Virus-like particles (VLPs) are a versatile, safe, and highly immunogenic vaccine platform. The use of a very flexible vaccine platform in COVID-19 vaccine development is an important feature that cannot be ignored. Incorporating the spike protein and its variations into VLP vaccines is a desirable strategy as the morphology and size of VLPs allows for better presentation of several different antigens.

- virus-like particles

- vaccines

- COVID-19

- SARS-CoV-2

1. Introduction

| Name | Platform | Adjuvant | Dosage | Efficacy * | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronavac (Sinovac) |

Inactivated | Alum | 2 doses | 83.5% (95% CI, 65.4–92.1) | [8][9][10][11] |

| BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm) |

Inactivated | Alum | 2 doses | 72.8% (95% CI, 58.1–82.4) | [12][13] |

| BBV152-Covaxin (Bharat Biotech) |

Inactivated | Alum | 2 doses | 77.8% (95% CI, 65.2–86.4) | [14][15] |

| AZD1222–Vaxzevria (Oxford/AstraZeneca) |

Viral vector | No | 2 doses | 74.0% (95% CI, 65.3–80.5) | [16][17][18] |

| Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation) |

Viral vector | No | 2 doses | 74.0% (95% CI, 65.3–80.5) | [16][17][18] |

| Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson &Johnson-Janssen) |

Viral vector | No | 1 dose | 66.9% (95% CI, 59.0–73.4) | [19][20][21][22] |

| mRNA-1273 (Moderna) |

mRNA | No | 2 doses | 94.1% (95% CI, 89.3–96.8) | [23][24] |

| BNT162b-Comirnaty (Pfizer/BioNTech) |

mRNA | No | 2 doses | 95% (95% CI, 90.3–97.6) | [25][26] |

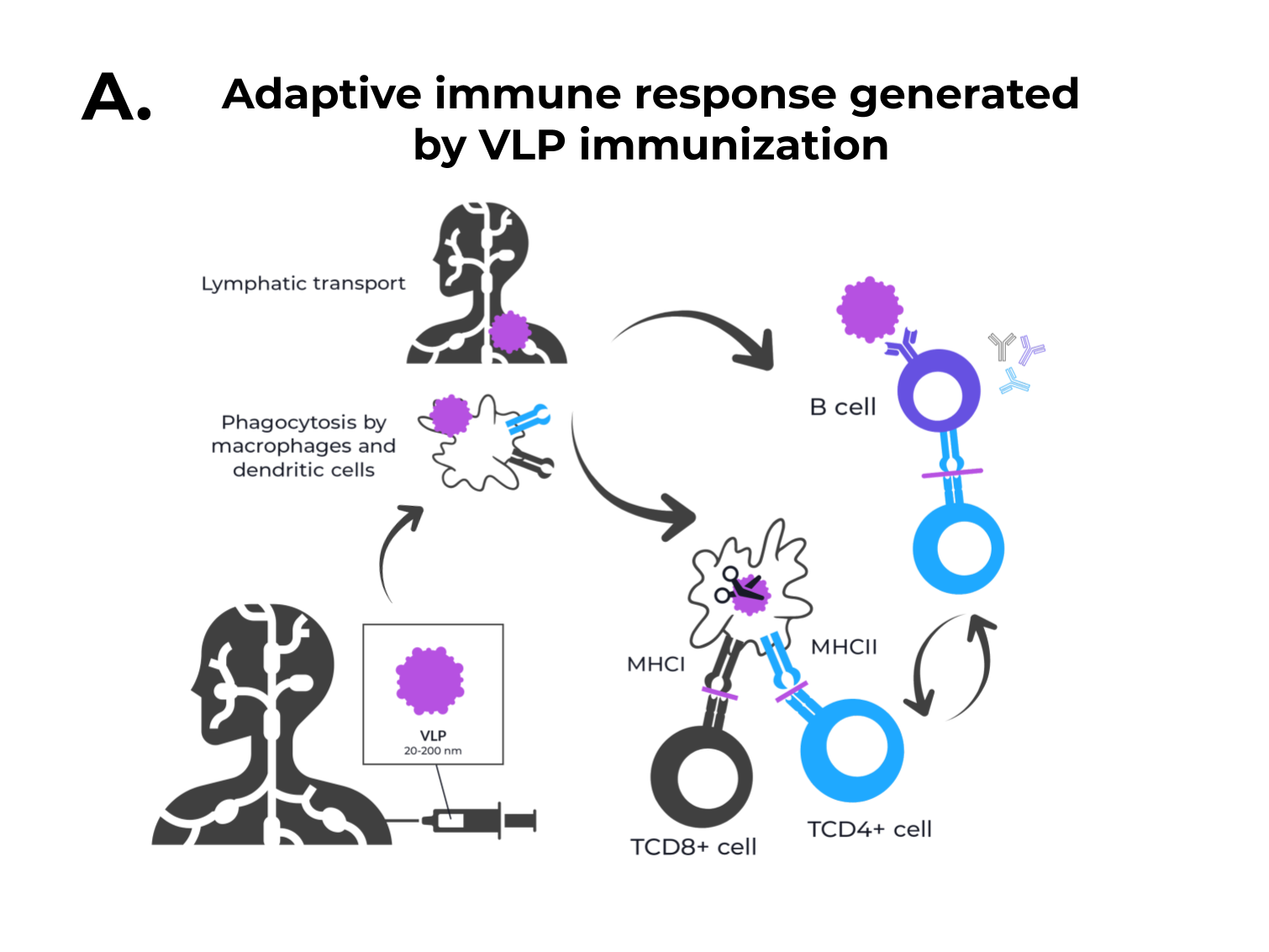

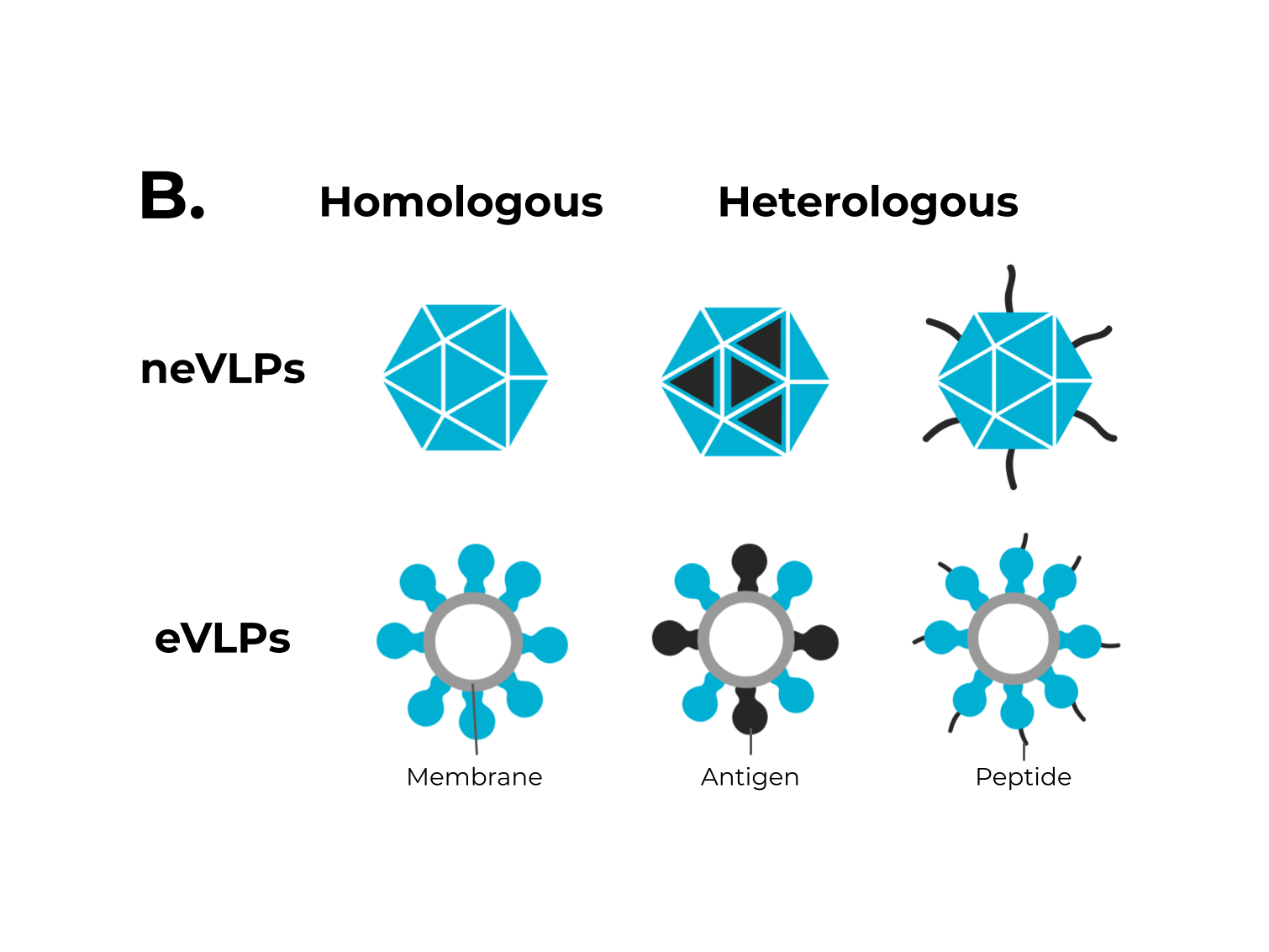

Figure 1. The adaptive immune response generated by VLPs immunization and VLPs classification. (A) After immunization, VLPs are phagocytized by dendritic cells or macrophages. Then, they are carried out to lymphatic vessels, where the antigenic regions will be processed and presented by class II MHC molecules (CD4+ T cells) and, through cross-presentation, by class I (CD8+ T cells). Immunological pathway activation by immunization with VLPs will activate robust cellular (cytokines) and humoral (B cell-antibodies) immune responses. (B) VLPs are classified as nonenveloped (neVLPs) or enveloped VLPs (eVLPs) based on the absence or presence of a lipidic membrane, respectively. These particles can also be classified as homologous or heterologous VLPs according to their composition. Homologous VLPs are assembled using proteins from the native pathogen only (blue), and heterologous VLPs can be assembled using proteins or peptides from different sources (black and blue).

