Henry II of Castile, also known as Henry of Trastámara, from the Latin “Tras Tamaris” (or beyond the Tambre River), King of Castile and León (1366–1367, 1369–1379) was the first king of the Trastámara Dynasty. In summary, it was a minor branch of the house of Burgundy (or an “Iberian extension” of it), with presence in the kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, Navarre, and Naples. Most notably, it began playing an essential role in the kingdom of Castile, but after the Compromise of Caspe, its power extended decisively to the kingdom of Aragon (1412). Henry II was the illegitimate son of Alfonso XI and his lover Leonor de Guzmán. He waged a civil war against his stepbrother, Peter I, legitimate heir to the throne, as the son of Alfonso XI and Maria of Portugal, Queen of Castile. Henry’s determination to be recognized as king led him to employ the arts in a campaign to discredit his stepbrother and tarnish his image, portraying himself as a defender of the faith with the right to rule. He built the Royal Chapel (1371) in the main church of Córdoba (today’s Mosque/Cathedral) for the burial of his father and grandfather, Ferdinand IV, in order to underscore his connection to the royal line, and refurbished the Puerta del Perdón (Gate of Forgiveness) in 1377, the main entrance to the church, for use as a dramatic stage for public events.

- royal images

- royal iconography

- king of Castile and Leon

- Henry II of Castile

1. Introduction

To understand Henry’s achievements, it is necessary to appreciate the calamitous economic situation that had arisen due to the demographic crisis wrought by the Black Death, compounded not only by the war of the Two Peters (Peter I of Castile and Peter IV of Aragon) but also a civil war between petristas (supporters of Peter I) and enriqueños (backers of Enrique; that is, Henry), which became one more episode in the Hundred Years War due to the involvement of France, whose support Henry secured; and England, which supported Peter, who had turned to the Prince of Wales for help. Henry II, Count of Trastámara, managed to rally the nobles against Peter I in 1366, thanks to support from France and the Crown of Aragon, in addition to a carefully crafted campaign to depict his stepbrother as a tyrant. It is necessary to emphasize that Henry II would indirectly play an essential role in European history since the support of Castile to France would be consummated in the battle of La Rochelle (1372), resulting in an extreme fiasco of the English navy against the Castilian, led by the admiral A. Bocanegra. This fact would mean the beginning of the end of the Hundred Years War and would mark the decline of the English interests in France.

If there is one truly revolutionary aspect of Henry II’s reign that must be highlighted, one with profound consequences related to the image that he projected of himself through the arts, it was how, despite being a bastard son, he still managed to take the throne thanks to the support of the nobility. He rewarded them with ample and generous mercedes, favors in the form of goods, income, and privileges (hence, his nickname ‘the King of Las Mercedes’) and to convince the kingdom of his reign’s legitimacy, despite having risen to power through bloodshed.

2. The Accusation of “Tyrant”

In March 1366, Henry and his troops invaded Castile, conquering Burgos, the seat of the kingdom, from which Peter fled. On April 5, he was crowned king of Castile in the Royal Monastery of Las Huelgas, a site that must have been well calculated, as numerous kings were buried in its church, thereby constituting a site that would serve to bolster the legitimacy of Henry’s coronation. Thus began what came to be called the “first reign of Henry II.”

The first time the term “evil tyrant, an enemy of God and his holy Mother Church” was used was to accuse Peter that same year, in a document Henry sent to the town council of Covarrubias. With this epithet, he alluded to Peter’s supposed abuses in the exercise of power, and the injustices that he had perpetrated, which, according to the Trastámara camp, deprived Peter of any right to be king. This stance flouted the Castilian political tradition, which had always held that, as the king’s power came from God, even if he erred in his judgments, he had to be obeyed [5].

The idea that the king’s legitimacy depended on his upstanding behavior was spread under Henry thanks mainly to the chronicler Pedro López de Ayala, who propagated the idea:

“He who governs and defends his people well

This is a true king, may the other be removed” [6,7].

In addition, a factor in spreading Peter’s negative image was his vassals’ discontent with the high taxes they had to pay under him, in addition to the monarch’s reputation as a cruel leader, which led many to take refuge in other kingdoms for fear of being executed; his detractors dubbed him ‘the Cruel’ beginning in 1366, while his followers knew him as ‘the Just’.

