Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Afshin Omidi.

At the intersection of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and human resource management (HRM), a specific research strand has been forming and considerably flourishing over the past years, contributing to the burgeoning academic debate of what has been called “socially responsible human resource management” (SRHRM). The SRHRM debate seeks to proactively enhance employees’ work experiences and meet their personal and social expectations in ethical and socially responsible ways.

- corporate social responsibility

- SRHRM

- ethical HRM

- internal CSR

- responsible management

1. Introduction

As corporations are an integral part of contemporary society with their operations impacting a wide array of stakeholders, unsurprisingly, the idea of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has been gaining momentum in management research over the last decades [1]. While prior research in this area, not all though, has instrumentally been attempting to find a link between CSR plans and positive financial results for firms [2[2][3],3], it has been argued that CSR intentions have gone beyond financial results [4], thereby more actively contributing to solving societal and grand challenges [5,6,7][5][6][7]. Increasing interest in CSR research has partially been rooted in a rationale that considers organizations as critical in reaching a sustainable society [8]. Some authors [9] contended that CSR initiatives are “voluntary” activities of corporations that could bring positive results in different realms of societies. However, this “voluntary” viewpoint is challenged by an intensifying globalization, and one might argue that the strict separation of private and public interests is no longer relevant [10]. Public states even failed in fully serving public and environmental demands to build a sustainable society [11]. Keeping this criticism in mind, Tamvada [12] insisted that CSR could not be seen as an optional provision; rather, it should even be regulated as mandatory obligation of a firm.

The strategic formulation of CSR priorities as well as their translation into everyday managerial practices has however represented a critical challenge for many organizations. As Jamali [13] argued, organizations responded to this challenge by emphasizing the role of human resource management (HRM). Indeed, HRM assumes a critical role as HR activities are highly intertwined with humanistic approaches in organizations [13,14][13][14] while contributing to business value creation at the same time [15,16][15][16]. It is thus not surprising to see that prior research has considerably sought to relate CSR with HRM [17,18][17][18]. The linkage between CSR and HRM can be critical for organizations to, for instance, make sense of the ethical assumptions about their role in societies, improve relationships between themselves and employees [2], and solve the paradoxical tensions (i.e., conflictual interests of different stakeholders) that may occur during CSR initiatives [19].

At the intersection of CSR and HRM, a specific research strand has been forming and considerably flourishing over the last years, contributing to the burgeoning academic debate of what has been called “internal corporate social responsibility” or, as addressed in the present paper, “socially responsible human resource management” (SRHRM) [20,21][20][21]. A critical reason for the increasing research interest in this area has been the shortage of insights in CSR literature about its internal stakeholders, i.e., employees [22]. It makes sense to argue that organizations must have a socially responsible approach towards employees, as they will finally implement CSR strategies to responsibly serve external stakeholders. In fact, socially responsible HRM practices could for instance help organizations increase their employees’ ethical awareness and meaningfully motivate them to engage in CSR activities [23].

Finding a universal definition for SRHRM could be a daunting task as this concept is rooted in ethical imperatives and, hence, is highly contextual [24]. We thus hold that SRHRM activities are not merely attempting to provide employees with good working conditions based on legal requirements and regulations (e.g., minimum wage). Instead, they seek to proactively enhance employees’ work experiences and meet their personal and social expectations in ethical and socially responsible ways [25]. Indeed, the SRHRM debate moves the ethical issues concerning employees beyond their instrumental value for organizational aims. It also intends to express deep care for fulfilling organizational members’ personal and professional expectations, thereby genuinely contributing to the employees’ well-being and societal demands [26]. With growing public demands and pressures to shift corporate priorities from mere profitability to responsible and sustainable approaches to management, the HRM field must play a leading role in driving and implementing such plans in practice [27]. To reach this aim, a holistic understanding of the latest advancements in the field could help HRM scholars to more wisely explore current challenges and potential gaps in SRHRM, thereby moving toward a higher level of sustainable management of organizations.

2. Researches and findings

2.1. Bibliometrics

Table 1 shows 26 journals that published empirical research in SRHRM. Accordingly, the Sustainability journal was ranked first by publishing 13 relevant studies in this area, followed by The International Journal of Human Resource Management (n = 7) and Journal of Business Ethics (n = 5) in the second and third ranks, respectively. It seems that these three journals will remain one of the most attractive targets for prospective researchers who wish to publish their studies in SRHRM. The publishing journals come from several academic publishers, including MDPI, Taylor and Francis, Springer, Emerald, Wiley, Elsevier, and Sage. The journals’ scope that published research in this domain is varied, including business ethics, environmental sciences, CSR, HRM, public health, strategic management, to name but a few. The varieties of the journals indicate the interdisciplinary nature of the SRHRM research field, which is connected with, and can have critical implications for, a wide array of issues in societies.

Table 1.

