SARS-CoV-2 is a coronavirus classified in the same subgroup as the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Both can cause a variety of respiratory illnesses ranging in severity from a common cold to severe pneumonia, inflammatory response, acute lung injury, and death. Research on COVID-19 revealed that SARS CoV-2 does not only affect the respiratory tract but can also lead to endothelial inflammation, cardiomyopathy, multi-organ dysfunction, neurological syndromes, and hypercoagulability. Progression of COVID-19 is rare in pregnant and postpartum women treated in the ICU. Preterm birth rate is high and COVID-19 requiring respiratory support increases the risk of poor maternal and neonatal outcome.

- maternal critical care

- COVID-19

- ARDS

- SARS-CoV-2

- pregnancy

- obstetrics

- severe COVID in pregnancy

1. Introduction

2. Current Insights

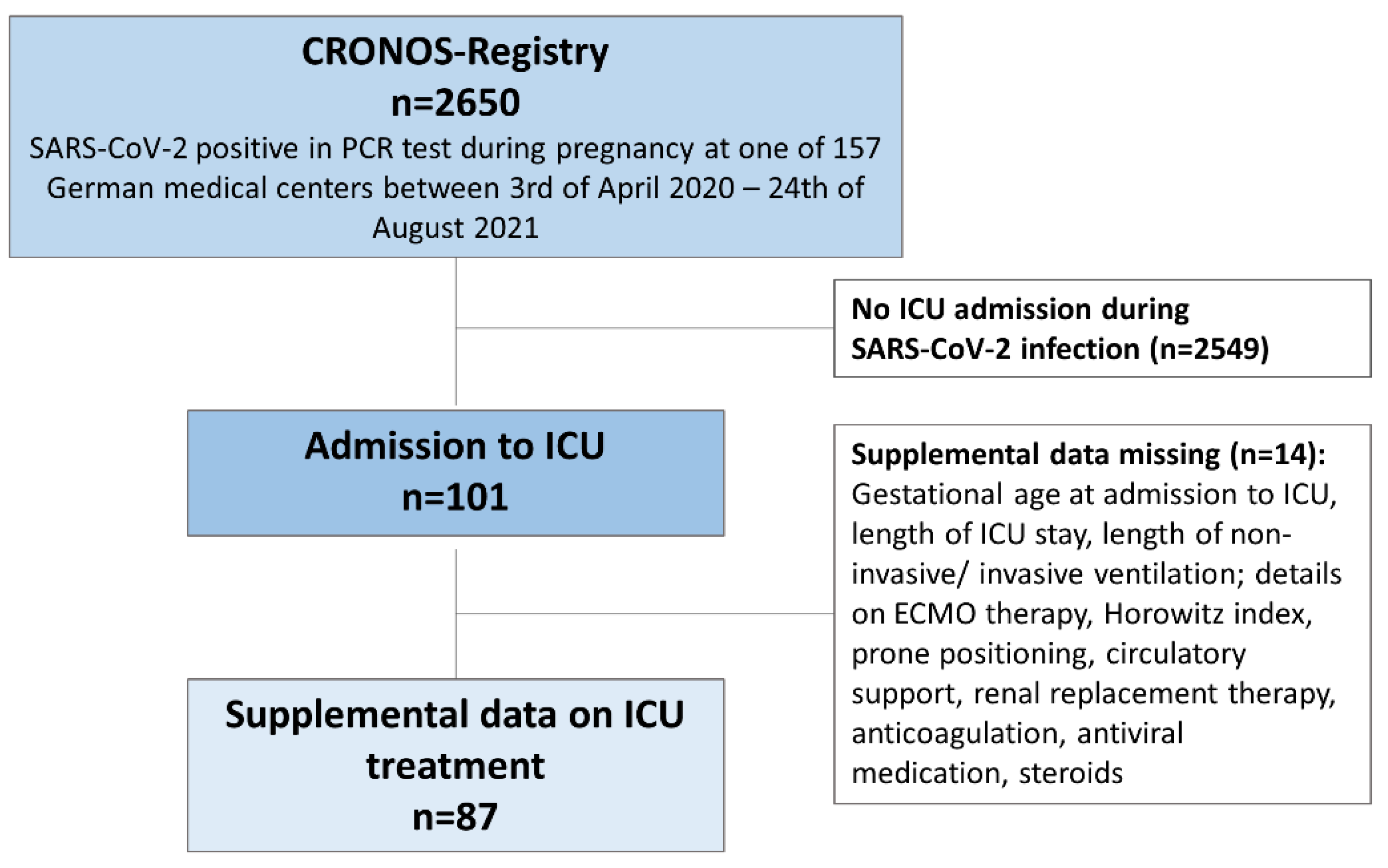

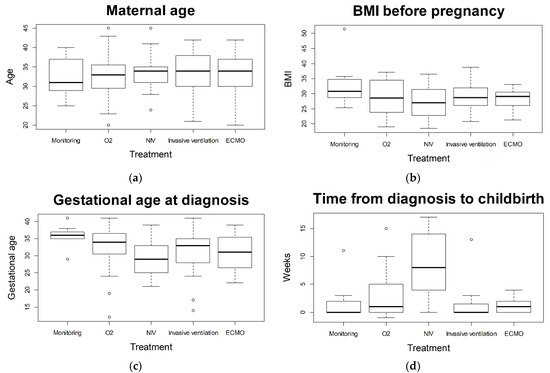

Data of pregnant women suffering from severe COVID-19 are sparse and knowledge is limited. Due to differences in health care systems, a regional analysis may be helpful. 101 women were analyzed that required ICU treatment subsequent to SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy based on the German CRONOS registry. The number of pregnant and postpartum women requiring intensive care treatment for COVID-19 is relatively low (here 101 out of 2650; 4%). However, in cases of severe disease progression, intensive care and escalation up to ECMO therapy may be required in spite of the low prevalence of pre-existing comorbidities. Maternal characteristics (such as maternal age, BMI, or pre-existing conditions) did not vary significantly following treatment stratification as a measure of disease severity. There were statistically significant differences with regard to gestational age at childbirth and rate of preterm delivery between treatment escalations. Although logistic regression could not identify a statistically significant difference between treatment requirements, grouping for non-invasive and invasive treatments revealed a significantly higher risk for premature birth. Admission to the ICU was associated with an elevated risk for a poor maternal and fetal outcome. Maternal mortality rate is higher for those requiring ICU treatment (5% in the ouresearch's cohort) than for pregnant women with COVID-19 (0.7%) or the comparison groups (0.2%), described by Allotey et al. [11]. Rate of stillbirth (6%) is also higher in ICU admitted patients compared to all pregnant women with COVID-19 (0.9%) and comparison groups (0.5%) [11]. Nevertheless, patients with severe COVID-19 not requiring invasive ventilation (non-invasive therapy as highest level of therapy) seem to benefit from treatment and show a high rate of recovery before childbirth without preterm labor. Previous studies and reviews have shown that most affected women with COVID-19 during pregnancy show no or mild symptoms [12]. Clinical presentation and symptoms seem to be similar as for non-pregnant adults [11][13][14]. The aOuthors'r analysis yields similar conclusions, with cough, dyspnea, and malaise being the most frequently reported symptoms [11][15]. Comparing symptomatic women to non-pregnant women with similar risk profiles (age, pre-existing