Figure 1. The adaptive immune response generated by VLPs immunization and VLPs classification. (A) After immunization, VLPs are phagocytized by dendritic cells or macrophages. Then, they are carried out to lymphatic vessels, where the antigenic regions will be processed and presented by class II MHC molecules (CD4+ T cells) and, through cross-presentation, by class I (CD8+ T cells). Immunological pathway activation by immunization with VLPs will activate robust cellular (cytokines) and humoral (B cell-antibodies) immune responses. (B) VLPs are classified as nonenveloped (neVLPs) or enveloped VLPs (eVLPs) based on the absence or presence of a lipidic membrane, respectively. These particles can also be classified as homologous or heterologous VLPs according to their composition. Homologous VLPs are assembled using proteins from the native pathogen only (blue), and heterologous VLPs can be assembled using proteins or peptides from different sources (black and blue).2. SARS-CoV-2, VOCs, and Structural Vaccinology

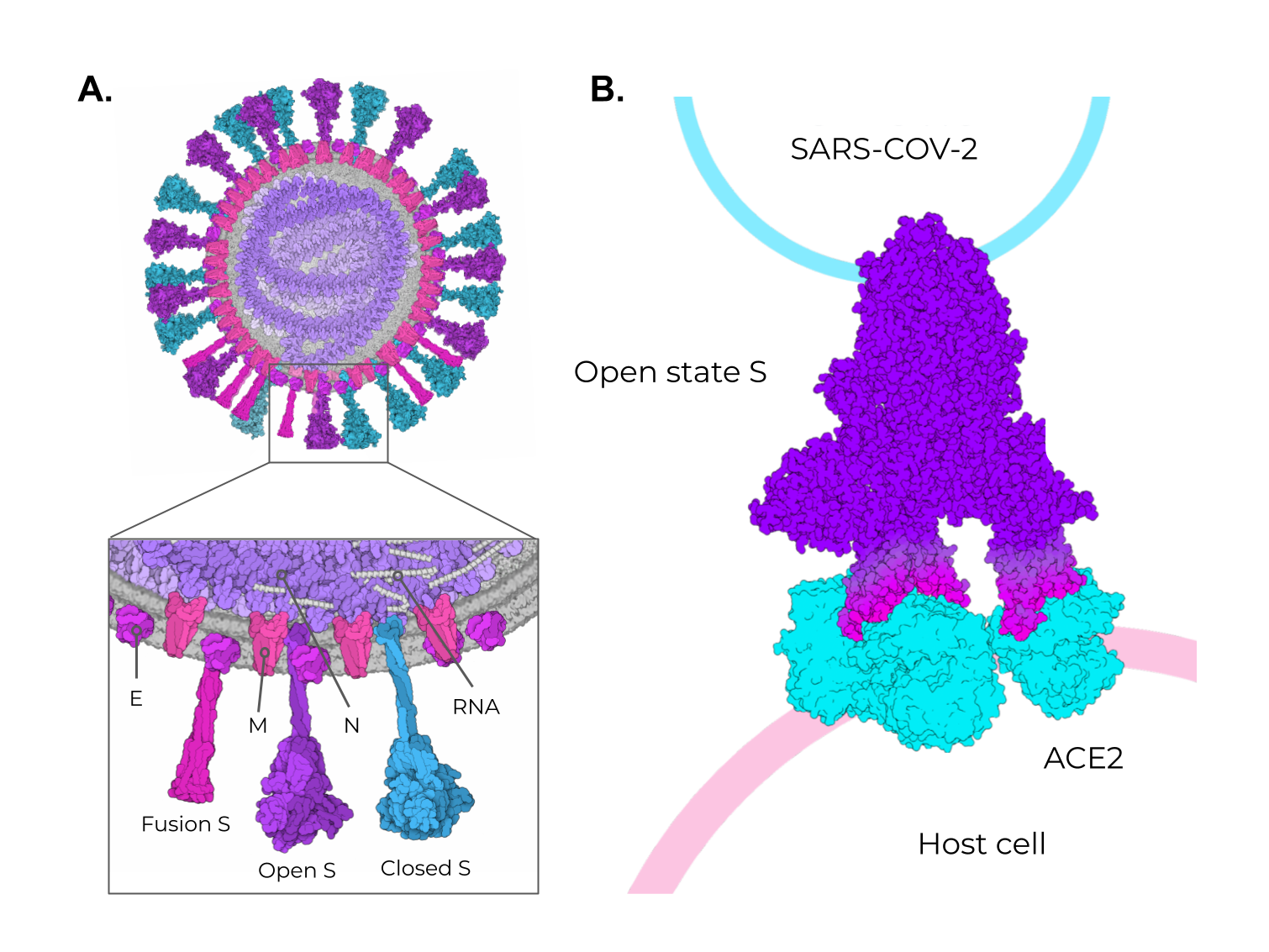

The SARS-CoV-2 positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome (29 kb in length) encodes four structural and 16 non-structural proteins [3]. The structural proteins are the membrane (M), envelope (E), spike (S), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins, as seen in other coronaviruses (Figure 2A). Figure 2. SARS-CoV-2 structural proteins and the different states of the Spike protein. (A) Schematic representation of the SARS-CoV-2 viral particle. The structure of the SARS-CoV-2 viral particle is composed of four structural proteins: Membrane (M), Envelope (E), Nucleocapsid (N), and Spike (S). The S protein is found in two different states on viral particles: open state (minor population) and closed state (major population). In addition, during the membrane fusion process (host cell entry), the S protein can be found in the fusion state (fusion S). (B) Schematic representation of the binding of open-state S (PDB ID 7498) to the ACE2 receptor present in the host cell. The illustrations were made in free software (CellPaint 2.0 [47] [91] and 3D Protein Imager [48][92]). The binding figure was made using the crystal structure of ACE2 bound to Spike available at the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 7A98).

