Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 5 by Vicky Zhou and Version 6 by Vicky Zhou.

An epidemiological relationship between urolithiasis and cardiovascular diseases has extensively been reported. Endothelial dysfunction is an early pathogenic event in cardiovascular diseases and has been associated with oxidative stress and low chronic inflammation in hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke or the vascular complications of diabetes and obesity.

- endothelial dysfunction

- oxidative stress

- urolithiasis

- kidney stones

1. Introduction

Nephrolithiasis is a worldwide public health problem affecting nowadays 5% to 9% of the European population and almost 12% of the North American people. It has high recurrence rates reaching 60% of the cases in 10 years. Consequences of nephrolithiasis range from the appearance of obstructive uropathy, frequently resulting in loss of work, need of hospitalization, or surgery, to kidney disease in the most severe cases. Budget-impact analyses based on 65 million population (France) have established the annual cost of urolithiasis in €590 million [1].

It has recently been suggested a significantly increased risk of kidney stone development secondary to diet factors and has been associated with pathologies such as obesity, metabolic syndrome or diabetes [2]. These alterations are also associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and epidemiological data indicate that obesity is an independent risk factor for the development of chronic kidney injury [3].

Endothelial dysfunction (ED) is an early pathogenic feature of cardiovascular morbidities, consisting of impaired vasodilation, angiogenesis and barrier function [4]. It has been related to metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, obesity or metabolic syndrome; all of them also associated with cardiovascular diseases [5]. The key role of oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of ED is well established [4].

Recently, ED has been linked to urolithiasis through clinical and experimental studies [6][7][8][9].

2. Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction

The vascular endothelium acts as an interphase that regulates the passage of nutrients, hormones and macromolecules from the blood to the surrounding tissue, but also ensures the fluidity of blood and contributes to homeostasis. Thus, the endothelium is now considered as the largest endocrine, autocrine and paracrine organ of the body, that secrets vasoactive and trophic mediators which regulate vascular tone, endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, coagulation, inflammation and permeability [10][11]. In response to flow-induced shear stress or to chemical signals, endothelial cells release vasodilator, antiaggregant and anti-inflammatory factors such as nitric oxide (NO), cyclooxygenase (COX)-derived prostacyclin (PgI2) or endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors (EDHFs), and on the other hand, vasoconstrictor, proaggregant and proliferative mediators such as thromboxane A2 (TXA2), ROS and endothelin 1 (ET-1) [12]. Endothelial cells also modulate the immune reaction by the recruitment of inflammatory cells through the induction of leucocyte adhesion molecules, cytokines or ROS [4][13].

Endothelial dysfunction (ED) consists of an impaired vasodilator response and altered angiogenesis and barrier function, along with an elevated expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic factors, because of an endothelial maladaptation to mechanical, metabolic or oxidative stresses. ED is considered to be the first stage of vascular disorders and atherogenesis and it is considered to occur in the preclinical phase of vascular disease, predisposing it to complications [10][14].

