Alpha-synucleinopathies are progressive neurodegenerative diseases that are characterized by pathological misfolding and accumulation of the protein alpha-synuclein (αsyn) in neurons, axons or glial cells in the brain, but also in other organs. The abnormal accumulation and propagation of pathogenic αsyn across the autonomic connectome is associated with progressive loss of neurons in the brain and peripheral organs, resulting in motor and non-motor symptoms. To date, no cure is available for synucleinopathies, and therapy is limited to symptomatic treatment of motor and non-motor symptoms upon diagnosis. Recent advances using passive immunization that target different αsyn structures show great potential to block disease progression in rodent studies of synucleinopathies. However, passive immunotherapy in clinical trials has been proven safe but less effective than in preclinical conditions. Here we review current achievements of passive immunotherapy in animal models of synucleinopathies, and we propose new research strategies to increase translational outcome in patient studies.

- alpha-synuclein

- passive immunization

- disease stratification

1. Introduction

2. C-Terminal Targeting Approaches

3. N-Terminal and NAC Targeting Approaches

4. Conformational Targeting Approaches

5. Passive Candidates Translated into Clinical Trials

| Target (αsyn) | Name | Companies | Antibody/Clone | Binding Site (aa) | Clinical Groups | Current Clinical Phase | Clinical Trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggre. | PRX002/(Prasinezumab)–PASADENA study | Hoffman-La Roche; Prothena Biosciences Limited. |

Humanized IgG1 mab version of murine 9E4 | Preferable aggregated αsyn within the C-terminal at aa 118–126 (VDPDNEAYE) |

PD patients (H&Y < 2) | Phase II; active; recruitment completed. |

NCT03100149 |

| Aggre. (Oligo/proto-fibrils) | ABBV-0805 | AbbVie; BioArctic Neuroscience AB | Humanized mAB47 mab | Preferable aggregated αsyn within the C-terminal at aa 121–127 (DNEAYEM) | PD patients (<5 years from diagnosis and H&Y < 3) | Phase I; recruiting. | NCT04127695 |

| Aggre. | MEDI1341 | Astra Zeneca; Takeda Pharmaceuticals |

Humanized IgG1 mab | Preferable aggregated αsyn within the C-terminal (within the aa 103–129 region) | Healthy individuals (MEDI1341 vs. placebo) | Phase I; recruitment completed. | NCT03272165 |

| Aggre. | BIIB054 (Cinpanemab)–SPARK study | Biogen; Neuroimmune | Healthy human memory B cells derived mab | Preferable aggregated αsyn, oxidized at N-terminal aa: 4–10 (FMKGLSK) | PD patients (<3 years from diagnosis and H&Y < 2.5) | Phase II; Terminated |

NCT03318523 |

| Aggre. | Lu AF82422–AMULET study | H. Lundbeck A/S; Genmab A/S |

Humanized IgG1 mab | Preferable aggregated αsyn within the C-terminal at aa 112–117 (ILEDMP) | MSA-P and MSA-C patients (<5 years from diagnosis, UMSARS ≤ 16, MoCA ≥ 22) | Phase II; recruiting | NCT05104476 |

