The goal of this paper is to review the intertwined range of conceptualizations that have blurred developing knowledge regarding environmental sustainability. An examination of the leadership literature reveals differential descriptions about sustainable, environmental, and sustainability leadership which are increasingly being used to imply what sustainability-focused leaders do, their interactions, their relationships, and how they address sustainable challenges. While extant research supports that leadership is a critical capability to respond and adapt to constant external environmental and economic upheaval in large firms, agreement about the types of leadership practices necessary to achieve positive environmental sustainability and eco-efficient outcomes is less clear in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). To resolve these problems, researcherswe synthesize the sustainable, environmental and sustainability leadership literature by (a) reviewing and clarifying these leadership constructs, (b) theoretically unravelling these overlapping concepts, and (c) developing an integrated framework of intellectual capital and sustainability leadership practices. The entrypaper is designed to advance a new way of thinking about sustainability leadership by presenting an original contribution that alters and reorganizes potential causal maps, that are potentially more valuable. Whilst most of the leadership research involves large firms, researcherswe seek to better understand and inform sustainability leadership in SMEs.

1. Introduction

Research on sustainability leadership in SMEs is important as there is a growing awareness within the SME literature that traditional operating procedures incurring high energy and water consumption costs, minimal recycling, and generation of considerable waste (among others) are no longer sustainable

[1][2][1,2]. More than 70 years ago, Stogdill

[3] noted that the study of leadership is an analysis of relationships and that all organizations operate within a large cultural and environmental framework. The objectives of organizations should be to maximise social values relative to the limited resources available

[3][4][3,4]. For contemporary scholars, there is increasing interest and strategic concern to reduce and recycle waste, use less energy and water, develop new products or services, and to create efficiencies and increase innovation

[5][6][5,6]. SME leaders are in a powerful position to promote positive environmental sustainability and eco-efficient outcomes in their firms. Indeed, leaders and leadership are a ‘key interpreter’ of how organizations respond to environmental challenges

[7]. Although there is an emerging leadership literature describing sustainable, environmental and sustainability leadership in the education sector

[8][9][8,9], large companies

[10][11][12][10,11,12], and government

[13], many extant studies only take the narrative related to SME sustainability leadership so far. Whilst leadership is considered an important capability to respond and adapt to external environmental and economic fluctuations

[14], there is a lack of agreement and understanding about the types of leadership necessary for positive environmental sustainability

[7][15][16][7,15,16]. What is missing in leadership literature is a theoretical framework that provides a new way of thinking about existing sustainability leadership dimensions. This is important in the study of sustainability leadership since scholars and practitioners are often no wiser about which leadership behaviours best suit eco-efficient outcomes and sustainable practices. It is particularly important for SME leaders who lack the necessary knowledge, capital, and resources to address and implement sustainability initiatives

[17][18][17,18]. Thus, the aim of this paper is to classify the emerging leadership skills and knowledge necessary to achieve improved SME environmental performance.

While the sustainability literature is one of the most interesting fields of scholarly inquiry related to achieving eco-efficient outcomes, specific knowledge about sustainability leadership practices and skills is not well defined across industry settings and within knowledge domains

[12][19][12,19]. General descriptions about sustainable, environmental, and sustainability leadership are increasingly being used to imply what sustainability-focused leaders do, their interactions, their relationships, and how they address complex sustainable challenges, even while the contexts in which leaders operate are difficult and complex

[20][21][20,21]. While leadership is considered an important capability to respond and adapt to external environmental and economic fluctuations

[14][22][14,22], agreement about the types of leadership practices necessary to achieve positive environmental sustainability is less transparent

[7][12][16][7,12,16]. Scholars note that sustainability challenges require new leadership skills and practices that ‘help support managers to become effective sustainability leaders in their organizations’

[12]. Accordingly, this review seeks to expand relative scientific contribution by drawing upon a range of theoretical ideas, and the most pervasive leadership skills and practices relevant within a leadership domain. Here, the review is designed to provide more revelatory value by improving the classification and compilation of leadership skills and behaviours by elevating their utility within an SME context.

While extant studies examining leader practices have been linked to sustainability

[7][23][7,23], environmental leadership practice

[24], and sustainable productivity outcomes

[10][22][24][10,22,24], few clear links exist between leadership practice cause and effect in respect of sustainable outcomes more generally. Thus far, scholars use sustainable, environmental, and sustainability terminologies interchangeably, yet this often creates confusion in the literature, making it more difficult for scholars and practitioners to identify which sustainability leadership practices are more germane within a given context

[20][25][26][20,25,26]. In order to make sense of the literature and to clarify often contradictory terms, this paper offers a framework that provides a nuanced understanding of the practices relating to sustainability leadership.

