Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 4 by Jessie Wu and Version 3 by Jessie Wu.

Headache is the first cause of consultation in neurology, and one of the most frequent reasons for consultation in general medicine. Migraine is one of the most common, prevalent, and socioeconomically impactful disabling primary headache disorders. Neuroticism can be conceptualized as a disposition to suffer anxiety and emotional disorders in general. Neuroticism has been associated with various mental and physical disorders (e.g., chronic pain, depression), including migraine.

- migraine

- neuroticism

- chronic pain

1. Introduction

Headache is the first cause of consultation in neurology, and one of the most frequent reasons for consultation in a general medicine office [1]. They are classified as primary when there is no organic or other known reason, and secondary when there is an organic sign. Among the primary headaches are migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache (acuminate, histamine, or Horton), and others not classified within the aforementioned types [2][3]. Although tension-type headache seems to be the most frequent in daily practice, it is no less true that migraine is precisely the most disabling from the social, economic, and psychological points of view [1][2][3][4].

In effect, migraine is one of the most common disabling primary headache disorders and several epidemiological studies have confirmed its high prevalence and negative socio-economic and personal impact (i.e., problems at work, in relationships, in academic field, in social spheres, etc.) [5]. In the 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD), migraine was ranked as the third most prevalent disorder in the world. Some years later, in the 2015 GBD, it was the third highest cause of disability worldwide in both males and females under the age of 50 years [5]. The evident burden of headaches provoked a call to action by the Word Health Organization (WHO) in different years (i.e., 2004, 2011). On purpose, WHO, in association with the non-governmental organization Lifting the Burden, participates in the Global Headache Campaign. This initiative, launched in 2004 and still active today, aims to raise awareness of the problem and also improve the quality of care and access to it provided to people with headaches worldwide [6].

In addition, personality remains as a central aspect in psychology and therapy. One possible explanation factor is the need to consider the personality traits (i.e., habitual patterns of behavior, thought, and emotion such as neuroticism, psychoticism, extraversion, coping strategies, etc.) in the treatment of each disease [7][8]. By including personality traits in treatment and management of illnesses, it would make possible a more personalized approach for these patients and it seems to be related to a reduction of medication overuse [8]. In this sense, neuroticism is one of the most studied personality traits due to is implications for the health, not only mental but also physical [8][9]. Neuroticism can be considered as a disposition to suffer anxiety and emotional disorders in general [10]. Moreover, neuroticism has been associated with various mental disorders (especially anxiety and depression), the morbidity and mortality of various physical diseases (including migraine, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, temporomandibular disorder), a greater number of medical complications, increasing frequency of health services use, and worse prognosis and health-related quality of life [9][11][12][13][14]. Moreover, it is important to notice that migraine patients usually show higher level of neuroticism and vulnerability to experience negative affect, compared to non-migraineurs patients [15][16][17][18][19][20][21].

2. Insights into Neuroticism

Neuroticism is a dimension related to the disposition to suffer what classically is known as neurotic disorders, including both anxiety and emotional disorders in general. An individual with high neuroticism tend to be anxious, depressed, tense, irrational, shy, sad, emotional unstable, and distinguished by low self-esteem and frequent feelings of guilt as well [10]. In general, neuroticism is characterized by emotional instability, fear, nervous disposition, insecurity, temperamental behavior, impatience, self-consciousness, and impulsive behavior [22][23].

The possible neurobiological bases of neuroticism include the visceral brain (or limbic system), composed by structures such as the medial septum, hippocampus, amygdala, cingulum, and hypothalamus [10][24]. The limbic system comprises a group of structures, including those in the limbic lobe and Papez circuit, which are anatomically interconnected and are probably involved in emotion, learning, and memory [25][26].

There is no doubt about the importance of continuing to invasitigate the health implications of neuroticism. Neuroticism has been identified as a strong correlate and predictor of various mental disorders (especially depression and anxiety) and the morbidity and mortality of various physical diseases (i.e., diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, dermatological, respiratory and gastrointestinal problems, fibromyalgia, temporomandibular disorder, chronic pain in general, and even cancer) [9][11][13][27]. Furthermore, the comorbidity among the above reported diseases and neuroticism has been suggested to lead to a greater number of complications, an increase in the frequency of use of health services, worse prognosis, and lesser health-related quality of life [11][12]. Neuroticism has also been considered a risk factor for developing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) [28][29][30][31] and chronic pain in general (i.e., fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, etc.) 8 [11][14][27].