The first reign culminated with Henry’s triumphant entry into Seville in 1366, according to López de Ayala: “that party, though he arrived near the city very early in the morning it was not until past the nones that he reached his palace” [6] (pp. 448–449). Seville was the city in which Peter I had found unconditional support and in whose old fortress he had built his palace in 1364, with the spectacular facade of the Montería courtyard, a dramatic backdrop against which to stage his power, plus the sumptuous Hall of Ambassadors [8]. This “ceremonialization of political life”, in the words of Nieto Soria [9], was a process that the Trastámara continued with the first monarch of the lineage to ascend to the throne of Castile: that is, Henry II.

The exotic, lavish sight of the palatine rooms in the old Andalusian fortress in Seville, built by Peter in a style featuring multiple Andalusian (mudéjar) influences, thanks to the work of artists sent by the Nasrid Sultan Muhammad V of Granada, who were working on the Alhambra [10], must have made a deep impression on Henry (Regarding the relationship between Henry II with Muhammad V of Granada, it was not exactly “cordial”. There were also some periods of crisis or clashes), who chose the city of Córdoba to produce a series of works whose primary objective was to demonstrate his legitimacy in the city that supported him. In this way, Seville and Córdoba reflect how that transition was visually produced from the last king of the House of Burgundy, Peter I, to the first of the Trastámara Dynasty, with Henry II using artistic forms as an essential vehicle to publicize this shift among the latter’s vassals. In this regard, Nieto Soria contrasts the idea of the ‘concealed king’ to that of the ‘exhibited king’, the latter being one who uses ceremonies calculated to achieve political purposes, vital in the case of the Trastámara Dynasty to justify its legitimacy and ensure loyalties to it [9] (pp. 51–72).

Another of the arguments used to seek Henry’s recognition was to depict him as a thoroughly Christian king, in contrast to Peter, who was portrayed as a defender of the Jews and a friend to the Muslims. As we pointed out, the economic crisis of the 14th century and the Black Death stirred up anti-Jewish sentiment among the population, who asked Henry to forgive debts contracted with Jewish moneylenders and to substantially limit the prerogatives that Peter I had granted them; the king’s treasurer had been the powerful Samuel Ha Leví, who ordered the construction of the great Synagogue of El Tránsito in Toledo. This would be one of the jewels of mudéjar art, a form of artistic expression that became a visual language shared by the three cultures existing on the Peninsula at that time (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism), despite the tensions between them at different times, as we have just noted.

The harmonious relationship between Peter I and Muhammad V of Granada is well known, as Peter helped the sultan to regain the throne, such that he was later able to count on aid from Nasrid troops in his struggle with his stepbrother. Peter’s tolerance towards Muslims and the fact that he received assistance from them in his confrontations with his stepbrother was also boldly used by his enemies to malign Peter as a protector of Christianity’s enemies. In fact, Henry even referred to the war against his stepbrother as a “crusade” [3] (p. 88). A letter to the Council of Covarrubias issued by the Trastámara chancellery in April 1366 states that the Castilian king was “supporting and enriching the Moors and the Jews, teaching them, and undercutting the Catholic faith” [11]. Despite the fact that Henry started out spurning these two minorities, he soon realized that he could not do without them and altered his position. This was visually represented through art, as we will see in two of his most emblematic artistic projects: the Royal Chapel and, especially, the Puerta del Perdón (Door of Forgiveness), both at the Cathedral of Córdoba, where Christian elements are fused with others of Islamic origin, with even the use of praise for God being in Arabic and also in Latin.

3. “I Neither Topple nor Install a King”

After Peter I’s defeat at the first Battle of Nájera, he obtained the support of the heir to the crown of England, the Prince of Wales, known as the Black Prince. On April 3, 1367, the armies of the two sides—petristas and enriquistas—clashed again in Nájera, where the latter were defeated, and Henry II losing the throne. Taken prisoner, among others, was the Breton commander Bertrand du Guesclin, a leader of the Free Companies, made up of mercenaries in the service of France, and later of Trastámara. Henry took refuge in France, where he reorganized his army to return definitively, this time with the support of numerous towns and bands disgruntled with Peter’s policies. In addition to working against Peter were the effects of propaganda tarnishing his image and rendering him unpopular [12].

