Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jason Zhu and Version 1 by Narcisa Tribulova.

Oxidative stress and inflammation are deleterious to cardiovascular health, and can increase heart susceptibility to arrhythmias. It is quite interesting, however, that various cardio-protective compounds with antiarrhythmic properties, including sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and statins, are potent anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory agents.

- inflammation

- oxidative stress

- cardiac arrhythmias

- SGLT2i

- statins

1. Antiarrhythmic Efficacy of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors (SGLT2i) Inhibitors

The sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) increase glucose excretion by blocking kidney reabsorption. Therefore, SGLT2i such as empagliflozin are efficacious in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [108][1]. T2DM is accompanied by low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress and independently associated with AF [109][2]. T2DM forms part of the metabolic syndrome cluster which includes obesity and hypertension. Of note, body weight loss following SGLT2i treatment has been associated with a lower risk of new-onset AF in patients with T2DM [110][3]. In addition, meta-analysis suggests that epicardial fat is significantly reduced in T2DM patients with SGLT2-i treatment [111][4]. While epicardial fat is known to promote AF or VF due to the activation of inflammasome and production of cytokines [38,39,112][5][6][7]. Advanced glycation end-products and activation of their receptors may also confer a signaling mechanism for diabetes-related AF [113][8]. The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial recorded that patients with T2DM and AF may especially benefit from the use of empagliflozin [114][9] and SGLT2i were associated with a lower risk of new-onset AF in T2DM patients compared to the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor [115][10]. In addition, a large pharmaco-vigilance database highlighted that AF occurred more frequently in diabetes when medications other than SGLT2i were used [116][11]. Therefore, SGLT2i may confer a specific AF or atrial flutter-reduction benefit not only in T2DM patients but also in high risk populations [117,118][12][13]. The treatment with SGLT2i also significantly reduced the development of new-onset AF in the T2DM patients who had non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy [119][14].

In addition, SGLT2i treatment was associated with the reduction of new-onset HF and cardiovascular mortality [120][15]. The cardioprotective effect of SGLT2i was independent of glycemic control, diabetes or a reduction in traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Moreover, the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial showed a 19% AF reduction in DM patients with SGLTi treatment, regardless of pre-existing AF or HF [121][16]. These findings complement available evidence from trials supporting protective SGLT2i pleiotropic effect against the occurrence of AF. SGLT2i also reduced the risk of cardiac arrhythmias in patients with DM, HF and chronic kidney disease [122,123][17][18].

Moreover, dapagliflozin SGLT2i reduced the risk of serious VT or VF, cardiac arrest or SCD when combined with conventional therapy in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction [124][19]. However, further research is still needed to determine overall risk of SCD and ventricular arrhythmias in patients with T2DM and/or HF treated with SGLT2i [125][20]. Suppressed ventricular ectopic burden after 2-weeks treatment with dapagliflozin suggests early antiarrhythmic benefit in patients suffering from HF with reduced ejection fraction [126][21]. There is also direct evidence decoding the effects of SGLT2i on ventricular arrhythmias in HF [127[22][23][24],128,129], and also reversion of cardiac remodeling and improved cardiac function [130,131][25][26]. Nevertheless, future studies are required to elucidate mechanistically cardiovascular benefit of SGLT2i for more specific targeting of HF therapy [20][27].

Single empagliflozin dose was well tolerated by healthy volunteers, and it was not associated with QTc prolongation [132][28]. Ongoing experimental studies suggest that SGLTi not only attenuates HF but also counteracts cellular ROS production in cardiomyocytes, thereby potentially hampering myocardial remodeling and reducing AF and VF burden. This important feature of SGLT2i is linked to their impact on redox signaling in AF, and this has recently been comprehensively reviewed [133][29]. SGLT2i also exerts direct anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effects on resting endothelial cells, and its anti-oxidative effect could be partly mediated by NADPH oxidase inhibition [134][30]. Moreover, chronic SGLTi treatment has been shown to protect diabetic mice from inflammation [135][31]. These cardioprotective effects appear to be associated with the increased ketone bodies which are acknowledged modulators of inflammation by inhibiting NLPR3 inflammasome and oxidative stress through protective mitochondria function [136][32]. It is note-worthy that SGLT2i reduced the inflammation and ameliorated clinical outcomes at the five-year follow-up of T2DM patients who had coronary artery bypass grafts [137][33].

These clinical and experimental studies further suggest that SGLT2i’s have anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative potential, and that they reduce both blood glucose and cardiac arrhythmia risks. It is therefore highly likely that prevention and/or attenuation of myocardial inflammation and oxidative stress results in the suppression of pro-arrhythmogenic factors due to SGLT2i preservation of ion channels and Ca2+ handling. Finally, cardiologists would really appreciate a practical guide that ensures greater understanding of when, how and to whom SGLT2i should be prescribed.

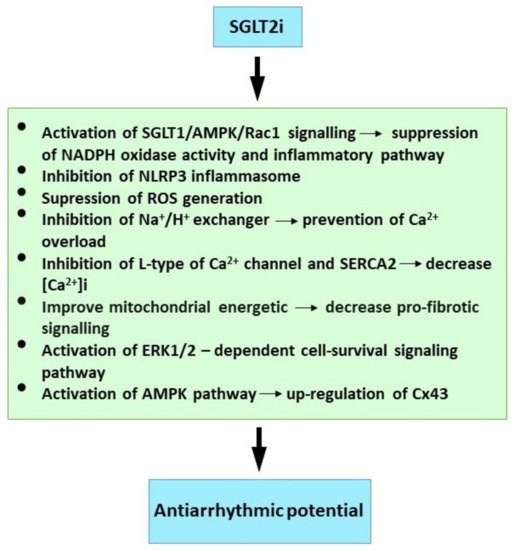

Mechanisms Relevant to Antiarrhythmic Properties of SGLT2 Inhibitors

Post-ischemic empagliflozin treatment in animal studies was associated with decreased VF induction [65][34]. This antiarrhythmic effect was linked with improved myocardial redox state and cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics. The modification of diastolic Ca2+ and cardiac alternants may be responsible for the reduced ventricular arrhythmia. There was also improved mitochondrial respiratory chain function. This respiration complex II contributes to empagliflozin’s post-ischemic cardio-protection from infarction [138][35], and empagliflozin pre-treatment protects the heart from lethal ventricular arrhythmia induced by myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. These protective benefits may occur as a consequence of activation of the ERK1/2-dependent cell-survival signaling pathway in a glucose-independent manner [139][36]. It is further reported that dapagliflozin attenuated vulnerability to arrhythmia due to ROS suppression and Cx43 up-regulation through the AMP-activated protein kinase pathway in post-infarct rat hearts [140][37]. Canagliflozin suppressed myocardial NADPH oxidase activity and improved NOS coupling via SGLT1/AMPK/Rac1 signalling, leading to global anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects in the human myocardium [21][38].