Different leadership practices do not only reflect individual-level leadership attributes, but also organization-level practices embedded as structures, systems, and routines as mechanisms to create change. A typical example of structures and systems is sustainable production processes to reduce waste or technological structures to reduce emissions. These structures potentially create innovation

[27][28][27,28]. Organizations design structures and systems to create institutional knowledge that increases the organizational capacity

[29][30][29,30] of leaders to respond to environmental challenges necessary to guide how the organization itself learns

[31][32][31,32], including knowledge about how different aspects of organization design have an important mediating influence on environmental management

[33]. As an organization-level attribute, sustainable structures and systems will need to reflect what leaders pay attention to

[34], including the routines that are created that lead to sustainable knowledge creation

[35][36][35,36]. Within the existing literature on sustainability leadership, it is less clear how these structures and systems are created to support sustainable innovations in general.

Similarly, how SMEs introduce sustainability measures by creating strong internal and external network capital linkages needs to be better understood

[37]. Social capital buttresses the development of social relationships

[38], where social relationships comprise of both internal and external social capital that provide linkages between individuals and external firms

[39]. Social capital more generally refers to the ‘ability of actors to secure benefits by virtue of membership in social networks or other social structures’

[40]. External relationships refer to networks established among external actors

[38][41][42][38,41,42], that together lead to network capital benefits such as co-created knowledge routines through leadership experience ties

[43][44][43,44]. This involves an affinity between individual and organization-level leadership attributes with a priority to establish social, as well as organization capital

[39][45][39,45]. Since sustainability is concerned about the impact of decisions on the natural environment, leaders need to work more closely within and across networks.

2. Sustainable, Environmental and Sustainability Leadership

There is a significant body of literature related to the functions of sustainable, environmental, and sustainability leadership over the last 30 years. Extant research treats these as separate bodies of literature, yet while the embodiment of functions and processes could be deemed as dissimilar, fine nuances and complementary characteristics exist with respect to leadership practices. Sustainable leadership (SL) is often described in terms of being socially and environmentally responsible, preserving and sustaining the environment, and as a shared responsibility between both internal and external players as they plan for long-term sustainable goals

[4][10][23][4,10,23]. Similarly, environmental leadership (EL) relies on practices that care for and protect the natural environment such as the deep-seated values and beliefs of organizations and the moral commitment of its members towards achieving a sustainable outcome

[22][46][22,47]. Slightly different is sustainability leadership (ST-L). Here, it is about anyone who takes responsibility for acting on sustainable challenges including but not limited to initiating and influencing change towards some sustainable future

[16][47][16,48]. Similarly, for ST-L, setting direction while simultaneously creating organizational alignment underpins a commitment towards employee and stakeholder buy-in

[48][49]. Interestingly, leadership practice becomes critical for SL, EL, and ST-L practices, such as establishing a creative culture that enables the organization to learn new things and increase its innovative processes

[7][25][7,25].

Leadership practices more generally underpin the nuanced differences between the three definitions. At their most basic, leadership practices involve key knowledge, skills, and abilities that comprise the

individual-level attributes of individual leaders

[49][50][51][50,51,52]. First, practices related to developing SL skills pertains to the cognitive antecedents of leaders, namely establishing a mindset for innovation, creating shared responsibility and passion between stakeholders, and developing the motivation towards achieving sustainable goals

[8][9][10][52][8,9,10,53].

RWe

searchers call these

innovation and relational practices. Second, practices related to EL pertains to an embedded personal moral imperative towards protecting the environment, identifying individual and organizational levels of influence, and establishing a set of sustainable personal values and norms

[24][46][52][53][24,47,53,54].

ThWe

y call these

ideological and moral practices. Lastly, practices related to ST-L pertain to what leaders do in relation to direction-setting and top management commitment, relational-oriented practices, and task-oriented practices towards developing action plans, aligning goals, and dealing with complex internal and external environmental adaptation

[51][54][55][52,55,56].

ThWe

y call these

strategic adaptation practices.

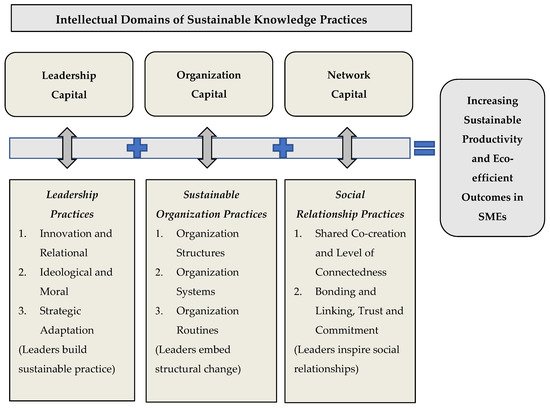

In sum, these leadership practices underpin what leaders do, the tasks and functions that guide action to build environmentally sustainable outcomes (ESO) within the SME context and form the basis of the theoretical framework (

Figure 1). What is illustrated in

Figure 1 is that leadership capital does not stand in isolation of other sustainable knowledge practices, which are explained in more detail later in this review paper.