6. Towards Personalized Immunotherapy

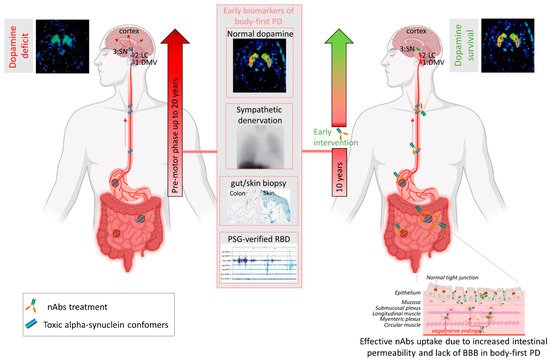

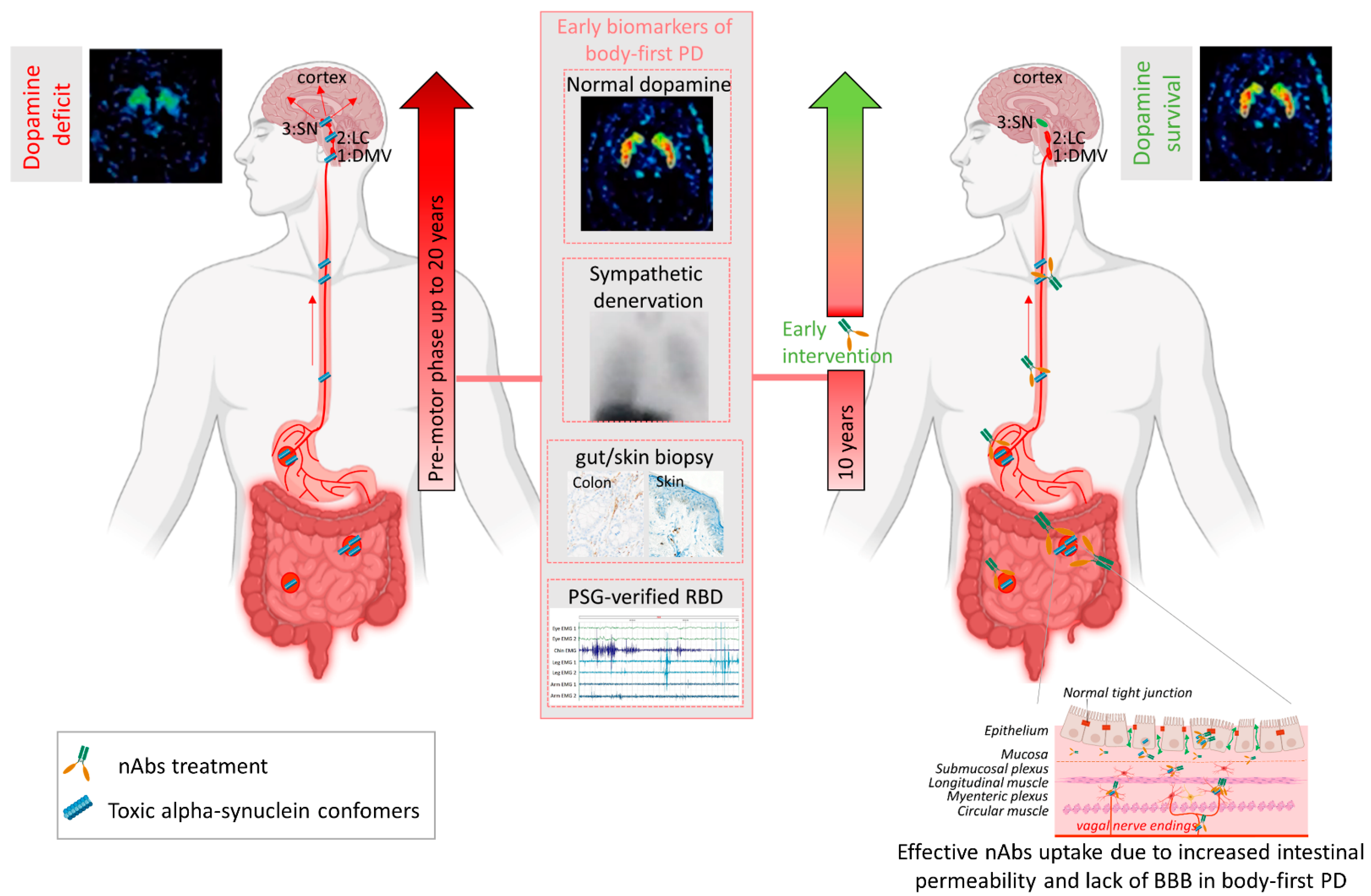

Several mechanisms have been implicated to trigger the initiation of pathogenic αsyn in the gut. Besides regulating the uptake of nutrients and water, the gut also provides an essential barrier against harmful or toxic substances from the external environment entering the body. About 400 m2 of gut internal membranes are exposed to environmental factors, compared to ~2 m2 of total skin surface area, meaning the gut is the main organ protecting against exposure to foreign pathogens [46]. It has been shown that bacterial and environmental toxins that enter the gut lumen can cause disruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier [47], alter the gut microbiome [48] and cause mucosal inflammation and oxidative stress [49][50]. A complex interplay of these factors are then able to trigger αsyn misfolding in the gut plexi, and an increased permeability of the intestinal barrier or ‘leaky gut’ will ultimately provide a route of transmission for the gut-formed αsyn seeds to the brain [51]. These findings indicate the gut as an important target for passive immunization therapy for two reasons. Early intervention in prodromal disease stages of gut-first cases may halt formation of pathogenic αsyn and subsequent gut-to-brain propagation. Second, only 0.1–0.2% of nAbs cross the blood–brain barrier. Therefore, it is conceivable that immunotherapy in prodromal patients with ‘leaky gut’ could be more effective. Increased gut permeability in prodromal patients with leaky gut might yield a better uptake of the administered nAbs near the source of pathogenic αsyn, resulting in a better treatment efficacy, as opposed to brain-first cases where the source is located in the brain (see Figure 1). Body-first PD patients are characterized by a more rapidly progressing phenotype, with faster motor and non-motor progression and more rapid cognitive decline, compared to brain-first PD patients [15][52]. This might explain why patients with fast progressive and severe symptoms benefited most from the treatment with Prasinezumab in the clinical trial. The validity of the SOC model requires further investigation, esp. in the prodromal phase. Detailed phenotyping of non-iRBD prodromal (i.e., brain-first subtype) patients is not yet available. Therefore, fundamental questions remain to be addressed: how these subtypes differ in their disease initiation mechanisms and progression patterns (esp. in the prodromal