The advancement of natural-based biomaterials in providing a carrier has revealed a wide range of benefits in the biomedical sciences, particularly in wound healing, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Incorporating nanoparticles within polymer composites has been reported to enhance scaffolding performance, cellular interactions and their physico-chemical and biological properties in comparison to analogue composites without nanoparticles. Combining therapies consisting of nanoparticles and biomaterials could be promising for future therapies and better outcomes in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

1. Introduction

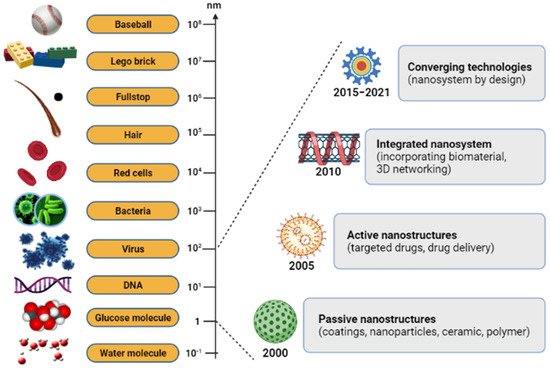

Nanoparticle-based therapies have a wide range of applications nowadays, and advances in nanotechnology offer novel solutions to disease problems. Recently, nanodelivery systems are rapidly developing new materials in the nanoscale range that are employed to deliver therapeutic agents to specific targeted sites in a controlled manner. It has offered numerous exciting possibilities in healthcare, and a few products are now available on the market. Nanotechnology is essential technology in the 21st century, with an atomic group at the nano-scale size of 1–100 nm

[1][2][1,2].

ItWe can

be obtain

ed it from natural sources, chemically synthesize it, or obtain it as one of the by-products of forming nanoparticles

[3][4][3,4]. The nano-scale science and engineering fields are consolidated under a unified science-based definition and a twenty-year research and development vision for nanotechnology (

Figure 1)

[5]. There has been a steadily growing interest in using nanoparticles over the last few years. In modern-day medicine, nanoparticles have become an indispensable tool for bioactive agent delivery and can be used in disease monitoring therapy

[6]. Generally, nanoparticles were studied because of their size-dependent physical and chemical properties. Besides displaying nanoparticles, there are other examples of the products in nano-scale technology, such as nanofibers and nanopatterned surfaces, which have also been used to direct cell behavior in various biomedical applications

[7]. The advantages of nanoparticle characteristics and composition, including a high surface area with adjustable surface properties and high penetration ability, make it one of the widely preferred candidates

[8]. Notwithstanding the other possible benefits, a significant advantage of nanoparticles is their beneficial size and shape, with the ability to improve their appearance. An assortment of nanoparticle-organized materials can be developed and applied today, and can benefit researchers’ ability to observe at a cellular level without causing significant interference. Based on the success of nanoparticles in passing through cell membranes, biomaterials with natural properties functioning with other suitable features can be constructed and applied

[9].

Figure 1. The relative size scale of macro-, micro-, and nanoscopic objects with the timeline for the nanotechnology development.

Biomaterials are classified into two categories, the first of which includes synthetic polymers including polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)

[10], polyethylene glycol (PEG)

[11], and polylactide (PLA)

[12]. Meanwhile, the second category is from natural-based polymers such as cellulose

[13], collagen

[14][15][14,15], gelatin

[16], chitosan

[17], and silk fibroin

[18] which are mainly from animals and plants. Natural-based biomaterials are easily accessible, usually non-toxic and non-immunogenic, besides displaying excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability properties, which have been pinpointed

[19]. However, natural-based biomaterials have certain drawbacks due to their weak mechanical strength, without a suitable crosslinker as a supporting component to enhance the stability and assembly of complex structures from the fabricated biomaterials

[20]. Moreover, natural-based biomaterials, particularly collagen has been abundantly found in the extracellular matrix (ECM) of human tissue

[21]. Consequently, they are intrinsically able to point to cell identification sites that allow them to interact with the surrounding cells and ECM. Because they are chemically compatible and have functional groups, they can incorporate with nanoparticles or conjugate with other target molecules. These chemical modifications will affect their solubility, permeability, charge, circulation time, loading efficiency, and interaction with target receptors

[22]. An overall safety assessment, however, is necessary before their clinical application. The use of natural-based biomaterials incorporated with nanoparticles is also an attractive approach that is most desirable for regenerative tools.