Blood glucose concentrations greater than 270 mg/dL (15 mmol/L) lead to QT/QTc prolongation and also reduction in potassium IKr [141][39]. While dapagliflozin suppressed prolonged ventricular-repolarization in insulin-resistant metabolic syndrome rat models [142][40]. Acute dapagliflozin administered to rats prior to cardiac ischemia had cardio-protective effects by attenuating infarct size, increasing ventricular function, reducing the arrhythmia score and prolonged time to VT/VF onset [143][41]. Dapagliflozin also suppressed cardiac fibrosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress and improved hemodynamics in the HF rat model [144][42]. In addition, empagliflozin prevented sotalol-induced QT prolongation. This was most likely achieved by regulating the intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ balance, and possibly promoting potassium (IKr) channel activation [145][43]. Moreover, empagliflozin has been shown to modulate Ca2+ handling by lowering cytosolic Na+ and Ca2+ through inhibition of the Na+/H+ (NHE1) exchanger and the Ca2+ L-type channel and SERCA2a, combined with modulation of electrophysiological APD and QT interval shortening [146,147,148][44][45][46]. The salutary effects of SGLT2i on Na+ homeostasis by influencing NHE1 activity, and the late INa and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) activity have been comprehensively discussed [149][47].

Empagliflozin significantly shortened the QT, attenuated the down-regulation of myocardial Cx43 expression and reduced fibrotic areas in the ventricles of mice with metabolic syndrome [150][48]. The combined sotagliflozin SGLT1-2i ameliorated atrial remodeling in a rat model with metabolic syndrome-related to HF with preserved ejection fraction [151][49], and it also suppressed Ca2+-mediated in-vitro cellular arrhythmogenesis. This included the magnitude of spontaneous arrhythmic Ca2+ release, mitochondrial Ca2+ buffer capacity and diastolic Ca2+ accumulation. This was most likely achieved by increased Na+/Ca2+ exchanger forward-mode activity. The over-expression and Ca2+-dependent activation of CaMKII are hallmarks of HF. This leads to contractile dysfunction and arrhythmias. In addition, empagliflozin reduced CaMKII activity, and the CaMKII-dependent SR Ca2+ leak and improved Ca2+ transients may contribute to antiarrhythmic and contractile functions which enhance the empagliflozin effect in HF [152][50].

Atrial structural and electrical remodeling also facilitate AF development. Canagliflozin suppressed oxidative stress and interstitial fibrosis with improved effective refractory period and conduction velocity in the rapid-pacing dog model [153][51]. In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction drives structural, electrical and myocardial tissue contractile remodeling in pathophysiological settings. Here, the empagliflozin ameliorated inflammatory burden and atrial fibrosis in T2DM rats, and also improved their mitochondrial function and reduced inducible AF [154][52]. Empagliflozin has been reported to maintain mitochondria related cellular energetics and afford its benefits against developing adverse remodelling in post-infarction mice [23][53].

Available findings imply that SGLTi may affect Ca2+ handling, Na+ balance and mitochondrial ROS release. However, further research is required to elucidate SGLT2i’s protective mechanism against cardiac arrhythmias. Finally, although evidence from clinical trials and experimental studies on the molecular mechanisms is compelling (Figure 1), early trials designed specifically for SGLT2i antiarrhythmic efficacy will be welcome, and these should prove informative.

2. Antiarrhythmic Efficacy of Statins

Statins as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors are current first-line therapy in dyslipidemia disorders. Statins lower undesirable lipid-levels and thereby reduce cardiovascular mortality. Statins also exert anti-inflammatory, anti-ischemic, antioxidant and autonomic nervous system modulation [155,156][54][55] and they have been shown to suppress toll-like receptors and cytokine expression both in vitro and in vivo. For example, simvastatin reduced circulating TNF-α and MCP-1 in healthy male volunteers [157][56], and atorvastatin reduced the TNF-α, IL-1b, and IL-6 levels in hypercholesterolemic patients [158][57]. It is also important that statins suppressed the NLRP-3 inflammasome pathway [159][58] and up-regulated the cytokine signaling-3 plasma suppressor [160][59]. Statin therapy was associated with suppression of microbiota dysbiosis [161][60], which generates pro-inflammatory metabolites promoting arrhythmias [42][61].

In addition, the statins reduce VT, VF and SCD incidence and AF occurrence. This is attributed to their pleiotropic effects [155][54]. Statin use in adjunct therapy lowered mortality in patients with HF originating from any cause, and also those with VT [162,163,164][62][63][64] and SCD due to malignant VT/VF [164,165,166,167][64][65][66][67]. Statins are associated with significant reduction in VT in cardiomyopathy patients with implanted cardioverter defibrillators [168][68] and myocardial infarction [169[69][70],170], and they also reduced postoperative cardiac arrhythmia in patients undergoing arthroplasty [171,172][71][72]. Authors further reported that atorvastatin treatment; (1) improved heart rate variability in persons with sleep deprivation [173][73]; (2) reduced occurrence of exercise-induced premature ventricular contractions [155][54] and (3) decreased occurrence of post-cardiac surgery-associated AF (POAF) [174,175,176][74][75][76]. However, further studies are required to find the most effective statin regimen for POAF prevention with the highest health benefits [177][77]. Statin therapy prevented post-reperfusion atrial nitroso-redox imbalance in patients on pump-cardiac surgery [22][78].

The combination of atrial remodeling and ROS suppression may explain why statins are effective in primary AF prevention [178][79]. For example, the P-wave dispersion use for AF prediction was lower in cryptogenic stroke patients previously treated with statins [179][80], and this dispersion correlated with highly-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP)levels. These reflect inflammation’s role in promoting the slowed and inhomogeneous atrial conduction. Short-term intensive statin therapy reduced the volume of epicardial adipose tissue which is recognized as a pro-inflammatory marker in AF patients [112][7].

Rosuvastatin reduced autonomic nerve-sprouting combined with decreased mRNA and tyrosine hydroxylase protein expression levels in atrial tissues following acute myocardial infarction [180][81]. These findings provide understanding of the mechanism statins use to decrease the risk of AF occurrence after heart attack.

