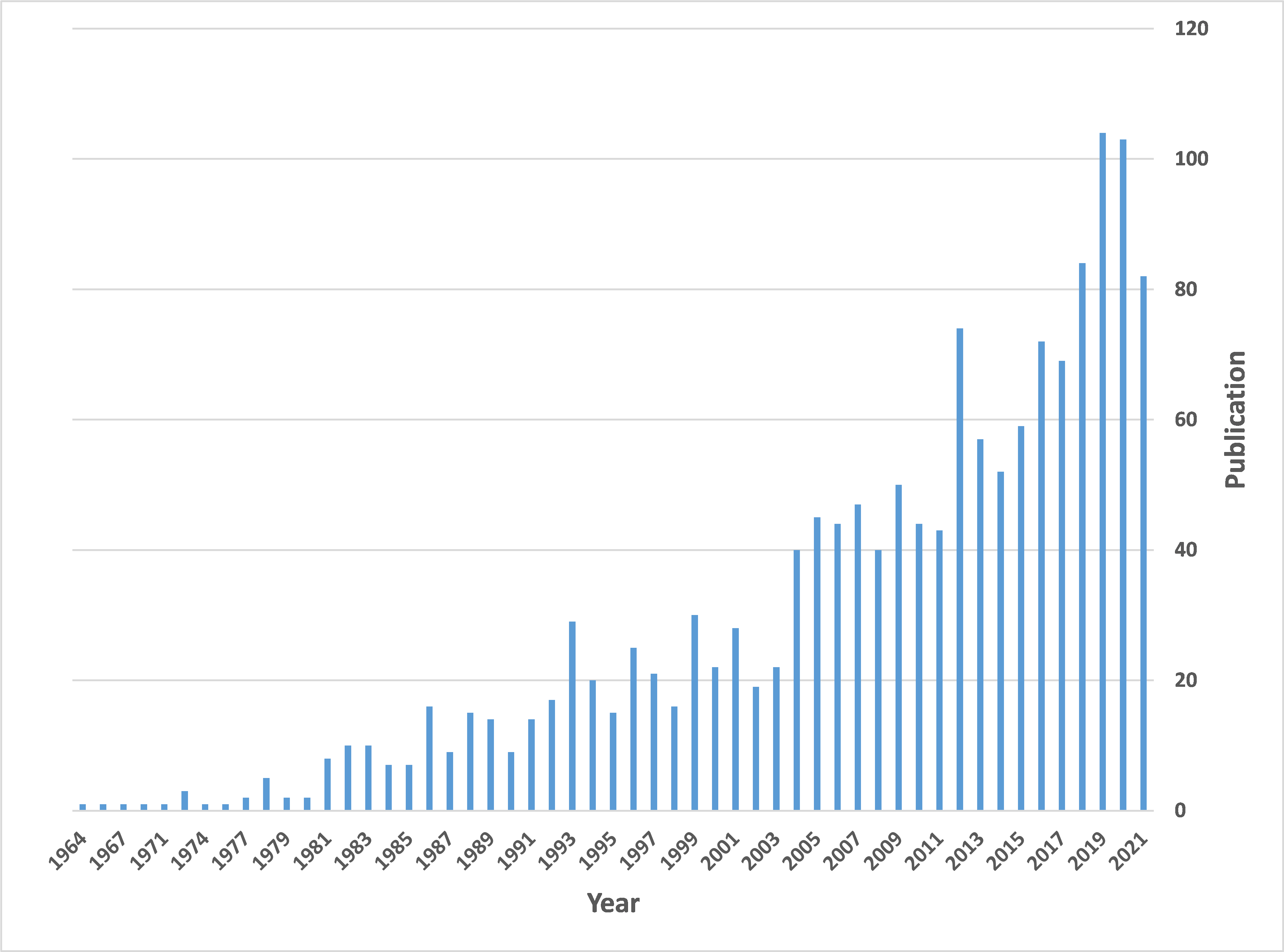

It We is aboutreview the progress in metal phosphate structural chemistry focused on proton conductivity properties and applications. Attention is paid to structure–property relationships, which ultimately determine the potential use of metal phosphates and derivatives in devices relying on proton conduction. The origin of their conducting properties, including both intrinsic and extrinsic conductivity, is rationalized in terms of distinctive structural features and the presence of specific proton carriers or the factors involved in the formation of extended hydrogen-bond networks. To make the exposition of this large class of proton conductor materials more comprehensive, we group/combine metal phosphates by their metal oxidation state, starting with metal (IV) phosphates and pyrophosphates, considering historical rationales and taking into account the accumulated body of knowledge of these compounds. We highlight the main characteristics of super protonic CsH2PO4, its applicability, as well as the affordance of its composite derivatives. We finish by discussing relevant structure–conducting property correlations for divalent and trivalent metal phosphates. Overall, emphasis is placed on materials exhibiting outstanding properties for applications as electrolyte components or single electrolytes in Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells and Intermediate Temperature Fuel Cells.

- metal phosphate

- proton conductivity

- H-bond network

- proton carriers

- super protonic

- metal pyrophosphate

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

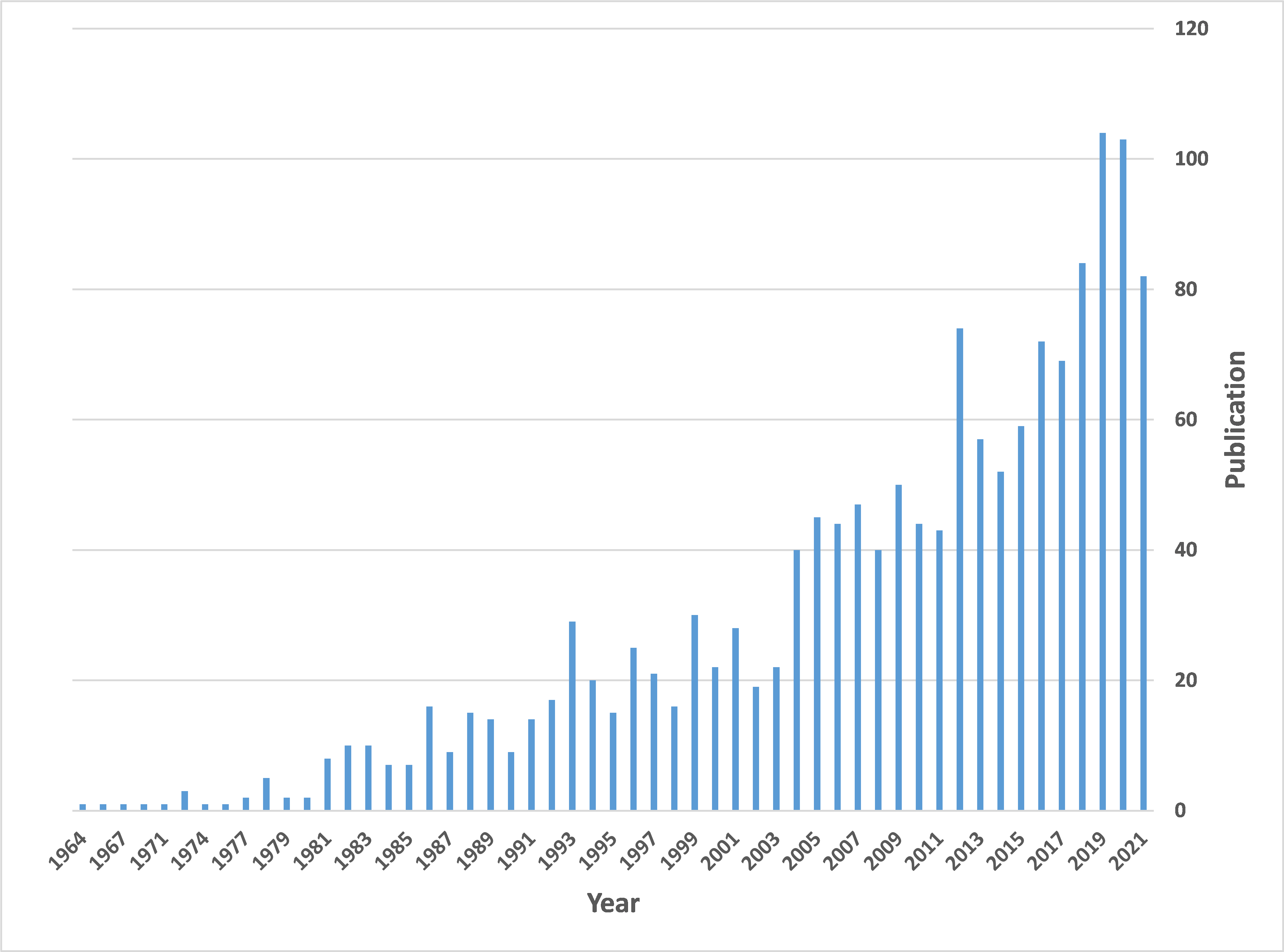

Metal phosphates (MPs) comprise an ample class of structurally versatile acidic solids, with outstanding performances in a wide variety of applications, such as catalysts [1][2][3], fuel cells [4][5][6], batteries [7], biomedical [8], etc. Depending on the metal/phosphate combinations and the synthetic methodologies, MP solids can be prepared in a vast diversity of crystalline forms, from 3D open-frameworks, through layered networks, to 1D polymeric structures.

Metal

2. Tetravalent Metal Phosphates and Pyrophosphates

2.1. Zirconium Phosphates

2.2. Zirconium Phosphate Composite Membranes

2.3. Titanium and Tin(IV) Phosphates

2.4. Other Tetravalent Phosphates

2.5. Tetravalent Pyrophosphates

3. Super Protonic Metal(I) Phosphates

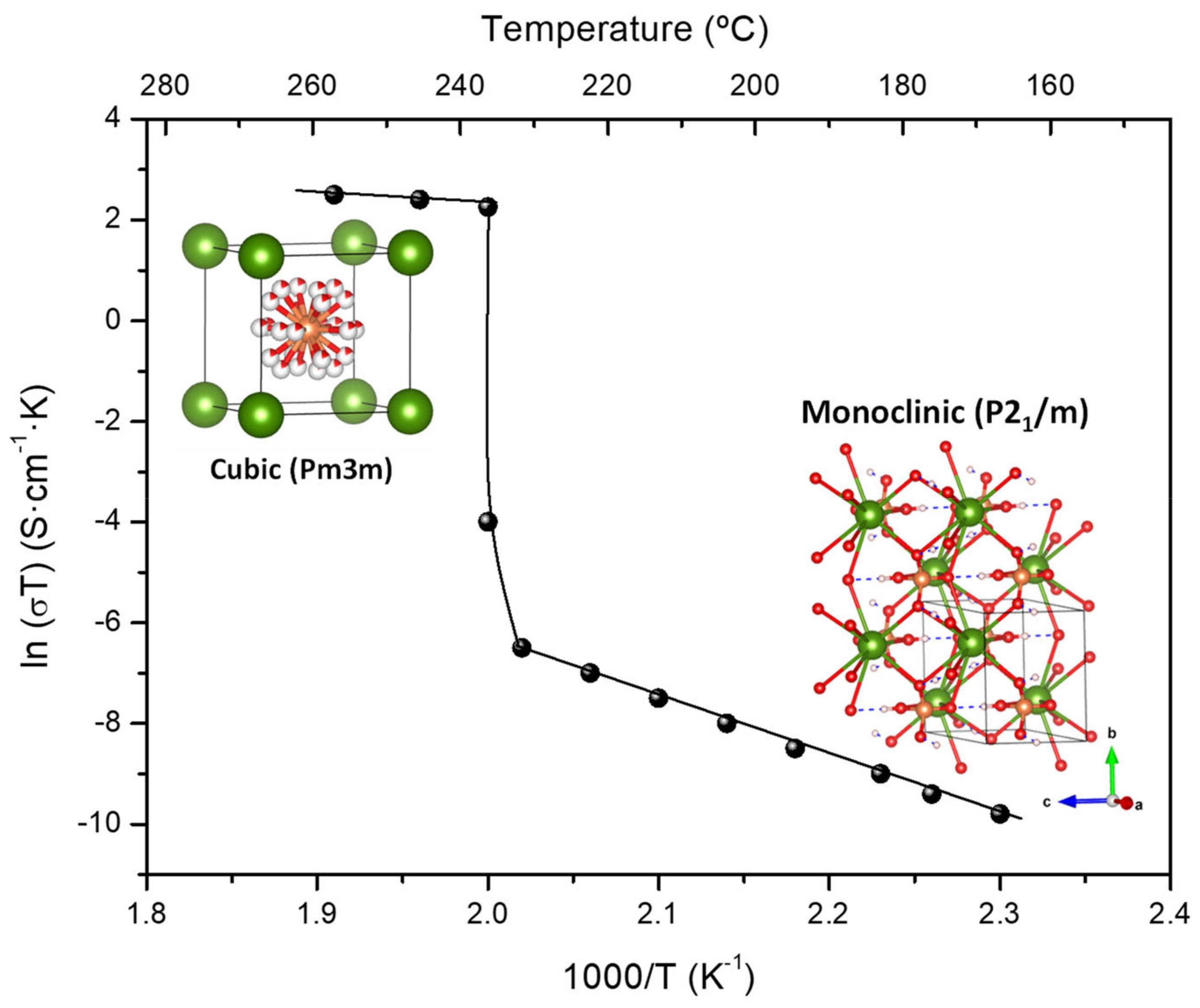

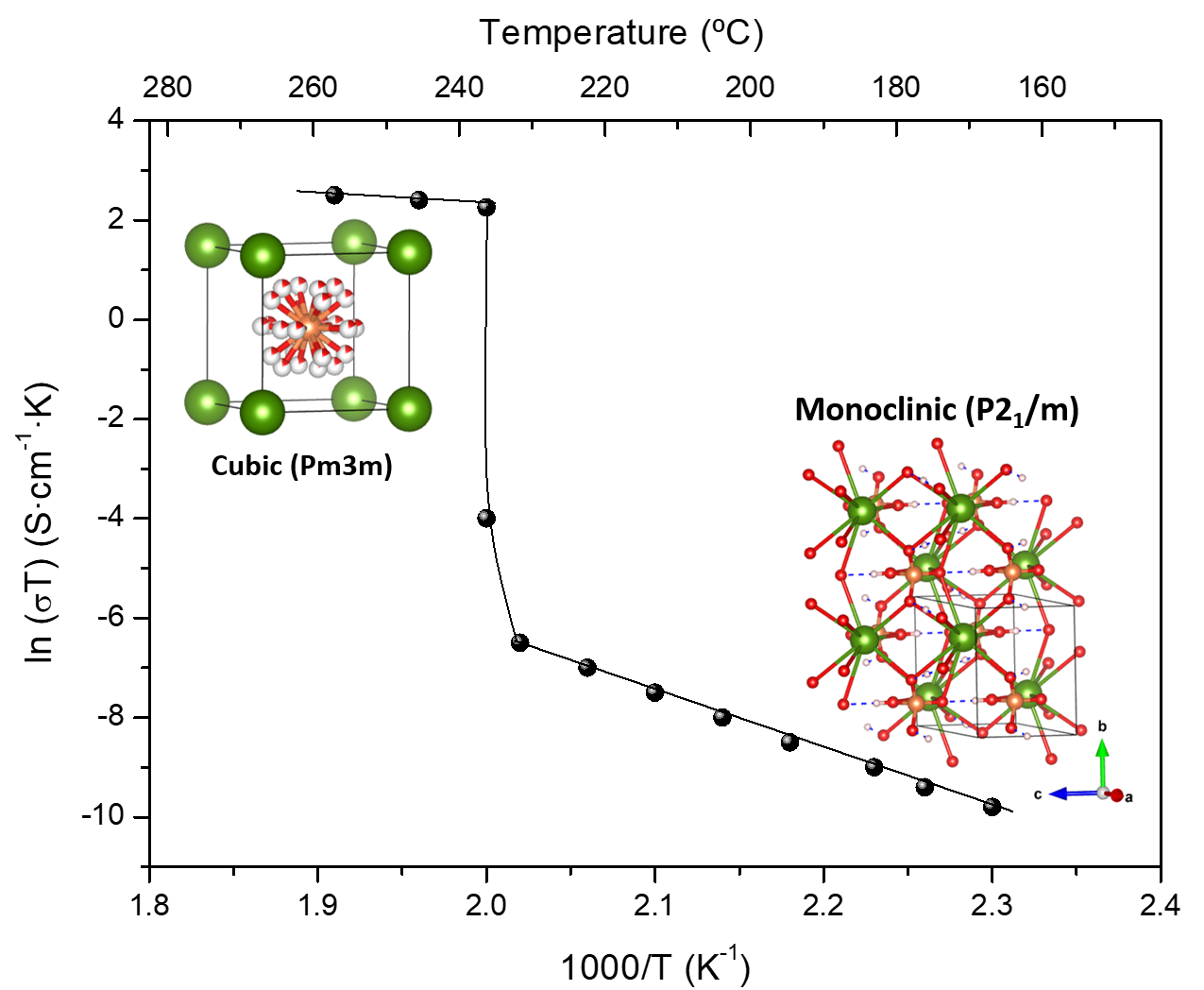

Solid acid proton conductors, with stoichiometry MIHyXO4 (MI = Cs, Rb; X = S, P, Se; y = 1, 2), have received much attention because they exhibit exceptional proton transport properties and can be used as electrolytes in fuel cells operated at intermediate temperatures (120-300 °C). The fundamental characteristics of these materials are the phase transition that occurs in response to heating, cooling or application of pressure [6][119], accompanied by an increase in proton conductivity of several orders of magnitude—referred to as super protonic conductivity (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The characteristic high and low temperature proton conductivity and the corresponding structures for CsH2PO4, adapted from [6][120].

