In Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients, the progressive nature of the disease and the variability of disabling motor and non-motor symptoms contribute to the growing caregiver burden (CB) of PD partners and conflicts in their relationships. In advanced stages of the disease, Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) improves PD symptoms and patients quality of life but the effect of DBS on CB of PD partners seems to be heterogeneous. This review aims to illuminate CB in the context of DBS framing both pre-, peri- and postoperative aspects and to stimulate ims to be illuminated, and further recognition of caregiver burden in partners of PD patients with DBS will be stimulated.

- caregiver burden

- Parkinson’s disease

- deep brain stimulation

- neuropsychiatric symptoms

- burden of normality

- caregiver coping capability

- marital conflicts

1. Introduction

Caregiver burden (CB) has been defined as “the extent to which caregivers perceive that caregiving has an adverse effect on their emotional, social, financial, physical and spiritual functioning” [1] and occurs in the context of providing informal care for relatives with chronic diseases. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex disorder with increasing disabling motor and non-motor symptoms over time, which results in an increased risk of CB in partners of PD. In advanced stages of the disease, higher symptom severity of PD patients is associated with higher CB of their partners [2]. Non-motor symptoms seem to impact CB even more than motor impairment [3]. CB can have detrimental effects on the quality of caregiving, as well as the mental health of the caregiver. Therefore, it is pivotal to engage further family members to uncover and reduce CB and prevent premature institutionalization [4] [5].

In advanced disease stages, device-aided therapies as Deep Brain stimulation (DBS) provide substantial improvement of PD symptoms and quality of life (QOL) [6] [7]. It is of interest, whether caregiver also profit from DBS in terms of CB reduction, since DBS might be associated with side effects or postoperative changes of the marital relationship due to the sudden motor symptom improvement in the sense of burden of normality. This review aims to provide a concise overview of factors contributing to CB in PD in the context of DBS.

2. Preoperative Caregiver Burden—DBS Yes or No?

2.1. Caregiver Burden Due to Insufficient PD Symptom Control in Advanced Stages

2.2. Caregiver Expectations of DBS

Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN-DBS) is a well-established therapy for PD and considered even earlier in the course of the disease when the first clinical signs of motor fluctuations and medically refractory symptoms such as tremor appear [7][13]. DBS treatment is associated with substantial symptomatic relief and maintenance of activities of daily living even in the long-term of about 10 years [14]. The lower the preoperative quality of life (QOL), the higher the improvement in QOL after 24 months [15]. Therefore, DBS is often considered a “game changer” for both PD patients and their caregivers and raises high expectations of DBS effects on QOL. As to the great involvement of partners in caregiving, the decision to undergo DBS surgery should take into account the caregivers and patients expectations and fears. DBS represents an invasive operation of the brain with potential intraoperative complications such as intracranial bleeding, infection and the need for electrode revision [16], which might elicit fears and concerns in terms of intraoperative adverse events in patients and caregivers. Complication rates are low, but must be disclosed to the caregiver and care recipient. PD patients as well as caregiver fear the idea of “becoming another person” by DBS, so the concept of an individual identity and possible, mostly transient disease- and medication-related mood changes should be discussed prior to surgery [17][18]. One of the most important factors represent unrealistic expectations of beneficial DBS effects, since patient and caregiver might overestimate DBS effects on particular non-responsive symptom complexes as the lack of DBS effects on dopa-resistant features as freezing of gait or speech. The anticipated beneficail effects as well as potential lack of DBS effects must be disclosed to patient and caregiver, since unrealistic, unmet expectations contribute to the postoperative patient and caregiver dissatisfaction and increased CB [17].3. Postoperative Aspects of Caregiver Burden

3.1. Caregiver Burden Outcome after STN-DBS Implantation of PD Dependants

There might be several factors contributing to this incongruent development of QOL of patients and caregivers postoperatively:

1. The preexisting neuropsychiatric and medical condition of the caregivers themselves might play a role in the development of postoperative CB [19]. Higher age of the caregiver is one important mediator of postoperative CB [46][20]. The caregiver grows older along with the PD patient and might as well suffer from illnesses. Besides, the preoperative Beck DI epression Inventory (BDI) score is an important predictor of postoperative CB one year after DBS surgery [20]. Thus, the well-being of the caregiver should also be addressed in the context of their PD partners DBS surgery.

