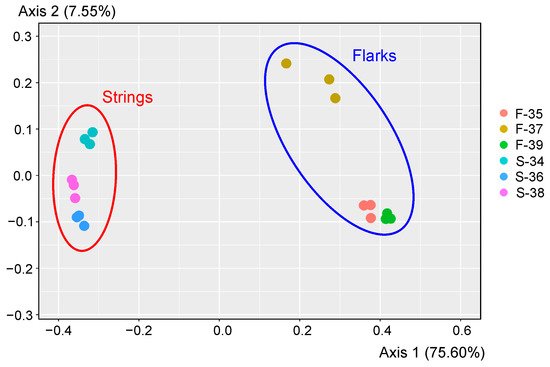

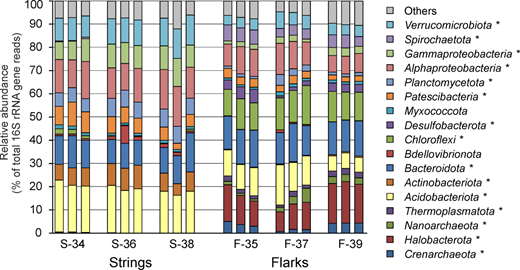

Large areas in the northern hemisphere are covered by extensive wetlands, which represent a complex mosaic of raised bogs, eutrophic fens, and aapa mires all in proximity to each other. Aapa mires differ from other types of wetlands by their concave surface, heavily watered by the central part, as well as by the presence of large-patterned string-flark complexes. The microbial communities in raised strings were clearly distinct from those in submerged flarks. Strings were dominated by the Alpha- and Gammaproteobacteria. Other abundant groups were the Acidobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Verrucomicrobiota, Actinobacteriota, and Planctomycetota. Archaea accounted for only 0.4% of 16S rRNA gene sequences retrieved from strings. By contrast, they comprised about 22% of all sequences in submerged flarks and mostly belonged to methanogenic lineages. Methanotrophs were nearly absent. Other flark-specific microorganisms included the phyla Chloroflexi, Spirochaetota, Desulfobacterota, Beijerinckiaceae- and Rhodomicrobiaceae-affiliated Alphaproteobacteria, and uncultivated groups env.OPS_17 and vadinHA17 of the Bacteroidota. Such pattern probably reflects local anaerobic conditions in the submerged peat layers in flarks.

- aapa mire

- microbial diversity

- methanogens

- Acidobacteriota

1. Introduction

2. Study Site

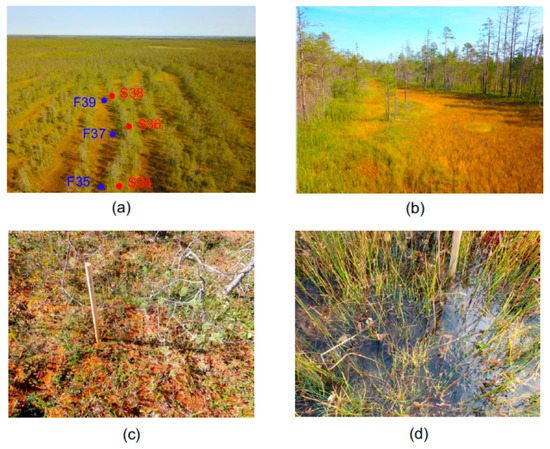

The object of this study was Piyavochnoe mire located in the north-west of Vologda region of North European Russia in the southern part of the middle taiga subzone. This is a large (80 km2) mire system composed of several raised bogs, aapa-mires and fen massifs, and a number of intramire primary lakes [31]. In the Piyavochnoe mire, the mire massif of the aapa type (coordinates 60.475 N, 36.504 E) is located in a separate depression and has a pronounced string-flark microrelief (alternation of forested Sphagnum ridges, grassed depression and low Sphagnum carpets located between them) in the central part (Figure 1). This aapa mire belongs to the Onega–Pechora aapa group, but has some features characteristic of the Karelian ring aapa mires [31].

3. Main Characteristics of Peat in Strings and Flarks

| Sample ID | S-34 | S-36 | S-38 | F-35 | F-37 | F-39 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | string | string | string | flark | Stringflark | S-34 | 1937flark | |||||

| 0.803 | 249.7 | 6.08 | Water level (cm) * | −17…−19 | −10…−12 | −11…−13 | +9…+10 | +8…+10 | +7…+9 | |||

| S-36 | 1352 | 0.805 | 199.8 | 5.81 | pH ** | 4.62 | 5.19 | 5.04 | 5.5 | 5.94 | 5.74 | |