Journals that published empirical research in SRHRM.

| No. | Journal | Publisher | Frequency | Percentage | Source(s) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sustainability | MDPI | 13 | 22.81% | Shen and Jiuhua Zhu [21]; Newman et al. [62]; Shen and Benson [94]; Shen et al. [ | ; Shen and Benson [ | 88]; Lin-Hi et al. [ | 75 | 79]; Jia et al. [ | ]; Shen et al. [69] | 74]; Shen and Zhang [67]; Shao et al. [51]; Shao, Zhou, and Gao [ | ; Lin-Hi et al. [60]; Jia et al. [55]; Shen and Zhang [48]; Shao et al. [ | 52]; Zhao and Zhou [92]; He et al. [76]; He and Kim [57]; Zhang et al. [68]; Zhao et al. [69]; Li et al. [99] | Shen and Jiuhua Zhu [21]; Newman et al. [43]32]; Shao, Zhou, and Gao [33]; Zhao and Zhou [73]; He et al. [57]; He and Kim [38]; Zhang et al. [49]; Zhao et al. [50]; Li et al. [80] | Obrad and Gherhes [47]; Barrena-Martinez et al. [48]; López-Fernández et al. [49]; Bombiak and Marciniuk-Kluska [50]; Shao et al. [51]; Shao, Zhou, and Gao [52]; García Mestanza et al. [53]; Revuelto-Taboada et al. [54]; Sobhani et al. [55]; Koinig and Weder [56]; He and Kim [57]; Adu-Gyamfi et al. [58]; Chang et al. [59] | Obrad and Gherhes [28]; Barrena-Martinez et al. [29]; López-Fernández et al. [30]; Bombiak and Marciniuk-Kluska [31]; Shao et al. [32]; Shao, Zhou, and Gao [33]; García Mestanza et al. [34]; Revuelto-Taboada et al. [35]; Sobhani et al. [36]; Koinig and Weder [37]; He and Kim [38]; Adu-Gyamfi et al. [39]; Chang et al. [40] |

| 2 | The International Journal of Human Resource Management | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | Taylor and Francis | 7 | 12.29% | Spain | 13 | 22.81% | Barrena-Martínez et al. [81]; Celma et al. [82]; Lechuga Sancho et al. [97]; Barrena-Martinez et al. [48]; López-Fernández et al. [49]; Barrena-Martinez et al. [70]; García Mestanza et al. [53]; Barrena-Martínez et al. [64]; Sánchez-Hernández et al. [91]; Sorribes et al. [72]; Ramos-González et al. [90]; Revuelto-Taboada et al. [54]; Espasandín-Bustelo et al. [80] | Barrena-Martínez et al. [62]; Celma et al. [63]; Lechuga Sancho et al. [78]; Barrena-Martinez et al. [29]; López-Fernández et al. [30]; Barrena-Martinez et al. [51]; García Mestanza et al. [34]; Barrena-Martínez et al. [45]; Sánchez-Hernández et al. [72]; Sorribes et al. [53]; Ramos-González et al. [71]; Revuelto-Taboada et al. [35]; Espasandín-Bustelo et al. [61] | Shen and Jiuhua Zhu [21]; D’Cruz and Noronha [60]; Parkes and Davis [61]; Newman et al. [62]; Mory et al. [63]; Barrena-Martínez et al. [64]; Richards and Sang [65] | Shen and Jiuhua Zhu [21]; D’Cruz and Noronha [41]; Parkes and Davis [42]; Newman et al. [43]; Mory et al. [44]; Barrena-Martínez et al. [45]; Richards and Sang [46] | ||||||

| 3 | Journal of Business Ethics | Springer | 5 | |||||||||||||

| 3 | 8.78% | Multi-country | 5 | 8.77% | Goergen et al. [93]; Diaz-Carrion et al. [78]; Gangi et al. [73]; Koinig and Weder [56]; Lythreatis et al. [89] | Goergen et al. [74]; Diaz-Carrion et al. [59]; Gangi et al. [54]; Koinig and Weder [37]; Lythreatis et al. | Tongo [66]; Shen and Zhang [ | ] | 67]; Heikkinen et al. [ | ; Shen and Zhang [48 | 26]; Zhang et al. [ | ]; Heikkinen et al. [ | 68]; Zhao et al. [69] | Tongo [4726]; Zhang et al. [49]; Zhao et al. [50] | ||

| [ | 70 | ] | 4 | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | Wiley | 4 | 7.02% | |||||||||

| 4 | USA | 3 | 5.26% | Shan et al. [100]; Brown [101]; Lee [84] | Shan et al. [81]; Brown [82]; Lee [65] | Barrena-Martinez et al. [70]; Lombardi et al. [71]; Sorribes et al. [ | [51]; Lombardi et al. [ | 72]; Gangi et al. [73] | Barrena-Martinez et al. 52]; Sorribes et al. [53]; Gangi et al. [54] | |||||||

| 5 | International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management | |||||||||||||||

| 5 | Emerald | 3 | 5.27% | Vietnam | 3 | 5.26% | D. T. Luu [96]; Luu [75]; Giang and Dung [98] | D. T. Luu [77]; Luu [56]; Giang and Dung [79] | Jia et al. [74]; Luu [75]; He et al. [76] | Jia et al. [55]; Luu [56]; He et al. [57] | ||||||