phase), and how such knowledge could be exploited for tailored subtype-specific immunotherapy. Future animal models should take into account varying disease onset sites to obtain causal and mechanistic understanding of the body-brain link in different disease subtypes, and to discover subtype-specific targets for immunotherapy. Recently developed, more sensitive, investigative tools such as PMCA (Protein-Misfolding Cyclic Amplification), RT-QuIC (Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion), PLA (Proximity Ligation Assay) and thiophene-based assays should be included while studying synucleinopathies to investigate the relation between disease onset site and subtype-specific strain characteristics. The identification of subtype-specific αsyn aggregates in easily accessible peripheral fluids or tissues from brain-first or body-first cases may enable early stratification as well as development of subtype-specific nAbs for immunotherapy.

Figure 2. Passive immunization of pre-motor body-first PD patients enhances dopamine survival. Patients with probable prodromal body-first PD could be identified by a combination of several early biomarkers, such as the presence of pathological alpha-synuclein (αsyn) in skin and/or gut biopsies, polysomnography-verified RBD, cardiac sympathetic denervation on MIBG scintigraphies, but normal or near-normal nigrostriatal dopaminergic innervation on DaT SPECT. Such detailed phenotyping in the pre-motor phase might reveal body-first PD, allowing early intervention and optimal patient selection for clinical trials. Pre-motor start of nAbs treatment increases treatment efficacy by delaying or blocking peripheral-to-brain propagation of pathology, before any irreversible damage to the dopamine system is done, hereby enhancing the probability of dopamine survival in body-first PD. Furthermore, increased gut permeability in prodromal body-first PD patients with ‘leaky gut’ or increased intestinal permeability might yield a better uptake of the administered nAbs near the source of pathogenic αsyn conformers, resulting in a better treatment efficacy, as opposed to brain-first cases where the source is located in the brain and only 0.1–0.2% of nAbs cross the blood–brain barrier. Abbreviations: nAbs: naturally occurring autoantibodies; DMV: dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; LC: locus coeruleus; SN: substantia nigra, PAF: pure autonomic failure, PSG: polysomnography, BBB: blood brain barrier. Created using Biorender.com (accessed on 30 November 2021).