| T, °C | ||||||||||||

| S-38 | 1657 | 0.797 | 218.0 | 5.90 | 18.9 | 17.4 | 16.5 | 13.4 | 17.7 | 15.1 | ||

| Flark | F-35 | 1230 | 0.706 | 80.8 | 5.03 | Peat characteristics | ||||||

| F-37 | 1705 | |||||||||||

| 0.759 | 152.4 | 5.65 | Total organic carbon (%) | 97.2 | 98.1 | 97.3 | ||||||

| F-39 | 1816 | 97.2 | 97.2 | 97.4 | ||||||||

| 0.729 | 107.5 | 5.47 | N-NH4 (mg kg −1) | 171.9 | 141.1 | 155.9 | 182.5 | 329.1 | 237.8 | |||

| N-NO3 (mg kg −1) | 19.7 | 10.1 | 20.6 | 8.4 | 11.3 | 9.9 | ||||||

| SO4 (mg L −1) ** | 259 | 185 | 317 | 52 | 61 | 37,5 | ||||||

| Fe (mg kg −1) | 380 | 450 | 460 | 500 | 750 | 830 | ||||||

| Ca (mg kg −1) | 8100 | 6500 | 8000 | 3700 | 6000 | 7200 | ||||||

| Mg (mg kg −1) ** | 740 | 980 | 1040 | 430 | 570 | 670 | ||||||

| P (mg kg −1) ** | 1210 | 1340 | 1190 | 1070 | 1130 | 1110 | ||||||

| Plant community (dominant species) |

Pinus sylvestris–Empetrum hermaphroditum–Sphagnum fuscum | Carex lasiocarpa–Scorpidium scorpioides | ||||||||||

| Vegetation coverage | 97–99% | 50–60% | ||||||||||

34. Diversity of Microbial Communities

| Peat Type | Sample ID | Richness | Peilous Evenness | Jost | Shannon |

|---|

45. Microbial Community Composition at the Phylum Level

Figure 3. Prokaryotic community composition in string and flark peat samples, according to results of 16S rRNA gene profiling. Community composition is shown at the phylum level, with exception of Proteobacteria, for which classes Alpha- and Gammaproteobacteria are shown. All replicate samples (three per sampling site) are presented. Lineages with statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in relative abundance in strings and flarks are marked with an asterisk.

References

- Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. Global Wetland Outlook: State of the World’s Wetlands and Their Services to People; Ramsar Convention Secretariat: Gland, Switzerland, 2018.

- Finlayson, C.M.; D’Cruz, R.; Davidson, N.C. Wetlands and water: Ecosystem services and human well-being. In Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 17–66.

- Gorham, E. Northern peatlands: Role in the carbon cycle and probable responses to climatic warming. Ecol. Appl. 1991, 1, 182–195.

- Matthews, E.; Fung, I. Methane emission from natural wetlands: Global distribution, area, and environmental characteristics of sources. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1987, 1, 61–86.

- Aselmann, I.; Crutzen, P.J. Global distribution of natural freshwater wetlands and rice paddies, their net primary productivity, seasonality and possible methane emissions. J. Atmos. Chem. 1989, 8, 307–358.

- Limpens, J.; Berendse, F.; Blodau, C.; Canadell, J.G.; Freeman, C.; Holden, J.; Roulet, N.; Rydin, H.; Schaepman-Strub, G. Peatlands and the carbon cycle: From local processes to global implications—A synthesis. Biogeosciences 2008, 5, 1475–1491.

- Moore, P.D.; Bellamy, D.J. Peatlands; Elek Science: London, UK, 1974.

- Juottonen, H.; Galand, P.E.; Tuittila, E.S.; Laine, J.; Fritze, H.; Yrjälä, K. Methanogen communities and Bacteria along an ecohydrological gradient in a northern raised bog complex. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 1547–1557.

- Dedysh, S.N.; Pankratov, T.A.; Belova, S.E.; Kulichevskaya, I.S.; Liesack, W. Phylogenetic analysis and in situ identification of Bacteria community composition in an acidic Sphagnum peat bog. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 2110–2117.

- Hartman, W.H.; Richardson, C.J.; Vilgalys, R.; Bruland, G.L. Environmental and anthropogenic controls over bacterial communities in wetland soils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17842–17847.

- Lin, X.; Green, S.; Tfaily, M.M.; Prakash, O.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Corbett, J.E.; Chanton, J.P.; Cooper, W.T.; Kostka, J.E. Microbial community structure and activity linked to contrasting biogeochemical gradients in bog and fen environments of the Glacial Lake Agassiz Peatland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 7023–7031.

- Pankratov, T.A.; Ivanova, A.O.; Dedysh, S.N.; Liesack, W. Bacterial populations and environmental factors controlling cellulose degradation in an acidic Sphagnum peat. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 1800–1814.

- Serkebaeva, Y.M.; Kim, Y.; Liesack, W.; Dedysh, S.N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of the bacteria diversity in surface and subsurface peat layers of a northern wetland, with focus on poorly studied phyla and candidate divisions. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63994.

- Lin, X.; Tfaily, M.M.; Green, S.J.; Steinweg, J.M.; Chanton, P.; Imvittaya, A.; Chanton, J.P.; Cooper, W.; Schadt, C.; Kostka, J.E. Microbial metabolic potential for carbon degradation and nutrient (nitrogen and phosphorus) acquisition in an ombrotrophic peatland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3531–3540.

