Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Mohammed S Salahudeen and Version 3 by Beatrix Zheng.

Healthcare practitioner-oriented interventions have the potential to reduce the occurrence of anticholinergic prescribing errors in older people. Interventions were primarily effective in reducing the burden of anticholinergic medications and assisting with deprescribing anticholinergic medications in older adults.

- anticholinergics

- intervention

- prescribing

- older people

1. Introduction

Prescribing medications among older adults is recognised as a challenging task and an essential practice that needs to be continuously monitored, assessed, and refined accordingly. Moreover, it is based on understanding clinical pharmacology principles, knowledge about medicines, and particularly the experience and empirical knowledge of the prescribers [1][2][1,2]. Clinicians face several challenges while prescribing medications among older adults, and the prescribing of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) for this age group is prevalent [3]. The available epidemiological data show that up to 20% of older patients in outpatient settings and 59% of hospitalised older patients consume at least one PIM [4][5][6][7][8][4,5,6,7,8]. Adverse effects in older people due to inappropriate prescribing are prevalent, leading to increased hospital admissions and mortality [9].

Medications that possess anticholinergic activity are a class of PIMs widely prescribed for various clinical conditions in older adults [10][11][10,11]. Older people are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects from medicines with anticholinergic-type effects [12][13][12,13]. Most medications commonly prescribed to older people are not routinely recognised as having anticholinergic activity, and empirically, clinicians prescribe these medicines based on their anticipated therapeutic benefits while overlooking the risk of cumulative anticholinergic burden [14][15][16][14,15,16]. Anticholinergic burden refers to the cumulative effect of taking multiple medications with anticholinergic activity [17][18][17,18]. There is no gold standard approach available to quantify and determine whether an acceptable range of anticholinergic drug burden exists in older adults [19][20][19,20]. The central adverse effects of anticholinergic medications are attributed to the excess blocking of cholinergic receptors within the central nervous system (CNS) [16]. The commonly reported central adverse effects are cognitive impairment, headache, reduced cognitive function, anxiety, and behavioural disturbances [16]. The common peripheral adverse effects of anticholinergic medications are hyperthermia, reduced saliva and tear production, urinary retention, constipation, and tachycardia [16].

Anticholinergic medications are associated with poor outcomes in older patients, but there is no specific intervention strategy for reducing anticholinergic drug exposure [21]. There is little evidence that medication review could be a promising strategy in reducing the drug burden in older people [22][23][22,23]. Medical practitioner-led and pharmacist-led medication reviews have earlier been reported as a standard practice for reducing anticholinergic drug exposure [24][25][24,25]. Pharmacist-led medication review has recently been found to be ineffective among older patients of the Northern Netherlands [25]. A few meta-analyses have also reported the lack of effectiveness of different types of medication reviews on mortality and hospitalisation outcomes [26][27][28][26,27,28]. Multidisciplinary strategies such as patient-centred, pharmacist–physician intervention are also recognised as promising for improving medication use in older patients at risk [29]. Another intervention strategy, i.e., the SÄKLÄK project, had some effects on the PIMs prescription and reduced potential medication-related problems [30]. The SÄKLÄK project is a multi-professional intervention model to improve medication use in older people [30], and it consists of self-assessment using a questionnaire, peer-reviewed by experienced healthcare professionals, feedback report provided by experienced healthcare professionals, and an improvement plan [30].

Interventions to improve prescribing practice more generally have been the subject of many studies and are frequently targeted according to the type of error [31][32][31,32]. It is crucial to explore which interventions have effectively changed prescribing practices and optimised patient outcomes while minimising healthcare costs. However, little is known about the effectiveness of existing interventions at improving the anticholinergic prescribing practice for older adults.