2. The postoperative extent of neuropsychiatric symptoms within PD patients significantly influences the CB of their relatives. Postoperatively, CB was shown to be associated with the patients degree of apathy and depression [19]. In PD patients and caregivers, postoperative caregiver burden was significantly related to PD patients BDI score (Beck depression inventory), caregiver-rated attentional impulsiveness of PD patients or patients hypersexuality [2].

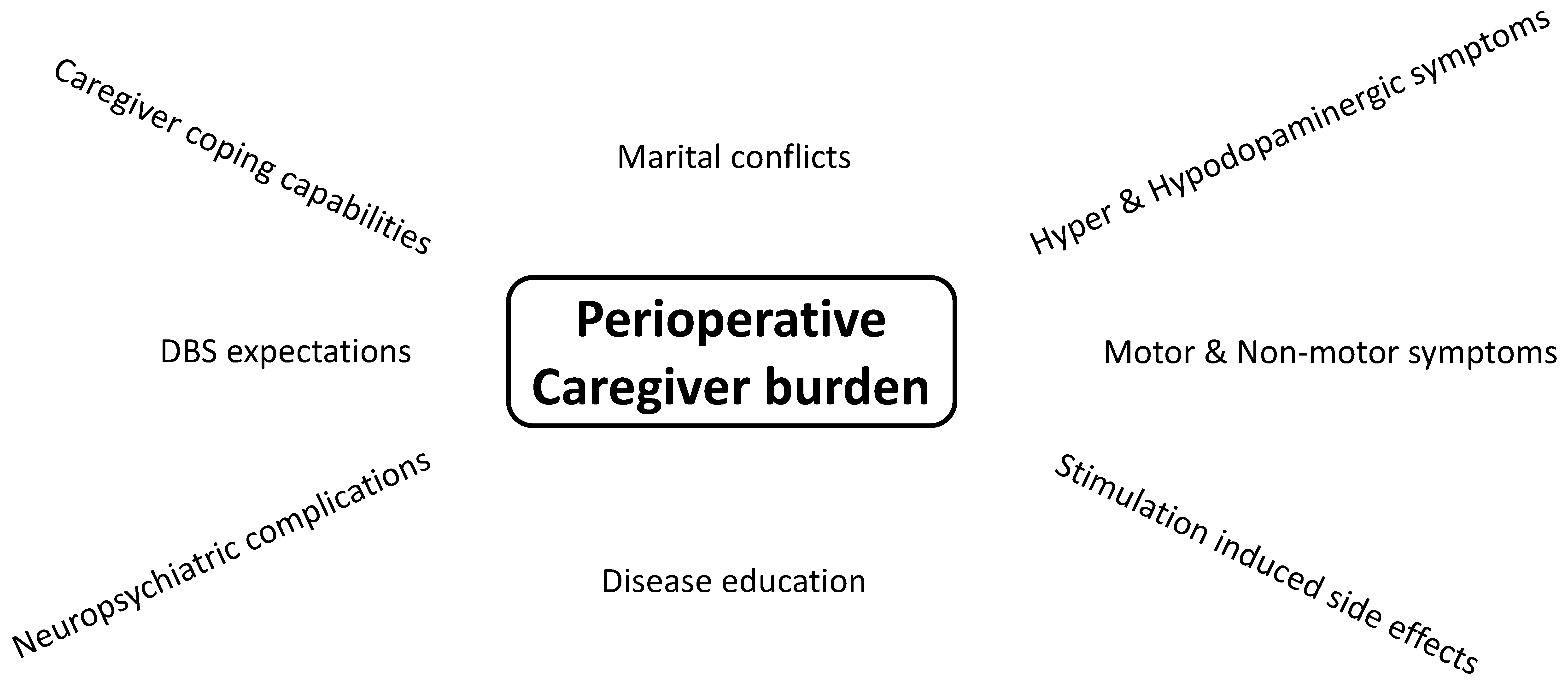

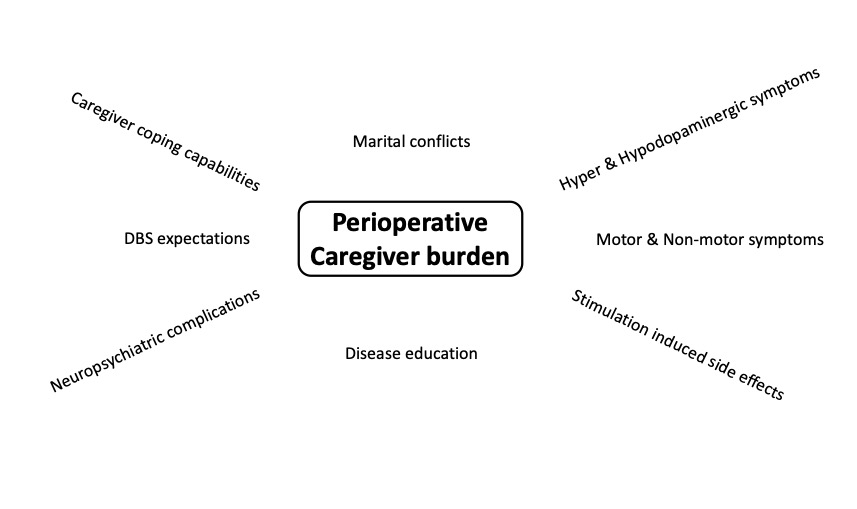

3.Postoperative marital conflicts due to changes of the relationship affect CB. DBS surgery profoundly changes caregiver responsibilities and disease-related symptoms due to the sudden relief of disability. With STN-DBS, social maladjustment as a result of the dramatic improvement of the clinical status and identity challenge can occur as part of the “burden of normality” syndrom [21]. 4. DBS is a symptomatic, but not disease-modifying therapy, thus in the long- term, disease progression with re-emergence of motor symptoms, onset of cognitive impairment and loss of autonomy of PD patients might result in re-occurrence of increased CB [22]. This might contribute to the observation that CB increases in caregivers of some PD patients within the first 2 years after STN-DBS [23]. Still, long-term observations of CB are scarce and need to be obtained in larger cohorts of long-term caregivers (Figure 1).

3.2. Caregiver Burden in Partners of PD Patients with Globus Pallidus Internus Stimulation

The globus pallidus internus (Gpi) is an alternative DBS target for PD patients beside STN implantation. The Gpi is supposed to have a lower risk of dysarthria, neuropsychiatric complications and impaired cognition [24]. The discussion of the favourable target in PD is still controversial. There is