Bast fiber crops are an important group of economic crops for the purpose of harvesting fibers from stems. These fibers are sclerenchyma fibers associated with the phloem of plants. They arise either with primary tissues from the apical meristem, or with secondary tissues produced by the lateral meristem. Fungal diseases have become an important factor limiting their yield and quality, causing devastating consequences for the production of bast fiber crops in many parts of the world.

- bast fiber crops

- molecular identification

- fungal disease

- DNA barcode

- PCR assay

1. Introduction

2. Bast Fiber Crops

Bast fiber crops are an important group of economic crops for the purpose of harvesting fibers from stems [20]. These fibers are sclerenchyma fibers associated with the phloem of plants. They arise either with primary tissues from the apical meristem, or with secondary tissues produced by the lateral meristem. Bast fiber is one of four major types of natural plant fibers, with the other three being leaf fiber (e.g., banana and pineapple fibers), fruit and seed fiber (e.g., cotton and coconut fiber), and stalk fiber (e.g., straw fiber from rice, wheat, and bamboo). Bast fiber crops comprise six main species (flax, hemp, ramie, kenaf, jute, and sunn hemp) that are broadly cultivated (Table 1) as well as a few others (kudzu, linden, milkweed, nettle, okra, and paper mulberry) with more limited fiber production [21]. Table 1 summarizes the main bast fiber crops, including their geographic distributions, habitats, commercial use, and main fungal diseases.|

Crop |

Main Distribution |

Main Characters of Growth Habitat |

Main Applications |

Main Fungal Diseases |

|---|

3. Fungal Pathogens of Bast Fiber Crops

|

Pathogen |

Disease |

Method |

Marker |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Target DNA |

Primer Name and Sequence (5′-3′) |

Size of PCR Product (bp) | Host Plant |

Geographic Region(s) |

Reference |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Reference | ||||||||||||||

|

Flax (Linum usitatissimum Linnaeus) |

France, Russia, Netherlands, Belarus, Belgium, Canada, Kazakhstan, China, India |

|||||||||||||

|

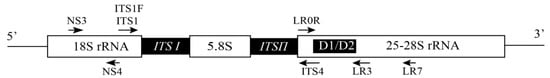

18S | Well-drained loam and cool, moist, temperate climates |

Linen, flax yarn, flax seed, linseed oil |

flax wilt, flax blight, flax anthracnose |

|||||||||||

|

Alternaria |

NS3 |

GCAAGTCTGGTGCCAGCAGCC |

Not mentioned |

[54 | ||||||||||

|

Hemp (Cannabis sativa Linnaeus) |

||||||||||||||

|

A. alternata |

China, Canada, USA, Europe, East Asia, Nepal |

Hemp leaf spot |

Grows at 16–27 °C, sufficient rain at the first six weeks of growth, short day length. |

Conventional PCR |

Textiles, hempseed oil, prescription drugs |

ITS |

hemp powdery mildew, hemp leaf spot disease, hemp blight, hemp root and crown rot wilt, hemp charcoal rot |

|||||||

Cannabis sativa | Shanxi, China |

Jute (Corchorus capsularis Linnaeus) |

India, Bangladesh, Burma, China |

Tropical lowland areas, humidity of 60% to 90%, rain-fed crop |

||||||||||

|

A. alternata |

Ramie black leaf spot |

Conventional PCR | Textiles, medicine |

ITS, GAPDH |

jute anthracnose, jute brown wilt, jute leaf spot |

|||||||||

Boehmeria nivea | Hunan, Hubei, China |

Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus Linnaeus) |

India, Bangladesh, China, Malaysia, Thailand |

Sandy loam and warm, humid subtropical, or tropical climates, few heavy rains or strong winds, at least 12 h light each day |

||||||||||

|

Cercospora | Textiles |

kenaf anthracnose, kenaf lack rot, kenaf sooty mold |

||||||||||||

] |

Ramie (Boehmeria nivea Linnaeus) Gaudich |

|||||||||||||

|

Cercospora cf. flagellaris |

China, Brazil, Philippines, India, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia |

Hemp leaf spot disease | Sandy soil and warm, wet climates, rainfall averaging at least 75 to 130 mm per month |

Not mentioned |

Textiles, soil and water conservation, medicine |

ITS, EF-1α, CAL, H3, actin |

ramie anthracnose, ramie powdery mildew, ramie black leaf spot, ramie blight |

|||||||

Cannabis sativa | Kentucky, USA |

Sunn Hemp (Crotalaria juncea Linnaeus) |

India, USA, China |

Wide variety of soil condition, altitude from 100 to 1000 m, temperatures above 28 °C, photoperiod-sensitive |