2. Analysis on Research Results

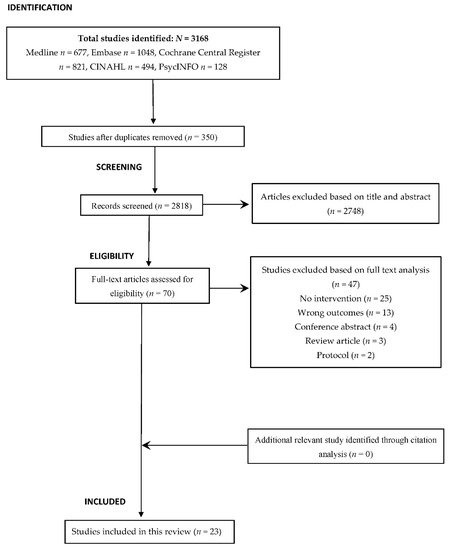

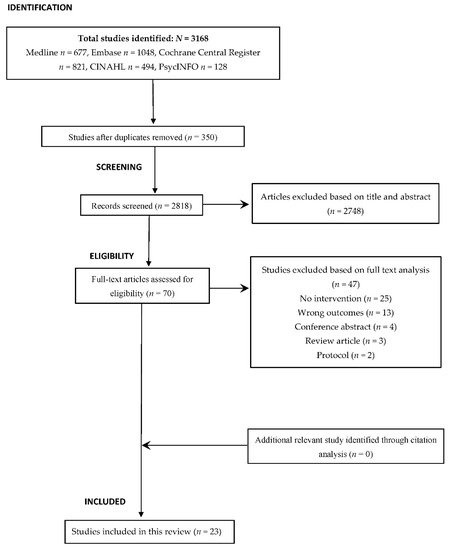

The primary electronic search identified a total of 3168 studies from the five databases. Using EndNote X9 (Thomson Reuters), we eliminated 350 duplicate studies, and the remaining 2818 studies were examined to determine their relevance for inclusion. Of those, only 70 were found to be eligible for full-text analysis. Subsequently, 47 studies were excluded as they failed to meet the predefined inclusion criteria. No potential studies were identified from the citation analysis. Finally, a total of 23 studies that investigated the effectiveness of anticholinergic prescribing practice in older adults were included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process and citation analysis.

2.1. Overview of the Included Studies

2.1. Overview of the Included Studies

Table 1 provides the qualitative summary of the included studies, mainly showcasing the type of interventions, and Table 2 illustrates an overview of the quantitative summary of the studies based on study design, setting, sample size, study duration and follow-up, outcome measure (control/pre and intervention/post), significant association (+ or −), and statistical tests.

The countries of origin were USA (n = 5) [29][33][34][35][36][29,38,39,40,41], Australia (n = 4) [22][23][37][38][22,23,42,43], Finland (n = 2) [39][40][44,45], Norway (n = 2) [21][41][21,46], Ireland [42][47], New Zealand [43][48], Belgium [44][49], Spain [45][50], Sweden [46][51], Sweden [30], France [47][52], Italy [48][53], Taiwan [49][54], and The Netherlands [50][55].

The study settings included hospitals (n = 7) [35][36][39][41][45][47][48][40,41,44,46,50,52,53] community/primary care (n = 7) [22][30][33][42][44][46][50][22,30,38,47,49,51,55] and nursing homes/aged care facilities (n = 9) [21][23][29][34][37][38][40][43][49][21,23,29,39,42,43,45,48,54]. There were ten cross-sectional studies [22][33][35][37][38][39][41][46][47][49][22,38,40,42,43,44,46,51,52,54], six nonrandomised or pre/post studies [30][34][42][43][45][48][30,39,47,48,50,53], and seven RCTs [21][23][29][36][40][44][50][21,23,29,41,45,49,55]. The studies included in this study had sample sizes ranging from 46 to 46,078 study subjects. The average age of the participants varied between 65 and 87.5 years, and the proportion of the female subjects was 39.0–77%.

The qualitative summary of included studies.

The quantitative summary of included studies.