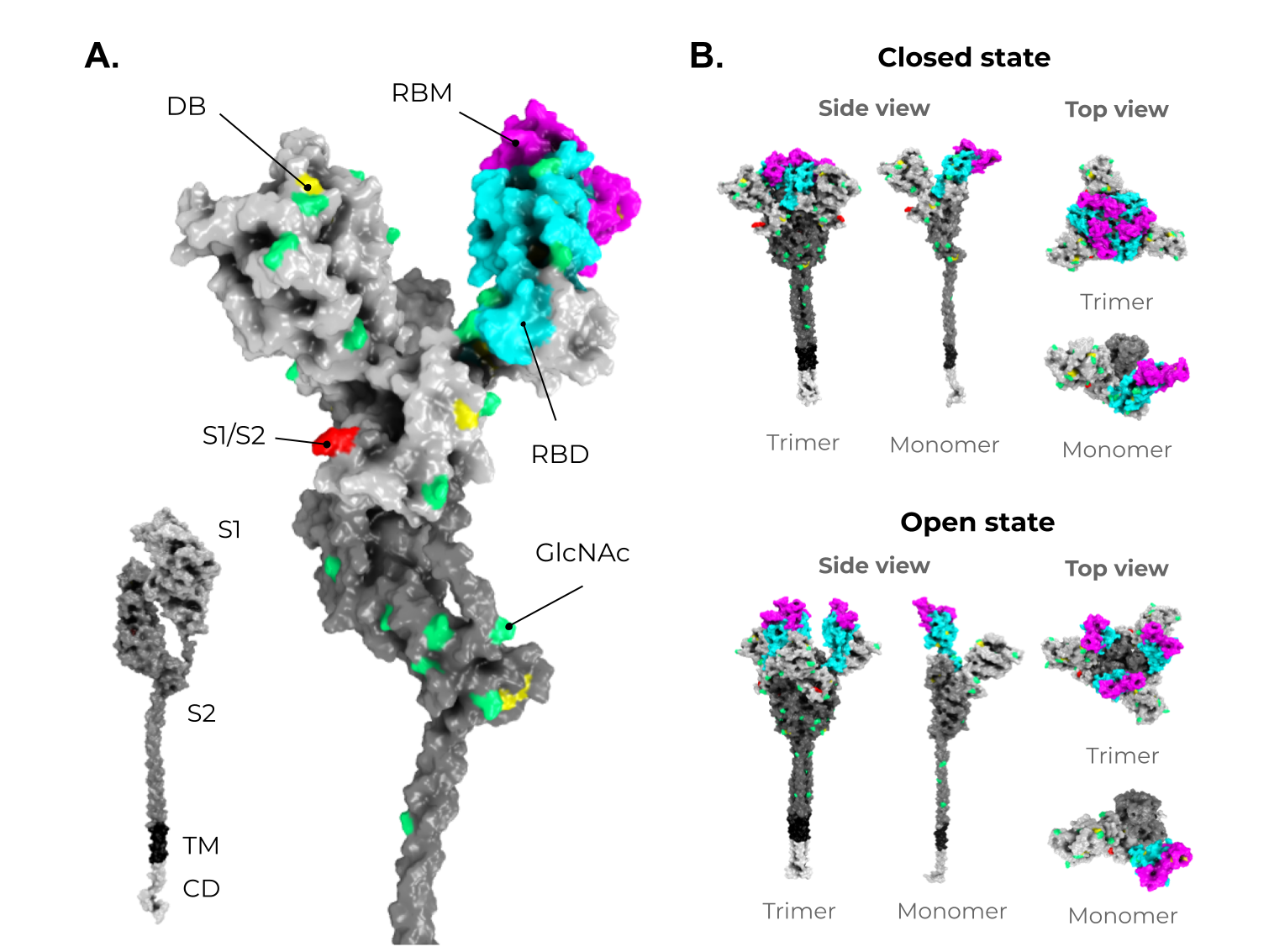

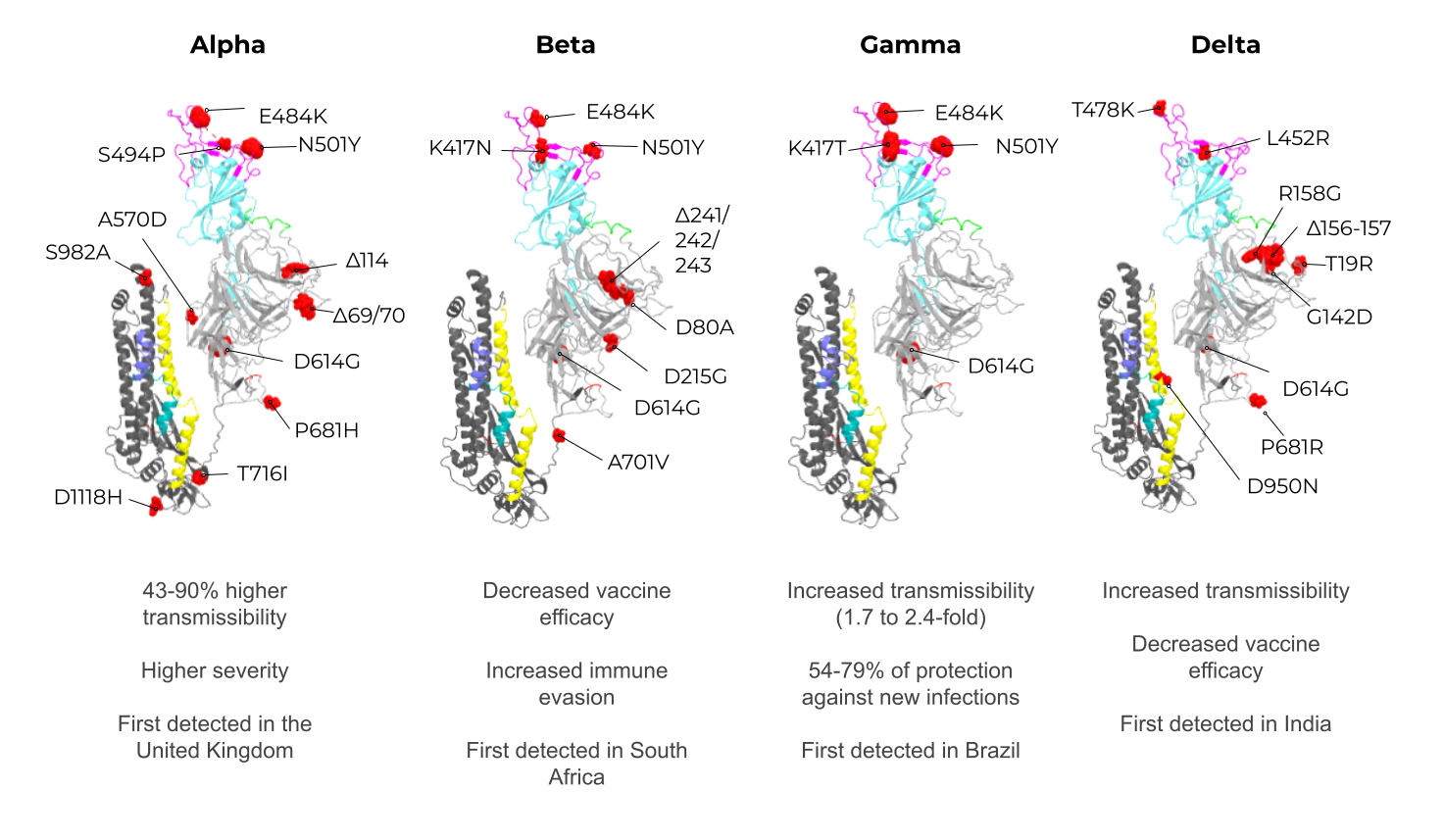

Among these structural proteins, the main target for vaccine development is the SARS-CoV-2 S protein, which gives the characteristic crown-shaped structure of coronaviruses [4947][5048]. S is a highly glycosylated [5149] homotrimer transmembrane protein (UNIPROT ID P0DTC2) composed of 1273 amino acids per chain. Known human sarbecoviruses (SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-1) and the alphacoronavirus NL63 invade the host cell through an interaction between the S protein and its receptor, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [49][50][51][52][53][54][55] (Figure 2B). In general, the S protein consists of two major regions in addition to the signal peptide (SP) (1–12): the S1 subunit (13–685), and the S2 subunit (686–1273), which contains the transmembrane region (TM) (1214–1234) followed by the cytoplasmic domain (CD) (1235–1273) (Figure 3A). The S protein and the ACE2 receptor binding are mediated by the receptor-binding motif (RBM; 437–508), located in the receptor-binding domain (RBD; 319–541) [5654] (Figure 3A, purple and cyan, respectively). The fusion machinery in S2 is composed of two fusion peptides (816–837 and 835–855) and two heptad regions (920–970 and 1163–1202). The first site of cleavage targeted by host proteases, such as furin and TMPRSS2, is located in the S1/S2 interface (685–686) [5755][5856][5957] (Figure 3A, red). Removing the S1/S2 site promotes conformational changes that open the second cleavage site at S2 (815–816). The subsequent cleavage of the S2 site promotes the projection of needle-shaped fusion peptides into the host membrane [6058][6159], leading to cell fusion in 60–120 s in feline coronavirus [6260]. The S protein presents a closed and open conformation [45][6361] (Figure 3B, upper and bottom panel, respectively). With one or more RBDs projected outward, the open state constitutes the major conformation population of viable virions [6361]. The increased exposure and steric freedom enable stronger interactions with the ACE2 receptor [45][6462]. Therefore, mutations that stabilize this open conformation lead to positive selection, making the virus more transmissible [6563][6664][6765].

Figure 2. SARS-CoV-2 structural proteins and the different states of the Spike protein. (A) Schematic representation of the SARS-CoV-2 viral particle. The structure of the SARS-CoV-2 viral particle is composed of four structural proteins: Membrane (M), Envelope (E), Nucleocapsid (N), and Spike (S). The S protein is found in two different states on viral particles: open state (minor population) and closed state (major population). In addition, during the membrane fusion process (host cell entry), the S protein can be found in the fusion state (fusion S). (B) Schematic representation of the binding of open-state S (PDB ID 7498) to the ACE2 receptor present in the host cell. The illustrations were made in free software (CellPaint 2.0 [47] [91] and 3D Protein Imager [48][92]). The binding figure was made using the crystal structure of ACE2 bound to Spike available at the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 7A98).

Among these structural proteins, the main target for vaccine development is the SARS-CoV-2 S protein, which gives the characteristic crown-shaped structure of coronaviruses [4947][5048]. S is a highly glycosylated [5149] homotrimer transmembrane protein (UNIPROT ID P0DTC2) composed of 1273 amino acids per chain. Known human sarbecoviruses (SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-1) and the alphacoronavirus NL63 invade the host cell through an interaction between the S protein and its receptor, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [49][50][51][52][53][54][55] (Figure 2B). In general, the S protein consists of two major regions in addition to the signal peptide (SP) (1–12): the S1 subunit (13–685), and the S2 subunit (686–1273), which contains the transmembrane region (TM) (1214–1234) followed by the cytoplasmic domain (CD) (1235–1273) (Figure 3A). The S protein and the ACE2 receptor binding are mediated by the receptor-binding motif (RBM; 437–508), located in the receptor-binding domain (RBD; 319–541) [5654] (Figure 3A, purple and cyan, respectively). The fusion machinery in S2 is composed of two fusion peptides (816–837 and 835–855) and two heptad regions (920–970 and 1163–1202). The first site of cleavage targeted by host proteases, such as furin and TMPRSS2, is located in the S1/S2 interface (685–686) [5755][5856][5957] (Figure 3A, red). Removing the S1/S2 site promotes conformational changes that open the second cleavage site at S2 (815–816). The subsequent cleavage of the S2 site promotes the projection of needle-shaped fusion peptides into the host membrane [6058][6159], leading to cell fusion in 60–120 s in feline coronavirus [6260]. The S protein presents a closed and open conformation [45][6361] (Figure 3B, upper and bottom panel, respectively). With one or more RBDs projected outward, the open state constitutes the major conformation population of viable virions [6361]. The increased exposure and steric freedom enable stronger interactions with the ACE2 receptor [45][6462]. Therefore, mutations that stabilize this open conformation lead to positive selection, making the virus more transmissible [6563][6664][6765].