Cover crop or green manure, forage producer |

|||||||||

|

Colletotrichum |

sunn hemp fusarium wilt, sunn hemp root rot, sunn hemp powdery mildew |

|||||||||||||

|

C. corchorum capsularis |

Jute anthracnose |

ACT-512F |

Conventional PCR |

ACT, TUB2, CAL, GAPDH, GS, and ITS |

Corchorus capsularis L. |

Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangxi, and Henan, China |

||||||||

ATGTGCAAGGCCGGTTTCGC |

300 |

C. fructicola |

||||||||||||

|

ACT-783R |

Jute anthracnose |

Conventional PCR |

ACT, TUB2, CAL, GAPDH, GS, and ITS |

TACGAGTCCTTCTGGCCCATCorchorus capsularis L. |

Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangxi, and Henan, China |

|||||||||

|

C. fructicola |

Jute anthracnose | |||||||||||||

|

ß-tubulin |

Vd-btub-1F | Conventional PCR |

GCGACCTTAACCACCTCGTT |

ACT, TUB2, CAL, GAPDH, GS, and ITS |

Not mentioned |

Corchorus capsularis L. |

Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangxi, and Henan, China |

[26 |

||||||

] |

C. gloeosporioides |

|||||||||||||

|

Vd-btub-1R | Ramie anthracnose |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

CGCGGCTGGTCAGAGGA |

Boehmeria nivea |

HuBei, HuNan, JiangXi, and SiChuan, China |

||||||||

|

C. higginsianum |

Ramie anthracnose |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

|||||||||||

|

VertBt-F | Boehmeria nivea |

AACAACAGTCCGATGGATAATTC |

HuBei, China |

Not mentioned |

||||||||||

] | [ | ] |

C. phormii |

New Zealand flax anthracnose |

||||||||||

|

VertBt-R |

GTACCGGGCTCGAGATCG | Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Phormium tenax |

California, USA |

|||||||||

|

C. phormii |

New Zealand flax anthracnose |

Conventional PCR |

||||||||||||

|

VITubF2 |

GCAAAACCCTACCGGGTTATG | ITS |

Phormium tenax |

143 |

Perth, Australia |

|||||||||

|

C. siamense |

Jute anthracnose |

Conventional PCR |

ACT, TUB2, CAL, GAPDH, GS, and ITS |

Corchorus capsularis L. |

Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangxi, and Henan, China |

[27 | ||||||||

|

VITubRl | ] | [ | ] | |||||||||||

AGATATCCATCGGACTGTTCGTA |

Colletotrichum sp. |

Kenaf anthracnose |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Corchorus olitorius |

South Korea |

||||||||

|

VdTubF2 |

GGCCAGTGCGTAAGTTATTCT |

82 | [ | ][28 |

[] | |||||||||

] | [ | 39] |

Curvularia |

|||||||||||

|

VdTubR4 |

ATCTGGTTACCCTGTTCATCC |

C. cymbopogonis |

Hemp leaf spot |

|||||||||||

|

Bt2a | Conventional PCR |

25S |

GGTAACCAAATCGGTGCTGCTTTC |

Not mentioned |

Cannabis sativa |

] |

USA |

|||||||

|

Exserohilum |

||||||||||||||

|

Bt2b |

ACCCTCAGTGTAGTGACCCTTGGC |

E. rostratum |

Hemp floral blight |

Not mentioned |

ITS, RPB2 |

Cannabis sativa | ||||||||

|

CAL |

CL1 |

GARTWCAAGGAGGCCTTCTC |

Not mentioned |

[27][North Carolina, USA | ||||||||||

] |

Fusarium |

|||||||||||||

|

CL2 |

TTTTTGCATCATGAGTTGGAC |

F. oxysporum |

||||||||||||

|

CAL-228F |

Hemp roots and crown rot |

GAGTTCAAGGAGGCCTTCTCCC |

Conventional PCR |

ITS, EF-1α |

Not mentioned |

[45Cannabis sativa |

Canada |

|||||||

] | [ | ] |

F. oxysporum |

Jute brown wilt |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Corchorus olitorius |