also scarce information on caregiver burden in Gpi patients [25]. In a cohort with 275 DBS patients, including PD patients implanted in both, STN and Gpi, caregiver burden measured by the Multidimensional Caregiver Strain Index (MCSI) was associated with PD patients age at surgery and interval since surgery [25]. Overall, QOL increased in these specific DBS patients, whereas CB of the relatives was not regularly improved in the longterm. CB of partners of PD patients with STN and Gpi was mostly reduced shortly after DBS implantation, but increased over time along with disease progression and reduced QOL. Further research in larger cohorts is needed on CB in caregivers of PD patients with Gpi stimulation.4. Future Caregiving Challenges

DBS research is further advancing and new promising technologies are in the pipeline. Closed-loop systems with beta oscillations as internal biomarkers for independent, self-regulated adaption of stimulation are one example of current technological developments, which might improve PD patient outcome, reduce neuropsychiatric side effects and thus could potentially decrease CB [26]. Still, these new systems might lead to increased DBS programming burden, which might be associated with increased CB. Another promising field is telemedicine with remote access for DBS programming [27]. Optimization of DBS parameters is often performed only by movement disorders specialists at specific, distant university hospitals, resulting in difficult transport and care coordination [28]. Telemedicine has already proven to reduce CB due to more flexible patient treatment and reduction of transportation issues to outpatient clinics. Telehealth with teleprogramming of DBS has become particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic with overall satisfactory patient experience [29].5. Conclusions

