Child labour is nconsidered a visible and the most common form of child abuse and neglect in developing countries and based on the above, the present research focuses on the association between child labour and the pandemics in the developing countries, including the COVID-19 pandemic. The present research

cludes activities that deprive minors of their childhood, potential and dignity and conculudes that previous studies on non-COVID-19 pandemics have mainly focused on the African

d negatively affeconomies, while studies on the recent pandemic have focused on Asian countries their mental and physical developmen.

- child labour

- developing countries

- pandemics

- epidemics

- COVID-19

1. Introduction

Previous studies have focused on the impact of pandemics and health crises on the welfare of children. Lockdowns during pandemics increase the reported cases of child abuse and neglect and the loss of parental support worldwide ( Douglas et al. 2009 ; Jentsch and Schnock 2020 ; Rodriguez et al. 2021 ). Nevertheless, during pandemics, the social protection of children has been judged as inadequate, as in the case of the H1N1 flu ( Douglas et al. 2009 ; Murray 2010 ). In general, pandemics create conditions under which the maltreatment, abuse and neglect of children are enabled ( Rodriguez et al. 2021 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic has attracted research interest over the past few months that has mostly focused on its socio-economic consequences worldwide ( Aneja and Ahuja 2020 ; Ali et al. 2020 ; Nicola et al. 2020 ). It has been estimated that COVID-19 will mainly affect the well-being of vulnerable groups, including children ( Armitage and Nellums 2020 ). The UN Committee of the Rights of the Child highlighted the importance of investigating the impact of the recent pandemic on children’s human rights, including health issues, their well-being and development, as well as the problem of child labour ( Campbell et al. 2021 ; Lee 2021 ). Therefore, the estimated effects of COVID-19 on child labour merit attention and this should be a top research priority considering the vulnerability of minors to child labour. In particular, according to Zahed et al. ( 2020) the case of children when investigating the consequences of COVID-19 is often neglected, even though they are a vulnerable social group. Apart from the psychological and physical consequences of COVID-19, the researchers concluded that working children are more susceptible to the infection and that the pandemic has increased poverty, which is a contributing factor to child labour.

The recent pandemic is expected to increase the risks for vulnerable social groups including children and it could lead to higher rates of child labour, exploitation, forced labour and slavery ( Ahad et al. 2020 ; Rafferty 2020 ; Raman et al. 2020 ). These findings are in line with Gupta and Jawanda ( 2020), who argued that the pandemic will increase economic insecurity and child exploitation, including child labour, mainly in poor regions. Similarly, the pandemic is expected to lead to an economic crisis and to increase child poverty, which is a determinant of child labour ( Goldman et al. 2020 ; Van Lancker and Parolin 2020 ). Ghosh et al. ( 2020a ) also argued that the recent pandemic has had a significant psychological impact on children. According to the researchers, COVID-19 is expected to increase child abuse and domestic violence, as well as child labour and exploitation.

The impact of previous pandemics (e.g., Ebola, SARS, HIV/AIDS, H1N1, Influenza) on the well-being of minors has been the subject of previous studies ( Holmberg 2017 ; Shelley-Egan and Dratwa 2019 ). Nevertheless, the economic exploitation of children during health crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic, remains under investigated. Therefore, the present paper represents the first effort to conduct an extended literature review on empirical papers that have studied the association between pandemics and child labour in developing countries, including the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Definition of Child Labour

The past decades have witnessed various efforts by international and local organizations in the fight against the phenomenon of child labour. The present research focuses on minor employees in developing countries and argues that they have higher rates of child labour ( Scanlon et al. 2002 ), including contributing family workers ( Diallo et al. 2013 ). Child labour includes the violation of the human rights of minors and it is associated with various harmful activities ( Edmonds and Pavcnik 2005 ). Several definitions of child labour have been presented to date, ranging from wage work for minors ( Psacharopoulos 1997 ) and various forms of market work ( Ray and Lancaster 2005 ) to domestic activities ( Basu et al. 2010 ; Assaad et al. 2010 ). These findings are in line with Levison and Moe ( 1998) and Webbink et al. ( 2012), who also defined domestic activities as a “hidden” form of child labour. According to Basu ( 1999), child labour could be either paid or not paid and it is associated with domestic activities.

