Species of Franklinothrips (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae) are predatory on various other insects. These fast moving, ant-mimicking predatory thrips are widely distributed in the tropics. F. vespiformis has gained attention for its potential as a biocontrol agent for a diverse range of greenhouse pests, and it has already been commercially cultured in Europe for certain use.

- ant-mimic

- demography

- habitat

- Franklinothrips

- prey specificity

- predatory thrips

1. Introduction

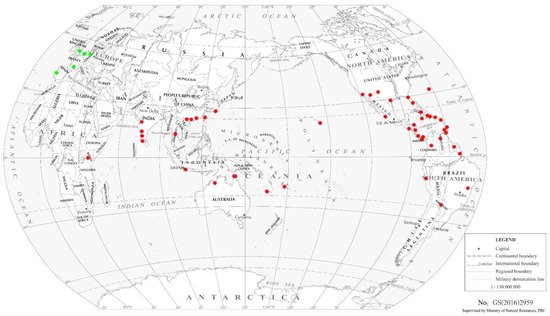

2. Distribution

2.1. F. vespiformis

2.2. Other Franklinothrips Species

3. Morphological Characteristics

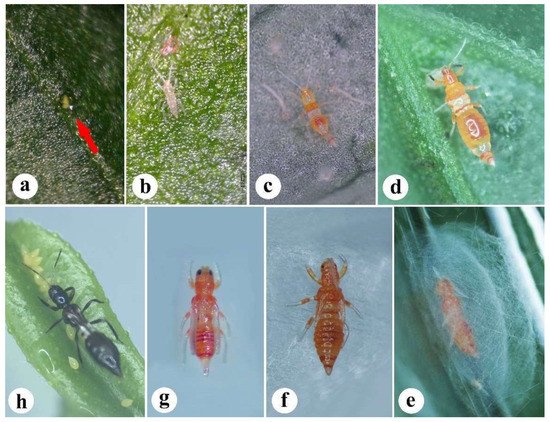

3.1. Eggs

3.2. Larva

3.3. Pupa

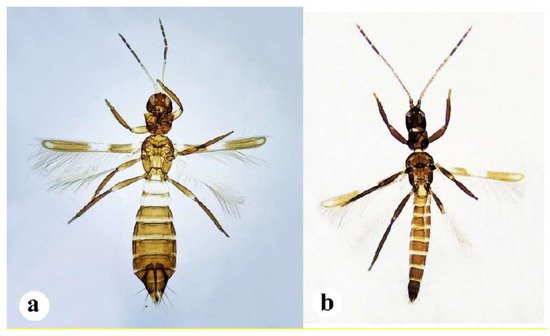

3.4. Adult Female

3.5. Adult Male

4. Life History

4.1. Developmental Parameters

|

Development Parameter |

Temperature (°C) |

Reference(s) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

21 °C |

25 °C |

27 °C |

||||

|

Life Stage (Days (±SE)) |

||||||

|

Eggs |

16.06 ± 0.8 |

10.39 ± 0.1 |

9.7 ± 0.0 |

|||

|

Larva 1 |

4.04 ± 0.12 |

2.03 ± 0.0 |

1.9 ± 0.0 |

|||

|

Larva 2 |

3.9 ± 0.1 |

2.1 ± 0.0 |

1.1 ± 0.0 |

|||

|

Prepupal and Pupal |

12.5 ± 0.1 |

7.4 ± 0.1 |

5.3 ± 0.0 |

|||

|

Unmated Males |

24.3 ± 1.6 |

16.4 ± 1.3 |

9.0 ± 0.7 |

|||

|

Mated Males |

15.6 ± 1.9 |

12.8 ± 1.6 |

8.0 ± 0.6 |

|||

|

Central America |

Costa Rica, El Salvador, Nicaragua |

|||||

|

Reproductive parameter (±SE) | [ | |||||

|

Unmated Females |

Honduras |

[ |

28] |

|||

|

Pre-oviposition period (days) |

Panama |

1.6 ± 0.2 [14] |

||||

0.9 ± 0.2 |

2.4 ± 1.0 |

South America |

||||

|

Mean total progeny |

Brazil |

67.9 ± 21.4 |

||||

71.2 ± 12.9 |

8.5 ± 3.8 |

Paraguay |

[ | |||

|

Mean daily progeny |

2.3 ± 0.2 | 24] |

||||

4.1 ± 0.3 |

1.0 ± 0.1 |

|||||

|

Mean lifetime oviposition rate |

Peru (Miraflores) |

[ |

154 ± 22.414] |

|||

314 ± 44.1 |

105 ± 17.9 |

Surinam | ||||

|

Mean daily oviposition rate |

7.1 ± 0.4 |

|||||

18.1 ± 13.6 |

12.9 ± 1.3 |

Asia |

||||

|

Mated Females |

China (Taiwan) |

[32 |

] |

|||

|

Pre-oviposition period (days) |

China (Guangdong Yunnan, Guangxi) |

1.5 ± 0.2 [11] |

||||

0.9 ± 0.1 |

0.8 ± 0.2 |

India (Karnataka, Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu) |

||||

|

Mean total progeny | [33][ |

35.2 ± 6.634] |

||||

44.4 ± 11.8 |

8.4 ± 2.8 |

Indonesia (Java) | ||||

|

Mean daily progeny |

[35] |

|||||

1.8 ± 0.1 |

3.1 ± 0.2 |

0.9 ± 0.2 |

||||

|

Mean lifetime oviposition rate |

Japan (Okinawa) |

128 ± 25.5 |

||||

220 ± 47.9 |

101 ± 14.7 |

|||||

|

Mean daily oviposition rate |

Thailand |

6.5 ± 0.5 | ||||

15.9 ± 1.1 |

12.8 ± 1.1 |