Table 1. The qualitative summary of included studies.

| Author, Year, Country | Study Design | Intervention | Description of Intervention(s) | Effect on Outcome/Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riordan et al., 2019, Ireland [42] | Convergent parallel mixed-methods design (before and after) | Academic Detailing (pharmacist-led) | Pharmacist conducted face-to-face education sessions and small focus group academic detailing sessions of 19–48 min with physicians. |

Pharmacist-led academic detailing intervention was acceptable to GPs. Behavioural Change: awareness of non-pharmacological methods in treating urinary incontinence. Knowledge Gain: intervention served to refresh their knowledge |

| Ailabouni et al., 2019, New Zealand [43] | A single group (pre-and post-comparison) feasibility study | Medication review (deprescribing) | A collaborative pharmacist-led medication review with GPs was employed. New Zealand registered pharmacists used peer-reviewed deprescribing guidelines. The cumulative use of anticholinergic and sedative medicines for each participant was quantified using the DBI. |

Deprescribing resulted in a significant reduction in falls, depression and frailty scores, and adverse drug reactions. No improvement in cognition and quality of life. Total regular medicines use reduced statistically, by a mean difference of 2.13 medicines per patient, among patients where deprescribing was initiated. |

| Toivo et al., 2019, Belgium [44] | Cluster RCT | Care coordination intervention (coordinated medication risk management) | Practical nurses were trained to make the preliminary medication risk assessment during home visits and report findings to the coordinating pharmacist. The coordinating pharmacist prepared the cases for the triage meeting with the physician and home care nurse to decide further actions. | No significant impact on the medication risks between the intervention and the control group. The per-protocol analysis indicated a tendency for effectiveness, particularly in optimising central nervous system medication use. |

| Hernandez et al., 2020, Spain [45] | Prospective pre-and post- interventional study | Medication review | Pharmacists reviewed the medications and detected drug-related problems using the Drug Burden Index (DBI) tool. Their recommendations were communicated to the physician via telephone, weekly meetings, and email. Further review was conducted at the weekly meeting between physician and pharmacist. | Statistically significant differences were found between pre- and post-intervention in NPI at admission, drug-related problems, MAI criteria (interactions, dosage and duplication), and mean (SD) DBI score. |

| Lenander et al., 2018, Sweden [46] | Cross-sectional | Medication Review | Clinical Pharmacist led medication review to assess the prevalence of DRPs and recommendations to discontinue, followed by team-based discussions with general practitioners (GPs) and nurses | It shows that the medication reviews decreased the use of potentially inappropriate medication. |

| Weichert et al., 2018, Finland [39] | Multicentre observational study | Medication Review | Medication review was conducted for ACB in patients at the time of admission and discharge | 21.1% of patients had their ACB reduced. There is considerable scope for improvement of prescribing practices in older people. |

| Lenander et al., 2017, Sweden [30] | Interventional pilot study | SÄKLÄK project, a developed intervention model | Multi-professional intervention model created to improve medication safety for elderly | Significant decrease in the prescription of anticholinergic drugs indicated the SÄKLÄK intervention is effective in reducing potential DRPs |

| Moga et al., 2017, USA [29] |

Parallel arm Randomised Interventional study | Targeted medication therapy management intervention | Targeted patient-centred pharmacist–physician team medication therapy management intervention was used to reduce the use of inappropriate anticholinergic medications in older patients. | The targeted medication therapy management intervention resulted in improvement in anticholinergic medication appropriateness and reduced the use of inappropriate anticholinergic medications in older patients. |

| Lagrange et al., 2017, France [47] | Retrospective study | A context-aware pharmaceutical analysis tool | A context-aware computerised decision-support system designed to automatically compare prescriptions recorded in computerised patient files against the main consensual guidelines for medical management in older adults. | Prescription of anticholinergics was significantly decreased (28%). |

| Carnahan et al., 2017, USA [34] | Quasi-experimental study design | Educational program on medication use | IA-ADAPT/CMS Partnership is an evidence-based training program to improve dispensing drugs for elderly | Suggests that the IA-ADAPT and the CMS Partnership improved medication use with no adverse impact on BPSD. |

| Hanus et al., 2016, USA [35] | Observational Pilot study | Pharmacist-led EHR-based population health initiative and ARS Service | Physicians in the primary care settings could communicate with pharmacists employing a shared EHR. As part of a quality improvement project, a pharmacist-led EHR-based medication therapy recommendation service was implemented at 2 DHS medical clinics to reduce the anticholinergic burden |

