The fusion of membranes is a central part of the physiological processes involving the intracellular transport and maturation of vesicles and the final release of their contents, such as neurotransmitters and hormones, by exocytosis. Traditionally lipids have been regarded as structural elements playing a relatively minor role in the molecular mechanisms of exocytosis whereas proteins such as SNAREs (soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor attachment protein receptors) are thought to be the central elements that generate the specificity and force needed for overcoming the repulsion of the negative charges within lipid bilayers that oppose fusion. The effect of sphingosine and synthetic derivatives on the heterologous and homologous fusion of organelles can be considered as a new mechanism of action of sphingolipids influencing important physiological processes, which could underlie therapeutic uses of sphingosine derived lipids in the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders and cancers of neuronal origin such neuroblastoma.

- sphingosine

- exocytosis

- vesicle fusion

- mitochondria

- neurotransmitter release

- neuroendocrine cells

1. Lipids and Exocytosis

2. The Direct Interaction between Sphingolipids and SNAREs

3. Sphingolipids Alter the Single Fusion Properties of Neurotransmitter Release

References

- Almers, W. Exocytosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1990, 52, 607–624.

- Betz, W.J.; Angleson, J.K. The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1998, 60, 347–363.

- Jahn, R.; Lang, T.; Sudhof, T.C. Membrane fusion. Cell 2003, 112, 519–533.

- Chanaday, N.L.; Cousin, M.A.; Milosevic, I.; Watanabe, S.; Morgan, J.R. The Synaptic Vesicle Cycle Revisited: New Insights into the Modes and Mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 8209–8216.

- Trifaro, J.M.; Gasman, S.; Gutierrez, L.M. Cytoskeletal control of vesicle transport and exocytosis in chromaffin cells. Acta Physiol. 2008, 192, 165–172.

- Gutierrez, L.M. New insights into the role of the cortical cytoskeleton in exocytosis from neuroendocrine cells. Int. Rev. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2012, 295, 109–137.

- James, D.J.; Martin, T.F. CAPS and Munc13: CATCHRs that SNARE Vesicles. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 187.

- Silva, M.; Tran, V.; Marty, A. Calcium-dependent docking of synaptic vesicles. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 579–592.

- Gundersen, C.B. Fast, synchronous neurotransmitter release: Past, present and future. Neuroscience 2020, 439, 22–27.

- Anantharam, A.; Kreutzberger, A.J.B. Unraveling the mechanisms of calcium-dependent secretion. J. Gen. Physiol. 2019, 151, 417–434.

- Bennett, M.K.; Scheller, R.H. Molecular correlates of synaptic vesicle docking and fusion. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1994, 4, 324–329.

- Burgoyne, R.D.; Morgan, A. Analysis of regulated exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells: Insights into NSF/SNAP/SNARE function. BioEssays 1998, 20, 328–335.

- Zhang, Y.; Hughson, F.M. Chaperoning SNARE Folding and Assembly. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2021, 90, 581–603.

- Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, H. Mechanism of membrane fusion: Protein-protein interaction and beyond. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2019, 11, 250–257.

- Pan, C.Y.; Wu, A.Z.; Chen, Y.T. Lysophospholipids regulate excitability and exocytosis in cultured bovine chromaffin cells. J Neurochem. 2007, 102, 944–956.

- Amatore, C.; Arbault, S.; Bouret, Y.; Guille, M.; Lemaitre, F.; Verchier, Y. Regulation of exocytosis in chromaffin cells by trans-insertion of lysophosphatidylcholine and arachidonic acid into the outer leaflet of the cell membrane. ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 1998–2003.

- Eberhard, D.A.; Cooper, C.L.; Low, M.G.; Holz, R.W. Evidence that the inositol phospholipids are necessary for exocytosis. Loss of inositol phospholipids and inhibition of secretion in permeabilized cells caused by a bacterial phospholipase C and removal of ATP. Biochem. J. 1990, 268, 15–25.

- Aoyagi, K.; Sugaya, T.; Umeda, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Terakawa, S.; Takahashi, M. The activation of exocytotic sites by the formation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate microdomains at syntaxin clusters. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 17346–17352.

- Eberhard, D.A.; Holz, R.W. Calcium promotes the accumulation of polyphosphoinositides in intact and permeabilized bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1991, 11, 357–370.