Statin use was also associated with lower AF recurrence rate after treatment using catheter ablation of the triggers [181][82]. A future systematic review and network meta-analysis on statin effects in preventing AF recurrence should provide comprehensive evidence-based proof in clinical practice [182][83]. Statins could therefore be a novel strategy to prevent AF occurrence in patients with pacemakers, and especially those with sinus node dysfunction [183][84]. The AF risk associated with premature atrial complexes in patients with hypertension could potentially be reduced by treatment with statins [184][85]. In addition, a nation-wide study has established that statins reduced new-onset AF after acute myocardial infarction [185][86].

Statins also attenuated circadian variation in QTc dispersion, and they reduced this pro-arrhythmic parameter in diabetic patients and those who had myocardial infarction [155,186,187][54][87][88]. Statins were also suggested as an adjuvant therapy in reducing AF and VF burden in various clinical settings [188[89][90],189], and preoperative statin treatment was shown to reduce VF development and decrease C-reactive protein levels in post-surgery patients [190][91].

The statin antiarrhythmic potential has been demonstrated in experimental studies. Acute administration of atorvastatin reduced rat heart susceptibility to VF, and long-term atorvastatin treatment was efficacious in rats suffering hereditary hypertriglyceridemia [191,192][92][93]. In addition, spontaneous VF during ischemia-reperfusion was suppressed by rosuvastatin [193][94]. Moreover, the following atorvastatin effects have also been noted; (1) atorvastatin protected the rat myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion induced arrhythmias [194,195][95][96]; (2) it ameliorated rat cardiac sympathetic nerve remodeling and prevented VT/VF following myocardial infarction, and it down-regulated IL-1β and TNF-α expression [196][97]; (3) its antiarrythmia effects may also be due to IL-1β and IL-6 suppression in ouabain-induced rat arrhythmias [197][98] and (4) it reduced elevated hs-CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α which correlate with longer effective refractory period in the sterile-goat pericarditis model [198][99]. In contrast, non-treated peri carditis animals had a longer AF duration than the treated group. Anti-inflammatory and anti-ischemic effects form the likely mechanism for the reduced SCD with statin use [155][54].

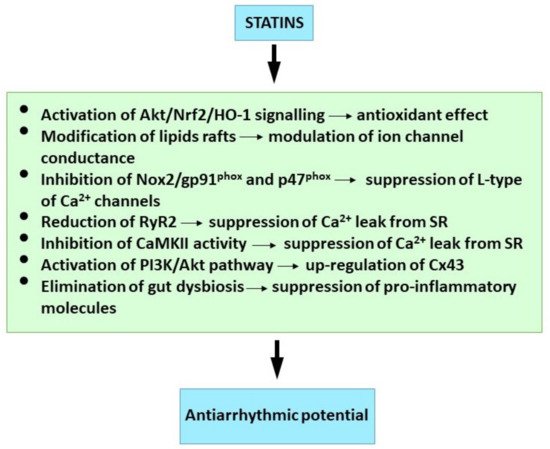

Mechanims Relevant to Statins Antiarrhythmic Properties

Although it has been hypothesized that statins alter the cardiac cell lipid membrane for transmembrane ion channel penetration, the precise statinVT/VF and SCD reduction mechanism has not been established. The penetration may occur by statin-induced modification of lipid rafts which are membrane micro-domains containing signaling molecules and ion channel regulatory proteins [199,200,201][100][101][102]. Thus, statins may directly reduce arrhythmias by favorably altering ion channel conductance. Statins have been shown to reduce hypercholesterolemia and ischemia-reperfusion-induced electrophysiological remodeling in animal models [169[69][103],202], and statin’s pleiotropic effects may be due to the inhibition of isoprenoid intermediates [203][104], because isoprenoid inhibits the Rac and Rho GTP binding proteins. Targeting down-stream Rho kinase could be a predominant mechanism in statin antiarrhythmic effects.

Atorvastatin blocks increased L-type Ca2+ current and myocardial cell injury induced by angiotensin II through the inhibition of ROS mediated Nox2/gp91phox and p47phox [204][105]. It was demonstrated that diabetic rat atrial myocytes had significantly reduced L-type Ca2+ current, but increased T-type which was reversed by rosuvastatin [205][106]. This statin attenuated or reversed SERCA2a, phosphorylated Cx43 and phospholamban down-regulation in the ischemia/reperfusion. Rosuvastatin also accelerated Cai decay and ameliorated conduction inhomogeneity. These are abnormal in injured myocardium. Statins also reduced the ryanodine receptor-2 (RyR2) cardiac activity [206[107][108],207], and this suppressed cardiac arrhythmias. In addition, simvastin acetylcholine activated K+ current attenuation and shortened APD restoration in mouse atrial cardiomyocytes [208][109] could be one AF prevention mechanism.

Atorvastatin up-regulated the myocardial Cx43 protein and also activated the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase pathway and mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the ischemia-reperfusion rat model [194][95]. The myocardial Cx43 up-regulation was also demonstrated in the hereditary hyper-triglyceridemia rat strain [191][92]. These studies indicate that Cx43 preservation may be implicated in VF protection by statins.

Further statin reports included; (1) pravastatin decreased the incidence of post-myocardial infarction VT and Ca2+ alternans in mouse hearts. This was partly achieved by reversing Ca2+ handling abnormalities through the protein phosphatase pathway [209][110]; (2) simvastatin administered prior to ischaemia/reperfusion reduced VF incidence, and treatment preserved endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity and NO availability during occlusion, and attenuated superoxide production following reperfusion [210][111]; (3) PI3-kinase/Akt pathway activation was involved in acute simvastatin effects against ischemia/reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in anaesthetized dogs [211][112]; (4) atorvastatin also normalized the myocardial expression level of miRNA-1 known to be involved in Cx43 regulation in rats exposed to irradiation [212][113]; (5) atorvasatin inhibited the transient Na+ current (INa) abnormally increased in rat cardiomyocyets in early ischaemia or reperfusion [213,214][114][115] and (6) endothelial Klf2-TGFβ1 or Klf2-Foxp1-TGFβ1 pathway-mediated preventive effects of simvastin against pressure overload induced maladaptive cardiac remodeling [215][116].

The suppressive effect of rosuvastatin on atrial tachypacing-induced cellular remodeling was mediated by the activation of Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. This is a possible explanation for the statin AF protective effect [216][117]. It is also noteworthy that heme oxygenase-1 is a potent antioxidant factor, and the suppression of atrial myeloperoxidase and MMP-2, MMP-9 may contribute to the prevention of atorvastatin in atrial remodeling in the rabbit model of rapid pacing-induced AF [217][118].