Figure 2. Passive immunization of pre-motor body-first PD patients enhances dopamine survival. Patients with probable prodromal body-first PD could be identified by a combination of several early biomarkers, such as the presence of pathological alpha-synuclein (αsyn) in skin and/or gut biopsies, polysomnography-verified RBD, cardiac sympathetic denervation on MIBG scintigraphies, but normal or near-normal nigrostriatal dopaminergic innervation on DaT SPECT. Such detailed phenotyping in the pre-motor phase might reveal body-first PD, allowing early intervention and optimal patient selection for clinical trials. Pre-motor start of nAbs treatment increases treatment efficacy by delaying or blocking peripheral-to-brain propagation of pathology, before any irreversible damage to the dopamine system is done, hereby enhancing the probability of dopamine survival in body-first PD. Furthermore, increased gut permeability in prodromal body-first PD patients with ‘leaky gut’ or increased intestinal permeability might yield a better uptake of the administered nAbs near the source of pathogenic αsyn conformers, resulting in a better treatment efficacy, as opposed to brain-first cases where the source is located in the brain and only 0.1–0.2% of nAbs cross the blood–brain barrier. Abbreviations: nAbs: naturally occurring autoantibodies; DMV: dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus; LC: locus coeruleus; SN: substantia nigra, PAF: pure autonomic failure, PSG: polysomnography, BBB: blood brain barrier. Created using Biorender.com (accessed on 30 November 2021).

References

- Spillantini, M.G.; Schmidt, M.L.; Lee, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Jakes, R.; Goedert, M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 1997, 388, 839–840.

- Polymeropoulos, M.H.; Lavedan, C.; Leroy, E.; Ide, S.E.; Dehejia, A.; Dutra, A.; Pike, B.; Root, H.; Rubenstein, J.; Boyer, R.; et al. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science 1997, 276, 2045–2047.

- Chartier-Harlin, M.-C.; Kachergus, J.; Roumier, C.; Mouroux, V.; Douay, X.; Lincoln, S.; Levecque, C.; Larvor, L.; Andrieux, J.; Hulihan, M.; et al. Alpha-synuclein locus duplication as a cause of familial Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2004, 364, 1167–1169.

- Singleton, A.B.; Farrer, M.; Johnson, J.; Singleton, A.; Hague, S.; Kachergus, J.; Hulihan, M.; Peuralinna, T.; Dutra, A.; Nussbaum, R.; et al. alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science 2003, 302, 841.

- Visanji, N.P.; Lang, A.E.; Kovacs, G.G. Beyond the synucleinopathies: Alpha synuclein as a driving force in neurodegenerative comorbidities. Transl. Neurodegener. 2019, 8, 28.

- Papp, M.I.; Kahn, J.E.; Lantos, P.L. Glial cytoplasmic inclusions in the CNS of patients with multiple system atrophy (striatonigral degeneration, olivopontocerebellar atrophy and Shy-Drager syndrome). J. Neurol. Sci. 1989, 94, 79–100.

- Jellinger, K.A.; Lantos, P.L. Papp-Lantos inclusions and the pathogenesis of multiple system atrophy: An update. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 657–667.

- Kovacs, G.G. Molecular Pathological Classification of Neurodegenerative Diseases: Turning towards Precision Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 189.

- Armstrong, M.J.; Emre, M. Dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson disease dementia: More different than similar? Neurology 2020, 94, 858–859.

- Borghammer, P. How does parkinson’s disease begin? Perspectives on neuroanatomical pathways, prions, and histology. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 48–57.

- Beach, T.G.; Adler, C.H.; Sue, L.I.; Vedders, L.; Lue, L.; White Iii, C.L.; Akiyama, H.; Caviness, J.N.; Shill, H.A.; Sabbagh, M.N.; et al. Multi-organ distribution of phosphorylated alpha-synuclein histopathology in subjects with Lewy body disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 689–702.

