Anti-neuroinflammatory treatment has gained importance in the search for pharmacological treatments of different neurological and psychiatric diseases, such as depression, schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical studies demonstrate a reduction of the mentioned diseases’ symptoms after administration of anti-inflammatory drugs. Coumarin derivates have been shown to elicit anti-neuroinflammatory effects via G-protein coupled receptor (GPR)55, with possibly reduced side-effects compared to the known anti-inflammatory drugs. In this study, we therefore evaluated the anti-inflammatory capacities of the two novel coumarin-based compounds, KIT C and KIT H, in human neuroblastoma cells and primary murine microglia. Both compounds reduced PGE2-concentrations likely via inhibition of COX-2 synthesis in SK-N-SH cells but only KIT C decreased PGE2-levels in primary microglia. Examination of other pro- and anti-inflammatory parameters showed varying effects of both compounds. Therefore, the differences in the effects of KIT C and KIT H might be explained by functional selectivity as well as tissue- or cell-dependent expression and signal pathways coupled to GPR55. Understanding the role of chemical residues in functional selectivity and specific cell- and tissue-targeting might open new therapeutic options in pharmacological drug development and might improve the treatment of the mentioned diseases intervening in an early step of their pathogenesis.

Anti-neuroinflammatory treatment has gained importance in the search for pharmacological treatments of different neurological and psychiatric diseases, such as depression, schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical studies demonstrate a reduction of the mentioned diseases’ symptoms after administration of anti-inflammatory drugs. Coumarin derivates have been shown to elicit anti-neuroinflammatory effects via G-protein coupled receptor (GPR)55, with possibly reduced side-effects compared to the known anti-inflammatory drugs.