conditions, ethnicity, etc.), the course of COVID-19 has been shown to be significantly more severe in pregnant women. Corresponding analyses of 409,462 symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infected women of reproductive age (15–44 years) showed a significantly increased risk in pregnant women for the need for intensive care (aRR 3.0; 95% CI 2.6–3.4) or death (aRR 1.7; 95% CI 1.2–2.4) as compared to non-pregnant women [16]. In comparison to pregnant women negative for SARS-CoV-2, an increased risk for maternal mortality has been described [17][18]. Furthermore, higher rates of in-hospital maternal death, preeclampsia, and thrombotic events have been reported [15][17]. In the abovementioned analyses, neither ICU treatment nor ICU treated patients were analyzed in detail. Easter et al. compared critically ill pregnant women with COVID-19 to non-pregnant patients, but a detailed analysis of differences in treatment modalities or severity of disease amongst ICU patients was not reported [19]. Describing the subgroup of SARS-CoV-2 positive pregnant women requiring ICU treatment according to severity status, as applied in this analysis, allows a more differentiated look at the different course of disease for SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy leading to ICU admission. With 101 of 2650 registered pregnant patients, the observed 4% ICU admission rate is similar to previously reported rates (3–10%) [14][15][16]. Although pregnant patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 had high rates of preterm delivery, caesarean section, and perinatal death [14][18][19], Easter et al. raised the question of whether or not delivery is required for non-obstetric indications among critically ill pregnant women [19]. TheIn authorsour cohort we observed a high number of iatrogenic deliveries with a subsequent high rate of preterm birth, particularly among invasively treated patients. A noteworthy number of patients required NIV therapy (15 out of 101) and invasive ventilation (2 out of 101) and recovered prior to childbirth without the need for premature delivery due to COVID-19. The authors thWe therefore suggest that a delivery is not necessarily required among ICU admitted pregnant women for non-obstetric reasons in otherwise stable patients. If the mother’s general condition deteriorates, the indication of delivery should be balanced between benefits for the mother (prone position, ECMO) and risks of prematurity for the infant. Some authors postulated an increase of maternal morbidity with progression of pregnancy [20]. Of thoseur ICU admitted patients, 71% tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the third trimester. Soheili et al. reported a higher risk of COVID-19 in the third trimester compared to the first and second trimester [21]. Th We authors found a statistically significant correlation between gestational age at diagnosis and severity of disease when comparing the group receiving insufflation of oxygen as highest form of treatment (later in gestational age) and the non-invasive ventilated patients (earlier in gestational age). The trend the authors owe observed showed a correlation between earlier week of gestational age at diagnosis and more severe course of disease (see Figure 1c).

