Fish is a major source of food and nutritional security for subsistence communities in developing countries, it also has linkages with the economic and supply-chain dimensions of these countries. ThIt is entry revealsed that COVID-19 has posed numerous challenges to fish supply chain actors, including a shortage of inputs, a lack of technical assistance, an inability to sell the product, a lack of transportation for the fish supply, export restrictions on fish and fisheries products, and a low fish price. These challenges lead to inadequate production, unanticipated stock retention, and a loss in returns. COVID-19 has also resulted in food insecurity for many small-scale fish growers. Fish farmers are becoming less motivated to raise fish and related products as a result of these cumulative consequences. Because of COVID-19’s different restriction measures, the demand and supply sides of the fish food chain have been disrupted, resulting in reduced livelihoods and economic vulnerability.

- aquaculture

- small-scale fisheries

- fish-based industry

- fish-food supply chain

- agri-food system

- fish farming

- agricultural vulnerability

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has had an influence on all sectors of the economy; the fisheries and aquaculture sector in particular has faced great difficulty, mainly due to the perishability of the product [2][1].

Fish is often a fishing community’s primary source of protein, fatty acids, and micronutrients [3][2]. Fish do not play a role in the transfer of COVID-19 to humans in terms of epidemiology. However, false perceptions about fish and the spread of COVID-19 have contributed to a decrease in the consumption of fish in some cases, such as in Bangladesh and China [4][3]. Because fish is an important food source for a large portion of the world’s population, the business of fishing requires changes, especially now during the current pandemic. Many of the governmental measures that have been introduced to limit the spread of COVID-19 have caused significant disruptions to human movement, physical business contact and the transport of goods [5][4].

By disrupting fish supply and demand, fish distribution, labor, and production, COVID-19 exposes the existing vulnerabilities in small-scale fisheries, putting small-scale farmers’ livelihoods at risk [7][5]. The many value chains within the fisheries and aquaculture sector were also subject to the inevitable disruptions to international and domestic transportation; these disruptions have affected the supply of raw materials for processing, the supply of production inputs, and the shipping of the finished products for both export and domestic consumption [8][6]. Farm-made inputs, such as seed stock and feed, have become unavailable due to the stringent restrictions that have been placed on the movement of materials and persons, including workers [9][7]. Small-scale fish farmers have lost money because they either had to sell off their fish or couldn’t sell their fish at all. Fish farmers could not harvest their fish in order to be able to begin a new production cycle, leading to a reduction in fish availability and the loss of downstream and upstream employment opportunities [7][5]. According to Waiho et al. [10][8], COVID-19 has depressed the demand for fish and fishery products and negatively impacted the supply chain, forcing hatcheries to close, feed imports to halt, and many value chain entities to lose money right from the start of the culture season. Medium and small businesses and seafood producers have been hit particularly hard, many of them are still unable to resume their normal operations [11][9]. COVID-19, in fact, has posed complex and long-term challenges for the aquaculture value chains’ continued operations and the livelihoods of the millions of people who rely on them [12][10]. However, the major impact on supply chains and demand is not from COVID-19 itself, but instead from the measures that have been introduced in order to control it.

2. Summary of the Impacts of COVID-19 on the Fisheries Sector

| Major Domains of Fisheries and Aquaculture Production | Impacts of COVID-19 | Sources | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders |

|

Fishing |

|

Stokes et al. [12][10] Ferrer et al. [9][7] Kumaran et al. [32][14] |

|

| Fiorella et al. [6][18] Campbell et al. [20][30] Ruiz-Salmón et al. [26][31] Paradis et al. [44][29] |

Freshwater aquaculture |

|

||

| Aquaculture production |

| Islam et al. [18][15] Seshagiri et al. [33][16] Cooke et al. [34][17] Fiorella et al. [6][18] Stokes et al. [12][10] |

|||

| Cooke et al. [34][17] Manlosa et al. [35][19] Sarà et al. [22][32] Islam et al. [18][15] |

Brackish water aquaculture |

|

||

| Processors |

| Kumaran et al. [32][14] Islam et al. [18][15] Manlosa et al. [35][19] |

|||

| White et al. | [ | 46][33] Bennett et al. [47][34] Fiorella et al. [6][18] Kumaran et al. [32][14] |

