation of lignin containing wastewater. Int. J. Waste Res. 2014, 4, 153–159.

- Toh, P.Y.; Azenan, N.F.; Wong, L.; Ng, Y.S.; Chng, L.M.; Lim, J.; Chan, D.J.C. The role of cationic coagulant-to-cell interaction in dictating the flocculation-aided sedimentation of freshwater microalgae. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2017, 43, 1–9.

- Kim, D.G.; Oh, H.M.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, H.G.; Ahn, C.Y. Optimization of flocculation conditions for Botryococcus braunii using response surface methodology. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 875–882.

- Singh, G.; Patidar, S.K. Microalgae harvesting techniques: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 217, 499–508.

- Pugazhendhi, A.; Shobana, S.; Bakonyi, P.; Nemestóthy, N.; Xia, A.; Kumar, G. A review on chemical mechanism of microalgae flocculation via polymers. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 21, e00302.

- Kwon, H.; Lu, M.; Lee, E.Y.; Lee, J. Harvesting of microalgae using flocculation combined with dissolved air flotation. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2014, 19, 143–149.

- Sanyano, N.; Chetpattananondh, P.; Chongkhong, S. Coagulation–flocculation of marine Chlorella sp. for biodiesel production. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 147, 471–476.

- Gerde, J.A.; Yao, L.; Lio, J.; Wen, Z.; Wang, T. Microalgae flocculation: Impact of flocculant type, algae species and cell concentration. Algal Res. 2014, 3, 30–35.

- Ma, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, P.; Ruan, R. Enhanced harvesting of Chlorella vulgaris using combined flocculants. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 180, 791–804.

- Choi, H.J. Effect of eggshells for the harvesting of microalgae species. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015, 29, 666–672.

- Surendhiran, D.; Vijay, M. Study on flocculation efficiency for harvesting Nannochloropsis oculata for biodiesel production. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2013, 5, 1761–1769.

- Kim, D.Y.; Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.H.; Han, J.I.; Park, J.Y.; Oh, Y.-K. Acidified-flocculation process for harvesting of microalgae: Coagulant reutilization and metal-free-microalgae recovery. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 239, 190–196.

- Vandamme, D.; Beuckels, A.; Markou, G.; Foubert, I.; Muylaert, K. Reversible flocculation of microalgae using magnesium hydroxide. Bioenergy Res. 2015, 8, 716–725.

- Rahul, R.; Kumar, S.; Jha, U.; Sen, G. Cationic inulin: A plant based natural biopolymer for algal biomass harvesting. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 72, 868–874.

- Hansel, P.A.; Riefler, R.G.; Stuart, B.J. Efficient flocculation of microalgae for biomass production using cationic starch. Algal Res. 2014, 5, 133–139.

- Anthony, R.; Sims, R. Cationic starch for microalgae and total phosphorus removal from wastewater. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. Symp. 2013, 130, 2572–2578.

- Peng, C.; Li, S.; Zheng, J.; Huang, S.; Li, D. Harvesting microalgae with different sources of starch-based cationic flocculants. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 181, 112–124.

- Tork, M.B.; Khalilzadeh, R.; Kouchakzadeh, H. Efficient harvesting of marine Chlorella vulgaris microalgae utilizing cationic starch nanoparticles by response surface methodology. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 583–588.

- Xu, Y.; Purton, S.; Baganz, F. Chitosan flocculation to aid the harvesting of the microalga Chlorella sorokiniana. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 129, 296–301.

- Rashid, N.; Rehman, S.U.; Han, J.I. Rapid harvesting of freshwater microalgae using chitosan. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 1107–1110.

- Matter, I.A.; Darwesh, O.M.; Eida, M.F. Harvesting of microalgae Scenedesmus obliquus using chitosan-alginate dual flocculation system. Biosci. Res. 2018, 15, 540–548.