| 6 | ||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Business Ethics: A European Review | Wiley | 2 | Finland | 2 | 3.52% | 3.52% | Nie et al. [77]; Heikkinen et al. [ | Nie et al. [ | 26] | 58]; Heikkinen et al. | Nie et al. [77]; Diaz-Carrion et al. [78] | Nie et al. [58]; Diaz-Carrion et al. [59] | |||

| [ | 26 | 7 | Employee Relations: The International Journal | Emerald | 2 | 3.52% | 60]; Chanda and Goyal [95] | D’Cruz and Noronha [41]; Chanda and Goyal [76] | Lin-Hi et al. [79]; Espasandín-Bustelo et al. [80] | Lin-Hi et al. [60]; Espasandín-Bustelo et al. [61] | ||||||

| 8 | European Research on Management and Business Economics | Elsevier | 2 | |||||||||||||

| 8 | 3.52% | Barrena-Martínez et al. [ | 81 | ]; Celma et al. [ | 82] | Italy | Barrena-Martínez et al. [62]; Celma et al. [63] | |||||||||

| 2 | 9 | Management Decision | Emerald | 2 | 3.52% | Jamali et al. [83]; Lee [84] | Jamali et al. [64]; Lee [65] | |||||||||

| 3.52% | Lombardi et al. [ | 71 | ]; Jamali et al. [ | 83] | Lombardi et al. [52]; Jamali et al. [64] | |||||||||||

| 9 | UK | 2 | 3.52% | Parkes and Davis [61]; Richards and Sang [65] | Parkes and Davis [42]; Richards and Sang [46] | 10 | Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources | Wiley | 1 | 1.75% | Sarvaiya and Arrowsmith [85] | |||||

| 10 | Bangladesh | Sarvaiya and Arrowsmith | 1 | 1.75% | Sobhani et al. [55] | Sobhani et al. [36][66] | ||||||||||

| 11 | Baltic Journal of Management | Emerald | ||||||||||||||

| 11 | Germany | 1 | 1 | 1.75% | 1.75% | Bučiūnienė and Kazlauskaitė [ | Mory et al. [63] | Mory et al. [44] | 86] | Bučiūnienė and Kazlauskaitė [67] | ||||||

| 12 | Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility | Wiley | 1 | 1.75% | Low and Bu [ | |||||||||||

| 12 | Ghana | 87 | 1 | 1.75% | Adu-Gyamfi et al. [58] | Adu-Gyamfi et al. [39] | ] | Low and Bu [68] | ||||||||

| 13 | Human Resource Management | |||||||||||||||

| 13 | Lithuania | Wiley | 1 | 1 | 1.75% | 1.75% | Bučiūnienė and Kazlauskaitė [86] | Bučiūnienė and Kazlauskaitė [67] | Shen et al. [88] | 1 | 1.75% | Lythreatis et al. [89] | Lythreatis et al. [70] | |||

| ] | ||||||||||||||||

| 7 | India | 2 | 3.52% | D’Cruz and Noronha [ | Shen et al. [69] | |||||||||||

| 14 | International Business Review | Elsevier | ||||||||||||||

| 14 | Malaysia | 1 | 1.75% | Low and Bu [ | 15 | International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal | Springer | 1 | 1.75% | Ramos-González et al. [90] | Ramos-González et al. [71] | |||||

| 87 | ] | Low and Bu | [ | 68] | ||||||||||||

| 15 | New Zealand | 1 | 1.75% | Sarvaiya and Arrowsmith [85] | Sarvaiya and Arrowsmith [66] | 16 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | MDPI | ||||||||

| 16 | Nigeria | 1 | 1.75% | Sánchez-Hernández et al. [ | 91] | Sánchez-Hernández et al. [72] | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1.75% | Tongo [ | 66 | ] | Tongo [47] | 17 | International Journal of Hospitality Management | Elsevier | 1 | 1.75% | Zhao and Zhou [92] | Zhao and Zhou [73] | ||||

| 18 | Journal of Corporate Finance | Elsevier | 1 | 1.75% | Goergen et al. [93] | Goergen et al. [74] | ||||||||||

| 19 | Journal of Management | Sage | 1 | 1.75% | Shen and Benson [94] | Shen and Benson [75] | ||||||||||

| 20 | Journal of Management Analytics | Taylor and Francis | 1 | 1.75% | Chanda and Goyal [95] | Chanda and Goyal [76] | ||||||||||

| 21 | Journal of Organizational Change Management | Emerald | 1 | 1.75% | D. T. Luu [96] | D. T. Luu [77] | ||||||||||

| 22 | Personnel Review | Emerald | 1 | 1.75% | Lechuga Sancho et al. [97] | Lechuga Sancho et al. [78] | ||||||||||

| 23 | Review of Managerial Science | Springer | 1 | 1.75% | Giang and Dung [98] | Giang and Dung [79] | ||||||||||

| 24 | SAGE Open | Sage | 1 | 1.75% | Li et al. [99] | Li et al. [80] | ||||||||||

| 25 | Strategic Management Journal | Wiley | 1 | 1.75% | Shan et al. [100] | Shan et al. [81] | ||||||||||