Figure 3. Structure and domain organization of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein. (A) The S structure comprises a cytoplasmic domain (CD, white), a transmembrane domain (TM, black), and an ectodomain, which is divided into two subunits, S1 (gray) and S2 (dark gray). The magnification shows the several disulfide bridges (DB, yellow) and the glycosylation sites (GlcNAc, green) through the S protein ectodomain. It is highlighted in red, the S1/S2 interface. The receptor-binding domain (RBD, in cyan) and the receptor-binding motif (RBM, magenta) are also shown in S1. (B) As mentioned in Figure 2, the S protein shows two conformers on viable viruses (closed and open state). The upper panel shows the S protein in the closed state (trimeric and monomeric state). The bottom panel shows the S protein in the open state (trimeric and monomeric state). Illustrations were made in PyMol [68][110] using the wild-type structures available from Zhang et al. [69][70][107,111].

Figure 3. Structure and domain organization of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein. (A) The S structure comprises a cytoplasmic domain (CD, white), a transmembrane domain (TM, black), and an ectodomain, which is divided into two subunits, S1 (gray) and S2 (dark gray). The magnification shows the several disulfide bridges (DB, yellow) and the glycosylation sites (GlcNAc, green) through the S protein ectodomain. It is highlighted in red, the S1/S2 interface. The receptor-binding domain (RBD, in cyan) and the receptor-binding motif (RBM, magenta) are also shown in S1. (B) As mentioned in Figure 2, the S protein shows two conformers on viable viruses (closed and open state). The upper panel shows the S protein in the closed state (trimeric and monomeric state). The bottom panel shows the S protein in the open state (trimeric and monomeric state). Illustrations were made in PyMol [68][110] using the wild-type structures available from Zhang et al. [69][70][107,111].

3. Enveloped VLPs against SARS-CoV-2

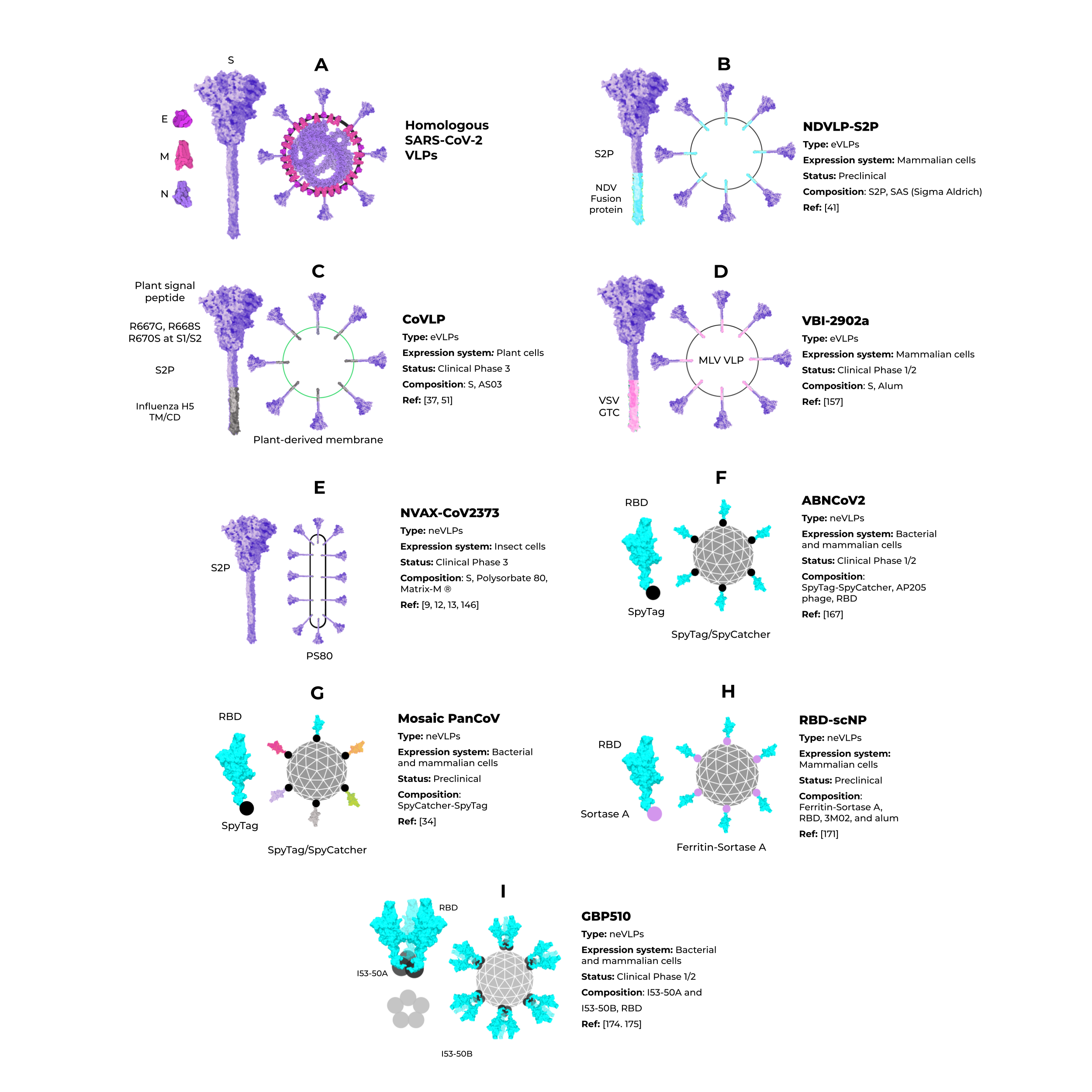

Some studies have shown that the minimal requirement for the assembly of SARS-CoV-2 VLPs and other coronaviruses is the combination of M and either the E or N proteins. However, most particles include the N protein and the highly immunogenic S protein for better assembly and expression (Figure 5A) [7469][7570]. To date, Vero E6 cells presented the highest expression of S-containing VLPs when compared to HEK293 cells [7570]. All of these initial approaches for SARS-CoV-2 VLP production show a promising use of this platform in vaccine development. However, industrial viability and large-scale production were not considered, and these are crucial features for further development and are still very challenging in the eVLP production field [5856].

Although homologous VLPs are an attractive strategy for producing these particles, the combination of antigenic SARS-CoV-2 proteins with other highly expressed heterologous proteins (that could be used as alternative VLPs scaffolds) are an exciting strategy to address issues of industrial production. The NDVLP-S2P (Figure 5B) is a heterologous chimeric eVLP vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2 that uses the structure of a well-characterized enveloped virus, the Newcastle disease virus (NDV) [41], and is being developed by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). The transmembrane domain of the NDV fusion protein was fused to SARS-CoV-2 S2P, allowing the correct display of S2P on the VLP surface [41][45][7671]. The NDV-S2P VLPs were more immunogenic than the trimeric S protein alone, showing that the presentation of antigens on the surface of the VLPs is advantageous [41]. Another heterologous SARS-CoV-2 eVLPs vaccine candidate is the CoVLP from Medicago/GSK (Figure 5C) [37][7772]. This vaccine is based on VLPs that display a mutated S2P protein, which comprises a plant signal peptide, GSAS substitutions in the S1/S2 site, and TM/CD regions of the Influenza H5 A/Indonesia/5/2005. The CoVLP vaccine is formulated with AS03 [7873] and given in a two-dose regimen. After the second dose, immunized volunteers showed higher serum SARS-CoV-2 nAb titers than in convalescent plasma. This vaccine candidate is already in phase 3 clinical trials (NCT04636697). VBI-2902a [7671] is an MLV-based eVLPs vaccine candidate containing the S protein in the prefusion state fused with the VSV-G transmembrane cytoplasmic domain (VSV-GTC) (Figure 5D). This vaccine is being developed by VBI Vaccines and is in ongoing clinical trials 1/2 (NCT04773665).

Figure 5. Enveloped and nonenveloped VLPs against SARS-CoV-2.

4. Non-Enveloped VLPs against SARS-CoV-2

Unlike eVLPs, neVLPs do not contain any lipid membranes. They can be produced in simpler expression systems, such as those using bacteria (i.e., Escherichia coli) and yeast (i.e., Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia Pastoris) cells. The Hepatitis B virus vaccine, Engerix-B® [7974], and the Human papillomavirus vaccine, Gardasil® and Gardasil 9® [33], are neVLPs-based vaccines approved by the FDA. They are produced in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, an efficient expression system that is industrially scalable and cheaper than mammalian and insect cell systems. Despite these clear advantages, bacteria and yeast cells lack complex post-translational modifications (PTM) needed to produce some proteins, such as the highly glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 S protein [8075][8176]. Thus, the choice of the best expression system could be a determinant for protein/VLP production, even considering neVLPs. Cervarix® is another HPV neVLP-based vaccine [8277] that is highly immunogenic [8378] and effective [8479][8580] against HPV types 16 and 18, which are the main serotypes that cause cervical cancer [8681]. The Cervarix® vaccine is produced using insect cells infected with recombinant baculovirus [40][8782][8883].

5. Conclusions

References

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733.