- Gupta, S.K.; Kumar, M.; Guldhe, A.; Ansari, F.A.; Rawat, I.; Kanney, K.; Bux, F. Design and development of polyamine polymer for harvesting microalgae for biofuels production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 85, 537–544.

- Wang, L.; Liang, W.; Yu, J.; Liang, Z.; Ruan, L.; Zhang, Y. Flocculation of Microcystis aeruginosa using modified larch tannin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 5771–5777.

- Selesu, N.F.; de Oliveira, V.T.; Corrêa, D.O.; Miyawaki, B.; Mariano, A.B.; Vargas, J.V.; Vieira, R.B. Maximum microalgae biomass harvesting via flocculation in large scale photobioreactor cultivation. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 94, 304–309.

- Roselet, F.; Burkert, J.; Abreu, P.C. Flocculation of nannochloropsis oculata using a tannin-based polymer: Bench scale optimization and pilot scale reproducibility. Biomass Bioenerg. 2016, 87, 55–60.

- Noh, W.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.J.; Ryu, B.G.; Kang, C.M. Harvesting and contamination control of microalgae Chlorella ellipsoidea using the bio-polymeric flocculant α-poly-l-lysine. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 206–211.

- Lee, Y.C.; Kim, B.; Farooq, W.; Chung, J.; Han, J.I.; Shin, H.J.; Jeong, S.H.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Oh, Y.-K. Harvesting of oleaginous Chlorella sp. by organoclays. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 132, 440–445.

- Lee, Y.C.; Lee, H.U.; Lee, K.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, M.H.; Farooq, W.; Choi, J.S.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Oh, Y.-K.; Huh, Y.S. Aminoclay-conjugated TiO2 synthesis for simultaneous harvesting and wet-disruption of oleaginous Chlorella sp. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 245, 143–149.

- Lee, Y.C.; Oh, S.Y.; Lee, H.U.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, M.H.; Lee, G.W.; Park, J.Y.; Oh, Y.-K.; Ryu, T.; Han, Y.-K.; Chung, K.-S.; Huh, Y.S. Aminoclay-induced humic acid flocculation for efficient harvesting of oleaginous Chlorella sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 153, 365–369.

- Lee, Y.C.; Lee, K.; Hwang, Y.; Andersen, H.R.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, M.H.; Park, J.Y.; Han, Y.K.; Oh, Y.-K.; Huh, Y.S. Aminoclay-templated nanoscale zero-valent iron (nZVI) synthesis for efficient harvesting of oleaginous microalga, Chlorella sp. KR-1. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 4122–4127.

- Seo, J.Y.; Lee, K.; Lee, S.Y.; Jeon, S.G.; Na, J.G.; Oh, Y.-K.; Park, S.B. Effect of barium ferrite particle size on detachment efficiency in magnetophoretic harvesting of oleaginous Chlorella sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 152, 562–566.

- Kim, B.; Bui, V.K.H.; Farooq, W.; Jeon, S.G.; Oh, Y.-K.; Lee, Y.C. Magnesium aminoclay-Fe3O4 (MgAC-Fe3O4) hybrid composites for harvesting of mixed microalgae. Energies 2018, 11, 1359.

- Farooq, W.; Lee, Y.C.; Han, J.I.; Darpito, C.H.; Choi, M.; Yang, J.W. Efficient microalgae harvesting by organo-building blocks of nanoclays. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 749–755.

- Ji, H.M.; Lee, H.U.; Kim, E.J.; Seo, S.; Kim, B.; Lee, G.W.; Oh, Y.-K.; Kim, J.Y.; Huh, Y.S.; Song, H.A.; Lee, Y.C. Efficient harvesting of wet blue-green microalgal biomass by two-aminoclay [AC]-mixture systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 15, 313–318.

- Xu, L.; Guo, C.; Wang, F.; Zheng, S.; Liu, C.Z. A simple and rapid harvesting method for microalgae by in situ magnetic separation. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 10047–10051.

