King Stefan Uroš II Milutin Nemanjić (1282—Donje Nerodimlje, October 29, 1321) was a Serbian medieval king, the seventh ruler of the Serbian Nemanide dynasty, the son of King Stefan Uroš I (r. 1243–1276) and Queen Helen Nemanjić (see), the brother of the King Stefan Dragutin (r. 1276–1282) and the father of King Stefan Dečanski (r. 1322–1331). Together with his great grandfather Stefan Nemanja, the founder of the Nemanide dynasty, and his grandson, Emperor Stefan Uroš IV Dušan, King Milutin is considered the most powerful ruler of the Nemanide dynasty. The long and successful military breach of King Milutin, down the Vardar River Valley and deep into the Byzantine territories, represents the beginning of Serbian expansion into southeastern Europe, making it the dominant political power in the Balkan region in the 14th century. During that period, Serbian economic power grew rapidly, mostly because of the development of trading and mining. King Milutin founded Novo Brdo, an internationally important silver mining site. He started minting his own money, producing imitations of Venetian coins (grosso), which gradually diminished in value. This led to the ban of these coins by the Republic of Venice and provided King Milutin a place in Dante’s Divina Commedia. King Milutin had a specific philoktesia fervor: He built or renovated over three dozen Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries not only in Serbia but also in Thessaloniki, Mt. Athos, Constantinople and The Holy Land. Over fifteen of his portraits can be found in the monumental painting ensembles of Serbian medieval monasteries as well as on two icons.

1. Introduction

King Stefan Uroš II Milutin Nemanjić was born around 1254–1255

[1] (p. 53) as the second son of King Uroš I Nemanjić (r. 1243–1276) and Queen Helen. According to the newest research, besides elder brother Dragutin and sister Brnj(a)ča, King Milutin probably had another elder brother, Stefan, who passed away as a child and was buried in the catholicon’s nave of Studenica Monastery

[2] (p. 94). The life of the young prince Milutin—before his ascension to the throne of Serbia in 1282—is not very well known because of the almost total lack of Serbian historical sources of that time. According to

Lives of Serbian Kings and Archbishops by his contemporary Archbishop Danilo II, a conflict broke out between his father King Uroš I and his brother King Stefan Uroš Dragutin in 1276. King Uroš I abdicated and died less than 2 years later in the region of Hum. Six years later, following a riding accident, King Dragutin abdicated in favor of his younger brother during the council of Deževo (1282). Recently, these biographical facts were questioned by Vlada Stanković, who assumes that instead of the common belief about the reign of Dragutin from 1276 to 1282 and the subsequent first reign of Milutin till 1299, there was a “peculiar (ruling) collegium” of Kings Dragutin and Milutin, and their mother Queen Helen that lasted from the abdication of the King Uroš I in 1276 to the peace agreement with Byzantines in 1299

[1] (p. 69). Their mutual appearance proves this assumption in the fresco ensembles of the churches in monasteries of Gradac, Đurdjevi Stupovi and Arilje, as well on the two icons and the founder’s inscription of the restored Benedictine abbey of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus near Shkodër on the Boyana River

[3] (p. 97).

It is a very well-known fact that several marriages of King Milutin made him a strong opposition both of Serbian Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches. However exaggerated in number, the marriage alliances of King Milutin were part of overall changes in Serbian politics during the second half of the 13th century and the very complex political relations that Serbia had with Byzantium, Hungary and Bulgary of that period

[1] (p. 53). Although the final list of Milutin’s spouses is still to be established, some recent researchers have proposed Milutin’s marriage curriculum. According to common knowledge, King Milutin’s first wife was a certain Serbian noblewoman who identified with Jelena (Helen) and whom King Milutin, after a certain time, expelled “for no reason and against her will”

[4] (p. 58). After that episode, and in the changing political environment, Milutin married the daughter of sebastokrator John II Angelos, ruler of Thessaly

[1] (p. 48). When King Stefan Dragutin dethroned their father Stefan Uroš I in 1276, Milutin married (previously Catholic nun) Elisabeth, the sister of his brother’s wife Catherine who, after another political turmoil and the end of their marriage at an unknown date, returned to Hungary. According to some documents still preserved in the Archives of Dubrovnik, King Milutin remarried again in 1284, this time to the daughter of the Bulgarian tsar George Terter, Anna