Moreover, personality seems to determine the coping strategies that people will use in stressful situations, being those, in turn, that will allow the subject a high or low level of adaptation. The studies that are framed, assuming these statements, evaluate the possible relationship between the levels of a certain dispositional personality variables and the use of certain coping strategies. Specifically, these studies try to determine whether certain variables of personality lead to use coping strategies that at the same time lead to a low level of adaptation to the disease [14]. In this sense, most of the research has focused on neuroticism, and the results show the existence of a significant relationship between high levels of neuroticism and coping strategies that predict poor adaptation to the disease [8][9][13][27]. Thus, empirical evidence has been found that supports an increase in the probability of using ineffective coping strategies for stress management by subjects with high scores in neuroticism, such as, for instance, catastrophizing. High levels of neuroticism might be also be related to pain catastrophizing and a more passive-oriented stress and pain coping strategies [9][32][33][34]. At the same time, passive coping strategies predict higher perceived pain intensity [14][35]. In addition, the relation between neuroticism and chronic pain is mediated by the propensity of high-neuroticism individuals to catastrophize their pain [14]. At this regard, catastrophizing appears to reduce the health-related quality of life and worsen symptoms in several chronic pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia [7][36][37] and migraine [38][39][40]. Therefore, exploring neuroticism is useful in order to better understand the pain coping strategies and improve them and the treatment of these patients.

In the same line, it has been reported that the use of maladaptive coping strategies and some personality characteristics such as neuroticism and the presence of personality maladjustments can be considered vulnerability factors for a worse evolution in general and specifically in adaptation disorders. In fact, it seems that the use of these types of coping strategies modulates the relationship between neuroticism and psychological distress [34]. Therefore, they should be considered both in the evaluation and in the development of preventive or intervention strategies, which should be prioritized in people with psychological disorders (i.e., adaptation disorder) that present these characteristics [41].

3. Migraine and Neuroticism

Related to the main objective of this current review, which refers to exploring in depth the relationship between migraine and neuroticism, many affected headache patients show a tendency to experience more negative emotions and stress. This is in line with previous studies, which compare chronic headache patients to healthy controls [42]. Several researchers have studied the relation between migraine and neuroticism based on the Five Factor Model personality approach, which is a hierarchical system of personality in terms of five basic independent domains: neuroticism, extroversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. In this frame, neuroticism is conceptualized as the tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anxiety, fear, and frustration [43]. Additionally, some researchers—based on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)—have found the “neurotic triad,” which includes hypochondria, hysteria, and depression, in tension-type headache and migraine patients [44]. Furthermore, it has been confirmed that migraine patients have significantly higher levels of neuroticism scores than non-migraine controls, using the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ), which assesses neuroticism, extraversion, and psychoticism, together with a Lie/Social Desirability scale [45][46][47].

According to the research evidence, migraine patients usually have a higher level of neuroticism and vulnerability to negative affect, in comparison with non-migraineurs patients [15][16][17][18][19][20][21]. These findings and personality characteristics described are usually associated and are more evident in the cases of greater intensity, duration in time, and frequency of migraine attacks [48]. For that reason, some studies suggest that this type of personality trait is more related to chronic pain than to migraine itself [48][49]; hence, the importance of treating migraines early and properly. Nevertheless, it is a theme still under research and no clear data have been provided at all. What it is evident is that migraineurs studies showed a strong correlation between neuroticism and headache duration [50], though, indeed, when it includes males, no association with duration is found [15]. In the same way, a research comparing migraineurs to their siblings without migraine reported that neuroticism was not associated with attack frequency or severity [51]. Moreover, migraine in childhood diagnosed by physicians and higher trait neuroticism have been significantly related to the prevalence of migraine in adulthood [52]. In fact, neuroticism seems to increase the risk of migraine [53].

A high neuroticism score predisposes to depression and anxiety [16][54], which is clinically interesting, because medication-overuse headache migraine (MOH) patients are diagnosed with depression more frequently than migraineurs [16][55][56].

Previous studies have stated a strong association between high score on the personality domain neuroticism and depression [54]. Although, both migraine and MOH patients have increased risk of developing depression, medication-overuse headache migraine patients have a higher prevalence of depression compared to migraine patients in general [55]. The personality domain neuroticism (risk factor) and extraversion (protective factor) have been linked to general health [57]. A high score on neuroticism has been linked to poor prognosis and health-related quality of life in migraine patients [15][58][59]. The previous research revealed that neuroticism moderated the relationship between depression and migraine [20].

Neuroticism has been also studied in migraine patients compared to tension-type headache (TTH) patients [60]. In this sense, neuroticism and depression scores have been associated with headache frequency (chronic vs. episodic), being higher for migraine and TTH followed by pure TTH [60].

