BC is a complex disease with miscellaneous morphologic and biological features and, hence, various clinical courses and prognoses

[5]. The traditional classification of BC is based on tumor stage and grade. The TNM staging system by the American Joint Committee on Cancer encompasses both clinical and pathologic data on tumor size (T), the status of regional lymph nodes (N), and distant metastases (M); subsequently, based on these data, the disease is established as being in one of five stages (0–IV)

[5]. Tumor grade brings information on cell differentiation—it includes evaluation of the particular features of the cell, which include tubule formation, size and shape of the nucleus in tumor cells, and mitotic rate

[5]. With more than 20 different histologic types; BC can be classified based on clinicopathologic features such as cell type of the tumor, extracellular secretion, architectural features, or immunohistochemical profile. The most common type is invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified (IDC-NOS), which is found in 70–80% of cases. It encompasses adenocarcinomas that cannot be classified as one of the special types

[5][6][5,6]. The most common among special types of BC is invasive lobular carcinoma, accounting for about 10% of cases. Other less common special types include: tubular, cribiform, mucinous, papillary, apocrine, medullary, metaplastic, or mixed type carcinomas

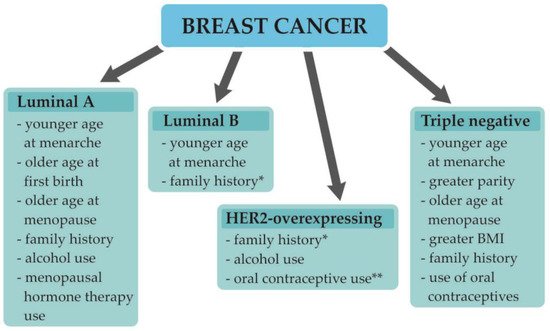

[5][6][5,6]. In recent decades, there has been meaningful development in the understanding of BC biology, which has led to the conclusion that the previous classifications do not display the heterogeneity of the disease—both response to therapy and prognosis are defined by the biological features of a tumor

[5][7][5,7]. Routine immunohistochemical analysis of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and Ki-67 expression (proliferation index) is currently used to determine the four basic molecular subtypes of BC: Luminal A-like, luminal B-like, HER2-overexpresing, and triple-negative BCs. This classification (approved by the St Gallen Consensus Conference) facilitates choosing the right therapeutic approach and allows to determine a patient’s future outcome

[5][8][5,8]. Apart from the molecular subtype of BC, the TNM stage and the patient’s preferences, as well as many other factors, play a role in choosing the most personalized therapy. The clinico-prognostic characteristics of particular subtypes are shown in

Table 1. The first-line therapy for the early BC combines surgery and postoperative radiation. Main surgical approaches include mastectomy or an excision followed by radiation. Breast cancer surgery may also include dissection of axillary lymph nodes if there are indications for the procedure. Furthermore a pre- (neoadjuvant) or postoperative (adjuvant) systemic therapy may be administered, which includes chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or trastuzumab-based therapy. In metastatic disease, the major objectives are prolongation and maintaining quality of life. The systemic therapy encompasses chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, trastuzumab-based therapy, or other targeted therapies such as CDK4/6 inhibitor or PARP inhibitor

[9]. In some patients, breast surgery may be implemented as it could improve local progression free survival; however, it may worsen distant progression free survival. There is no evidence that surgical treatment of the primary tumor improves overall survival in metastatic disease

[10].