[1] (p. 67). In 1298, as a result of a huge Byzantine military defeat, Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos promised a marriage alliance of his 5-year-old daughter Symonis to the Serbian ruler King Milutin

[1] (pp. 94–106). The Orthodox Diocese in Constantinople opposed the marriage because of the king’s previous marriages and the vast age difference, but the Byzantine Emperor was determined to do so. In late 1298, he sent his trusted minister Theodore Metochites to Serbia to conduct the negotiations. On his part, King Milutin too was eager to accept this marriage and divorced his wife, Anna Terter. Princess Symonis and King Milutin’s marriage was celebrated in Thessalonica in the springtime of 1299, and the couple departed for Serbia

[5] (p. 457). As a wedding present, Byzantines recognized Serbian rule north of the line Ohrid—Prilep—Štip. King Milutin became a son-in-law of the actual Byzantine Emperor, which triggered an overall Byzantinization of Serbian society

[6]. Just after a peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire was signed in 1299, disputes began between Milutin and his brother Stefan Dragutin. War broke out between the brothers and lasted, with sporadic cease-fires, until Dragutin’s death in 1314. By 1309, Milutin appointed his son, future king Stefan Uroš III Dečanski, as governor of Zeta (present-day Montenegro)

[7] (p. 176). This meant that Stefan Uroš III Dečanski was to become heir to the throne in Serbia and not Dragutin’s son Stefan Vladislav II as it was agreed at Deževo Council. King Stefan Uroš II Milutin died in Donje Nerodimlje on October 29, 1321. Barely 3 years after his death in 1321, King Milutin was proclaimed a saint, although he never took a monastic vow as all his ancestors on the throne of Serbia before him did. His feast day is celebrated on 30 October/12 November.

2. Church of the Holy Virgin Ljeviška, Prizren

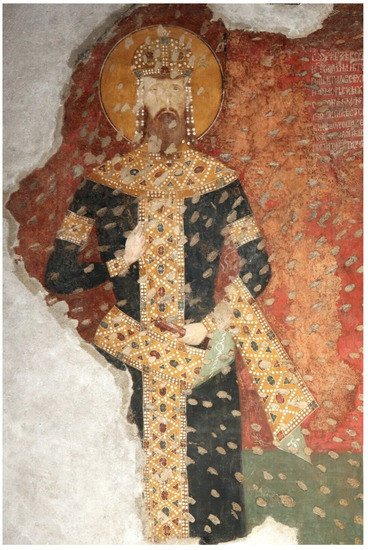

The Church of the Holy Virgin Ljeviška is located in Prizren (Kosovo), at the foot of mountain Šara and on the banks of the Bistrica River. From Antiquity, Prizren represented a crossroad of all-important trading routes which from the coastal regions branched toward Balkan inland and further toward Niš, Thessaloniki and Constantinople. After the defeat of Byzantium at the end of the 13th century, Prizren became part of the Serbian state. King Milutin decided to reconstruct Prizren cathedral—previously built early 6th century Byzantine basilica—and, following the demands of his time in 1306/07 [8] (p. 11), he ordered the reshaping of the Holy Virgin Ljeviška into a cross-in-square five dome church with the exonarthex and a high belfry. Inside the church, an extraordinary fresco ensemble is still partially preserved. Painter Astrapas, together with his associates and assistants, covered all surfaces of the interior walls, vaults and domes with frescos from around 1310 to 1313 [8] (p. 43). On the north side of the east wall of the narthex of the church, on the ceremonial red background, King Milutin is represented with a brown beard holding a cross in his right hand blessed by Christ, represented as a semi-figure above the entrance into the nave. It is a colossal, 2.55 m-high figure dressed in full Byzantine Imperial costume with the crown on his head and the long inscription that reads: “in Christ, the God faithful, despot and of holy birth, and pious Stefan Uroš, king of all Serbian lands and Littoral, great-grandson of Saint Symeon Nemanja, grandson of the the First-Crowned King Stefan, son-in-law of the great Greek Emperor Palaiologos Kyr Andronikos and the endower of this holy place” (Figure 1). The purpose of the painting was to confirm and highlight Milutin’s legitimacy on the throne of Serbia and his alliance with the ruling Byzantine Emperor. As a result, he was not depicted with the church in his arms, unlike the usual representation of ktetorship in the Serbian endowments.