Dhaka, Manikgonj, Kishorgonj, Rangpur, and Monirampur, Bangladesh | ||||||

|

CAL-737R |

CATCTTTCTGGCCATCATGG | [ | ][40] |

|||||||||||

|

F. oxysporum |

||||||||||||||

|

EF-1α |

Hemp wilt |

EF-1 |

Conventional PCR |

ATGGGTAAGGAGGACAAGAC |

ITS, EF-1α |

700 | Cannabis sativa |

California, USA |

||||||

] |

F. solani |

Hemp crown root |

Conventional PCR |

ITS, EF-1α |

Cannabis sativa |

Canada |

||||||||

|

EF-2 |

GGAGGTACCAGTGATCATGTT |

F. solani |

Hemp wilt |

Conventional PCR |

ITS, EF-1α |

|||||||||

|

EF1-728F |

CATCGAGAAGTTCGAGAAGG |

Not mentioned |

Cannabis sativa |

California, USA |

||||||||||

|

F. solani |

Sunn hemp root rot and wilt |

Conventional PCR |

||||||||||||

|

EF2 | ITS, EF-1α |

Crotalaria juncea |

Ceará, Brazil |

[ |

GGAGGTACCAGTGATCATGTT | |||||||||

|

F. brachygibbosum |

Hemp wilt |

Conventional PCR |

ITS, EF-1α |

|||||||||||

|

EF1-728F | Cannabis sativa |

California, USA |

CATCGAGAAGTTCGAGAAGG |

350 |

||||||||||

|

F. udum f. sp. crotalariae |

Sunn hemp fusarium wilt |

Conventional PCR |

EF-1α, β-tubulin |

Crotalaria juncea |

Tainan, China |

|||||||||

|

EF1-983R |

TACTTGAAGGAACCCTTACC |

Glomus |

||||||||||||

|

Endochitinase |

Vd-endoch-1F |

CTCGGAGGTGCCATGTACTG |

Not mentioned | |||||||||||

[ | ] | [38] |

G. mosseae |

Hemp root rot Conventional PCR |

25S |

Cannabis sativa |

USA | |||||||

|

Vd-endoch-1R |

ACTGCCTGGCCCAGGTTC | [ | ][52] |

|||||||||||

|

Golovinomyces |

||||||||||||||

|

GAPDH |

Vd-G3PD-2F |

CACGGCGTCTTCAAGGGT |

Not mentioned |

G. spadiceus |

Hemp powdery mildew |

Not mentioned |

ITS, 28S | |||||||

|

Vd-G3PD-1R |

CAGTGGACTCGACGACGTAC | Cannabis sativa |

Kentucky, USA |

|||||||||||

|

G. cichoracearum sensu lato |

Hemp powdery mildew |

Conventional PCR |

||||||||||||

|

GDF1 |

GCCGTCAACGACCCCTTCATTGA |

Not mentioned | ITS |

Cannabis sativa |

Atlantic Canada and British Columbia. |

|||||||||

|

G. cichoracearum |

Sunn hemp powdery mildew |

Not mentioned |

ITS |

Crotalaria juncea |

Florida, USA | |||||||||

|

GDR1 |

GGGTGGAGTCGTACTTGAGCATGT | [ | ][45] |

|||||||||||

|

Lasiodiplodia |

||||||||||||||

|

gpd-1 |

CAACGGCTTCGGTCGCATTG |

Not mentioned |

L. theobromae |

Kenaf black rot |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Corchorus olitorius |

Kangar Perlis, Malaysia |

||||||

|

gpd-2 |

GCCAAGCAGTTGGTTGTGC |

Leptoxyphium |

||||||||||||

|

GS |

GSF1 |

ATGGCCGAGTACATCTGG | ||||||||||||

Not mentioned |

L. kurandae |

Kenaf sooty mould |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Corchorus olitorius |

Iksan, Korea |

||||||||

[ | ||||||||||||||

|

GSR1 |

GAACCGTCGAAGTTCCAC |

Macrophomina |

||||||||||||

] |

Macrophomina phaseolina |

Hemp charcoal rot |

Conventional PCR |

EF-1α, CAL |

Cannabis sativa |

Southern Spain |

||||||||

|

Micropeltopsis |

||||||||||||||

|

Micropeltopsis cannabis |

Unknown |

Conventional PCR |

25S |

Cannabis sativa |

USA |

|||||||||

|

Orbilia |

||||||||||||||

|

Orbilia luteola |

Unknown |

Conventional PCR |

25S |

Cannabis sativa |

USA |

|||||||||

|

Pestalotiopsis |

||||||||||||||

|

Pestalotiopsissp. |

Hemp spot blight |

Conventional PCR |

25S |

Cannabis sativa |

USA |

|||||||||

|

Podosphaera |

||||||||||||||

|

P. xanthii |

Ramie powdery mildew |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Boehmeria nivea |