The relation between depression and neuroticism in migraine is an important element. Some authors consider that both neuroticism and depression may influence pain sensitivity and pain perception thresholds in humans [61][62][63][64]. In addition, it is well-known that personality traits’ may affect the individual’s vulnerability and the use of non-adaptive coping strategies facing various types of disease, including pain conditions [37]. In the same line, neuroticism seems to alter pain perception; lower pain thresholds have been found in persons with high levels of neuroticism in comparison with persons with lower levels of neuroticism [65]. Moreover, neuroticism has been related to greater vigilance to pain, pain catastrophizing, and fear of movement/re-injury in patients with non-specific chronic or recurrent pain [62]. Cutaneous allodynia, which may indicate central sensitization, has been shown to be associated with depression in migraineurs [66]. Moreover, depression has been revealed to be associated with an increased risk of transformation from episodic to chronic migraine [67], where neuroticism might be a mediator factor.

In general, migraine patients with comorbid depression and anxiety had more neuroticism than patients without migraines and those with depression or anxiety without migraines [68][69]. As neuroticism is significantly related to symptoms of anxiety and depression [70][71], treatment for migraine might be more effective if it included interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [72]—which is considered one of the most effective interventions for depression—together with the usual medical treatment [73]. Nevertheless, it is important to be cautious in assuming that depression and neuroticism are related to migraine through the same mechanism. Given that neuroticism is a relatively stable aspect of an individual’s personality, it seems likely that genetically predisposed people will show a certain level of neuroticism throughout their lives, and throughout their lives, at some point, may develop migraine, possibly under the influence of different factors (i.e., hormonal changes and environmental stressors) [53]. By contrast, anxiety and depressive disorders are usually episodic and the mechanism that causes their association with migraine may be different [53].

In fact, it is well-known that personality traits (especially neuroticism) and childhood maltreatment have been independently associated with several negative health outcomes later in life, including migraine [74]. These results are in line with the previous evidence in which personality traits, especially neuroticism, are mediators for the relationship between childhood maltreatment and several mental health variables (i.e., depression, psychological distress, anxiety, substance abuse, alcohol dependence, etc.) [75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83]. In this sense, it has been stated that the presence of an overlap in the neural circuitry underlying experiences of physical pain and social pain (e.g., by childhood maltreatment), and understanding social pain as the painful feelings following social rejection or social loss [84]. There is also evidence of neuroticism as a potential mediator for the relationship between childhood abuse and migraine. These results have been confirmed through direct and indirect statistical analyses [74]. The relationship between migraine/headaches and childhood abuse has been established in large non-clinic-based samples together with several small case control studies using clinic and non-clinic-based sampling frames [85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92].