- neuroinflammation

- GPR55

- coumarin derivates

- PGE2

- functional selectivity

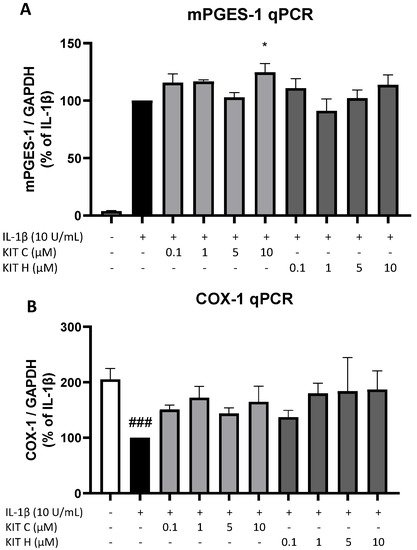

1. Introduction

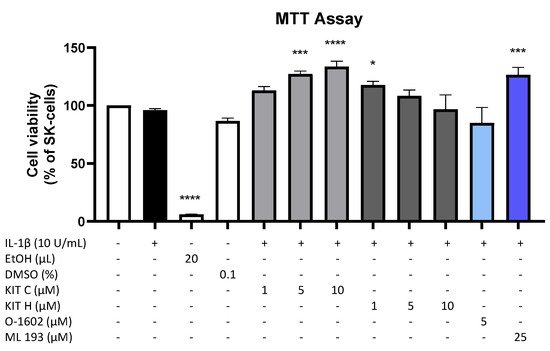

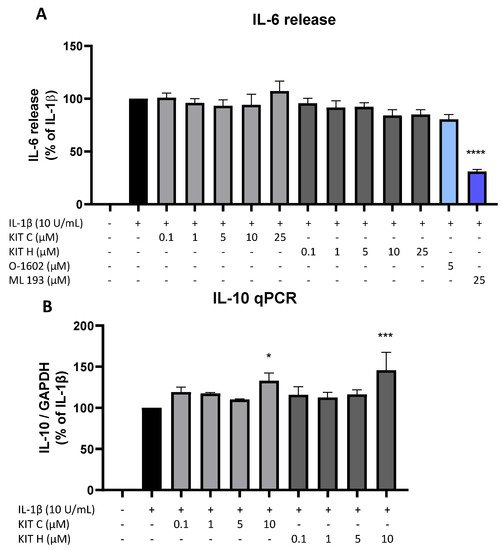

2. Effects of the Compounds on Cell Viability

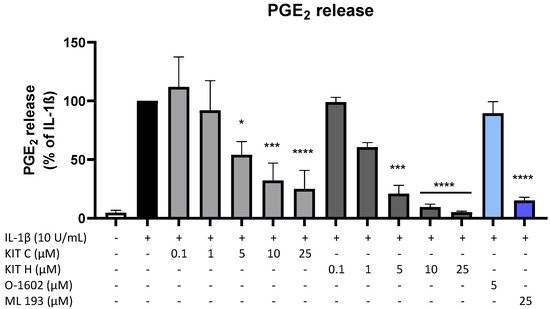

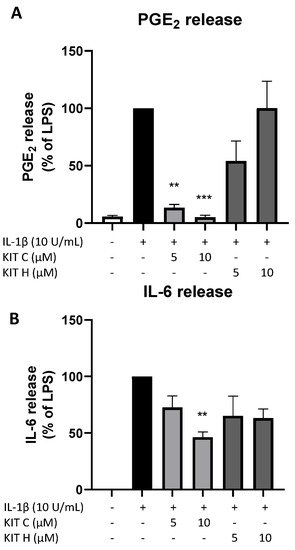

3. Effects of the Compounds on IL-1β-Induced PGE2-Release

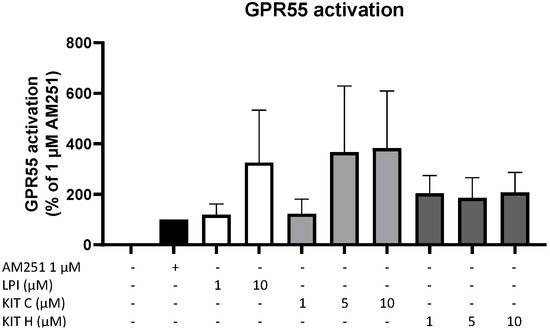

4. GPR55 Activity of KIT C and KIT H

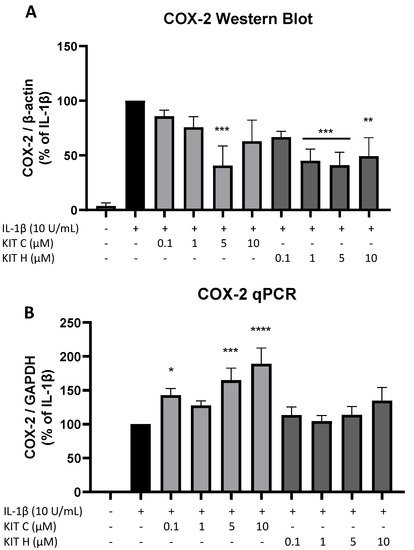

5. Effects of KIT C and KIT H on COX-2 mRNA and Protein Levels

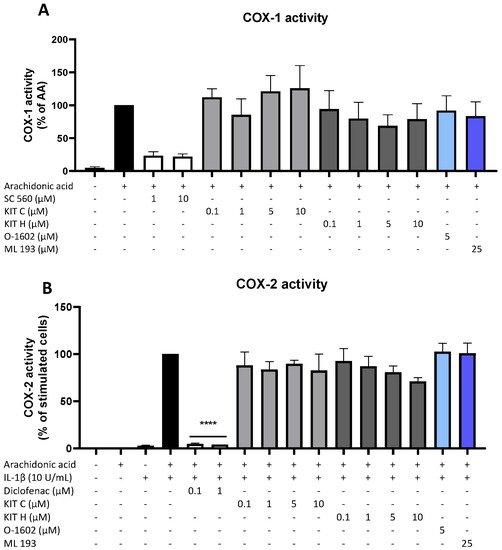

6. Effects of KIT C and KIT H on COX-Activity

7. Effects of KIT C and KIT H on COX-1 and mPGES-1 Expression

8. Effects of KIT C and KIT H on IL-1β–Induced Cytokine Release

9. Effects of KIT C and KIT H on PGE2- and IL-6 Release in LPS-Stimulated Primary Mouse Microglia

References

- Craft, J.M.; Watterson, D.M.; Van Eldik, L.J. Neuroinflammation: A Potential Therapeutic Target. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 2005, 9, 887–900, doi:10.1517/14728222.9.5.887.

- Troubat, R.; Barone, P.; Leman, S.; Desmidt, T.; Cressant, A.; Atanasova, B.; Brizard, B.; El Hage, W.; Surget, A.; Belzung, C.; et al. Neuroinflammation and Depression: A Review. Eur J Neurosci 2021, 53, 151–171, doi:10.1111/ejn.14720.

- Picca, A.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Landi, F.; Bernabei, R.; Marzetti, E. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Neuroinflammation: Intertwined Roads to Neurodegeneration. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 647, doi:10.3390/antiox9080647.