- Wen, P.J.; Osborne, S.L.; Zanin, M.; Low, P.C.; Wang, H.T.; Schoenwaelder, S.M.; Jackson, S.P.; Wedlich-Soldner, R.; Vanhaesebroeck, B.; Keating, D.J.; et al. Phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate coordinates actin-mediated mobilization and translocation of secretory vesicles to the plasma membrane of chromaffin cells. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 491.

- Lang, T.; Bruns, D.; Wenzel, D.; Riedel, D.; Holroyd, P.; Thiele, C.; Jahn, R. SNAREs are concentrated in cholesterol-dependent clusters that define docking and fusion sites for exocytosis. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 2202–2213.

- Hess, D.T.; Slater, T.M.; Wilson, M.C.; Skene, J.H. The 25 kDa synaptosomal-associated protein SNAP-25 is the major methionine-rich polypeptide in rapid axonal transport and a major substrate for palmitoylation in adult CNS. J. Neurosci. 1992, 12, 4634–4641.

- Veit, M.; Sollner, T.H.; Rothman, J.E. Multiple palmitoylation of synaptotagmin and the t-SNARE SNAP-25. FEBS Lett. 1996, 385, 119–123.

- Gonzalo, S.; Linder, M.E. SNAP-25 palmitoylation and plasma membrane targeting require a functional secretory pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998, 9, 585–597.

- Washbourne, P.; Cansino, V.; Mathews, J.R.; Graham, M.; Burgoyne, R.D.; Wilson, M.C. Cysteine residues of SNAP-25 are required for SNARE disassembly and exocytosis, but not for membrane targeting. Biochem. J. 2001, 357, 625–634.

- Baekkeskov, S.; Kanaani, J. Palmitoylation cycles and regulation of protein function (Review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 2009, 26, 42–54.

- Veit, M.; Becher, A.; Ahnert-Hilger, G. Synaptobrevin 2 is palmitoylated in synaptic vesicles prepared from adult, but not from embryonic brain. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2000, 15, 408–416.

- Rizo, J.; Chen, X.; Arac, D. Unraveling the mechanisms of synaptotagmin and SNARE function in neurotransmitter release. Trends Cell Biol. 2006, 16, 339–350.

- Chamberlain, L.H.; Burgoyne, R.D. Cysteine-string protein: The chaperone at the synapse. J. Neurochem. 2000, 74, 1781–1789.

- Evans, G.J.; Morgan, A.; Burgoyne, R.D. Tying everything together: The multiple roles of cysteine string protein (CSP) in regulated exocytosis. Traffic 2003, 4, 653–659.

- Graham, M.E.; Burgoyne, R.D. Comparison of cysteine string protein (Csp) and mutant alpha-SNAP overexpression reveals a role for csp in late steps of membrane fusion in dense-core granule exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 1281–1289.

- Balsinde, J.; Winstead, M.V.; Dennis, E.A. Phospholipase A(2) regulation of arachidonic acid mobilization. FEBS Lett. 2002, 531, 2–6.

- Winstead, M.V.; Balsinde, J.; Dennis, E.A. Calcium-independent phospholipase A(2): Structure and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1488, 28–39.