Available findings suggest that attenuation of inflammation and oxidative stress as well as modulation of ion channels, Ca2+ handling, Cx43 and specific signalling pathways may be implicated in antiarrhythmic effects of statins (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Molecular mechanism of statins underlying their antiarrhythmic properties. See references [42,152,161,194,201,204,206,216][61][50][60][95][102][105][107][117].

Conclusions

3. Conclusions

Evidence suggest that potent anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative compounds impact pro-arrhythmic factors and the development of arrhythmia substrate. Further research should explore as whether SGLT2 inhibitors and statins as well as other cardio-protective compounds are able to control the NLRP

inflammasome signaling via inhibition of Cx-hemichannels and pannexin-1 channels. It may be a paradigm for the development of novel drugs aimed to prevent occurrence of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and deleterious atrial arrhythmias.

inflammasome signaling via inhibition of Cx-hemichannels and pannexin-1 channels. It may be a paradigm for the development of novel drugs aimed to prevent occurrence of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and deleterious atrial arrhythmias.

References

- Cosentino, F.; Grant, P.J.; Aboyans, V.; Bailey, C.J.; Ceriello, A.; Delgado, V.; Federici, M.; Filippatos, G.; Grobbee, D.E.; Hansen, T.B.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 255–323.

- Costard-Jäckle, A.; Tschöpe, D.; Meinertz, T. Cardiovascular outcome in type 2 diabetes and atrial fibrillation. Herz 2019, 44, 522–525.

- Chan, Y.H.; Chen, S.W.; Chao, T.F.; Kao, Y.W.; Huang, C.Y.; Chu, P.H. The impact of weight loss related to risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 93.

- Masson, W.; Lavalle-Cobo, A.; Nogueira, J.P. Effect of sglt2-inhibitors on epicardial adipose tissue: A meta-analysis. Cells 2021, 10, 2150.

- Scott, L.; Fender, A.C.; Saljic, A.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Linz, D.; Lang, J.; Hohl, M.; Twomey, D.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasome is a key driver of obesity-induced atrial arrhythmias. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 1746–1759.

- Patel, K.H.K.; Hwang, T.; Se Liebers, C.; Ng, F.S. Epicardial adipose tissue as a mediator of cardiac arrhythmias. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2021, 322, 129–144.

- Soucek, F.; Covassin, N.; Singh, P.; Ruzek, L.; Kara, T.; Suleiman, M.; Lerman, A.; Koestler, C.; Friedman, P.A.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; et al. Effects of Atorvastatin (80 mg) Therapy on Quantity of Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Patients Undergoing Pulmonary Vein Isolation for Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 116, 1443–1446.

- Lee, T.W.; Lee, T.I.; Lin, Y.K.; Chen, Y.C.; Kao, Y.H.; Chen, Y.J. Effect of antidiabetic drugs on the risk of atrial fibrillation: Mechanistic insights from clinical evidence and translational studies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 923–934.

- Böhm, M.; Slawik, J.; Brueckmann, M.; Mattheus, M.; George, J.T.; Ofstad, A.P.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Fitchett, D.; Anker, S.D.; Marx, N.; et al. Efficacy of empagliflozin on heart failure and renal outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: Data from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 126–135.

- Ling, A.W.C.; Chan, C.C.; Chen, S.W.; Kao, Y.W.; Huang, C.Y.; Chan, Y.H.; Chu, P.H. The risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors versus dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 188.

- Bonora, B.M.; Raschi, E.; Avogaro, A.; Fadini, G.P. SGLT-2 inhibitors and atrial fibrillation in the Food and Drug Administration adverse event reporting system. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 39.

- Li, W.J.; Chen, X.Q.; Xu, L.L.; Li, Y.Q.; Luo, B.H. SGLT2 inhibitors and atrial fibrillation in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 130.

- Okunrintemi, V.; Mishriky, B.M.; Powell, J.R.; Cummings, D.M. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors and atrial fibrillation in the cardiovascular and renal outcome trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021, 23, 276–280.

- Tanaka, H.; Tatsumi, K.; Matsuzoe, H.; Soga, F.; Matsumoto, K.; Hirata, K. ichi Association of type 2 diabetes mellitus with the development of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: Impact of SGLT2 inhibitors. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 37, 1333–1341.

- Fitchett, D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Cannon, C.P.; McGuire, D.K.; Scirica, B.M.; Johansen, O.E.; Sambevski, S.; Kaspers, S.; Pfarr, E.; George, J.T.; et al. Empagliflozin Reduced Mortality and Hospitalization for Heart Failure across the Spectrum of Cardiovascular Risk in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME Trial. Circulation 2019, 139, 1384–1395.

- Zelniker, T.A.; Bonaca, M.P.; Furtado, R.H.M.; Mosenzon, O.; Kuder, J.F.; Murphy, S.A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Leiter, L.A.; McGuire, D.K.; Wilding, J.P.H.; et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on atrial fibrillation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Insights from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 Trial. Circulation 2020, 141, 1227–1234.

- Li, H.L.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Feng, Q.; Fei, Y.; Tse, Y.K.; Wu, M.Z.; Ren, Q.W.; Tse, H.F.; Cheung, B.M.Y.; Yiu, K.H. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and cardiac arrhythmias: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 100.

- Zhou, L.; Yang, Y.; Han, W. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors protect against atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 10887–10895.

- Curtain, J.P.; Docherty, K.F.; Jhund, P.S.; Petrie, M.C.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kober, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on ventricular arrhythmias, resuscitated cardiac arrest, or sudden death in DAPA-HF. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3727–3738.

- Sfairopoulos, D.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Letsas, K.P.; Tse, G.; Li, G.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Liu, T.; Korantzopoulos, P. Association between sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and risk of sudden cardiac death or ventricular arrhythmias: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. EP Eur. 2022, 24, 20–30.

- Ilyas, F.; Jones, L.; Tee, S.L.; Horsfall, M.; Swan, A.; Wollaston, F.; Hecker, T.; De Pasquale, C.; Thomas, S.; Chong, W.; et al. Acute pleiotropic effects of dapagliflozin in type 2 diabetic patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A crossover trial. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 4346–4352.

- Light, P.E. Decoding the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on cardiac arrhythmias in heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3739–3740.

- Teo, Y.H.; Teo, Y.N.; Syn, N.L.; Kow, C.S.; Yoong, C.S.Y.; Tan, B.Y.Q.; Yeo, T.C.; Lee, C.H.; Lin, W.; Sia, C.H. Effects of sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 (Sglt2) inhibitors on cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes in patients without diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e019463.