Informal caregivers play an important role in the daily care of PD patients before and after DBS surgery. Caregiver burden does not improve in all caregivers after STN-DBS in contrast to dramatic improvement of motor and non-motor symptoms and quality of life in PD patients. Relevant factors for postoperative CB are caregiver coping capabilities, postoperative onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms of PD patients, marital conflicts and the awareness of the symptomatic nature of DBS therapy. But, there is still a lack of information on long-term caregiver burden and predictors after STN-DBS. Potential tools to reduce postoperative CB represent “preparedness of the caregivers”, which could be protective against postoperative caregivers distress [30]. Caregivers should be informed about the specific postoperative aspect of STN-DBS and the potential effect on their own QoL. They should be more intensively integrated into the pre- and postoperative processes. Another option to reduce CB of STN-DBS patients could be cognitive behavioral therapy for caregivers [31], which could substantially modify CB prior to and after STN-DBS surgery. Additionally, self-management programs to retain social participation can help the caregiver to maintain well-being during the course of the disease [32] [33]. In summary, there are heterogeneous results on CB changes in partners of PD patients after STN-DBS or GPI-DBS, but there are therapeutic options available to reduce CB.References

- Steven Zarit; Msg Pamela A. Todd; Judy M. Zarit; Subjective Burden of Husbands and Wives as Caregivers: A Longitudinal Study. The Gerontologist 1986, 26, 260-266, 10.1093/geront/26.3.260.

- Philip E. Mosley; Rebecca Moodie; Nadeeka Dissanayaka; Caregiver Burden in Parkinson Disease: A Critical Review of Recent Literature. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 2017, 30, 235-252, 10.1177/0891988717720302.

- Geum-Bong Lee; Hyunhee Woo; Su-Yoon Lee; Sang-Myung Cheon; Jae Woo Kim; The burden of care and the understanding of disease in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217581, 10.1371/journal.pone.0217581.

- Ronald D. Adelman; Lyubov L. Tmanova; Diana Delgado; Sarah Dion; Mark S. Lachs; Caregiver Burden. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 2014, 311, 1052-1060, 10.1001/jama.2014.304.

- Franziska Thieken; Marlena van Munster; Deriving Implications for Care Delivery in Parkinson’s Disease by Co-Diagnosing Caregivers as Invisible Patients. Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 1629, 10.3390/brainsci11121629.

- Günther Deuschl; Carmen Schade-Brittinger; Paul Krack; Jens Volkmann; Helmut Schäfer; Kai Bötzel; Christine Daniels; Angela Deutschländer; Ulrich Dillmann; Wilhelm Eisner; et al.Doreen GruberWolfgang HamelJan HerzogRüdiger HilkerStephan KlebeManja KlossJan KoyMartin KrauseAndreas KupschDelia LorenzStefan LorenzlH. Maximilian MehdornJean Richard MoringlaneWolfgang OertelMarcus O. PinskerHeinz ReichmannAlexander ReussGerd-Helge SchneiderAlfons SchnitzlerUlrich SteudeVolker SturmLars TimmermannVolker TronnierThomas TrottenbergLars WojteckiElisabeth WolfWerner PoeweJürgen Voges A Randomized Trial of Deep-Brain Stimulation for Parkinson's Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2006, 355, 896-908, 10.1056/nejmoa060281.

- W.M.M. Schuepbach; J. Rau; K. Knudsen; Jens Volkmann; Paul Krack; L. Timmermann; T.D. Hälbig; H. Hesekamp; S.M. Navarro; N. Meier; et al.D. FalkM. MehdornS. PaschenM. MaaroufM.T. BarbeGereon R. FinkA. KupschD. GruberG.-H. SchneiderE. SeigneuretA. KistnerP. ChaynesF. Ory-MagneC. Brefel CourbonJ. VesperAlfons SchnitzlerL. WojteckiJ.-L. HouetoB. BatailleD. MaltêteP. DamierS. RaoulF. Sixel-DoeringD. HellwigAlireza GharabaghiRejko KrügerM.O. PinskerF. AmtageJ.-M. RégisT. WitjasS. ThoboisPatrick MertensM. KlossA. HartmannW.H. OertelB. PostH. SpeelmanY. AgidC. Schade-BrittingerGünther Deuschl Neurostimulation for Parkinson's Disease with Early Motor Complications. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 368, 610-622, 10.1056/nejmoa1205158.