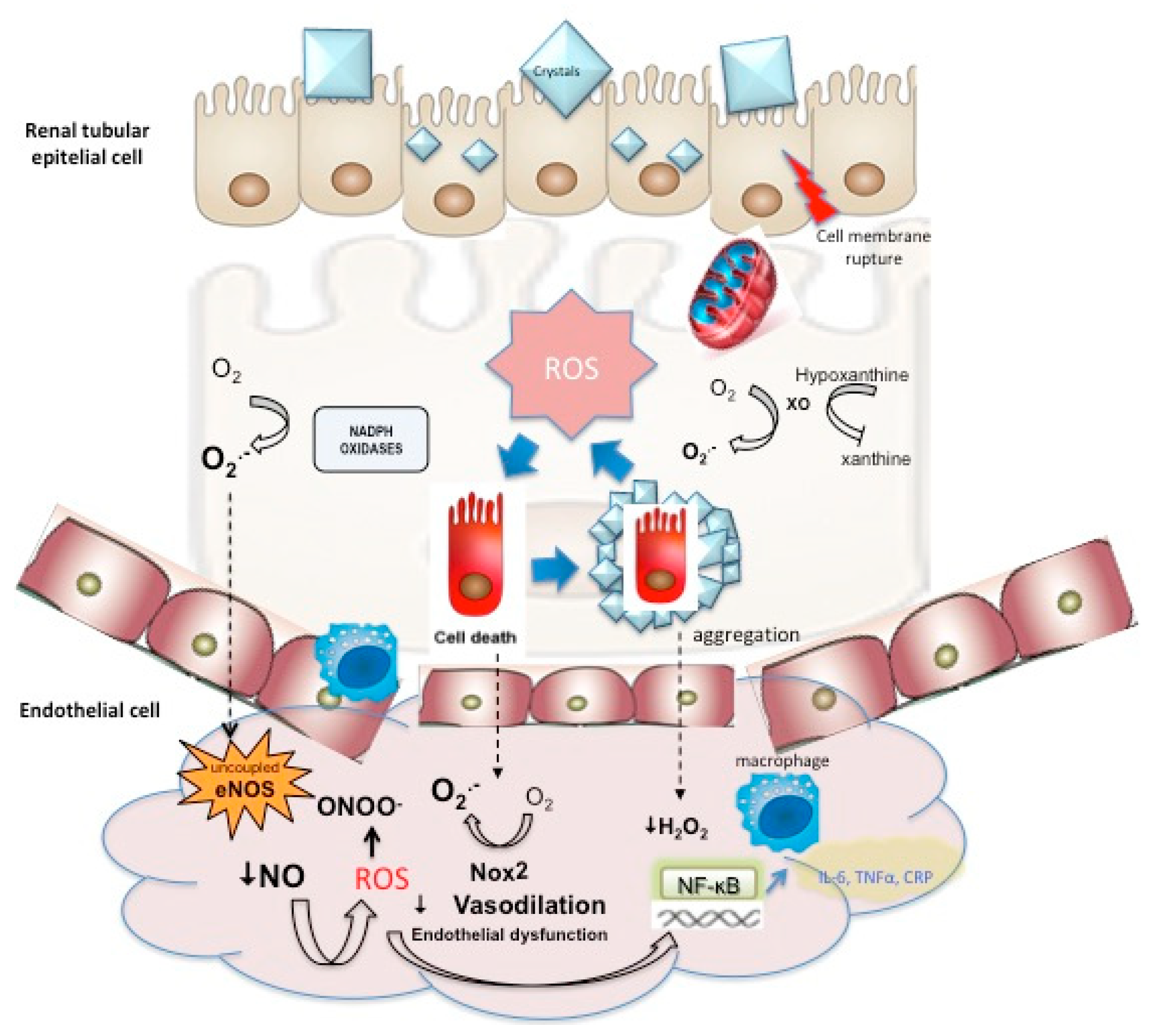

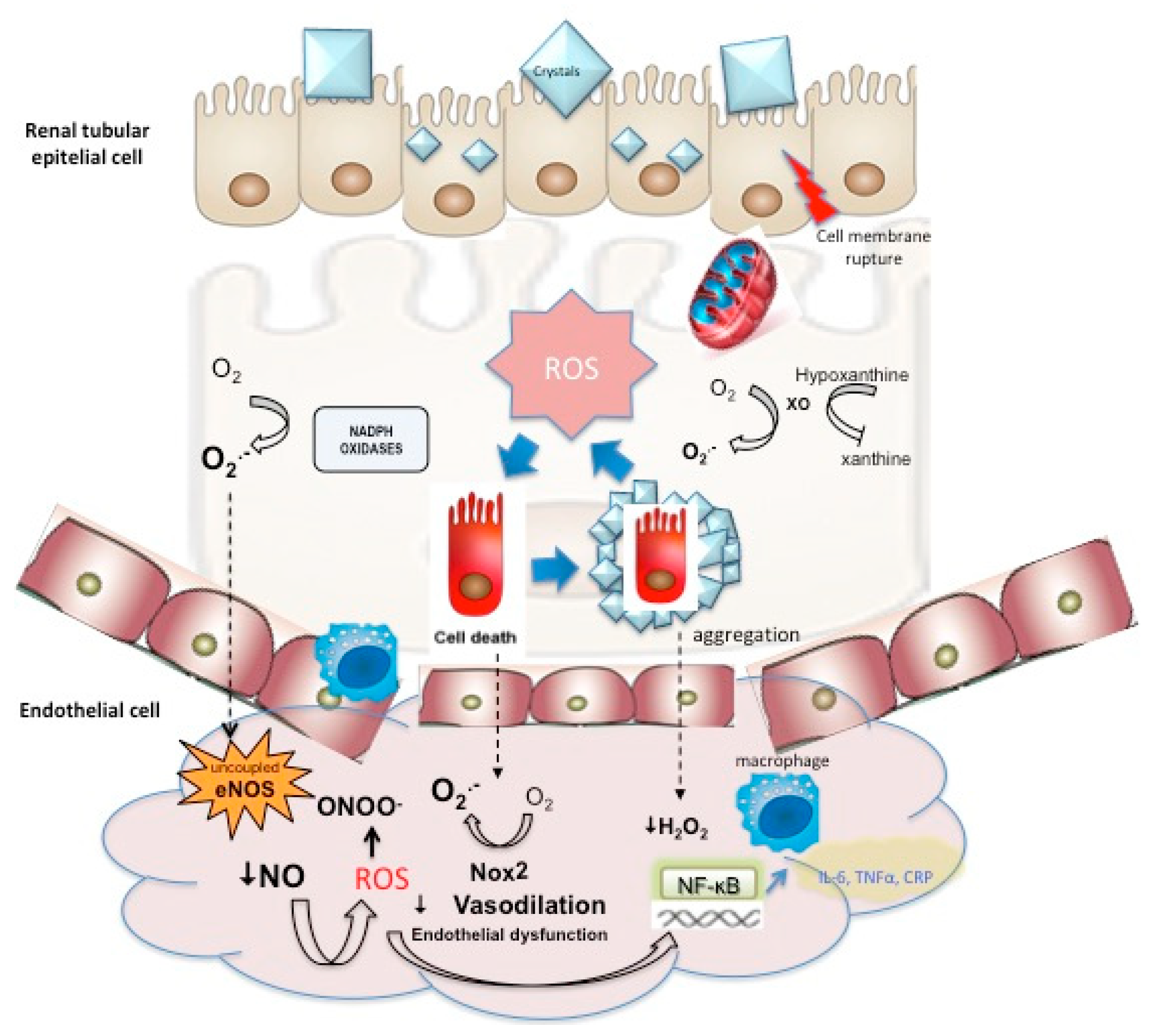

The key role of oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of ED is well established. Despite several factors that can compromise the availability of NO, which protects the vascular wall from the events leading to atherosclerosis, one of the primary causes of ED is oxidative stress in many metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. NO produced by eNOS interacts and is rapidly inactivated, by O2−-producing peroxynitrite, a highly potent oxidant and toxic radical that injures DNA, proteins and lipids, and also inactivates PgI2, thus contributing to impaired PgI2-mediated vasodilation and antiaggregation. Nicotinamida adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase is considered to be a major source of vascular ROS generation under some pathological conditions. Augmented ROS production activates the oxidative stress-sensitive nuclear transcription factor (NF-κB) that directly up-regulates NADPH oxidase and regulates the expression of genes encoding adhesion molecules, COX-2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP), which in turn may activate NADPH oxidase and ROS-generation, impairing endothelial function [4][10].