Naju, Korea |

|||||||||

|

Pythium |

||||||||||||||

|

P. dissotocum |

Browning and a reduction in root mass, stunting |

Conventional PCR |

ITS, EF-1α |

Cannabis sativa |

Canada |

|||||||||

|

P. myriotylum |

Browning and a reduction in root mass, stunting |

Conventional PCR |

ITS, EF-1α |

Cannabis sativa |

Canada |

|||||||||

|

P. myriotylum |

Hemp root rot and Wilt |

Conventional PCR |

ITS, COI, COII |

Cannabis sativa |

Connecticut, USA |

|||||||||

|

P. aphanidermatum |

Hemp root rot and crown wilt |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Cannabis sativa |

California, USA |

|||||||||

|

P. aphanidermatum |

Hemp crown and root Rot |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Cannabis sativa |

Indiana, USA |

|||||||||

|

P. ultimum |

Hemp crown and root Rot |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Cannabis sativa |

Indiana, USA |

|||||||||

|

Rhizoctonia | ||||||||||||||

|

ITS |

ITS1 |

TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG |

334-738 |

|||||||||||

|

ITS4 |

TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC |

|||||||||||||

|

Binucleate R. spp. |

Hemp wilt |

Conventional PCR |

25S |

Cannabis sativa |

USA |

|||||||||

|

Sclerotinia |

||||||||||||||

|

Sclerotinia minor |

Hemp crown rot |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Cannabis sativa |

San Benito County, Canada |

|||||||||

|

Sphaerotheca |

||||||||||||||

|

S. macularis |

Hemp powdery mildew |

Conventional PCR |

25S |

V. dahliae |

flax wilt |

qPCR |

ITS |

Linum usitatissimum |

Normandy, France |

|||||

|

V. dahliae |

flax wilt |

qPCR |

ß-tubulin |

Linum usitatissimum |

Germany |

|||||||||

|

V. tricorpus |

flax wilt |

qPCR |

ITS |

Linum usitatissimum | ||||||||||

|

NS4 |

CTTCCGTCAATTCCTTTAAG |

|||||||||||||

|

28S |

LR0R |

GCAAGTCTGGTGCCAGCAGCC |

Not mentioned |

|||||||||||

|

LR3 |

GCAAGTCTGGTGCCAGCAGCC |

|||||||||||||

|

25S |

LROR |

ACCCGCTGAACTTAAGC |

1431 |

|||||||||||

|

LR7 |

TACTACCACCAAGATCT |

|||||||||||||

|

ACT |

||||||||||||||

|

Vd-ITS1-45-F |

CCGGTCCATCAGTCTCTCTG |

334 |

||||||||||||

|

Vd-ITS2-379-R |

ACTCCGATGCGAGCTGTAAC |

|||||||||||||

|

ITS1-F |

CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA |

700 |

||||||||||||

|

ITS4 |

TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC |

|||||||||||||

|

VtF4 |

CCGGTGTTGGGGATCTACT |

123 |

||||||||||||

|

VtR2 |

GTAGGGGGTTTAGAGGCTG |

|||||||||||||

|

ITS 4 |

TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC |

Not mentioned |

||||||||||||

|

ITS 5 |

GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG |

|||||||||||||

|

RPB2 |

bRPB2-6F |

TGGGGYATGGTNTGYCCYGC |

Cannabis sativa |

USA |

||||||||||

|

Verticillium |

||||||||||||||

|

V. dahliae |

flax wilt |

Conventional PCR |

ITS |

Linum usitatissimum |

La Haye Aubrée, France |

Germany |

||||||||

|

V. longisporum |

flax wilt |

qPCR |

ß-tubuIin |

Linum usitatissimum |

Germany |

|||||||||

qPCR: quantitative PCR, ITS: internal transcribed spacer, GAPDH: glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, GS: glutamate synthetase, EF-1α: translation elongation factor 1-α, CAL: calmodulin, H3: histone subunit 3, ACT: actin, TUB2: ß-tubulin, RPB2: RNA polymerase subunit B2, COI: cytochrome oxidase subunit I, COII: cytochrome oxidase subunit II.

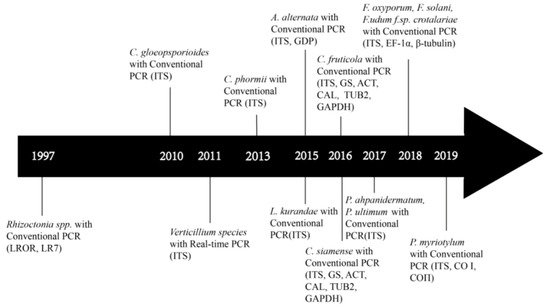

4. Development of Molecular Identification of Bast Fiber Fungal Pathogens

Not mentioned |

[ |

] |

[ |

] |

bRPB2-7R |

GAYTGRTTRTGRTCRGGGAAVGG |

5. Target DNA Selection and Molecular Assays of Fungal Pathogens on Bast Fiber Crops