In March 1369, the Trastámara side emerged triumphant at Montiel, where the famous fratricide took place on the night of the 22nd: when Peter was summoned to his stepbrother’s tent, a fight broke out, and Roger du Guesclin ended up slaying Peter. According to the tradition, when the Breton stabbed the king with his dagger, he uttered the celebrated phrase: “I neither topple nor install a king, I only help my lord” [13]. The regicide was, in Valdaliso’s words, presented as a tyrannicide, based on legitimizing arguments such as providentialism, with Henry claiming that he had been designated by God to put an end to Peter’s tyranny [14]. However, as this was not enough, other forms of justification were sought, such as his dynastic connection with his father, Alfonso XI, and it is here that the construction of the Royal Chapel in the Cathedral of Córdoba in 1371 for the burial of his grandfather and father, Fernando IV and Alfonso XI, takes on relevance. Upon Alfonso XI’s death in 1350 his lover, Leonor de Guzmán, had made plans for the marriage between her son Henry and Juana Manuel.

3.1. The Virgin of Tobed: A Dynastic Ex-Voto

The role of Leonor de Guzmán, Alfonso XI’s lover and Henry II’s mother, was decisive in giving her son the courage to aspire to the throne, and it was she who orchestrated a strategic link between him, her eldest son, and Juana Manuel, a great-granddaughter of Ferdinand III, the king who had wrested Cordoba from the Muslims in 1236. She was the daughter of the famous writer and powerful enfante Don Juan Manuel, such that this relationship was politically advantageous.

The work entitled The Virgen of Tobed, found at the Prado Museum since 2013 thanks to an important donation by the José Luis Várez Fisa collection to the Spanish art gallery, is a panel painted in tempera (161.4 × 117.8 cm) attributed to the painter Jaime Serra. Dating it has been a challenge, with the most recent studies placing it between 1367 and 1369, dates endorsed by Chao, and 1375, according to Borrás Gualis [15,16]. This work was the central panel of the main altarpiece of the church of Santa María de Tobed, an interesting mudéjar church/fortress erected in the municipality of Tobed (Zaragoza province). The altarpiece was a royal commission that takes on special relevance due to the portrayal of the donors at the Virgin’s feet: Henry II, with the inscription Enrico rege; his wife Juana Manuel de Villena, and their children Don Juan (the future John I of Castile, who would marry Eleanor of Aragon, the daughter of Peter IV the Ceremonious) and Eleanor of Castile, the future queen of Navarre by her marriage to Charles III the Noble.

The work, studied by numerous specialists (Due to the abundance of works on this work, we refer the reader to the most recent publication, where he will find updated bibliographic references: [15] (pp. 89–118), has been interpreted as an instrument designed to legitimize the Trastámara Dynasty through its strong symbolism. On a golden background, alluding to paradise, and under a lobed arch in whose spandrels, we see the coat of arms of Juana Manuel and the royal ones of Castile y León, in this order, revealing the importance attached to the queen’s lineage are four angels adoring the central figure, the Virgin Mary, who breastfeeds the Child while sitting on a cushion, following the model of the Virgin of Humility. They both stare at the viewer, but Maria’s sad gaze portends her son’s Passion and death. Everything in it transmits the luxury and splendor of the court: the red and blue mantle of the Virgin with motifs of facing birds, inspired by oriental fabrics; the lavish cushion whose minute patterns are inspired by the Islamic tradition’s sumptuous lusterware, the luxurious rug, and regal attire. The elegance and delicacy of its forms, as well as the exquisite details and the richness of its colors reveal the influence of 14th century Siena art on the artists of the Crown of Aragon, the Serra brothers included.

At the foot of Mary and the Child, on a significantly smaller scale, to recognize a hierarchy, the characters mentioned above appear as donors, all of them wearing the royal crown. To the right of the Virgin are the two men, in a position of privilege, and to her left, the women. In front of them on the ground are two helmets bearing the royal coat of arms and crest. Kneeling, they direct their prayers to Mary and Jesus, hence, the votive character that has been attributed to this work.

The fact that the four donors are crowned prompts Professor Borrás to date the work to the year 1375, as Henry II signed separate peace treaties with the King of Navarre (1373) and the King of Aragon (1375), strengthened by a strategically designed set of marriages [16] (pp. 169–175). Chao, however, argues that although the betrothals had taken place before 1375, by this year, neither of the two enfantes had yet married, the scholar noting that, in addition, they are still almost childlike in appearance (Figure 1) [15] (pp. 89–118).