This property has been associated with the delocalization of hydrogen bonds [120]. For CsH2PO4, a proton conductivity of 6 × 10-2 S·cm-1 (Table 1) was measured above 230 °C corresponding to the super protonic cubic (Pm-3m) phase [121] while it drastically drops in the low temperature phases. Recently, from an ab initio molecular dynamics simulation study of the solid acids CsHSeO4, CsHSO4 and CsH2PO4, it was concluded that efficient long-range proton transfer in the high temperature (HT) phases is enabled by the interplay of high proton-transfer rates and frequent anion reorientation.

In these compounds, proton conduction follows a Grotthuss mechanism with proton transfer being associated with structural reorientation [122]. The super protonic conductor CsH2PO4 is stable under humidified conditions (PH2O = 0.4 atm) [6], but it dehydrates to CsPO3, via the transient phase Cs2H2P2O7, at 230-260 °C, according to the relationship log(PH2O/atm) = 6.11(±0.82) - 3.63(±0.42) × 1000/(Tdehy/K) [123].desired product [6].

Imphosphates (MPs) comprise an ample class of structurally versatile acidic sol-ids, with outstrovements in the mechanical and proton conductivity properties, as well as in thermal stability of CsH2PO4-banseding performances in a wide variety of application electrolytes have been addressed by mixing with oxide materials, such as catalysts [1][2][3]zirconia, fuesil cells [4][5][6]ica, alumina, batteriend titania (Table 1). Thus, [7],the b(1-x)Cs3(HSO4)2(H2PO4)/xSiO2 compositedical with x = 0.7 increase the [8],proton acond so ouctivity up to 10–2 S·cm−1 in the range 60–200 °C. Depending on the metal/phosphate combinations and the synthetic methodologies, MP solids can be prepared in a vast diver-sity of crystallinMoreover, the introduction of fine-particle silica reduced the jump in conductivity at the phase-transition temperature and shifted it to lower temperatures. Higher silica contents led to a decrease in the conductivity due to the disruption of conduction paths [132].

The formus, from 3D open-frameworks, through layered networks, to 1De of acid-modified silica confers high thermal stability at low H2O polymearic structures. The advantages oftial pressure while maintaining high proton conductivity (10−3–10−2 S·cm−1, athese 130–250 °C) [134]. A soimilids are, among others, thear trend was found for the composites (1−x)CsH2PO4/xTiO2 and (1−x)CsH2PO4/xZrO2 low (cost and ntents x = 0.1 and 0.2) [135][136]. High performasy prepara-tion, hydrophilic nce was also reported for the composite 8:1:1 CsH2PO4/NandH2PO4/ZrO2, withermally stability and structural designability to a a stable conductivity of 2.23 × 10−2 S·cm−1 for 42 h bertain extent. Additionally, their structures arg measured for the high temperature phase [137]. Nanodiamenable to post-synthesis modifications, including the inonds (ND) are another type of heterogeneous additive giving rise to the (1−x)CsH2PO4-xND (x = 0–0.5) cormporation of ionic or neutral species that significantly affect their functionality and othersites exhibiting enhanced low temperature proton conductivities, while maintaining almost unaltered that of high temperature i[140].

CsH2PO4 comporsitant properties, such as the formation of hydrogen bonding networks or inser-tion ofes based on organic additives have been also intensively investigated. For example, binary mixtures containing N-heterocycles (1,2,4-triazole, benzimidazole and imidazole) displayed enhanced proton carriers.

Donductivity at temperatures below termininghe super proton conduction ic phase transition (2 − 8 × 10−4 S·cm−1 at 174–190 °C) [138]. Another approachanisms is key to de was reported in which the solid acid CsH2PO4 was combigning proton ned with fluoroelastomer p(VDF/HFP), producing high conductor materialive composite membranes (Figure 11−x)CsH2PO4-xp(VDF/HPF) (x = 0. Thus, if a 05–0.25 wt%) with improved mechanical and hydrophobic properties, along with flexibility and reduced thickness.

However, a hicle-type mechanism is needed,gh concentration of p(VDF/HFP) rendered membranes with a reduced proton-containing counter ions, conductivity for the HT phase [141]. By such as hydroniusing the polymer butvar (polyvinyl butyral) [121], composite ions, Nmembranes (1−x)CsH4+,2PO4-xButvar (x < 0.2 wt%) pwerotonated amine groups, ande obtained showing, in a wide range of composition, a protonated organic molecules in general, should be incorporated into the structure. Additionally, the immobilizat conduction behaviour analogous to the pure salt in the high temperature region but with increased low temperature conductivity by three orders of magnitude at x = 0.2.

Table 1. Proton conductivity data for selected monovalent and tetravalent metal phosphates and pyrophosphates.

Compounds/Dimensionality |

Temperature |

( |

° |

C)/RH(%) |

|

Conductivity (S·cm-1) |

Ea (eV) |

Ref. |

||

|

Tetravalent Metal Phosphates |

|

|

|

|

|

ZrP·0.8PrNH2·5H2O/2D |

20/90 |

1.2 × 10-3 |

1.04 |

[50] |

|

Zr(P2O7)0.81(O3POH)0.38/2D |

20/90 |

1.3 × 10-3 |

0.19 |

[51] |

|

Zr(O3POH)0.65(O3PC6H4SO3H)1.35/2D |

100/90 |

7.0 × 10-2 |

--- |

[52] |

|

(NH4)2[ZrF2(HPO4)2]/3D |

90/95 |

1.45 × 10-2 |

0.19 |

[53] |

|

(NH4)5[Zr3(OH)3F6(PO4)2(HPO4)]/3D |

60/98 |

4.41 × 10-2 |

0.33 |

[54] |

|

(NH4)3Zr(H2/3PO4)3/1D |

90/95 |

1.21 × 10-2 |

0.30 |

[55] |

|

Ti2(HPO4)4/1D |

20/95 |

1.2 × 10-3 |

0.13 |

[83] |

|

Ti2O(PO4)2·2H2O (π-TiP)/3D |

90/95 |

1.3 × 10-3 |

0.23 |

[86] |

|

Ti(HPO4)1(O3PC6H4SO3H)0.85(OH)0.30·nH2O/2D |

100/-- |

0.1 |

0.18 |

[117] |

|

Sn(HPO4)2·3H2O/2D |

100/95 |

1.0 × 10-2 |

--- |

[88] |

|

α-ZrP2O7/3D |

300 |

1.0 × 10−4 |

--- |

[49] |

|

(NH4)3Zr(H2/3PO4)3/1D |

180 |

1.45 × 10−3 |

0.26 |

[55] |

|

Tetravalent Pyrophosphates |

|

|

|

|

|

TiP2O7/3D |

100/100 |

4.4 × 10-3 |

0.14 |

[116] |

|

(C6H14N2)[NiV2O6H8(P2O7)2]·2H2O/3D |

60/100 |

2.0 × 10-2 |

0.38 |

[118] |

|

In0.1Sn0.9P2O7/3D |

300 |

0.195 |

--- |

[108] |

|

Ce0.9Mg0.1P2O7/3D |

200 |

4.0 × 10−2 |

--- |

[115] |

|

CeP2O7/3D |

180 |

3.0 × 10−2 |

--- |

[115] |

|

Super protonic Cesium Phosphates |

|

|

|

|

|

CsH2PO4/3D |

>230 |

6.0 × 10−2 |

--- |

[120] |

|

Cs1-xRbxH2PO4/3D |

240 |

3.0 × 10−2 |

0.92 |

[127] |

|

Cs1−xH2+xPO4/3D |

150 |

2.0 × 10−2 |

0.70 |

[141] |

|

(1−x)Cs3(HSO4)2(HPO4)/xSiO2 |

200 |

1.0 × 10−2 |

--- |

[132] |

|

(1-x)CsH2PO4/xTiO2 |

230 |

2.0 × 10−2 |

--- |

[135] |

|

(1-x)CsH2PO4/xZrO2 |

250 |

2.6 × 10−2 |

--- |

[136] |

|

CsH2PO4/NaH2PO4/ZrO2 |

230 |

2.23 × 10−2 |

--- |

[137] |

![]() 4. Divalent and Trivalent Metal Phosphates

4. Divalent and Trivalent Metal Phosphates

4.1. Divalent Metal Phosphates

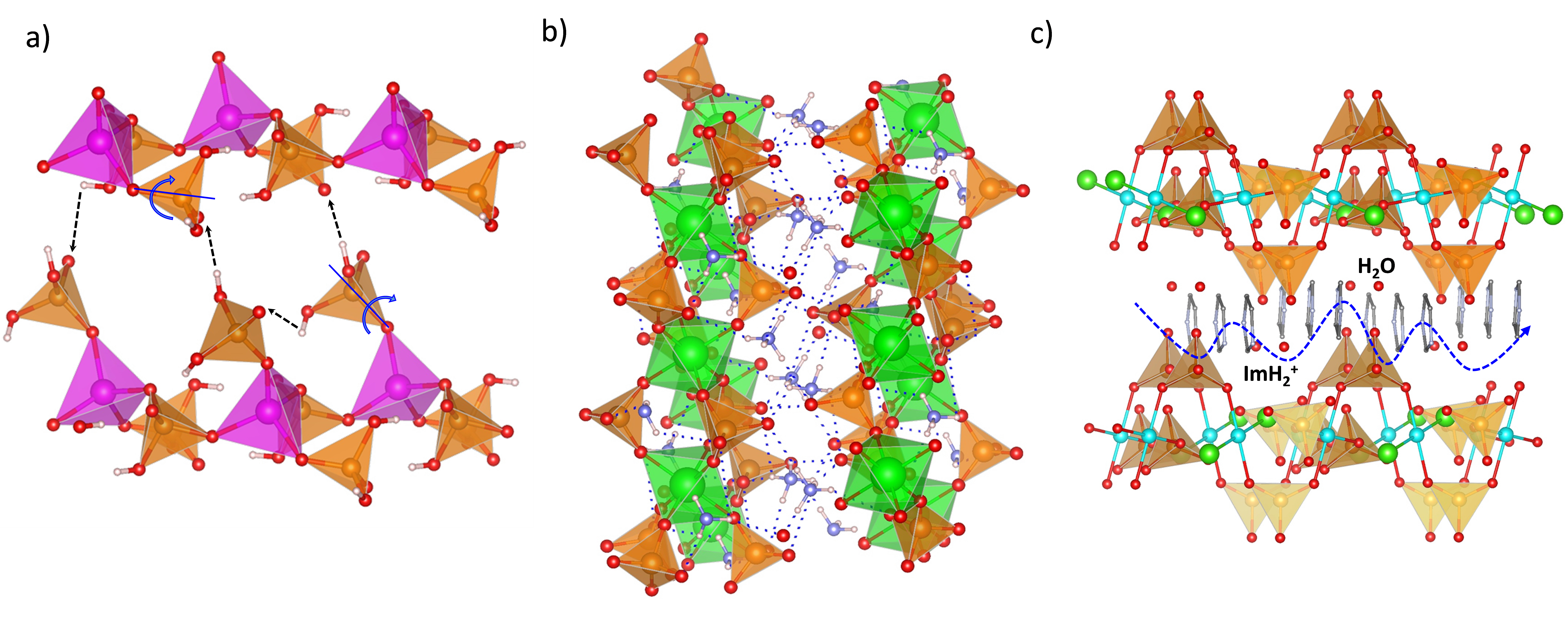

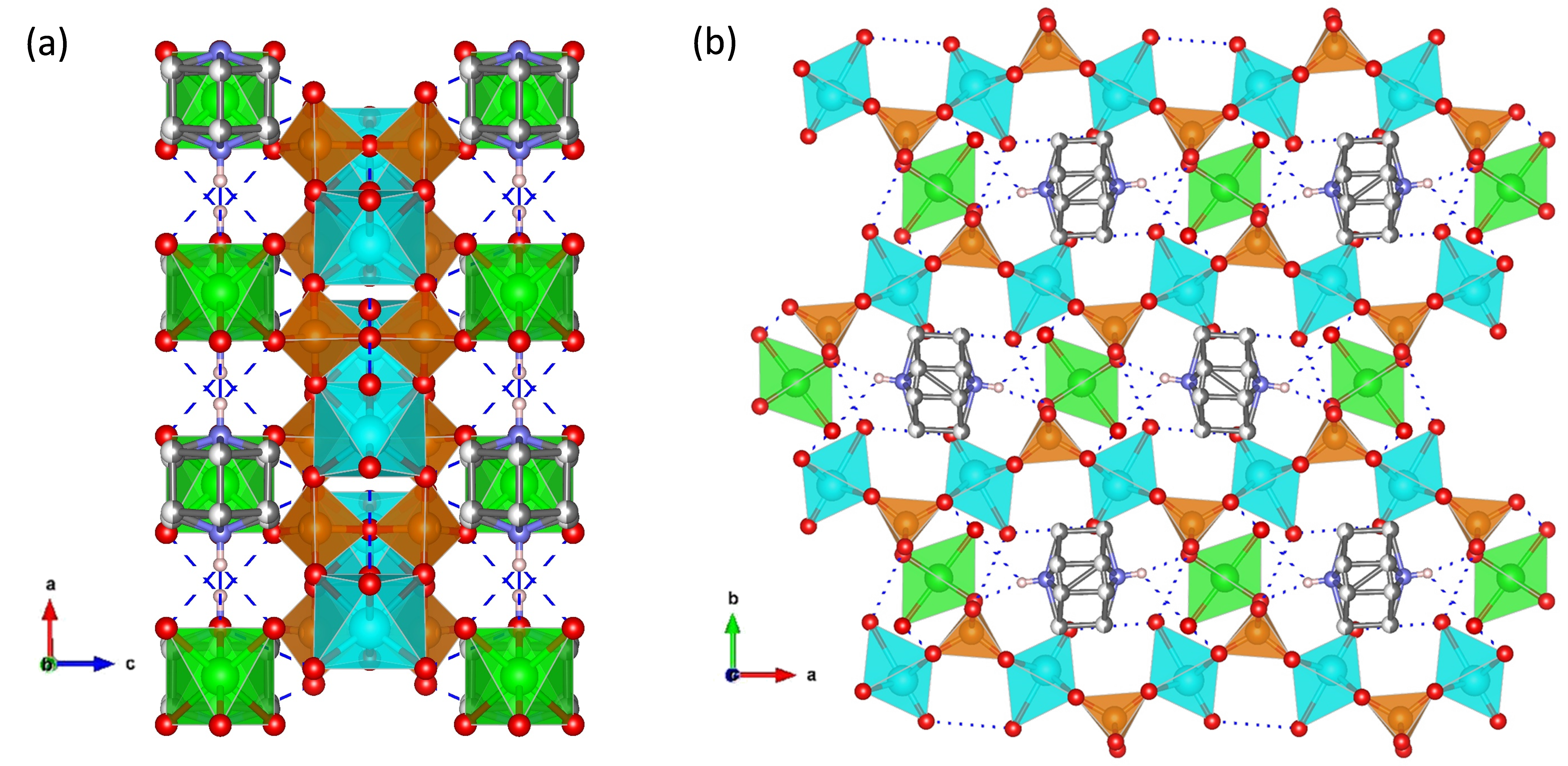

Diovalen of specific functional groups and the corresponding counter ions onto thet transition metal phosphates show a great structural versatility, from 1D polymeric topologies through layered framework could be required. On the other hand, to 3D open-framework structures. Most of these solids exhibiting proton transport by a Grotthuss-type mecha-nism basically consist of continuous H-bond networks that favour H+are synthetized in the presence of organic molecules, which are retained as protonated guest species (amines, iminazole derivatives, etc.), thus, compensating the anionic charge of the inorganic framework. This is cfonduction with low activation energy (Ea). A main drawback for the latter materials is that, above certain temperatures, breaking of the H-bond networks can result, accompanied byrmed by the metal ion, mainly in octahedral or tetrahedral coordination environments, linked to the phosphate groups with different protonated degrees (HxPO4). tThe release of water molecules, which makes the construcpresence of the latter makes possible the formation of permanent H-bondingeffective and extensive hydrogen bond networks with hydrophilic channels or exploring new alternative conductive media necessaryparticipation of water molecules. In addition, protonated guest species and water itself can act as proton carriers, thus, boosting proton conduction [9].