Figure 1. King Milutin, fresco, 1310–1313. Holy Virgin Ljeviška church in Prizren, north side of the east wall of the narthex, Photo Vladimir Perić. Courtesy BLAGO Fund, Inc.

3. Ascension Church of the Žiča Monastery

Originally imagined as a burial place of the first Serbian King, Stefan the First-Crowned, the Ascension Church of the Žiča Monastery gradually changed its primary function and became the First Serbian Cathedral, a coronation church, and the seat of Archbishoprics of all Serbian lands from 1219 to 1253. Built not far from the confluence of the Ibar and the Morava rivers in a spacious natural valley surrounded by hills, well-connected by a network of communications, near the present-day town of Kraljevo, the cathedral church was not well protected from assaults. One of them, conducted by an unexpected and violent raid by Mongols, left the church, which was previously very nicely decorated, without a huge percentage of its frescoes. King Milutin renovated it from 1309 to 1316 [9] (p. 146), thus becoming its second donor. Presented above the portraits of Stefan the First-Crowned and his son and heir, Radoslav, directly above the entrance to the church, is the Christmas Hymn. The hymn represents the enthroned Virgin, with small Christ in her lap in the upper part of the scene (the iconography of which relies on the contents of Anatolios’ sticheron but is accompanied by the text of John Damascene’s verses), in the celebration of which Serbian King Milutin, dressed in imperial costume, and Archbishop Sava III are participating (Figure 2). For the first time within the religious composition, living people are shown. Two ceremonial processions, which the two of them are leading, are moving one toward each other in the lower part of the scene. The symmetry in the representation of the ruler and the leader of the Church, while they jointly celebrate God as the supreme Lord, expresses the notion of the harmony (symphonia) between the state and church authority on Earth. The place for presenting the Christmas Hymn in Žiča was not selected by chance. The entrance into the narthex of the main cathedral church was the place where, according to the rules of the Constantinople rite, the two processions met ahead of the liturgy, one led by the secular ruler and the other by the spiritual leader. By quoting this ceremony within a scene that refers to gifts and serving the God incarnate, the person who devised the composition in Žiča stressed the exalted aspect of the mission of the Serbian king and the archbishop. By carrying out this mission, according to Vojvodić, they both confirmed the Christian legitimacy of their dignity and, together with the whole of the universe, presented a worthy gift to the source of all powers [8] (p. 538).

Figure 2. King Milutin leading ceremonial procession within the scene of the Christmas Hymn (right), fresco, 1309–1316. Ascension Church of the Žiča Monastery, south side of the lunette above the entrance. Courtesy Gallery of Frescoes, Belgrade.

4. Monastery of Staro Nagoričino, Church of St. George Tropaioforos

Staro Nagoričane is the village in the Sredorek region of present-day North Macedonia and is famous for its 11th century three-nave basilica that was reconstructed during King Milutin’s reign into the cross-in-square five dome church. The interior decoration was likely done between 1317 and 1318 by Michael Astrapas, the leading artist of King Milutin’s court artistic workshop [10] (p. 104).