Similarly, according to the ILO/IPEC ( 2021), child labour should not be confused with child work. In particular, child labour includes activities that deprive minors of their childhood, potential and dignity and could negatively affect their mental and physical development; it is therefore harmful to minors. Based on the ILO Minimum Age Convention ( ILO 1973, No. 138 ), minors should be older than 15 to legally participate in the labour force ( ILO 1973 ). UNICEF has further extended the above presented definitions and focuses on the importance of both domestic and economic work. In particular, child labour refers to minors aged 5–11 engaged in any economic activity or at least 28 h of domestic activities, minors aged 12–14 engaged in any economic activity, excluding light work for no more than 14 h weekly and minors aged 15–16 engaged in any hazardous work ( UNICEF 2007 ). Therefore, it is concluded that there is no single universally accepted definition of the phenomenon. Finally, the ILO/IPEC ( 2021) observed that in order to define “work” as child labour several factors should be considered, including the age, the hours and the type of work, the working conditions and the objectives.

Several international organizations provide country-level data on child labour, including the ILO, the World Bank, the United Nations and UNICEF, as well as child labour indicators (e.g., ILO’s indicator on the Proportion and Number of Children aged 5–17 years engaged in Child Labour, UNICEF’s indicator on the Percentage of Children aged 5–17 years engaged in Child Labour etc.), while certain previous studies have used the secondary school non-enrollment rates as a proxy for child labour ( Kucera 2002 ; Busse and Braun 2004 ; Braun 2006 ; Beegle et al. 2009 ), although several minor employees go to school and it is argued that school enrolment and child labour are not incompatible activities; therefore, combining child labour and school enrolment is feasible but difficult ( Ravallion and Wodon 2000 ; Attanasio et al. 2010 ; Edmonds and Shrestha 2014 ).

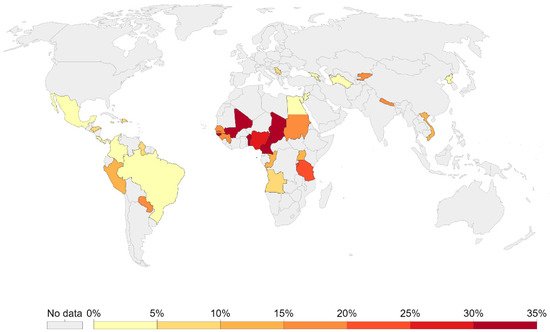

Finally, as for the regional distribution of child labour, according to the United Nations, rates are higher in the Sub-Saharan economies ( Figure 1 ). The problem has been mainly attributed to high poverty rates in the region ( Canagarajah and Nielsen 2001 ; Admassie 2002 ; Chukwudeh and Oduaran 2021 ), poor school quality ( Ray 2002 ; Rena 2009 ) and social conditions in post-war African countries ( Hilson 2010 ; Maconachie and Hilson 2016 ). Similarly, for the period 2010–2018, the Sub-Saharan African countries had the highest percentage of children aged 5–17 engaged in child labour, estimated at 29% ( UNICEF 2019a ).

3. Studies on Child Labour and Previous Non-COVID-19 Pandemics in Developing Countries

Child labour is considered a visible and the most common form of child abuse and neglect in developing countries ( Caesar-Leo 1999 ; Maruf et al. 2003 ; Mahmod et al. 2016 ) and based on the above, the present research focuses on the association between child labour and the pandemics in the developing countries, including the COVID-19 pandemic. In several developing countries, pandemics push minors into the labour markets ( Grier 2004 ; Deb 2005 ). Therefore, an in-depIth systematic literature review w was conducted using reliable databases, (e.g., Sciencedirect, Scopus, Google Scholar, NCBI etc.). The key terms used during the research were “child labor”, “child labour”, “epidemic”, “pandemic”, as presented in Table 1 . It is noted that scientific peer-journal articles were included that were published in English and that focused on developing countries, as well as reports from international organizations, such as the UNICEF, the ILO etc. Thus, books and conference proceedings were excluded.

| Keyword(s) | Synonym or Variations |

|---|---|

| Child labour | Child labor, minor employees, working children, child labor force, child labourer, child laborer, employment of children, labour of children |

| Pandemic | Epidemic, contagious diseases, Ebola, SARS, HIV/AIDS |

| Developing countries | Developing economies, low-and-middle income countries, emerging economies, emerging countries, developing nations, Third World |

It could be argued that previous pandemics in developing economies exacerbated the existing issues of child exploitation and labour, while gendered responsibilities were observed. Moreover, previous studies focused on paid child labour and it is argued that non-paid work could be characterised as invisible and difficult to estimate. Among the above presented studies, Sorsa and Abera ( 2016) were the first to study child labour and malaria as a type of pandemic. However, their study did not focus exclusively on the association between the two variables, but mainly on children that worked in regions in which malaria was endemic. Lugalla and Sigalla ( 2010) argued that in Tanzania there was little awareness of working children, mainly in rural areas. They suggested that the government and international organizations should cooperate to reduce rural poverty and therefore eliminate child labour.