Figur

(Table 1.

Examples of proton transport in phosphate-containing materials: (a) structural reorientation-mediated proton transfer. Zn (magenta), P (orange), O (red) and H (pale pink). (b) hopping through H-bond networks, and (c) carrier-mediated proton conduction. Zn (magenta), Zr (green), Cu (cyan), Cl (light green), P (orange), O (red), N (blue) and H (pale pink) atoms.

Additionally, an extrinsic proton conduction, associated with surface proton transport, can also result from specific chemical modification and/or induced morphological changes, for example, with formation of nanoplatelets or nanorods particles2)

2. Super Protonic Metal(I) Phosphates

.

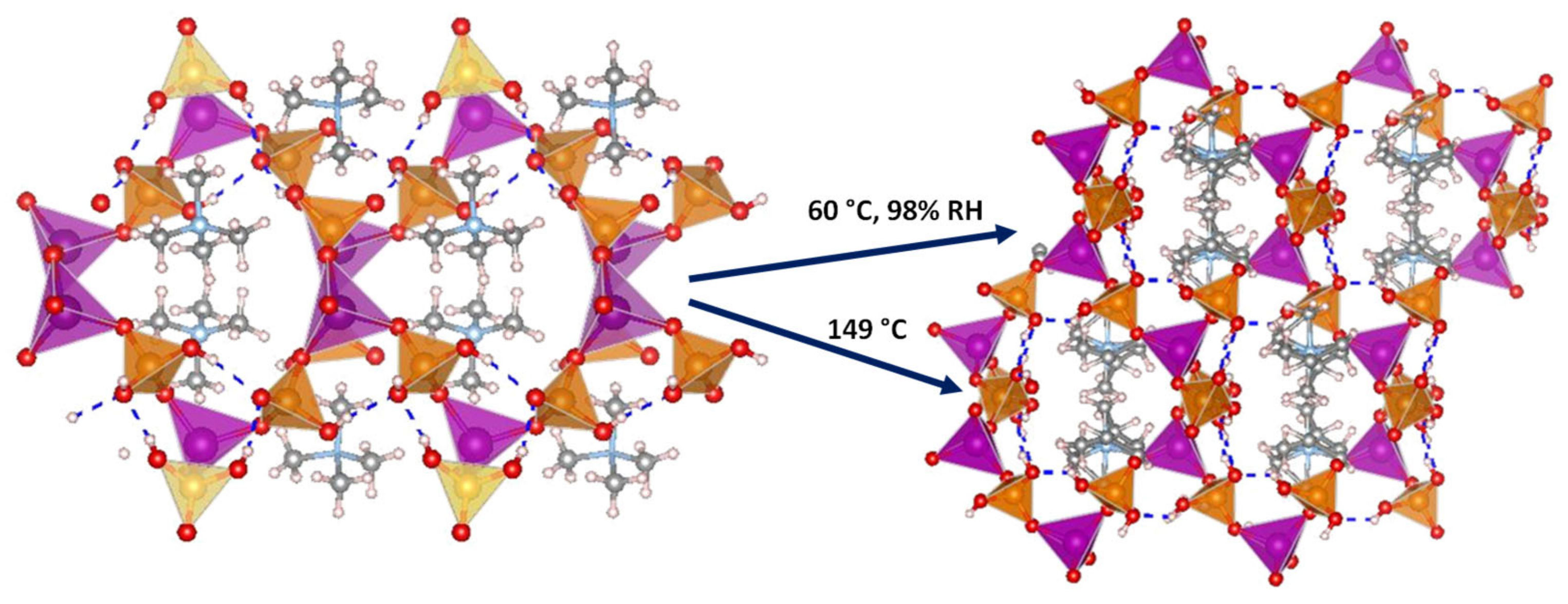

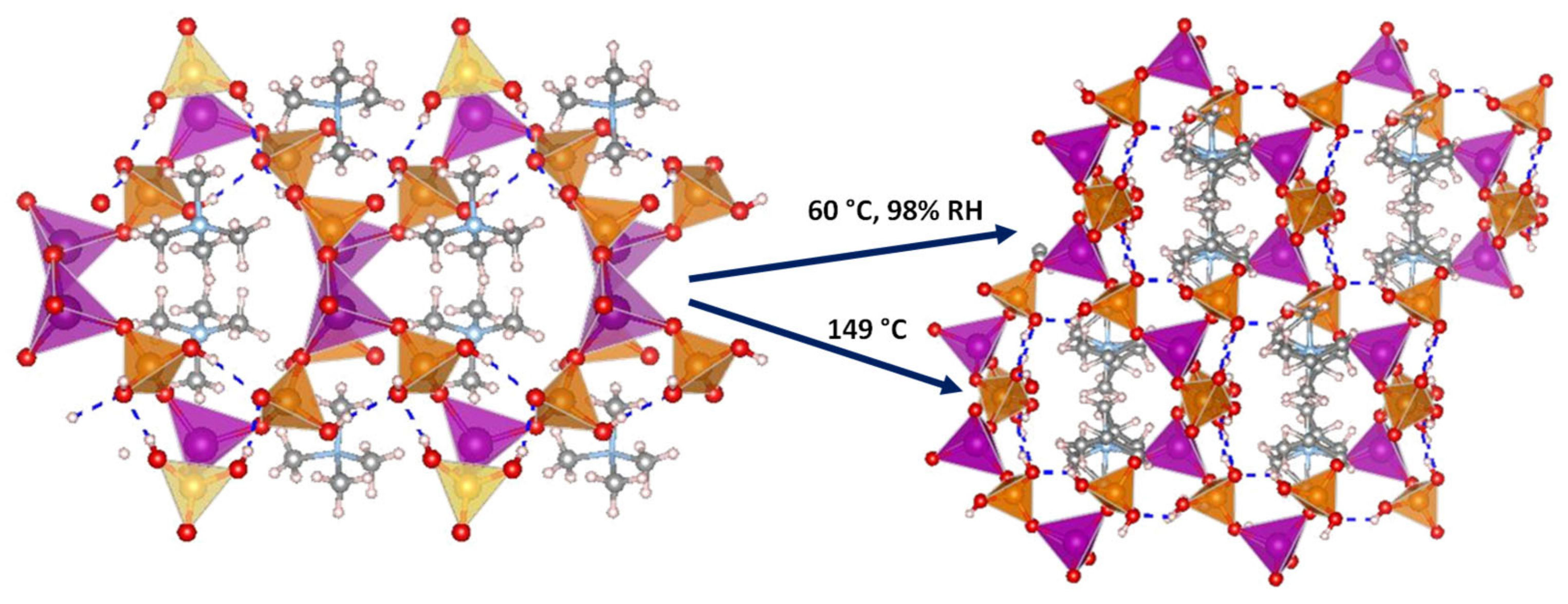

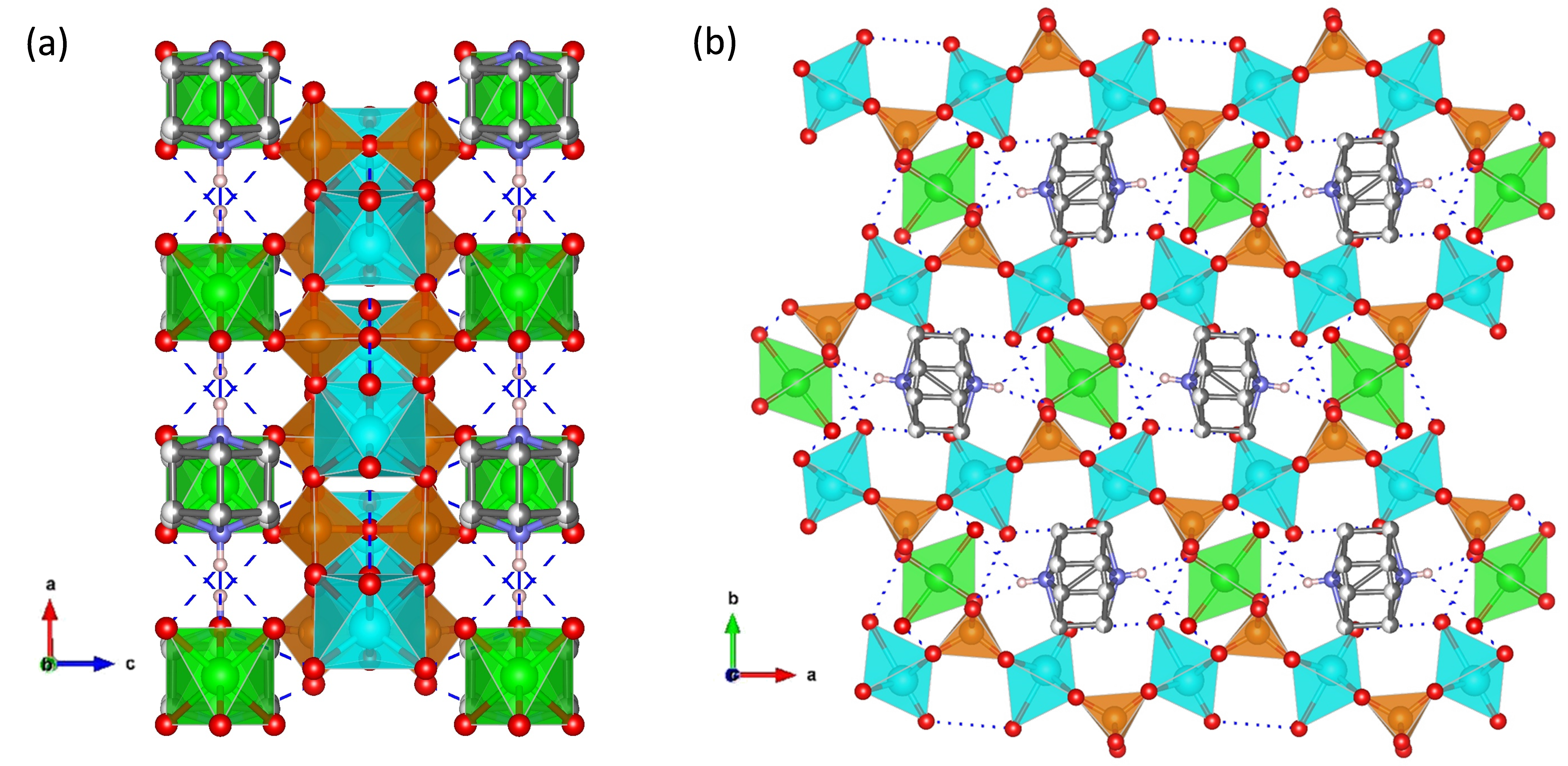

Soeveralid acid proton conductors 3D open-framework M(II) phosphates have been reported [14][143], whith stoichich consist of [CoPO4]∞− ometry MI [Zn2(HyXPO4 )2(MIH2PO4)2]2− =anionic Cs, Rb; X = S, P, Se; y = 1, 2), have received much attention because theyframeworks that contain organic charge-compensating ions in their internal cavities. (C2N2H10)0.5CoPO4 exhibited exceptional proton transport properties and can be used as electrolytes in fuel cells operated at internegligible conductivity in anhydrous conditions; however, it displayed a relatively high water-mediate temperatures (120−3d proton conductivity 2.05 × 100−3 S·cm−1 at 56 °C) and 98% RH. The fundamental characteristics of thesOn the other hand, the solid NMe4·Zn[HPO4][H2PO4] matexperials are the phaseences a structural transition that occurs in response toformation from monoclinic (α) to orthorhombic (β) upon heating, cooling or application of pressure at 149 °C. Both polymorphs contain 12-membered [6][23],rings accompanied by aosed of tetrahedral Zn2+ ioncrease in s linked to proton conductivity of several orders of magnitude—referred to asated phosphate groups without changing super protonicZn-O-P condunectivity (Figure 38).

Figure 3. The characteristic high and low temperature proton conductivity and the corresponding structures for CsH2PO4, adapted from

Figure 8. Irreversible structural transformation in NMe4Zn[HPO4][H2PO4]4 adapted from

. N (sky-blue), O (red), Zn (magenta), P (orange), C (grey) and H (pale pink) atoms.

Thise α property has been associated with the delocalization of hydrogen bondshase transforms into the β phase at high humidity and temperatures above 60 °C, and [24].then For CsH2PO4,eaches a proton conductivity of 61.30 × 10−2 S·cm−1 wat 98% RH, as measured above 230 °C corresp behaviour that might be attributed to the participation of adsorbed water molecules in creating H-bonding to the super protonic networks with effecubtic (Pm−3m) phaseve pathways for proton [25]conduction. wThile ite conductivity drastically drops in the low temperature phases. Recently, from an ab initio molecular dynamics simulation study of the solid acids CsHSeO4,ecreases at 65 °C. In anhydrous conditions, the α phase exhibited a proton conductivity of ~10−4 CsHSO4·cm−1 andt 160 CsH2PO4°C, sit was concluded that efficient long-range proton transfer in the highmilar values were found for other reported zinc phosphates at temperature (HT) phasess between 130 and 190 °C is[12][144][145].

Menabled by the interplay of high proton-transfer rates and fmbrane-electrode assembly prepared with the pelletized solid, gave an observed open circuit voltage (OCV) of 0.92 V at 190 °C measured in a H2/air cequent anion reorientation.

Inll, suggesting that these compounds, protondominant conduction follows a Grotthuss mechanism withve species are protons, and the proton transfer being associated with structural reorieport from anode to cathode takes place through H-bond networks in the pellet.

As ant exationmple of 2D [26].metal Tphosphate super protonicwater-assisted proton conductors, (Cs2H10N2) [Mn2(HPO4)3](H2O), dis stable under humidified conditions (PH2Oplayed a proton conductivity of 1.64 =× 10.4−3 atS·cm)−1 [6], but it ndehydrates to CsPO3, viar 99% RH at 20 °C. This prothe transient phase Cs2H2P2O7, on conductivity was at 230−260 °C, accotrdingibuted to the relationship log(PH2O/atm)formation of = 6.11(±0.82) − 3.63(±0.42) × 1000/(Tdehy/K) [27].

Sdevnseral studie H-bond networks [6][28][29]in thave shown that CsH2PO4 e lattican be employed as, composed of Mn3O13 unithe electrolyte in fuel cells-containing anionic layers [146], whith good long-term stability. Thus, a continuous, stable power gech provide efficient proton-transfer pathways for a Grotthuss-type proton transport at high RH.

Anotheration for both H2/O2 way of improving the proton conductivity in land direct methanol fuel cells operated at ~240 °C was demonstyered divalent metal phosphates is favouring the formation of hydrogen bond networks by ion exchange. For instance [17], partiated fl exchange of Na+ for ethis electrolyte when stabilizedylendiammonium yielded two new crystalline phases, with water particomposition (C2H10N2)xNal1−x[Mn2(PO4)2] pressures(x of ~0.3−0.4 atm. In fact, high performances, corresponding to single cell peak power densities of 415= 0.37 y 0.54), which influenced formation of extended hydrogen bond networks and concomitant increase in proton conductivity, from 2.22 × 10−5 mWS·cm−2,1 for the was achieved for a-synthesized material (in ethylendiammonium form) to 1.3 × 10−2 huS·cmi−1 (x = 0.37) andified 2.1 × H2/O210−2 systeS·cm−1 provided(x = 0.54) with a Cat 99% RH and 30 °C.