Strategies for applying the biomaterials to cure or treat diseases can be achieved in one of two approaches: either with the features of the nano-scaled materials used, or with the materials as a carrier molecule, to deliver active compounds pharmaceutically to the specific site

[23]. Up until now, researchers have focused on nanoparticle-based biocompatible materials, which are increasingly prevalent and used in a variety of potential biomedical engineering applications, including drug delivery systems

[24], wound healing

[25][26][25,26], tissue engineering

[20][27][20,27], dentistry

[28][29][28,29], cancer therapy

[30] and other related research areas. Despite their interesting applications, research into the use of nanoparticles as biomaterials is also broad

[31][32][33][31,32,33]. The nanoparticle-incorporated biomaterials provide a perfect composite material, demonstrating new or improved properties and activated therapeutics. The structural properties of these composite biomaterials, and the arrangement of each constituent of nanoparticles, synergistically enhance biomedical capabilities. By discovering nanoparticle-incorporated natural-based biomaterials, this has great implications for approaches involving biological subjects. The ability to modify the properties of biomaterials methodically by monitoring their structures allows them to be used for the treatment, diagnosis and biological system of regenerative dysfunction

[34].

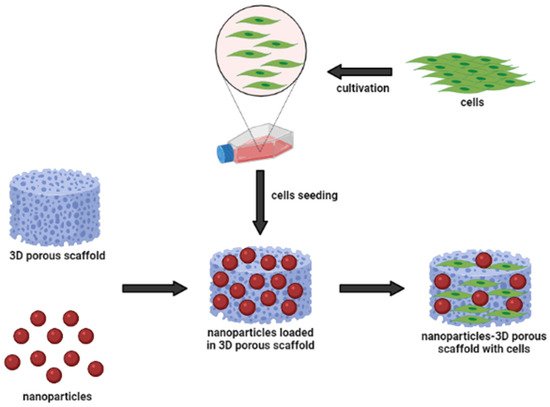

Figure 2 shows a schematic representation of the nanoparticle-incorporated natural-based biomaterial scaffolds for delivering bioactive molecules. In addition, the incorporation of functionalized nanoparticles into a porous sponge, together with cells, has developed a tissue-engineered scaffold for biomedical applications. These nanoparticles can act as nanocarriers to slowly release the cargo (bioactive molecules) to the target site for long-term efficacy. They may influence changes in cell morphology and function, based on the types of biomaterials. Occasionally, nanoparticles can cause inflammatory responses between cell interactions; however, they are easily incorporated into implant design to modulate the inflammatory responses. To develop multi-functional platforms, the incorporation of nanoparticles into biomaterial scaffolds such as hydrogels and electrospun fibers is primarily governed by pore size, which mostly enhance the resulting efficacy of the scaffolds. Hence,

we can say that incorporating different types of nanoparticles with advancing biomaterials is of great interest. Investigators and researchers further scrutinize the interactions of nanoparticle-incorporated natural-based biomaterials to detect their cellular response

[35][36][35,36]. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to understand the underlying mechanisms, including cellular functions and signaling pathways, in mediating wound healing.

Figure 2.

Nanoparticles and biomaterial-based porous scaffold for the delivery of bioactive molecules.