River and naturally sourced fisheries |

|

Waibel et al. [36][20] Newton et al. [14][21] Islam et al. [18][15] Stokes et al. [12][10] |

| Cold storage facilities |

|

Fahlevi et al. [48][35] Kumaran et al. [32][14] Kaewnuratchadasorn et al. [43][28] |

Offshore fisheries |

|

|

| Major Domains of Supply Chain | Impacts of COVID-19 | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Andrews et al. | [ | 37][22] Shenoy & Rajpathak [38][23] Marschke et al. [39][24] Asante, & Sabau [40][25] |

| Industry | Fernández-González, & Pérez-Vas | [41][26] Hasan et al. [42][27] Kaewnuratchadasorn et al. [4328] Paradis et al. [44][29] |

3. COVID-19’s Impacts on the Aquatic Food Supply Chain

The present study has identified several of the major impacts of COVID-19 on the aquatic food supply chain (Table 24. Impacts on Fisheries’ Production and Activity

4.1. The Negative Impacts

- Impact on fishing activity

- Impact on fishing activity

Fishing activity has decreased as a result of the social distancing practices and additional COVID-19 restrictions that have been implemented [18][15]. Since the World Health Organization proclaimed COVID-19 to be a pandemic, global industrial fishing activities have decreased by 10% or more in some areas, relative to the previous year’s average [3][2]. Fisheries were outlawed in several nations, such as India, as part of the mobility limitations that were imposed to counteract the developing pandemic [47][34].

- Impacts on aquaculture farms

Due to the significant drop in the market’s demand for fish and the limited transportation options that were available during the lockdown, fish farms have had difficulty in collecting and selling their goods [2][1]. As farmers have been unable to sell their products there has been an increase in live fish stock levels and a lengthening of the fish culture period, both of which have negatively impacted the feed conversion ratios, the ability to restock and, ultimately, the farms’ profitability.

