After the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant (FNPP)PP accident in March 2011 much attention was focused to the biological consequences of ionizing radiation and radionuclides released in the area surrounding the nuclear plant. This unexpected mishap led to the emission of radionuclides in aerosol and gaseous forms from the power plant, which contaminated a large area, including wild forest, cities, farmlands, mountains, and the sea, causing serious problems. Large quantities of 131I, 137Cs, and 134Cs were detected in the fallout. People were evacuated but the flora continued to be affected by the radiation exposure and by the radioactive dusts’ fallout.

- ionizing radiation

- Fukushima Dai-ichi

- Plant

- flora

1. Background

Following the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant (FNPP) accident in March 2011, due to the Great Eastern Japan earthquake and tsunami, massive amounts of radioactive materials were released into the environment. Due to the direction of the wind, the great majority of these materials poured into the Pacific Ocean; however, some of them spilled over to coastal areas, causing soil contamination by radionuclides, mainly in Fukushima prefecture [1]. Among the radionuclides most deposited in the soil, 137Cs is the most dangerous as it has a relatively long half-life compared to other radioactive substances released by FNPP [2], this is way the authors have focused the attention on this radionuclide for this work. In addition, 137Cs contaminated soil binds strongly to clay and the migration rate of clay-bound 137Cs exhibits low mobility, less than 1 cm per year, suggesting that most of 137Cs is superficially distributed in the soil. 137Cs can emit γ-rays; hence, unusually high air dose rates continue over land areas [3]. In addition, although the number of radionuclides released in the coastal area decreased, they continued to diffuse from the FNPP through the aquifers. Consequently, all the flora and fauna present at the time of the accident received and continue to receive high doses of radiation from Fukushima. Therefore, the finding of adverse effects in wild organisms in the Fukushima area resulting from long-term, low-dose radiation exposure is of great concern [4]. Over the years, several investigations have tried to determine the levels of contamination with radioactive materials or to estimate the doses of radiation exposure in terrestrial organisms living around Fukushima. However, there are few studies on the impacts of environmental radiation on wild organisms. Furthermore, flora and wildlife are strongly influenced by human activities [4][5]. Following the incident, the Japanese government designated “Areas where residents are not allowed to live” and “Areas where residents are expected to have difficulty returning for a long time” near the FNPP which have higher annual radiation doses to 20 mSv. The result was a mass evacuation from these areas in the long term. While radiation levels in most of the evacuation zone are not considered extremely lethal to wildlife, land use change due to decontamination activities and the cessation of agricultural activities are believed to significantly affect flora, fauna, and ecosystems in these areas [6][7][8][9].

2. The Effects of Ionizing Radiation on Plants

3. Current and Future Perspectives: Management in the Medical Field

References

- Tanaka, S. Accident at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power stations of TEPCO—outline & lessons learned. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2012, 88, 471–484.

- Kenyon, J.A.; Buesseler, K.O.; Casacuberta, N.; Castrillejo, M.; Otosaka, S.; Masqué, P.; Drysdale, J.A.; Pike, S.M.; Sanial, V. Distribution and Evolution of Fukushima Dai-ichi derived 137Cs, 90Sr, and 129I in Surface Seawater off the Coast of Japan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 15066–15075.

- Takahashi, J.; Tamura, K.; Suda, T.; Matsumura, R.; Onda, Y. Vertical distribution and temporal changes of 137Cs in soil profiles under various land uses after the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 2015, 139, 351–361.

- I Batlle, J.V.; Aono, T.; Brown, J.E.; Hosseini, A.; Garnier-Laplace, J.; Sazykina, T.; Steenhuisen, F.; Strand, P. The impact of the Fukushima nuclear accident on marine biota: Retrospective assessment of the first year and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 487, 143–153.

- Barquinero, J.F.; Fattibene, P.; Chumak, V.; Ohba, T.; Della Monaca, S.; Nuccetelli, C.; Akahane, K.; Kurihara, O.; Kamiya, K.; Kumagai, A.; et al. Lessons from past radiation accidents: Critical review of methods addressed to individual dose assessment of potentially exposed people and integration with medical assessment. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106175.

- Nagataki, S.; Takamura, N.; Kamiya, K.; Akashi, M. Measurements of individual radiation doses in residents living around the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant. Radiat. Res. 2013, 180, 439–447.