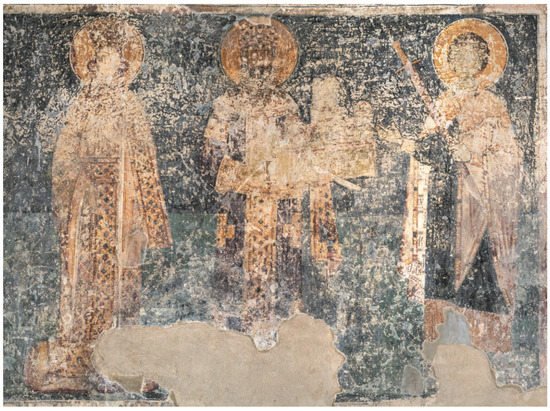

On the north wall of the narthex, King Milutin is represented holding the church and the scroll in his left hand and handing them to St. George signed Tropaioforos (The Victorious), who is represented on his left. The saint reciprocates King Milutin by offering him a sword as a kind of symbolic investiture (Figure 3). Behind King Milutun, on his right, Queen Symonis is represented in ceremonial attire. The scene lacks a representation of Christ to whom the king offers the church. King Milutin and Queen Symonis are depicted with the insignia of the Byzantine rulers as later in King’s church in Studenica Monastery followed by the representation of St. Constantin and St. Helen. According to Radojčić [11] (p. 35), all Serbian rulers who emphasized their family ties to the imperial court painted these very saints near their portraits.

Figure 3. King Milutin with the church, fresco, 1317–1318. Church of St. George Tropaioforos, Monastery of Staro Nagoričino, north wall of the narthex. Photo Bojan Popović.

5. King’s Church, Sts. Joachim and Anna, Studenica Monastery

According to the fully preserved inscription carved in the chapel’s apse’s exterior, King’s Church was built in 1314 within the complex of the Studenica Monastery at the slopes of Golija Mountain, 12 km from the town of Ušće, in the gorge of Studenica River.

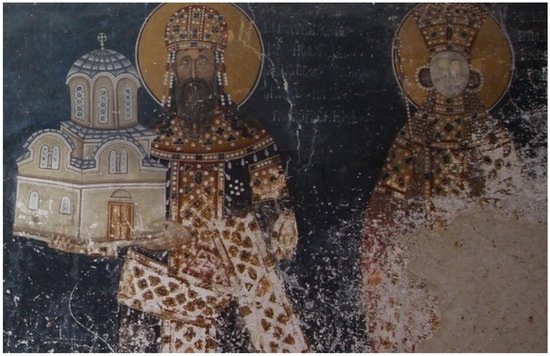

The interior of King’s church is one of the best examples of the paintings of the Palaiologan Renaissance on Serbian soil, done by Mihailo Astrapas and his workshop either in 1314 [10] (p. 104) or in 1318–1319 [12] (p. 439). It is very well preserved. The founder’s scene is placed, as usual, in the first zone of the south wall of the nave. It is a part of a larger scene that starts left of the ktetor, right next to the altar chancel, where Christ is represented, followed by his grandparents St. Joachim and St. Anne. St. Anne is holding little Mother of God in her arms. To the right of King Milutin, Queen Symonis is represented. Again, the representations of St. Constantin and Helen are painted next to her on the west wall. Inscriptions mentioning the king’s and Queen’s official titles are placed next to their heads and written in Serbian. King Milutin is depicted as an older man with a long beard and hair that falls on his shoulders wearing the insignia of the Byzantine rulers. He is dressed in a black imperial costume sakkos (σάκκος) with loros (λῶρος)—a wide decorated ribbon wound around the torso so that one end hung down in front and the other hung over the right arm, and a wide collar maniakion (μᾰνῐᾰ́κῐον) decorated with pearls and precious stones. On his head, he wears a Byzantine crown with orphanos (gem) and pearly prependulia (πρεπενδoύλια) while carrying his church in his hands. What catches the eye is the new color of the incarnate. Milutin’s face is pink (Figure 4) unlike the faces of the saints, which are blue-green. In the first zone of the opposite, north wall, just across the small nave of the church, St. Symeon and St. Sava are represented. The position of the church within the complex of the Studenica Monastery, its external similarity to the catholicon, the dedication of the church to St. Joachim and St. Anne, the representation of Christ’s genealogy on the chapel’s frescoes and their programmatic relation with the personalities of the King’s ancestors had a specific theological and ideological basis. They were conceived to stress the parallels between Christ’s (Sts. Joachim and Anne) and King Milutin’s (St. Symeon Nemanja) ancestors, i.e., between Christ and King Milutin himself [13] (pp. 191–195). The idea of ancestry, however, permeates the overall painted program of the King’s Church much more comprehensively [14] (pp. 187–191).