Furthermore, among the included studies, it was observed that the African economies, in which child labour rates are high, have attracted increased research interest ( Canagarajah and Nielsen 2001 ; Maconachie and Hilson 2016 ). According to thCe literature review findings, certrtain studies and reports (e.g., Save the Children/UNICEF/World Vision/Plan International 2015 ; Ngegba and Mansaray 2016 ; Yoder-van den Brink 2019 ; Smith 2020 ) studied the impact of pandemics on child labour in post -war countries, as in the case of Sierra Leone. It was concluded that pandemics could deter the so-called crisis of youth in Sierra Leone and it was argued that several minors end up in informal or unskilled labour ( Peters 2011 ; Maconachie and Hilson 2016 ).

To summarise, there is evidence to support the claim that there is an important research gap on child labour in Latin America during pandemics, which should be confronted since minor employees remain a major social issue in the region. It is interesting that several Latin American countries were affected by pandemics over the past decades, including the outbreak of cholera in the ‘90s ( Kumate et al. 1998 ; Poirier et al. 2012 ), which affected other countries with high rates of child labour, such as Brazil, Bolivia and Venezuela ( Psacharopoulos 1997 ; Silva et al. 2019 ; Costa et al. 2020 ). Therefore, the present study concludes that there is a research gap regarding child labour and pandemics in the region.

4. Studies on COVID-19 and Child Labour in Developing Countries

Based on the above presented procedure, the additional terms “COVID-19” and “SARS-COV-2” were included as keywords. Therefore, the keywords used in thise analysis were: “child labor”, “child labour”, “epidemic”, “pandemic”, “COVID-19” and “SARS-COV-2”. The results of the final search are presented in Table 32 . It is noted that the included papers were based on secondary data and literature reviews.

| Author(s) | Case | Sample | Methodology | Results and Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chopra (2020) | COVID-19 | India | Literature review | Child protection services in the country are not fully functional. Children in the country, mainly street and abandoned children, receive limited support, which increases the risks of child abuse and labour. |

| Greenbaum et al. (2020) | COVID-19 | Not defined | Literature review | The recent pandemic could increase human trafficking and labour exploitation. Minors are more likely to engage in hazardous or illegal activities and work in unhealthy working conditions. |

| Larmar et al. (2020) | COVID-19 | Nepal | Literature review | Recovery programs should be applied in the country in order to build capacity and strengthen cooperation among social workers, non-governmental organizations, health professionals and community-based organizations. |

| Owusu and Frimpong-Manso (2020) | COVID-19 | Ghana | Literature review | The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to have severe socioeconomic consequences, mainly for poor families. As a result, poor children are more likely to be left homeless and be forced to work. |

| Progga et al. (2020) | COVID-19 | Bangladesh | Literature review | Child labour should be effectively detected and prevented. A dataset on child labour would be an effective solution in Bangladesh and in other countries of the region, including India, Nepal and Pakistan. |

| Nguyen et al. (2020) | COVID-19 | Vietnam | Literature review | It is estimated that the pandemic could lead to severe socioeconomic problems, including increased exploitation and child labour, higher dropout rates and malnutrition. |

| Ramaswamy and Seshadri (2020) | COVID-19 | India | Literature review | Lockdown during the recent pandemic and the arising economic issues are expected to increase child abuse, trafficking and maltreatment, including child labour. The study concluded that attention should be paid to the likely psychosocial and mental health issues for children as a result of the pandemic. |

| ILO/UNICEF (2020) | COVID-19 | Not defined | Literature review | The research concluded that the recent pandemic could affect child labour through reducing employment opportunities, living standards, remittances and migration and international aid flows. Additional channels that could influence child labour were increased informal child labour, reduced Foreign Direct Investment and school closures. |

| The World Bank Group (2020) | COVID-19 | Not defined | Literature review | The COVID-19 pandemic will lead to a shock to education, resulting in higher dropout rates, which are linked to higher rates of child labour. |

| United Nations/DESA (2020) | COVID-19 | Not defined | Literature review | School closures as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with higher child labour rates and maltreatment. |

| Kaur and Byard (2021) | COVID-19 | India | Literature review | The potential consequences of COVID-19 include an economic crisis, which would mainly affect children. India has severe gaps in the protection services and therefore minors are more vulnerable to child labour and exploitation. |

| Sserwanja et al. (2021) | COVID-19 | Uganda | Literature review | The pandemic had a significant negative impact on the children’s health status and food care. The country has insufficient social support systems which rendered children even more vulnerable to child abuse, including child labour and limited financial support. |

| Daly et al. (2021) | COVID-19 | Nepal | Literature review | Nepalese children are more vulnerable to poverty, poor health, including COVID-19 contamination and educational exclusion. |

| Pattanaik (2021) | COVID-19 | India | Literature review | The study concludes that the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to have a significant negative impact on the country’s economy and on the labour market imperfections, leading to higher child labour rates. |

The studies lead to the common argument that the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to lead to an employment crisis in developing countries, which will lead to higher percentages of child labour. As for the methodological approach, it was observed that all of the included papers were based on a literature review and on secondary data. Except for the study of Greenbaum et al. ( 2020), the researchers focused on the cases of specific countries rather than on a group of countries. The case of India was dominant and it has been studied by four researchers to date, who were motivated by the increased demand for cheap labour force in the country and high poverty rates in the country ( Kaur and Byard 2021 ). On the contrary, Sserwanja et al. ( 2021) focused on the case of Uganda, which was motivated by the increase in children abuse incidents in the county during the pandemic.