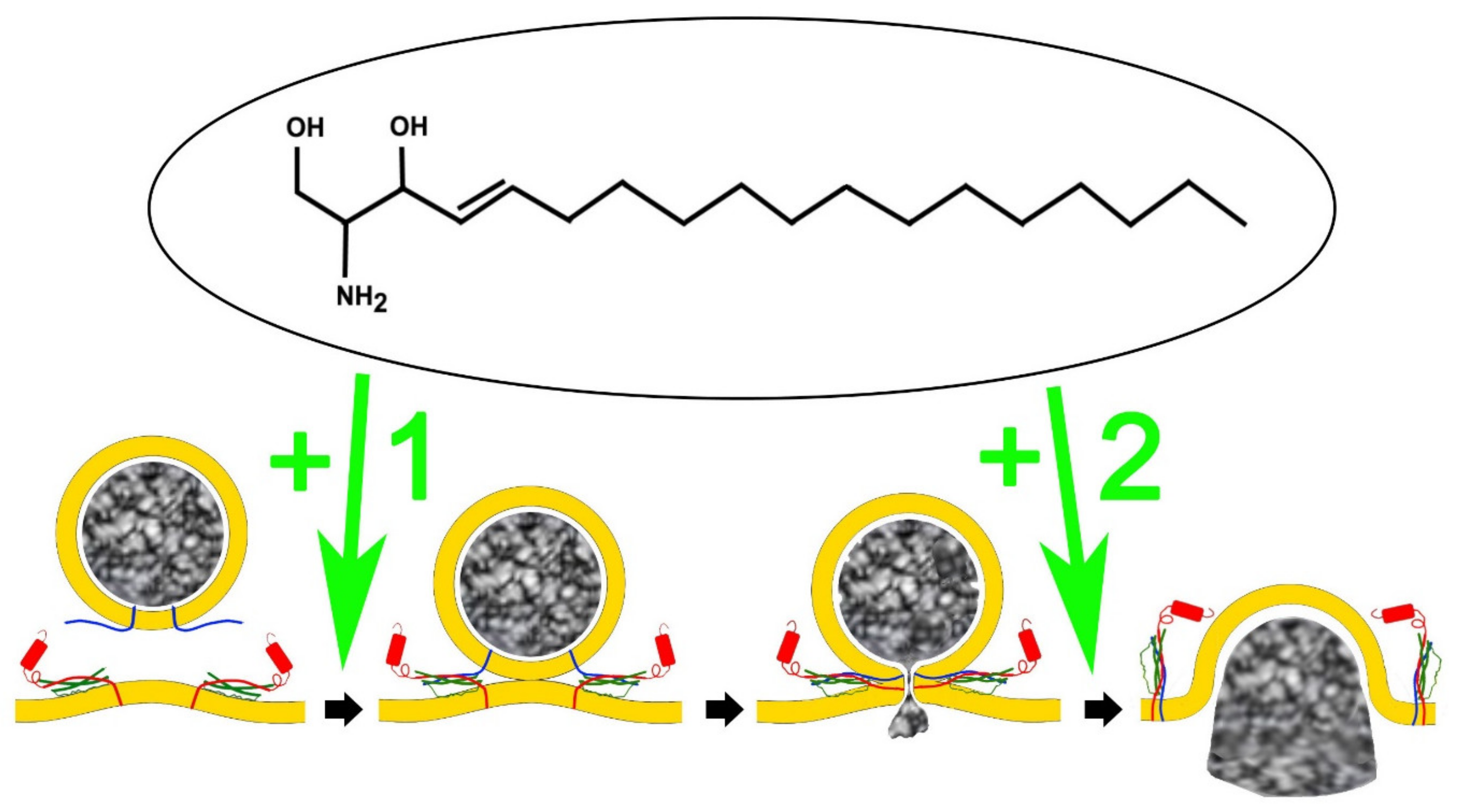

- Darios, F.; Wasser, C.; Shakirzyanova, A.; Giniatullin, A.; Goodman, K.; Munoz-Bravo, J.L.; Raingo, J.; Jorgacevski, J.; Kreft, M.; Zorec, R.; et al. Sphingosine facilitates SNARE complex assembly and activates synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Neuron 2009, 62, 683–694.

- Rickman, C.; Davletov, B. Arachidonic acid allows SNARE complex formation in the presence of Munc18. Chem. Biol. 2005, 12, 545–553.

- Connell, E.; Darios, F.; Broersen, K.; Gatsby, N.; Peak-Chew, S.Y.; Rickman, C.; Davletov, B. Mechanism of arachidonic acid action on syntaxin-Munc18. EMBO Rep. 2007, 8, 414–419.

- Darios, F.; Ruiperez, V.; Lopez, I.; Villanueva, J.; Gutierrez, L.M.; Davletov, B. Alpha- synuclein sequesters arachidonic acid to modulate SNARE-mediated exocytosis. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 528–533.