Figure 4. King Milutin carrying church and Queen Symonis, fresco, 1318–1319 King’s church, Sts. Joachim and Anne, Studenica Monastery, Courtesy BLAGO Fund, Inc.

6. Annunciation Church, Gračanica Monastery

The Annunciation Church of the Gračanica Monastery is one of the King Stefan Uroš II Milutin’s last monumental endowments. The monastery is located in Gračanica, Kosovo, about 5 km from Priština, and according to the charter painted on the western wall of the south parekklesion, it was decorated between 1318 and 1321 [15] (p. 74). It represents one of the chef-d’oeuvre of the Serbian and Byzantine art and architecture. The founder’s scene is placed on both sides of the arch separating the narthex from the nave. On the north side, King Milutin is now represented as an old man with long gray hair and a beard in Byzantine imperial attire, holding Gračanica with both his hands (Figure 5) while an angel with a crown descends from the sky toward him. Across from him is Queen Symonis, to whom an angel also lands a crown. In the vault is a representation of Christ blessing angels carrying the crowns. Iconographically, this representation is a combination of the founder’s portrait and symbolic investiture. This formula, which testified that the power of autocratic rulers came directly from God and that they were subordinate only to him, had a very long history in Byzantine art [16] (p. 312) and, for the first time in Serbian art, was introduced in Gračanica.

Figure 5. King Milutin with the church, fresco, 1321. Church of Annunciation, Monastery of Gračanica, northern part of the vault between the narthex and nave. Courtesy Gallery of Frescoes, Belgrade.

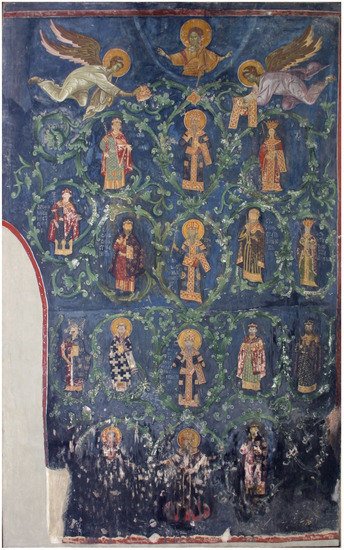

Nonetheless, the most interesting type of Serbian historical painting that appears in Gračanica for the first time is the so-called Nemanide Genealogical Tree (Figure 6). The fresco is located on the south part of the eastern wall of the narthex and measures about 1.75 m in wide and about 3.25 m in high. Sixteen portraits of Nemanide family members, arranged in four rows and entwined in an ivy vine, are represented. St. Stefan Nemanja, dressed in purple clothes with a halo, is in the center of the first row, representing the “good root” of the tree. In the central part of the second row, Stefan the First-crowned is presented in a divitision with a crown, scepter, and halo. In the third row, King Uroš I takes the central part, while the genealogical tree is crowned with King Milutin, surrounded by his daughter Tzariza and his son Constantine. They are all blessed by the Christ, who is placed above them, and flanked with angels that are landing the ruler’s insignia on King Milutin’s head. Stefan Dečanski, heir to the throne and later king, is not represented here as the fresco was created at the time of his exile. The side branches of each row are filled with Nemanides of the appropriate generation, including two female persons and two archbishops of Nemanide origin: St. Sava and Sava II [10] (pp. 38–39). The Nemanide Genealogical Tree represents a crucial iconographical step in the transformation of the horizontal line of Nemanides-monks into the vertical genealogical picture of Nemanide conceived after the model of Genealogical Tree of Jesse. The emphasis on the parallelism between the representatives of the Serbian holy dynasty and the biblical line of the righteous is not completely new and can be traced in Serbian monumental art since the second half of the 13th century, as in the narthex of Sopoćani and in Arilje [17] (pp. 111–113). However, the vertical genealogical tree was not a simple transposition of the horizontal genealogies into the structure of the new iconographic scheme. Between the two types of Serbian dynastic images, significant content differences are noticeable. Horizontal genealogy, for example, very often included representations of ruling consorts or ruling mothers (Queen Helen), while in the vertical one, they appear much later and only as an exception and for special reasons. As for the ruling sisters and daughters, the situation is completely reversed because, in the vertical genealogy, their characters were painted regularly under the condition that they were not “odive” i.e., married into other families [18] (p. 297).