2. The Accusation of “Tyrant”

“He who governs and defends his people wellThis is a true king, may the other be removed”.3. “I Neither Topple nor Install a King”

After Peter I’s defeat at the first Battle of Nájera, he obtained the support of the heir to the crown of England, the Prince of Wales, known as the Black Prince. On 3 April 1367, the armies of the two sides—petristas and enriquistas—clashed again in Nájera, where the latter were defeated, and Henry II losing the throne. Taken prisoner, among others, was the Breton commander Bertrand du Guesclin, a leader of the Free Companies, made up of mercenaries in the service of France, and later of Trastámara. Henry took refuge in France, where he reorganized his army to return definitively, this time with the support of numerous towns and bands disgruntled with Peter’s policies. In addition to working against Peter were the effects of propaganda tarnishing his image and rendering him unpopular [12]. In March 1369, the Trastámara side emerged triumphant at Montiel, where the famous fratricide took place on the night of the 22nd: when Peter was summoned to his stepbrother’s tent, a fight broke out, and Roger du Guesclin ended up slaying Peter. According to the tradition, when the Breton stabbed the king with his dagger, he uttered the celebrated phrase: “I neither topple nor install a king, I only help my lord” [13]. The regicide was, in Valdaliso’s words, presented as a tyrannicide, based on legitimizing arguments such as providentialism, with Henry claiming that he had been designated by God to put an end to Peter’s tyranny [14]. However, as this was not enough, other forms of justification were sought, such as his dynastic connection with his father, Alfonso XI, and it is here that the construction of the Royal Chapel in the Cathedral of Córdoba in 1371 for the burial of his grandfather and father, Fernando IV and Alfonso XI, takes on relevance. Upon Alfonso XI’s death in 1350 his lover, Leonor de Guzmán, had made plans for the marriage between her son Henry and Juana Manuel.The Virgin of Tobed: A Dynastic Ex-Voto

The role of Leonor de Guzmán, Alfonso XI’s lover and Henry II’s mother, was decisive in giving her son the courage to aspire to the throne, and it was she who orchestrated a strategic link between him, her eldest son, and Juana Manuel, a great-granddaughter of Ferdinand III, the king who had wrested Cordoba from the Muslims in 1236. She was the daughter of the famous writer and powerful enfante Don Juan Manuel, such that this relationship was politically advantageous.

Figure 1.

4. Spaces of Power and Legitimation in Córdoba’s Main Church

The Royal Chapel

The Virgin of Tobed with donors Henry II of Castile, his wife Juana Manuel, and two of their children. Painting. 1367–1369/1375. Attributed to Jaume Serra. Prado Museum. © Image Bank of the Prado Museum.

Special attention should be paid to the location of the heraldic symbols, unusual in that the crest of Juana Manuel, heiress to the Manuel family line, appears in a central position, breaking with heraldic tradition. This variation was intentional, to underscore the legitimacy of the lineage, as the queen was, on her paternal line, the granddaughter of the infante Manuel, the great-granddaughter of Ferdinand III of Castile, the Saint; and, on her maternal line, a granddaughter of the enfante Ferdinand de la Cerda, and a great-granddaughter of Alfonso X of Castile, the Wise. The problem that arose in the succession to the throne when Ferdinand died prematurely is known, his descendants being barred from ascending when the king’s brother Sancho IV was proclaimed king. As Chao points out, the prominence of the Manuel line’s coat of arms in the Tobed altarpiece, and the conspicuous absence of heraldic symbols corresponding to the la Cerda line, ancestors of Juana Manuel, could be due to the queen’s attempt to endow Henry II’s reign with greater legitimacy through her own connection, via her paternal line, to Ferdinand III, the Saint, the grandfather of her father Don Juan Manuel [15] (pp. 89–118).