- Najjar, S.; Pearlman, D.M.; Alper, K.; Najjar, A.; Devinsky, O. Neuroinflammation and Psychiatric Illness. J Neuroinflammation 2013, 10, 816, doi:10.1186/1742-2094-10-43.

- Köhler‐Forsberg, O.; N. Lydholm, C.; Hjorthøj, C.; Nordentoft, M.; Mors, O.; Benros, M.E. Efficacy of Anti‐inflammatory Treatment on Major Depressive Disorder or Depressive Symptoms: Meta‐analysis of Clinical Trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2019, 139, 404–419, doi:10.1111/acps.13016.

- Rivers-Auty, J.; Mather, A.E.; Peters, R.; Lawrence, C.B.; Brough, D. Anti-Inflammatories in Alzheimer’s Disease—Potential Therapy or Spurious Correlate? Brain Communications 2020, 2, fcaa109, doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcaa109.

- Esposito, E.; Di Matteo, V.; Benigno, A.; Pierucci, M.; Crescimanno, G.; Di Giovanni, G. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Parkinson’s Disease. Experimental Neurology 2007, 205, 295–312, doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.02.008.

- Davis, A.; Robson, J. The Dangers of NSAIDs: Look Both Ways. Br J Gen Pract 2016, 66, 172–173, doi:10.3399/bjgp16X684433.

- Choi, G.E.; Han, H.J. Glucocorticoid Impairs Mitochondrial Quality Control in Neurons. Neurobiology of Disease 2021, 152, 105301, doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2021.105301.

- Sanz-Blasco, S.; Valero, R.A.; Rodríguez-Crespo, I.; Villalobos, C.; Núñez, L. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Overload Underlies Aβ Oligomers Neurotoxicity Providing an Unexpected Mechanism of Neuroprotection by NSAIDs. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2718, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002718.

- Lee, H.; Trott, J.S.; Haque, S.; McCormick, S.; Chiorazzi, N.; Mongini, P.K.A. A Cyclooxygenase-2/Prostaglandin E Pathway Augments Activation-Induced Cytosine Deaminase Expression within Replicating Human B Cells. J.I. 2010, 185, 5300–5314, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1000574.

- Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; MacDowell, K.S.; García-Bueno, B.; Cabrera, B.; González-Pinto, A.; Saiz, P.; Lobo, A.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R.; Berrocoso, E.; et al. Differences in the Regulation of Inflammatory Pathways in Adolescent- and Adult-Onset First-Episode Psychosis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019, 28, 1395–1405, doi:10.1007/s00787-019-01295-8.

- Saliba, S.W.; Jauch, H.; Gargouri, B.; Keil, A.; Hurrle, T.; Volz, N.; Mohr, F.; van der Stelt, M.; Bräse, S.; Fiebich, B.L. Anti-Neuroinflammatory Effects of GPR55 Antagonists in LPS-Activated Primary Microglial Cells. J Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 322, doi:10.1186/s12974-018-1362-7.

- Saliba, S.W.; Gläser, F.; Deckers, A.; Keil, A.; Hurrle, T.; Apweiler, M.; Ferver, F.; Volz, N.; Endres, D.; Bräse, S.; et al. Effects of a Novel GPR55 Antagonist on the Arachidonic Acid Cascade in LPS-Activated Primary Microglial Cells. IJMS 2021, 22, 2503, doi:10.3390/ijms22052503.

- Liu, Q.; Liang, X.; Wang, Q.; Wilson, E.N.; Lam, R.; Wang, J.; Kong, W.; Tsai, C.; Pan, T.; Larkin, P.B.; et al. PGE Signaling via the Neuronal EP2 Receptor Increases Injury in a Model of Cerebral Ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019, 116, 10019–10024, doi:10.1073/pnas.1818544116.

- Rempel, V.; Volz, N.; Gläser, F.; Nieger, M.; Bräse, S.; Müller, C.E. Antagonists for the Orphan G-Protein-Coupled Receptor GPR55 Based on a Coumarin Scaffold. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 4798–4810, doi:10.1021/jm4005175.

- Apweiler, M.; Saliba, S.W.; Streyczek, J.; Hurrle, T.; Gräßle, S.; Bräse, S.; Fiebich, B.L. Targeting Oxidative Stress: Novel Coumarin-Based Inverse Agonists of GPR55. IJMS 2021, 22, 11665, doi:10.3390/ijms222111665.