Oceania |

Australia (Queensland) |

|||

|

Population growth parameters (±SE) | [10] |

|||||

|

Net reproductive rate (R |

New Caledonia |

0) [ |

18.5 ± 0.18 10] |

|||

33.3 ± 0.28 |

4.5 ± 0.07 |

|||||

|

Generation time (Tc) |

Hawaii |

[24] |

||||

49.1 ± 0.12 |

27.9 ± 0.05 |

24.2 ± 0.06 |

Europe |

|||

|

Intrinsic rate of increase (r |

France |

m) 0.06 ± 0.0002 |

||||

0.13 ± 0.0003 |

0.06 ± 0.0007 |

|||||

|

Finite rate of increase (λ) |

Germany |

1.06 ± 0.0002 [41] |

||||

1.14 ± 0.0004 |

1.07 ± 0.0007 |

Portugal |

||||

|

Survival time in days (Td) |

11.12 ± 0.03 | [24] |

||||

5.16 ± 0.01 |

11.05 ± 0.12 |

UK |

||||

4.2. Sex Ratio

4.3. Ovipositing Behavior

4.4. Cocoon Spinning

4.5. Ant-Mimicking Behavior

References

- ThripsWiki. Providing information on the World’s thrips (version Nov 2018). In Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life, 2019 Annual Checklist; Roskov, Y., Ower, G., Orrell, T., Nicolson, D., Bailly, N., Kirk, P.M., Bourgoin, T., DeWalt, R.E., Decock, W., Nieukerken, E., et al., Eds.; Naturalis: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; Available online: www.catalogueof-life.org/annual-checklist/2019 (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Parker, B.; Skinner, M.; Ewis, T. (Eds.) Thrips Biology and Management; NATO ASI Series. Life Science; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; Volume 276.

- Riley, D.G.; Joseph, S.V.; Srinivasan, R.; Diffie, S. Thrips vectors of tospoviruses. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2011, 2, I1–I10.

- Morse, J.G.; Hoddle, M.S. Invasion biology of thrips. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2006, 51, 67–89.

- Reynaud, P. Thrips (Thysanoptera). Chapter 13.1. BioRisk 2010, 4, 767.

- zur Strassen, R. Binomial data of some predacious thrips. In Thrips Biology and Management; Parker, B., Skinner, M., Ewis, T., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 325–328.

- Saengyot, S. Predatory thrips species composition, their prey and host plant association in Northern Thailand. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2016, 50, 380–387.

- Parrella, M.; Rowe, D.; Horsburgh, R. Biology of Leptothrips mali, a common predator in Virginia apple orchards. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1982, 75, 130–135.

- Haviland, D.R.; Rill, S.M.; Gordon, C.A. Field biology of Scolothrips sexmaculatus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) as a predator of Tetranychus pacificus (Acari: Tetranychidae) in California almonds. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 1111–1116.

- Mound, L.A.; Reynaud, P. Franklinothrips; a pantropical Thysanoptera genus of ant-mimicking obligate predators (Aeolothripidae). Zootaxa 2005, 864, 1–16.