TheiOur research suggests that leadership will occur not only at the individual level but will necessitate integration with sustainable practices at the organization and network capital level. For instance, sharing positive change and building environmental norms will almost certainly be fashioned at the organizational level

[56][57], while mobilizing employees is not only an individual skill but also an organizational process that helps establish long-term ecological goals

[57][58]. Similarly, the idea of co-creation within the sustainability literature involves moving beyond individual social relations to forging value-chain based production processes

[35], as well as the self-development of actors (SME Leaders) networking, collaborating, and forming ecosystems that support sustainable productivity goals

[58][59]. Co-creation itself appears to invoke a set of leadership practices focused on the creation of an integrated network of suppliers, vendors, and customers

[48][49]. In sum, the theoretical framework is a new approach aimed at bringing to the forefront many leadership skills and practices in SMEs.

Figure 1. An intellectual capital framework of sustainability leadership in SMEs. Source: Authors.

For the first of the sustainable knowledge practices presented in

Figure 1, the separate but related bodies of sustainable and environmental leadership practice are transitioned into one generic term, that is, sustainability leadership (ST-L hereafter). This review thus seeks to address what studies appear to describe as separate leadership practices by clarifying that, collectively, such practices are complementary and integrated individual-level leadership attributes. This is similar to how complementarity is described within the human capital resource (HCR) literature, where an ‘employee and the firm possess distinct HCR that, when combined, have the potential to create an amount of value that is greater than the sum of the individual parts’

[59][60].

While nuanced differences can be observed in the three approaches, it makes little sense to separate the practices of leaders across similar sustainability tasks. Thus,

rwe

searchers provide greater clarity of the relationship between ST-L and how to achieve environmentally sustainable and eco-efficient outcomes based on what leaders do by exploring which leadership practices are more germane within a given ST-L context. Accordingly, ST-L is the basis of leadership practices (see

Figure 1) and is discussed in more detail next. An analysis and summary of extant research that informs the relationships in

Figure 1 is outlined in

Table 1 as follows.

Table 1. Summary of extant research in intellectual domains of sustainable knowledge practices.

| Leadership Capital—Leadership Practices |

| Emerging Concepts |

References |

Summary of Key Findings |

|

|

- 1.

-

Innovation and Relational Leadership Practices

|

|

Burns, 1978; Yukl et al., 2002; Hargreaves and Fink, 2006; Ferdig, 2007; Crews, 2010; Avery and Bergsteiner, 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Tildeman et al., 2013; McCann and Sweet, 2014; Burns et al., 2015; Behrendt et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2017; Robertson and Barling, 2017; Robertson and Carleton, 2018; Yukl et al., 2019; Fry and Engel, 2021. Prasanna et al., 2021. |

|

- -

-

Components of transformational leadership are most effective to promote sustainability and is a shared responsibility

- -

-

Requires a long-term perspective in decision making fostering innovation and building continuous improvement, creation of opportunities for people to come together to generate their own answers

- -

-

An integrated effort that requires communication among various stakeholders, collaboration, inclusiveness, relationships, and common purpose are components in engaging pro-environmental behaviours, commitment towards a more balanced approach considering the triple bottom line, motivation, and extraordinary decision making and problem-solving skills are required

- -

-

Leaders concerned with people and the environment will support stakeholders that represent the best interests of people and the planet

|

|

|

|

- 2.

-

Ideological and Moral Leadership Practices

|

|

Shamir et al., 1993; Egri and Frost, 1994; Flannery and May, 1994; Robinson and Clegg, 1998; Conger, 1999; Hargreaves and Fink, 2006; Svensson and Wood, 2007; Egri and Herman, 2000; Boiral et al., 2014; Deinert et al., 2015; Burns et al., 2015; Tajason et al., 2015; Adams et al., 2016; Jang et al., 2017; Vasquez et al., 2019. |

|

- -

-

Sustainability leadership is founded on a moral purpose, are more aware of eco-centric values, develop an ecological vision and are personally committed to reduce or prevent pollution

- -

-

Moral norms, values and environmental attitudes are factors influencing top managers

- -

-

Strategies devised that improve competitive advantage about caring for the environment

- -

-

Leadership ethics is a continual and iterative process and personal values are strongly concerned with the welfare of others and the environment

|

|

|

|

- 3.