- Ivanova, A.A.; Wegner, C.E.; Kim, Y.; Liesack, W.; Dedysh, S.N. Identification of microbial populations driving biopolymer degradation in acidic peatlands by metatranscriptomic analysis. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 4818–4835.

- Kotiaho, M.; Fritze, H.; Merilä, P.; Tuomivirta, T.; Väliranta, M.; Korhola, A.; Karofeld, E.; Tuittila, E.S. Actinobacteria community structure in the peat profile of boreal bogs follows a variation in the microtopographical gradient similar to vegetation. Plant Soil 2013, 369, 103–114.

- Juottonen, H.; Kotiaho, M.; Robinson, D.; Merilä, P.; Fritze, H.; Tuittila, E.S. Microform-related community patterns of methane-cycling microbes in boreal Sphagnum bogs are site specific. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91, fiv094.

- Hunger, S.; Gößner, A.S.; Drake, H.L. Anaerobic trophic interactions of contrasting methane-emitting mire soils: Processes versus taxa. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91, fiv045.

- Schmidt, O.; Horn, M.A.; Kolb, S.; Drake, H.L. Temperature impacts differentially on the methanogenic food web of cellulose-supplemented peatland soil. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 17, 720–734.

- Ivanova, A.A.; Beletsky, A.V.; Rakitin, A.L.; Kadnikov, V.V.; Philippov, D.A.; Mardanov, A.V.; Ravin, N.V.; Dedysh, S.N. Closely located but totally distinct: Highly contrasting prokaryotic diversity patterns in raised bogs and eutrophic fens. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 484.

- Cajander, A.K. Studien über die Moore Finnlands (Studies of Finnish mires). Acta For. Fenn. 1913, 2, 1–208. (In Germany)

- Laitinen, J.; Rehell, S.; Huttunen, A.; Tahvanainen, T.; Heikkilä, R.; Lindholm, T. Mire systems in Finland–special view to aapa mires and their water-flow pattern. Suo 2007, 58, 1–26. Available online: http://www.suoseura.fi/Alkuperainen/suo/pdf/Suo58_Laitinen.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Laitinen, J.; Oksanen, J.; Kaakinen, E.; Parviainen, M.; Küttim, M.; Ruuhijärvi, R. Regional and vegetation-ecological patterns in northern boreal flark fens of Finnish Lapland: Analysis from a classic material. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 2017, 54, 179–195.

- Sallinen, A.; Tuominen, S.; Kumpula, T.; Tahvanainen, T. Undrained peatland areas disturbed by surrounding drainage: A large scale GIS analysis in Finland with a special focus on aapa mires. Mires Peat 2019, 24, 38.

- Couwenberg, J. A simulation model of mire patterning—Revisited. Ecography 2005, 28, 653–661.

- Ruuhijärvi, R. The Finnish mire types and their regional distribution. In Mires: Swamp, Bog, Fen and Moor, Ecosystems of the World; Gore, A.J.P., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983; Volume 4B, pp. 47–67.

- Botch, M. Aapa-mires near Leningrad at the southern limit of their distribution. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 1990, 27, 281–286.

- Laitinen, J.; Rehell, S.; Huttunen, A. Vegetation-related hydrotopographic and hydrologic classification for aapa mires (Hirvisuo, Finland). Ann. Bot. Fenn. 2005, 42, 107–121.

- Sirin, A.; Minayeva, T.; Yurkovskaya, T.; Kuznetsov, O.; Smagin, V.; Fedotov, Y. Russian Federation (European Part). In Mires and Peatlands of Europe: Status, Distribution and Conservation; Joosten, H., Tanneberger, F., Moen, A., Eds.; Schweizerbart Science Publishers: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; pp. 589–616.

- Yurkovskaya, T.K. Geography and cartography of mire vegetation of the European Russia and neighbouring territories. Trans. Komar. Botanic. Inst. 1992, 4, 1–256. (In Russian)

- Kutenkov, S.A.; Philippov, D.A. Aapa mire on the southern limit: A case study in Vologda Region (north-western Russia). Mires Peat 2019, 24, 1–24.

- Tzvelev, N.N. Guide to the Vascular Plants of the Northwestern Russia (Leningrad, Pskov and Novgorod Regions); Chemical-Pharmaceutical Academy Press: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2000. (In Russian)

- Seward, J.; Carson, M.A.; Lamit, L.J.; Basiliko, N.; Yavitt, J.B.; Lilleskov, E.; Schadt, C.W.; Smith, D.S.; Mclaughlin, J.; Mykytczuk, N.; et al. Peatland microbial community composition is driven by a natural climate gradient. Microb. Ecol. 2020, 80, 593–602.

- Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Waite, D.W.; Rinke, C.; Skarshewski, A.; Chaumeil, P.A.; Hugenholtz, P. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 996–1004.