High recommendation acceptance rates were achieved using objective anticholinergic risk assessment and algorithm-driven medication therapy recommendations. |

| McLarin et al., 2016, Australia [38] | Retrospective study | RMMR | Impact of RMMRs on anticholinergic burden quantified by seven anticholinergic risk scales | Demonstrated that RMMRs are effective in reducing ACM prescribing in elderly |

| Kersten et al., 2015, Norway [41] | Retrospective study | Medication review | Investigated the clinical impact of PIMs in acutely hospitalised older adults. | Anticholinergic prescriptions were reduced from 39.2% to 37.9% |

| Juola et al., 2015, Finland [40] | Cluster RCT | Educational intervention | Nursing staff working in the intervention wards received two 4-h interactive training sessions based on constructive learning theory to recognise harmful medications and adverse drug events. | No significant differences in the change in prevalence of anticholinergic drugs. |

| Kersten et al., 2013, Norway [21] | RCT | Multidisciplinary drug review | Single Blind MDRD was conducted that recruited long-term nursing home residents with a total ADS score of greater than or equal to 3 | After 8 weeks, the median ADS score was significantly reduced from 4 to 2 in the intervention group. The largest improvement in immediate recall after 8 weeks was observed in the five patients in the intervention group who had their ADS score reduced to 0 |

| Ghibelli et al., 2013, Italy [48] | Pre, post-intervention study | INTERcheck CPSS | INTERcheck is a CPSS developed to optimise drug prescription for older people with multimorbidity and minimise the occurrence of adverse drug reactions. | The use of INTERCheck was associated with a significant reduction in PIMs and new-onset potentially severe DDIs. |

| Yeh et al., 2013, Taiwan [49] | Prospective case-control study | Educational program for primary care physicians | Educational program for primary care physicians serving in Veterans’ Homes, focusing on anticholinergic adverse reactions in geriatrics and the CR-ACHS | CR-ACHS was significantly reduced in the intervention group at 12-week follow-up. |

| Boustani et al., 2012, USA [36] | RCT | CDSS Alert (anticholinergic discontinuation) | CDSS alert system sends an interruptive alert if any of the 18 anticholinergics were prescribed, recommending stopping the drug, suggesting an alternative, or recommending dose modification. | Physicians receiving the CDSS issued more discontinuation orders of definite anticholinergics, but the results were not statistically significant. Results suggest that human interaction may play an important role in accepting recommendations aimed at improving the care of hospitalised older adults with CI. |

| Gnjidic et al., 2010, Australia [23] | Cluster RCT | Medication review | The study intervention included a letter and phone call to GPs, using DBI to prompt them to consider dose reduction or cessation of anticholinergic and sedative medications. | At follow-up, a DBI change was observed in 16 participants. DBI decreased in 12 participants, 6 (19%) in the control group, and 6 (32%) in the intervention group. |

| Castelino et al., 2010, Australia [22] | Retrospective study | Medication reviews by pharmacist | HMR by pharmacists for leads to an improvement in the use of medications | DBI and PIMs identified in 60.5% and 39.8% of the patients. Significant reduction in the cumulative DBI scores for all patients was observed following pharmacists’ recommendations |

| Starner et al., 2009, USA [33] | Retrospective study | Educational Intervention | Intervention letters were mailed to the physicians for patients having ≥1 DAE claim | Noticeable decrease was observed after a 6-month follow-up of the intervention in the reduction of DAE claims (48.8%) specifically reduction of anticholinergics (66.7%) was highest |

| Nishtala et al., 2009, Australia [37] | Retrospective study | RMMR | Clinical Pharmacist-led medication review decreased the DBI in older people | GP’s uptake of recommendations made by pharmacists resulted in a decrease in DBI score. Clinical pharmacist-conducted medication reviews can reduce prescribing of anticholinergic drugs and significantly decrease the DBI score of the study population. |

| van Eijk et al., 2001, Netherlands [50] | RCT | Educational visits as an individual and a group for general practitioners and pharmacists |