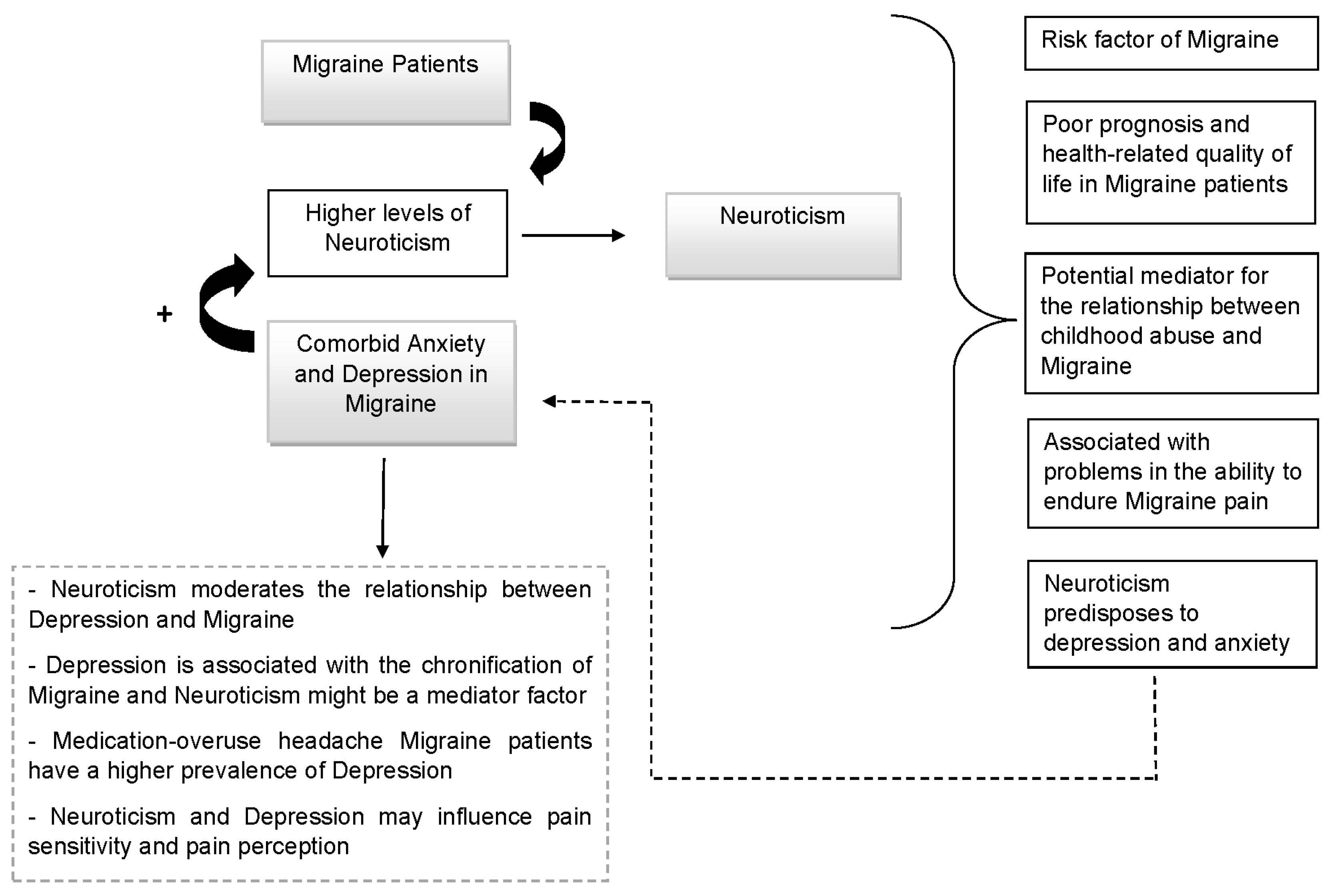

Lastly, it is relevant to mention that neuroticism seems to be also associated with the ability of old women to endure migraine pain [93]. Some authors propose that the theoretical construct of neuroticism implies that people with a high degree of neuroticism are more sensitive and vulnerable to various stimuli, including pain. Therefore, old women with high levels of stress susceptibility and scoring high in somatic trait anxiety experienced more disability during attacks at low levels of migraine pain intensity, showing a vulnerability to migraine pain [93]. At the same time, it is important to note that ageing is characterized by a reduced ability to cope with challenges [94]. Old women with high levels of certain neuroticism-related personality traits showed difficulties in enduring migraine pain, and possibly a reduced ability to cope with the challenge of migraine pain, including pain of mild intensity [93]. Thus, more research is needed in this regard. The relation between neuroticism and migraine is complex and requires us to studied it more widely. Figure 1 (elaborated by authors) shows the above reported most important elements for understanding the relation between migraine and neuroticism.

Figure 1. Migraine and Neuroticism.

References

- Deza, L. La Migraña . Acta Med. Per. 2010, 27, 129–136.

- Loreto, M. Migraña, un desafío para el médico no especialista . Rev. Med. Clin. Condes. 2019, 30, 407–413.

- Pascual, J. Cefalea y Migraña . Medicine 2019, 12, 4145–4153.

- Pérez Pérez, R.; Fajardo Pérez, M.; López Martínez, A.; Orlandi González, N.; Nolasco Cruzata, I. Migraña: Un reto para el médico general integral . Rev. Cubana Med. Gen. Integral. 2003, 19, 1–6.

- Goadsby, P.J.; Evers, S. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society . The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211.

- Steiner, T.J.; Birbeck, G.L.; Jensen, R.; Katsarava, Z.; Martelletti, P.; Stovner, L.J. The Global Campaign, World Health Organization and Lifting The Burden: Collaboration in action. J. Headache Pain 2011, 12, 273–274.

- Galvez-Sánchez, C.M.; Duschek, S.; Reyes Del Paso, G.A. Psychological impact of fibromyalgia: Current perspectives. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 117–127.

- Davydov, D.M.; Galvez-Sánchez, C.M.; Montoro, C.I.; de Guevara, C.M.L.; Reyes Del Paso, G.A. Personalized behavior management as a replacement for medications for pain control and mood regulation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20297.

- Montoro, C.I.; del Paso, G.A.R. Personality and fibromyalgia: Relationships with clinical, emotional, and functional variables. Pers. Individ. 2015, 85, 236–244.