- Yu, Y.W.; Zhao, X.M.; Wang, Y.H.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhai, M.; Zhang, J. Effect of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on cardiac structure and function in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with or without chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 25.

- Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Tse, G.; Korantzopoulos, P.; Letsas, K.P.; Zhang, Q.; Li, G.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Liu, T. Effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors on cardiac remodelling: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, zwab173.

- Zhang, D.P.; Xu, L.; Wang, L.F.; Wang, H.J.; Jiang, F. Effects of antidiabetic drugs on left ventricular function/dysfunction: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 10.

- Lopaschuk, G.D.; Verma, S. Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Benefits of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors: A State-of-the-Art Review. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2020, 5, 632–644.

- Ring, A.; Brand, T.; Macha, S.; Breithaupt-Groegler, K.; Simons, G.; Walter, B.; Woerle, H.J.; Broedl, U.C. The sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin does not prolong QT interval in a thorough QT (TQT) study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2013, 12, 70.

- Bode, D.; Semmler, L.; Oeing, C.U.; Alogna, A.; Schiattarella, G.G.; Pieske, B.M.; Heinzel, F.R.; Hohendanner, F. Implications of sglt inhibition on redox signalling in atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5937.

- Li, X.; Römer, G.; Kerindongo, R.P.; Hermanides, J.; Albrecht, M.; Hollmann, M.W.; Zuurbier, C.J.; Preckel, B.; Weber, N.C. Sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors ameliorate endothelium barrier dysfunction induced by cyclic stretch through inhibition of reactive oxygen species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6044.

- Koyani, C.N.; Plastira, I.; Sourij, H.; Hallström, S.; Schmidt, A.; Rainer, P.P.; Bugger, H.; Frank, S.; Malle, E.; von Lewinski, D. Empagliflozin protects heart from inflammation and energy depletion via AMPK activation. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 158, 104870.

- Prattichizzo, F.; De Nigris, V.; Micheloni, S.; La Sala, L.; Ceriello, A. Increases in circulating levels of ketone bodies and cardiovascular protection with SGLT2 inhibitors: Is low-grade inflammation the neglected component? Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 2515–2522.

- Sardu, C.; Massetti, M.; Testa, N.; Di Martino, L.; Castellano, G.; Turriziani, F.; Sasso, F.C.; Torella, M.; De Feo, M.; Santulli, G.; et al. Effects of Sodium-Glucose Transporter 2 Inhibitors (SGLT2-I) in Patients With Ischemic Heart Disease (IHD) Treated by Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting via MiECC: Inflammatory Burden, and Clinical Outcomes at 5 Years of Follow-Up. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 777083.

- Azam, M.A.; Chakraborty, P.; Si, D.; Du, B.B.; Massé, S.; Lai, P.F.H.; Ha, A.C.T.; Nanthakumar, K. Anti-arrhythmic and inotropic effects of empagliflozin following myocardial ischemia. Life Sci. 2021, 276, 119440.

- Jespersen, N.; Lassen, T.; Hjortbak, M.; Stottrup, N.; Botker, H. Sodium Glucose Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibition does not Protect the Myocardium from Acute Ischemic Reperfusion Injury but Modulates Post- Ischemic Mitochondrial Function. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Open Access 2017, 6, 2–4.

- Hu, Z.; Ju, F.; Du, L.; Abbott, G.W. Empagliflozin protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion-induced sudden cardiac death. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 199.

- Lee, C.C.; Chen, W.T.; Chen, S.Y.; Lee, T.M. Dapagliflozin attenuates arrhythmic vulnerabilities by regulating connexin43 expression via the AMPK pathway in post-infarcted rat hearts. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 192, 114674.

- Kondo, H.; Akoumianakis, I.; Badi, I.; Akawi, N.; Kotanidis, C.P.; Polkinghorne, M.; Stadiotti, I.; Sommariva, E.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Carena, M.C.; et al. Effects of canagliflozin on human myocardial redox signalling: Clinical implications. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4947–4960.

- Heller, S.; Darpö, B.; Mitchell, M.I.; Linnebjerg, H.; Leishman, D.J.; Mehrotra, N.; Zhu, H.; Koerner, J.; Fiszman, M.L.; Balakrishnan, S.; et al. Considerations for assessing the potential effects of antidiabetes drugs on cardiac ventricular repolarization: A report from the Cardiac Safety Research Consortium. Am. Heart J. 2015, 170, 23–35.

- Durak, A.; Olgar, Y.; Degirmenci, S.; Akkus, E.; Tuncay, E.; Turan, B. A SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin suppresses prolonged ventricular-repolarization through augmentation of mitochondrial function in insulin-resistant metabolic syndrome rats. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 144.

- Lahnwong, S.; Palee, S.; Apaijai, N.; Sriwichaiin, S.; Kerdphoo, S.; Jaiwongkam, T.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Chattipakorn, N. Acute dapagliflozin administration exerts cardioprotective effects in rats with cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 91.

- Lin, Y.W.; Chen, C.Y.; Shih, J.Y.; Cheng, B.C.; Chang, C.P.; Lin, M.T.; Ho, C.H.; Chen, Z.C.; Fisch, S.; Chang, W.T. Dapagliflozin improves cardiac hemodynamics and mitigates arrhythmogenesis in mitral regurgitation-induced myocardial dysfunction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e019274.

- Bariş, V.Ö.; Dinçsoy, B.; Gedikli, E.; Erdem, A. Empagliflozin significantly attenuates sotalol-induced QTc prolongation in rats. Kardiol. Pol. 2021, 79, 53–57.

- Baartscheer, A.; Schumacher, C.A.; Wüst, R.C.I.; Fiolet, J.W.T.; Stienen, G.J.M.; Coronel, R.; Zuurbier, C.J. Empagliflozin decreases myocardial cytoplasmic Na+ through inhibition of the cardiac Na+/H+ exchanger in rats and rabbits. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 568–573.

- Lee, T.I.; Chen, Y.C.; Lin, Y.K.; Chung, C.C.; Lu, Y.Y.; Kao, Y.H.; Chen, Y.J. Empagliflozin attenuates myocardial sodium and calcium dysregulation and reverses cardiac remodeling in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1680.

- Zuurbier, C.J.; Baartscheer, A.; Schumacher, C.A.; Fiolet, J.W.T.; Coronel, R. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin inhibits the cardiac Na+/H+ exchanger 1: Persistent inhibition under various experimental conditions. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 2699–2701.