Oxidative stress is considered to be the main trigger factor for the vascular complications in diabetes Mellitus, including diabetic nephropathy which leads to CKD. Increased ROS production is mainly derived from mitochondria and NADPH oxidase, and also from the polyol pathway, uncoupling NOS, xanthine oxidase or advanced glycation, which in turn results in a thickening of the glomeruli basement membrane, mesangial expansion, hypertrophy and podocyte loss [15][16]. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and ED is also well established. Microangiopathy is one of the main complications of diabetes and is a key factor for the development of retinopathy, nephropathy and diabetic foot. In type 1 diabetes, ED is a consequence of hyperglycemia-associated oxidative stress, while in type 2 diabetes, other factors, such as dyslipidemia, hyperinsulinemia and an abnormal release of adipose tissue-derived adipokines, are also associated [15][17][11].

Overweight and obesity-associated ED was first reported in clinical studies demonstrating blunted increases in leg blood flow in response to the administration of endothelium-dependent agonists in obese patients with an augmented body mass index (BMI) [18]. The vasculature and endothelial cells are affected by nutrient overload, suggesting that the susceptibility to oxidative stress, inflammation and insulin resistance is greater than in other tissue types [5]. Altered production of adipokines and the elevated levels of free fatty acids (FFA) induce OS, leading to a reduced NO availability, an imbalance between vasodilator and vasoconstrictor prostanoids, impairment of EDHF–mediated responses, and elevation of vasoconstrictor and proatherogenic factors such as ET-1. Oxidative stress and inflammation play an essential role in the development of ED. Hypertrophy of adipose tissue leads to a proinflammatory phenotype marked by an increased ROS production and an elevation of circulating of proinflammatory cytokines as IL-6, TNFα, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) [4]. Vascular oxidative stress derived from COX-2, Nox1 and Nox2 underlies kidney ED and inflammation in obesity [19][20][21].

Other traditional cardiovascular disease-associated factors, such as hyperlipidemia, smoking or hypertension, have also been associated with ED and oxidative stress. Furthermore, new clinical and environmental features have been also pointed out. Mental stress has been shown to activate the immune system and lead to adverse cardiovascular effects [22]. Chronic autoimmune diseases such as lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis or severe psoriasis also increase cardiovascular risk through ED [23][24][25][26]. Aging is also associated with arterial stiffness and ED, as a result, the incidence and frequency of cardiovascular complications is higher among the elderly [27]. COVID 2019 has also been pointed out as an endothelial disease, and the consequent endotheliopathy is responsible for inflammation, cytokine storm, coagulopathy and oxidative stress [28].