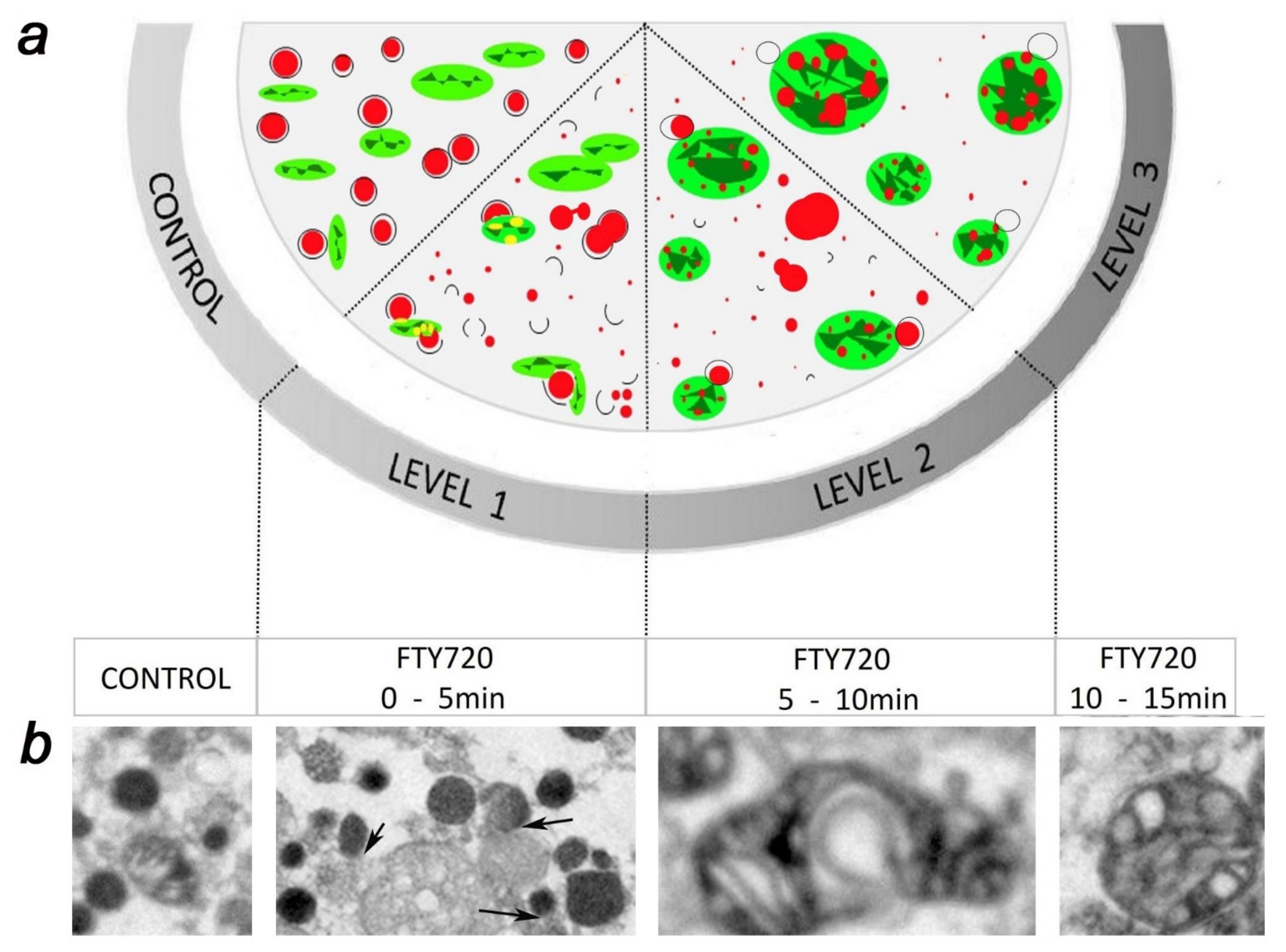

- Garcia-Martinez, V.; Villanueva, J.; Torregrosa-Hetland, C.J.; Bittman, R.; Higdon, A.; Darley- Usmar, V.M.; Davletov, B.; Gutierrez, L.M. Lipid metabolites enhance secretion acting on SNARE microdomains and altering the extent and kinetics of single release events in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75845.

- Garcia-Martinez, V.; Montes, M.A.; Villanueva, J.; Gimenez-Molina, Y.; de Toledo, G.A.; Gutierrez, L.M. Sphingomyelin derivatives increase the frequency of microvesicle and granule fusion in chromaffin cells. Neuroscience 2015, 295, 117–125.