Concurring with Borrás, the scene also includes a military legitimation of the Trastámara line based on the conquest of the kingdom of Castile and León after defeating Peter I, with Henry II and his son John in military attire, kneeling in prayer after having placed their helmets at the feet of the sacred figures, as an offering, in our view [16] (p. 174). This posture of submission and respect before God descends, as is known, from the Byzantine proskinesis, with remote origins in Persian ceremonies, an attitude that the emperors demonstrated by bestowing offerings seeking, in turn, divine recognition as worthy Christian rulers. Since the mantlets bear the coat of arms of Castile and León, and the four earthly figures appear wearing their respective crowns, it could be interpreted as a bold image in which the Trastámaras offer the Virgin and Child the union of the Christian kingdoms on the Peninsula, seeking Mary’s legitimation and blessing of those who were to sustain the dynasty, John I and Eleanor of Aragon, who also appear crowned. In line with the unity of the kingdoms under Christendom, we must not forget that the pope had recognized Henry II’s cause as a crusade, the latter setting out to achieve said unity through a series of advantageous marriages for his offspring, such as, for example, a frustrated attempt at an alliance with Portugal through John I’s marriage to Beatrice of Portugal, the daughter of said country’s King Ferdinand I.

4. Spaces of Power and Legitimation in Córdoba’s Main Church

Henry II did not construct a palace in Córdoba like what Peter I had constructed at the Reales Alcázares in Seville. There was already a royal alcázar, or fortress/palace, erected in Córdoba by his father Alfonso XI in 1328. Perhaps his efforts focused on the cathedral—the old main mosque—due to its obvious symbolic importance. Ferdinand III the Saint had taken the city from the Muslims in 1236, and the old mosque was converted into a main church and preserved as a symbol of his victory. The Trastámara wished to proclaim the new dynasty’s triumph by endowing this magnificent space with two very significant works, the Royal Chapel and the Puerta del Perdón (Forgiveness Gate).

4.1. The Royal Chapel

Henry II took advantage of the support that most of Córdoba’s nobility had offered him against his stepbrother, as well as the symbolic importance of this city as the former capital of the Umayyad Caliphate of Al Andalus, to stage his accession to the throne and leave an indelible visual mark of his reign as a legacy for eternity. Without a doubt, his most important artistic undertaking was the Royal Chapel in the main church of Córdoba (the Mosque/Cathedral).

According to the inscription on this chapel, it was completed in 1371 (For this study we rely on previously conducted research, to which we refer for more information: [17]), [18,19], (It has also been a subject of interest, more recently, for [20]) (We must highlight the works of Nogales Rincón, especially his doctoral thesis: [21]). Henry II had the bodies of his grandfather, Ferdinand IV of Castile, the Summoned; and his father Alfonso XI, transferred there. Ferdinand IV was already buried in Cordoba, but Alfonso XI was in the Royal Chapel of the Cathedral of Seville (along with Fernando III and Alfonso X). Apparently, above the aforementioned inscription, there hung a portrait of Henry II himself, thereby rounding out the message of legitimation. To this must be added the location of the chapel just behind the old clerestory of Caliph al-Hakam II, reused by the Christians as a main chapel after the conquest until the 16th century, dedicating it to Our Lady of Villaviciosa. In the latter, there was a series of images exalting the apostles Peter and Paul (the city was conquered on June 29, these saints’ feast day), a frieze representing kings and saints, and a gallery of kings and saints that ran around the upper part of the walls; Professor Laguna Paúl has ascribed them to the painter Alonso Martínez and dated them to 1351, under the reign of Peter I [22]. Today, we only have a Latin inscription and two fragments identified as belonging to Christ and the Virgin, preserved at the Museum of Fine Arts. The aforementioned inscription reads: “[In the name of the Glorious Trinity] the mighty Father and Son and Holy Spirit the very noble King Ferdinand won the very noble city of [Cordoba]”. According to Romero Barros, it was completed with the name of Alfonso X, the son of the holy king, and the date of the city’s conquest [23].

Even more interesting for the purposes of this study is that, on the west wall of the Royal Chapel, R. Ramírez de Arellano and Mateo Inurria discovered, in three niches, evidence of paintings of three kings placed there, presumably the portraits of Henry II, in the center, flanked by Alfonso XI, his father, and Ferdinand IV, his grandfather [24]. That of Henry II was, apparently, just above the founding inscription, which read: “This is the very great king, Henry, who, to honor the body of the king, his father, had this chapel built in MCCCLXXI”, that is, in 1371.