3. Endothelial Dysfunction: A Clinical Feature Highly Associated to Nephrolithiasis

Urolithiasis and cardiovascular disorders have extensively been related through epidemiological studies (Table 1). Three metanalysis have been reported at the time [29][30][31]. All of them have observed a significant association between CAD and urolithiasis with RR between 1.20 and 1.24. Two of them (Peng and Liu) have also reported a significant association of lithiasis with stroke, and more specifically with MI and with coronary revascularization. Analysis of subgroups observed inconclusive results at this point; Peng et al. observed a higher risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) in men (RR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.02–1.49) than in women (RR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.92–1.11), although women showed higher risk for stroke (RR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.03–1.21) than men (RR: 1.03 95%; CI: 0.98–1.09), and for MI (RR: 1.37 95% CI: 1.13–1.67 vs. 1.01 95% CI: 0.92–1.11–1.49). Likewise, a significantly higher risk of CHD has been reported in females (RR: 1.43; 95% CI: 1.12–1.82) compared with men, 95% (RR: 1.14; CI: 0.98–1.38) [31], and in the same way, Liu [30] observed an increased risk for MI in women (HR: 1.49; CI: 1.21–1.82) compared with men, in which no association was observed (HR: 1.15; CI: 0.89–1.50). In addition to these studies, subpopulations of American and Asian lithiasic patients were more susceptible to CHD and stroke [29]. Kim et al. have reported the most recent study, not included in any of three metanalysis, for the evaluation of the association between nephrolithiasis and stroke. Results have shown a higher risk of ischemic stroke in nephrolithiasis patients (RR: 1.13; 95% CI 1.06–1.21). The subgroup analysis resulted significant for young women and middle aged men [32]. Chung’s study, neither included in the metanalysis, also assessed the relationship between urolithiasis and stroke. The design of the study was very similar to that of Kim´s study, but was a cohorts study with a follow up of five years. After adjusting for hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, gout cardiovascular diseases and urbanization level, urolithiasis remained as a significant risk factor for the development of stroke (HR: 1.43; 95% CI 1.35–1.50, p < 0.0001) [33]. Aydin et al. performed a single center, cross sectional, case control study conducted on 200 consecutive patients with CaOx stone disease, age and sex matched with 200 controls without any acute or chronic disease. Results showed that patients with CaOx stones had a higher Framingam Risk score (OR: 8.36; 95% CI 3.81–18.65, p < 0.0001) and SCORE risk score (OR: 3.02; 95% CI 1.30–7.02) compared with controls. The results also indicated that patients with urolithiasis had higher levels of total cholesterol (p < 0.0001), lower levels of HDL-cholesterol (p < 0.0001), and higher systolic blood pressure (p < 0.0001) [34]. In another case control study that examined the impact of CHD risk factors on CaOx stone formation, it was concluded that CaOx formers are significantly associated with several CHD risk factors, including smoking habit, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and obesity [35]. Arterial structure has also been evaluated in nephrolithiasic patients. Kim et al. demonstrated the association of coronary artery calcification with urolithiasis, assessed by cardiac computed tomography [36], while Fabris et al. confirmed an increased arterial stiffness in a study conducted on 42 idiopathic calcium stone formers [37]. Furthermore, the calcium sensing receptor, a G protein-coupled receptor, that is expressed in calcitropic tissues as the parathyroid gland and the kidney has been postulated to be the connection between nephrolithiasis and vascular calcification [38]. On the other hand, three studies have assessed endothelial function in kidney stone formers by using the Celermajer method, by measuring the flow-mediated dilation (%FMD), as an endothelium dependent response to shear stress [39]. All of them showed a significant lower %FMD in lithiasic patients [7][8][40]. No longitudinal cohort studies have been conducted on lithiasic patients with normal endothelial function in order to establish whether nephrolithiasis can be considered as a prior risk factor for ED. A significant relationship between urolithiasic risk factors such as urine calcium/creatinine index and %FMD has also been reported [8]. On the other side, Saenz et al. studied the behavior of inflammation, OS and ED serum markers (CRP, IL6, MDA, VCAM-1 and asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA)) in relation to %FMD in lithiasic patients, but no relationship could be demonstrated [7]. Evaluation of stone and urine composition has been another approach used for the study of the relationship between cardiovascular disorders and kidney stone formation. Barbagli et al. have recently examined the composition of the stones and the urine metabolic profile of lithiasic patients with and without cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) (MI, angina, coronary revascularization or surgery of calcified heart valves). Patients with CVD had significantly lower 24 h urinary excretions for citrate and magnesium (both of them kidney stone risk factors). No differences in stone composition were found between groups [41]. Proteomic analysis of urine in pediatric stone formers and in relation to patients’ kidney stone risk factors, including hypercalciuria and hypocitraturia, has also been performed. Most of the proteins upregulated in both groups were involved in coagulation, fibrinolysis, metabolism and OS, all of them CVD risk factors. These results also suggest shared risk factors between urolithiasis and CVD through the proteomic urine analysis [42]. Hyperoxaluria has also been reported also to cause systemic ED in animal models and cell culture studies. Induction of hyperoxaluria in a rat model has been related to an increased systemic and renal tissue ADMA. ADMA is an endogenous competitive inhibitor of NOS, linked to ED and atherosclerosis. These results again suggest the interaction between the renal epithelial injury triggered by the hyperoxaluria, mediated by OS, and ED. The close contact between proximal tubular cells and endothelial cells makes hyperoxaluria affect the capacity of synthetizing vasoactive substances, growth modulators and inflammatory factors by endothelial cells [6] (Figure 1). Another cell culture study with co-incubation of endothelial and epithelial cells has suggested the protective role of endothelial cells against the epithelial tubular cell injury, induced by hyperoxaluria, by decreasing OS in renal tissue with potent antioxidants, which antagonize ADMA, and restores endothelial function [43].Table 1. Characteristics of metanalysis and clinical studies in which association between urolithiasis and cardiovascular morbidity has been studied. CHD: Coronary heart disease. CAD: Coronary artery disease. MI: Myocardial infarction.

| Type of Study | Number of Patients | Pathological Condition | Association | Reference | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metanalysis | 3,658,360 participants 157,037 urolithiasis |

CHD and stroke | CHD: RR = 1.24 (95% CI 1.14–1.36) MI: RR = 1.24 (95% CI 1.10–1.40) Stroke: RR = 1.21 (95% CI 1.06–1.38) |

Peng and Zheng, 2017 | [29] | ||||||||

| Metanalysis | 34,244,855 controls 52,791 urolithiasis |

CAD | RR = 1.24 (95% CI 1.10–1.40) Women: RR = 1.43 (95% CI 1.12–1.82) Men: RR = 1.14 (95% CI 0.94–1.38) |

Cheungpasitporn et al., 2014 | [31] | ||||||||

| Metanalysis | 3,558,053 controls 49,597 urolithiasis |

CAD Stroke MI Coronary revascularization |

CAD: RR = 1.19 (95% CI 1.05–1.35) Stroke: RR = 1.40 (95% CI 1.20–1.64) MI: RR = 1.29 (95% CI 1.10–1.52) CR: RR = 1.31 (95% CI 1.05–1.65) Male cohorts no association |

Liu et al., 2014 | [30] | ||||||||

| Cohorts Longitudinal |

90,544 controls 22,636 urolithiasis |

Ischemic Stroke | HR = 1.13 (95% CI 1.06–1.21) | Kim et al., 2019 | [32] | ||||||||

| Cohorts Longitudinal |

5571 urolithiasis | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease | OR: 1.03 (95% CI 1.06–1.21) No association |