- Orita, M.; Hayashida, N.; Nakayama, Y.; Shinkawa, T.; Urata, H.; Fukushima, Y.; Endo, Y.; Yamashita, S.; Takamura, N. Bipolarization of risk perception about the health effects of radiation in residents after the accident at Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129227.

- Tamaoki, M. Studies on radiation effects from the Fukushima nuclear accident on wild organisms and ecosystems. Glob. Environ. Res. 2016, 20, 73–82.

- Hidaka, T.; Kasuga, H.; Kakamu, T.; Fukushima, T. Discovery and Revitalization of “Feeling of Hometown” from a Disaster Site Inhabitant’s Continuous Engagement in Reconstruction Work: Ethnographic Interviews with a Radiation Decontamination Worker over 5 Years Following the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Accident 1. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2021, 63, 393–405.

- Ludovici, G.M.; Cascone, M.G.; Huber, T.; Chierici, A.; Gaudio, P.; de Souza, S.O.; d’Errico, F.; Malizia, A. Cytogenetic bio-dosimetry techniques in the detection of dicentric chromosomes induced by ionizing radiation: A review. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 482.

- Esnault, M.A.; Legue, F.; Chenal, C. Ionizing radiation: Advances in plant response. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2010, 68, 231–237.

- Ludovici, G.M.; de Souza, S.O.; Chierici, A.; Cascone, M.G.; d’Errico, F.; Malizia, A. Adaptation to ionizing radiation of higher plants: From environmental radioactivity to chernobyl disaster. J. Environ. Radioact. 2020, 222, 106375.

- Dighton, J.; Tugay, T.; Zhdanova, N. Fungi and ionizing radiation from radionuclides. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 281, 109–120.

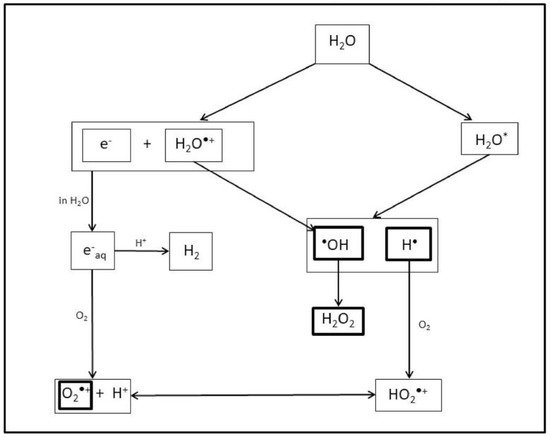

- Azzam, E.I.; Jay-Gerin, J.P.; Pain, D. Ionizing radiation-induced metabolic oxidative stress and prolonged cell injury. Cancer Lett. 2012, 327, 48–60.

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 217037.

- Nita, M.; Grzybowski, A. The Role of the Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress in the Pathomechanism of the Age-Related Ocular Diseases and Other Pathologies of the Anterior and Posterior Eye Segments in Adults. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 3164734.

- Reisz, J.A.; Bansal, N.; Qian, J.; Zhao, W.; Furdui, C.M. Effects of ionizing radiation on biological molecules--mechanisms of damage and emerging methods of detection. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 21, 260–292.

- Smith, T.A.; Kirkpatrick, D.R.; Smith, S.; Smith, T.K.; Pearson, T.; Kailasam, A.; Herrmann, K.Z.; Schubert, J.; Agrawal, D.K. Radioprotective agents to prevent cellular damage due to ionizing radiation. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 232.

- Manova, V.; Gruszka, D. DNA damage and repair in plants—From models to crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 885.

- Huang, R.; Zhou, P.K. DNA damage repair: Historical perspectives, mechanistic pathways and clinical translation for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 254.

- Watson, J.M.; Platzer, A.; Kazda, A.; Akimcheva, S.; Valuchova, S.; Nizhynska, V.; Nordborg, M.; Riha, K. Germline replications and somatic mutation accumulation are independent of vegetative life span in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12226–12231.

- Caplin, N.; Willey, N. Ionizing Radiation, Higher Plants, and Radioprotection: From Acute High Doses to Chronic Low Doses. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 847.

- Morishita, T.; Shimizu, A.; Yamaguchi, H.; Degi, K. Development of common buckwheat cultivars with high antioxidative activity -’Gamma no irodori’, ‘Cobalt no chikara’ and ‘Ruchiking’. Breed. Sci. 2019, 69, 514–520.