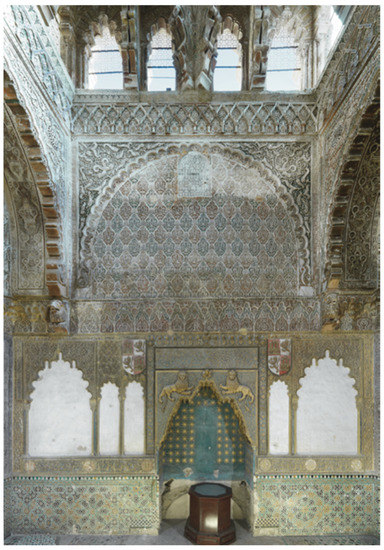

On the east wall of the chapel, there is a niche framed by a pavilion arch full of muqarnas (honeycomb vaulting) and polychrome with gold leaf. The niche’s background is blue, dotted with golden stars, and in the center, there must have been an image, originally on the altar table. This image was replaced by a sculpture of Ferdinand III, the Saint, canonized in 1671. The original figure may have also been that of this king, as the alcove is flanked by the shields of Castile and León, with two superb lions rampant crowned in relief guarding it. In addition, the plasterwork frieze that tops the tiled plinth features, alternately, the emblems of Castile and León, along with the inscription ‘happiness’ in Kufic Arabic (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

5. The Majestic Image of the King: Sigillography and Numismatics

5.1. Sigillography

Royal Chapel’s East wall. 1371. Mosque/Cathedral of Córdoba.

There is no doubt as to Henry II’s aim to erect this chapel within the city’s most important church to portray himself as a descendant of the kings extending back to Ferdinand III, who had managed to recover Córdoba for Christendom after five centuries under Islamic rule. The ensemble formed by the main chapel and the adjoining Royal Chapel, conceived as interconnected spaces, constituted a material manifestation, an offering to God signifying those feats, a memento regum to reach paradise, with these monarchs, who had been appointed by divine grace to rule, thus providing an account of themselves (On the meaning of the royal chapels of the late Trastamara Dynasty, see [9] (pp. 67–68)). The last years of his reign were marked by policies that sought to pacify the different kingdoms and to integrate Portugal [25]. The king died in 1379 and his son, John I, married Beatrice, the daughter of Portugal’s King Ferdinand I, in 1383 [26].

5. The Majestic Image of the King: Sigillography and Numismatics

5.1. Sigillography

The lead seals preserved from the stage of Henry II prior to the events of Montiel represent him on the front under the traditional equestrian image, as Peter I had done, but it is striking how, after the fratricide and the definitive ascent of the Trastámaras to the throne, the new seals—of lead and measuring 51 mm in diameter—depicted him in a majestic manner, seated upon two lions alluding to the Solomonic throne in order to manifest the king’s authority to impart justice (Figure 3). His claim to succession was, thus, reaffirmed, as in the imago maiestatis the iura regalia are represented; that is, the most common symbols of power: a sword in his right hand, a crown and orb in his left, transmitting a sense of continuity along the dynastic line, and of legitimacy. The presence of the cross on the globe and the crown reiterates the idea of the king as Christ’s envoy, while the fleur-de-lis topping the pommel of the sword reveals a French influence. On the reverse appear the heraldic arms of Castile and León. A fleur-de-lis cross creates the checkered pattern in which the castles and crowned rampant lions are alternately inserted. On the borders of both sides, we read the inscription: “† S : ENRICI : DEI : GRACIA : REGIS : CASTELLE : ET : LEGIONIS” [27].

(3

a)

(

b)

5.2. Numismatics

Figure 34. Seal of Henry II. Impression on lead. 1371. Archivo Municipal de Toledo. © Archivo Municipal, Toledo, Spain: (

a

b) Back (The original document dates from 16 September, 1371, and is stored in the Archivo Municipal of Toledo (Spain), Secret Archive, Drawer 10, File 6, Number 6, Piece 3. See [28]).

5.2. Numismatics.

The first coins minted by Henry II were gold doblas featuring the image of the crowned king on a galloping horse and brandishing a sword on the front, and the crest of Castile and León on the back. This figuration corresponded to the concept of the medieval knight, as a Miles Christi, or soldier of Christ, defending the faith, but as the war depleted the coffers and it became imperative to sully the image of his eternal nemesis, Peter I, the currency evolved, losing value and favoring the idea of a pious king rather than a bellicose one.

According to Fuentes Ganzo, in the civil war, Peter I incurred serious debts when he had to hire Duguesclin’s mercenary troops, a dilemma compounded by the devaluation of the currency. As of 1366, when the civil war began, reales de vellón coins, imitating silver, constituted a “formidable official forgery” [29]. Starting in 1369, when the war ended, a new coin was minted with a substantial change in its propagandistic objective, the old anagram being replaced with a crowned bust of Henry II, facing left on the front, and a cross occupying the entire back, thus projecting an image of the king as a Christian knight in contrast to his stepbrother Peter I, depicted as a cruel defender of the infidels.