- Mendoza-Velásquez, J.J.; Flores-Vázquez, J.F.; Barrón-Velázquez, E.; Sosa-Ortiz, A.L.; Illigens, B.-M.W.; Siepmann, T. Autonomic Dysfunction in α-Synucleinopathies. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 363.

- Thaisetthawatkul, P. Pure Autonomic Failure. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2016, 16, 74.

- Palma, J.-A.; Norcliffe-Kaufmann, L.; Kaufmann, H. Diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Auton. Neurosci. 2018, 211, 15–25.

- Borghammer, P. The α-Synuclein Origin and Connectome Model (SOC Model) of Parkinson’s Disease: Explaining Motor Asymmetry, Non-Motor Phenotypes, and Cognitive Decline. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2021, 11, 455–474.

- Borghammer, P.; Horsager, J.; Andersen, K.; Van Den Berge, N.; Raunio, A.; Murayama, S.; Parkkinen, L.; Myllykangas, L. Neuropathological evidence of body-first vs. brain-first Lewy body disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 161, 105557.

- Albus, A.; Jördens, M.; Möller, M.; Dodel, R. Encoding the Sequence of Specific Autoantibodies Against beta-Amyloid and alpha-Synuclein in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2033.

- Games, D.; Valera, E.; Spencer, B.; Rockenstein, E.; Mante, M.; Adame, A.; Patrick, C.; Ubhi, K.; Nuber, S.; Sacayon, P.; et al. Reducing C-terminal-truncated α-synuclein by immunotherapy attenuates neurodegeneration and propagation in Parkinson’s disease-like models. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 9441–9454.

- Bergström, A.L.; Kallunki, P.; Fog, K. Development of Passive Immunotherapies for Synucleinopathies. Mov. Disord. 2015, 31, 16–21.

- Antonini, A.; Bravi, D.; Sandre, M.; Bubacco, L. Immunization therapies for Parkinson’s disease: State of the art and considerations for future clinical trials. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2020, 29, 685–695.

- Li, X.; Koudstaal, W.; Fletcher, L.; Costa, M.; van Winsen, M.; Siregar, B.; Inganäs, H.; Kim, J.; Keogh, E.; Macedo, J.; et al. Naturally occurring antibodies isolated from PD patients inhibit synuclein seeding in vitro and recognize Lewy pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 137, 825–836.

- Scott, K.M.; Kouli, A.; Yeoh, S.L.; Clatworthy, M.R.; Williams-Gray, C.H. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Alpha Synuclein Auto-Antibodies in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 815.

- Brudek, T.; Winge, K.; Folke, J.; Christensen, S.; Fog, K.; Pakkenberg, B.; Pedersen, L.O. Autoimmune antibody decline in Parkinson’s disease and Multiple System Atrophy; a step towards immunotherapeutic strategies. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 44.

- Folke, J.; Rydbirk, R.; Løkkegaard, A.; Salvesen, L.; Hejl, A.-M.; Starhof, C.; Bech, S.; Winge, K.; Christensen, S.; Pedersen, L.Ø.; et al. Distinct Autoimmune Anti-α-Synuclein Antibody Patterns in Multiple System Atrophy and Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2253.

- Folke, J.; Rydbirk, R.; Løkkegaard, A.; Hejl, A.-M.; Winge, K.; Starhof, C.; Salvesen, L.; Pedersen, L.Ø.; Aznar, S.; Pakkenberg, B.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma distribution of anti-α-synuclein IgMs and IgGs in multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2021, 87, 98–104.

- Chartier, S.; Duyckaerts, C. Is Lewy pathology in the human nervous system chiefly an indicator of neuronal protection or of toxicity? Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 373, 149–160.

- Ingelsson, M. Alpha-Synuclein Oligomers-Neurotoxic Molecules in Parkinson’s Disease and Other Lewy Body Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 408.