- Eysenck, H.J. Genetic and environmental contributions to individual differences: The three major dimensions of personality. J. Pers. 1990, 58, 245–261.

- Lahey, B.B. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 24156.

- Johnson, M. The vulnerability status of neuroticism: Over-reporting or genuine complaints? Pers. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 877–887.

- Moayedi, M.; Weissman-Fogel, I.; Crawley, A.P.; Goldberg, M.B.; Freeman, B.V.; Tenenbaum, H.C.; Davis, K.D. Contribution of chronic pain and neuroticism to abnormal forebrain gray matter in patients with temporomandibular disorder. Neuroimage 2011, 55, 277–286.

- Affleck, G.; Tennen, H.; Urrows, S.; Higgins, P. Neuroticism and the pain-mood relation in rheumatoid arthritis: Insights from a prospective daily study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1992, 60, 119–126.

- Cao, M.; Zhang, S.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Personality traits in migraine and tension-type headaches: A five-factor model study. Psychopathology 2002, 35, 254–258.

- Mose, L.S.; Pedersen, S.S.; Jensen, R.H.; Gram, B. Personality traits in migraine and medication-overuse headache: A comparative study. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2019, 140, 116–122.

- Mateos, V.; García-Moncó, J.C.; Gómez-Beldarrain, M.; Armengol-Bertolín, S.; Larios, C. Factores de personalidad, grado de discapacidad y abordaje terapéutico de los pacientes con migraña atendidos en primera consulta en neurología (estudio Psicomig) . Rev. Neurol. 2011, 52, 131–138.

- Merikangas, K.R.; Angst, J.; Isler, H. Migraine and psychopathology. Results of the Zurich cohort study of young adults. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1990, 47, 849–853.

- Muñoz, I.; Domínguez, E.; Hernández, M.S.; Ruiz-Piñero, M.; Isidro, G.; Mayor-Toranzo, E.; Sotelo, E.M.; Molina, V.; Uribe, F.; Guerrero-Peral, Á.L. Rasgos de personalidad en migraña crónica: Estudio categorial y dimensional en una serie de 30 pacientes . Rev. Neurol. 2015, 61, 49–56.

- Sevillano-García, M.D.; Manso-Calderón, R.; Cacabelos-Pérez, P. Comorbilidad en la migraña: Depresión, ansiedad, estrés e insomnio . Rev. Neurol. 2007, 45, 400–405.

- Cassidy, E.M.; Tomkins, E.; Hardiman, O.; O’Keane, V. Factors associated with burden of primary headache in a specialty clinic. Headache 2003, 43, 638–644.

- Smith, D.R.; Snell, W.E., Jr. Goldberg’s bipolar measure of the Big-Five personality dimensions: Reliability and validity. Eur. J. Pers. 1996, 10, 283–299.

- McCrae, R. Creativity, Divergent Thinking, and Openness to Experience. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 1258–1265.

- Eysenck, H.J. Personality: Biological foundations. In The Neuropsychology of Individual Differences; Vernon, P.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 151–207.

- Bear, M.F.; Connors, B.W.; Paradiso, M.A. Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain; Wolter Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016.

- Snell, R.S. Clinical Neuroanatomy, 7th ed.; Wolter Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010.

- Kadimpati, S.; Zale, E.L.; Hooten, M.W.; Ditre, J.W.; Warner, D.O. Associations between Neuroticism and Depression in Relation to Catastrophizing and Pain-Related Anxiety in Chronic Pain Patients. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126351.

- Wu, D.; Yin, H.; Xu, S.; Zhao, Y. Risk factors for posttraumatic stress reactions among Chinese students following exposure to a snowstorm disaster. BMC Public Health 2011, 12, 1196.

- Engelhard, I.M.; van den Hout, M.A.; Schouten, E.G. Neuroticism and low educational level predict the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in women after miscarriage or stillbirth. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2006, 28, 414–417.

- Kuljic, B.; Miljanovic, B.; Svicevic, R. Posttraumatic stress disorder in Bosnian war veterans: Analysis of stress events and risk factors. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2004, 61, 283–289.

- Soler-Ferrería, F.B.; Sánchez Meca, J.; López Navarro, J.M.; Navarro Mateu, F. Neuroticismo y trastorno por estrés postraumático: Un estudio metaanalítico . Rev. Esp. Salud. Pública 2014, 88, 17–36.

- Asghari, A.; Nicholas, M.K. Personality and Pain-Related Beliefs/Coping Strategies: A Prospective Study. Clin. J. Pain 2006, 22, 10–18.