The Archaeological Museum of Córdoba, which boats an extraordinary numismatic collection, houses several coins from the period of Henry II. Among them, the best preserved is a vellón coin produced at the Segovia mint, possibly after 1373 (Figure 4) Module: 180 cm. Thickness: 0.5 mm. Weight: 0.85 gr.

6. Conclusions

Henry II of Castile, also known as Henry of Trastámara, the illegitimate son of King Alfonso XI and his lover Leonor de Guzmán, managed to ascend to the throne after the murder of his half-brother Peter I, the legitimate heir and king of Castile and León. Peter’s death being under suspicious circumstances, pointing to Henry as the agent behind it—if not materially, as an instigator of this bloody event—spurred Peter’s followers to insistently question Henry’s legitimacy. Hence, in order to be recognized as the rightful new king, Henry engaged in a smear campaign against his stepbrother, both while he was alive and even after his death, accusing him of being a bad Christian, citing his support for Muslims and Jews, while upholding the House of Trastámara, in contrast, as a defender of the faith in a genuine crusade that he and the pope himself recognized. It is in this context that the artistic initiatives sponsored by this king must be viewed, such as the famous panel of the Virgin of Tobed, conceived as a dynastic ex-voto to portray Henry as a staunch defender of Christianity, thereby winning him supporters. In Córdoba, a city that supported him in his rise to the throne, he backed the construction of the Royal Chapel in the Mosque-Cathedral, where his portrait was found, and today, a foundational inscription remains. This chapel was conceived for the burial of his grandfather, Ferdinando IV, and his father, Alfonso XI. The work was, again, conceived to reinforce Henry’s claims to dynastic legitimacy, with this being further bolstered through another one found at this monumental complex: the Puerta del Perdón, or Gate of Forgiveness, where he arranged heraldic shields and inscriptions stressing his legitimacy and defense of Christianity.

The lead seals during the initial stage of Henry II’s reign present a standard equestrian image, but after the fratricide, they feature a more majestic depiction of the king, in full royal regalia: sword, crown, and orb. On the coins, a similar change can be appreciated: after 1369, the old anagram was dispensed with, replaced by a bust of a crowned Henry, and on the back was the cross, emphasizing the king’s piety. In this way, Henry used his self-image to promote his claim as the rightful king of Castile.

6. Conclusions

References

- Valdeón Baruque, J. Las crisis del siglo XV. In Homenaje a Marcelo Vigil Pascual: La Historia en el Contexto de las Ciencias Humanas y Sociales; Hidalgo de la Vega, M.J., Ed.; Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 1989; pp. 217–235.

- Cerda y Rico, F. (Ed.) Crónica de Don Alfonso el Onceno; Imprenta de D. Antonio de Sancha: Madrid, Spain, 1787; Part 1, Chapter XCIII; p. 166.

- Valdeón Baruque, J. Enrique II (1369–1379); Diputación Provincial de Palencia, Ed.; La Olmeda: Palencia, Spain, 1996.

- López de Ayala, P. Crónicas de los reyes de Castilla, Pedro I, Enrique II, Juan I y Enrique III; Editorial el Progreso: Madrid, Spain, 1953.

- Valdeón Baruque, J. La propaganda ideológica, arma de combate de Enrique de Trastamara (1366–1369). Historia Instituciones, Documentos 1992, 19, 459–467.

- López de Ayala, P. Rimado de Palacio. In Poetas Castellanos Anteriores al Siglo XV; Biblioteca de Autores Españoles: Madrid, Spain, 1952; p. 432.

- Pastor Cuevas, M.C. Principios políticos en la Crónica de Pedro I de Pedro López de Ayala. In Actes del VII Congrés de l’Associació Hispánica de Literatura Medieval; Universitat Jaume I: Castellón de la Plana, Spain, 1999; Volume 3, pp. 133–143.

- Almagro Gorbea, A.; Zúñiga Urbano, J.A.; González Garrido, M.; Rodríguez, C.; Garrido Carretero, F.; Almagro-Vidal, A. El Alcázar de Sevilla en el siglo XIV; CSIC, Escuela de Estudios Árabes: Granada, Spain, 2014.