- Maria Rita Lo Monaco; Enrico Di Stasio; Diego Ricciardi; Marcella Solito; Martina Petracca; Domenico Fusco; Graziano Onder; Giovanni Landi; Giuseppe Zuccalà; Rosa Liperoti; et al.Maria Camilla CiprianiCaterina BrisiRoberto BernabeiMaria Caterina SilveriAnna Rita Bentivoglio What about the caregiver? A journey into Parkinson’s disease following the burden tracks. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 2020, 33, 991-996, 10.1007/s40520-020-01600-5.

- M. Klietz; T. Schnur; S. Drexel; Florian Lange; A. Tulke; L. Rippena; L. Paracka; D. Dressler; Günter Höglinger; F. Wegner; et al. Association of Motor and Cognitive Symptoms with Health-Related Quality of Life and Caregiver Burden in a German Cohort of Advanced Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Parkinson's Disease 2020, 2020, 1-8, 10.1155/2020/5184084.

- Richard S. Henry; Sarah K. Lageman; Paul B. Perrin; The relationship between Parkinson’s disease symptoms and caregiver quality of life.. Rehabilitation Psychology 2020, 65, 137-144, 10.1037/rep0000313.

- Pablo Martinez-Martin; Carmen Rodriguez-Blazquez; Maria João Forjaz; Belén Frades-Payo; Luis Agüera-Ortiz; Daniel Weintraub; Ana Riesco; Monica M. Kurtis; K Ray Chaudhuri; Neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver's burden in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2015, 21, 629-634, 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.03.024.

- J. K. Dlay; G. W. Duncan; T. K. Khoo; C. H. Williams-Gray; D. P. Breen; R. A. Barker; D. J. Burn; R. A. Lawson; A. J. Yarnall; Progression of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms over Time in an Incident Parkinson’s Disease Cohort (ICICLE-PD). Brain Sciences 2020, 10, 78, 10.3390/brainsci10020078.

- Daniel Weiss; Jens Volkmann; Alfonso Fasano Md; Andrea Kühn; Paul Krack; Günther Deuschl; Changing Gears – DBS For Dopaminergic Desensitization in Parkinson's Disease?. Annals of Neurology 2021, 90, 699-710, 10.1002/ana.26164.

- Frederick Hitti; Ashwin G. Ramayya; Brendan J. McShane; Andrew I. Yang; Kerry A. Vaughan; Gordon H. Baltuch; Long-term outcomes following deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurosurgery 2020, 132, 205-210, 10.3171/2018.8.jns182081.

- W.M. Michael Schuepbach; Lisa Tonder; Alfons Schnitzler; Paul Krack; Joern Rau; Andreas Hartmann; Thomas D. Hälbig; Fanny Pineau; Andrea Falk; Laura Paschen; et al.Stephen PaschenJens VolkmannHaidar S. DafsariMichael T. BarbeGereon R. FinkAndrea KühnAndreas KupschGerd-H. SchneiderEric SeigneuretValerie FraixAndrea KistnerP. Patrick ChaynesFabienne Ory-MagneChristine Brefel-CourbonJan VesperLars WojteckiStéphane DerreyDavid MaltêtePhilippe DamierPascal DerkinderenFriederike Sixel-DöringClaudia TrenkwalderAlireza GharabaghiTobias WächterDaniel WeissMarcus O. PinskerJean-Marie RegisTatiana WitjasStephane ThoboisPatrick MertensKarina KnudsenCarmen Schade-BrittingerJean-Luc HouetoYves AgidMarie VidailhetLars TimmermannGünther Deuschlfor the EARLYSTIM study group Quality of life predicts outcome of deep brain stimulation in early Parkinson disease. Neurology 2019, 92, e1109-e1120, 10.1212/wnl.0000000000007037.