Glover et al., 2016 | [44] | ||||||||

| Cohorts Longitudinal |

40,773 controls 40,773 urolithiasis |

MI Stroke Cardiovascular events |

M.I: HR: 1.31 (95% CI 1.09–1.56) Stroke: HR: 1.39 (95% CI 1.24–1.55) CE: HR: 1.38 (95% CI 1.25–1.51) |

Hsu et al., 2016 | [45] | ||||||||

| Cohorts Longitudinal |

3,195,452 controls 25,532 urolithiasis |

MI Revascularization |

MI: HR = 1.40 (95% CI 1.30–1.51) Revasc.: HR = 1.63 (95% CI 1.51–1.76) Stroke: HR = 1.26 (95% CI 1.12–1.42) |

Alexander et al., 2014 | [46] | ||||||||

| Self-reported history of urolithiasis Longitudinal |

196,357 women 45,748 men 19,678 urolithiasis |

MI Revascularization |

HR = 1.30 (95% CI 1.04–1.62) (women) HR = 1.26 (95% CI 1.07–1.55) (women) |

Ferraro et al., 2013 | [47] | ||||||||

| Cohorts Longitudinal |

125,905 matched controls 25,181 urolithiasis |

Stroke | HR = 1.43 (95% CI 1.35–1.50) | Chung et al., 2012 | [33] | ||||||||

| Cross sectional case-control study | 200 CaOx stone formers | Cardiovascular disease Mortality |

OR = 8.36 (95% CI 3.81–16.85) OR = 3.02 (95% CI 1.30–7.02) |

Aydin et al., 2011 | [34] | ||||||||

| Self-reported history of urolithiasis Cross sectional |

23,346 | MI Stroke |

OR = 1.34 (95% CI 1–1.79) OR = 1.33 (95% CI 1.02–1.74) |

Domingos and Serra, 2011 | [48] | ||||||||

| Cross sectional study Retrospective cohort |

10,860 control 4564 cases |

MI | HR = 1.31 (95% CI 1.02–1.69) | Rule et al., 2010 | [49] | ||||||||

| Cross sectional study Retrospective cohort |

Females cohort of 9704 426 nephrolithiasis |

MI | RR = 1.78 (95% CI 1.22–2.62) | Eisner et al., 2009 | [50] | ||||||||

| Cohorts Longitudinal |

10,938 normal blood pressure individuals 56 strokes |

Stroke | 3.6% urolithiasisin stroke patients 0.5% urolithiasis in no stroke individuals |

Li et al., 2009 | [51] | ||||||||

| Retrospective cohort | 1316 cases | MI | Westlund et al., 1973 | [52] | |||||||||

| Cross sectional study | 2000 men | CHD | No association | Ljunghall et al., 1976 | [53] | ||||||||

| Cross sectional study | 13,418 control men 404 current kidney stone formers 1231 past kidney stone formers |

Risk factors for coronary disease: BMI, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia and chronic kidney disease | Multivariate adjusted OR significant: Overweight/obesity ( | p | < 0.001), hypertension ( | p | < 0.001), gout/hyperuricemia ( | p | < 0.001), chronic kidney disease ( | p | < 0.001) in past and current kidney stone formers | Ando et al., 2013 | [54] |

| Cross sectional case-control study | 187 Controls 181 CaOx stone formers |

Risk factors for coronary disease: BMI, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperuricemia, hypercholesterolemia, smoking habit and current alcohol use | Multivariate adjusted OR significant: smoking habit (OR: 4.41, | p | < 0.0001), hypertension (OR: 3.57, | p | < 0.0001), hypercholesterolemia (OR: 2.74, | p | < 0.001), chronic kidney disease ( | p | < 0.001) | Hamano et al., 2005 | [35] |

| Cross sectional study | 27 control 27 lithiasic patients |

Endothelial dysfunction (Celermajer method) | %FMD 11.85% (SE: 2.78 lower in lithiasic patients. | p | < 0.001 | Sáenz-Medina et al., 2021 | [7] | ||||||

| Cross sectional study | 1.-MetS- SD−: 93 2.-MetS- SD+: 93 3.-MetS+ SD−: 93 4.-MetS+ SD+: 93 |

Endothelial dysfunction (Celermajer method) | 1 vs. 2: | p | < 0.001 1 vs. 3: | p | < 0.001 1 vs. 4: | p | < 0.001 | Yazici et al., 2020 | [40] | ||

| Cross sectional study | 60 control 60 lithiasic patients |

Endothelial dysfunction (Celermajer method) | FMD% Lithiasis: 6.49 ± 3.52 Control: 10.50 ± 5.10 | p | < 0.0001 | Yencilek et al., 2017 | [8] |

Figure 1. Interaction between oxidative stress-mediated epithelial cell injury, cell death, and stone formation with endothelial dysfunction triggered by impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation augmented ROS and inflammatory response.

4. Concluding Remarks

Nephrolithiasis is a worldwide public health disorder of increasing incidence, especially in industrialized countries in which diet factors have been pointed out as responsible of the higher urolithiasis prevalence. Cardiovascular disorders have been independently associated to urolithiasis disorders and lithiasic patients present a higher incidence of cardiovascular diseases, myocardial infarction and stroke with relative risks between 1.20 and 1.24.