| 26 | The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science | Sage | 1 | 1.75% | Brown [101] | Brown [82] | ||||||||||

| Total | 57 | 100 | ||||||||||||||

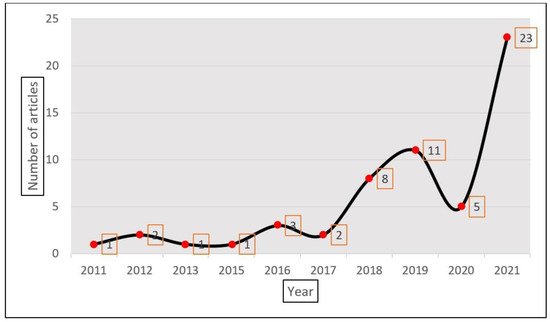

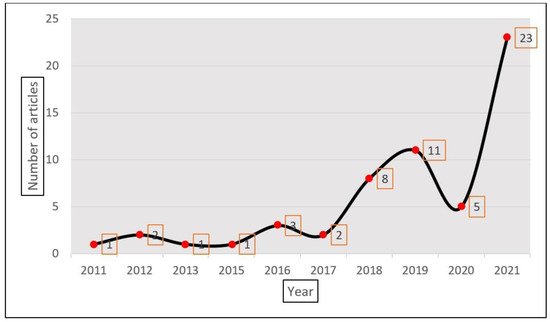

Figure 2 1 represents the distribution of studies in SRHRM research published from 2011 to 2021. Interestingly, the number of publications in this area received a sharp surge in 2021 (n = 21), making it the most prolific year over the last decade. As depicted in Figure 21, the number of publications from 2011 to 2017 was often the same (i.e., between one or two papers) in this area. However, SRHRM gained momentum in 2018 (n = 8) and culminated in 2021 with 23 published papers until November.

Figure 21.

Distribution of studies in SRHRM across years.

Table 2 shows the distribution of papers published in the SRHRM domain based on geographical data coverage. Most published articles pertain to China (n = 15), followed by Spain (n = 13) in the second rank. Five papers did not limit themselves to specific countries; instead, they simultaneously addressed SRHRM within several countries. As shown by Table 2, the countries covered by the empirical data gathered in previous papers come from different continents worldwide, including Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and Africa. According to the increasing interest in the SRHRM research over the last years, it is predicted that future empirical studies will cover more countries, thereby providing cross-cultural data for better understanding the contingencies that may exist within different national contexts.

Table 2.

Distribution of studies on SRHRM across countries based on geographical data coverage.

Table 3 categorizes the previous studies in SRHRM based on research approaches and methods. Most published papers employed a quantitative approach (n = 44) and tested previous scholars’ research models [20,21,94][20][21][75]. Qualitative (n = 7) and mixed (n = 6) approaches were also used in this field, though their size is not very significant compared to the quantitative studies. The proliferation of quantitative studies provides an excellent ground upon which to generalize the findings in the SRHRM domain, while the shortage of qualitative studies in this area signals a significant void to gain a more in-depth understanding of SRHRM dynamics and processes.

Table 3.

Distribution of studies in SRHRM based on research methods.

| No. | Research Approach | Methods and Techniques | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|

| 1 | Quantitative | Survey; Factor analysis; Hierarchical regression; Regression analysis; Structural equation modeling; Quantitative content analysis; Analysis of variance (ANOVA); Multivariate linear regression model (MLRM); Intra-class correlation (ICC1); Bayesian network model; Bivariate linear regression analysis; Bootstrapped multi-mediation analysis; PROCESS macro | 44 | 77.19% |

| 2 | Qualitative | Single-case study; In-depth interviews; Thematic analysis; Discourse analysis; Life history interviews; Document analysis | 7 | 12.28% |

| 3 | Mixed | Survey; correlation analysis; Open-ended questionnaires; Axial coding; Delphi method; Score analysis; Design thinking; Focus groups; Expert panels; Weight analysis; Multiple linear regression; Interviews | 6 | 10.53% |