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated with a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273.

- Lu, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Niu, P.; Yang, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Huang, B.; Zhu, N.; et al. Genomic Characterisation and Epidemiology of 2019 Novel Coronavirus: Implications for Virus Origins and Receptor Binding. Lancet 2020, 395, 565–574.

- Weekly Epidemiological Update on COVID-19—22 June 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---22-june-2021 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Li, Y.; Tenchov, R.; Smoot, J.; Liu, C.; Watkins, S.; Zhou, Q. A Comprehensive Review of the Global Efforts on COVID-19 Vaccine Development. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 512–533.

- WHO Issues Emergency Use Listing for Eighth COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/03-11-2021-who-issues-emergency-use-listing-for-eighth-covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 7 November 2021).

- COVID-19 Vaccines. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 7 November 2021).

- Gao, Q.; Bao, L.; Mao, H.; Wang, L.; Xu, K.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, N.; Lv, Z.; et al. Development of an Inactivated Vaccine Candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020, 369, 77–81.

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, G.; Pan, H.; Li, C.; Hu, Y.; Chu, K.; Han, W.; Chen, Z.; Tang, R.; Yin, W.; et al. Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of an Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Healthy Adults Aged 18–59 Years: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 181–192.

- Bueno, S.M.; Abarca, K.; González, P.A.; Gálvez, N.M.; Soto, J.A.; Duarte, L.F.; Schultz, B.M.; Pacheco, G.A.; González, L.A.; Vázquez, Y.; et al. Interim Report: Safety and Immunogenicity of an Inactivated Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in Healthy Chilean Adults in a Phase 3 Clinical Trial. medRxiv 2021.

- Tanriover, M.D.; Doğanay, H.L.; Akova, M.; Güner, H.R.; Azap, A.; Akhan, S.; Köse, Ş.; Erdinç, F.Ş.; Akalın, E.H.; Tabak, Ö.F.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of an Inactivated Whole-Virion SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine (CoronaVac): Interim Results of a Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial in Turkey. Lancet 2021, 398, 213–222.

- Xia, S.; Duan, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Z.; Li, X.; Peng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Effect of an Inactivated Vaccine Against SARS-CoV-2 on Safety and Immunogenicity Outcomes: Interim Analysis of 2 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA 2020, 324, 951–960.

- Al Kaabi, N.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, S.; Yang, Y.; Al Qahtani, M.M.; Abdulrazzaq, N.; Al Nusair, M.; Hassany, M.; Jawad, J.S.; Abdalla, J.; et al. Effect of 2 Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines on Symptomatic COVID-19 Infection in Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 326, 35–45.

- Ella, R.; Reddy, S.; Blackwelder, W.; Potdar, V.; Yadav, P.; Sarangi, V.; Aileni, V.K.; Kanungo, S.; Rai, S.; Reddy, P.; et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Lot to Lot Immunogenicity of an Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine (BBV152): A, Double-Blind, Randomised, Controlled Phase 3 Trial. medRxiv 2021.

- Ella, R.; Vadrevu, K.M.; Jogdand, H.; Prasad, S.; Reddy, S.; Sarangi, V.; Ganneru, B.; Sapkal, G.; Yadav, P.; Abraham, P.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of an Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine, BBV152: A Double-Blind, Randomised, Phase 1 Trial. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 637–646.

- Folegatti, P.M.; Ewer, K.J.; Aley, P.K.; Angus, B.; Becker, S.; Belij-Rammerstorfer, S.; Bellamy, D.; Bibi, S.; Bittaye, M.; Clutterbuck, E.A.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 NCoV-19 Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: A Preliminary Report of a Phase 1/2, Single-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 467–478.

- Falsey, A.R.; Sobieszczyk, M.E.; Hirsch, I.; Sproule, S.; Robb, M.L.; Corey, L.; Neuzil, K.M.; Hahn, W.; Hunt, J.; Mulligan, M.J.; et al. Phase 3 Safety and Efficacy of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 NCoV-19) COVID-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021.

- Voysey, M.; Clemens, S.A.C.; Madhi, S.A.; Weckx, L.Y.; Folegatti, P.M.; Aley, P.K.; Angus, B.; Baillie, V.L.; Barnabas, S.L.; Bhorat, Q.E.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 NCoV-19 Vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: An Interim Analysis of Four Randomised Controlled Trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet 2021, 397, 99–111.

- Sadoff, J.; Le Gars, M.; Shukarev, G.; Heerwegh, D.; Truyers, C.; de Groot, A.M.; Stoop, J.; Tete, S.; Van Damme, W.; Leroux-Roels, I.; et al. Interim Results of a Phase 1–2a Trial of Ad26.COV2.S COVID-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1824–1835.

- Bos, R.; Rutten, L.; van der Lubbe, J.E.M.; Bakkers, M.J.G.; Hardenberg, G.; Wegmann, F.; Zuijdgeest, D.; de Wilde, A.H.; Koornneef, A.; Verwilligen, A.; et al. Ad26 Vector-Based COVID-19 Vaccine Encoding a Prefusion-Stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spike Immunogen Induces Potent Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5, 1–11.

- Mercado, N.B.; Zahn, R.; Wegmann, F.; Loos, C.; Chandrashekar, A.; Yu, J.; Liu, J.; Peter, L.; McMahan, K.; Tostanoski, L.H.; et al. Single-Shot Ad26 Vaccine Protects against SARS-CoV-2 in Rhesus Macaques. Nature 2020, 586, 583–588.

- Sadoff, J.; Gray, G.; Vandebosch, A.; Cárdenas, V.; Shukarev, G.; Grinsztejn, B.; Goepfert, P.A.; Truyers, C.; Fennema, H.; Spiessens, B.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Single-Dose Ad26.COV2.S Vaccine against COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2187–2201.

- Anderson, E.J.; Rouphael, N.G.; Widge, A.T.; Jackson, L.A.; Roberts, P.C.; Makhene, M.; Chappell, J.D.; Denison, M.R.; Stevens, L.J.; Pruijssers, A.J.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 MRNA-1273 Vaccine in Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2427–2438.

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the MRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 403–416.

- Walsh, E.E.; Frenck, R.W.; Falsey, A.R.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Neuzil, K.; Mulligan, M.J.; Bailey, R.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of Two RNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccine Candidates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2439–2450.

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 MRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615.

- Mohsen, M.O.; Augusto, G.; Bachmann, M.F. The 3Ds in Virus-like Particle Based-vaccines: “Design, Delivery and Dynamics”. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 296, 155–168.

- Bachmann, M.; Rohrer, U.; Kundig, T.; Burki, K.; Hengartner, H.; Zinkernagel, R. The Influence of Antigen Organization on B Cell Responsiveness. Science 1993, 262, 1448–1451.

- Cubas, R.; Zhang, S.; Kwon, S.; Sevick-Muraca, E.M.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Yao, Q. Virus-like Particle (VLP) Lymphatic Trafficking and Immune Response Generation After Immunization by Different Routes. J. Immunother. 2009, 32, 118–128.

- Mohsen, M.; Gomes, A.; Vogel, M.; Bachmann, M. Interaction of Viral Capsid-Derived Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) with the Innate Immune System. Vaccines 2018, 6, 37.

- Win, S.J.; Ward, V.K.; Dunbar, P.R.; Young, S.L.; Baird, M.A. Cross-presentation of Epitopes on Virus-like Particles via the MHC I Receptor Recycling Pathway. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011, 89, 681–688.

- Bangaru, S.; Ozorowski, G.; Turner, H.L.; Antanasijevic, A.; Huang, D.; Wang, X.; Torres, J.L.; Diedrich, J.K.; Tian, J.-H.; Portnoff, A.D.; et al. Structural Analysis of Full-Length SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein from an Advanced Vaccine Candidate. Science 2020, 370, 1089–1094.

- Block, S.L.; Nolan, T.; Sattler, C.; Barr, E.; Giacoletti, K.E.D.; Marchant, C.D.; Castellsagué, X.; Rusche, S.A.; Lukac, S.; Bryan, J.T.; et al. Comparison of the Immunogenicity and Reactogenicity of a Prophylactic Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus (Types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 Virus-Like Particle Vaccine in Male and Female Adolescents and Young Adult Women. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 2135–2145.

- Cohen, A.A.; Gnanapragasam, P.N.P.; Lee, Y.E.; Hoffman, P.R.; Ou, S.; Kakutani, L.M.; Keeffe, J.R.; Wu, H.-J.; Howarth, M.; West, A.P.; et al. Mosaic Nanoparticles Elicit Cross-Reactive Immune Responses to Zoonotic Coronaviruses in Mice. Science 2021, 371, 735–741.

- Keech, C.; Albert, G.; Cho, I.; Robertson, A.; Reed, P.; Neal, S.; Plested, J.S.; Zhu, M.; Cloney-Clark, S.; Zhou, H.; et al. Phase 1–2 Trial of a SARS-CoV-2 Recombinant Spike Protein Nanoparticle Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2320–2332.

- Tian, J.H.; Patel, N.; Haupt, R.; Zhou, H.; Weston, S.; Hammond, H.; Logue, J.; Portnoff, A.D.; Norton, J.; Guebre-Xabier, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Vaccine Candidate NVX-CoV2373 Immunogenicity in Baboons and Protection in Mice. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 372.