Oxidative stress has been pointed out as an important factor in lithogenesis and a trigger factor for the vascular complications of low-chronic inflammation diseases such as obesity, diabetes or hypertension. Endothelial dysfunction is the preclinical stage of atherosclerosis and is also highly associated with cardiovascular morbidities. Oxidative stress and inflammation play an important role in the pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction. In addition, endothelial dysfunction has been related to urolithiasis, so it may be considered as an intermediate and changeable feature between urolithiasis and cardiovascular disorders.

Special attention must be paid for some concomitant comorbidities associated with urolithiasis. Active treatment of hypertension or hyperlipidemia with angiotensin receptor blockers or statins allows to take advantage to prevent endothelial dysfunction through their pleiotropic effects and prevent the cardiovascular morbidity. On the other side, further studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms linking urolithiasis and endothelial dysfunction evidenced by epidemiological studies.

Abbreviations

| ADMA | asymmetric dimethylarginine | ||

| BMI | body max index | ||

| CAD | coronary artery disease | ||

| CaOx | calcium oxalate | ||

| CHD | CaP | coronary heart disease | calcium phosphate |

| CKD | CHD | Chronic kidney disease | coronary heart disease |

| COX | CKD | cyclooxygenase | Chronic kidney disease |

| CRP | COX | C-reactive protein | cyclooxygenase |

| ED | CRP | Endothelial dysfunction | C-reactive protein |

| EDHFs | ED | endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors | Endothelial dysfunction |

| eNOS | EDHFs | endothelial nitric oxide synthase | endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors |

| ET-1 | eNOS | endothelin-1 | endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| FFA | ET-1 | free fatty acids | endothelin-1 |

| MCP-1 | FFA | monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 | free fatty acids |

| NADPH | Gpx | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate | glutathione peroxidase |

| NF-κB | ICAM-1 | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells | intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| Nox | MCP-1 | NADPH oxidase | monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| PAI-1 | MnSOD | plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 | manganese superoxide dismutase |

| ROS | NADPH | Reactive oxygen species | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| TNFα | NF-κB | tumour necrosis factor α | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| TXA2 | Nos | thromboxane A2 | nitric oxide synthase |

| VCAM-1 | Nox | vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 | NADPH oxidase |

| ONOO | |

| − | |

| Peroxynitrite | |

| OPN | |

| osteopontin | |

| PAI-1 | |

| plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 | |

| Prx | |

| Peroxiredoxins | |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SDMA | symmetric dimethylarginine |

| TNFα | tumour necrosis factor α |

| Trx | thioredoxin |

| TXA2 | thromboxane A2 |

| VCAM-1 | vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| XO | xanthine oxidase |

References

- Lotan, Y.; Jiménez, I.B.; Lenoir-Wijnkoop, I.; Daudon, M.; Molinier, L.; Tack, I.; Nuijten, M.J. Primary Prevention of Nephrolithiasis Is Cost-Effective for a National Healthcare System. BJU Int. 2012, 110, E1060–E1067.

- Jeong, I.G.; Kang, T.; Bang, J.K.; Park, J.; Kim, W.; Hwang, S.S.; Kim, H.K.; Park, H.K. Association Between Metabolic Syndrome and the Presence of Kidney Stones in a Screened Population. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2011, 58, 383–388.

- De Vries, A.P.; Ruggenenti, P.; Ruan, X.Z.; Praga, M.; Cruzado, J.M.; Bajema, I.M.; D'Agati, V.D.; Lamb, H.J.; Barlovic, D.P.; Hojs, R.; et al. Fatty Kidney: Emerging Role of Ectopic Lipid in Obesity-Related Renal Disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 417–426.

- Contreras, C.; Sanchez, A.; Prieto, D. Endothelial Dysfunction, Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 12, 412–426.

- Kim, F.; Pham, M.; Maloney, E.; Rizzo, N.O.; Morton, G.J.; Wisse, B.E.; Kirk, E.A.; Chait, A.; Schwartz, M.W. Vascular Inflammation, Insulin Resistance, and Reduced Nitric Oxide Production Precede the Onset of Peripheral Insulin Resistance. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 1982–1988.

- Aydın, H.; Yencilek, F.; Mutlu, N.; Çomunoğlu, N.; Koyuncu, H.H.; Sarıca, K. Ethylene Glycol Induced Hyperoxaluria Increases Plasma and Renal Tissue Asymmetrical Dimethylarginine in Rats: A New Pathogenetic Link in Hyperoxaluria Induced Disorders. J. Urol. 2010, 183, 759–764.

- Sáenz-Medina, J.; Martinez, M.; Rosado, S.; Durán, M.; Prieto, D.; Carballido, J. Urolithiasis Develops Endothelial Dysfunction as a Clinical Feature. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 722.

- Yencilek, E.; Sarı, H.; Yencilek, F.; Yeşil, E.; Aydın, H. Systemic Endothelial Function Measured by Flow-Mediated Dilation Is Impaired in Patients with Urolithiasis. Urolithiasis 2016, 45, 545–552.

- Yazici, O.; Narter, F.; Erbin, A.; Aydin, K.; Kafkasli, A.; Sarica, K. Effect of Endothelial Dysfunction on the Pathogenesis of Urolithiasis in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Aging Male 2020, 23, 1082–1087.

- Vanhoutte, P.M.; Shimokawa, H.; Feletou, M.; Tang, E.H.C. Endothelial Dysfunction and Vascular Disease—A 30th Anniversary Update. Acta Physiol. 2017, 219, 22–96.