- Martínez, M.P.; Sánchez, A.I.; Miró, E.; Medina, A.; Lami, M.J. The relationship between the fear-avoidance model of pain and personality traits in fibromyalgia patients. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2011, 18, 380–391.

- Ramírez Maestre, C.; Esteve Zarazaga, R.; López Martínez, A.E. Neuroticismo, afrontamiento y dolor crónico . An. Psicol. 2001, 17, 129–137.

- Bolger, N. Coping as a personality process: A prospective study. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 525–537.

- Gracely, R.H.; Geisser, M.E.; Giesecke, T.; Grant, M.A.; Petzke, F.; Williams, D.A.; Clauw, D.J. Pain catastrophizing and neural responses to pain among persons with fibromyalgia. Brain 2004, 127, 835–843.

- Galvez-Sánchez, C.M.; Montoro, C.I.; Duschek, S.; Del Paso, G.A.R. Pain catastrophizing mediates the negative influence of pain and trait-anxiety on health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1871–1881.

- Mathur, V.A.; Moayedi, M.; Keaser, M.L.; Khan, S.A.; Hubbard, C.S.; Goyal, M.; Seminowicz, D.A. High Frequency Migraine Is Associated with Lower Acute Pain Sensitivity and Abnormal Insula Activity Related to Migraine Pain Intensity, Attack Frequency, and Pain Catastrophizing. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 489.

- Barral, E.; Buonanotte, F. Catastrofización ante el dolor y abuso de analgésicos en pacientes con migraña crónica . Rev. Neurol. 2020, 70, 282–286.

- Farris, S.G.; Thomas, J.G.; Kibbey, M.M.; Pavlovic, J.M.; Steffen, K.J.; Bond, D.S. Treatment effects on pain catastrophizing and cutaneous allodynia symptoms in women with migraine and overweight/obesity. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 927–933.

- Vallejo-Sánchez, B.; Pérez-García, A.M. Contribución del Neuroticismo, Rasgos Patológicos de Personalidad y Afrontamiento en la Predicción de la Evolución Clínica: Estudio de Seguimiento a los 5 Años de una Muestra de Pacientes con Trastorno Adaptativo . Clin. Salud. 2018, 29, 58–62.

- Kristoffersen, E.S.; Aaseth, K.; Grande, R.B.; Lundqvist, C.; Russell, M.B. Psychological distress, neuroticism and disability associated with secondary chronic headache in the general population-the Akershus study of chronic headache. J. Headache Pain 2018, 19, 62.

- Mccrae, R.R.; John, O.P. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. J. Pers. 1992, 60, 175–215.

- Boz, C.; Velioglu, S.; Ozmenoglu, M.; Sayar, K.; Alioglu, Z.; Yalman, B.; Topbas, M. Temperament and character profiles of patients with tension-type headache and migraine. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2004, 58, 536–543.

- Brandt, J.; Celentano, D.; Stewart, W.; Linet, M.; Folstein, M.F. Personality and emotional disorder in a community sample of migraine headache sufferers. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990, 147, 303–308.

- Breslau, N.; Lipton, R.B.; Stewart, W.F.; Schultz, L.R.; Welch, K.M. Comorbidity of migraine and depression: Investigating potential etiology and prognosis. Neurology 2003, 60, 1308–1312.

- Rasmussen, B.K. Migraine and tension-type headache in a general population: Psychosocial factors. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 21, 1138–1143.

- Sances, G.; Galli, F.; Anastasi, S.; Ghiotto, N.; De Giorgio, G.; Guidetti, V.; Nappi, G. Medication-overuse headache and personality: A controlled study by means of the MMPI-2. Headache 2010, 50, 198–209.

- Sala, I.; Roig, C.; Amador-Campos, J.A.; Garcia-Sanchez, C.; Rodriguez, A.; Diaz, C.; Gich, I. Síntomas psicopatológicos en pacientes afectos de cefalea crónica con o sin fibromialgia . Rev. Neurol. 2009, 49, 281–287.

- Huber, D.; Henrich, G. Personality traits and stress sensitivity in migraine patients. Behav. Med. 2003, 29, 4–13.

- Persson, B. Growth environment and personality in adult migraineurs and their migraine-free siblings. Headache 1997, 37, 159–168.

- Cheng, H.; Treglown, L.; Green, A.; Chapman, B.P.; Κornilaki, E.N.; Furnham, A. Childhood onset of migraine, gender, parental social class, and trait neuroticism as predictors of the prevalence of migraine in adulthood. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 88, 54–58.