2. Biological Cellular Effects and Signaling Pathways

There has been increasing evidence that the biological properties of the scaffold affect various types of cellular behavior, including cell compatibility, viability, proliferation, and migration [37][104]. To address another important pathway of nanoparticle-incorporated biomaterials towards skin penetration, Kumar et al. [38][105] discussed the outcomes of using natural compound particles with incorporated biomaterials in skin tissue engineering applications. Based on available knowledge from the findings, the researchers used nanoparticles as carriers, due to their biological, electrical, mechanical and antibacterial properties [36]. As nanoparticles are implanted in the scaffold, it was found to develop the cytocompatibility of the particle substitute material and provide an appropriate surface morphology to enhance cellular functions. The biocompatibility and porous structure of scaffolds allow the cells to adhere to the surface of the scaffold effectively. Biological assays, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and MTT 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays, showed the proper cell attachment and proliferation of the prepared scaffolds. Both MTT and LDH assays are indirect tests known as the primary method for determining the toxicity of compounds with the scaffold, and number of damaged cells released into the culture media, respectively [26].

Due to special distributions of incorporated nanoparticles within the scaffolds in skin tissues, scientists also studied the effect of nanoparticles on cell proliferation and migration to skin cells. In the application of wound healing, recent studies based on the in vitro scratch experiments and in vivo animal studies have demonstrated positive results. The incorporation of nanoparticles into natural-based polymeric biomaterials significantly promoted cell proliferation and migration, which are the biological functions crucial for wound site closure, as well as restoration of barrier function [39][40][41][106,107,108]. The authors shared their findings, indicating that the cell migration path in the scratch area was shortened, and the migration rate increased after using their scaffoldings, which demonstrated excellent performance. These have shown that nanoparticles can act as a biological molecule; meanwhile natural-based biomaterials can be used as a substrate for cell growth, stimulating proliferation and migration. Accordingly, nanoparticles themselves promoted the proliferation and migration of human epidermal cells and human fibroblasts in vitro. Their proliferative-promoting effect always depends on their concentration and duration of action [42][109]. In addition, the combined application of nanoparticles and biomaterials had a synergistic promoting effect on human epidermal cell proliferation and wound healing. This is possible due to the scaffolds, which can absorb wound exudate and maintain a moist environment, necessary for cellular proliferation at the wound site. After these discoveries, the hydrophilic nature of the natural-based biomaterials’ polymer matrix characteristics was shown to be close to the value of fibroblast proliferation and migration [43][110].

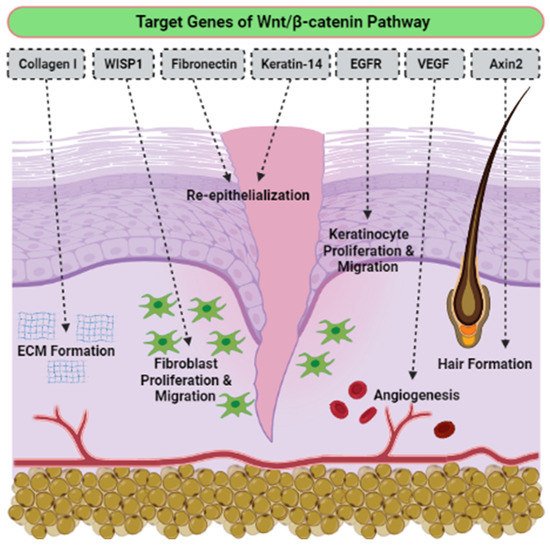

TEven though there is no determination of signaling pathways in the selected articles, we have accumulated evidence of the activation signaling pathways that are critically involved in proliferation, migration cells, and wound healing. The o the best of our knowledge, the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays a vital role in the proliferative phase of wound healing and tissue regeneration after injury. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is activated in the dermis of the wound bed immediately after skin injury. β-catenin is a subunit of the cadherin protein complex, where Wnt plays a specific role in the regulation of β-catenin function [44][45][46][111,112,113]. The signaling of Wnt is mediated by multi-protein complexes together, which consist of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3β), Axin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and casein kinase 1 (CK1) in the cytoplasm. Several target genes have been identified in cutaneous wound healing, as listed in Table 14. The Wnt/β-catenin activation pathway transcriptionally induces target genes such as Collagen I, Axin2, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Fibronectin, Keratin-14, VEGF and WISP1 during the wound repair process (Figure 36). Essentially, different Wnt/β-catenin signaling target genes contribute to the various events that occur during wound healing. For example, EGFR regulates the proliferation and migration of keratinocytes; meanwhile, collagen-1 plays a role in ECM formation. The up-regulation or rearrangement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling enhances the proliferation and migration of dermal fibroblasts, thus making them into distinct myofibroblasts. Therefore, it helps to reduce the surface area of the growing scar. Furthermore, the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway not only significantly facilitates migration and differentiation of keratinocytes in the epidermal layer, but it also induces angiogenesis and epithelial remodeling, which directly enhances skin wound healing [47][48][114,115].