- Trum, M.; Riechel, J.; Wagner, S. Cardioprotection by sglt2 inhibitors—does it all come down to Na+ ? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7976.

- Jhuo, S.J.; Liu, I.H.; Tasi, W.C.; Chou, T.W.; Lin, Y.H.; Wu, B.N.; Lee, K.T.; Lai, W. Ter Characteristics of ventricular electrophysiological substrates in metabolic mice treated with empagliflozin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6105.

- Bode, D.; Semmler, L.; Wakula, P.; Hegemann, N.; Primessnig, U.; Beindorff, N.; Powell, D.; Dahmen, R.; Ruetten, H.; Oeing, C.; et al. Dual SGLT-1 and SGLT-2 inhibition improves left atrial dysfunction in HFpEF. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 7.

- Mustroph, J.; Wagemann, O.; Lücht, C.M.; Trum, M.; Hammer, K.P.; Sag, C.M.; Lebek, S.; Tarnowski, D.; Reinders, J.; Perbellini, F.; et al. Empagliflozin reduces ca/calmodulin-dependent kinase ii activity in isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes. ESC Heart Fail. 2018, 5, 642–648.

- Nishinarita, R.; Niwano, S.; Niwano, H.; Nakamura, H.; Saito, D.; Sato, T.; Matsuura, G.; Arakawa, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Shirakawa, Y.; et al. Canagliflozin suppresses atrial remodeling in a canine atrial fibrillation model. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e017483.

- Shao, Q.; Meng, L.; Lee, S.; Tse, G.; Gong, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, T. Empagliflozin, a sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor, alleviates atrial remodeling and improves mitochondrial function in high-fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 165.

- Song, Y.; Huang, C.; Sin, J.; Germano, J.D.F.; Taylor, D.J.R.; Thakur, R.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Mentzer, R.M.; Andres, A.M. Attenuation of Adverse Postinfarction Left Ventricular Remodeling with Empagliflozin Enhances Mitochondria-Linked Cellular Energetics and Mitochondrial Biogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 437.

- Beri, A.; Contractor, T.; Khasnis, A.; Thakur, R. Statins and the reduction of sudden cardiac death: Antiarrhythmic or anti-ischemic effect? Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2010, 10, 155–164.

- Ghaisas, M.M.; Dandawate, P.R.; Zawar, S.A.; Ahire, Y.S.; Gandhi, S.P. Antioxidant, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin in various experimental models. Inflammopharmacology 2010, 18, 169–177.

- Niessner, A.; Steiner, S.; Speidl, W.S.; Pleiner, J.; Seidinger, D.; Maurer, G.; Goronzy, J.J.; Weyand, C.M.; Kopp, C.W.; Huber, K.; et al. Simvastatin suppresses endotoxin-induced upregulation of toll-like receptors 4 and 2 in vivo. Atherosclerosis 2006, 189, 408–413.

- Ascer, E.; Bertolami, M.C.; Venturinelli, M.L.; Buccheri, V.; Souza, J.; Nicolau, J.C.; Ramires, J.A.F.; Serrano, C.V. Atorvastatin reduces proinflammatory markers in hypercholesterolemic patients. Atherosclerosis 2004, 177, 161–166.

- Satoh, M.; Tabuchi, T.; Itoh, T.; Nakamura, M. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in coronary artery disease: Results from prospective and randomized study of treatment with atorvastatin or rosuvastatin. Clin. Sci. 2014, 126, 233–241.

- Lu, T.; Yang, X.; Cai, Y.; Xie, C.; Zhang, B. Prestroke statins improve prognosis of atrial fibrillation-associated stroke through increasing suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 levels. Eur. Neurol. 2021, 84, 96–102.

- Vieira-Silva, S.; Falony, G.; Belda, E.; Nielsen, T.; Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Chakaroun, R.; Forslund, S.K.; Assmann, K.; Valles-Colomer, M.; Nguyen, T.T.D.; et al. Statin therapy is associated with lower prevalence of gut microbiota dysbiosis. Nature 2020, 581, 310–315.

- Linz, D.; Gawałko, M.; Sanders, P.; Penders, J.; Li, N.; Nattel, S.; Dobrev, D. Does gut microbiota affect atrial rhythm? Causalities and speculations. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3521–3525.

- Buber, J.; Goldenberg, I.; Moss, A.J.; Wang, P.J.; McNitt, S.; Hall, W.J.; Eldar, M.; Barsheshet, A.; Shechter, M. Reduction in life-threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias in statin-treated patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy enrolled in the MADIT-CRT (Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial with Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 749–755.

- Liao, Y.C.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Hung, C.Y.; Huang, J.L.; Lin, C.H.; Wang, K.Y.; Wu, T.J. Statin therapy reduces the risk of ventricular arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death, and mortality in heart failure patients: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 4805–4807.

- Rusnak, J.; Behnes, M.; Schupp, T.; Lang, S.; Reiser, L.; Taton, G.; Bollow, A.; Reichelt, T.; Ellguth, D.; Engelke, N.; et al. Statin therapy is associated with improved survival in patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Lipids Health Dis. 2019, 18, 119.

- Rahimi, K.; Majoni, W.; Merhi, A.; Emberson, J. Effect of statins on ventricular tachyarrhythmia, cardiac arrest, and sudden cardiac death: A meta-analysis of published and unpublished evidence from randomized trials. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1571–1581.

- Wanahita, N.; Chen, J.; Bangalore, S.; Shah, K.; Rachko, M.; Coleman, C.I.; Schweitzer, P. The effect of statin therapy on ventricular tachyarrhythmias: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Ther. 2012, 19, 16–23.

- Jacob, S.; Manickam, P.; Rathod, A.; Badheka, A.; Afonso, L.; Aravindhakshan, R. Statin therapy significantly reduces risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Am. J. Ther. 2012, 19, 261–268.

- Abuissa, H.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Bybee, K.A. Statins as antiarrhythmics: A systematic review part II: Effects on risk of ventricular arrhythmias. Clin. Cardiol. 2009, 32, 549–552.

- Liu, Y.-B.; Lee, Y.-T.; Pak, H.-N.; Lin, S.-F.; Fishbein, M.C.; Chen, L.S.; Merz, C.N.B.; Chen, P.-S. Effects of simvastatin on cardiac neural and electrophysiologic remodeling in rabbits with hypercholesterolemia. Heart Rhythm 2009, 6, 69–75.

- Park, J.S.; Kim, B.W.; Hong, T.J.; Choe, J.C.; Lee, H.W.; Oh, J.H.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, H.C.; Cha, K.S.; Jeong, M.H. Lower In-Hospital Ventricular Tachyarrhythmia in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Receiving Prior Statin Therapy. Angiology 2018, 69, 892–899.