- Katja Engel; Torge Huckhagel; Alessandro Gulberti; Monika Pötter-Nerger; Eik Vettorazzi; Ute Hidding; Chi-Un Choe; Simone Zittel; Hanna Braaß; Peter Ludewig; et al.Miriam SchaperKara KrajewskiChristian OehlweinKatrin MittmannAndreas K. EngelChristian GerloffManfred WestphalChristian K. E. MollCarsten BuhmannJohannes A. KöppenWolfgang Hamel Towards unambiguous reporting of complications related to deep brain stimulation surgery: A retrospective single-center analysis and systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198529, 10.1371/journal.pone.0198529.

- Cassandra J. Thomson; Rebecca A. Segrave; Eric Racine; Narelle Warren; Dominic Thyagarajan; Adrian Carter; “He’s Back so I’m Not Alone”: The Impact of Deep Brain Stimulation on Personality, Self, and Relationships in Parkinson’s Disease. Qualitative Health Research 2020, 30, 2217-2233, 10.1177/1049732320951144.

- Karsten Witt; Jens Kuhn; Lars Timmermann; Mateusz Zurowski; Christiane Woopen; Deep Brain Stimulation and the Search for Identity. Neuroethics 2011, 6, 499-511, 10.1007/s12152-011-9100-1.

- Catharine J. Lewis; Franziska Maier; Nina Horstkötter; Carsten Eggers; Veerle Visser-Vandewalle; Elena Moro; Mateusz Zurowski; Jens Kuhn; Christiane Woopen; Lars Timmermann; et al. The impact of subthalamic deep brain stimulation on caregivers of Parkinson’s disease patients: an exploratory study. Journal of Neurology 2014, 262, 337-345, 10.1007/s00415-014-7571-9.

- Marle M. van Hienen; Maria Fiorella Contarino; Huub A.M. Middelkoop; Jacobus J. van Hilten; Victor J. Geraedts; Effect of deep brain stimulation on caregivers of patients with Parkinson's disease: A systematic review. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2020, 81, 20-27, 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.09.038.

- Joao Flores Alves Dos Santos; Sophie Tezenas du Montcel; Marcela Gargiulo; Cecile Behar; Sébastien Montel; Thierry Hergueta; Soledad Navarro; Hayat Belaid; Pauline Cloitre; Carine Karachi; et al.Luc MalletMarie-Laure Welter Tackling psychosocial maladjustment in Parkinson’s disease patients following subthalamic deep-brain stimulation: A randomised clinical trial. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0174512, 10.1371/journal.pone.0174512.

- Radu Constantinescu; Barbro Eriksson; Yvonne Jansson; Bo Johnels; Björn Holmberg; Thordis Gudmundsdottir; Annika Renck; Peter Berglund; Filip Bergquist; Key clinical milestones 15 years and onwards after DBS-STN surgery—A retrospective analysis of patients that underwent surgery between 1993 and 2001. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2017, 154, 43-48, 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.01.010.

- Eric Jackowiak; Amanda Cook Maher; Carol Persad; Vikas Kotagal; Kara Wyant; Amelia Heston; Parag G. Patil; Kelvin L. Chou; Caregiver burden worsens in the second year after subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2020, 78, 4-8, 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.06.036.

- M. Lenard Lachenmayer; Melina Mürset; Nicolas Antih; Ines Debove; Julia Muellner; Maëlys Bompart; Janine-Ai Schlaeppi; Andreas Nowacki; Hana You; Joan P. Michelis; et al.Alain DransartClaudio PolloGuenther DeuschlPaul Krack Subthalamic and pallidal deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease—meta-analysis of outcomes. npj Parkinson's Disease 2021, 7, 1-10, 10.1038/s41531-021-00223-5.