ThisH2PO4 elecstrolyte membrane of only 25 µm in thicknessategy of enhancing proton conductivity was further extended successfully [30].

CsH2PO4 ctomp osites based on organic additivther 2D manganese phosphates have[18]. A beeproton also intensively investigated. Vconductivity value as high as 7.72 × 10−2 S·cm−1 warious strategies, including salt modifireached at 30 °C and 99% RH for K+-exchation by cation and anion substitutionnged compounds, which compares well with those [31][32][33][34],of MOF-band mixing with oxidesed open-framework materials [35147][36148][37149][38][39][40][41]. The 1D sor orgalid [Zn3(H2PO4)6(H2O)3](Hbicm) additives(Hbim= [25][42][43][44], have benzimidazolen explored to improve the solid acid performance. The preparation of these derivatives and comp) prepared by mechanochemical synthesis is characterized by presenting a dual-function as proton conductor.

It losies tes involved different synthesis techhe coordinated water by heating transforming into [Zn3(HPO4)6](Hbiquesm), such as sol-gel, impregnation, thin-casting and elewhich exhibits an intrinsic proton conductivity higher than the hydrated form, reaching a value of 1.3 × 10−3 S·cm−1 atrospinning 120 °C, depending on the statebelieved to be due to a rearrangement of the precursor materialsconduction path and the desired product [6].

3. Divalent Metal Phosphates

Divaliquid-like behaviour of benzimidazole molecules. Int transition metal phosphates show a great structural versatility, from 1D polymeric topologies through layered framework to 3D open-framework structures. Most addition, this solid also showed porosity, thus, enabling the adsorption of gaseous methanol that further improved the proton conductivity of these solids are synthetized in the presence of organic molecules, which are ret anhydrous phase. This enhancement of proton conductivity in methanol-adsorbed samples was explained as protonatedby the effective participation of the guest species (amines, iminazole derivatives and so on.), thus, compensatingmolecule in formation of extended hydrogen-bond interactions the[19].

aAnionic charge of the inorganic framework. This is formed by the metal ion, mainly in octahedral or tetrahedral coordination environments, linked to the p ordered-to-disordered structural transformation and its implication in proton conduction were investigated for the 1D copper phosphate gro[ImH2][Cups(H2PO4)2Cl]·H2O (Im = wimith differentdazole). In this structure, the protonated degrees (imidazole (ImHxPO42). and The presence of the latter makes possible the formation of effectivethe water molecule are located in interspaces of the anionic chains [Cu(H2PO4)2Cl]-. aUpond extensive hydrogen bond networks with particip heating a structural transformation of water molecules. In addition, protonated guest species and water itself can act as protonfrom an ordered crystalline state to a disordered state occurred. Highly mobile and structurally disordered H+ carriers, were thus, boostingsupposed to be responsible of the high proton conductivity 2 × 10−2 S·cm−1 at 130 °C, under anhydrous conditions [12150][13][14].

A 1D zinc phosphate-based proton conductor, [Zn3(H2PO4)6(H2O)3](BTA) (BTA = 1,2,3-benzotriazole) has been reported [45151] that exhibits high proton conductivity, 8 × 10−3 S·cm−1 in anhydrous glassy-state (120 °C). The glassy-state, developed via melt-quenching, was suggested to induce isotropic disordered domains that enhanced H+ dynamics and conductive interfaces. In fact, the capability of the glassy-state material as an electrolyte was found suitable for the rechargeable all-solid-state H+ battery operated in a wide range of temperatures from 25 to 110 °C.

A

Focus han example of 2Ds been also put on metal phosphate-based solid solutions [152][153]. Vacancies wcan be generater-assistedd that introduce extra protons into the structure and increase the proton conductors, (C2ion. This effect was investigated for the 1D rubidium and magnesium polyphosphate compound, RbMg1-xH10N2) [Mn2x(HPO43)3](·yH2O), displayed a for which system a maximum proton conductivity of 1.645.5 × 10−3 S·cm−1 was measunder 99% RH at 20 °Cred at 170 °C with a vehicle-type mechanism of H3O+ conduction.

Thise proton conductivity was attributed to results from H-bond interactions between water molecules and corner-sharing PO4 chains that provide formation of dense Hsandwiched edge-sharing RbO6-boMgO6 chaind [152]. Anetworks in the lattice,other example is the solid solution with composed ition Cof M1-xZn3x(H2PO4)2·2H2O13 (0 < x < 1.0), unwhits-contach showed the highest conductivity value, 2.01 × 10−2 S·cm−1 at 140 °C, for a composinting aon Co0.5Zn0.5(H2PO4)2·2H2O [153].

4.2. Trivalent Metal Phosphates

Zeolite-like onic layerspen framework [46],metal(III) wphosphich provide efficieates consist of metal(III) ions-phosphate species (PO43-, HPO42-, H2PO4-) linkages feat proton-transfer pathways for a Grotthuss-type proton transport at high RH.

Seveuring internal cavities, where charge-compensating cations and/or neutral species are located and, thus, dense hydrogen bond networks frequently result. In addition, the ralobust 3D open-inorganic framework M(II) phosphates have been reportendues this porous material with better thermal and chemical stability compared [14][47], which consist of [CoPO4]∞−th porous coordination polymers/metal or [Zn2(HPO4)2(H2PO4)2]2− ganionic frameworks (PCPs/MOFs) [13].

Regarding thao prot conton conductivity (Table 2), alumin organic charge-compium phosphate-based solids are by far the most studied compounds [154][155][156][157][158][159][160][161][162][163][164][165][166][167]. The species insating ions in their internal cavities. (C2ide channels affect in different ways to proton conduction. Thus, while water adsorption is key to assist proton transfer in (NH4)2Al4(PO4)4(H10)0.5CoPO4)·H2O by a hopping mexhibitchanism along H-bond chains [166], densely packed NH4+ ions show negligible conductivity in anhydrous conditiontribution because of hampered migration.

By us;ing an however, it displayed a relativeorganic template-free synthetic methodology, a 3D open-framework aluminophosphate Na6[(AlyPO4)8(OH)6]·8H2O high(JU103) water-meds prepared [158], whiatch showed a proton conductivity 2.05of 3.59 × 10−3 S·cm−1, at 5620 °C and 98% RH. On the other hand, the solid NMe4·Zn[ It was argued that the enhanced conductivity of the as-synthesized material as compared to its NHPO4][H2PO4]+- or Ag+-expchangeriences a structural trd forms is indicative of a beneficial effect of hydrated Na+ ionsfo in genermation from monocating proton-transfer pathways. The 3D cesium silicoaluminophosphate, Cs2(Al0.875Sin0.125)4(P0.875Sic 0.125O4)4(αHPO4), to orthorhombibelonging to the structural family of SAPOs, was shown to exhibit a remarkable proton conductivity of 1.70 × 10−4 S·cm−1 (β)at upon heating at 149 °C. Both polylow temperature and RH (20 °C and 30%, respectively) [168][169].

Several 2D aluminorphs contain 12-membered ringphosphates have been reported as proton conductors [154][156]. These composed of tetrahedral Zunds (denoted as AlPO-CJ70/2) are structurally characterized by displaying an2+ anions ic layer: [Alink2P3O12]3-, formed by alto protonernating Al3+ atend phosphate groups without changing Zn-O-P connectivity (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Irreversible structural transformation in NMe4Zn[HPO4][H2PO4]4 adapted from [47]. N (sky-blue), O (red), Zn (magenta), P (orange), C (grey) and H (pale pink) atoms.

The α phase transforms into the β phase at high humidity and temperatures above 60 °C, and then reaches a proton conductivity of 1.30 × 10−2 S·cm−1 at 98% RH, a behaviour that might be attributed to the participation of adsorbed water molecules in creating H-bonding networks with effective pathways for proton conduction. The conductivity drastically decreases at 65 °C. In anhydrous conditions, the α phase exhibited a proton conductivity of ~10−4 S·cm−1 at 160 °C, similar values were found for other reported zinc phosphates at temperatures between 130 and 190 °C [12][48][49].