- Ligthart, L.; Boomsma, D.I. Causes of comorbidity: Pleiotropy or causality? Shared genetic and environmental influences on migraine and neuroticism. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2012, 15, 158–165.

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Domains and facets: Hierarchical personality assessment using the revised NEO personality inventory. J. Pers. Assess 1995, 64, 21–50.

- Lampl, C.; Thomas, H.; Tassorelli, C.; Katsarava, Z.; Laínez, J.M.; Lantéri-Minet, M.; Rastenyte, D.; Ruiz de la Torre, E.; Stovner, L.J.; Andrée, C.; et al. Headache, depression and anxiety: Associations in the Eurolight project. J. Headache Pain 2016, 17, 59.

- Silberstein, S.D.; Lipton, R.B.; Breslau, N. Migraine: Association with personality characteristics and psychopathology. Cephalalgia 1995, 15, 358–369.

- Svedberg, P.; Bardage, C.; Sandin, S.; Pedersen, N.L. A prospective study of health, life-style and psychosocial predictors of self-rated health. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 21, 767–776.

- Mongini, F.; Ibertis, F.; Barbalonga, E.; Raviola, F. MMPI-2 profiles in chronic daily headache and their relationship to anxiety levels and accompanying symptoms. Headache 2000, 40, 466–472.

- Merikangas, K.R.; Stevens, D.E.; Angst, J. Headache and personality: Results of a community sample of young adults. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1993, 27, 187–196.

- Ashina, S.; Bendtsen, L.; Buse, D.C.; Lyngberg, A.C.; Lipton, R.B.; Jensen, R. Neuroticism, depression and pain perception in migraine and tension-type headache. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2017, 136, 470–476.

- Shiomi, K. Relations of pain threshold and pain tolerance in cold water with scores on Maudsley Personality Inventory and Manifest Anxiety Scale. Percept. Mot. Skills 1978, 47, 1155–1158.

- Goubert, L.; Crombez, G.; Van, D.S. The role of neuroticism, pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in vigilance to pain: A structural equations approach. Pain 2004, 107, 234–241.

- Hall, K.R.; Stride, E. The varying response to pain in psychiatric disorders: A study in abnormal psychology. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1954, 27, 48–60.

- Stengel, E.; Oldham, A.J.; Ehrenberg, A.S. Reactions to pain in various abnormal mental states. J. Ment. Sci. 1955, 101, 52–69.

- Bond, M.R. The relation of pain to the Eysenck personality inventory, Cornell medical index and Whiteley index of hypochondriasis. Br. J. Psychiatry 1971, 119, 671–678.

- Lipton, R.B.; Bigal, M.E.; Ashina, S.; Burstein, R.; Silberstein, S.; Reed, M.L.; Serrano, D.; Stewart, W.F.; American Migraine Prevalence Prevention Advisory Group. Cutaneous allodynia in the migraine population. Ann. Neurol. 2008, 63, 148–158.

- Ashina, S.; Serrano, D.; Lipton, R.B.; Maizels, M.; Manack, A.N.; Turkel, C.C.; Reed, M.L.; Buse, D.C. Depression and risk of transformation of episodic to chronic migraine. J. Headache Pain 2012, 13, 615–624.

- Sair, A.; Sair, Y.B.; Akyol, A.; Sevincok, L. Affective temperaments and lifetime major depression in female migraine patients. Women Health 2020, 60, 1218–1228.

- Breslau, N.; Andreski, P. Migraine, personality, and psychiatric comorbidity. Headache 1995, 35, 382–386.

- Furnham, A. Personality and Intelligence at Work; Routledge: London, UK, 2008.

- Cheng, H.; Furnham, A. Personality, self-esteem, and demographic predictions of happiness and depression. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 921–942.

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979.

- Chan, F.; Cardoso, E.D.S.; Chronister, J.A. Understanding Psychosocial Adjustment to Chronic Illness and Disability: A Handbook for Evidence-Based Practitioners in Rehabilitation; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009.

- Karmakar, M.; Elhai, J.D.; Amialchuk, A.A.; Tietjen, G.E. Do Personality Traits Mediate the Relationship Between Childhood Abuse and Migraine? An Exploration of the Relationships in Young Adults Using the Add Health Dataset. Headache 2018, 58, 243–259.

- Li, X.B.; Wang, Z.M.; Hou, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.T.; Wang, C.Y. Effects of childhood trauma on Headache 15 personality in a sample of Chinese adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2014, 38, 788–796.