- Bakker, W.; Eringa, E.C.; Sipkema, P.; van Hinsbergh, V.W.M. Endothelial Dysfunction and Diabetes: Roles of Hyperglycemia, Impaired Insulin Signaling and Obesity. Cell Tissue Res. 2009, 335, 165–189.

- Mangana, C.; Lorigo, M.; Cairrao, E. Implications of Endothelial Cell-Mediated Dysfunctions in Vasomotor Tone Regulation. Biology 2021, 1, 15.

- Vanhoutte, P.M.; Shimokawa, H.; Tang, E.H.C.; Feletou, M. Endothelial Dysfunction and Vascular Disease. Acta Physiol. 2009, 196, 193–222.

- Davignon, J.; Ganz, P. Role of Endothelial Dysfunction in Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2004, 109 (Suppl. S1), III-27.

- Ratliff, B.B.; Abdulmahdi, W.; Pawar, R.; Wolin, M.S. Oxidant Mechanisms in Renal Injury and Disease. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2016, 25, 119–146.

- Forbes, J.M.; Coughlan, M.T.; Cooper, M.E. Oxidative Stress as a Major Culprit in Kidney Disease in Diabetes. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1446–1454.

- Sedeek, M.; Nasrallah, R.; Touyz, R.M.; Hébert, R.L. NADPH Oxidases, Reactive Oxygen Species, and the Kidney: Friend and Foe. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 1512–1518.

- Steinberg, H.O.; Chaker, H.; Leaming, R.; Johnson, A.; Brechtel, G.; Baron, A.D. Obesity/Insulin Resistance Is Associated with Endothelial Dysfunction. Implications for the Syndrome of Insulin Resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 97, 2601–2610.

- Muñoz, M.; López-Oliva, M.E.; Rodríguez, C.; Martínez, M.P.; Sáenz-Medina, J.; Sánchez, A.; Climent, B.; Benedito, S.; García-Sacristán, A.; Rivera, L.; et al. Differential Contribution of Nox1, Nox2 and Nox4 to Kidney Vascular Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction in Obesity. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101330.

- Rodríguez, C.; Sánchez, A.; Sáenz-Medina, J.; Muñoz, M.; Hernández, M.; López, M.; Rivera, L.; Contreras, C.; Prieto, D. Activation of AMP Kinase Ameliorates Kidney Vascular Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Rodent Models of Obesity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 4085–4103.

- Muñoz, M.; Sánchez, A.; Martinez, P.; Benedito, S.; López-Oliva, M.-E.; García-Sacristán, A.; Hernández, M.; Prieto, D. COX-2 Is Involved in Vascular Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction of Renal Interlobar Arteries from Obese Zucker Rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 84, 77–90.

- Marvar, P.J.; Harrison, D.G. Stress-Dependent Hypertension and the Role of T Lymphocytes. Exp. Physiol. 2012, 97, 1161–1167.

- Hak, A.E.; Karlson, E.W.; Feskanich, D.; Stampfer, M.J.; Costenbader, K.H. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Results from the nurses’ Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61, 1396–1402.

- Vena, G.A.; Vestita, M.; Cassano, N. Psoriasis and Cardiovascular Disease. Dermatol. Ther. 2010, 23, 144–151.

- Soltesz, P.; Kerekes, G.; Dér, H.; Szucs, G.; Szanto, S.; Kiss, E.; Bodolay, E.; Zeher, M.; Timar, O.; Szodoray, P.; et al. Comparative Assessment of Vascular Function in Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases: Considerations of Prevention and Treatment. Autoimmun. Rev. 2011, 10, 416–425.

- Murdaca, G.; Colombo, B.M.; Cagnati, P.; Gulli, R.; Spanò, F.; Puppo, F. Endothelial Dysfunction in Rheumatic Autoimmune Diseases. Atherosclerosis 2012, 224, 309–317.

- Ras, R.T.; Streppel, M.T.; Draijer, R.; Zock, P. Flow-Mediated Dilation and Cardiovascular Risk Prediction: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 344–351.

- Fodor, A.; Tiperciuc, B.; Login, C.; Orasan, O.H.; Lazar, A.L.; Buchman, C.; Hanghicel, P.; Sitar-Taut, A.; Suharoschi, R.; Vulturar, R.; et al. Endothelial Dysfunction, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in COVID-19—Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 8671713.

- Peng, J.P.; Zheng, H. Kidney Stones May Increase the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke: A PRISMA-Compliant Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, E7898.

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, J.; Xie, L.; Li, T.; He, Y.; Qin, X.; Zhao, J. Kidney Stones and Cardiovascular Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2014, 64, 402–410.

- Cheungpasitporn, W.; Mao, M.A.; O’Corragain, O.A.; Edmonds, P.J.; Erickson, S.B.; Thongprayoon, C. The Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Patients with Kidney Stones: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 6, 580.

- Kim, S.Y.; Song, C.M.; Bang, W.; Lim, J.-S.; Park, B.; Choi, H.G. Nephrolithiasis Predicts Ischemic Stroke: A Longitudinal Follow-up Study Using a National Sample Cohort. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 16, 1050–1056.

- Chung, S.-D.; Liu, S.-P.; Keller, J.J.; Lin, H.-C. Urinary Calculi and an Increased Risk of Stroke: A Population-Based Follow-up Study. BJU Int. 2012, 110, E1053–E1059.