| Total | 57 | 100 | ||

2.2. Antecedents of SRHRM

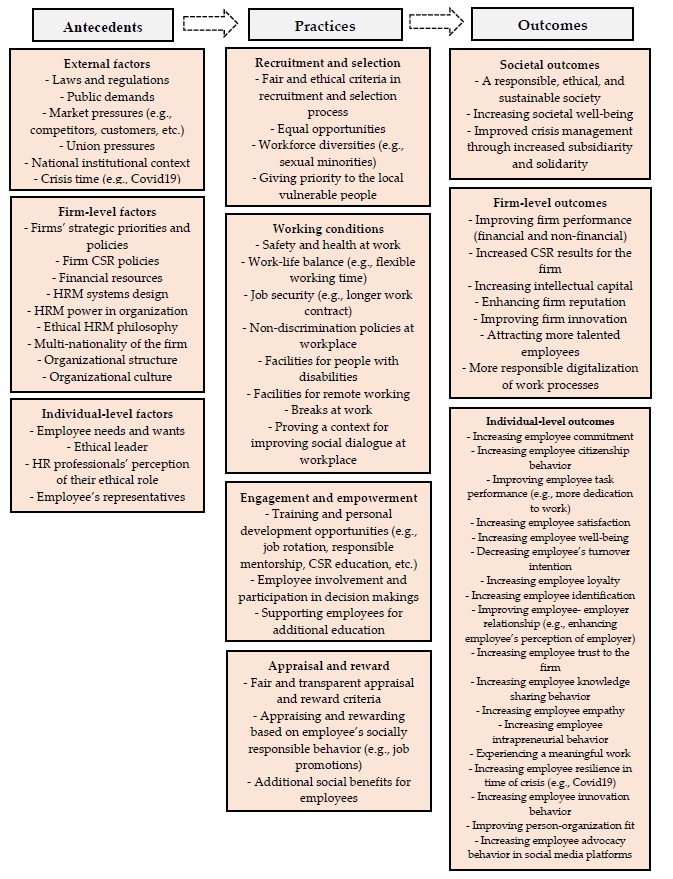

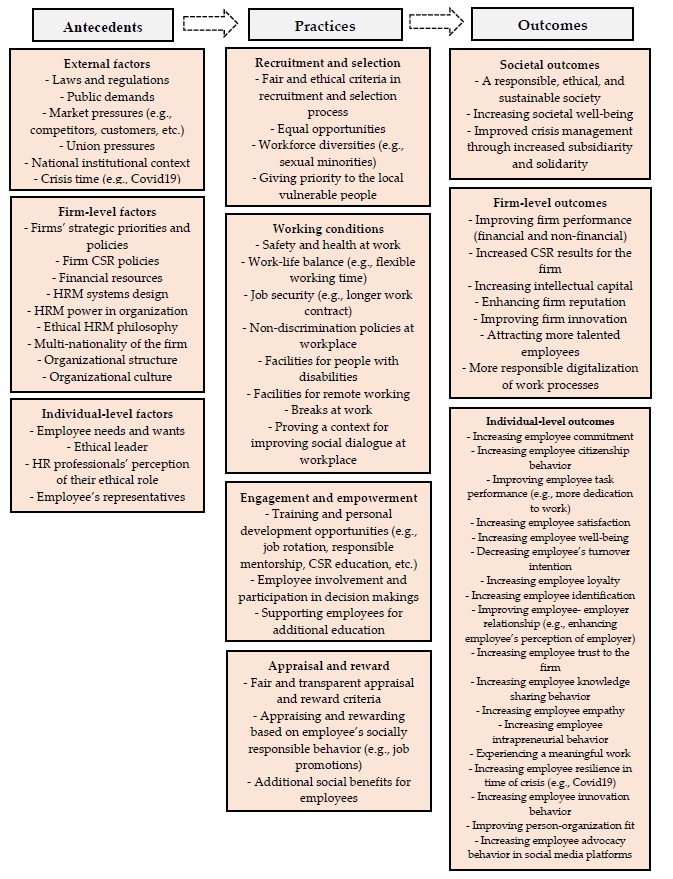

Concerning external factors, previous studies mentioned different items that could have an impact on the SRHRM practices, such as laws and regulations [21[21][43][47][81],62,66,100], public demand and expectations [61[42][45][73],64,92], market pressures induced by, for example, competitors and/or customers [26[26][34][55],53,74], union pressures such as those coming from the International Labour Organization (ILO) [48[29][43][47],62,66], the national institutional context [78[59][70],89], and external crisis, such as what all organizations experienced due to the COVID-19 pandemic since its appearance in 2019 [72,76][53][57]. The second group of antecedents pertains to the firm-level factors. Although all the reviewed papers assert that CSR firm policies impact SRHRM practices, some studies also explored other drivers within firms that might have been influential in this regard. Such factors include firms’ strategic policies and priorities [48[29][41],60], available financial resources [60][41], HRM systems design [60][41], HRM power in the organization [26], ethics-oriented HRM philosophies [65][46], the multi-nationality of firms [93][74], as well as organizational structure and culture [80][61]. The third antecedent category is related to the individual factors, including employees’ needs and wants [21[21][43][58][60],62,77,79], the presence of an ethical leader [60,61,75,89[41][42][56][70][73][82],92,101], the HR professionals’ perception of their ethical role [61][42], and the role of employees’ representatives in organizations [56][37].

2.3. Practices in SRHRM

SRHRM practices were mostly adapted from the traditional HRM functions (i.e., recruitment and selection, training and development, working conditions, appraisal and reward) by including ethical and fairness issues such as the consideration of work-life balance through, for example, flexible working time (e.g., [63][44]), enhanced communication at work (e.g., [62][43]), safety and health at work (e.g., [49][30]), transparent criteria in recruitment and selection (e.g., [54][35]), equal opportunities (e.g., [53][34]), fair appraisal processes (e.g., [78][59]), training opportunities and different personal development alternatives such as employee participation in decision-making (e.g., [86][67]), as well as providing additional support for employee education [83][64]. However, some studies that emphasize specific practices, less addressed by previously structured frameworks, are worth mentioning. In this vein, Shan et al. [100][81] call for considering sexual minorities to make the workplace diverse, Lombardi et al. [71][52] recommend embracing more extended work contracts to make the job more secure for the employees, and Obrad and Gherheș [47][28] note that facilities for people with disabilities and also for remote working should be provided. Moreover, Celma et al. [82][63] and Lin-Hi et al. [79][60] insist on devising non-discrimination policies at the workplace, and some studies hold that a context for social dialogue between employees and managers needs to be built [70,81,96,97,98][51][62][77][78][79].