3. Conclusions

References

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- RKI-Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2-COVID-19: Fallzahlen in Deutschland und Weltweit. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Fallzahlen.html (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Intensivbetten: Die Kapazitäten Schwinden. Available online: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/216577/Intensivbetten-Die-Kapazitaeten-schwinden (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Liu, H.; Wang, L.-L.; Zhao, S.-J.; Kwak-Kim, J.; Mor, G.; Liao, A.-H. Why are pregnant women susceptible to COVID-19? An immunological viewpoint. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020, 139, 103122.

- Lu, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Niu, P.; Yang, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Huang, B.; Zhu, N.; et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020, 395, 565–574.

- Behzad, S.; Aghaghazvini, L.; Radmard, A.R.; Gholamrezanezhad, A. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19: Radiologic and clinical overview. Clin. Imaging 2020, 66, 35–41.

- Wastnedge, E.A.N.; Reynolds, R.M.; Van Boeckel, S.R.; Stock, S.J.; Denison, F.C.; Maybin, J.A.; Critchley, H.O.D. Pregnancy and COVID-19. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 303–318.

- LoMauro, A.; Aliverti, A. Respiratory physiology of pregnancy. Breathe 2015, 11, 297–301.

- Di Mascio, D.; Khalil, A.; Saccone, G.; Rizzo, G.; Buca, D.; Liberati, M.; Vecchiet, J.; Nappi, L.; Scambia, G.; Berghella, V.; et al. Outcome of coronavirus spectrum infections (SARS, MERS, COVID-19) during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2020, 2, 100107.

- Pecks, U.; Kuschel, B.; Mense, L.; Oppelt, P.; Rüdiger, M. Pregnancy and SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Germany—The CRONOS Registry. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Online 2020, 117, 841–842.

- Allotey, J.; Stallings, E.; Bonet, M.; Yap, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Kew, T.; Debenham, L.; Llavall, A.C.; Dixit, A.; Zhou, D.; et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: Living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 370, 3320.

- Makvandi, S.; Mahdavian, M.; Kazemi-Nia, G.; Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Guest, P.C.; Karimi, L.; Sahebkar, A. The 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1321, 299–307.

- Matar, R.; Alrahmani, L.; Monzer, N.; Debiane, L.G.; Berbari, E.; Fares, J.; Fitzpatrick, F.; Murad, M.H. Clinical Presentation and Outcomes of Pregnant Women With Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, 521–533.

- Elshafeey, F.; Magdi, R.; Hindi, N.; Elshebiny, M.; Farrag, N.; Mahdy, S.; Sabbour, M.; Gebril, S.; Nasser, M.; Kamel, M.; et al. A systematic scoping review of COVID-19 during pregnancy and childbirth. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 47–52.

- Zaigham, M.; Andersson, O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: A systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 823–829.

- Zambrano, L.D.; Ellington, S.; Strid, P.; Galang, R.R.; Oduyebo, T.; Tong, V.T.; Woodworth, K.R.; Nahabedian, J.F.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Gilboa, S.M.; et al. Update: Characteristics of Symptomatic Women of Reproductive Age with Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status—United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1641–1647.

- Jering, K.S.; Claggett, B.L.; Cunningham, J.W.; Rosenthal, N.; Vardeny, O.; Greene, M.F.; Solomon, S.D. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Hospitalized Women Giving Birth with and without COVID-19. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 181, 714–717.

- Mullins, E.; Hudak, M.L.; Banerjee, J.; Getzlaff, T.; Townson, J.; Barnette, K.; Playle, R.; Perry, A.; Bourne, T.; Lees, C.C.; et al. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of COVID-19: Coreporting of common outcomes from PAN-COVID and AAP SONPM registries. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 57, 572–581.

- Easter, S.R.; Gupta, S.; Brenner, S.K.; Leaf, D.E. Outcomes of Critically Ill Pregnant Women with COVID-19 in the United States. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 122–125.

- Tug, N.; Yassa, M.; Köle, E.; Sakin, Ö.; Köle, M.Ç.; Karateke, A.; Yiyit, N.; Yavuz, E.; Birol, P.; Budak, D.; et al. Pregnancy worsens the morbidity of COVID-19 and this effect becomes more prominent as pregnancy advances. Turk. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 17, 149–154.

- Soheili, M.; Moradi, G.; Baradaran, H.R.; Soheili, M.; Mokhtari, M.M.; Moradi, Y. Clinical manifestation and maternal complications and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19: A comprehensive evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021, 1–14.