- Sawzdargo, M.; Nguyen, T.; Lee, D.K.; Lynch, K.R.; Cheng, R.; Heng, H.H.Q.; George, S.R.; O’Dowd, B.F. Identification and Cloning of Three Novel Human G Protein-Coupled Receptor Genes GPR52, ΨGPR53 and GPR55: GPR55 Is Extensively Expressed in Human Brain. Molecular Brain Research 1999, 64, 193–198, doi:10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00277-0.

- Shore, D.M.; Reggio, P.H. The Therapeutic Potential of Orphan GPCRs, GPR35 and GPR55. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, doi:10.3389/fphar.2015.00069.

- Oka, S.; Nakajima, K.; Yamashita, A.; Kishimoto, S.; Sugiura, T. Identification of GPR55 as a Lysophosphatidylinositol Receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007, 362, 928–934, doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.078.

- Rempel, V.; Volz, N.; Hinz, S.; Karcz, T.; Meliciani, I.; Nieger, M.; Wenzel, W.; Bräse, S.; Müller, C.E. 7-Alkyl-3-Benzylcoumarins: A Versatile Scaffold for the Development of Potent and Selective Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists and Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7967–7977, doi:10.1021/jm3008213.

- Falasca, M.; Ferro, R. Role of the Lysophosphatidylinositol/GPR55 Axis in Cancer. Advances in Biological Regulation 2016, 60, 88–93, doi:10.1016/j.jbior.2015.10.003.

- Moreno-Navarrete, J.M.; Catalan, V.; Whyte, L.; Diaz-Arteaga, A.; Vazquez-Martinez, R.; Rotellar, F.; Guzman, R.; Gomez-Ambrosi, J.; Pulido, M.R.; Russell, W.R.; et al. The L- -Lysophosphatidylinositol/GPR55 System and Its Potential Role in Human Obesity. Diabetes 2012, 61, 281–291, doi:10.2337/db11-0649.

- Whyte, L.S.; Ryberg, E.; Sims, N.A.; Ridge, S.A.; Mackie, K.; Greasley, P.J.; Ross, R.A.; Rogers, M.J. The Putative Cannabinoid Receptor GPR55 Affects Osteoclast Function in Vitro and Bone Mass in Vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 16511–16516, doi:10.1073/pnas.0902743106.

- Medina-Vera, D.; Rosell-Valle, C.; López-Gambero, A.J.; Navarro, J.A.; Zambrana-Infantes, E.N.; Rivera, P.; Santín, L.J.; Suarez, J.; Rodríguez de Fonseca, F. Imbalance of Endocannabinoid/Lysophosphatidylinositol Receptors Marks the Severity of Alzheimer’s Disease in a Preclinical Model: A Therapeutic Opportunity. Biology 2020, 9, 377, doi:10.3390/biology9110377.

- Celorrio, M.; Rojo-Bustamante, E.; Fernández-Suárez, D.; Sáez, E.; Estella-Hermoso de Mendoza, A.; Müller, C.E.; Ramírez, M.J.; Oyarzábal, J.; Franco, R.; Aymerich, M.S. GPR55: A Therapeutic Target for Parkinson’s Disease? Neuropharmacology 2017, 125, 319–332, doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.08.017.

- Fatemi, I.; Abdollahi, A.; Shamsizadeh, A.; Allahtavakoli, M.; Roohbakhsh, A. The Effect of Intra-Striatal Administration of GPR55 Agonist (LPI) and Antagonist (ML193) on Sensorimotor and Motor Functions in a Parkinson’s Disease Rat Model. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2021, 33, 15–21, doi:10.1017/neu.2020.30.

- Hill, J.D.; Zuluaga-Ramirez, V.; Gajghate, S.; Winfield, M.; Sriram, U.; Rom, S.; Persidsky, Y. Activation of GPR55 Induces Neuroprotection of Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Immune Responses of Neural Stem Cells Following Chronic, Systemic Inflammation. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2019, 76, 165–181, doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2018.11.017.

- Rahimi, A.; Hajizadeh Moghaddam, A.; Roohbakhsh, A. Central Administration of GPR55 Receptor Agonist and Antagonist Modulates Anxiety-Related Behaviors in Rats. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2015, 29, 185–190, doi:10.1111/fcp.12099.

- Wróbel, A.; Serefko, A.; Szopa, A.; Ulrich, D.; Poleszak, E.; Rechberger, T. O-1602, an Agonist of Atypical Cannabinoid Receptors GPR55, Reverses the Symptoms of Depression and Detrusor Overactivity in Rats Subjected to Corticosterone Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1002, doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.01002.