- Spinhoven, P.; Elzinga, B.M.; Van Hemert, A.M.; de Rooij, M.; Penninx, B.W. Childhood maltreatment, maladaptive personality types and level and course of psychological distress: A six-year longitudinal study. J. Affect Disord. 2016, 191, 100–108.

- Gamble, S.A.; Talbot, N.L.; Duberstein, P.R.; Conner, K.R.; Franus, N.; Beckman, A.M.; Conwell, Y. Childhood sexual abuse and depressive symptom severity: The role of neuroticism. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2006, 194, 382–385.

- Schwandt, M.L.; Heilig, M.; Hommer, D.W.; George, D.T.; Ramchandani, V.A. Childhood trauma exposure and alcohol dependence severity in adulthood: Mediation by emotional abuse severity and neuroticism. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37, 984–992.

- Hayashi, Y.; Okamoto, Y.; Takagaki, K.; Okada, G.; Toki, S.; Inoue, T.; Tanabe, H.; Kobayakawa, M.; Yamawaki, S. Direct and indirect influences of childhood abuse on depression symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 244.

- Hovens, J.G.F.M.; Giltay, E.J.; van Hemert, A.M.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Childhood maltreatment and the course of depressive and anxiety disorders: The contribution of personality characteristics. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 27–34.

- Martin-Blanco, A.; Soler, J.; Villalta, L.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Elices, M.; Pérez, V.; Arranz, M.J.; Ferraz, L.; Alvarez, E.; Pascual, J.C. Exploring the interaction between childhood maltreatment and temperamental traits on the severity of borderline personality disorder. Compr. Psychiat. 2014, 55, 311–318.

- Vinkers, C.H.; Joels, M.; Milaneschi, Y.; Kahn, R.S.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Boks, M.P.M. Stress exposure across the life span cumulatively increases depression risk and is moderated by neuroticism. Depress. Anxiety 2014, 31, 737–745.

- Brents, L.K.; Tripathi, S.P.; Young, J.; James, G.A.; Kilts, C.D. The role of childhood maltreatment in the altered trait and global expression of personality in cocaine addiction. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 64, 23–31.

- Eisenberger, N.I. The neural bases of social pain: Evidence for shared representations with physical pain. Psychosom. Med. 2012, 74, 126–135.

- Gelaye, B.; Do, N.; Avila, S.; Carlos Velez, J.; Zhong, Q.Y.; Sanchez, S.E.; Peterlin, B.L.; Williams, M.A. Childhood abuse, intimate partner violence and risk of migraine among pregnant women: An epidemiologic study. Headache 2016, 56, 976–986.

- Tietjen, G.E.; Brandes, J.L.; Peterlin, B.L.; Eloff, A.; Dafer, R.M.; Stein, M.R.; Drexler, E.; Martin, V.T.; Hutchinson, S.; Aurora, S.K.; et al. Childhood maltreatment and migraine . Emotional abuse as a risk factor for headache chronification. Headache 2010, 50, 32–41.

- Juang, K.D.; Wang, S.J.; Fuh, J.L.; Lu, S.R.; Chen, Y.S. Association between adolescent chronic daily headache and childhood adversity: A community-based study. Cephalalgia Int. J. Headache 2004, 24, 54–59.

- Fuller-Thomson, E.; Baker, T.M.; Brennenstuhl, S. Investigating the association between childhood physical abuse and migraine. Headache 2010, 50, 749–760.

- Fuh, J.L.; Wang, S.J.; Juang, K.D.; Lu, S.R.; Liao, Y.C.; Chen, S.P. Relationship between childhood physical maltreatment and migraine in adolescents. Headache 2010, 50, 761–768.

- Tietjen, G.E.; Buse, D.C.; Fanning, K.M.; Serrano, D.; Reed, M.L.; Lipton, R.B. Recalled maltreatment, migraine, and tension-type hedache: Results of the AMPP study. Neurology 2015, 84, 132–140.

- Brennenstuhl, S.; Fuller-Thomson, E. The painful legacy of childhood violence: Migraine headaches among adult survivors of adverse childhood experiences. Headache 2015, 55, 973–983.

- Tietjen, G.E.; Karmakar, M.; Amialchuk, A.A. Emotional abuse history and migraine among young adults: A retrospective cross-sectional analysis of the add health dataset. Headache 2017, 57, 45–59.

- Mattsson, P.; Ekselius, L. Migraine, major depression, panic disorder, and personality traits in women aged 40–74 years: A population-based study. Cephalalgia 2002, 22, 543–551.

- Masaro, E.J. (Ed.) Ageing: Current concepts. In Handbook of Physiology, Section 11: Ageing; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 3–33.

More