Ischemic stroke is a life-threatening cerebral vascular disease and accounts for high disability and mortality worldwide. Currently, no efficient therapeutic strategies are available for promoting neurological recovery in clinical practice, except rehabilitation. The majority of neuroprotective drugs showed positive impact in pre-clinical studies but failed in clinical trials. Therefore, there is an urgent demand for new promising therapeutic approaches for ischemic stroke treatment. Emerging evidence suggests that exosomes mediate communication between cells in both physiological and pathological conditions. Exosomes have received extensive attention for therapy following a stroke, because of their unique characteristics, such as the ability to cross the blood brain–barrier, low immunogenicity, and low toxicity. An increasing number of studies have demonstrated positively neurorestorative effects of exosome-based therapy, which are largely mediated by the microRNA cargo. Herein, we review the current knowledge of exosomes, the relationships between exosomes and stroke, and the therapeutic effects of exosome-based treatments in neurovascular remodeling processes after stroke. Exosomes provide a viable and prospective treatment strategy for ischemic stroke patients.

- exosome

- ischemic stroke

- microRNA

- neurorestoration

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics of Exosomes

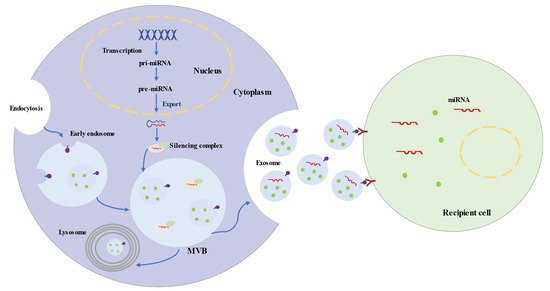

Exosomes represent a subspecies of extracellular vesicles (EVs) with structural size ranging from 30 to 150 nm, released from most cells in all living systems. They exist in various body fluids, such as cerebral spinal fluid, blood, saliva, and urine [26][27][28][29]. Exosomes are initiated by the invagination of the endosomal membrane (

3. Roles of Exosomes in Ischemic Stroke

3.1. Exosomes and Ischemic Stroke Diagnosis

In the central nervous system, exosomes derived from brain cells play significant roles in regulating normal physiological process and responding to acute brain injury [50]. Brain cells, including neurons, microglia, oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, endothelial cells, and pericytes, communicate with each other via their exosomes and exosomal cargos to regulate brain functions, from antioxidation to BBB integrity maintenance and synaptic function [51][52]. Following injury, exosomes are generated by brain cells and evoke diverse responses. Some exosomes seem to have beneficial effects in neuroprotection and neurological recovery. However, some exosomes also have adverse impacts involving neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation [53][54]. Moreover, these exosomes can pass through the BBB and circulate in the peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid and could be excellent noninvasive biomarkers for ischemic stroke diagnosis and prognosis [55][56]. Recent studies have detected many components in circulating exosomes which could serve as biomarkers for ischemic stroke, particularly, microRNAs (3.1. Exosomes and Ischemic Stroke Diagnosis

| microRNAs | Expression in IS | Sources | Models | Outcomes | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-9 | upregulation | serum | Human | NIHSS score, infarct volume, serum IL-6 |

[57] | [59] |

| miR-124 | upregulation | serum | Human | NIHSS score, infarct volume, serum IL-6 |

[57] |

| microRNAs | Models | Sources | Proposed Effects | Involved Pathway | References | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-133b | MCAO-rat | MSC | Neural remodeling | CTGF | |||||||||

| [ | 59 | ] | |||||||||||

| [ | 81 | ] | [ | 82 | ][83] | [86,87,88] | miR-223 | ||||||

| miR-17-92 cluster | MCAO-rat | MSC | Neural remodeling | PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathway | [85] | [90] | upregulation | serum | Human | NIHSS score, infarct volume, | |||

| miR-138-5p | 3-month mRS, stroke occurrence | MCAO-mouse OGD-astrocyte |

MSC | Anti-inflammation Anti-apoptosis | [58] | [60] | |||||||

| Lipocalin 2 | [ | 86 | ] | [ | 91] | miR-134 | upregulation | serum | Human | ||||

| 63 | |||||||||||||

| ] | |||||||||||||

| [ | |||||||||||||

| 65 | ] | ||||||||||||

| miR-30d-5p | MCAO-rat | NIHSS score, infarct volume, | serum IL-6, hs-CRP | OGD-microglia | MSC | Anti-inflammation Anti-apoptosis | [60] | [62] | |||||

| Beclin-1/Atg5 | [ | 87 | ] | [ | 92] | miR-422a | upregulation in acute phase downregulation in subacute phase |

plasma | Human | ||||

| miR-223-3p | MCAO-rat OGD-microglia |

MSC | different stages of IS | Anti-inflammation | [61] | CysLT2R-ERK1/2[63] | |||||||

| [ | 88 | ] | [ | 94 | ] | [93,99] | miR-125-2-3p | downregulation | plasma | Human | different stages of IS | [61] | [63] |

| miR-21-5p | upregulation in subacute phase upregulation in recovery phase |

plasma | Human | different stages of IS | [62] | [64] | |||||||

| miR-30a-5p | |||||||||||||

| miR-1906 | MCAO-mouse OGD-neuron |

MSC | Anti-inflammation | TLR4 | [89] | [94] | |||||||

| miR-132-3p | MCAO-mouse endothelial cell |

MSC | BBB protection Reduce vascular ROS |

PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway | [90] | [95] | upregulation in hyperacute phase downregulation in acute phase |