- Staton, P.C.; Hatcher, J.P.; Walker, D.J.; Morrison, A.D.; Shapland, E.M.; Hughes, J.P.; Chong, E.; Mander, P.K.; Green, P.J.; Billinton, A.; et al. The Putative Cannabinoid Receptor GPR55 Plays a Role in Mechanical Hyperalgesia Associated with Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain. Pain 2008, 139, 225–236, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.006.

- García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Navarrete, F.; Navarro, G.; Reyes-Resina, I.; Franco, R.; Lanciego, J.L.; Giner, S.; Manzanares, J. Alterations in Gene and Protein Expression of Cannabinoid CB2 and GPR55 Receptors in the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex of Suicide Victims. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 796–806, doi:10.1007/s13311-018-0610-y.

- Ishiguro, H.; Onaivi, E.S.; Horiuchi, Y.; Imai, K.; Komaki, G.; Ishikawa, T.; Suzuki, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Ando, T.; Higuchi, S.; et al. Functional Polymorphism in the GPR55 Gene Is Associated with Anorexia Nervosa. Synapse 2011, 65, 103–108, doi:10.1002/syn.20821.

- Ryberg, E.; Larsson, N.; Sjögren, S.; Hjorth, S.; Hermansson, N.-O.; Leonova, J.; Elebring, T.; Nilsson, K.; Drmota, T.; Greasley, P.J. The Orphan Receptor GPR55 Is a Novel Cannabinoid Receptor: GPR55, a Novel Cannabinoid Receptor. British Journal of Pharmacology 2007, 152, 1092–1101, doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707460.

- Lauckner, J.E.; Jensen, J.B.; Chen, H.-Y.; Lu, H.-C.; Hille, B.; Mackie, K. GPR55 Is a Cannabinoid Receptor That Increases Intracellular Calcium and Inhibits M Current. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 2699–2704, doi:10.1073/pnas.0711278105.

- Henstridge, C.M.; Balenga, N.A.; Schröder, R.; Kargl, J.K.; Platzer, W.; Martini, L.; Arthur, S.; Penman, J.; Whistler, J.L.; Kostenis, E.; et al. GPR55 Ligands Promote Receptor Coupling to Multiple Signalling Pathways. Br J Pharmacol 2010, 160, 604–614, doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00625.x.

- Kenakin, T. Functional Selectivity through Protean and Biased Agonism: Who Steers the Ship? Mol Pharmacol 2007, 72, 1393–1401, doi:10.1124/mol.107.040352.

- Kenakin, T.; Christopoulos, A. Signalling Bias in New Drug Discovery: Detection, Quantification and Therapeutic Impact. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013, 12, 205–216, doi:10.1038/nrd3954.

- Nørregaard, R.; Kwon, T.-H.; Frøkiær, J. Physiology and Pathophysiology of Cyclooxygenase-2 and Prostaglandin E2 in the Kidney. Kidney Research and Clinical Practice 2015, 34, 194–200, doi:10.1016/j.krcp.2015.10.004.

- Siljehav, V.; Olsson Hofstetter, A.; Jakobsson, P.-J.; Herlenius, E. MPGES-1 and Prostaglandin E2: Vital Role in Inflammation, Hypoxic Response, and Survival. Pediatr Res 2012, 72, 460–467, doi:10.1038/pr.2012.119.

- Olajide, O.A.; Velagapudi, R.; Okorji, U.P.; Sarker, S.D.; Fiebich, B.L. Picralima Nitida Seeds Suppress PGE2 Production by Interfering with Multiple Signalling Pathways in IL-1β-Stimulated SK-N-SH Neuronal Cells. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2014, 152, 377–383, doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.01.027.

- Apweiler, M.; Streyczek, J.; Saliba, S.W.; Ditrich, J.; Muñoz, E.; Fiebich, B.L. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidative Effects of AM404 in IL-1β-Stimulated SK-N-SH Neuroblastoma Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 789074, doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.789074.

- Candelario-Jalil, E.; Akundi, R.S.; Bhatia, H.S.; Lieb, K.; Appel, K.; Muñoz, E.; Hüll, M.; Fiebich, B.L. Ascorbic Acid Enhances the Inhibitory Effect of Aspirin on Neuronal Cyclooxygenase-2-Mediated Prostaglandin E2 Production. J Neuroimmunol 2006, 174, 39–51, doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.01.003.

- Akundi, R.S.; Candelario-Jalil, E.; Hess, S.; Hüll, M.; Lieb, K.; Gebicke-Haerter, P.J.; Fiebich, B.L. Signal Transduction Pathways Regulating Cyclooxygenase-2 in Lipopolysaccharide-Activated Primary Rat Microglia. Glia 2005, 51, 199–208, doi:10.1002/glia.20198.