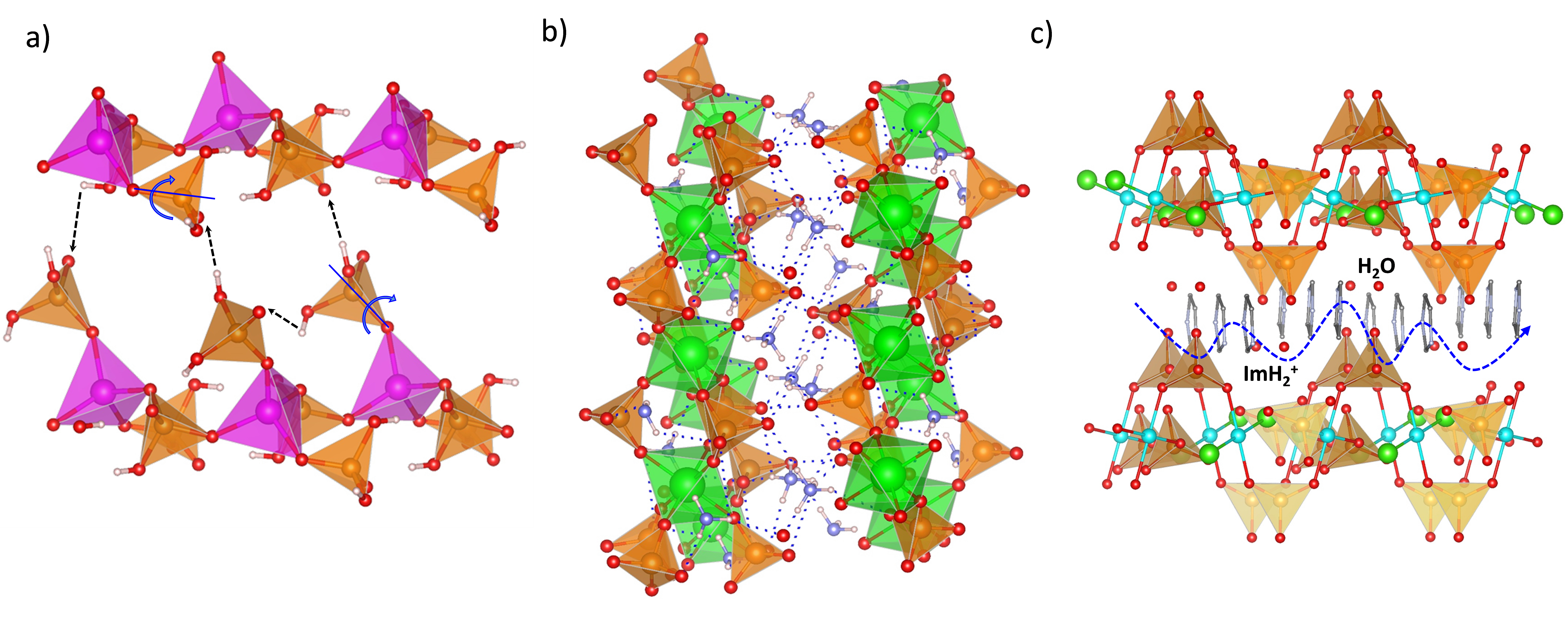

4. Trivalent Metal Phosphates

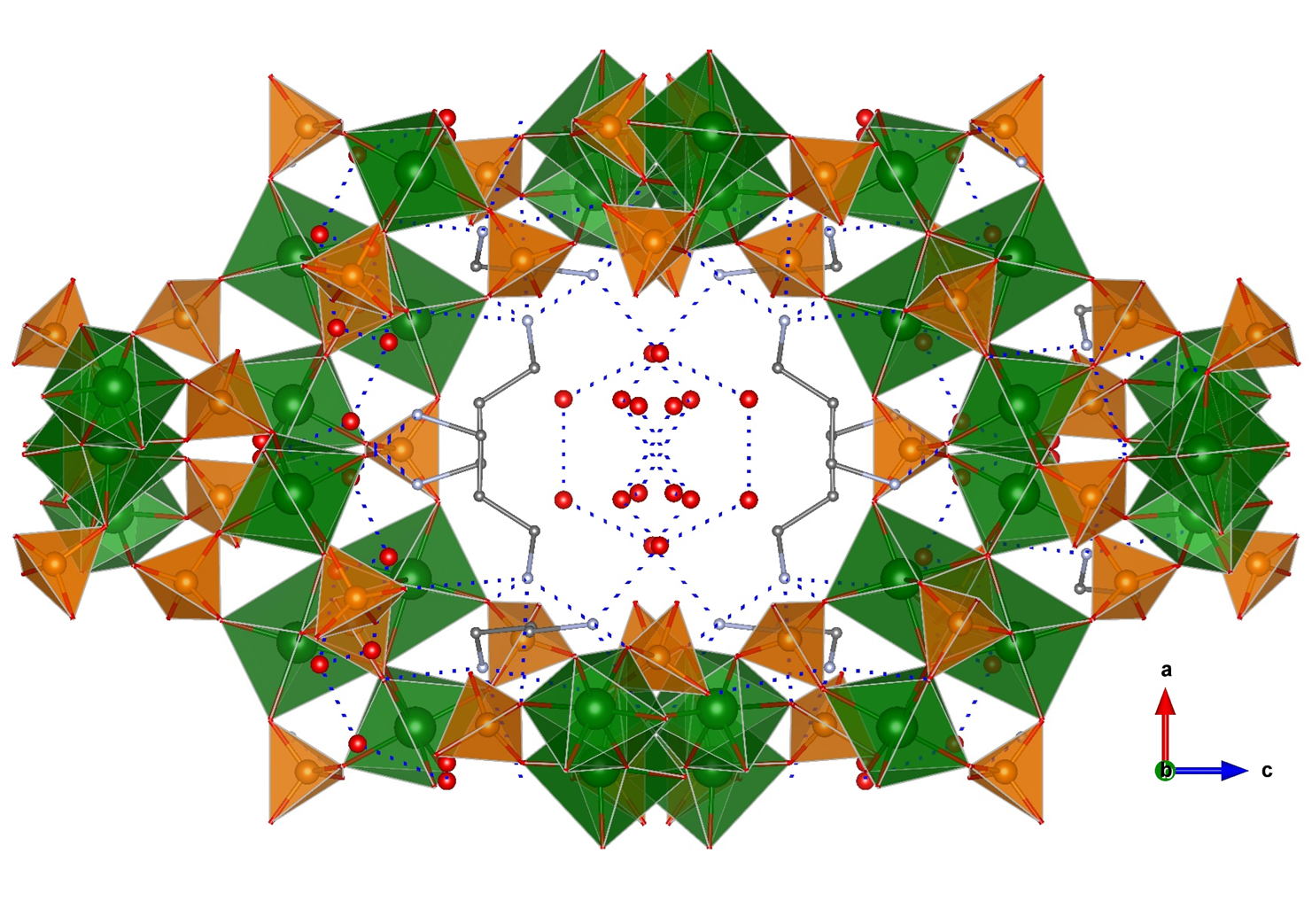

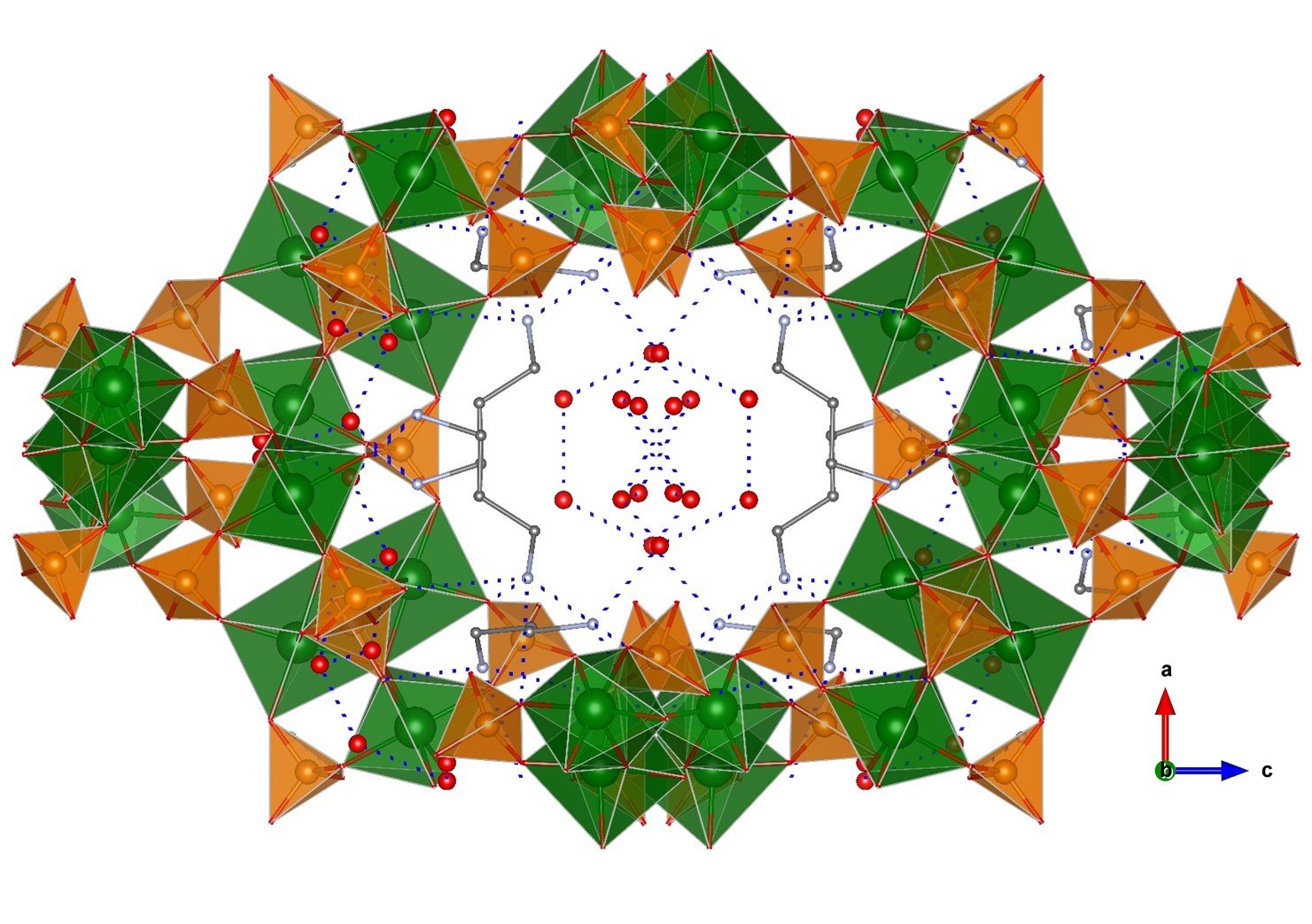

A few examples of phosphate-based proton conductors of other trivalent metals do exist. Among them, two Fe(III) phosphates, 1D (C4H12N2)1.5[Fe2(OH)(H2PO4)(HPO4)2(PO4)]·0.5H2O [13] and 3D open-framework iron(III) phosphate (NH3(CH2)3NH3)2[Fe4(OH)3(HPO4)2(PO4)3]·4H2O [50], have been reported. Both compounds contain Fe4O20 tetramers as a common structural feature. The 1D solid is composed of chains of tetramers bridged by PO43- groups and having terminal H2PO4- and HPO42- groups [51], while piperazinium cations and water molecules are disorderly situated in between chains. This arrangement gives rise to extended hydrogen bonding interactions and hence proton conducting pathways. The proton conductivity measured at 40 °C and 99% RH was 5.14 × 10−4 S·cm−1, and it was maintained upon dispersion of this solid in PVDF [13]. In the case of the 3D solid, infinite chains of interconnected tetramers are interlinked, in turn by phosphate groups that generate large tunnels (Figure 5). The diprotonated 1,3-diaminopropane and water molecules, localized inside tunnels, form an extended hydrogen bond network with the P–OH groups pointing toward cavities. These interactions favour proton hopping, the measured proton conductivity being of 8.0 × 10−4 S·cm−1, at 44 °C and 99% RH, and with an Ea of 0.32 eV [52]. Furthermore, the proton conductivity of this compound increased up to 5 × 10−2 S·cm−1 at 40 °C upon exposure to aqua-ammonia vapors from 1 M NH3·H2O solution. This result confirms this treatment as an effective way of enhancing proton conductivity, which has been elsewhere demonstrated for the case of coordination polymers [53][54].

Figure 5. Open-framework structure of (NH3(CH2)3NH3)2[Fe4(OH)3(HPO4)2(PO4)3]·4H2O showing guest species inside channels and H-bond interactions. Fe (green), O (red), P (orange), and C (grey) atoms.

Other trivalent metal phosphates have been reported, for example, BPOx [55] and CePO4 [56]. The former exhibited a proton conductivity of 7.9 × 10−2 S·cm−1 as self-supported electrolyte and 4.5 × 10−2 S·cm−1 as (PBI)−4BPOx composite membrane, measured at 150 °C and 5% RH, but structure/conductivity correlations were not established because of its amorphous nature.

There are only a few examples of metal(III) pyrophosphates displaying proton conductivity. Among them is the open framework magnesium aluminophosphate MgAlP2O7(OH)(H2O)2 (JU102) [57]. Its structure is composed of tetrahedral Al3+ and octahedral Mg2+ ions coordinated by pyrophosphate ions. This connectivity results in an open framework with unidirectional 8-ring channels. The proton conduction properties originate from the existence of an H-bond network in which coordinated water molecules participate. Thus, the proton conductivity measured at 55 °C on water-immersed samples was 3.86 × 10−4 S·cm−1, which raised to 1.19 × 10−3 S·cm−1 when calcined at 250 °C and measured at the same conditions, while the Ea value hardly changed from 0.16 to 0.2 eV. This behaviour was explained as being due to a dehydration–rehydration process that enhances proton conductivity by altering the H-bonding network and the pathway of proton transfer.

Another example of 3D open framework metal(III) pyrophosphate is the compound NH4TiP2O7 [58]. The structure of this solid is composed of negatively charged [TiP4O12]− layers, forming one-dimensional six-membered ring channels, where the NH4+ ions are located. Its proton conductivity increased from 10−6 S·cm−1 under anhydrous conditions to 10−3 S·cm−1 at full-hydration conditions and 84 °C. The low Ea value, 0.17 eV, characteristic of a Grotthuss-type proton-transfer mechanism, was associated with the role played by the NH4+ ions in the channels as proton donors and promoters of proton migration. A drop in proton conductivity was observed when the triclinic TiP2O7 phase formed by thermal decomposition of NH4TiP2O7 [58].

5. Tetravalent Metal Phosphates and Pyrophosphates

5.1. Zirconium Phosphates

Torus tetrahedra, which is charge-compensated by N,N-dimethylbenzylamine or α-methylbenzylamine ions, respectively. In these prototype of layered metal(IV) phosphates is zirlayered structures, extended H-bond networks are formed through interactions of the amine N atoms, H2O moleconium hydrogenles and protruding phosphate, which presents mainly three topologies, known as the forms groups of the anionic layer. Consequently, water-mediated proton conduction processes occurred upon immersion in water, with σ values around α:10−3 Zr(HPO4)2S·H2O (α-ZrP)cm−1, γ:at Zr(PO4)(O2P(OH)2)80 2H2O (γ-ZrP)°C, and λ:Ea (Zr(PO4)XY, X= hvalidues, OH-, of 0.16−0.2 HSO4-eV, typicand Y=DMTHUS, H2O, l of and so on) (λ-ZrP)Grotthuss-type proton-transfer mechanism.

α-ZrPBy is the most thermal and hydrolytically stable phase and, thusfollowing a synthetic route in which methylimidazolium dihydrogenphosphate was used as a solvent, structure-directing agent, and a phosphorus source, the mosolid (C4H7N2)(C3H4N2)2·Al3(PO4)4·0.5H2O (SCU−2) was obtained [164]. Its layered studied compound following ructure, built up from corner-sharing Al3+ and PV tetrahe pioneering works by Giulio Alberti and Abraham Clearfield groupsdra, features 8-member rings where guest imidazolium ions and water molecules are hosted. At 85 °C and 98% RH, this solid showed a proton conductivity of [59][60][61]5.

9 × 10

Due to the higher stability of the α form, proton conductivity studies have been conducted mainly with this phase. Typical values of 10−6–10−4 S·cm−1 have been determined at RT and 90% RH with activation energy (Ea) ranging between 0.26 (90% RH) and 0.52 eV (5% RH). This conductivity originates from surface transport and is dominated by surface hydration since the long distance between adjacent P-OH groups hinders proton diffusion along the internal layer surface [62].

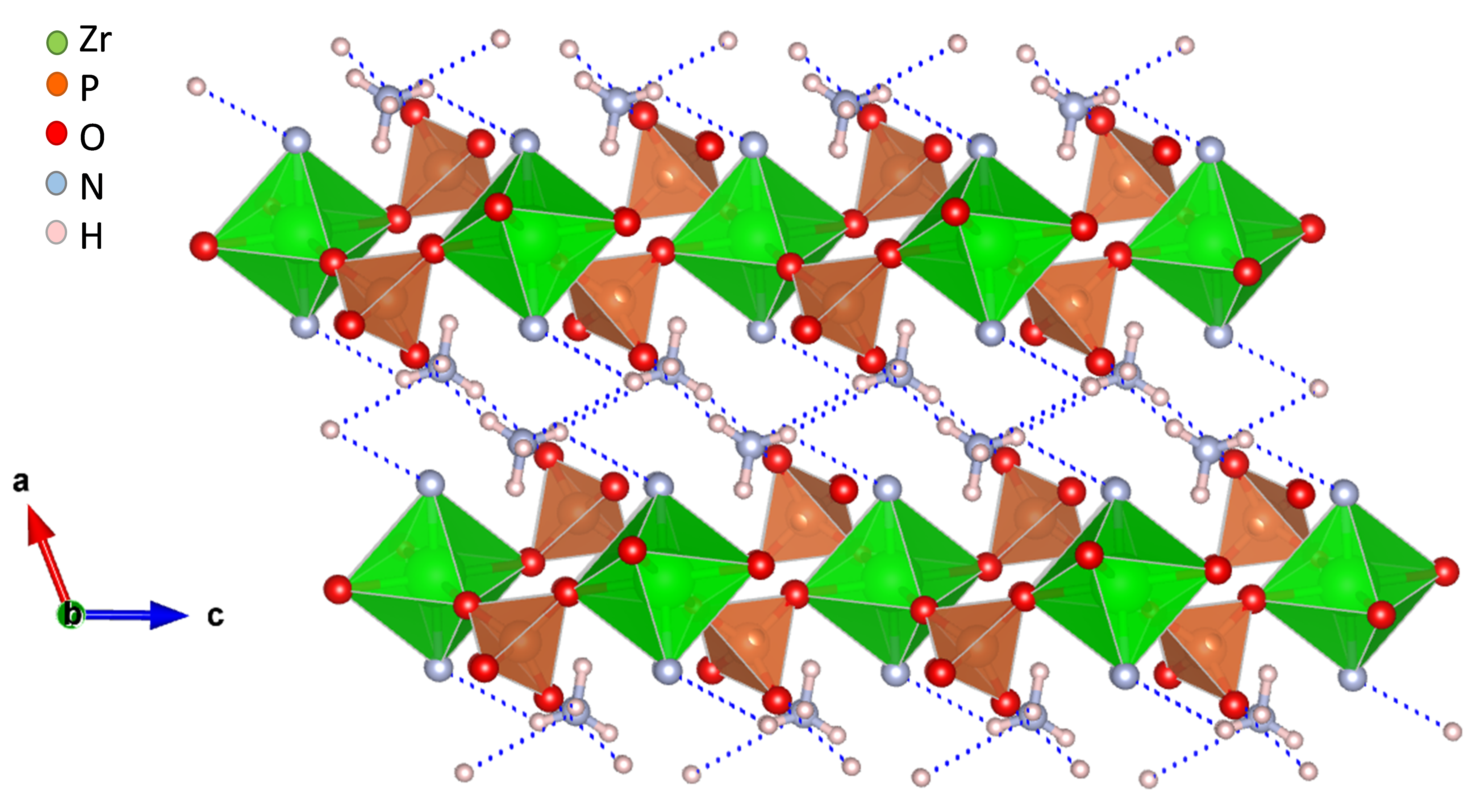

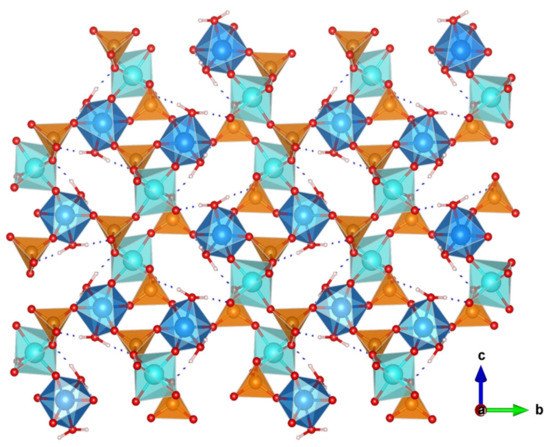

The great versatility of zirconium phosphate preparation under numerous experimental conditions, has been exploited to synthesize various novel derivatives, which displayed remarkable proton conductivity properties. Two examples are layered (NH4)2[ZrF2(HPO4)2] [63] and the 3D open framework zirconium phosphate (NH4)5[Zr3(OH)3F6(PO4)2(HPO4)] [64]. In both structures, the participation of NH4+ ions in the formation of extended hydrogen-bond networks (Figure 6) resulted in proton conductivities of 1.45 × 10−2 S·cm−1 (at 90 °C and 95% RH) and 4.41 × 10−2 S·cm−1 (at 60 °C and 98% RH), respectively. From the Ea values found, 0.19 and 0.33 eV, respectively, a Grotthuss-type proton-transfer mechanism was inferred for these materials.

Figure 6. Layered structure of compound (NH4)2[ZrF2(HPO4)2] and possible proton-transfer pathways (adapted from [63]).

A one-dimensional zirconium phosphate, (NH4)3Zr(H2/3PO4)3, consisting of anionic [Zr(H2/3PO4)3]n3n

S·cm

− chains bonded to charge-compensating NH4+ ions was reported [65]. In this structure, the phosphates groups are disorderly protonated, while NH4+ ions occupy ordered positions in between adjacent chains (Figure 7). This arrangement generates H-bonding infinite chains of acid–base pairs (N-H···O-P) that lead to a high proton conductivity in anhydrous state of 1.45 × 10−3 S·cm−1, at 180 °C. This material also showed a remarkable high performance in PEMFC and DMFC under operation conditions.

5.2. Titanium and Tin(IV) Phosphates.

and Structurally, titanium(IV) phosphates are more diverse than ZrP, given that structures containing an oxo/hydroxyl ligand or mixed-valence (T low activation energy (0.20 eV), characteristic of a Grotthuss-type proton-transfer mechanism. An efficient pathway for the proton transfer was attributed to the hydrogen bond network established between the iIII/TmiIV) titdanzolium ions have been reported. In addition to the zirconiuand water molecules interacting with the host framework.

A few examples of phosphate analogues, α--based proton [66] acond γ-TiP [67], uctwo morers of other layered titanium trivalent metals do exist. Among them, two Fe(III) phosphates, Ti1D (C4H12N2)1.5[Fe2(OH)(H2POH4)(HPO4)2(PO4)]·20.5H2O [6813] and T3D open-framework iron(III) phosphate (NH3(CH2)3NH3)2[Fe4(OH)3(HPO4)2(PO4)23]·24H2O [170], harve knowbeen [69]. Furthermore, the mixed-valencported. Both compounds contain Fe4O20 tietanium phosphate Tramers as a common structural feature. The 1D soliIIITd iIV(HPO4)4·C2N2H9·H2Os compontains micsed of chains of tetramers bridged by PO43- grouporous channels and having terminal H2PO4- and HPO42- groups [70171], whilere monoprotonated ethylenediamine and lattice water are accommodated, which favours its transformation into a porous phase, T piperazinium cations and water molecules are disorderly situated in between chains. This arrangement gives rise to extended hydrogen bonding interactions and hence proton conducting pathways. The proton conductivi2(HPO4)4,ty measured at 6040 °C with a 3Dand 99% RH was 5.14 × 10−4 struS·cm−1, and iture similar to that of τ-Zr(HPO4)2was maintained upon dispersion of this solid in PVDF [7113].