- Genko Oyama; Michael S. Okun; Peter Schmidt; Alexander I. Tröster; John Nutt; Criscely L. Go; Kelly D. Foote; Irene A. Malaty; Deep Brain Stimulation May Improve Quality of Life in People With Parkinson’s Disease Without Affecting Caregiver Burden. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface 2014, 17, 126-132, 10.1111/ner.12097.

- Walid Bouthour; Pierre Mégevand; John Donoghue; Christian Lüscher; Niels Birbaumer; Paul Krack; Biomarkers for closed-loop deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease and beyond. Nature Reviews Neurology 2019, 15, 343-352, 10.1038/s41582-019-0166-4.

- Vibhash D. Sharma; Delaram Safarpour; Shyamal H. Mehta; Nora Vanegas-Arroyave; Daniel Weiss; Jeffrey W. Cooney; Zoltan Mari; Alfonso Fasano; Telemedicine and Deep brain stimulation - Current practices and recommendations. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2021, 89, 199-205, 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2021.07.001.

- Angelika D. van Halteren; Marten Munneke; Eva Smit; Sue Thomas; Bastiaan R. Bloem; Sirwan K. L. Darweesh; Personalized Care Management for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Parkinson's Disease 2020, 10, S11-S20, 10.3233/JPD-202126.

- Robin Van Den Bergh; Bastiaan R. Bloem; Marjan J. Meinders; Luc J.W. Evers; The state of telemedicine for persons with Parkinson's disease. Current Opinion in Neurology 2021, Publish Ah, 589-597, 10.1097/wco.0000000000000953.

- Patricia G. Archbold; Barbara J. Stewart; Merwyn R. Greenlick; Theresa Harvath; Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing & Health 1990, 13, 375-384, 10.1002/nur.4770130605.

- Philip E. Mosley; Katherine Robinson; Nadeeka N. Dissanayaka; Terry Coyne; Peter Silburn; Rodney Marsh; Deidre Pye; A Pilot Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Caregivers After Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson's Disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 2020, 34, 454-465, 10.1177/0891988720924720.

- Sue Berger; Tiffany Chen; Jenna Eldridge; Cathi A. Thomas; Barbara Habermann; Linda Tickle-Degnen; The self-management balancing act of spousal care partners in the case of Parkinson’s disease. Disability and Rehabilitation 2017, 41, 887-895, 10.1080/09638288.2017.1413427.

- Carina Hellqvist; Nil Dizdar; Peter Hagell; Carina Berterö; Märta Sund-Levander; Improving self-management for persons with Parkinson's disease through education focusing on management of daily life: Patients’ and relatives’ experience of the Swedish National Parkinson School. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2018, 27, 3719-3728, 10.1111/jocn.14522.

- Robin Van Den Bergh; Bastiaan R. Bloem; Marjan J. Meinders; Luc J.W. Evers; The state of telemedicine for persons with Parkinson's disease. Current Opinion in Neurology 2021, Publish Ah, 589-597, 10.1097/wco.0000000000000953.

- Patricia G. Archbold; Barbara J. Stewart; Merwyn R. Greenlick; Theresa Harvath; Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing & Health 1990, 13, 375-384, 10.1002/nur.4770130605.

- Sue Berger; Tiffany Chen; Jenna Eldridge; Cathi A. Thomas; Barbara Habermann; Linda Tickle-Degnen; The self-management balancing act of spousal care partners in the case of Parkinson’s disease. Disability and Rehabilitation 2017, 41, 887-895, 10.1080/09638288.2017.1413427.

- Carina Hellqvist; Nil Dizdar; Peter Hagell; Carina Berterö; Märta Sund-Levander; Improving self-management for persons with Parkinson's disease through education focusing on management of daily life: Patients’ and relatives’ experience of the Swedish National Parkinson School. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2018, 27, 3719-3728, 10.1111/jocn.14522.

- Philip E. Mosley; Katherine Robinson; Nadeeka N. Dissanayaka; Terry Coyne; Peter Silburn; Rodney Marsh; Deidre Pye; A Pilot Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Caregivers After Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson's Disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 2020, 34, 454-465, 10.1177/0891988720924720.