- Medina, M.V.; D Agostino, A.; Ma, Q.; Eroles, P.; Cavallin, L.; Chiozzini, C.; Sapochnik, D.; Cymeryng, C.; Hyjek, E.; Cesarman, E.; et al. KSHV G-Protein Coupled Receptor VGPCR Oncogenic Signaling Upregulation of Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression Mediates Angiogenesis and Tumorigenesis in Kaposi’s Sarcoma. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, e1009006, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1009006.

- Pan, T.; Zhou, D.; Shi, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Liu, J.; Yang, Q.; Cao, L.; Zhang, J. Centromere Protein U (CENPU) Enhances Angiogenesis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Inhibiting Ubiquitin–Proteasomal Degradation of COX-2. Cancer Letters 2020, 482, 102–111, doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.003.

- Kenakin, T. The Classification of Seven Transmembrane Receptors in Recombinant Expression Systems. Pharmacol Rev 1996, 48, 413–463.

- Yap, J.K.Y.; Pickard, B.S.; Chan, E.W.L.; Gan, S.Y. The Role of Neuronal NLRP1 Inflammasome in Alzheimer’s Disease: Bringing Neurons into the Neuroinflammation Game. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56, 7741–7753, doi:10.1007/s12035-019-1638-7.

- Huang, Y.; Thathiah, A. Regulation of Neuronal Communication by G Protein-Coupled Receptors. FEBS Letters 2015, 589, 1607–1619, doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2015.05.007.

- Zhang, H.-Y.; Bi, G.-H.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Qu, H.; Zhang, S.-J.; Li, C.-Y.; Onaivi, E.S.; Gardner, E.L.; Xi, Z.-X.; et al. Species Differences in Cannabinoid Receptor 2 and Receptor Responses to Cocaine Self-Administration in Mice and Rats. Neuropsychopharmacol 2015, 40, 1037–1051, doi:10.1038/npp.2014.297.

- Dashti-Khavidaki, S.; Saidi, R.; Lu, H. Current Status of Glucocorticoid Usage in Solid Organ Transplantation. World J Transplant 2021, 11, 443–465, doi:10.5500/wjt.v11.i11.443.

- Saliba, S.W.; Marcotegui, A.R.; Fortwängler, E.; Ditrich, J.; Perazzo, J.C.; Muñoz, E.; de Oliveira, A.C.P.; Fiebich, B.L. AM404, Paracetamol Metabolite, Prevents Prostaglandin Synthesis in Activated Microglia by Inhibiting COX Activity. J Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 246, doi:10.1186/s12974-017-1014-3.

- Henstridge, C.M.; Balenga, N.A.B.; Ford, L.A.; Ross, R.A.; Waldhoer, M.; Irving, A.J. The GPR55 Ligand L‐α‐lysophosphatidylinositol Promotes RhoA‐dependent Ca 2+ Signaling and NFAT Activation. FASEB j. 2009, 23, 183–193, doi:10.1096/fj.08-108670.

- Fiebich, B.L.; Chrubasik, S. Effects of an Ethanolic Salix Extract on the Release of Selected Inflammatory Mediators in Vitro. Phytomedicine 2004, 11, 135–138, doi:10.1078/0944-7113-00338.

References

- Craft, J.M.; Watterson, D.M.; Van Eldik, L.J. Neuroinflammation: A potential therapeutic target. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2005, 9, 887–900.

- Troubat, R.; Barone, P.; Leman, S.; Desmidt, T.; Cressant, A.; Atanasova, B.; Brizard, B.; El Hage, W.; Surget, A.; Belzung, C.; et al. Neuroinflammation and depression: A review. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 151–171.

- Picca, A.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Landi, F.; Bernabei, R.; Marzetti, E. Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Neuroinflammation: Intertwined Roads to Neurodegeneration. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 647.

- Najjar, S.; Pearlman, D.M.; Alper, K.; Najjar, A.; Devinsky, O. Neuroinflammation and psychiatric illness. J. Neuroinflamm. 2013, 10, 816.

- Köhler-Forsberg, O.N.; Lydholm, C.; Hjorthøj, C.; Nordentoft, M.; Mors, O.; Benros, M.E. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatment on major depressive disorder or depressive symptoms: Meta-analysis of clinical trials. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019, 139, 404–419.

- Rivers-Auty, J.; Mather, A.E.; Peters, R.; Lawrence, C.B.; Brough, D. Anti-inflammatories in Alzheimer’s disease—Potential therapy or spurious correlate? Brain Commun. 2020, 2, fcaa109.