Educational visits used academic detailing to discuss prescribing of highly anticholinergic antidepressants in elderly people. | The rate of starting anticholinergic antidepressants in the elderly reduced 26% (in the individual intervention) and 45% (in the group intervention) The use of less anticholinergic antidepressants increased by 40% and 29%, respectively |

MAI, medication appropriateness index; GPs, general practitioners; DBI, drug burden index; NPI, neuropsychiatry inventory; RCT, randomised controlled trial; CDSS, clinical decision support system alert; DAE, drugs to be avoided in the elderly; DRPs, drug-related problems; CI, cognitive impairment; ACB, anticholinergic burden; MDRD, modification of diet in renal disease study equation; ADS, anticholinergic drug scale; PIMs, potentially inappropriate medications; CPSS, computerised prescription support system; DDIs, drug–drug interactions; EHR, electronic health record; DHS, Department of Health Services; ARS, anticholinergic risk scale; CR-ACHS, clinician-rated anticholinergic score; HMR, home medicines review; IA-ADAPT, improving antipsychotic appropriateness in dementia patients; CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Partnership to Improve Dementia Care; BPSD, Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia; RMMRs, Residential Medication Management Reviews; ACM, anticholinergic medication.

Table 2. The quantitative summary of included studies.

| Author, Year, Country |

Study Design | Setting | Sample Size | Mean Age (Years) | Gender (Female %) | Study Duration | Follow-Up | Relevant Outcome(s) |

Outcome Measure | Significant Association (±) |

Statistical Tests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control/Pre | Intervention/Post | |||||||||||

| Riordan et al., 2019, Ireland [42] | Convergent parallel mixed-methods design (before and after) | General Practice | 154 | 75.0 | 72.1 | 5 months | 6 months | Effects on DBI and ACB scores | Patients having an ACB score of 0 (34%) | Patients having an ACB score of 0 (31%) 65% of patients did not show any change in DBI over time |

− | SD, Range, IQR, Frequency, Percentages |

| Ailabouni et al., 2019, New Zealand [43] | A single group (pre- and post-comparison) feasibility study | Residential care facilities | 46 | 65.0 | 74.0 | 6 months | 2 weeks | Reduction in DBI score | ≥0.5 (median DBI) | 0.34 (median DBI) | + | Wilcox-signed Rank test (WSR) t-test Fisher’s exact test |

| Toivo et al., 2019, Belgium [44] | Cluster RCT | Primary care | 129 | 82.8 | 69.8 | 1 year | 1 year | Anticholinergic use | 18.8% (Anticholinergic use at baseline) 18.8% (Anticholinergic use at 12 months) |

29.6% (Anticholinergic use at baseline) 18.5% (Anticholinergic use at 12 months) |

− | Binary logistic regression, two-sided statistical tests |

| Hernandez et al., 2020, Spain [45] | Prospective pre- and post-interventional study | Intermediate care hospital | 55 | 84.6 | 60.0 | 12 months | NA | Anticholinergic burden per Drug Burden Index (DBI) | 1.38 ± 0.7 (Mean DBI) |