Figure 36.

The effects of Wnt/β-catenin activated pathway, targeting genes in wound healing.

Table 14.

Target genes involved in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is related to wound healing.

| Wnt Target Genes |

Role in Wound Healing |

| Axin2 |

Hair formation through activation of hair follicles |

| Collagen I |

Key protein of ECM synthesized during the proliferative phase |

| Collagen III |

Key protein of ECM synthesized during the early proliferative phase |

| EGFR |

Regulation of keratinocyte migration to wound bed |

| Endothelin-1 |

Regulation of fibrosis and calcification |

| Fibronectin |

ECM formation and re-epithelialization |

| Keratin-14 |

Re-epithelialization |

| VEGF |

Stimulation of angiogenesis |

| WISP1 |

Promotion of dermal fibroblast proliferation and migration |

On the other hand, the TGF-β pathway is also involved in skin wound healing and dermal fibrosis. It is elaborated differently in the regulation of healing rate, which depends on the isoforms [49][116]. For example, TGF-β1 acts as a fibrosis stimulant factor; meanwhile, TGF-β3 regulates anti-scar activity. In adulthood and embryonic development, the Notch pathway controls epidermal cell differentiation [50][117], maintains skin homeostasis, and promotes angiogenesis [51][52][53][118,119,120]. A previous study reported that the activation of the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathway is required, and sufficient for hair follicle neogenesis (HFN) [54][121]. Nevertheless, the need for Shh regulation may differ in the development of embryonic hair follicles (HF) and adult HFN. If epithelial Wnts are sufficient for embryonic HF development, both epithelial and dermal Wnts are still required for adult HFN [55][56][122,123]. Thus, targeting activated signaling pathways could provide an effective therapeutic approach for regenerative skin wound healing.

3. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

All of the above-reported results strongly indicate that natural-based products that incorporate nanoparticles are effective and safe for use in treatment. However, there are still some health hazard concerns, especially regarding toxicity due to uncontrollable use and release. With this in mind, the incorporation of nanoparticles with natural-based biomaterials should be considered, to make the use of nanoparticles’ slow-release, easier, safer and more environmentally friendly. This study also identifies mechanism through which nanoparticle-incorporated biomaterials affect cellular and molecular signaling pathways. Studies suggest that Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways play important roles in tissue regeneration, specifically in cutaneous repair. The interaction between the two pathways might play a vital role in the regulation of healing. By understanding the mechanism involved in the signaling pathways for wound healing,

itwe can identify new targets for the development of regenerative wound healing using nanoparticles incorporated into natural-derived biomaterials, combined with the therapeutic agents.

To date, bioscaffold-based strategies developed for therapeutic applications present many challenges, and also new opportunities. Recent advancements in natural-based biomaterial synthesis have enabled researchers and scientists to incorporate many nanoparticles, thus facilitating better tissue regeneration with fewer toxicity effects. Despite these recent improvements, more efforts should be made to advance the fabrication of bioscaffolds through a combination of nanoparticles and biomaterials. Tailor-made therapies will become increasingly relevant in coming days. In the future, more clinical trials and in vivo studies will help us to realize the widespread commercial use of natural-based scaffolds incorporating nanoparticles with cost-effectiveness and ease of use.