- Camoletto, P.G.; Vara, H.; Morando, L.; Connell, E.; Marletto, F.P.; Giustetto, M.; Sassoe-Pognetto, M.; Van Veldhoven, P.P.; Ledesma, M.D. Synaptic vesicle docking: Sphingosine regulates syntaxin1 interaction with Munc18. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5310.

- Pan, C.Y.; Lee, H.; Chen, C.L. Lysophospholipids elevate i and trigger exocytosis in bovine chromaffin cells. Neuropharmacology 2006, 51, 18–26.

- Wu, A.Z.; Ohn, T.L.; Shei, R.J.; Wu, H.F.; Chen, Y.C.; Lee, H.C.; Dai, D.F.; Wu, S.N. Permissive Modulation of Sphingosine-1-Phosphate-Enhanced Intracellular Calcium on BKCa Channel of Chromaffin Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2175.

- Villanueva, J.; Torregrosa-Hetland, C.J.; García-Martínez, V.; Francés, M.M.; Viniegra, S.; Gutiérrez, L.M. The F-actin cortex in chromaffin granule dynamics and fusion: A minireview. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2012, 48, 323–327.

- Gutiérrez, L.M.; Villanueva, J. The role of F-actin in the transport and secretion of chromaffin granules: An historic perspective. Pflug. Arch. 2018, 470, 181–186.

- Becherer, U.; Rettig, J. Vesicle pools, docking, priming, and release. Cell Tissue Res. 2006, 326, 393–407.

- Zimmerberg, J.; Curran, M.; Cohen, F.S. A lipid/protein complex hypothesis for exocytotic fusion pore formation. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1991, 635, 307–317.

- Lindau, M.; de Toledo, G.A. The fusion pore. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2003, 1641, 167–173.

- Karatekin, E. Toward a unified picture of the exocytotic fusion pore. FEBS Lett. 2003, 592, 3563–3585.

- Lindau, M.; Neher, E. Patch-Clamp Techniques for Time-Resolved Capacitance Measurements in Single Cells. Pflug. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1988, 411, 137–146.

- Houy, S.; Martins, J.S.; Mohrmann, R.; Sørensen, J.B. Measurements of Exocytosis by Capacitance Recordings and Calcium Uncaging in Mouse Adrenal Chromaffin Cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2233, 233–251.

- Wightman, R.M.; Jankowski, J.A.; Kennedy, R.T.; Kawagoe, K.T.; Schroeder, T.J.; Leszczyszyn, D.J.; Near, J.A.; Diliberto, E.J., Jr.; Viveros, O.H. Temporally resolved catecholamine spikes correspond to single vesicle release from individual chromaffin cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 10754–10758.

- Álvarez de Toledo, G.; Montes, M.A.; Montenegro, P.; Borges, R. Phases of the exocytotic fusion pore. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 3532–3541.

- Flasker, A.; Jorgacevski, J.; Calejo, A.I.; Kreft, M.; Zorec, R. Vesicle size determines unitary exocytic properties and their sensitivity to sphingosine. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013, 376, 136–147.

- Jiang, Z.J.; Delaney, T.L.; Zanin, M.P.; Haberberger, R.V.; Pitson, S.M.; Huang, J.; Alford, S.; Cologna, S.M.; Keating, D.J.; Gong, L.W. Extracellular and intracellular sphingosine-1-phosphate distinctly regulates exocytosis in chromaffin cells. J. Neurochem. 2019, 149, 729–746.

- Abbineni, P.S.; Coorssen, J.R. Sphingolipids modulate docking, Ca2+ sensitivity and membrane fusion of native cortical vesicles. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 104, 43–54.

- Riganti, L.; Antonucci, F.; Gabrielli, M.; Prada, I.; Giussani, P.; Viani, P.; Valtorta, F.; Menna, E.; Matteoli, M.; Verderio, C. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P) Impacts Presynaptic Functions by Regulating Synapsin I Localization in the Presynaptic Compartment. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 4624–4634.

- Rosa, J.M.; Gandía, L.; García, A.G. Permissive role of sphingosine on calcium-dependent endocytosis in chromaffin cells. Pflug. Arch. 2010, 460, 901–914.