1.08 ± 0.7 (Mean DBI) |

+ | Kolmogorov–Smirnov test Student’s t-test |

| Lenander et al., 2018, Sweden [46] | Cross-sectional | Primary care | 1720 | 87.5 | 74.5 | 1 year | 8 weeks | Discontinuation of DRPs | Pts with anticholinergics = 9.2% | Pts with anticholinergics = 4.2% | + | Student’s t-test, Chi-square |

| Weichert et al., 2018, Finland [39] | Observational study | Hospital | 549 | 79.6 | 58.3 | 1 year, 5 months | 30 days | Reduction in ACB Score during the hospital stay | Patients on DAPs on admission = 60.8% | Patients on DAPs on discharge = 57.7 | − | Shapiro–Wilk test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test,2 sample t-test, Yates and Pearson’s chi-square test multivariate binary logistic regression |

| Lenander et al., 2017 Sweden [30] | Interventional pilot study | Primary care | 2400 to 13,700 patients (estimated) | 65–79 (range) | 63 | 9 months | 6 months | Reduction in anticholinergic PIMs (before/after) | Anticholinergic prescriptions before intervention (4513) | Anticholinergic prescriptions after intervention (3824) | + | Chi-square test |

| Moga et al., 2017, USA [29] | Parallel arm Randomised Interventional study | Alzheimer’s Disease Center | 49 | 77.7 ± 6.6 | 70.0 | 1 year | 8 weeks | Significant reduction in anticholinergic drug scale (ADS) Score | 1.0 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.3) | + | Student’s t-tests (or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for non-normally distributed variables), Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests |

| Lagrange et al., 2017, France [47] | Retrospective study | Hospital | 187 | 73.9 | 63.1 | 10.5 months | 33 and 37 days | Change in number of prescriptions | 6538 doses (Anticholinergics) |

4696 doses (Anticholinergics) |

+ | Descriptive statistics |

| Carnahan et al., 2017, USA [34] | Quasi-experimental study design | Nursing home | 411 | 86.7 | 77.0 | 1 year 9 months | 276 days | Anticholinergic use | Mean (SD) 35.9% (12.0%) |

Mean (SD) 36.1% (10.9%) |

− | Generalised linear mixed logistic regression |

| Antipsychotic use | Mean (SD) 17.7% (10.4%) |

Mean (SD) 20.7% (10.6%) |

+ | |||||||||

| Hanus et al., 2016, USA [35] | Observational Pilot study | Medical clinics | 59 | 77 ± 9.3 | 51.0 | 2 months | 2 weeks | Reduction in ACB Score, Increased medication acceptance rate |

1.08 50% |

0.89 95% |

+ | Generalised linear mixed-effects model, paired t-test |

| McLarin et al., 2016, Australia [38] | Retrospective study. | Aged care facilities | 814 | 85.6 | 69.6 | NA | NA | Reduction in anticholinergic medications after a medication review | Mean (SD) 3.73 (1.46) |

Mean (SD) 3.32 (1.7) |

+ | Wilcoxon signed-rank test, ANOVA |

| Kersten et al., 2015, Norway [41] | Retrospective study | Hospital | 232 | 86.1 | 59.1 | 8 months | 1 year | Reduction in anticholinergic prescriptions | Prevalence of anticholinergic drugs was significantly reduced (p < 0.02) | + | Paired samples Student’s t-test, McNamar’s test, Mann–Whitney U tests, ANOVA, linear regression | |

| Juola et al., 2015, Finland [40] | Cluster RCT | Assisted living facilities | 227 | 83.0 | 70.9 | 1 year | 1 year | Mean Anticholinergic drugs | 1.0 (Mean Anticholinergic drugs) |

1.2 (Mean Anticholinergic drugs) |

− | t-tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, or Chi-square tests, GEE models, Poisson regression models |

| Kersten et al., 2013, Norway [21] | RCT | Nursing home | 87 | 85.0 | 39.0 | 8 weeks | 8 weeks | Marked reduction in ADS score | Median = 4 | Median = 2 | + | ANCOVA, Poisson regression analysis |

| Ghibelli et al., 2013, Italy [48] | Pre- and post-intervention study | Hospital | 75 for Pre 75 for Post |