2.4. Outcomes of SRHRM

At the macro level, Bombiak and Marciniuk-Kluska [50][31] assert that SRHRM practices provide a path for the sustainable development of organizations, which finally result in increasing societal well-being [78][59] and the building of a sustainable, responsible, and ethical society [53][34]. Concerning the firm-level outcomes, evidence shows that SRHRM practices could increase financial and non-financial firm performance [66,81,86[47][62][67][76][77],95,96], already achieved CSR firm results [86][67], intellectual capital [70][51], firm reputation [55,90][36][71], and even firm innovation [90][71]. Furthermore, Low and Bu [87][68] suggest that SRHRM practices can help the organization to implement the digitalization of work processes more committedly, while Parkes and Davis [61][42] contend that organizations could more quickly attract talents by employing SRHRM strategies.

Individual outcomes of SRHRM practices have been the most topical issue addressed by previous studies. In this regard, a considerable number of studies confirmed that SRHRM can have a positive impact on employee commitment [21,49,63,66,78,83,87,95,97][21][30][44][47][59][64][68][76][78]. Other individual factors positively affected by SRHRM practices include employee citizenship behavior [51,55,62[32][36][43][47][64][65][73],66,83,84,92], employee task performance [59[40][75],94], employee satisfaction [72[53][62][76],81,95], employee well-being [68[49][59],78], employee loyalty [101][82], the propensity of employees to identify themselves with their organization [59,83,88,89[40][64][69][70][72],91], employee–employer relationships [79[60][65],84], employee trust in the firm [72[53][55][57],74,76], employee empathy [52][33], employee knowledge sharing behavior [74][55], employee innovation behavior [54,99][35][80], and employee intrapreneurial behavior [96,98,99][77][79][80]. It has also been shown that SRHRM practices can help employees to make sense of their jobs in a meaningful way [75][56] and even make employees more resilient in times of crisis, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic [76][57]. Further positive outcomes include increasing employee advocacy behavior within social media platforms [84][65] and enhancing the person–organization fit [69][50]. Using SRHRM practices, organizations can also decrease employees’ intention to leave their organizations [55,77][36][58].

References

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968.

- Voegtlin, C.; Greenwood, M. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: A systematic review and conceptual analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 181–197.

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G.; Baumann, D. Global Rules and Private Actors: Toward a New Role of the Transnational Corporation in Global Governance. Bus. Ethics Q. 2006, 16, 505–532.

- Tulcanaza-Prieto, A.B.; Shin, H.; Lee, Y.; Lee, C. Relationship among CSR Initiatives and Financial and Non-Financial Corporate Performance in the Ecuadorian Banking Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1621.

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On Corporate Social Responsibility, Sensemaking, and the Search for Meaningfulness Through Work. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1057–1086.

- Wang, H.; Tong, L.; Takeuchi, R.; George, G. Corporate Social Responsibility: An Overview and New Research Directions. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 534–544.

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. Toward a political conception of corporate responsibility: Business and society seen from a habermasian perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1096–1120.

- Ashrafi, M.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R.; Magnan, G. How corporate social responsibility can be integrated into corporate sustainability: A theoretical review of their relationships. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 672–682.

- Kanji, G.K.; Chopra, P.K. Corporate social responsibility in a global economy. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2010, 21, 119–143.

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. The New Political Role of Business in a Globalized World: A Review of a New Perspective on CSR and its Implications for the Firm, Governance, and Democracy. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 899–931.

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G.; Matten, D. The Business Firm as a Political Actor. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 143–156.

- Tamvada, M. Corporate social responsibility and accountability: A new theoretical foundation for regulating CSR. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2020, 5, 2.

- Jamali, D.; El Dirani, A.M.; Harwood, I.A. Exploring human resource management roles in corporate social responsibility: The CSR-HRM co-creation model. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2015, 24, 125–143.

- Nejati, M.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Loke, C.K. Can ethical leaders drive employees’ CSR engagement? Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 16, 655–669.

- Cantele, S. Human resources management in responsible small businesses: Why, how and for what? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2018, 18, 112.

- Dal Zotto, C.; Gustafsson, V. Human resource management as an entrepreneurial tool. In International Handbook of Entrepreneurship and HRM; Barrett, R., Mayson, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 89–110.

- Sarvaiya, H.; Eweje, G.; Arrowsmith, J. The Roles of HRM in CSR: Strategic Partnership or Operational Support? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 825–837.

- Podgorodnichenko, N.; Edgar, F.; Akmal, A. An integrative literature review of the CSR-HRM nexus: Learning from research-practice gaps. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2021, 100839.