- Ward, B.J.; Makarkov, A.; Séguin, A.; Pillet, S.; Trépanier, S.; Dhaliwall, J.; Libman, M.D.; Vesikari, T.; Landry, N. Efficacy, Immunogenicity, and Safety of a Plant-Derived, Quadrivalent, Virus-like Particle Influenza Vaccine in Adults (18–64 Years) and Older Adults (≥65 Years): Two Multicentre, Randomised Phase 3 Trials. Lancet 2020, 396, 1491–1503.

- Braun, M.; Jandus, C.; Maurer, P.; Hammann-Haenni, A.; Schwarz, K.; Bachmann, M.F.; Speiser, D.E.; Romero, P. Virus-like Particles Induce Robust Human T-Helper Cell Responses: Cellular Immune Response. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 330–340.

- Nooraei, S.; Bahrulolum, H.; Hoseini, Z.S.; Katalani, C.; Hajizade, A.; Easton, A.J.; Ahmadian, G. Virus-like Particles: Preparation, Immunogenicity and Their Roles as Nanovaccines and Drug Nanocarriers. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 59.

- Li, M.; Cripe, T.P.; Estes, P.A.; Lyon, M.K.; Rose, R.C.; Garcea, R.L. Expression of the Human Papillomavirus Type 11 L1 Capsid Protein in Escherichia Coli: Characterization of Protein Domains Involved in DNA Binding and Capsid Assembly. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 2988–2995.

- Yang, Y.; Shi, W.; Abiona, O.M.; Nazzari, A.; Olia, A.S.; Ou, L.; Phung, E.; Stephens, T.; Tsybovsky, Y.; Verardi, R.; et al. Newcastle Disease Virus-Like Particles Displaying Prefusion-Stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spikes Elicit Potent Neutralizing Responses. Vaccines 2021, 9, 73.

- Brouwer, P.J.M.; Caniels, T.G.; van der Straten, K.; Snitselaar, J.L.; Aldon, Y.; Bangaru, S.; Torres, J.L.; Okba, N.M.A.; Claireaux, M.; Kerster, G.; et al. Potent Neutralizing Antibodies from COVID-19 Patients Define Multiple Targets of Vulnerability. Science 2020, 369, 643–650.

- Dormitzer, P.R.; Ulmer, J.B.; Rappuoli, R. Structure-Based Antigen Design: A Strategy for next Generation Vaccines. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 659–667.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Xia, H.; Zhang, X.; Fontes-Garfias, C.R.; Swanson, K.A.; Cai, H.; Sarkar, R.; Chen, W.; Cutler, M.; et al. Neutralizing Activity of BNT162b2-Elicited Serum. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1466–1468.

- Pallesen, J.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Wrapp, D.; Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Turner, H.L.; Cottrell, C.A.; Becker, M.M.; Wang, L.; Shi, W.; et al. Immunogenicity and Structures of a Rationally Designed Prefusion MERS-CoV Spike Antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E7348–E7357.

- Wec, A.Z.; Wrapp, D.; Herbert, A.S.; Maurer, D.P.; Haslwanter, D.; Sakharkar, M.; Jangra, R.K.; Dieterle, M.E.; Lilov, A.; Huang, D.; et al. Broad Neutralization of SARS-Related Viruses by Human Monoclonal Antibodies. Science 2020, 369, 731–736.

- Gardner, A.; Autin, L.; Barbaro, B.; Olson, A.J.; Goodsell, D.S. CellPAINT: Interactive Illustration of Dynamic Mesoscale Cellular Environments. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2018, 38, 51–64.Yao, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, N.; Xu, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; Weng, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.; et al. Molecular Architecture of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus. Cell 2020, 183, 730–738.e13.

- Tomasello, G.; Armenia, I.; Molla, G. The Protein Imager: A Full-Featured Online Molecular Viewer Interface with Server-Side HQ-Rendering Capabilities. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2909–2911.Caldas, L.A.; Carneiro, F.A.; Higa, L.M.; Monteiro, F.L.; da Silva, G.P.; da Costa, L.J.; Durigon, E.L.; Tanuri, A.; de Souza, W. Ultrastructural Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Interactions with the Host Cell via High Resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16099.

- Yao, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, N.; Xu, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; Weng, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.; et al. Molecular Architecture of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus. Cell 2020, 183, 730–738.e13. Zhao, P.; Praissman, J.L.; Grant, O.C.; Cai, Y.; Xiao, T.; Rosenbalm, K.E.; Aoki, K.; Kellman, B.P.; Bridger, R.; Barouch, D.H.; et al. Virus-Receptor Interactions of Glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 Spike and Human ACE2 Receptor. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 586–601.e6.

- Caldas, L.A.; Carneiro, F.A.; Higa, L.M.; Monteiro, F.L.; da Silva, G.P.; da Costa, L.J.; Durigon, E.L.; Tanuri, A.; de Souza, W. Ultrastructural Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Interactions with the Host Cell via High Resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16099. Muus, C.; Luecken, M.D.; Eraslan, G.; Sikkema, L.; Waghray, A.; Heimberg, G.; Kobayashi, Y.; Vaishnav, E.D.; Subramanian, A.; Smillie, C.; et al. Single-Cell Meta-Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Entry Genes across Tissues and Demographics. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 546–559.

- Zhao, P.; Praissman, J.L.; Grant, O.C.; Cai, Y.; Xiao, T.; Rosenbalm, K.E.; Aoki, K.; Kellman, B.P.; Bridger, R.; Barouch, D.H.; et al. Virus-Receptor Interactions of Glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 Spike and Human ACE2 Receptor. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 586–601.e6. Sungnak, W.; Huang, N.; Bécavin, C.; Berg, M.; Queen, R.; Litvinukova, M.; Talavera-López, C.; Maatz, H.; Reichart, D.; Sampaziotis, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Entry Factors Are Highly Expressed in Nasal Epithelial Cells Together with Innate Immune Genes. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 681–687.

- Muus, C.; Luecken, M.D.; Eraslan, G.; Sikkema, L.; Waghray, A.; Heimberg, G.; Kobayashi, Y.; Vaishnav, E.D.; Subramanian, A.; Smillie, C.; et al. Single-Cell Meta-Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Entry Genes across Tissues and Demographics. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 546–559. Li, W.; Wicht, O.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; He, Q.; Rottier, P.J.M.; Bosch, B.-J. A Single Point Mutation Creating a Furin Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein Renders Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Coronavirus Trypsin Independent for Cell Entry and Fusion. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 8077–8081.

- Sungnak, W.; Huang, N.; Bécavin, C.; Berg, M.; Queen, R.; Litvinukova, M.; Talavera-López, C.; Maatz, H.; Reichart, D.; Sampaziotis, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Entry Factors Are Highly Expressed in Nasal Epithelial Cells Together with Innate Immune Genes. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 681–687. Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q. Structural Basis for the Recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by Full-Length Human ACE2. Science 2020, 367, 1444–1448.

- Li, W.; Wicht, O.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; He, Q.; Rottier, P.J.M.; Bosch, B.-J. A Single Point Mutation Creating a Furin Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein Renders Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Coronavirus Trypsin Independent for Cell Entry and Fusion. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 8077–8081. Mercurio, I.; Tragni, V.; Busto, F.; De Grassi, A.; Pierri, C.L. Protein Structure Analysis of the Interactions between SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and the Human ACE2 Receptor: From Conformational Changes to Novel Neutralizing Antibodies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 1501–1522.

- Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q. Structural Basis for the Recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by Full-Length Human ACE2. Science 2020, 367, 1444–1448. Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Pöhlmann, S. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 779–784.e5.

- Mercurio, I.; Tragni, V.; Busto, F.; De Grassi, A.; Pierri, C.L. Protein Structure Analysis of the Interactions between SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and the Human ACE2 Receptor: From Conformational Changes to Novel Neutralizing Antibodies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 1501–1522. Plotkin, S.; Robinson, J.M.; Cunningham, G.; Iqbal, R.; Larsen, S. The Complexity and Cost of Vaccine Manufacturing—An Overview. Vaccine 2017, 35, 4064–4071.

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Pöhlmann, S. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 779–784.e5. Shang, J.; Ye, G.; Shi, K.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Aihara, H.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Structural Basis of Receptor Recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 581, 221–224.

- Plotkin, S.; Robinson, J.M.; Cunningham, G.; Iqbal, R.; Larsen, S. The Complexity and Cost of Vaccine Manufacturing—An Overview. Vaccine 2017, 35, 4064–4071. Gallagher, T.M. Murine Coronavirus Membrane Fusion Is Blocked by Modification of Thiols Buried within the Spike Protein. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 4683–4690.

- Shang, J.; Ye, G.; Shi, K.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Aihara, H.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Structural Basis of Receptor Recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 581, 221–224. Lavillette, D.; Barbouche, R.; Yao, Y.; Boson, B.; Cosset, F.-L.; Jones, I.M.; Fenouillet, E. Significant Redox Insensitivity of the Functions of the SARS-CoV Spike Glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9200–9204.

- Gallagher, T.M. Murine Coronavirus Membrane Fusion Is Blocked by Modification of Thiols Buried within the Spike Protein. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 4683–4690. Costello, D.A.; Millet, J.K.; Hsia, C.-Y.; Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S. Single Particle Assay of Coronavirus Membrane Fusion with Proteinaceous Receptor-Embedded Supported Bilayers. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 7895–7904.