In particular, the majority of the above presented studies turned their orientation towards child labour and COVID-19 in the Asian developing countries. Therefore, it is observed that to date there is no published research regarding the case of the Latin American and the Caribbean countries, while there is decreasing research interest in the African developing countries compared to previous pandemics and health crises. This could be attributed to the characteristics of several Asian countries that render children more vulnerable to the disease, including population density, poor health systems and insufficient testing, which led to research interest in COVID-19 and its consequences to the region ( Sarkar et al. 2020 ; Stone 2020 ; Alam 2021 ).

Finally, the reports of international organizations on child labour and COVID-19 (e.g., ILO/UNICEF 2020 ; United Nations/DESA 2020 ; The World Bank Group 2020 ) reached the common conclusion that the current pandemic could reverse the positive trends and increase child labour worldwide. This rise is attributed to the disruption in supply chains and to higher commodity prices. School closures, dropout rates, limited employment opportunities, failing living standards and trading activity in the post-COVID-19 period are listed among the channels of child labour during the pandemic. It is noted that Ghosh et al. ( 2020a ) also concluded that COVID-19 is expected to increase child labour; nevertheless, their research did not focus on developing countries and thus the study was excluded from the above presented table.

References

- United Nations Statistics Division. 2021. Child Labor. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/child-labor (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Chopra, Geeta. 2020. Covid-19 disrupts India’s March towards making her children thrive and transform. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 10: 184–88.

- Greenbaum, Jordan, Hanni Stoklosa, and Laura Murphy. 2020. The public health impact of coronavirus disease on human trafficking. Frontiers in Public Health 8.

- Larmar, Stephen, Merina Sunuwar, Helen Sherpa, Roopshree Joshi, and Lucy P. Jordan. 2020. Strengthening community engagement in Nepal during COVID-19: Community-Based training and development to reduce child labour. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development 31: 23–30.

- Owusu, Lorretta D., and Kwabena Frimpong-Manso. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on children from poor families in Ghana and the role of welfare institutions. Journal of Children’s Services 15: 185–90.

- Progga, Farhat T., Tanzil M. Shahria, Asma Arisha, and Minhaz Shanto. 2020. A deep learning based approach to child labour detection. Paper presented at 6th Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS), Surabaya, Indonesia, October 14–16; pp. 24–29.

- Nguyen, Huong T. T., Tham T. Nguyen, Vu A. T. Dam, Long H. Nguyen, Giang T. Vu, Huong L. T. Nguyen, Hien T. Nguyen, and Huong T. Le. 2020. COVID-19 employment crisis in Vietnam: Global issue, National solutions. Frontiers in Public Health 8.

- Ramaswamy, Sheila, and Shekhar Seshadri. 2020. Children on the brink: Risks for child protection, sexual abuse and related mental health problems in the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 62: S404–13.

- ILO/UNICEF. 2020. COVID-19 and Child Labour: A Time of Crisis, a Time to Act. Briefing Paper. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/70261/file/COVID-19-and-Child-labour-2020.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- The World Bank Group. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Shocks to Education and Policy Responses. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33696/148198.pdf?sequence=4andisAllowed=y (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- United Nations/DESA. 2020. Responses to the COVID-19 Catastrophe Could Turn the Tide on Inequality. Available online: https://olc.worldbank.org/system/files/PB-65.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Kaur, Navpreet, and Roger W. Byard. 2021. Prevalence and potential consequences of child labour in India and the possible impact of COVID-19—A contemporary overview. Medicine Science and the Law.

- Sserwanja, Quraish, Joseph Kawuki, and Jean Kim. 2021. Increased child abuse in Uganda amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 57: 188–91.

- Daly, Angela, Alyson Hillis, Shubhendra Man Shrestha, and Babu Kaji Shrestha. 2021. Breaking the child labour cycle through education: Issues and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children of in-country seasonal migrant workers in the brick kilns of Nepal. Children’s Geographies, 1–7.

- Pattanaik, Ipsita P. 2021. Corona virus, child labour and imperfect market in India. EPRA International Journal of Economic and Business Review 9.