- Esposito, E.; Di Matteo, V.; Benigno, A.; Pierucci, M.; Crescimanno, G.; Di Giovanni, G. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 205, 295–312.

- Davis, A.; Robson, J. The dangers of NSAIDs: Look both ways. Br. J. Gen. Pract. J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, 172–173.

- Choi, G.E.; Han, H.J. Glucocorticoid impairs mitochondrial quality control in neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 152, 105301.

- Sanz-Blasco, S.; Valero, R.A.; Rodríguez-Crespo, I.; Villalobos, C.; Núñez, L. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Overload Underlies Aβ Oligomers Neurotoxicity Providing an Unexpected Mechanism of Neuroprotection by NSAIDs. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2718.

- Lee, H.; Trott, J.S.; Haque, S.; McCormick, S.; Chiorazzi, N.; Mongini, P.K.A. A Cyclooxygenase-2/Prostaglandin E Pathway Augments Activation-Induced Cytosine Deaminase Expression within Replicating Human B Cells. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 5300–5314.

- Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; MacDowell, K.S.; García-Bueno, B.; Cabrera, B.; González-Pinto, A.; Saiz, P.; Lobo, A.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R.; Berrocoso, E.; et al. Differences in the regulation of inflammatory pathways in adolescent- and adult-onset first-episode psychosis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 1395–1405.

- Saliba, S.W.; Jauch, H.; Gargouri, B.; Keil, A.; Hurrle, T.; Volz, N.; Mohr, F.; van der Stelt, M.; Bräse, S.; Fiebich, B.L. Anti-neuroinflammatory effects of GPR55 antagonists in LPS-activated primary microglial cells. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 322.

- Saliba, S.W.; Gläser, F.; Deckers, A.; Keil, A.; Hurrle, T.; Apweiler, M.; Ferver, F.; Volz, N.; Endres, D.; Bräse, S.; et al. Effects of a Novel GPR55 Antagonist on the Arachidonic Acid Cascade in LPS-Activated Primary Microglial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2503.

- Liu, Q.; Liang, X.; Wang, Q.; Wilson, E.N.; Lam, R.; Wang, J.; Kong, W.; Tsai, C.; Pan, T.; Larkin, P.B.; et al. PGE signaling via the neuronal EP2 receptor increases injury in a model of cerebral ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10019–10024.

- Rempel, V.; Volz, N.; Gläser, F.; Nieger, M.; Bräse, S.; Müller, C.E. Antagonists for the Orphan G-Protein-Coupled Receptor GPR55 Based on a Coumarin Scaffold. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 4798–4810.

- Apweiler, M.; Saliba, S.W.; Streyczek, J.; Hurrle, T.; Gräßle, S.; Bräse, S.; Fiebich, B.L. Targeting Oxidative Stress: Novel Coumarin-Based Inverse Agonists of GPR55. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11665.

- Sawzdargo, M.; Nguyen, T.; Lee, D.K.; Lynch, K.R.; Cheng, R.; Heng, H.H.Q.; George, S.R.; O’Dowd, B.F. Identification and cloning of three novel human G protein-coupled receptor genes GPR52, ΨGPR53 and GPR55: GPR55 is extensively expressed in human brain. Mol. Brain Res. 1999, 64, 193–198.

- Shore, D.M.; Reggio, P.H. The therapeutic potential of orphan GPCRs, GPR35 and GPR55. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 69.

- Oka, S.; Nakajima, K.; Yamashita, A.; Kishimoto, S.; Sugiura, T. Identification of GPR55 as a lysophosphatidylinositol receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 362, 928–934.

- Rempel, V.; Volz, N.; Hinz, S.; Karcz, T.; Meliciani, I.; Nieger, M.; Wenzel, W.; Bräse, S.; Müller, C.E. 7-Alkyl-3-benzylcoumarins: A Versatile Scaffold for the Development of Potent and Selective Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists and Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7967–7977.

- Falasca, M.; Ferro, R. Role of the lysophosphatidylinositol/GPR55 axis in cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2016, 60, 88–93.

- Moreno-Navarrete, J.M.; Catalan, V.; Whyte, L.; Diaz-Arteaga, A.; Vazquez-Martinez, R.; Rotellar, F.; Guzman, R.; Gomez-Ambrosi, J.; Pulido, M.R.; Russell, W.R.; et al. The L-α-Lysophosphatidylinositol/GPR55 System and Its Potential Role in Human Obesity. Diabetes 2012, 61, 281–291.