- Chen, M.J.; Bala, A.; Huddleston, J.I.; Goodman, S.B.; Maloney, W.J.; Aaronson, A.J.; Amanatullah, D.F. Statin use is associated with less postoperative cardiac arrhythmia after total hip arthroplasty. HIP Int. 2019, 29, 618–623.

- Bonano, J.C.; Aratani, A.K.; Sambare, T.D.; Goodman, S.B.; Huddleston, J.I.; Maloney, W.J.; Burk, D.R.; Aaronson, A.J.; Finlay, A.K.; Amanatullah, D.F. Perioperative Statin Use May Reduce Postoperative Arrhythmia Rates After Total Joint Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 3401–3405.

- Chen, W.R.; Liu, H.B.; Sha, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wang, H.; Yin, D.W.; Chen, Y.D.; Shi, X.M. Effects of statin on arrhythmia and heart rate variability in healthy persons with 48-hour sleep deprivation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003833.

- Bastani, M.; Khosravi, M.; Shafa, M.; Azemati, S.; Maghsoodi, B.; Asadpour, E. Evaluation of high-dose atorvastatin pretreatment influence in patients preconditioning of post coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A prospective triple blind randomized clinical trial. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2021, 24, 209–216.

- Zhen-Han, L.; Rui, S.; Dan, C.; Xiao-Li, Z.; Qing-Chen, W.; Bo, F. Perioperative statin administration with decreased risk of postoperative atrial fibrillation, but not acute kidney injury or myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10091.

- Sun, Y.; Ji, Q.; Mei, Y.; Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Cai, J.; Chi, L. Role of preoperative atorvastatin administration in protection against postoperative atrial fibrillation following conventional coronary artery bypass grafting. Int. Heart J. 2011, 52, 7–11.

- Nomani, H.; Mohammadpour, A.H.; Reiner, Ž.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Statin therapy in post-operative atrial fibrillation: Focus on the anti-inflammatory effects. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2021, 8, 24.

- Jayaram, R.; Jones, M.; Reilly, S.; Crabtree, M.J.; Pal, N.; Goodfellow, N.; Nahar, K.; Simon, J.; Carnicer, R.; DeSilva, R.; et al. Atrial nitroso-redox balance and refractoriness following on-pump cardiac surgery: A randomized trial of atorvastatin. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 184–195.

- Reilly, S.N.; Jayaram, R.; Nahar, K.; Antoniades, C.; Verheule, S.; Channon, K.M.; Alp, N.J.; Schotten, U.; Casadei, B. Atrial sources of reactive oxygen species vary with the duration and substrate of atrial fibrillation: Implications for the antiarrhythmic effect of statins. Circulation 2011, 124, 1107–1117.

- Acampa, M.; Lazzerini, P.E.; Guideri, F.; Tassi, R.; Lo Monaco, A.; Martini, G. Previous use of Statins and Atrial Electrical Remodeling in Patients with Cryptogenic Stroke. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Disord. Targets 2018, 17, 212–215.

- Hou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zheng, S.; Hou, Y.; Gao, M. Effects of rosuvastatin on atrial nerve sprouting and electrical remodeling in rabbits with myocardial infarction. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 7553–7560.

- Peng, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, H. The effect of statins on the recurrence rate of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation: A meta-analysis. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2018, 41, 1420–1427.

- Jia, Q.; Han, W.; Shi, S.; Hu, Y. The effects of ACEI/ARB, aldosterone receptor antagonists and statins on preventing recurrence of atrial fibrillation: A protocol for systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e24280.

- Santangeli, P.; Ferrante, G.; Pelargonio, G.; Dello Russo, A.; Casella, M.; Bartoletti, S.; Di Biase, L.; Crea, F.; Natale, A. Usefulness of statins in preventing atrial fibrillation in patients with permanent pacemaker: A systematic review. Europace 2010, 12, 649–654.

- Soliman, E.Z.; Howard, G.; Judd, S.; Bhave, P.D.; Howard, V.J.; Herrington, D.M. Factors Modifying the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation Associated With Atrial Premature Complexes in Patients with Hypertension. Am. J. Cardiol. 2020, 125, 1324–1331.

- Tseng, C.H.; Chung, W.J.; Li, C.Y.; Tsai, T.H.; Lee, C.H.; Hsueh, S.K.; Wu, C.C.; Cheng, C.I. Statins reduce new-onset atrial fibrillation after acute myocardial infarction: A nationwide study. Medicine 2020, 99, e18517.

- Tekin, A.; Tekin, G.; Sezgin, A.T.; Müderrisoğlu, H. Short- and long-term effect of simvastatin therapy on the heterogeneity of cardiac repolarization in diabetic patients. Pharmacol. Res. 2008, 57, 393–397.

- Munhoz, D.B.; Carvalho, L.S.F.; Venancio, F.N.C.; Rangel de Almeida, O.L.; Quinaglia e Silva, J.C.; Coelho-Filho, O.R.; Nadruz, W.; Sposito, A.C. Statin Use in the Early Phase of ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Is Associated with Decreased QTc Dispersion. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 25, 226–231.

- Mitchell, L.B.; Powell, J.L.; Gillis, A.M.; Kehl, V.; Hallstrom, A.P. Are lipid-lowering drugs also antiarrhythmic drugs? An analysis of the Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 42, 81–87.

- Mohammed, K.S.; Kowey, P.R.; Musco, S. Adjuvant therapy for atrial fibrillation. Future Cardiol. 2010, 6, 67–81.

- Okumus, T.; Pala, A.A.; Taner, T.; Aydin, U. Effects of preoperative statin on the frequency of ventricular fibrillation and c-reactive protein level in patients undergoing isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2021, 31, 373–378.

- Bacova, B.; Radosinska, J.; Knezl, V.; Kolenova, L.; Weismann, P.; Navarova, J.; Barancik, M.; Mitasikova, M.; Tribulova, N. Omega-3 fatty acids and atorvastatin suppress ventricular fibrillation inducibility in hypertriglyceridemic rat hearts: Implication of intercellular coupling protein, connexin-43. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010, 61, 717–723.

- Benova, T.; Knezl, V.; Viczenczova, C.; Bacova, B.S.; Radosinska, J.; Tribulova, N. Acute anti-fibrillating and defibrillating potential of atorvastatin, melatonin, eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid demonstrated in isolated heart model. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 66, 83–89.