In Tthe crystal structure of two other open-frameworks Ti2Oase of the 3D solid, infinite chains of interconnected tetramers are interlinked, in turn by phosphate groups that generate large tunnels (PO4Figure 9)2·2H2O. The dipolymorphs (ρ-TiP and π-TiP) has been reportedrotonated 1,3-diaminopropane and water molecules, localized inside tunnels, form an extended hydrogen bond network with the [72][73].P–OH Fibgrous ρ-TiP and π-TiP crystallize in triclinic and monoclinic unit cells, respectively, and areps pointing toward cavities. These interactions favour proton hopping, the measured proton conductivity being of 8.0 × 10−4 S·compose−1, at 44 °C and of99% TiO6RH, and TwiO4(H2O)2th an Ea ocf 0.32 eV [172]. Furtahedra bridged through the orthophosphrmore, the proton conductivity of this compound increased up to 5 × 10−2 S·cm−1 at 40 °C upon e groups (Figure 8)xposure to aqua-ammonia vapors from 1 M NH3·H2O solution. This resultype of connectivity creates two types of 1D channels running parallel to the direction of confirms this treatment as an effective way of enhancing proton conductivity, which has been elsewhere demonstrated for the case of coordination polymers [173][174]. tThe fibre groobserved variation of Ea with [72][73][74].the 31Pammonia MAS-NMR spconcectroscopy studies revealentration also suggested that π-TiPNH3, has capabilitywell as H2O, mof adsorbing superficiallylecules contribute to create protonated phosphate species (-transfer pathways, by a Grotthuss mechanism. H3PO4/H2PO4-/HPO42-)owever, when ammonich affectsa concentrations were lower than 0.5 M, the proton conductivity properties as confirmed by AC impedancon mechanism tended to be vehicle-type one measurements.

.

Figure 9. ThOpe isomorphous series of layn-framework structure of (NH3(CH2)3NH3)2[Fered α-metal4(IVOH) phosphates [M3(IVHPO4) = Zr, Ti, Sn2(PO4)3]·4H2O showing gued appreciable differences in the hydrogen st species inside channels and H-bond interaction of the lattice water with the layers, associated with a variable layer corrugation degree along the series; α-TiP and α-SnP displaying H-bonds stronger than the prototype α-ZrP [75]s. Fe (green), O (red), P (orange), which, in turn, might have significant implications in making internal surfaces accessible to proton conduction pathnd C (grey) atoms.

Recent studies carried out on a nanolayered γ-type tin phosphate, Sn(HPO4)2·3H2O, have revealed that this solid could be obtained in a water-delaminated form, which showed a high proton conductivity of ~1 × 10−2 S·cm−1 at 100 °C and 95% RH. This high value was attributed to strong H-bonds between water and the SnP layers, in combination with a high surface area of 223 m2·g−1 [76].

Other tetravalent phosphates such as silicophosphates with POH groups have received attention as proton-conducting electrolytes [77] but its solid-state structural characterization is elusive, at least, under conditions similar to those used in operating fuel cells [78].

5.3.

Tetravalent Pyrophosphatesble 2.

Proton conductivity data for selected Tdivaletrant and trivalent metal pyrophosphates.

Compounds/Dimensionality |

Temperature |

( |

° |

C)/RH(%) |

Conductivity |

(S·cm |

-1 |

) |

Ea |

(eV) |

|

Ref. |

Divalent Metal Phosphates |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

(C2N2H10)0.5CoPO4/3D |

56/98 |

2.05 × 10-3 |

1.01 |

[143] |

|

|

NMe4·Zn[HPO4][H2PO4] (β phase)/3D |

60/98 |

1.30 × 10-2 |

0.92 |

[14] |

|

|

(C2H10N2) [Mn2(HPO4)3](H2O)/2D |

20/99 |

1.64 × 10-3 |

0.22 |

[146] |

|

|

(C2H10N2)xNa1−x[Mn2(PO4)2]/2D |

30/99 |

2.1 × 10-2 |

0.14 |

[17] |

|

|

(C2H10N2)1-xKx[Mn2(PO4)2]·2H2O/2D |

30/99 |

7.72 × 10-2 |

0.18 |

[18] |

|

|

(C2H10N2)1-xKx[Mn2(HPO4)3] (H2O)/2D |

30/99 |

0.85 × 10-2 |

0.081 |

[18] |

|

|

[Zn3(H2PO4)6(H2O)3](Hbim)/1D |

120 |

|

1.3 × 10−3 |

0.50 |

[19] |

|

[ImH2][Cu(H2PO4)2Cl]·H2O/1D |

130 |

|

2.0 × 10−2 |

0.1 |

[150] |

|

[Zn3(H2PO4)6(H2O)3](BTA)/1D |

120 |

|

8.0 × 10−3 |

0.39 |

[151] |

|

RbMg0.9H0.2(PO3)3·yH2O/1D |

170 |

|

5.5 × 10−3 |

--- |

[152] |

|

Co0.5Zn0.5(H2PO4)2·2H2O/1D |

140 |

|

2.01×10−2 |

--- |

[153] |

|

Trivalent Metal Phosphates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Na6[(AlPO4)8(OH)6]·8H2O/3D |

20/98 |

|

3.59×10-3 |

0.21 |

[158] |

|

[C9H14N]8[H2O]4·[Al8P12O48H4]/2D |

80, in water |

|

9.25×10-4 |

0.16 |

[154] |

|

[R-,S-C8H12N]8[H2O]2·[Al8P12O48H4]/2D |

90/98 |

|

3.01×10-3 |

0.20 |

[156] |

|

(C4H7N2)(C3H4N2)2·Al3(PO4)4·0.5H2O/2D |

85/98 |

|

5.94×10-3 |

0.20 |

[164] |

|

In(HPO4)(H2PO4)(D,L-C3H7NO2)/3D |

85/98 |

|

2.9 × 10-3 |

0.19 |

[16] |

|

(NH3(CH2)3NH3)2[Fe4(OH)3(HPO4)2(PO4)3]· 4H2O/1D |

40/99 |

|

5.0 × 10-2 |

--- |

[170] |

Hbim = benzimidazole; Im =imidazole; BTA = 1,2,3-benzotriazole.

(MP2O7;For Mthe = Sn, Ce, Ti, Zr), in particular tin(IVseries of isostructural imidazole cation (ImH2)-templated derivatives, combilayered metal phosphates, [ImH2][X-(HPO4)2(H2O)2] (FJU−25-X, X = Al, Ga, and Fe high thermal sta), it was found that the proton conductivity was dependent on mobility (T ³ 400 °C) with of imidazole guests, FJU−25-Fe exhibiting the highest proton conductivities ofy (5.21 × 10−3–10−24 S·cm−1 in athe temperature range of 10 90 °C). The determined activation energies (~0.20–300 eV) °C,were under anhydrous or low humidity conditions [79][80][81][82][83]indicative of a Grotthuss-type mechanism of proton conduction.

The amino acid-template indium phosphate, In(HPO4)(H2PO4)(D,L-C3H7NO2) (SCU−12), represents a sigin of thisngular example of 3D metal phosphate-based proton conductiviors [16].

Its cry was initially explained because of protons being incorporated into the framework, formed by metal(IV) octahedra and corner-sharingstal structure is formed by edge-sharing four-ring ladders, with the amino acid molecules attached to the ladders through In–O bonds. Further bridging the indium phosphate tetrahedral, afteladders by the H2PO4- groups interaction with water vapor.

Dgives rise to a threfect sites, such as electron holes-dimensional structure. The presence of two kinds of proton carriers, [84]H2PO4- ions and zwitterioxygen vacancies are believed to favournic alanine molecules, favours the development of high proton generconductivities (2.9 × 10−3 S·cm−1 ati 85 °C and 98% RH) thronugh [85].a TGrotthesuss-type protons may-transfer mechanism (Ea = 0.19 occupyeV).

Othydrogen-bonding interstitial sites on either the M−er trivalent metal phosphates have been reported, e.g., BPO−Px [175] orand the P−CePO−P4 bonds,[176]. tThus, generating a hoppinge former exhibited a proton trconductivity of 7.9 × 10−2 S·cm−1 ans self-sport between theupported electrolyte and 4.5 × 10−2 S·cm−1 ase (PBI)−4BPOx composites [86][87]. Imembrane, support of this,measured at 150 °C and 5% 1RH, NMR studies revealed two signals correspondingbut structure/conductivity correlations were not established because of its amorphous nature. The latter showed a low-temperature (RT) proton conduction < 10−5 S·cm−1 ato hydrogen-bonded inte 100% RH through a structure-independent proton-transport mechanism [176].

There are only a few examplestitial of metal(III) pyrophosphates displaying protons at conductivity. Among them is the open framework magnesium aluminophosphate MgAlP2O7(OH)(H2O)2 (JU102) [167]. Its structuret is composed of tetrahedral Al3+ and metal octahedral Mg2+ ions coordites in In3+-dnated by pyrophosped SnP2O7hate ions. FurtThermore, indium doping seemed not to affect tis connectivity results in an open framework with unidirectional 8-ring channels. The proton conduction occurring by a hopping mechanism between octahedral and tetrahedral sitesproperties originate from the existence of an H-bond network in which coordinated water molecules participate.

Thus, the increased p proton conductivity measured at 55 °C on water-immersed samples was 3.86 × 10−4 S·cm−1 [167], which roaised to 1.19 × 10−3 S·cm−1 when calconductivity is insteined at 250 °C and measured at the same conditions, while the Ea value hard attributable to increasedly changed from 0.16 to 0.2 eV. This behaviour was explained as being due to a dehydration–rehydration process that enhances proton concentrationductivity by altering [88]. Tthe sH-bonding netrategy of dopant inserwork and the pathway of proton transfer.

Anotiher example of 3D on into the M(IVpen framework metal(III) pyrophosphate has been further extendis the compound NH4TiP2O7 [177]. Thed to include other dopant divalent and trivstructure of this solid is composed of negatively charged [TiP4O12]− lalyent metal ions, such as Mg2+rs, forming one-dimensional six-membered ring channels, Al3+,where Sb3+,the Sc3NH4+, and Gions a3+,re wilocath a maximumed. Its proton conductivity of increased from 10.195−6 S·cm−1 bundeing reporr anhydrous conditions to 10−3 S·cm−1 ated for Iull-hydration condition0.1Ss an0.9P2O7d 84 [89]°C. The Howlow Ea valuev, 0.17 er, recent studies on metal doped and undoped SnP2O7V, characteristic of a Grotthuss-type proton-transfer mechanism, was asuggested that itsociated with the role played by the NH4+ ions in co-precipitated phosphorous-rich amorphous phases where thethe channels as proton donors and promoters of proton migration. A drop in proton conductivity mostly resides, while the crystallinewas observed when the triclinic TiP2O7 phase formexhibit a very low conductivity (~10−8d by thermal decomposition of S·cm−1 atNH4TiP2O7 150−300 °C) [90177].

5. Outlook

LGreat effow crystallinity titanium pyroprts have been devoted to the synthesis and characterization of metal phosphates also exhibit high -based proton conductivityors over more than [91].three Vdecalues of 0.0019–0.0044 S·cdes. Among them, zirconium−1, phosphat 100 °C and 100% RH were reported for these compounds. The proton conduction is attributables are prominent not only because of the feasibility of Zr(IV) and phosphate ions to form a rich variety of crystallographic architectures (from 1D to 3D open frameworks) but also due to the presence of H2PO4- ir outstanding HPO42− spropecrties, demonstrated b and workability while being environmentally 31Pbenign MAS NMR and FTIR, and it occurslow cost materials.

Althrough a water-facilitated Grotthuss-type proton transport mechanism. Titanium pough the prototype layered α-zirconium phosphate has been commonly proven as a filler for PEMFCs devices, new synthetic designs of M(IV) phosphates, including pyrophosphates are also prone to be functionalized with compounds, are promising candidates to broaden their applicability in different electrochemical devices. Other M(IV) phosphonates groups. Thus, mixed titanium phosphate/phosphonates, Ti(HPO4)1.00(O3PC6H4SO3H)0.85(OH)0.30·nH2O [92]ates and pyrophosphates (M = Ti, Sn) are less known due, in part, to their amorphous nature or strong tendency to amorphise at working temperatures, though, displayed an exceptionaln some cases, these compounds presented remarkable proton conductivity ofproperties.

CsH2PO4, a 0.1super S·cprotonic m−1aterial, wat 100 °C.

s proven as Aa structurally uitable electrolyte for both H2/O2 and different proton-conductor metal pyrophosphate is the mixrect methanol fuel cells operated at ~240 °C, and provides excellent performance when controlling its thermal stability. In addition, combinations with other materials are possible to adjust the specific characteristics of the composite CsH2PO4 electrolyte, thus, offering a wid template-containie range of compositions with tuning properties.

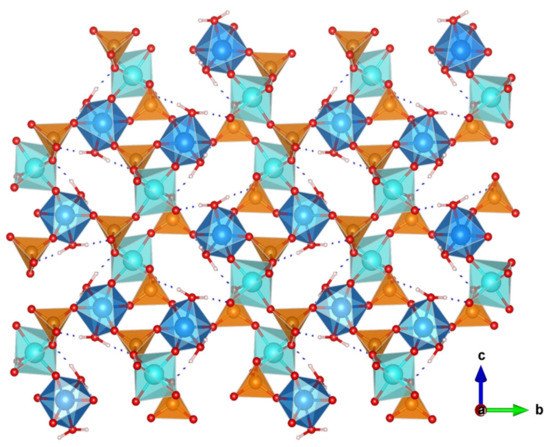

Recengtly, research vanadium nickel pyrophosphate, (C6H14N2)[Nand developments in metal phosphate proton conductors have been addressed to divalent or triV2O6H8(P2O7)2]·2H2Ovalent (Figure 9).metal Iphosphats crystales, which present a remarkable structure is composed of octahedrally coordinated V(IV) and Ni(II) interconnected throughal versatility and tunable conductivities; however, more in-depth studies are required to assess their potential use and applicability for low and intermediate temperature fuel cells.

brApplidging pyrocations of metal phosphate groups, thus creating a 3D framework of [NiV2O6H8(P2O7)2]2−s as electrolytes or as electrolyte components are in continuous progress, although their use for energy storage and conversion remains a challenge. For practical applications in funit charged-compensated by el cells at low/intermediate temperatures, phosphate-based protonated DABCO molecules. Hydrogen-bonding networks inside 3D channels facilitate the proton transport conducting electrolytes have demonstrated acceptable proton conductivity values; however, other features, such as their mechanical strength, chemical/thermal stabilities, film-forming ability (in the case of composite membranes), durability, and thus this materialfuel cross-over, are key factors to be improved.

Funding: exThibits a remarkable proton conductivity ofs research was funded by PID2019−110249RB-I00 (MICIU/AEI, Spain) and PY20−00416 (Junta de Andalucia, Spain/FEDER) research projects.

Acknowledgments: 2M.B.G.0 × 1 thanks PAIDI2020−2 S·researcm−1h grat 60 °C and 100% RH through a Grotthuss-type proton-transfer mechanism (Ea = 0nt (DOC_00272 Junta de Andalucia, Spain) and R.M.P.C. thanks University of Malaga under Plan Propio de Investigación for financial support.38 eV) [93].

References

- Shivhare, A.; Kumara, A.; Srivastava, R. Metal phosphate catalysts to upgrade ligno-cellulose biomass into value-added chemicals and biofuels. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 3818–3841.

- Zhao, H.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Insights into Transition Metal Phosphate Materials for Efficient Electrocatalysis. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 3797–3810.

- Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, D.; Wei, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y. New Versatile Synthetic Route for the Preparation of Metal Phosphate Decorated Hydrogen Evolution Photocatalysts. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 1566–1575.

- Goñi-Urtiaga, A.; Presvytes, D.; Scott, K. Solid acids as electrolyte materials for proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysis: Review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2012, 37, 3358–3372.Goñi-Urtiaga, A.; Presvytes, D.; Scott, K. Solid acids as electrolyte materials for proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrol-ysis: Review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2012, 37, 3358–3372.

- Paschos, O.; Kunze, J.; Stimming, U.; Maglia, F. A review on phosphate based, solid state, protonic conductors for intermediate temperature fuel cells. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2011, 23, 234110.Paschos, O.; Kunze, J.; Stimming, U.; Maglia, F. A review on phosphate based, solid state, protonic conductors for interme-diate temperature fuel cells. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2011, 23, 234110.