- Whyte, L.S.; Ryberg, E.; Sims, N.A.; Ridge, S.A.; Mackie, K.; Greasley, P.J.; Ross, R.A.; Rogers, M.J. The putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 affects osteoclast function in vitro and bone mass in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 16511–16516.

- Medina-Vera, D.; Rosell-Valle, C.; López-Gambero, A.J.; Navarro, J.A.; Zambrana-Infantes, E.N.; Rivera, P.; Santín, L.J.; Suarez, J.; Rodríguez de Fonseca, F. Imbalance of Endocannabinoid/Lysophosphatidylinositol Receptors Marks the Severity of Alzheimer’s Disease in a Preclinical Model: A Therapeutic Opportunity. Biology 2020, 9, 377.

- Celorrio, M.; Rojo-Bustamante, E.; Fernández-Suárez, D.; Sáez, E.; de Mendoza, A.E.-H.; Müller, C.E.; Ramírez, M.J.; Oyarzábal, J.; Franco, R.; Aymerich, M.S. GPR55: A therapeutic target for Parkinson’s disease? Neuropharmacology 2017, 125, 319–332.

- Fatemi, I.; Abdollahi, A.; Shamsizadeh, A.; Allahtavakoli, M.; Roohbakhsh, A. The effect of intra-striatal administration of GPR55 agonist (LPI) and antagonist (ML193) on sensorimotor and motor functions in a Parkinson’s disease rat model. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2021, 33, 15–21.

- Hill, J.D.; Zuluaga-Ramirez, V.; Gajghate, S.; Winfield, M.; Sriram, U.; Rom, S.; Persidsky, Y. Activation of GPR55 induces neuroprotection of hippocampal neurogenesis and immune responses of neural stem cells following chronic, systemic inflammation. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2019, 76, 165–181.

- Rahimi, A.; Hajizadeh Moghaddam, A.; Roohbakhsh, A. Central administration of GPR55 receptor agonist and antagonist modulates anxiety-related behaviors in rats. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 29, 185–190.

- Wróbel, A.; Serefko, A.; Szopa, A.; Ulrich, D.; Poleszak, E.; Rechberger, T. O-1602, an Agonist of Atypical Cannabinoid Receptors GPR55, Reverses the Symptoms of Depression and Detrusor Overactivity in Rats Subjected to Corticosterone Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1002.

- Staton, P.C.; Hatcher, J.P.; Walker, D.J.; Morrison, A.D.; Shapland, E.M.; Hughes, J.P.; Chong, E.; Mander, P.K.; Green, P.J.; Billinton, A.; et al. The putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 plays a role in mechanical hyperalgesia associated with inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Pain 2008, 139, 225–236.

- García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Navarrete, F.; Navarro, G.; Reyes-Resina, I.; Franco, R.; Lanciego, J.L.; Giner, S.; Manzanares, J. Alterations in Gene and Protein Expression of Cannabinoid CB2 and GPR55 Receptors in the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex of Suicide Victims. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 796–806.

- Ishiguro, H.; Onaivi, E.S.; Horiuchi, Y.; Imai, K.; Komaki, G.; Ishikawa, T.; Suzuki, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Ando, T.; Higuchi, S.; et al. Functional polymorphism in the GPR55 gene is associated with anorexia nervosa. Synapse 2011, 65, 103–108.

- Ryberg, E.; Larsson, N.; Sjögren, S.; Hjorth, S.; Hermansson, N.-O.; Leonova, J.; Elebring, T.; Nilsson, K.; Drmota, T.; Greasley, P.J. The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor: GPR55, a novel cannabinoid receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 152, 1092–1101.

- Lauckner, J.E.; Jensen, J.B.; Chen, H.-Y.; Lu, H.-C.; Hille, B.; Mackie, K. GPR55 is a cannabinoid receptor that increases intracellular calcium and inhibits M current. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2699–2704.

- Henstridge, C.M.; Balenga, N.A.; Schröder, R.; Kargl, J.K.; Platzer, W.; Martini, L.; Arthur, S.; Penman, J.; Whistler, J.L.; Kostenis, E.; et al. GPR55 ligands promote receptor coupling to multiple signalling pathways. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 160, 604–614.

- Kenakin, T. Functional Selectivity through Protean and Biased Agonism: Who Steers the Ship? Mol. Pharmacol. 2007, 72, 1393–1401.

- Kenakin, T.; Christopoulos, A. Signalling bias in new drug discovery: Detection, quantification and therapeutic impact. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 205–216.