- Aydin, H.; Yencilek, F.; Erihan, I.B.; Okan, B.; Sarica, K. Increased 10-Year Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality Risk Scores in Asymptomatic Patients with Calcium Oxalate Urolithiasis. Urol. Res. 2011, 39, 451–458.

- Hamano, S.; Nakatsu, H.; Suzuki, N.; Tomioka, S.; Tanaka, M.; Murakami, S. Kidney Stone Disease and Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease. Int. J. Urol. 2005, 12, 859–863.

- Kim, S.; Chang, Y.; Sung, E.; Kang, J.G.; Yun, K.E.; Jung, H.-S.; Hyun, Y.Y.; Lee, K.-B.; Joo, K.J.; Shin, H.; et al. Association Between Sonographically Diagnosed Nephrolithiasis and Subclinical Coronary Artery Calcification in Adults. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 71, 35–41.

- Fabris, A.; Ferraro, P.M.; Comellato, G.; Caletti, C.; Fantin, F.; Zaza, G.; Zamboni, M.; Lupo, A.; Gambaro, G. The Relationship Between Calcium Kidney Stones, Arterial Stiffness and Bone Density: Unraveling the Stone-Bone-Vessel Liaison. J. Nephrol. 2014, 28, 549–555.

- Liu, C.-J.; Cheng, C.-W.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Huang, H.-S. Crosstalk Between Renal and Vascular Calcium Signaling: The Link Between Nephrolithiasis and Vascular Calcification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3590.

- Celermajer, D.S.; Sorensen, K.E.; Bull, C.; Robinson, J.; Deanfield, J. Endothelium-Dependent Dilation in the Systemic Arteries of Asymptomatic Subjects Relates to Coronary Risk Factors and Their Interaction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1994, 24, 1468–1474.

- Yazici, O.; Aydin, K.; Temizkan, S.; Narter, F.; Erbin, A.; Kafkasli, A.; Cubuk, A.; Aslan, R.; Sarıca, K. Relationship Between Serum Asymmetrical Dimethylarginine Level and Urolithiasis. East. J. Med. 2020, 25, 366–370.

- Bargagli, M.; Moochhala, S.; Robertson, W.G.; Gambaro, G.; Lombardi, G.; Unwin, R.J.; Ferraro, P.M. Urinary Metabolic Profile and Stone Composition in Kidney Stone Formers with and Without Heart Disease. J. Nephrol. 2021, in press.

- Kovacevic, L.; Lu, H.; Caruso, J.A.; Kovacevic, N.; Lakshmanan, Y. Urinary Proteomics Reveals Association Between Pediatric Nephrolithiasis and Cardiovascular Disease. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2018, 50, 1949–1954.

- Sarıca, K.; Aydin, H.; Yencilek, F.; Telci, D.; Yilmaz, B. Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells Accelerate Oxalate-Induced Apoptosis of Human Renal Proximal Tubule Epithelial Cells in Co-Culture System Which Is Prevented by Pyrrolidine Dithiocarbamate. Urol. Res. 2012, 40, 461–466.

- Glover, L.; Bass, M.A.; Carithers, T.; Loprinzi, P.D. Association of Kidney Stones with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Among Adults in the United States: Considerations by Race-Ethnicity. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 157, 63–66.

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Huang, P.-H.; Leu, H.-B.; Su, Y.-W.; Chiang, C.-H.; Chen, J.-W.; Chen, T.-J.; Lin, S.-J.; Chan, W.-L. The Association Between Urinary Calculi and Increased Risk of Future Cardiovascular Events: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. J. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 463–470.

- Alexander, R.T.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Wiebe, N.; Bello, A.; Samuel, S.; Klarenbach, S.W.; Curhan, G.C.; Tonelli, M. Kidney Stones and Cardiovascular Events: A Cohort Study. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 9, 506–512.

- Ferraro, P.M.; Taylor, E.N.; Eisner, B.H.; Gambaro, G.; Rimm, E.B.; Mukamal, K.J.; Curhan, G.C. History of Kidney Stones and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013, 310, 408–415.

- Domingos, F.; Serra, A. Nephrolithiasis Is Associated with an Increased Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 26, 864–868.

- Rule, A.D.; Roger, V.L.; Melton, L.J.; Bergstralh, E.J.; Li, X.; Peyser, P.A.; Krambeck, A.E.; Lieske, J.C. Kidney Stones Associate with Increased Risk for Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1641–1644.

- Eisner, B.H.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Kahn, A.J.; Stone, K.L.; Stoller, M.L. Nephrolithiasis and The Risk of Heart Disease in Older Women. J. Urol. 2009, 181, 517–518.

- Li, C.; Engström, G.; Hedblad, B.; Berglund, G.; Janzon, L. Risk Factors for Stroke in Subjects with Normal Blood Pressure: A Prospective Cohort Study. Stroke 2005, 36, 234–238.

- Westlund, K. Urolithiasis and Coronary Heart Disease: A Note on Association. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1973, 97, 167–172.

- Ljunghall, S.; Hedstrand, H. Renal Stones and Coronary Heart Disease. Acta Med. Scand. 1976, 199, 481–485.

- Ando, R.; Nagaya, T.; Suzuki, S.; Takahashi, H.; Kawai, M.; Okada, A.; Yasui, T.; Kubota, Y.; Umemoto, Y.; Tozawa, K.; et al. Kidney Stone Formation Is Positively Associated with Conventional Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease in Japanese Men. J. Urol. 2013, 189, 1340–1346.

More