- Hu, Y.R.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.K.; Liu, C.Z.; Guo, C. Efficient harvesting of marine microalgae Nannochloropsis maritima using magnetic nanoparticles. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 138, 387–390.

- Lee, K.; Lee, S.Y.; Praveenkumar, R.; Kim, B.; Seo, J.Y.; Jeon, S.G.; Na, J.G.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, D.M.; Oh, Y.-K. Repeated use of stable magnetic flocculant for efficient harvest of oleaginous Chlorella sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 167, 284–290.

- Seo, J.Y.; Lee, K.; Praveenkumar, R.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.Y.; Oh, Y.-K.; Park, S.B. Tri-functionality of Fe3O4-embedded carbon microparticles in microalgae harvesting. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 2015, 206–214.

- Hu, Y.R.; Guo, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.K.; Pan, F.; Liu, C.Z. Improvement of microalgae harvesting by magnetic nanocomposites coated with polyethylenimine. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 242, 341–347.

- Ge, S.; Agbakpe, M.; Wu, Z.; Kuang, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X. Influences of surface coating, UV irradiation and magnetic field on the algae removal using magnetite nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 1190–1196.

- Lee, K.; Lee, S.Y.; Na, J.G.; Jeon, S.G.; Praveenkumar, R.; Kim, D.M.; Chang, W.S.; Oh, Y.-K. Magnetophoretic harvesting of oleaginous Chlorella sp. by using biocompatible chitosan/magnetic nanoparticle composites. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 149, 575–578.

- Dineshkumar, R.; Paul, A.; Gangopadhyay, M.; Singh, N.P.; Sen, R. Smart and reusable biopolymer nanocomposite for simultaneous microalgal biomass harvesting and disruption: Integrated downstream processing for a sustainable biorefinery. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 5, 852–861.

- Misra, R.; Guldhe, A.; Singh, P.; Rawat, I.; Bux, F. Electrochemical harvesting process for microalgae by using nonsacrificial carbon electrode: A sustainable approach for biodiesel production. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 255, 327–333.

- Uduman, N.; Qi, Y.; Danquah, M.K.; Forde, G.M.; Hoadley, A. Dewatering of microalgal cultures: A major bottleneck to algae-based fuels. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2010, 2, 012701.

- Liu, S.; Hajar, H.A.A.; Riefler, G.; Stuart, B.J. Investigation of electrolytic flocculation for microalga Scenedesmus sp. using aluminum and graphite electrodes. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 38808–38817.

- Rahmani, A.; Zerrouki, D.; Djafer, L.; Ayral, A. Hydrogen recovery from the photovoltaic electroflocculation-flotation process for harvesting Chlorella pyrenoidosa microalgae. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 19591–19596.

- Shi, W.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Q.; Lu, J.; Pan, G.; Hu, L.; Yi, Q. Synergy of flocculation and flotation for microalgae harvesting using aluminium electrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 233, 127–133.

- Gao, S.; Yang, J.; Tian, J.; Ma, F.; Tu, G.; Du, M. Electro-coagulation–flotation process for algae removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 336–343.

- Matos, C.T.; Santos, M.; Nobre, B.P.; Gouveia, L. Nannochloropsis sp. biomass recovery by electro-coagulation for biodiesel and pigment production. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 134, 219–226.

- Vandamme, D.; Pontes Sandra Cláudia, V.; Goiris, K.; Foubert, I.; Pinoy Luc Jozef, J.; Muylaert, K. Evaluation of electro-coagulation-flocculation for harvesting marine and freshwater microalgae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011, 108, 2320–2329.

- Uduman, N.; Bourniquel, V.; Danquah, M.K.; Hoadley, A.F.A. A parametric study of electrocoagulation as a recovery process of marine microalgae for biodiesel production. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 174, 249–257.

- Valero, E.; Álvarez, X.; Cancela, Á.; Sánchez, Á. Harvesting green algae from eutrophic reservoir by electroflocculation and post-use for biodiesel production. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 187, 255–262.