- Podgorodnichenko, N.; Edgar, F.; McAndrew, I. The role of HRM in developing sustainable organizations: Contemporary challenges and contradictions. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100685.

- Orlitzky, M.; Swanson, D.L. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management: Charting New Territory. In Human Resource Management Ethics; Deckop, J.R., Ed.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2006; pp. 3–25.

- Shen, J.; Jiuhua Zhu, C. Effects of socially responsible human resource management on employee organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 3020–3035.

- Frynas, J.G.; Yamahaki, C. Corporate social responsibility: Review and roadmap of theoretical perspectives. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 258–285.

- Liao, Z.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Q. Socially responsible human resource management and employee ethical voice: Roles of employee ethical and organizational identification. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 1–10.

- Lähteenmäki, S.; Laiho, M. Global HRM and the dilemma of competing stakeholder interests. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 166–180.

- Greige Frangieh, C.; Khayr Yaacoub, H. Socially responsible human resource practices: Disclosures of the world’s best multinational workplaces. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 277–295.

- Heikkinen, S.; Lämsä, A.-M.; Niemistö, C. Work–Family Practices and Complexity of Their Usage: A Discourse Analysis Towards Socially Responsible Human Resource Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 815–831.

- Baek, P.; Kim, T. Socially Responsible HR in Action: Learning from Corporations Listed on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index World 2018/2019. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3237.

- Obrad, C.; Gherheș, V. A Human Resources Perspective on Responsible Corporate Behavior. Case Study: The Multinational Companies in Western Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 726.

- Barrena-Martinez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernandez, P. Drivers and Barriers in Socially Responsible Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1532.

- López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M.; Aust, I. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management and Employee Perception: The Influence of Manager and Line Managers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4614.

- Bombiak, E.; Marciniuk-Kluska, A. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management as a Concept of Fostering Sustainable Organization-Building: Experiences of Young Polish Companies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1044.

- Shao, D.; Zhou, E.; Gao, P.; Long, L.; Xiong, J. Double-Edged Effects of Socially Responsible Human Resource Management on Employee Task Performance and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Mediating by Role Ambiguity and Moderating by Prosocial Motivation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2271.

- Shao, D.; Zhou, E.; Gao, P. Influence of Perceived Socially Responsible Human Resource Management on Task Performance and Social Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3195.

- García Mestanza, J.; Cerezo Medina, A.; Cruz Morato, M.A. A Model for Measuring Fair Labour Justice in Hotels: Design for the Spanish Case. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4639.

- Revuelto-Taboada, L.; Canet-Giner, M.T.; Balbastre-Benavent, F. High-Commitment Work Practices and the Social Responsibility Issue: Interaction and Benefits. Sustainability 2021, 13, 459.

- Sobhani, F.A.; Haque, A.; Rahman, S. Socially Responsible HRM, Employee Attitude, and Bank Reputation: The Rise of CSR in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2753.

- Koinig, I.; Weder, F. Employee Representatives and a Good Working Life: Achieving Social and Communicative Sustainability for HRM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7537.

- He, J.; Kim, H. The Effect of Socially Responsible HRM on Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: A Proactive Motivation Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7958.

- Adu-Gyamfi, M.; He, Z.; Nyame, G.; Boahen, S.; Frempong, M.F. Effects of Internal CSR Activities on Social Performance: The Employee Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6235.

- Chang, Y.-P.; Hu, H.-H.; Lin, C.-M. Consistency or Hypocrisy? The Impact of Internal Corporate Social Responsibility on Employee Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9494.

- D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Cornered by conning: Agents’ experiences of closure of a call centre in India. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1019–1039.

- Parkes, C.; Davis, A.J. Ethics and social responsibility—Do HR professionals have the ‘courage to challenge’ or are they set to be permanent ‘bystanders’? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2411–2434.

- Newman, A.; Miao, Q.; Hofman, P.S.; Zhu, C.J. The impact of socially responsible human resource management on employees’ organizational citizenship behaviour: The mediating role of organizational identification. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 440–455.

- Mory, L.; Wirtz, B.W.; Göttel, V. Factors of internal corporate social responsibility and the effect on organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1393–1425.

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. Towards a configuration of socially responsible human resource management policies and practices: Findings from an academic consensus. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 2544–2580.

- Richards, J.; Sang, K. Socially ir responsible human resource management? Conceptualising HRM practice and philosophy in relation to in-work poverty in the UK. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 2185–2212.

- Tongo, C.I. Social Responsibility, Quality of Work Life and Motivation to Contribute in the Nigerian Society. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 219–233.

- Shen, J.; Zhang, H. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management and Employee Support for External CSR: Roles of Organizational CSR Climate and Perceived CSR Directed Toward Employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 875–888.

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Jia, M. Multilevel Examination of How and When Socially Responsible Human Resource Management Improves the Well-Being of Employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 176, 55–71.

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q.; He, P.; Jiang, C. How and When Does Socially Responsible HRM Affect Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviors Toward the Environment? J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 371–385.

- Barrena-Martinez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. The link between socially responsible human resource management and intellectual capital. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 71–81.