- Nieto Soria, J.M. Ceremonia y pompa para una monarquía: Los Trastámara de Castilla. Cuadernos del CERyM 2009, 17, 51–72.

- González Hernández, A. De nuevo sobre el palacio del rey don Pedro I en Tordesillas. Reales Sitios 2007, 171, 4–21.

- Serrano, L. Fuentes para la historia de Castilla, t. II. In Cartulario del Infantado de Covarrubias; Cuesta: Valladolid, Spain, 1907; p. 217.

- Valdeón Baruque, J. Enrique II. In Diccionario Biográfico Electrónico; Real Academia de la Historia; Available online: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/6635/enrique-ii (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Valdaliso Casanova, C. Fuentes para el estudio del reinado de Pedro I de Castilla: el relato de Lope García de Salazar en las Bienandanzas y Fortunas. Memorabilia 2011, 13, 253–283.

- Valdaliso Casanova, C. La legitimación dinástica en la dinastía Trastamara. Res Publica 2007, 18, 307–321.

- Chao Castro, D. Patronazgo regio en femenino: La Virgen de Tobed y el protagonismo legitimador de doña Juana Manuel de Villena para la dinastía Trastámara. In Entre el altar y la corte. Intercambios Sociales y Culturales Hispánicos (Siglos XIII-XV); Olivera Serrano, C., Ed.; Athenaica: Sevilla, Spain, 2021; pp. 89–118.

- Borrás Gualis, G.M. La Virgen de Tobed. Exvoto dinástico de los Trastámara. In Miscelánea de Estudios en Homenaje a Guillermo Fatás Cabeza; Escribano Paño, M.V., Duplá Ansuátegui, A., Sancho Rocher, L., Villacampa Rubio, M.A., Eds.; Institución Fernando el Católico, Diputación de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2014; pp. 169–175.

- Jordano Barbudo, M.Á. El mudéjar en Córdoba; Diputación de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2002; pp. 117–129.

- Idem. A “floral dress” for the garden of paradise. Mirabilia 2011, 12, 91–104.

- Idem. La Capilla Real de la Catedral de Córdoba y su repercusión en las fundaciones nobiliarias durante la Baja Edad Media. Mirabilia 2009, 9, 156–176.

- Abad Castro, C.; González Cavero, I. La Capilla Real de la Catedral de Córdoba. Some hypotheses about its royal patronage and construction process. Anuario de Estudios Medievales 2019, 49, 393–426.

- Nogales Rincón, D. La representación religiosa de la monarquía castellano-leonesa. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2009.

- Laguna Paúl, T. Dos fragmentos en busca de autor y una fecha equívoca. Alonso Martínez, pintor en Córdoba a mediados del siglo XIV, y las pinturas de la capilla de Villaviciosa. Laboratorio de Arte 2005, 18, 73–88.

- Romero Barros, R.; Romero de Torres, R.; Mudarra Barrero, M. Córdoba monumental y artística; Junta de Andalucía: Córdoba, Spain, 1991; fol. 116.

- Ramírez de Arellano y Gutiérrez, R. Inventario Monumental y Artístico de la Provincia de Córdoba; Monte de Piedad y Caja de Ahorros: Córdoba, Spain, 1982; pp. 59–60.

- Pascual Martínez, L. Itinerario andaluz de Enrique II de Castilla. In Actas del I Congreso de Historia de Andalucía, Andalucía Medieval; Cajasur: Córdoba, Spain, 1976; Volume 2, pp. 203–204.

- Molinero Merchán, J.A. La Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba: Símbolos de poder. Estudio histórico-artístico a través de sus armerías; Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2005; pp. 188–194.

- Chao Castro, D. Imágenes de poder de los reyes Trastámara de Castilla: el rey y la representación de su imago maiestatis en la sigilografía, la numismática y la miniatura. e-Spania 2007, 3. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/e-spania/15253 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- García Ruipérez, M.; Galende Díaz, J.C. Los sellos pendientes en el Archivo Municipal de Toledo. In De sellos y blasones; Galende Díaz, J.C., Ávila Seoane, N., Eds.; Universidad Complutense: Madrid, Spain, 2012; pp. 255–292.

- Fuentes Ganzo, E. El cruzado de vellón de Enrique II y el cruzado de frontera. Tipos y cecas (1369–1373). Hecate 2019, 6, 136–163.