- Mirab-Balou, M.; Shi, M.; Chen, X.-X. A new species of Franklinothrips Back (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae) from Yunnan, China. Zootaxa 2011, 2926, 61–64.

- Reyne, A. A Cocoonspinning Thrips. Tijdschr. Voor Entomol. 1920, 63, 40–45.

- Pereyra, V.; Cavalleri, A. The genus Heterothrips (Thysanoptera) in Brazil, with an identification key and seven new species. Zootaxa 2012, 3237, 1–23.

- Goldarazena, A.; Gattesco, F.; Atencio, R.; Korytowski, C. An updated checklist of the Thysanoptera of Panama with comments on host associations. Check List 2012, 8, 1232–1247.

- Larentzaki, E.; Powell, G.; Copland, M.J. Effect of cold storage on survival, reproduction and development of adults and eggs of Franklinothrips vespiformis (Crawford). Biol. Control 2007, 43, 265–270.

- Larentzaki, E.; Powell, G.; Copland, M.J. Effect of temperature on development, overwintering and establishment potential of Franklinothrips vespiformis in the UK. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2007, 124, 143–151.

- Hoddle, M.S.; Oevering, P.; Phillips, P.A.; Faber, B.A. Evaluation of augmentative releases of Franklinothrips orizabensis for control of Scirtothrips perseae in California avocado orchards. Biol. Control 2004, 30, 456–465.

- Mahaffey, L.A.; Cranshaw, W.S. Thrips species associated with onion in Colorado. Southwest. Entomol. 2010, 35, 45–50.

- Stannard, L.J., Jr. Peanut-winged thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1952, 45, 327–330.

- Stannard, L.J. Phylogenetic studies of Franklinothrips (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae). J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 1952, 42, 14–23.

- Hoddle, M.S.; Mound, L.A.; Paris, D.L. Thrips of California; CBIT Publishing: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2012; Available online: https://keys.lucidcentral.org/keys/v3/thrips_of_california/Thrips_of_California.html (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Crawford, D. Some Thysanoptera of Mexico and the south. I. Pomona Coll. J. Entomol. 1909, 1, 109–119.

- Cambero-Campos, J.; Johansen-Naime, R.; García-Martínez, O.; Cerna-Chávez, E.; Robles-Bermúdez, A.; Retana-Salazar, A. Species of thrips (Thysanoptera) in avocado orchards in Nayarit, Mexico. Fla. Entomol. 2011, 94, 982–986.

- CABI. Invasive Species Datasheet, Franklinothrips vespiformis (Vespiform Thrips). 2021. Available online: https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/24485 (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Greathead, D.J.; Greathead, A.H. Biological control of insect pests by insect parasitoids and predators: The BIOCAT database. Biocontrol 1992, 13, 61N–68N.

- Callan, E.M. Natural enemies of the cacao thrips. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1943, 34, 313–321.

- Williams, C. Plant diseases and pests: Notes on some Trinidad thrips of economic importance. Trinidad Tobago Bull. 1918, 3, 143–146.

- Watson, J.; Hubbell, T. On a collection of Thysanoptera from Honduras. Fla. Entomol. 1924, 7, 60–62.

- Moulton, D. The Thysanoptera of South America. Revta Entomol. 1932, 2, 464–465.

- de França, S.M.; de Melo Júnior, L.C.; Neto, A.V.G.; Silva, P.R.R.; Lima, É.F.B.; Melo, J.W.S. Natural enemies associated with Phaseolus lunatus L. (Fabaceae) in Northeast Brazil. Fla. Entomol. 2018, 101, 688–691.

- Lima, E.F.B.; Souza-Filho, M.F. Leucothrips furcatus (Thysanoptera Thripidae): A new pest of Sechium edule (Cucurbitaceae) in Brazil. Bull. Insectol. 2018, 71, 189–191.

- Wang, C.-L. Two new records and two new species of thrips (Thysanoptera, Terebrantia) of Taiwan. Chin. J. Entomol. 1993, 13, 251–257.

- Tyagi, K.; Kumar, V. Thrips (Insecta: Thysanoptera) of India-an updated checklist. Halteres 2016, 7, 64–98.

- Mahendran, P.; Radhakrishnan, B. Franklinothrips vespiformis Crawford (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae), a potential predator of the tea thrips, Scirtothrips bispinosus Bagnall in south Indian tea plantations. Entomon 2019, 44, 49–55.

- Sartiami, D.; Mound, L.A. Identification of the terebrantian thrips (Insecta, Thysanoptera) associated with cultivated plants in Java, Indonesia. ZooKeys 2013, 306, 1–21.