Figure 6. Nemanide’s Genealogical Tree, fresco, 1321. Church of Annunciation, Monastery of Gračanica, south part of the eastern wall of the narthex. Courtesy Gallery of Frescoes, Belgrade.

7. Church of the Presentation of the Virgin, Monastery of Chilandar

The Church of the Presentation of the Virgin in Chilandar is the oldest endowment of the Nemanide dynasty outside Serbia, located on Mt. Athos in Greece. Founded by Stefan Nemanja, who died there as a monk Symeon in 1199, the present-day catholicon of the monastery was renewed at the beginning of the 14th century under King Milutin. The original church was remodeled to the cross-in-square triconchal domed construction with a two-domed narthex. Together with construction works, in 1321, King Milutin restored the damaged interior fresco decoration. His portraits appear twice in it. The first one is located in the southwest corner of the nave, near the original tomb of St. Symeon Nemanja (Figure 7). On it, Milutin is represented in full Byzantine Imperial costume with the crown on his head and with both hands raised in prayer. This last feature makes this portrait of Milutin very peculiar because, in his numerous other founder’s portraits, he always wears either insignia of his authority or holds a church. Here, even more unusual is the omission of the suppedion under the king’s feet, which can be found in almost all portraits of Serbian rulers from the time of King Dragutin to Milutin’s other founder’s portraits in the narthex of Chilandar. This iconographical idiosyncrasy can be explained by the proximity of King’s portrait to the former tomb of Stefan Nemanja, from which he “sprouted like from the good root” [19] (p. 250).

Figure 7. King Milutin fresco, 1321. Church of the Presentation of the Virgin, Monastery of Chilandar, southwest corner of the nave. Courtesy Gallery of Frescoes, Belgrade.

The second portrait of King Milutin is located on the southern part of the second zone of the east wall of the narthex (Figure 8). The center of the composition consists of the representation of the Virgin Mary with a small Christ in her lap flanked with two archangels. From the south side, the Mother of God is approached by Serbian saints Symeon and Sava as mediators, and behind them, Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos and King Milutin, followed by St. Stefan. On the other side, Andronikos III Palaiologos is also approaching the Virgin. All inscriptions around the scene are in Greek and the Serbian king is referred to as a “founder of the church and the very beloved son-in-law of the mighty Emperor Andronikos Basileus and Autokrator Romaion.” Both rulers are wearing the same costume and Andronicos is standing on the suppedion decorated with two-headed eagles. Andronikos is wearing the Byzantine crown and black imperial sakkos and is holding in his hands a scepter and handing Milutin a bundle of three scrolls with gold seals. It is important to notice that Byzantine emperors appear in the Chilandar ktetor’s composition as rulers on whose territory the Serbian monastery was built and as guarantors of the founders legal rights [19] (p. 255).

Figure 8. King Milutin, fresco, 1321. Church of the Presentation of the Virgin, Monastery of Chilandar, southern part of the second zone of the east wall of the narthex. Courtesy Gallery of Frescoes, Belgrade.

8. Coins

The overall success of King Milutin’s endeavors, either militarily or culturally, was based on his financial power that came from the exploitation of rich silver mines in Brskovo, Trepča, Rudnik and Novo Brdo. Like his predecessors, he started minting his silver dinar, which weighed 2, 13 g and had a diameter of 21 mm (Figure 9), thus producing imitations of Venetian coins (grosso). At the beginning of his reign, King Milutin sustained a stable monetary policy. However large expenditures for military ventures forced him to increase his revenues, reducing the weight and quality of his coins [20] (p. 122). The coins gradually diminished in value, and toward the end of his epoch, they contained seven-eighths of silver compared to Venetian ones. This led to the ban of these coins by the Republic of Venice.

Figure 9. Milutin’s silver dinar, obverse and reverse of silver coin after 1282. Photo courtesy Marina Odak Mihailović.