plasma | Human | different stages of IS | [62] | [64] | |

| miR-21-3p | MCAO-rat | MSC | BBB protection Anti-inflammation Anti-apoptosis |

MAT2B | [91] | [96] | miR-17-5p | upregulation | serum | Human | |||

| miR-134 | subtypes of stroke | OGD-oligodendrocyte | [ | 63 | ] | MSC[65] | |||||||

| Anti-apoptosis | Caspase-8 | [ | 92 | ] | [97] | miR-20b-5p | upregulation | serum | Human | ||||

| miR-184 | MCAO-rat | MSC | Neurogenesis | subtypes of stroke | Angiogenesis | ---- | [ | [93] | [98] | miR-27b-3p | upregulation | serum | Human |

| miR-210 | subtypes of stroke | MCAO-rat | [ | MSC | Neurogenesis Angiogenesis | 63 | ephrin-A3 | ] | [65] | ||||

| miR-93-5p | upregulation | serum | Human | subtypes of stroke | [63] | [65] | |||||||

| miR-15a | downregulation | serum | Human | subgroups of stroke | [64] | [66] | |||||||

| miR-100 | downregulation | serum | Human | subgroups of stroke | [64] | [66] | |||||||

| miR-339 | downregulation | serum | Human | subgroups of stroke | [64] | [66] | |||||||

| miR-424 | downregulation | serum | Human | subgroups of stroke | [64] | [66] | |||||||

| miR-122-5p | downregulation | plasma | Rat | different stages of IS | [65] | [67] | |||||||

| miR-300-3p | upregulation | plasma | Rat | different stages of IS | [65] | [67] | |||||||

| miR-126 | downregulation | serum | Rat | different stages of IS | [59] | [61] |

3.2. Exosomes and Ischemic Stroke Treatment

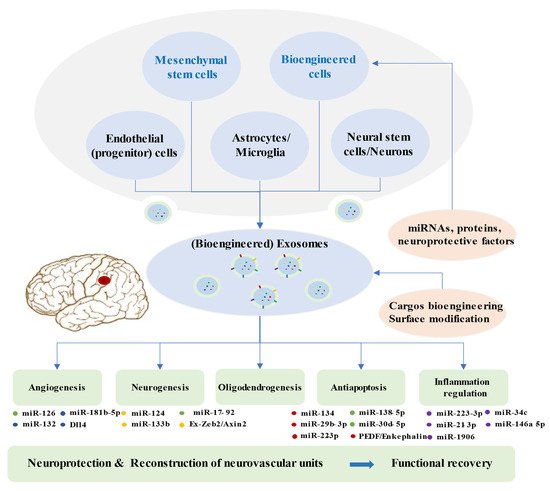

Multiple studies demonstrated that cell-based therapy is an excellent method to promote functional outcomes after ischemic stroke, especially if based on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [66][67][68][69]. Exosomes play a significant role in the paracrine effects of stem cells [70][71]. Exosomes from stem cells show low immunogenicity, low tumorigenicity, high transportation efficiency, innate stability, and the capacity to cross the BBB [72][73][74]. They have demonstrated beneficial effects by improving functional recovery after ischemic stroke, because of their ability to enhance brain plasticity [75][76]. Clinical evaluation of exosome therapeutics remains extremely limited, but promising efficacy has been observed in animal ischemic stroke models [77]. Doeppner et al. showed that exosomes from bone marrow MSCs (BMMSCs) efficiently reduced peripheral immunosuppression, enhanced neurovascular regeneration, and improved the motor function 4 weeks after ischemia [78]. MCAO (middle cerebral artery occlusion) rats achieved better results after with intravenous infusion of exosomes in foot fault and modified neurologic severity scores, compared to the PBS group [75]. Exosome treatment post stroke promoted neurite remodeling, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis [75]. Therapy based on exosomes from adipose-derived MSCs (ADMSCs) could reduce the brain infarct zone, improve the recovery of neurological function, and enhance fiber tract integrity and white matter repair in rats after stroke [79][80]. Numerous research studies illustrated that exosomes modulate the recipient cells and the rehabilitation process after stroke primarily via microRNAs (3.2. Exosomes and Ischemic Stroke Treatment

| [ | ||||||

| 93 | ||||||

| ] | ||||||

| [ | ||||||

| 98 | ||||||

| ] | ||||||

| miR-126 | ||||||

| MCAO-mouse | ||||||

| EPC | Neurogenesis | Angiogenesis Anti-apoptosis |

Caspase-3VEGFR2 | [95][96] | [100,101] | |

| miR-181b-5p | OGD-endothelial cell | MSC | Angiogenesis | TTRPM7 | [97] | [102] |

| miR-132 | zebrafish larvaeendothelial cell | Neuron | Angiogenesis | Cdh5/eEF2K | [52] | [54] |

| miR-124 | Photothrombosis mouse | MSC | Neurogenesis | GLI3 STAT3 |

[98] | [103] |

| MCAO-mouse OGD-neuron |

M2 microglia | Anti-apoptosis | USP14 | [99] | [104] | |

| miR-137 | MCAO-mouse OGD-neuron |

Microglia | Anti-apoptosis | Notch1 | [100] | [105] |

| miR-22-3p | MCAO-rat OGD-neuron |

MSC | Anti-apoptosis | KDM6B/BMP2/BMF axis | [101] | [106] |

| miR-34c | MCAO-rat OGD-neuroblastoma cells |

Astrocyte | Anti-inflammation Anti-apoptosis |

TLR7 and NFκB/MAPK pathways |

[102] | [107] |

| miR-146a-5p | MCAO-mouse OGD-microglia |

MSC | Anti-inflammation | IRAK1/TRAF6 pathway | [103] | [108] |