- Masliah, E.; Rockenstein, E.; Mante, M.; Crews, L.; Spencer, B.; Adame, A.; Patrick, C.; Trejo, M.; Ubhi, K.; Rohn, T.T.; et al. Passive immunization reduces behavioral and neuropathological deficits in an alpha-synuclein transgenic model of lewy body disease. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19338.

- Masliah, E.; Rockenstein, E.; Adame, A.; Alford, M.; Crews, L.; Hashimoto, M.; Seubert, P.; Lee, M.; Goldstein, J.; Chilcote, T.; et al. Effects of alpha-synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 2005, 46, 857–868.

- Spencer, B.; Valera, E.; Rockenstein, E.; Overk, C.; Mante, M.; Adame, A.; Zago, W.; Seubert, P.; Barbour, R.; Schenk, D.; et al. Anti-α-synuclein immunotherapy reduces α-synuclein propagation in the axon and degeneration in a combined viral vector and transgenic model of synucleinopathy. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2017, 5, 7.

- Bae, E.-J.; Lee, H.-J.; Rockenstein, E.; Ho, D.-H.; Park, E.-B.; Yang, N.-Y.; Desplats, P.; Masliah, E.; Lee, S.-J. Antibody-aided clearance of extracellular α-synuclein prevents cell-to-cell aggregate transmission. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 13454–13469.

- Tran, H.T.; Chung, C.H.-Y.; Iba, M.; Zhang, B.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Luk, K.C.; Lee, V.M.Y. A-synuclein immunotherapy blocks uptake and templated propagation of misfolded α-synuclein and neurodegeneration. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 2054–2065.

- Shahaduzzaman, M.; Nash, K.; Hudson, C.; Sharif, M.; Grimmig, B.; Lin, X.; Bai, G.; Liu, H.; Ugen, K.E.; Cao, C.; et al. Anti-human α-synuclein N-terminal peptide antibody protects against dopaminergic cell death and ameliorates behavioral deficits in an AAV-α-synuclein rat model of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116841.

- Henderson, M.X.; Covell, D.J.; Chung, C.H.-Y.; Pitkin, R.M.; Sandler, R.M.; Decker, S.C.; Riddle, D.M.; Zhang, B.; Gathagan, R.J.; James, M.J.; et al. Characterization of novel conformation-selective α-synuclein antibodies as potential immunotherapeutic agents for Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 136, 104712.

- Chen, Y.-H.; Wu, K.-J.; Hsieh, W.; Harvey, B.K.; Hoffer, B.J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, S.-J. Administration of AAV-Alpha Synuclein NAC Antibody Improves Locomotor Behavior in Rats Overexpressing Alpha Synuclein. Genes 2021, 12, 948.

- Gorbatyuk, O.S.; Li, S.; Nash, K.; Gorbatyuk, M.; Lewin, A.S.; Sullivan, L.F.; Mandel, R.J.; Chen, W.; Meyers, C.; Manfredsson, F.P.; et al. In vivo RNAi-mediated alpha-synuclein silencing induces nigrostriatal degeneration. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 1450–1457.

- Lindström, V.; Fagerqvist, T.; Nordström, E.; Eriksson, F.; Lord, A.; Tucker, S.; Andersson, J.; Johannesson, M.; Schell, H.; Kahle, P.J.; et al. Immunotherapy targeting α-synuclein protofibrils reduced pathology in (Thy-1)-h α-synuclein mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 69, 134–143.

- Kahle, P.J.; Neumann, M.; Ozmen, L.; Muller, V.; Jacobsen, H.; Schindzielorz, A.; Okochi, M.; Leimer, U.; van Der Putten, H.; Probst, A.; et al. Subcellular localization of wild-type and Parkinson’s disease-associated mutant alpha -synuclein in human and transgenic mouse brain. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 6365–6373.

- Kallab, M.; Herrera-Vaquero, M.; Johannesson, M.; Eriksson, F.; Sigvardson, J.; Poewe, W.; Wenning, G.K.; Nordström, E.; Stefanova, N. Region-Specific Effects of Immunotherapy with Antibodies Targeting α-synuclein in a Transgenic Model of Synucleinopathy. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 452.