- Haile, S.M.; Chisholm, C.R.I.; Sasaki, K.; Boysen, D.A.; Uda, T. Solid acid proton conductors: From laboratory curiosities to fuel cell electrolytes. Faraday Discuss. 2007, 134, 17–39.

- Cheng, Q.; Zhao, X.; Yang, G.; Mao, L.; Liao, F.; Chen, F.; He, P.; Pan, D.; Chen, S. Recent advances of metal phosphates-based electrodes for high-performance metal ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 41, 842–882.

- Habraken, W.; Habibovic, P.; Epple, M.; Bohner, M. Calcium phosphates in biomedical applications: Materials for the future? Mater. Today 2015, 19, 69–87.Habraken, W.; Habibovic, P.; Epple, M.; Bohner, M. Calcium phosphates in biomedical applications: Materials for the fu-ture? Mater. Today 2015, 19, 69–87.

- Li, J.; Yi, M.; Zhang, L.; You, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, B. Energy related ion transports in coordination polymers. Nano Select. 2021, 1–19.Mohammad, N.; Mohamad, A.B.; Kadhum, A.A.H.; Loh, K.S. A review on synthesis and characterization of solid acid mate-rials for fuel cell applications. J. Power Sources 2016, 322, 77–92.

- Pica, M.; Donnadio, A.; Casciola, M. From microcrystalline to nanosized α-zirconium phosphate: Synthetic approaches and applications of an old material with a bright future. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 374, 218–235.

- Wong, N.E.; Ramaswamy, P.; Lee, A.S.; Gelfand, B.S.; Bladek, K.J.; Taylor, J.M.; Spasyuk, D.M.; Shimizu, G.K.H. Tuning Intrinsic and Extrinsic Proton Conduction in Metal−Organic Frameworks by the Lanthanide Contraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14676–14683.Wong, N.E.; Ramaswamy, P.; Lee, A.S.; Gelfand, B.S.; Bladek, K.J.; Taylor, J.M.; Spasyuk, D.M.; Shimizu, G.K.H. Tuning In-trinsic and Extrinsic Proton Conduction in Metal−Organic Frameworks by the Lanthanide Contraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14676–14683.

- Horike, S.; Umeyama, D.; Inukai, M.; Itakura, T.; Kitagawa, S. Coordination-network-based ionic plastic crystal for anhydrous proton conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7612–7615.Horike, S.; Umeyama, D.; Inukai, M.; Itakura, T.; Kitagawa, S. Coordination-network-based ionic plastic crystal for anhy-drous proton conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7612–7615.

- Zhang, K.-M.; Lou, Y.-L.; He, F.-Y.; Duan, H.-B.; Huang, X.-Q.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, H.-R. The water-mediated proton conductivity of a 1D open framework inorganic-organic hybrid iron phosphate and its composite membranes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, 134, 109032.

- Yu, J.-W.; Yu, H.-J.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zou, Y., Luo, H.-B.; Wang, L.; Ren, X.-M. Humidity-sensitive irreversible phase transformation of open-framework zinc phosphate and its water-assisted high proton conduction properties. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 8070–8075.Yu, J.-W.; Yu, H.-J.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zou, Y., Luo, H.-B.; Wang, L.; Ren, X.-M. Humidity-sensitive irreversible phase trans-formation of open-framework zinc phosphate and its water-assisted high proton conduction properties. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 8070–8075.

- Su, X.; Yao, Z.; Ye, Y.; Zeng, H.; Xu, G.; Wu, L.; Ma, X.; Chen, Q.-H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. 40-Fold Enhanced Intrinsic Proton Conductivity in Coordination Polymers with the Same Proton-Conducting Pathway by Tuning Metal Cation Nodes. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 983–986.

- Shi, J.; Wang, K.; Li, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, Z. Exploration of new water stable proton-conducting materials in an amino acid-templated metal phosphate system. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 654–658.Shi, J.; Wang, K.; Li, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, Z. Exploration of new water stable proton-conducting materials in an ami-no acid-templated metal phosphate system. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 654–658.

- Zhang, K.-M.; He, F.-Y.; Duan, H.-B.; Zhao, H.-R. An alkali metal ion-exchanged metal-phosphate (C2H10N2)xNa1−x[Mn2(PO4)2] with high proton conductivity of 10−2 S·cm−1. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 6639–6646.

- Zhang, K.-M.; Jia, Y.; Gu, Y., He, F.-Y.; Zhao, H.-R. A facile and efficient method to improve the proton conductivity of open framework metal phosphates under aqueous condition. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 120, 108128.

- Umeyama, D.; Horike, S.; Inukai, M.; Kitagawa, S. Integration of Intrinsic Proton Conduction and Guest-Accessible Nanospace into a Coordination Polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11345–11350.Umeyama, D.; Horike, S.; Inukai, M.; Kitagawa, S. Integration of Intrinsic Proton Conduction and Guest-Accessible Nano-space into a Coordination Polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11345–11350.

- Baranov, A.I.; Khiznichenko, V.P.; Sandler, V.A.; Shuvalov, L.A. Frequency dielectric dispersion in the ferroelectric and superionic phases of CsH2PO4. Ferroelectrics 1988, 81, 183–186.

- Colomban, P. Chemistry of Solid-State Materials. In Proton Conductors: Solid, Membranes and Gels-Materials and Devices; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992.Colomban, P. Chemistry of Solid-State Materials. In Proton Conductors: Solid, Membranes and Gels-Materials and Devices; Cam-bridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992.

- Fragua, D.M.; Castillo, J.; Castillo, R.; Vargas, R.A. New amorphous phase KnH2PnO3n+1(n>>1) in KH2PO4. Rev. Latin Am. Metal. Mat. 2009, 2, 491–497.

- Botez, C.E.; Tackett, R.J.; Hermosillo, J.D.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L. High pressure synchrotron x-ray diffraction studies of superprotonic transitions in phosphate solid acids. Solid State Ion. 2012, 213, 58–62.Skou, E.; Andersen, I.G.K.; Simonsen, K.E.; Andersen, E.K. Is UO2HPO4·4H2O a proton conductor? Solid State Ion. 1983, 9, 1041–1047.

- Baranov, A.I. Crystals with disordered hydrogen-bond networks and superprotonic conductivity. Review. Crystallogr. Rep. 2003, 48, 1012–1037.Cabeza, A.; Martinez, M.; Benavente, J.; Bruque, S. Current rectification by H3OUO2PO4 3H2O (HUP) thin films in electrolyte media. Solid State Ion. 1992, 51, 127–131.

- Bagryantseva, I.N.; Gaydamaka, A.A.; Ponomareva, V.G. Intermediate temperature proton electrolytes based on cesium dihydrogen phosphate and Butyral polymer. Ionics 2020, 26, 1813–1818.Barboux, P.; Morineau, R.; Livage, J. Protonic conductivity in hydrates. Solid State Ion. 1988, 27, 221–225.

- Dreßler, C.; Sebastiani, D. Effect of anion reorientation on proton mobility in the solid acids family CsHyXO4 (X = S, P, Se, y = 1, 2) from ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 10738–10752.Barboux, P.; Livage, J. Ionic conductivity in fibrous Ce(HPO4)2·(3+x)H2O. Solid State Ion. 1989, 34, 47–52.

- Taninouchi, Y.K.; Uda, T.; Awakura, Y.; Ikeda, A.; Haile, S.M. Dehydration behavior of the superprotonic conductor CsH2PO4 at moderate temperatures: 230 to 260 °C. J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 3182–3189.Li, J.; Yi, M.; Zhang, L.; You, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, B. Energy related ion transports in coordination polymers. Nano Select. 2021, 1–19.

- Mathur, L.; Kim, I.-H.; Bhardwaj, A.; Singh, B.; Park, J.-Y.; Song, S.-J. Structural and electrical properties of novel phosphate based composite electrolyte for low-temperature fuel cells. Composites Part B 2020, 202, 108405.Steele, B.C.H.; Heinzel, A. Materials for fuel-cell technologies. Nature 2001, 414, 345–352.

- Otomo, J.; Tamaki, T.; Nishida, S.; Wang, S.; Ogura, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Wen, C.-J.; Nagamoto, H.; Takahashi, H. Effect of water vapor on proton conduction of cesium dihydrogen phosphate and application to intermediate temperature fuel cells. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2005, 35, 865–870.Wei, J. Proton-Conducting Materials Used as Polymer Electrolyte Membranes in Fuel Cells (ch 9). In Polymer-Based Multi-functional Nanocomposites and Their Applications; Song, K., Liu, C., Guo, J.Z., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Chapter 9, pp. 245–260.

- Uda, T.; Haile, S.M. Thin-membrane solid-acid fuel cell. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2005, 8, A245–A246.Sazali, N.; Salleh, W.N.W.; Jamaludin, A.S.; Razali, M.N.M. New Perspectives on Fuel Cell Technology: A Brief Review. Membranes 2020, 10, 99.

- Navarrete, L.; Andrio, A.; Escolástico, S.; Moya, S.; Compañ, V.; Serra, J.M. Protonic Conduction of Partially-Substituted CsH2PO4 and the Applicability in Electrochemical Devices. Membranes 2019, 9, 49.Dupuis, A.-C. Proton exchange membranes for fuel cells operated at medium temperatures: Materials and experimental techniques. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2011, 56, 289–327.

- Ponomareva, V.G.; Bagryantseva, I.N.; Gaydamaka, A.A. Study of the Phase Composition and Electrotransport Properties of the Systems Based on Mono- and Disubstituted Phosphates of Cesium and Rubidium. Chem. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 238–245.Peighambardoust, S.J.; Rowshanzamir, S.; Amjadi, M. Review of the proton exchange membranes for fuel cell applications. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 9349–9384.

- Martsinkevich, V.V.; Ponomareva, V.G. Double salts Cs1-xMxH2PO4 (M = Na, K, Rb) as proton conductors. Solid State Ion. 2012, 225, 236–240.Mauritz, K.A.; Moore, R.B. State of understanding of Nafion. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4535–4585.

- Ponomareva, V.G.; Bagryantseva, I.N. Superprotonic CsH2PO4-CsHSO4 solid solutions. Inorg. Mater. 2012, 48, 187–194.Hickner, M.A.; Ghassemi, H.; Kim, Y.S.; Einsla, B.R.; McGrath, J.E. Alternative polymer systems for proton exchange mem-branes (PEMs). Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4587–4612.

- Ponomareva, V.G.; Uvarov, N.F.; Lavrova, G.V.; Hairetdinov, E.F. Composite protonic solid electrolytes in the CsHSO4-SiO2 system. Solid State Ion. 1996, 90, 161–166.Han, X.; Xie, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Pang, J.; Jiang, Z. Synthesis and properties of novel poly(arylene ether)s with densely sulfonated units based on carbazole derivative. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 589, 117230.

- Ponomareva, V.G.; Shutova, E.S.; Matvienko, A.A. Conductivity of Proton Electrolytes Based on Cesium Hydrogen Sulfate Phosphate. Inorg. Mater. 2004, 40, 721–728.Kuzmenko, M.; Poryadchenko, N. Perspective materials for application in fuel-cell technologies. In Fuel Cell Technologies: State and Perspectives; Sammes. N., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 253–258.

- Otomo, J.; Minagawa, N.; Wen, C.-J.; Eguchi, K.; Takahashi, H. Protonic conduction of CsH2PO4 and its composite with silica in dry and humid atmospheres. Solid State Ion. 2003, 156, 357–369.Lee, K.-S.; Maurya, S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kreller, C.R.; Wilson, M.S.; Larsen, D.; Elangovan, S.E.; Mukundan, R. Intermediate temper-ature fuel cells via an ion-pair coordinated polymer electrolyte. Energy Env. Sci. 2018, 11, 979–987.

- Ponomareva, V.G.; Shutova, E.S. High-temperature behavior of CsH2PO4 and CsH2PO4-SiO2 composites. Solid State Ion. 2007, 178, 729–734.Norby, T. Solid-state protonic conductors: Principles, properties, progress and prospects. Solid State Ion. 1999, 125, 1–11.

- Singh, D.; Singh, J.; Kumar, P.; Veer, D.; Kumar, D.; Katiyar, R.S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A. The Influence of TiO2 on the Proton Conduction and Thermal Stability of CsH2PO4 Composite Electrolytes. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 37, 227–236.Li, Q.; He, R.; Jensen, J.O.; Bjerrum, N.J. Approaches and Recent Development of Polymer Electrolyte Membranes for Fuel Cells Operating above 100 °C. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 4896–4915.

- Singh, D.; Kumar, P.; Singh, J.; Veer, D.; Kumar, A.; Katiyar, R.S. Structural, thermal and electrical properties of composites electrolytes (1−x) CsH2PO4/x ZrO2 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.4) for fuel cell with advanced electrode. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 46.Loreti, G.; Facci, A.L.; Ubertini, S. High-Efficiency Combined Heat and Power through a High-Temperature Polymer Elec-trolyte Membrane Fuel Cell and Gas Turbine Hybrid System. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12515.

- Veer, D.; Kumar, P.; Singh, D.; Kumar, D.; Katiyar, R.S. A synergistic approach to achieving high conduction and stability of CsH2PO4/NaH2PO4/ZrO2 composites for fuel cells. Mater. Adv. 2021, 3, 409–417.Boysen, D.A.; Uda, T.; Chisholm, C.R.I.; Haile, S.M. High-Performance Solid Acid Fuel Cells Through Humidity Stabiliza-tion. Science 2004, 303, 68–70.

- Aili, D.; Gao, Y.; Han, J.; Li, Q. Acid-base chemistry and proton conductivity of CsHSO4, CsH2PO4 and their mixtures with N-heterocycles. Solid State Ion. 2017, 306, 13–19.Zhang, J.; Aili, D.; Lu, S.; Li, Q.; Jiang, S.P. Advancement toward Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells at Elevated Temperatures. AAAS Res. 2020, 2020, 9089405.

- Bagryantseva, I.N.; Ponomareva, V.G.; Khusnutdinov, V.R. Intermediate temperature proton electrolytes based on cesium dihydrogen phosphate and poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene). J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 14196–14206.Clearfield, A.; Smith, S.D. The crystal structure of zirconium phosphate and the mechanism of its ion exchange behavior. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1968, 28, 325–330.

- Ponomareva, V.G.; Bagryantseva, I.N.; Shutova, E.S. Hybrid systems based on nanodiamond and cesium dihydrogen phosphate. Mater. Today 2020, 25, 521–524.Clearfield, A.; Smith, G.D. Crystallography and structure of alpha-zirconium bis(monohydrogen orthophosphate) mono-hydrate. Inorg. Chem. 1969, 8, 431–436.

- Ma, N.; Kosasang, S.; Yoshida, A.; Horike, S. Proton-conductive coordination polymer glass for solid-state anhydrous proton batteries. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 5818–5824.Troup, J.M.; Clearfield, A. Mechanism of ion exchange in zirconium phosphates. 20. Refinement of the crystal structure of .alpha.-zirconium phosphate. Inorg. Chem. 1977, 16, 3311–3314.

- Zhao, H.-R.; Xue, C.; Li, C.-P.; Zhang, K.-M.; Luo, H.-B.; Liu, S.-X.; Ren, X.-M. A Two-Dimensional inorganic−organic hybrid solid of manganese(II) hydrogenophosphate showing high proton conductivity at room temperature. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 8971–8975.Casciola, M. From layered zirconium phosphates and phosphonates to nanofillers for ionomeric membranes. Solid State Ion. 2019, 336, 1–10.

- Wang, M.; Luo, H.-B.; Liu, S.-X.; Zou, Y.; Tian, Z.-F.; Li, L.; Liu, J.-L.; Ren, X.-M. Water assisted high proton conductance in a highly thermally stable and superior water-stable open-framework cobalt phosphate. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 19466–19472.Ogawa, T.; Ushiyam, H.; Lee, J.-M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Yamashita, K. Theoretical Studies on Proton Transfer among a High Density of Acid Groups: Surface of Zirconium Phosphate with Adsorbed Water Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 5599–5606.

- Umeyama, D.; Horike, S.; Inukai, M.; Itakura, T.; Kitagawa, S. Inherent Proton Conduction in a 2D Coordination Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12780–12785.Alberti, G.; Casciola, M.; Costantino, U. Inorganic ion-exchange pellicles obtained by delamination of α-zirconium phos-phate crystals. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1985, 107, 256–263.