- Maity, J.P.; Kar, S.; Banerjee, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Santra, S.C. Effects of gamma irradiation on long-storage seeds of Oryza sativa (cv. 2233) and their surface infecting fungal diversity. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2009, 78, 1006–1010.

- Le Caër, S. Water radiolysis: Influence of oxide surfaces on H2 production under ionizing radiation. Water 2011, 3, 235–253.

- Borg, M.; Brownfield, L.; Twell, D. Male gametophyte development: A molecular perspective. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1465–1478.

- Ma, H.; Sundaresan, V. Development of flowering plant gametophytes. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2010, 91, 379–412.

- Malizia, A.; Chierici, A.; Biancotto, S.; D’Arienzo, M.; Ludovici, G.M.; d’Errico, F.; Manenti, G.; Marturano, F. The HotSpot Code as a Tool to Improve Risk Analysis During Emergencies: Predicting I-131 and CS-137 Dispersion in the Fukushima Nuclear Accident. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2021, 11, 473–486.

- Beresford, N.A.; Horemans, N.; Copplestone, D.; Raines, K.E.; Orizaola, G.; Wood, M.D.; Laanen, P.; Whitehead, H.C.; Burrows, J.E.; Tinsley, M.C.; et al. Towards solving a scientific controversy–The effects of ionising radiation on the environment. J. Environ. Radioact. 2020, 211, 106033.

- Chierici, A.; Malizia, A.; di Giovanni, D.; Fumian, F.; Martellucci, L.; Gaudio, P.; d’Errico, F. A low-cost radiation detection system to monitor radioactive environments by unmanned vehicles. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 314.

- Marturano, F.; Martellucci, L.; Chierici, A.; Malizia, A.; Di Giovanni, D.; d’Errico, F.; Gaudio, P.; Ciparisse, J.F. Numerical fluid dynamics simulation for drones’ chemical detection. Drones 2021, 5, 69.

- Martellucci, L.; Chierici, A.; Di Giovanni, D.; Fumian, F.; Malizia, A.; Gaudio, P. Drones and Sensors Ecosystem to Maximise the “Storm Effects” in Case of CBRNe Dispersion in Large Geographic Areas. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2021, 11, 377–386.

- Fumian, F.; Chierici, A.; Bianchelli, M.; Martellucci, L.; Rossi, R.; Malizia, A.; Gaudio, P.; d’Errico, F.; Di Giovanni, D. Development and performance testing of a miniaturized multi-sensor system combining MOX and PID for potential UAV application in TIC, VOC and CWA dispersion scenarios. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 913.

- Di Giovanni, D.; Fumian, F.; Chierici, A.; Bianchelli, M.; Martellucci, L.; Carminati, G.; Malizia, A.; d’Errico, F.; Gaudio, P. Design of Miniaturized Sensors for a Mission-Oriented UAV Application: A New Pathway for Early Warning. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2021, 11, 435–444.

- Kumagai, A.; Tanigawa, K. Current status of the Fukushima health management survey. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2018, 182, 31–39.

- Ishikawa, T.; Yasumura, S.; Ozasa, K.; Kobashi, G.; Yasuda, H.; Miyazaki, M.; Akahane, K.; Yonai, S.; Ohtsuru, A.; Sakai, A.; et al. The Fukushima Health Management Survey: Estimation of external doses to residents in Fukushima Prefecture. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12712.

- Liutsko, L.; Oughton, D.; Sarukhan, A.; Cardis, E.; SHAMISEN Consortium. The SHAMISEN Recommendations on preparedness and health surveillance of populations affected by a radiation accident. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106278.

- Ohba, T.; Liutsko, L.; Schneider, T.; Barquinero, J.F.; Crouaïl, P.; Fattibene, P.; Kesminiene, A.; Laurier, D.; Sarukhan, A.; Skuterud, L.; et al. The SHAMISEN Project: Challenging historical recommendations for preparedness, response and surveillance of health and well-being in case of nuclear accidents: Lessons learnt from Chernobyl and Fukushima. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106200.

- Sutton, R.T.; Pincock, D.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sadowski, D.C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kroeker, K.I. An overview of clinical decision support systems: Benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 17.