- Lavillette, D.; Barbouche, R.; Yao, Y.; Boson, B.; Cosset, F.-L.; Jones, I.M.; Fenouillet, E. Significant Redox Insensitivity of the Functions of the SARS-CoV Spike Glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9200–9204. Giron, C.C.; Laaksonen, A.; Barroso da Silva, F.L. Up State of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Homotrimer Favors an Increased Virulence for New Variants. Front. Med. Technol. 2021, 3.

- Costello, D.A.; Millet, J.K.; Hsia, C.-Y.; Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S. Single Particle Assay of Coronavirus Membrane Fusion with Proteinaceous Receptor-Embedded Supported Bilayers. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 7895–7904. Letko, M.; Marzi, A.; Munster, V. Functional Assessment of Cell Entry and Receptor Usage for SARS-CoV-2 and Other Lineage B Betacoronaviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 562–569.

- Giron, C.C.; Laaksonen, A.; Barroso da Silva, F.L. Up State of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Homotrimer Favors an Increased Virulence for New Variants. Front. Med. Technol. 2021, 3. Zhang, C.; Zheng, W.; Huang, X.; Bell, E.W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Protein Structure and Sequence Reanalysis of 2019-NCoV Genome Refutes Snakes as Its Intermediate Host and the Unique Similarity between Its Spike Protein Insertions and HIV-1. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 1351–1360.

- Letko, M.; Marzi, A.; Munster, V. Functional Assessment of Cell Entry and Receptor Usage for SARS-CoV-2 and Other Lineage B Betacoronaviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 562–569. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, W.; Huang, X.; Bell, E.W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Protein Structure and Sequence Reanalysis of 2019-NCoV Genome Refutes Snakes as Its Intermediate Host and the Unique Similarity between Its Spike Protein Insertions and HIV-1. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 1351–1360. Davies, N.G.; Abbott, S.; Barnard, R.C.; Jarvis, C.I.; Kucharski, A.J.; Munday, J.D.; Pearson, C.A.B.; Russell, T.W.; Tully, D.C.; Washburne, A.D.; et al. Estimated Transmissibility and Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Science 2020, 372.

- Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ (accessed on 5 July 2021).Tegally, H.; Wilkinson, E.; Giovanetti, M.; Iranzadeh, A.; Fonseca, V.; Giandhari, J.; Doolabh, D.; Pillay, S.; San, E.J.; Msomi, N.; et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern in South Africa. Nature 2021, 592, 438–443.

- Davies, N.G.; Abbott, S.; Barnard, R.C.; Jarvis, C.I.; Kucharski, A.J.; Munday, J.D.; Pearson, C.A.B.; Russell, T.W.; Tully, D.C.; Washburne, A.D.; et al. Estimated Transmissibility and Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Science 2020, 372. Faria, N.R.; Mellan, T.A.; Whittaker, C.; Claro, I.M.; Candido, D.d.S.; Mishra, S.; Crispim, M.A.E.; Sales, F.C.S.; Hawryluk, I.; McCrone, J.T.; et al. Genomics and Epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 Lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science 2021, 372, 815–821.

- Schrödinger The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Available online: https://pymol.org/2/ (accessed on 5 July 2021).Cherian, S.; Potdar, V.; Jadhav, S.; Yadav, P.; Gupta, N.; Das, M.; Rakshit, P.; Singh, S.; Abraham, P.; Panda, S.; et al. Convergent Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutations, L452R, E484Q, and P681R, in the Second Wave of COVID-19 in Maharashtra, India. BioRxiv 2021.

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, W.; Huang, X.; Bell, E.W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Protein Structure and Sequence Reanalysis of 2019-NCoV Genome Refutes Snakes as Its Intermediate Host and the Unique Similarity between Its Spike Protein Insertions and HIV-1. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 1351–1360.Plescia, C.B.; David, E.A.; Patra, D.; Sengupta, R.; Amiar, S.; Su, Y.; Stahelin, R. V SARS-CoV-2 Viral Budding and Entry Can Be Modeled Using BSL-2 Level Virus-like Particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100103.

- Zhang Modeling of the SARS-CoV-2 Genome Using I-TASSER. Available online: https://zhanggroup.org/COVID-19/ (accessed on 24 August 2021).Xu, R.; Shi, M.; Li, J.; Song, P.; Li, N. Corrigendum: Construction of SARS-CoV-2 Virus-Like Particles by Mammalian Expression System. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 1026.

- Tegally, H.; Wilkinson, E.; Giovanetti, M.; Iranzadeh, A.; Fonseca, V.; Giandhari, J.; Doolabh, D.; Pillay, S.; San, E.J.; Msomi, N.; et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern in South Africa. Nature 2021, 592, 438–443. Fluckiger, A.-C.; Ontsouka, B.; Bozic, J.; Diress, A.; Ahmed, T.; Berthoud, T.; Tran, A.; Duque, D.; Liao, M.; Mccluskie, L.; et al. An Enveloped Virus-like Particle Vaccine Expressing a Stabilized Prefusion Form of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Elicits Potent Immunity after a Single Dose. bioRxiv 2021.

- Faria, N.R.; Mellan, T.A.; Whittaker, C.; Claro, I.M.; Candido, D.d.S.; Mishra, S.; Crispim, M.A.E.; Sales, F.C.S.; Hawryluk, I.; McCrone, J.T.; et al. Genomics and Epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 Lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science 2021, 372, 815–821. Ward, B.J.; Gobeil, P.; Séguin, A.; Atkins, J.; Boulay, I.; Charbonneau, P.-Y.; Couture, M.; D’Aoust, M.-A.; Dhaliwall, J.; Finkle, C.; et al. Phase 1 Randomized Trial of a Plant-Derived Virus-like Particle Vaccine for COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1071–1078.

- Cherian, S.; Potdar, V.; Jadhav, S.; Yadav, P.; Gupta, N.; Das, M.; Rakshit, P.; Singh, S.; Abraham, P.; Panda, S.; et al. Convergent Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutations, L452R, E484Q, and P681R, in the Second Wave of COVID-19 in Maharashtra, India. BioRxiv 2021. Garçon, N.; Vaughn, D.W.; Didierlaurent, A.M. Development and Evaluation of AS03, an Adjuvant System Containing α-Tocopherol and Squalene in an Oil-in-Water Emulsion. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2012, 11, 349–366.

- Plescia, C.B.; David, E.A.; Patra, D.; Sengupta, R.; Amiar, S.; Su, Y.; Stahelin, R. V SARS-CoV-2 Viral Budding and Entry Can Be Modeled Using BSL-2 Level Virus-like Particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100103. Keating, G.M.; Noble, S. Recombinant Hepatitis B Vaccine (Engerix-B??): A Review of Its Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy Against Hepatitis B. Drugs 2003, 63, 1021–1051.

- Xu, R.; Shi, M.; Li, J.; Song, P.; Li, N. Corrigendum: Construction of SARS-CoV-2 Virus-Like Particles by Mammalian Expression System. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 1026. Kumar, S.; Maurya, V.K.; Prasad, A.K.; Bhatt, M.L.B.; Saxena, S.K. Structural, Glycosylation and Antigenic Variation between 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV) and SARS Coronavirus (SARS-CoV). Virusdisease 2020, 31, 13–21.

- Fluckiger, A.-C.; Ontsouka, B.; Bozic, J.; Diress, A.; Ahmed, T.; Berthoud, T.; Tran, A.; Duque, D.; Liao, M.; Mccluskie, L.; et al. An Enveloped Virus-like Particle Vaccine Expressing a Stabilized Prefusion Form of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Elicits Potent Immunity after a Single Dose. bioRxiv 2021. Rudd, P.M.; Wormald, M.R.; Stanfield, R.L.; Huang, M.; Mattsson, N.; Speir, J.A.; DiGennaro, J.A.; Fetrow, J.S.; Dwek, R.A.; Wilson, I.A. Roles for Glycosylation of Cell Surface Receptors Involved in Cellular Immune Recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 293, 351–366.

- Ward, B.J.; Gobeil, P.; Séguin, A.; Atkins, J.; Boulay, I.; Charbonneau, P.-Y.; Couture, M.; D’Aoust, M.-A.; Dhaliwall, J.; Finkle, C.; et al. Phase 1 Randomized Trial of a Plant-Derived Virus-like Particle Vaccine for COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1071–1078. Monie, A.; Hung, C.-F.; Roden, R.; Wu, T.-C. Cervarix: A Vaccine for the Prevention of HPV 16, 18-Associated Cervical Cancer. Biologics 2008, 2, 97–105.

- Garçon, N.; Vaughn, D.W.; Didierlaurent, A.M. Development and Evaluation of AS03, an Adjuvant System Containing α-Tocopherol and Squalene in an Oil-in-Water Emulsion. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2012, 11, 349–366. Giannini, S.L.; Hanon, E.; Moris, P.; Van Mechelen, M.; Morel, S.; Dessy, F.; Fourneau, M.A.; Colau, B.; Suzich, J.; Losonksy, G.; et al. Enhanced Humoral and Memory B Cellular Immunity Using HPV16/18 L1 VLP Vaccine Formulated with the MPL/Aluminium Salt Combination (AS04) Compared to Aluminium Salt Only. Vaccine 2006, 24, 5937–5949.