81 | 58.3 | 4 months | NA | Reduction in ACB score | 1.3 | 1.1 | − | Pearson Chi-square test, Student’s t-test |

| Yeh et al., 2013, Taiwan [49] | Prospective case-control | Veteran Home | 67 | 83.4 | NA | 12 weeks | 12 weeks | Anticholinergic Burden (CR-ACHS) | 1.0 ± 1.1 (Mean CR-ACHS) |

−0.5 ± 1.1 (Mean CR-ACHS) |

+ | Wilcoxon signed ranks test |

| Boustani et al.,2012, USA [36] | RCT | Hospital | 424 | 74.8 | 68.0 | 21 months | At the time of discharge | Discontinuation of AC prescriptions | anticholinergic discontinued = 31.2% | anticholinergic discontinued = 48.9% | _ | Fisher’s exact test, t-test, logistic regression, multiple regression |

| Gnjidic et al., 2010, Australia [23] | Cluster RCT | Self-care retirement village | 115 | 84.3 | 73.0 | 13 months | 3 months | Drug Burden Index (DBI) | 0.26 ± 0.34 (mean DBI) | 0.22 ± 0.42 (mean DBI) | − | Kolmogorov–Smirnov test Mann–Whitney nonparametric test X2 test |

| Castelino et al., 2010, Australia [22] | A retrospective analysis of medication reviews | Community-dwelling | 372 | 76.1 | 55.0 | NA | NA | Impact of pharmacist’s on DBI scores | Sum of DBI scores = 206.86 | Sum of DBI scores = 157.26 | + | Wilcoxon signed-rank test |

| Starner et al., 2009, USA [33] | Retrospective study | Pharmacy claims data | 10,364 | 65.0 | NA | 8 months | 6 months | Rate of discontinued anticholinergics | NA | 66.7% | + | NA |

| Nishtala et al., 2009, Australia [37] | Retrospective study | Aged care homes | 500 | 84.0 | 75.0 | 6 months | 2 months | Significant decrease in DBI score | NA | 12% decrease in DBI | + | 2-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test |

| van Eijk et al., 2001, Netherlands [50] | RCT | Primary care | 46,078 | 71 | 58.0 | 1 year | NA | Reduction in the prescribing of anticholinergics | 30% reduction in the rate of starting highly anticholinergic antidepressant in the individual intervention arms compared with the control arm | 40% reduction in the rate of starting highly anticholinergic antidepressants in the group intervention arms compared with the control arm | + | Poisson regression model |

RCT, randomised controlled trial; DBI, drug burden index; DRPs, drug-related problems; ACB, anticholinergic burden; PIM, potentially inappropriate medications; WSR, Wilcox-signed rank test; SD, standard deviation; GPs, general practitioner; CR-ACHS, clinician-rated anticholinergic score; and NA, not available.

2.2. Methodological Quality of Studies

2.2. Methodological Quality of Studies

All eligible studies were rated for their methodological quality, and many studies (n = 14, 61%) were identified to be of good quality based on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale [22][30][33][34][37][38][39][41][42][43][45][46][47][48][22,30,38,39,42,43,44,46,47,48,50,51,52,53] (Table S2). The quality of the RCTs was critically appraised using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool as shown in Supplementary Table S3. There was a general lack of adequate blinding between study subjects and healthcare practitioners, and between outcomes and assessors. Nonetheless, the follow-up duration was either not clearly specified or insufficient (less than six months) in many studies [21][22][23][29][35][36][37][38][39][43][45][46][47][48][49][50][21,22,23,29,40,41,42,43,44,48,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Altogether, the studies had a duration of follow-up ranging from 14 days [35][43][40,48] to 1 year [40][41][44][45,46,49] (Table 2).