- Chou, C.-C.; Lee, H.-L.; Huang, Y.-C.; Wo, H.-T.; Wen, M.-S.; Chu, Y.; Chang, P.-C. Single Bolus Rosuvastatin Accelerates Calcium Uptake and Attenuates Conduction Inhomogeneity in Failing Rabbit Hearts With Regional Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 75, 64–74.

- Bian, B.; Yu, X.; Wang, Q.; Teng, T.; Nie, J. Atorvastatin protects myocardium against ischemia–reperfusion arrhythmia by increasing Connexin 43 expression: A rat model. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 768, 13–20.

- Liptak, B.; Knezl, V.; Gasparova, Z. Anti-arrhythmic and cardio-protective effects of atorvastatin and a potent pyridoindole derivative on isolated hearts from rats with metabolic syndrome. Bratisl. Med. J. 2019, 120, 200–206.

- Yang, N.; Cheng, W.; Hu, H.; Xue, M.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Xuan, Y.; Li, X.; Yin, J.; Shi, Y.; et al. Atorvastatin attenuates sympathetic hyperinnervation together with the augmentation of M2 macrophages in rats postmyocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2016, 34, 234–244.

- Najjari, M.; Vaezi, G.; Hojati, V.; Mousavi, Z.; Bakhtiarian, A.; Nikoui, V. Involvement of IL-1β and IL-6 in antiarrhythmic properties of atorvastatin in ouabain-induced arrhythmia in rats. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2018, 40, 256–261.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Shan, Z.L.; Guo, H.Y.; Guan, Y.; Yuan, H.T. Role of inflammation in the initiation and maintenance of atrial fibrillation and the protective effect of atorvastatin in a goat model of aseptic pericarditis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 2615–2623.

- Maguy, A.; Hebert, T.E.; Nattel, S. Involvement of lipid rafts and caveolae in cardiac ion channel function. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 69, 798–807.

- Balycheva, M.; Faggian, G.; Glukhov, A.V.; Gorelik, J. Microdomain–specific localization of functional ion channels in cardiomyocytes: An emerging concept of local regulation and remodelling. Biophys. Rev. 2015, 7, 43–62.

- Redondo-Morata, L.; Lea Sanford, R.; Andersen, O.S.; Scheuring, S. Effect of Statins on the Nanomechanical Properties of Supported Lipid Bilayers. Biophys. J. 2016, 111, 363–372.

- Ding, C.; Fu, X.H.; He, Z.S.; Chen, H.X.; Xue, L.; Li, J.X. Cardioprotective effects of simvastatin on reversing electrical remodeling induced by myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in normocholesterolemic rabbits. Chin. Med. J. 2008, 121, 551–556.

- Oesterle, A.; Liao, J.K. The Pleiotropic Effects of Statins—From Coronary Artery Disease and Stroke to Atrial Fibrillation and Ventricular Tachyarrhythmia. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2018, 17, 222–232.

- Ma, Y.; Kong, L.; Qi, S.; Wang, D. Atorvastatin blocks increased l-type Ca2+ current and cell injury elicited by angiotensin II via inhibiting oxide stress. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2016, 48, 378–384.

- Pan, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Rosuvastatin Alleviates Type 2 Diabetic Atrial Structural and Calcium Channel Remodeling. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2016, 67, 57–67.

- Venturi, E.; Lindsay, C.; Lotteau, S.; Yang, Z.; Steer, E.; Witschas, K.; Wilson, A.D.; Wickens, J.R.; Russell, A.J.; Steele, D.; et al. Simvastatin activates single skeletal RyR1 channels but exerts more complex regulation of the cardiac RyR2 isoform. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 938–952.

- Haseeb, M.; Thompson, P.D. The effect of statins on RyR and RyR-associated disease. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 131, 661–671.

- Cho, K.I.; Cha, T.J.; Lee, S.J.; Shim, I.K.; Zhang, Y.H.; Heo, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, K.L.; Lee, J.W. Attenuation of acetylcholine activated potassium current (IKACh) by simvastatin, not pravastatin in mouse atrial cardiomyocyte: Possible atrial fibrillation preventing effects of statin. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106570.

- Jin, H.; Welzig, C.M.; Aronovitz, M.; Noubary, F.; Blanton, R.; Wang, B.; Rajab, M.; Albano, A.; Link, M.S.; Noujaim, S.F.; et al. QRS/T-wave and calcium alternans in a type I diabetic mouse model for spontaneous postmyocardial infarction ventricular tachycardia: A mechanism for the antiarrhythmic effect of statins. Heart Rhythm 2017, 14, 1406–1416.

- Kisvári, G.; Kovács, M.; Gardi, J.; Seprényi, G.; Kaszaki, J.; Végh, Á. The effect of acute simvastatin administration on the severity of arrhythmias resulting from ischaemia and reperfusion in the canine: Is there a role for nitric oxide? Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 732, 96–104.

- Kisvári, G.; Kovács, M.; Seprényi, G.; Végh, Á. The activation of PI 3-kinase/Akt pathway is involved in the acute effects of simvastatin against ischaemia and reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in anaesthetised dogs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 769, 185–194.

- Kura, B.; Kalocayova, B.; Bacova, B.S.; Fulop, M.; Sagatova, A.; Sykora, M.; Andelova, K.; Abuawad, Z.; Slezak, J. The effect of selected drugs on the mitigation of myocardial injury caused by gamma radiation. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 99, 80–88.

- Li, H.; Wan, Z.; Li, X.; Teng, T.; Du, X.; Nie, J. Effects of atorvastatin on time-dependent change of fast sodium current in simulated acute ischaemic ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2019, 30, 268–274.

- Nie, J.; Wang, G.; Zhao, G.; Du, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Q. Effects of Atorvastatin on Transient Sodium Currents in Rat Normal, Simulated Ischemia, and Reperfusion Ventricular Myocytes. Pharmacology 2020, 105, 320–328.

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Duan, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Zhuang, T.; Tomlinson, B.; et al. Endothelial Klf2-Foxp1-TGFβ signal mediates the inhibitory effects of simvastatin on maladaptive cardiac remodeling. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1609–1625.

- Yeh, Y.H.; Kuo, C.T.; Chang, G.J.; Chen, Y.H.; Lai, Y.J.; Cheng, M.L.; Chen, W.J. Rosuvastatin suppresses atrial tachycardia-induced cellular remodeling via Akt/Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 pathway. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 82, 84–92.

- Yang, Q.; Qi, X.; Dang, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, X.; Hao, X. Effects of atorvastatin on atrial remodeling in a rabbit model of atrial fibrillation produced by rapid atrial pacing. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2016, 16, 142.

More