- Arakaki, N.; Okajima, S. Notes on the biology and morphology of a predatory thrips, Franklinothrips vespiformis (Crawford) (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae): First record from Japan. Entomol. Sci. 1998, 1, 359–363.

- Pijnakker, J.; Overgaag, D.; Guilbaud, M.; Vangansbeke, D.; Duarte, M.; Wäckers, F. Biological control of the Japanese flower thrips Thrips setosus Moulton (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in greenhouse ornamentals. IOBC-WPRS Bull. 2019, 147, 107–112.

- Pizzol, J.; Nammour, D.; Hervouet, P.; Poncet, C.; Desneux, N.; Maignet, P. Population dynamics of thrips and development of an integrated pest management program using the predator Franklinothrips vespiformis. In Proceedings of the XXVIII International Horticultural Congress on Science and Horticulture for People (IHC2010), Lisbon, Portugal, 22–27 August 2010; pp. 219–226.

- Pizzol, J.; Nammour, D.; Ziegler, J.-P.; Voisin, S.; Maignet, P.; Olivier, N.; Paris, B. Efficiency of Neoseiulus cucumeris and Franklinothrips vespiformis for controlling thrips in rose greenhouses. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on High Technology for Greenhouse System Management: Greensys 2007, Naples, Italy, 4–6 October 2007; Volume 801, pp. 1493–1498.

- Loomans, A.; Vierbergen, G. Franklinothrips: Perspectives for greenhouse pest control. IOBC WPRS Bull. 1999, 22, 157–160.

- Zegula, T.; Sengonca, C.; Blaeser, P. Entwicklung, reproduktion und Prädationsleistung von zwei Raubthrips-arten Aeolothrips intermedius Bagnall und Franklinothrips vespiformis Crawford (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae) mit ernährung zweier natürlicher beutearten. Gesunde Pflanz. 2003, 55, 169–174.

- Cox, P.; Matthews, L.; Jacobson, R.; Cannon, R.; MacLeod, A.; Walters, K. Potential for the use of biological agents for the control of Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) outbreaks. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2006, 16, 871–891.

- Hoddle, M.S. Predation behaviors of Franklinothrips orizabensis (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae) towards Scirtothrips perseae and Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Biol. Control 2003, 27, 323–328.

- Tyagi, K.; Mound, L.; Kumar, V. Sexual dimorphism among Thysanoptera Terebrantia, with a new species from Malaysia and remarkable species from India in Aeolothripidae and Thripidae. Insect Syst. Evol. 2008, 39, 155–170.

- Kumar, B. Thrips. In Polyphagous Pests of Crops; Omkar, Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 373–407.

- Arakaki, N.; Miyoshi, T.; Noda, H. Wolbachia-mediated parthenogenesis in the predatory thrips Franklinothrips vespiformis (Thysanoptera: Insecta). Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2001, 268, 1011–1016.

- Kumm, S.; Moritz, G. First detection of Wolbachia in arrhenotokous populations of thrips species (Thysanoptera: Thripidae and Phlaeothripidae) and its role in reproduction. Environ. Entomol. 2008, 37, 1422–1428.

- Nguyen, D.T.; Spooner-Hart, R.N.; Riegler, M. Loss of Wolbachia but not Cardinium in the invasive range of the Australian thrips species, Pezothrips kellyanus. Biol. Invasions 2016, 18, 197–214.

- O’Neill, K. Identification of the Newly Introduced Phlaeothripid Haplothrips? Clarisetis Priesner (Thysanoptera). Ann. Ent Soc. Am. 1960, 53, 507–510.

- Pal, S.; Wahengbam, J.; Raut, A.; Banu, A.N. Eco-biology and management of onion thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). J. Entomol. Res. 2019, 43, 371–382.

- Putman, W.L. Notes on the predaceous thrips Haplothrips subtilissimus hal. and Aeolothrips melaleucus Hal. Can. Entomol. 1942, 74, 37–43.

- Johansen, R.M. Algunos aspectos sobre la conducta mimetic de Franklinothrips vespiformis (Crawford (Insecta: Thysanoptera)). An. Instit. Biol. Univ. Nac. Mex. 1977, 47, 45–52.

- Johansen, R.M. Nuevos estudios acerca del mimetismo en el genero Franklinothrips Back (Insect: Thysanoptera) en Mexico. An. Inst. Biol. Univ. Nac. Mex. 1983, 53, 133–156.