4.2. Common Challenges Faced by Small-Scale Fisheries

5. Disruption to the Aquatic Food Supply Chain

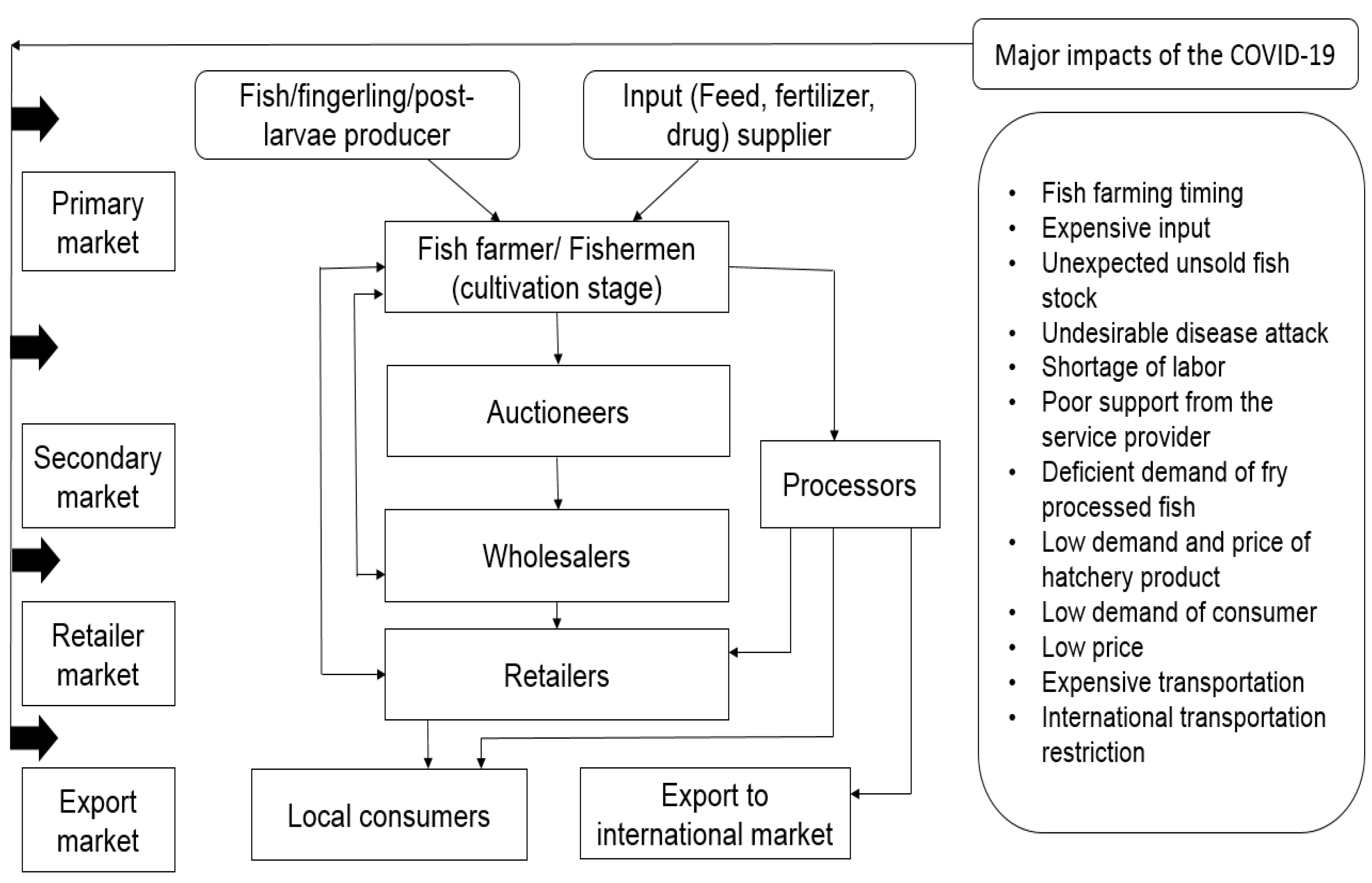

Global, regional, and local markets are all a part of the aquatic food supply chain. The operations required to transport fish and fish products from the supplier to the end consumer are extensive. Across the globe, the technologies used for this purpose range from traditional to highly industrial. The effects of COVID-19 have affected every activity in the supply chain (Figure 1). Within Figure 1, the bold arrows on the left side show the main points at which COVID-19 impacts the primary, secondary, retailer and export markets.

56. Policy Recommendations

- Smallholder fishers, whose livelihoods have been most heavily impacted by COVID-19, need food and cash for their survival and continued production. Loan forgiveness or new loans at subsidized rates for small-scale fishers and farmers could be included in the provision.

- The restoration of the fishing sector, including fishing activities, production, processing, and trade, can be aided by an emergency relief loan.

- The resumption of fresh product and seafood processing necessitates a relevant national agency’s safety and health inspection certification. Health and safety regulations must be implemented for fisheries’ products and processing facilities.

- The inability of smallholder fishers to sell their produce during the COVID-19 pandemic warrants the strengthening of the fish value chains, including the development of road and market infrastructure, cold storage facilities, transport systems, farmer to market linkages, and the increased flow of market information.

- The process of gaining knowledge from the losses and damages that have been incurred must be supported across all relevant institutions and sectors.

- Development organization can help with the re-orientation and flexibility of financing programs and the targeting of support to smallholders and rural fishing communities.

- The fishing season could be extended on a conditional basis.

References

- FAO. The Impact of COVID-19 on Fisheries and Aquaculture Food Systems, Possible Responses; FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-133768-4.

- FAO. Summary of the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Fisheries and Acquaculture Sector; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-132789-0.

- Mandal, S.C.; Boidya, P.; Haque, M.I.M.; Hossain, A.; Shams, Z.; Mamun, A.A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fish consumption and household food security in Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 29, 100526.

- Farrell, P.; Thow, A.M.; Wate, J.T.; Nonga, N.; Vatucawaqa, P.; Brewer, T.; Sharp, M.K.; Farmery, A.; Trevena, H.; Reeve, E.; et al. COVID-19 and Pacific food system resilience: Opportunities to build a robust response. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 783–791.

- Love, D.C.; Allison, E.H.; Asche, F.; Belton, B.; Cottrell, R.S.; Froehlich, H.E.; Gephart, J.A.; Hicks, C.C.; Little, D.C.; Nussbaumer, E.M.; et al. Emerging COVID-19 impacts, responses, and lessons for building resilience in the seafood system. Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 28, 100494.

- Giannakis, E.; Hadjioannou, L.; Jimenez, C.; Papageorgiou, M.; Karonias, A.; Petrou, A. Economic consequences of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) on fisheries in the eastern mediterranean (Cyprus). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9406.