On the obverse of the coin, King Milutin is represented with an open lily crown holding a scepter with fleur-de-lis at its top in the right hand and a double cross-bearing orb in his left hand. The ruler’s scepter is an inviolable sign of his power. On the reverse of Milutin’s silver dinar, Christ is represented sitting on the throne with the halo around his head. Although the sovereignty of Serbian rulers was predominantly derived from the sphere of Byzantine imperial ideology, according to Odak Mihailović [21] (p. 144), the iconography of Serbian coinage reflected the influences of the Western ideology of governance along with those of Byzantium. Influenced by Hungarian coinage, after 1276, King Dragutin’s coins already featured the image of the enthroned ruler in regal cape and dress, wearing a crown of the Western type and holding the orb and the fleur-de-lis scepter. Western insignia, such a crown, was present on the coins minted during the period of the kingdom, while the elements of Byzantine insignia were dominant on Serbian dinars during the imperial period.

9. Conclusions

The long and fruitful reign of King Milutin—that lasted almost 40 years—left many artistic testimonies. Politically but also artistically, King Milutin’s life can be divided into two very distinctive periods: before and after his marriage to the daughter of the ruling Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos in 1299. The first one is marked with the traditions of the “old” Raška school and the Nemanide ideology expressed through the iconography of endowments of his brother in Djurdjevi Stupovi and Arilje. The second one is characterized by the growing Byzantinization of Serbian society, evident in every aspect of life, including art. King Milutin’s building activity was huge and even exceeded the borders of his state. His endowments were erected in Thessaloniki (St. Nicolas Orphanos), Mt. Athos (Chilandar and the Hrusija tower), Constantinople (Petra Monastery with the catholicon of St. Jon the Baptist and a ξενων του Κραλη: a hospital, hostel and a studying facility) and The Holy Land (Monastery of St. Archangels in Jerusalem) [22] (pp. 61–63). More than fifteen of King’s Milutin portraits can be found in the monumental painting ensembles of Serbian medieval monasteries, as well as on two icons and the coins. This fact makes a unique case in Serbian Medieval art history that allows researchers to study different aspects of his representations.

Portraits of King Milutin painted in the territories of medieval Serbia and present-day North Macedonia after 1299 show the great self-awareness of the Serbian ruling society following military victories on Byzantine soil. This can be read first in the inscription’s language, with an emphasis on the full title and all-important royal insignia, and even in the choice of iconographic formulas, which indicated the heavenly origin of King Milutin’s power.

In Bogorodica Ljeviška, King Milutin is represented on the red background in full Byzantine costume with a Byzantine crown accompanied by the long inscription and without a church model—a clear political statement created to suggest his ultimate intention to replace the ruling Byzantine Emperor [16] (pp. 299–317). Except for the color of the sakkos, his costume did not change until the end of his life. However, the political messages of King Milutin’s iconography will be enriched with various meanings thanks to different figurative themes In Žiča, he leads a procession within the timeless Christmas Hymn; in Staro Nagoročino, he accepts a sword from the victorious St. George in King’s Church; in Studenica, via his ancestors, he attempts to compare himself to Christ; and in Gračanica, he accepts the heavenly sent crown.

However, the real crown of his political attempts emerges in visual form through the newly 14th century invented iconographical formula: the Nemanide Genealogical Tree, in which King Milutin openly emphasizes the parallelism between himself and the biblical king David. The only exception to King Milutin’s unlimited self-awareness is visible in the narthex of Chilandar, where, with his subordination to Andronikos II, he showed the acceptance of the Byzantine ideological views, i.e., his awareness of Serbian endowment being built in the Athos monastic community, i.e., on the territory of the Byzantine Empire.

Summarizing all these arguments, we can conclude that King Milutin already, during his lifetime, considered himself the most powerful ruler of the Nemanide dynasty. Using monumental art, he gradually made the very complex ideas of Byzantine political theology sensually recognizable—its origins and nature as a foundation of his rule. Thus, he paved the way for his grandson, Stefan IV Dušan, to elevate the status of the Serbian church to the level of Patriarchy two decades later, and to proclaim himself Emperor “like (…) the great Emperor Constantine, (…) ruler of many nations” [16] (p. 303).