- Inukai, M.; Horike, S.; Chen, W.; Umeyama, D.; Itakurad, T.; Kitagawa, S. Template-directed proton conduction pathways in a coordination framework. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014, 2, 10404–10409.Alberti, G.; Casciola, M.; Costantino, U.; Leonardi, M. AC conductivity of anhydrous pellicular zirconium phosphate in hydrogen form. Solid State Ion. 1984, 14, 289–295.

- Zhao, H.R.; Jia, Y.; Gu, V.; He, F.Y.; Zhang, K.M.; Tian, Z.F.; Liu, J.L. A 3D open-framework iron hydrogenophosphate showing high proton conductance under water and aqua-ammonia vapor. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 9046–9051.Casciola, M.; Costantino, U.; D’Amico, S. Protonic conduction of intercolation compounds of α-zirconium phosphate with propylamine. Solid State Ion. 1986, 22, 127–133.

- Zima, V.; Lii, K.-H. Synthesis and characterization of a novel one-dimensional iron phosphate: [C4H12N2]1.5[Fe2(OH)(H2PO4)(HPO4)2(PO4)]·0.5H2O. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1998, 24, 4109–4112.Alberti, G.; Casciola, M.; Cavalaglio, S.; Vivani, R. Proton conductivity of mesoporous zirconium phosphate pyrophos-phate. Solid State Ion. 1999, 125, 91–97.

- Lii, K.-H.; Huang, Y.-F. Large tunnels in the hydrothermally synthesized open-framework iron phosphate (NH3(CH2)3NH3)2[Fe4(OH)3(HPO4)2(PO4)3]·xH2O. Chem. Commun. 1997, 9, 839–840.Alberti, G.; Casciola, M.; Donnadio, A.; Piaggio, P.; Pica, M.; Sisani, M. Preparation and characterisation of α-layered zirco-nium phosphate sulfophenylenphosphonates with variable concentration of sulfonic groups. Solid State Ion. 2005, 176, 2893–2898.

- Bazaga-García, M.; Colodrero, R.M.P.; Papadaki, M.; Garczarek, P.; Zon, J.; Olivera-Pastor, P.; Losilla, E.R.; Reina, L.L.; Aranda, M.A.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; et al. Guest Molecule-Responsive Functional Calcium Phosphonate Frameworks for Tuned Proton Conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5731–5739.Gui, D.; Zheng, T.; Xie, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Diwu, J.; Chai, Z.; Wang, S. Significantly dense two-dimensional hy-drogen-bond network in a layered zirconium phosphate leading to high proton conductivities in both water-assisted low-temperature and anhydrous intermediate-temperature regions. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 12508–12511.

- Lim, D.-W.; Kitagawa, H. Proton Transport in Metal−Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8416–8467.Yu, J.-W.; Yu, H.-J.; Yao, Z.-Y.; Li, Z.-H.; Ren, Q.; Luo, H.-B.; Zou, Y.; Wang, L.; Ren, X.-M. A water-stable open-framework zirconium(IV) phosphate and its water-assisted high proton conductivity. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 6093–6097.

- Mamlouk, M.; Scott, K. A boron phosphate-phosphoric acid composite membrane for medium temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2015, 286, 290–298.Gui, D.; Dai, X.; Tao, Z.; Zheng, T.; Wang, X.; Silver, M.A.; Shu, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; et al. Unique proton trans-portation pathway in a robust inorganic coordination polymer leading to intrinsically high and sustainable anhydrous proton conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6146–6155.

- Pusztai, P.; Haspel, H.; Tóth, I.Y.; Tombácz, E.; László, K.; Kukovecz, Á.; Kónya, Z. Structure-Independent Proton Transport in Cerium(III) Phosphate Nanowires. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 9947–9956.Kusoglu, A.; Weber, A.Z. New Insights into Perfluorinated Sulfonic-Acid Ionomers. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 987–1104.

- Mu, Y.; Wang, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.Y.; Yu, J.H. Organotemplate-free synthesis of an open-framework magnesium aluminophosphate with proton conduction properties. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 2149–2151.Alberti, G.; Casciola, M.; Capitani, D.; Donnadio, A.; Narducci, R.; Pica, M.; Sganappa, M. Novel Nafion–zirconium phos-phate nanocomposite membranes with enhanced stability of proton conductivity at medium temperature and high relative humidity. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 52, 8125–8132.

- Petersen, H.; Stefmann, N.; Fischer, M.; Zibrowius, I.R.; Philippi, W.; Schmidt, W.; Weidenthaler, C. Crystal structures of two titanium phosphate-based proton conductors: Ab initio structure solution and materials properties. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 2379–2390.Grot, W.G.; Rajendran, G.; Hendrickson, J.S. International Patent Application No. PCT/US96/03804, International Publication No. WO 96/2975, 26, September, 1996.

- Clearfield, A.; Smith, S.D. The crystal structure of zirconium phosphate and the mechanism of its ion exchange behavior. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1968, 28, 325–330.Alberti, G.; Casciola, M.; Pica, M.; Tarpanelli, T.; Sganappa, M. New Preparation Methods for Composite Membranes for Medium Temperature Fuel Cells Based on Precursor Solutions of Insoluble Inorganic Compounds. Fuel Cells 2005, 5, 366–374.

- Clearfield, A.; Smith, G.D. Crystallography and structure of alpha-zirconium bis(monohydrogen orthophosphate) monohydrate. Inorg. Chem. 1969, 8, 431–436.Casciola, M.; Bagnasco, G.; Donnadio, A.; Micoli, L.; Pica, M.; Sganappa, M.; Turco, M. Conductivity and Methanol Permea-bility of Nafion–Zirconium Phosphate Composite Membranes Containing High Aspect Ratio Filler Particles. Fuel Cells 2009, 9, 394–400.

- Troup, J.M.; Clearfield, A. Mechanism of ion exchange in zirconium phosphates. 20. Refinement of the crystal structure of .alpha.-zirconium phosphate. Inorg. Chem. 1977, 16, 3311–3314.Arbizzani, C.; Donnadio, A.; Pica, M.; Sganappa, M.; Varzi, A.; Casciola, M.; Mastragostino, M. Methanol permeability and performance of Nafion–zirconium phosphate composite membranes in active and passive direct methanol fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 7751–7756.

- Casciola, M. From layered zirconium phosphates and phosphonates to nanofillers for ionomeric membranes. Solid State Ion. 2019, 336, 1–10.Pica, M.; Donnadio, A.; Casciola, M.; Cojocaru, P.; Merlo, L. Short side chain perfluorosulfonic acid membranes and their composites with nanosized zirconium phosphate: Hydration, mechanical properties and proton conductivity. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 24902–24908.

- Gui, D.; Zheng, T.; Xie, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Diwu, J.; Chai, Z.; Wang, S. Significantly dense two-dimensional hydrogen-bond network in a layered zirconium phosphate leading to high proton conductivities in both water-assisted low-temperature and anhydrous intermediate-temperature regions. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 12508–12511.Pica, M.; Donnadio, A.; Capitani, D.; Vivani, R.; Troni, E.; Casciola, M. Advances in the Chemistry of Nanosized Zirconium Phosphates: A New Mild and Quick Route to the Synthesis of Nanocrystals. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 11623–11630.

- Yu, J.-W.; Yu, H.-J.; Yao, Z.-Y.; Li, Z.-H.; Ren, Q.; Luo, H.-B.; Zou, Y.; Wang, L.; Ren, X.-M. A water-stable open-framework zirconium(IV) phosphate and its water-assisted high proton conductivity. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 6093–6097.Bauer, F.; Willert-Porada, M. Comparison between Nafion and a Nafion zirconium phosphate nanocomposite in fuel cell applications. Fuel Cells 2006, 6, 261–269.

- Gui, D.; Dai, X.; Tao, Z.; Zheng, T.; Wang, X.; Silver, M.A.; Shu, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; et al. Unique proton transportation pathway in a robust inorganic coordination polymer leading to intrinsically high and sustainable anhydrous proton conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6146–6155.Casciola, M.; Cojocaru, P.; Donnadio, A., Giancola, S.; Merlo, L.; Nedellec, Y.; Pica, M.; Subianto, S. Zirconium phosphate reinforced short side chain perflurosulfonic acid membranes for medium temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cell application. J. Power Sources 2014, 262, 407–413.

- Alberti, G.; Cardini-Galli, P.; Costantino, U.; Torracca, E. Crystalline insoluble salts of polybasic metals—I Ion-exchange properties of crystalline titanium phosphate. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1967, 29, 571–578.Yang, C.; Srinivasan, S.; Aricò, A.S.; Creti, P.; Baglio, V.; Antonucci, V. Composition Nafion/zirconium phosphate mem-branes for direct methanol fuel cell operation at high temperature. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2001, 4, A31–A34.

- Christensen, A.N.; Anderson, E.K.; Andersen, I.G.; Alberti, G.; Nielsen, M.; Lehmann, E.K. X-Ray Powder diffraction study of layer compounds. The crystal structure of α-Ti (HPO4)2·H2O and a proposed structure for γ-Ti (H2PO4)(PO4)·2H2O. Acta Chem. Scand. 1990, 44, 865–872.Yang, C.; Costamagna, P.; Srinivasan, S.; Benziger, J.; Bocarsly, A.B. Approaches and technical challenges to high tempera-ture operation of proton exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2001, 103, 1–9.

- Li, Y.J.; Whittingham, M.S. Hydrothermal synthesis of new metastable phases: Preparation and intercalation of a new layered titanium phosphate. Solid State Ion. 1993, 63, 391–395.Costamagna, P.; Yang, C.; Bocarsly, A.B.; Srinivasan, S. Nafion (R) 115/zirconium phosphate composite membranes for op-eration of PEMFCs above 100 °C. Electrochim. Acta 2002, 47, 1023–1033.

- Kőrösi, L.; Papp, S.; Dékány, I. A layered titanium phosphate Ti2O3(H2PO4)2·2H2O with rectangular morphology: Synthesis, structure, and cysteamine intercalation. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 4356–4363.Yang, C.; Srinivasan, S.; Bocarsly, A.B.; Tulyani, S.; Benziger, J.B. A comparison of physical properties and fuel cell perfor-mance of Nafion and zirconium phosphate/Nafion composite membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2004, 237, 145–161.

- Ekambaram, S.; Serre, C.; Férey, G.; Sevov, S.C. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of an ethylenediamine-templatedmixed-valence titanium phosphate. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 444–449.Lee, H.-K.; Kim, J.-I.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, T.-H. A study on self-humidifying PEMFC using Pt-ZrP-Nafion composite membrane. Electrochim. Acta 2004, 50, 761–768.

- Krogh Andersen, A.M.; Norby, P.; Hanson, J.C.; Vogt, T. Preparation and characterization of a new 3-dimensional zirconium hydrogen phosphate, τ-Zr(HPO4)2. Determination of the complete crystal structure combining synchrotron X-ray single-crystal diffraction and neutron powder diffraction. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 876–881.Escorihuela, J.; Narducci, R.; Compañ, V.; Costantino, F. Proton Conductivity of Composite Polyelectrolyte Membranes with Metal-Organic Frameworks for Fuel Cell Applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1801146.

- Bortun, A.I.; Khainakov, S.A.; Bortun, L.N.; Poojary, D.M.; Rodriguez, J.; Jose, R. Garcia, J.R.; Clearfield, A. Synthesis and characterization of two novel fibrous titanium phosphates Ti2O(PO4)2·2H2O. Chem. Mater. 1997, 9, 1805–1811.Liu, K.L.; Lee, H.C.; Wang, B.Y.; Lue, S.J.; Lu, C.Y.; Tsai, L.D.; Fang, J.; Chao, C.Y. Sulfonated poly(styrene-block-(ethylene-ran-butylene)-block-styrene (SSEBS)-zirconium phosphate) (ZrP) composite membranes for direct methanol fuel cells. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 495, 110–120.

- Salvadó, M.A.; Pertierra, P.; García-Granda, S.; García, J.R.; Fernández-Diaz, M.T.; Dooryhee, E. Crystal structure, including H-atom positions, of Ti2O(PO4)2·(H2O)2 determined from synchrotron X-ray and neutron powder data. Eur. J. Solid State Inorg. Chem. 1997, 34, 1237–1247.Hu, H.; Ding, F.; Ding, H.; Liu, J.; Xiao, M.; Meng, Y.; Sun, L. Sulfonated poly(fluorenyl ether ketone)/Sulfonated α-zirconium phosphate Nanocomposite membranes for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2020, 3, 498–507.

- Babaryk, A.A.; Adawy, A.; García, I. Trobajo, C.; Amghouz, Z.; Colodrero, R.M.P. Cabeza, A.; Olivera-Pastor, P.; Bazaga-García, M.; dos Santos-Gómez, L. Structural and proton conductivity studies of fibrous π-Ti2O(PO4)2·2H2O: Application in chitosan-based composite membranes. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 7667–7677.Pandey, J.; Seepana, M.M.; Shukla, A. Zirconium phosphate based proton conducting membrane for DMFC application. Int. J. Hydrog. 2015, 40, 9410–9421.

- Bruque, S.; Aranda, M.A.G.; R. Losilla, E.; Olivera-Pastor, P.; Maireles-Torres, P. Synthesis optimization and crystal structures of layered metal(IV) hydrogen phosphates, .alpha.-M(HPO4)2.cntdot.H2O (M = Ti, Sn, Pb). Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 893–899.He, R.; Li, Q.; Xiao, G.; Bjerrum, N.J. Proton conductivity of phosphoric acid doped polybenzimidazole and its composites with inorganic proton conductors. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 226, 169–184.

- Huang, W.; Komarneni, S.; Noh,Y.D.; Ma, J.; Chen, K.; Xue, D.; Xuea, X.; Jiang, B. Novel inorganic tin phosphate gel: Multifunctional material. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2682–2685.Gouda, M.H.; Tamer, T.M.; Konsowa, A.H.; Farag, H.A.; Mohy Eldin, M.S. Organic-Inorganic Novel Green Cation Exchange Membranes for Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. Energies 2021, 14, 4686.

- Zhang, J.; Aili, D.; Lu, S.; Li, Q.; Jiang, S.P. Advancement toward Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells at Elevated Temperatures. AAAS Res. 2020, 2020, 9089405.Alberti, G.; Cardini-Galli, P.; Costantino, U.; Torracca, E. Crystalline insoluble salts of polybasic metals—I Ion-exchange properties of crystalline titanium phosphate. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1967, 29, 571–578.

- Ansari, Y.; Telpriore, G.; Tucker, C.; Angell, A. A novel, easily synthesized, anhydrous derivative of phosphoric acid for use in electrolyte with phosphoric acid-based fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2013, 237, 47–51.Christensen, A.N.; Anderson, E.K.; Andersen, I.G.; Alberti, G.; Nielsen, M.; Lehmann, E.K. X-Ray Powder diffraction study of layer compounds. The crystal structure of α-Ti (HPO4)2·H2O and a proposed structure for γ-Ti (H2PO4)(PO4)·2H2O. Acta Chem. Scand. 1990, 44, 865–872.

- Sato, Y.; Shen, Y.; Nishida, M.; Kanematsu, W.; Hibino, T. Proton Conduction in Non-Doped and Acceptor-Doped Metal Pyrophosphate (MP2O7) Composite Ceramics at Intermediate Temperatures. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 3973–3981.Li, Y.J.; Whittingham, M.S. Hydrothermal synthesis of new metastable phases: Preparation and intercalation of a new lay-ered titanium phosphate. Solid State Ion. 1993, 63, 391–395.

- Singh, B.; Kima, J.-H.; Park, J.-Y.; Song, S.-J. Dense composite electrolytes of Gd3+-doped cerium phosphates for low-temperature proton-conducting ceramic-electrolyte fuel cells. Ceram. Inter. 2015, 41, 4814–4821.Kőrösi, L.; Papp, S.; Dékány, I. A layered titanium phosphate Ti2O3(H2PO4)2·2H2O with rectangular morphology: Synthesis, structure, and cysteamine intercalation. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 4356–4363.

- Nagao, M.; Kamiya, T.; Heo, P.; Tomita, A.; Hibino, T.; Sano, M. Proton conduction in In3+-doped SnP2O7 at intermediate temperatures. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, 1604–1609.Ekambaram, S.; Serre, C.; Férey, G.; Sevov, S.C. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of an ethylenedia-mine-templatedmixed-valence titanium phosphate. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 444–449.