- Ferrer, A.J.G.; Pomeroy, R.; Akester, M.J.; Muawanah, U.; Chumchuen, W.; Lee, W.C.; Hai, P.G.; Viswanathan, K.K. COVID-19 and small-scale fisheries in Southeast Asia: Impacts and responses. Asian Fish. Sci. 2021, 34, 99–113.

- Waiho, K.; Fazhan, H.; Ishak, S.D.; Kasan, N.A.; Liew, H.J.; Norainy, M.H.; Ikhwanuddin, M. Potential impacts of COVID-19 on the aquaculture sector of Malaysia and its coping strategies. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 18, 100450.

- Plagányi, É.; Deng, R.A.; Tonks, M.; Murphy, N.; Pascoe, S.; Edgar, S.; Salee, K.; Hutton, T.; Blamey, L.; Dutra, L. Indirect impacts of COVID-19 on a tropical lobster fishery’s harvest strategy and supply chain. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 1–14.

- Stokes, G.L.; Lynch, A.J.; Lowe, B.S.; Funge-Smith, S.; Valbo-Jørgensen, J.; Smidt, S.J. COVID-19 pandemic impacts on global inland fisheries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 29419–29421.

- Workie, E.; Mackolil, J.; Nyika, J.; Ramadas, S. Deciphering the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food security, agriculture, and livelihoods: A review of the evidence from developing countries. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 2, 100014.

- Simmance, F.A.; Simmance, A.B.; Kolding, J.; Schreckenberg, K.; Tompkins, E.; Poppy, G.; Nagoli, J. A photovoice assessment for illuminating the role of inland fisheries to livelihoods and the local challenges experienced through the lens of fishers in a climate-driven lake of Malawi. Ambio 2021.

- Belton, B. Impacts of COVID-19 on Aquatic Food Supply Chains in Egypt; CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems: Penang, Malaysia, 2020.

- Kumaran, M.; Geetha, R.; Antony, J.; Vasagam, K.P.K.; Anand, P.R.; Ravisankar, T.; Angel, J.R.J.; De, D.; Muralidhar, M.; Patil, P.K.; et al. Prospective impact of Corona virus disease (COVID-19) related lockdown on shrimp aquaculture sector in India—A sectoral assessment. Aquaculture 2021, 531, 735922.

- Islam, M.M.; Khan, M.I.; Barman, A. Impact of novel coronavirus pandemic on aquaculture and fisheries in developing countries and sustainable recovery plans: Case of Bangladesh. Mar. Policy 2021, 131, 104611.

- Seshagiri, B.; Nagireddy, M.; Raju, V.R.; Nagireddy, S.; Rangacharyulu, P.; Rathod, R.; Ratnaprakash, V. Impact of nationwide lockdown on freshwater aquaculture in Andhra Pradesh, India. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2020, 8, 377–384.

- Cooke, S.J.; Twardek, W.M.; Lynch, A.J.; Cowx, I.G.; Olden, J.D.; Funge-Smith, S.; Lorenzen, K.; Arlinghaus, R.; Chen, Y.; Weyl, O.L.F.; et al. A global perspective on the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on freshwater fish biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 253, 108932.

- Fiorella, K.J.; Bageant, E.R.; Mojica, L.; Obuya, J.A.; Ochieng, J.; Olela, P.; Otuo, P.W.; Onyango, H.O.; Aura, C.M.; Okronipa, H. Small-scale fishing households facing COVID-19: The case of Lake Victoria, Kenya. Fish. Res. 2021, 237, 105856.

- Manlosa, A.O.; Hornidge, A.K.; Schlüter, A. Aquaculture-capture fisheries nexus under COVID-19: Impacts, diversity, and social-ecological resilience. Marit. Stud. 2021, 20, 75–85.

- Waibel, H.; Grote, U.; Min, S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Praneetvatakul, S. COVID-19 in the greater Mekong Subregion: How resilient are rural households? Food Secur. 2020, 12, 779–782.

- Newton, R.; Zhang, W.; Xian, Z.; McAdam, B.; Little, D.C. Intensification, regulation and diversification: The changing face of inland aquaculture in China. Ambio 2021, 50, 1739–1756.

- Andrews, N.; Bennett, N.J.; Le Billon, P.; Green, S.J.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Amongin, S.; Gray, N.J.; Sumaila, U.R. Oil, fisheries and coastal communities: A review of impacts on the environment, livelihoods, space and governance. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 75.