- Lombardi, R.; Manfredi, S.; Cuozzo, B.; Palmaccio, M. The profitable relationship among corporate social responsibility and human resource management: A new sustainable key factor. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2657–2667.

- Sorribes, J.; Celma, D.; Martínez-Garcia, E. Sustainable human resources management in crisis contexts: Interaction of socially responsible labour practices for the wellbeing of employees. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 936–952.

- Gangi, F.; D’Angelo, E.; Daniele, L.M.; Varrone, N. Assessing the impact of socially responsible human resources management on company environmental performance and cost of debt. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1511–1527.

- Jia, X.; Liao, S.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Guo, Z. The effect of socially responsible human resource management (SRHRM) on frontline employees’ knowledge sharing. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3646–3663.

- Luu, T.T. Socially responsible human resource practices and hospitality employee outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 757–789.

- He, J.; Mao, Y.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. On being warm and friendly: The effect of socially responsible human resource management on employee fears of the threats of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 346–366.

- Nie, D.; Lämsä, A.-M.; Pučėtaitė, R. Effects of responsible human resource management practices on female employees’ turnover intentions. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2018, 27, 29–41.

- Diaz-Carrion, R.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernandez, P.M. Evidence of different models of socially responsible HRM in Europe. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 1–18.

- Lin-Hi, N.; Rothenhöfer, L.; Blumberg, I. The relevance of socially responsible blue-collar human resource management. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2019, 41, 1256–1272.

- Espasandín-Bustelo, F.; Ganaza-Vargas, J.; Diaz-Carrion, R. Employee happiness and corporate social responsibility: The role of organizational culture. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2021, 43, 609–629.

- Barrena-Martínez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernández, P.M. Socially responsible human resource policies and practices: Academic and professional validation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 23, 55–61.

- Celma, D.; Martinez-Garcia, E.; Raya, J.M. Socially responsible HR practices and their effects on employees’ wellbeing: Empirical evidence from Catalonia, Spain. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 24, 82–89.

- Jamali, D.; Samara, G.; Zollo, L.; Ciappei, C. Is internal CSR really less impactful in individualist and masculine Cultures? A multilevel approach. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 362–375.

- Lee, Y. Bridging employee advocacy in anonymous social media and internal corporate social responsibility (CSR). Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 2473–2495.

- Sarvaiya, H.; Arrowsmith, J. Exploring the context and interface of corporate social responsibility and HRM. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2021.

- Bučiūnienė, I.; Kazlauskaitė, R. The linkage between HRM, CSR and performance outcomes. Balt. J. Manag. 2012, 7, 5–24.

- Low, M.P.; Bu, M. Examining the impetus for internal CSR Practices with digitalization strategy in the service industry during COVID-19 pandemic. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2021, 31, 209–223.

- Shen, J.; Kang, H.; Dowling, P.J. Conditional altruism: Effects of HRM practices on the willingness of host-country nationals to help expatriates. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 355–364.

- Lythreatis, S.; Mostafa, A.M.S.; Pereira, V.; Wang, X.; Giudice, M. Del Servant leadership, CSR perceptions, moral meaningfulness and organizational identification- evidence from the Middle East. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101772.

- Ramos-González, M.d.M.; Rubio-Andrés, M.; Sastre-Castillo, M.Á. Effects of socially responsible human resource management (SR-HRM) on innovation and reputation in entrepreneurial SMEs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 321–368.

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Robina-Ramirez, R.; Díaz-Caro, C. Responsible Job Design Based on the Internal Social Responsibility of Local Governments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3994.

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q. Socially responsible human resource management and hotel employee organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A social cognitive perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102749.

- Goergen, M.; Chahine, S.; Wood, G.; Brewster, C. The relationship between public listing, context, multi-nationality and internal CSR. J. Corp. Financ. 2019, 57, 122–141.

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR Is a Social Norm: How Socially Responsible Human Resource Management Affects Employee Work Behavior. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1723–1746.

- Chanda, U.; Goyal, P. A Bayesian network model on the interlinkage between Socially Responsible HRM, employee satisfaction, employee commitment and organizational performance. J. Manag. Anal. 2020, 7, 105–138.

- Luu, D.T. The effect of internal corporate social responsibility practices on pharmaceutical firm’s performance through employee intrapreneurial behaviour. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 1375–1400.

- Lechuga Sancho, M.P.; Martínez-Martínez, D.; Larran Jorge, M.; Herrera Madueño, J. Understanding the link between socially responsible human resource management and competitive performance in SMEs. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 1211–1243.

- Giang, H.T.T.; Dung, L.T. The effect of internal corporate social responsibility practices on firm performance: The mediating role of employee intrapreneurial behaviour. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021.

- Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, L. Platform Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Innovation Performance: A Cross-Layer Study Mediated by Employee Intrapreneurship. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 1–13.

- Shan, L.; Fu, S.; Zheng, L. Corporate sexual equality and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1812–1826.

- Brown, W.S. Socially Responsible Entrepreneurship as Innovative Human Resource Practice. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2018, 54, 171–186.

More