- Keating, G.M.; Noble, S. Recombinant Hepatitis B Vaccine (Engerix-B??): A Review of Its Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy Against Hepatitis B. Drugs 2003, 63, 1021–1051. Paavonen, J.; Jenkins, D.; Bosch, F.X.; Naud, P.; Salmerón, J.; Wheeler, C.M.; Chow, S.-N.; Apter, D.L.; Kitchener, H.C.; Castellsague, X.; et al. Efficacy of a Prophylactic Adjuvanted Bivalent L1 Virus-like-Particle Vaccine against Infection with Human Papillomavirus Types 16 and 18 in Young Women: An Interim Analysis of a Phase III Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2007, 369, 2161–2170.

- Kumar, S.; Maurya, V.K.; Prasad, A.K.; Bhatt, M.L.B.; Saxena, S.K. Structural, Glycosylation and Antigenic Variation between 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV) and SARS Coronavirus (SARS-CoV). Virusdisease 2020, 31, 13–21. Harper, D.M.; Franco, E.L.; Wheeler, C.M.; Moscicki, A.-B.; Romanowski, B.; Roteli-Martins, C.M.; Jenkins, D.; Schuind, A.; Costa Clemens, S.A.; Dubin, G. Sustained Efficacy up to 4·5 Years of a Bivalent L1 Virus-like Particle Vaccine against Human Papillomavirus Types 16 and 18: Follow-up from a Randomised Control Trial. Lancet 2006, 367, 1247–1255.

- Rudd, P.M.; Wormald, M.R.; Stanfield, R.L.; Huang, M.; Mattsson, N.; Speir, J.A.; DiGennaro, J.A.; Fetrow, J.S.; Dwek, R.A.; Wilson, I.A. Roles for Glycosylation of Cell Surface Receptors Involved in Cellular Immune Recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 293, 351–366. de Villiers, E.M. Heterogeneity of the Human Papillomavirus Group. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 4898–4903.

- Monie, A.; Hung, C.-F.; Roden, R.; Wu, T.-C. Cervarix: A Vaccine for the Prevention of HPV 16, 18-Associated Cervical Cancer. Biologics 2008, 2, 97–105. Walls, A.C.; Fiala, B.; Schäfer, A.; Wrenn, S.; Pham, M.N.; Murphy, M.; Tse, L.V.; Shehata, L.; O’Connor, M.A.; Chen, C.; et al. Elicitation of Potent Neutralizing Antibody Responses by Designed Protein Nanoparticle Vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. Cell 2020, 183, 1367–1382.e17.

- Giannini, S.L.; Hanon, E.; Moris, P.; Van Mechelen, M.; Morel, S.; Dessy, F.; Fourneau, M.A.; Colau, B.; Suzich, J.; Losonksy, G.; et al. Enhanced Humoral and Memory B Cellular Immunity Using HPV16/18 L1 VLP Vaccine Formulated with the MPL/Aluminium Salt Combination (AS04) Compared to Aluminium Salt Only. Vaccine 2006, 24, 5937–5949. Arunachalam, P.S.; Walls, A.C.; Golden, N.; Atyeo, C.; Fischinger, S.; Li, C.; Aye, P.; Navarro, M.J.; Lai, L.; Edara, V.V.; et al. Adjuvanting a Subunit COVID-19 Vaccine to Induce Protective Immunity. Nature 2021, 594, 253–258.

- Paavonen, J.; Jenkins, D.; Bosch, F.X.; Naud, P.; Salmerón, J.; Wheeler, C.M.; Chow, S.-N.; Apter, D.L.; Kitchener, H.C.; Castellsague, X.; et al. Efficacy of a Prophylactic Adjuvanted Bivalent L1 Virus-like-Particle Vaccine against Infection with Human Papillomavirus Types 16 and 18 in Young Women: An Interim Analysis of a Phase III Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2007, 369, 2161–2170. Heath, P.T.; Galiza, E.P.; Baxter, D.N.; Boffito, M.; Browne, D.; Burns, F.; Chadwick, D.R.; Clark, R.; Cosgrove, C.; Galloway, J.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1172–1183.

- Harper, D.M.; Franco, E.L.; Wheeler, C.M.; Moscicki, A.-B.; Romanowski, B.; Roteli-Martins, C.M.; Jenkins, D.; Schuind, A.; Costa Clemens, S.A.; Dubin, G. Sustained Efficacy up to 4·5 Years of a Bivalent L1 Virus-like Particle Vaccine against Human Papillomavirus Types 16 and 18: Follow-up from a Randomised Control Trial. Lancet 2006, 367, 1247–1255. Fougeroux, C.; Goksøyr, L.; Idorn, M.; Soroka, V.; Myeni, S.K.; Dagil, R.; Janitzek, C.M.; Søgaard, M.; Aves, K.-L.; Horsted, E.W.; et al. Capsid-like Particles Decorated with the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor-Binding Domain Elicit Strong Virus Neutralization Activity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 324.

- de Villiers, E.M. Heterogeneity of the Human Papillomavirus Group. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 4898–4903. Zhou, H.; Ji, J.; Chen, X.; Bi, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Hu, T.; Song, H.; Zhao, R.; Chen, Y.; et al. Identification of Novel Bat Coronaviruses Sheds Light on the Evolutionary Origins of SARS-CoV-2 and Related Viruses. Cell 2021, 184, 4380–4391.e14.

- Walls, A.C.; Fiala, B.; Schäfer, A.; Wrenn, S.; Pham, M.N.; Murphy, M.; Tse, L.V.; Shehata, L.; O’Connor, M.A.; Chen, C.; et al. Elicitation of Potent Neutralizing Antibody Responses by Designed Protein Nanoparticle Vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. Cell 2020, 183, 1367–1382.e17. Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.-L. Origin and Evolution of Pathogenic Coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192.

- Arunachalam, P.S.; Walls, A.C.; Golden, N.; Atyeo, C.; Fischinger, S.; Li, C.; Aye, P.; Navarro, M.J.; Lai, L.; Edara, V.V.; et al. Adjuvanting a Subunit COVID-19 Vaccine to Induce Protective Immunity. Nature 2021, 594, 253–258. Rappazzo, C.G.; Tse, L.V.; Kaku, C.I.; Wrapp, D.; Sakharkar, M.; Huang, D.; Deveau, L.M.; Yockachonis, T.J.; Herbert, A.S.; Battles, M.B.; et al. Broad and Potent Activity against SARS-like Viruses by an Engineered Human Monoclonal Antibody. Science 2021, 371, 823–829.

- Heath, P.T.; Galiza, E.P.; Baxter, D.N.; Boffito, M.; Browne, D.; Burns, F.; Chadwick, D.R.; Clark, R.; Cosgrove, C.; Galloway, J.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1172–1183. Powell, A.E.; Zhang, K.; Sanyal, M.; Tang, S.; Weidenbacher, P.A.; Li, S.; Pham, T.D.; Pak, J.E.; Chiu, W.; Kim, P.S. A Single Immunization with Spike-Functionalized Ferritin Vaccines Elicits Neutralizing Antibody Responses against SARS-CoV-2 in Mice. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 183–199.

- Fougeroux, C.; Goksøyr, L.; Idorn, M.; Soroka, V.; Myeni, S.K.; Dagil, R.; Janitzek, C.M.; Søgaard, M.; Aves, K.-L.; Horsted, E.W.; et al. Capsid-like Particles Decorated with the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor-Binding Domain Elicit Strong Virus Neutralization Activity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 324. Liu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Wang, W.; Tan, W.; Fu, Y.-X.; Zhu, M. A Novel Method for Synthetic Vaccine Construction Based on Protein Assembly. Sci. Rep. 2015, 4, 7266.

- Zhou, H.; Ji, J.; Chen, X.; Bi, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Hu, T.; Song, H.; Zhao, R.; Chen, Y.; et al. Identification of Novel Bat Coronaviruses Sheds Light on the Evolutionary Origins of SARS-CoV-2 and Related Viruses. Cell 2021, 184, 4380–4391.e14. Bale, J.B.; Gonen, S.; Liu, Y.; Sheffler, W.; Ellis, D.; Thomas, C.; Cascio, D.; Yeates, T.O.; Gonen, T.; King, N.P.; et al. Accurate Design of Megadalton-Scale Two-Component Icosahedral Protein Complexes. Science 2016, 353, 389–394.

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.-L. Origin and Evolution of Pathogenic Coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192.

- Rappazzo, C.G.; Tse, L.V.; Kaku, C.I.; Wrapp, D.; Sakharkar, M.; Huang, D.; Deveau, L.M.; Yockachonis, T.J.; Herbert, A.S.; Battles, M.B.; et al. Broad and Potent Activity against SARS-like Viruses by an Engineered Human Monoclonal Antibody. Science 2021, 371, 823–829.

- Powell, A.E.; Zhang, K.; Sanyal, M.; Tang, S.; Weidenbacher, P.A.; Li, S.; Pham, T.D.; Pak, J.E.; Chiu, W.; Kim, P.S. A Single Immunization with Spike-Functionalized Ferritin Vaccines Elicits Neutralizing Antibody Responses against SARS-CoV-2 in Mice. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 183–199.

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Wang, W.; Tan, W.; Fu, Y.-X.; Zhu, M. A Novel Method for Synthetic Vaccine Construction Based on Protein Assembly. Sci. Rep. 2015, 4, 7266.

- Bale, J.B.; Gonen, S.; Liu, Y.; Sheffler, W.; Ellis, D.; Thomas, C.; Cascio, D.; Yeates, T.O.; Gonen, T.; King, N.P.; et al. Accurate Design of Megadalton-Scale Two-Component Icosahedral Protein Complexes. Science 2016, 353, 389–394.