2.3. Intervention Characteristics

All studies tested single-component interventions, and medication review was the most common single-component healthcare practitioner-oriented intervention [21][22][23][37][38][39][41][43][45][46][49][21,22,23,42,43,44,46,48,50,51,54] followed by the provision of education to the healthcare practitioners [33][34][40][42][49][50][38,39,45,47,54,55]. Healthcare practitioners conducted medication reviews using patient notes or tools such as drug burden index (DBI) and anticholinergic burden (ACB) [23][37][38][39][43][45][23,42,43,44,48,50]. Pharmacists implemented interventions without collaboration with other healthcare practitioners in nearly half of the studies (n = 11).

Healthcare practitioner-initiated education mainly consisted of professional components, such as academic detailing sessions for physicians [42][49][50][47,54,55], evidence-based training programs to improve dispensing [34][39], interactive training sessions for nurses [40][45], and mailing of intervention letters to the physicians [33][38]. In three studies [21][29][30][21,29,30], healthcare practitioners also performed interventions such as targeted patient-centred, pharmacist–physician team medication therapy management (MTM) intervention, SÄKLÄK project, and multidisciplinary medication review in collaborations with other healthcare practitioners. A context-aware pharmaceutical analysis tool was tested in France to automatically compare prescriptions recorded in computerised patient files against the main consensual guidelines [47][52]. Another study tested the clinical decision support system to discontinue orders of definite anticholinergic medications for hospitalised patients with cognitive impairment [36][41]. Similarly, a study tested targeted patient-centred pharmacist–physician team MTM intervention to reduce the consumption of inappropriate anticholinergic medications in older patients [29]. In Italy, researchers tested the INTERcheck computerised prescription support system to optimise drug prescriptions and minimise the occurrence of adverse drug reactions [48][53].

2.4. Effectiveness of Interventions at Improving Anticholinergic Prescribing Practice

Sixteen studies (70%) [21][22][29][30][33][34][35][37][38][41][43][45][46][47][49][50][21,22,29,30,38,39,40,42,43,46,48,50,51,52,54,55] investigating a healthcare practitioner-oriented intervention reported a significant reduction in anticholinergic prescribing errors, whereas seven studies (30%) [23][36][39][40][42][44][48][23,41,44,45,47,49,53] reported no significant effect (Table 2). Similarly, medication review (n = 8) and the provision of education (n = 4) were the most common interventions in these sixteen studies; however, these studies varied in their designs. There were 14 studies (87.5%) [22][30][33][34][37][38][39][41][42][43][45][46][47][48][22,30,38,39,42,43,44,46,47,48,50,51,52,53] that were of high quality, and of those, 11 studies [22][30][33][34][37][38][41][43][45][46][47][22,30,38,39,42,43,46,48,50,51,52] showed a significant reduction in anticholinergic prescribing errors. Seven studies had a follow-up period of ≥6 months, and four studies showed a significant reduction in anticholinergic prescribing errors. With a shorter follow-up period of 2 weeks to 6 months, 4 studies [37][43][46][47][42,48,51,52] out of 10 studies reported reductions in anticholinergic prescribing errors (Table 2).

Healthcare practitioner-oriented interventions that reported a significant reduction in anticholinergic prescribing errors included: medication review, education provision to healthcare practitioners, pharmacist-led electronic health record-based population health initiative and anticholinergic risk scale service, targeted patient-centred, pharmacist–physician team MTM intervention, context-aware pharmaceutical analysis tool, and SÄKLÄK project. Healthcare practitioner-oriented interventions were most effective in reducing ACB [21][29][35][49][21,29,40,54], DBI [22][37][43][45][22,42,48,50], and discontinuation or reduction of anticholinergic medications [30][33][34][38][41][46][47][50][30,38,39,43,46,51,52,55]. Hernandez et al. 2020 reported a decline in DBI from 1.38 (control group) to 1.08 (intervention group) [45][50]. Another study reported a reduction in ACB score from 1.08 (control group) to 0.89 (intervention group) [35][40]. A retrospective study by McLarin et al. [38][43] in Australia found a reduction in the mean scores of anticholinergic medications from 3.73 to 3.02 after implementing medication review.