- Nordström, E.; Eriksson, F.; Sigvardson, J.; Johannesson, M.; Kasrayan, A.; Jones-Kostalla, M.; Appelkvist, P.; Söderberg, L.; Nygren, P.; Blom, M.; et al. ABBV-0805, a novel antibody selective for soluble aggregated α-synuclein, prolongs lifespan and prevents buildup of α-synuclein pathology in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 161, 105543.

- El-Agnaf, O.; Overk, C.; Rockenstein, E.; Mante, M.; Florio, J.; Adame, A.; Vaikath, N.; Majbour, N.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, C.; et al. Differential effects of immunotherapy with antibodies targeting α-synuclein oligomers and fibrils in a transgenic model of synucleinopathy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2017, 104, 85–96.

- Schofield, D.J.; Irving, L.; Calo, L.; Bogstedt, A.; Rees, G.; Nuccitelli, A.; Narwal, R.; Petrone, M.; Roberts, J.; Brown, L.; et al. Preclinical development of a high affinity α-synuclein antibody, MEDI1341, that can enter the brain, sequester extracellular α-synuclein and attenuate α-synuclein spreading in vivo. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 132, 104582.

- Huang, Y.-R.; Xie, X.-X.; Ji, M.; Yu, X.-L.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.-X.; Liu, X.-G.; Wei, C.; Li, G.; Liu, R.-T. Naturally occurring autoantibodies against α-synuclein rescues memory and motor deficits and attenuates α-synuclein pathology in mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 124, 202–217.

- Weihofen, A.; Liu, Y.; Arndt, J.W.; Huy, C.; Quan, C.; Smith, B.A.; Baeriswyl, J.-L.; Cavegn, N.; Senn, L.; Su, L.; et al. Development of an aggregate-selective, human-derived α-synuclein antibody BIIB054 that ameliorates disease phenotypes in Parkinson’s disease models. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 124, 276–288.

- Kuo, Y.-M.; Li, Z.; Jiao, Y.; Gaborit, N.; Pani, A.K.; Orrison, B.M.; Bruneau, B.G.; Giasson, B.I.; Smeyne, R.J.; Gershon, M.D.; et al. Extensive enteric nervous system abnormalities in mice transgenic for artificial chromosomes containing Parkinson disease-associated alpha-synuclein gene mutations precede central nervous system changes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 1633–1650.

- Ghosh, S.S.; Wang, J.; Yannie, P.J.; Ghosh, S. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction, LPS Translocation, and Disease Development. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvz039.

- van IJzendoorn, S.C.D.; Derkinderen, P. The Intestinal Barrier in Parkinson’s Disease: Current State of Knowledge. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2019, 9, S323–S329.

- Boertien, J.M.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Aho, V.T.E.; Scheperjans, F. Increasing Comparability and Utility of Gut Microbiome Studies in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2019, 9, S297–S312.

- Brudek, T. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Parkinson’s Disease. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2019, 9, S331–S344.

- Lee, H.-S.; Lobbestael, E.; Vermeire, S.; Sabino, J.; Cleynen, I. Inflammatory bowel disease and Parkinson’s disease: Common pathophysiological links. Gut 2021, 70, 408–417.

- Jan, A.; Gonçalves, N.P.; Vaegter, C.B.; Jensen, P.H.; Ferreira, N. The Prion-Like Spreading of Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease: Update on Models and Hypotheses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8338.

- Borghammer, P.; Van Den Berge, N. Brain-First versus Gut-First Parkinson’s Disease: A Hypothesis. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2019, 9, S281–S295.

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912.

- Knudsen, K.; Haase, A.-M.; Fedorova, T.D.; Bekker, A.C.; Østergaard, K.; Krogh, K.; Borghammer, P. Gastrointestinal Transit Time in Parkinson’s Disease Using a Magnetic Tracking System. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2017, 7, 471–479.