-

Strategic Adaption Leadership Practices

|

|

Boal and Hooijberg, 2000; Van Velsor and McCauley, 2004; Jansen et al., 2009; Quinn and Dalton, 2009; Battilana et al., 2010; Hsu and Wang, 2012; Adams et al., 2016; Arnold, 2017; Carro-Suarez et al., 2017; Kurucz et al., 2017; Nui et al., 2018; Vasquez et al., 2019; Yukl et al., 2019. |

|

- -

-

Transformational and relational, transactional and task leadership and change leadership behaviours are important strategic leadership practices for pro-environmental initiatives, and are related to managerial effectiveness and strategic sustainability

- -

-

Tasks such as setting direction, creating alignment, and maintaining commitment are required, as well as developing actions plans, communicating, making decisions and solving problems, deploying resources, and driving change that requires action to be taken on sustainability values.

- -

-

Making intentional changes to an organization’s mission and values leads to changed products, processes or practices that create environmental value

- -

-

Co-creation is a way of sharing, combining and renewing resources, knowledge and ideas to create value through new forms of interaction, service and learning

- -

-

Sustainability strategies and environmental practices help to decrease their negative impact and promote cost effectiveness

|

|

| Organization Capital—Sustainable Organizational Practices |

| Emerging Concepts |

References |

Summary of Key Findings |

|

|

- 4.

-

Organization

Structures

- 5.

-

Organization Systems

- 6.

-

Organization Routines

|

|

Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Helfat, 1997; Robinson and Clegg, 1998; Johnson, 1999; Bontis and Fitz-enz, 2002; Zahra and George, 2002; Marr, 2004; Youndt, 2005; Cohen and Kaimenakis, 2007; Ferdig, 2007; Timmer et al., 2007; Epstein, 2008; Stahle, 2008; Quinn and Dalton, 2009; Crews, 2010; Epstein et al., 2010; Clarke et al., 2011; Arora and Nandkumar, 2012; Hsu and Wang, 2012; Tideman et al., 2013; Benn et al., 2014; Hu and Randel, 2014; Murray, 2018; Pertusa-Ortega et al., 2018; Yukl et al., 2019; Kantabutra, 2020. |

|

- -

-

Creation of structures that support the vision and mission of sustainability

- -

-

Embedding sustainability in business structures by establishing policies, procedures and innovative organizational designs—including effective team structures

- -

-

Commitment, communication (including speeding the flow of knowledge routines), organization, control and monitoring (continuous improvement and planning are essential) in managing and reporting sustainable productivity

- -

-

Leaders must pay attention to regulations, legal obligations, and shareholder activism

- -

-

The importance of soft/informal systems and processes are just as important as formal systems that measure and reward performance towards sustainable productivity goals

- -

-

Goal clarity, delegating, and the ability to monitor and evaluate eco-efficient change processes

|

|

| Network Capital—Social Relationship Practices |

| Emerging Concepts |

References |

Summary of Key Findings |

|

|

- 7.

-

Shared

Co-creation and Level of Connectedness

- 8.

-

Bonding and Linking, Trust and Commitment

|

|

Baker, 1990; Flannery and May, 1994; Coleman, 1988; Robinson and Clegg, 1998; Johnson, 1999; Bontis and Fitz-end, 2002; Adler and Kwon, 2002; Boiral et al., 2009; Quinn and Dalton, 2009; Crews, 2010; Manning, 2010; Avery and Bergsteiner, 2011; Clarke et al., 2011; Hsu and Wang, 2012; Tideman et al., 2013; Benn et al., 2014; Boiral et al., 2014; Costa et al., 2014; Whipple et al., 2015; Arnold, 2017; Etzion et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2017; Behrendt et al., 2017; Pillai et al., 2017; Bontis et al., 2018; Wang and Cotton, 2018; Burlea-Schiopoiu and Mihai (2019); Redondo and Camerero, 2019; Haney et al., 2020; Fry and Egel, 2021; Tolstykh et al., 2021. |

|

- -

-

Teamwork (including employee contributions) and an ability to mobilise employees around long-term ecological goals, thus developing co-creation of ideas

- -

-

Focus on stakeholder engagement and creating a culture that is integrated resulting in a sharing approach

- -

-

Building strong social relationships (both internal and external) and recognising interdependence, interconnectedness, continuity and common purpose of all stakeholders both long and short-term influencing and collaborating, building trust and establishing fairness

- -

-

Developing an understanding, personal connection and empowerment to act for sustainability

- -

-

Learning, lobbying, and forming alliances with a focus on communication

- -

-

Application of an ecosystem model that makes it possible to form a friendly environment where the goals of all stakeholders aiming to achieve sustainable productivity are harmonised

|

|