- Shenoy, L.; Rajpathak, S. The Impact of COVID-19 on Fisheries and Aquaculture—A Global Assessment from the Perspective of Regional Fishery Bodies; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-132735-7.

- Marschke, M.; Vandergeest, P.; Havice, E.; Kadfak, A.; Duker, P.; Isopescu, I.; MacDonnell, M. COVID-19, instability and migrant fish workers in Asia. Marit. Stud. 2021, 20, 87–99.

- Asante, E.O.; Blankson, G.K.; Sabau, G. Building back sustainably: COVID-19 impact and adaptation in newfoundland and labrador fisheries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2219.

- Fernández-González, R.; Pérez-Pérez, M.I.; Pérez-Vas, R. Impact of the COVID-19 crisis: Analysis of the fishing and shellfishing sectors performance in Galicia (Spain). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169.

- Hasan, N.A.; Heal, R.D.; Bashar, A.; Bablee, A.L.; Haque, M.M. Impacts of COVID-19 on the finfish aquaculture industry of Bangladesh: A case study. Mar. Policy 2021, 130, 104577.

- Kaewnuratchadasorn, P.; Smithrithee, M.; Sato, A.; Wanchana, W.; Tongdee, N.; Sulit, V.T. Capturing the Impacts of COVID-19 on the Fisheries Value Chain of Southeast Asia. Fish People 2020, 18, 2–8. Available online: http://repository.seafdec.org/handle/20.500.12066/6557 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Paradis, Y.; Bernatchez, S.; Lapointe, D.; Cooke, S.J. Can you fish in a pandemic? An overview of recreational fishing management policies in North America during the COVID-19 crisis. Fisheries 2021, 46, 81–85.

- Campbell, S.J.; Jakub, R.; Valdivia, A.; Setiawan, H.; Setiawan, A.; Cox, C.; Kiyo, A.; Darman; Djafar, L.F.; Rosa, E.; et al. Immediate impact of COVID-19 across tropical small-scale fishing communities. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 200, 105485.

- Ruiz-Salmón, I.; Fernández-Ríos, A.; Campos, C.; Laso, J.; Margallo, M.; Aldaco, R. Fishing and seafood sector in the time of COVID-19: Considerations for local and global opportunities and responses. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 23, 100286.

- Sarà, G.; Mangano, M.C.; Berlino, M.; Corbari, L.; Lucchese, M.; Milisenda, G.; Terzo, S.; Azaza, M.S.; Babarro, J.M.F.; Bakiu, R.; et al. The synergistic impacts of anthropogenic stressors and COVID-19 on aquaculture: A current global perspective. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2021, 1–13.

- Zabir, A.A.; Mahmud, A.; Islam, M.A.; Antor, S.C.; Yasmin, F.; Dasgupta, A. COVID-19 and Food Supply in Bangladesh: A Review. South Asian J. Soc. Stud. Econ. 2021, 10, 15–23.

- Bennett, N.J.; Finkbeiner, E.M.; Ban, N.C.; Belhabib, D.; Jupiter, S.D.; Kittinger, J.N.; Mangubhai, S.; Scholtens, J.; Gill, D.; Christie, P. The COVID-19 pandemic, small-scale fisheries and coastal fishing communities. Coast. Manag. 2020, 48, 336–347.

- Fahlevi, H.; Chan, S.; Hasibuan, P.; Fadli, N.; Sofyan, S.E.; Rianjuanda; Syukri, M.; Saidi, T.; Dawood, R. The feasibility of a cold storage facility for fish in Aceh during the COVID-19 pandemic. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 674, 012047.

- Iese, V.; Wairiu, M.; Hickey, G.M.; Ugalde, D.; Hinge Salili, D.; Walenenea, J.; Tabe, T.; Keremama, M.; Teva, C.; Navunicagi, O.; et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on agriculture and food systems in Pacific Island countries (PICs): Evidence from communities in Fiji and Solomon Islands. Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103099.

- OECD. COVID-19 Pandemic: Towards a Blue Recovery in Small Island Developing States; OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 1–29. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1060_1060174-tnkmsj15ap&title=COVID-19-pandemic-Towards-a-blue-recovery-in-small-island-developing-states (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Gatto, M.; Islam, A.H.M.S. Impacts of COVID-19 on rural livelihoods in Bangladesh: Evidence using panel data. PLoS ONE 2021, in press.