Fish is a major source of food and nutritional security for subsistence communities in developing countries, it also has linkages with the economic and supply-chain dimensions of these countries. It This entry revealeds that COVID-19 has posed numerous challenges to fish supply chain actors, including a shortage of inputs, a lack of technical assistance, an inability to sell the product, a lack of transportation for the fish supply, export restrictions on fish and fisheries products, and a low fish price. These challenges lead to inadequate production, unanticipated stock retention, and a loss in returns. COVID-19 has also resulted in food insecurity for many small-scale fish growers. Fish farmers are becoming less motivated to raise fish and related products as a result of these cumulative consequences. Because of COVID-19’s different restriction measures, the demand and supply sides of the fish food chain have been disrupted, resulting in reduced livelihoods and economic vulnerability.

- aquaculture

- small-scale fisheries

- fish-based industry

- fish-food supply chain

- agri-food system

- fish farming

- agricultural vulnerability

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has had an influence on all sectors of the economy; the fisheries and aquaculture sector in particular has faced great difficulty, mainly due to the perishability of the product [1][2].

Fish is often a fishing community’s primary source of protein, fatty acids, and micronutrients [2][3]. Fish do not play a role in the transfer of COVID-19 to humans in terms of epidemiology. However, false perceptions about fish and the spread of COVID-19 have contributed to a decrease in the consumption of fish in some cases, such as in Bangladesh and China [3][4]. Because fish is an important food source for a large portion of the world’s population, the business of fishing requires changes, especially now during the current pandemic. Many of the governmental measures that have been introduced to limit the spread of COVID-19 have caused significant disruptions to human movement, physical business contact and the transport of goods [4][5]. M

By disrupting fish supply and demand, fish distribution, labor, and production, COVID-19 exposes the existing vulnerabilities in small-scale fisheries, putting small-scale farmers’ livelihoods at risk [5][7]. The many value chains within the fisheries and aquaculture sector were also subject to the inevitable disruptions to international and domestic transportation; these disruptions have affected the supply of raw materials for processing, the supply of production inputs, and the shipping of the finished products for both export and domestic consumption [6][8]. Farm-made inputs, such as seed stock and feed, have become unavailable due to the stringent restrictions that have been placed on the movement of materials and persons, including workers [7][9]. Small-scale fish farmers have lost money because they either had to sell off their fish or couldn’t sell their fish at all. Fish farmers could not harvest their fish in order to be able to begin a new production cycle, leading to a reduction in fish availability and the loss of downstream and upstream employment opportunities [5][7]. According to Waiho et al. [8][10], COVID-19 has depressed the demand for fish and fishery products and negatively impacted the supply chain, forcing hatcheries to close, feed imports to halt, and many value chain entities to lose money right from the start of the culture season. Medium and small businesses and seafood producers have been hit particularly hard, many of them are still unable to resume their normal operations [9][11]. COVID-19, in fact, has posed complex and long-term challenges for the aquaculture value chains’ continued operations and the livelihoods of the millions of people who rely on them [10][12]. However, the major impact on supply chains and demand is not from COVID-19 itself, but instead from the measures that have been introduced in order to control it.

2. Summary of the Impacts of COVID-19 on the Fisheries Sector

| Major Domains of Fisheries and Aquaculture Production | Impacts of COVID-19 | Sources |

|---|

3. COVID-19’s Impacts on the Aquatic Food Supply Chain

The present study has identified several of the major impacts of COVID-19 on the aquatic food supply chain (Table 23). The key domains that have been affected are fishing, aquaculture production, processors and cold storage. At the fishing level, farmers are facing limited access to capture fisheries, less time to catch the fish, expensive labor, and travel restrictions. Similarly, at the production level, stakeholders are experiencing the higher costs of inputs and transportation, less demand, reductions in the price of the product, and undesired stock. At the processor level, there are also several challenges such as expensive transportation, dropping demand and prices, expensive inputs and restrictions on transportation (Table 23). The aquatic food supply chain’s stakeholders are also facing limited access to cold storage facilities and are therefore incurring losses due to the perishability of the product.| Major Domains of Supply Chain | Impacts of COVID-19 | Sources | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders |

| ||||||||||||

| Fishing |

|

| Belton [13] Stokes et al. |

Fiorella et al. [18][10] Ferrer et al. Campbell et al. [30][7] Kumaran et al. [14] | Belton [31] Stokes et al. [12] Ferrer et al. [9] Kumaran et al. [32] |

||||||||

| Ruiz-Salmón et al. | [31] Paradis et al. [29] | Fiorella et al. [6] Campbell et al. [20] Ruiz-Salmón et al. [26] Paradis et al. [44] |

Freshwater aquaculture |

| |||||||||

| Aquaculture production |

|

|

| Islam et al. [15] Seshagiri et al. [16] Cooke et al. [17] Fiorella et al. [18] Stokes et al. [10] | Islam et al. [18] Seshagiri et al. [33] Cooke et al. [34] Fiorella et al. [6] Stokes et al. [12] |

||||||||

| Cooke et al. | [ | 17] Manlosa et al. [19] Sarà et al. [32] Islam et al. [15] | Cooke et al. [34] Manlosa et al. [35] Sarà et al. [22] Islam et al. [18] |

Brackish water aquaculture |

|

Islam et al. [15] Manlosa et al. [19] | Kumaran et al. [32] Islam et al. [ | ||||||

| Processors | 18 | ] Manlosa et al. [35] |

|||||||||||

| White et al. [33] Bennett et al. [34] Fiorella et al. [18] Kumaran et al. [14] | White et al. [46] Bennett et al. [47] Fiorella et al. [6] Kumaran et al. [32] |

River and naturally sourced fisheries |

| |||||||||

| Cold storage facilities |

| Waibel et al. [20] Newton et al. [21] Islam et al. [15] Stokes et al. [10] | Waibel et al. [36] Newton et al. [14] Islam et al. [18] Stokes et al. [12] |

||||||||||

| Fahlevi et al. | [ | 35] Kumaran et al. [14] Kaewnuratchadasorn et al. | Fahlevi et al. [48 | [28 | ] Kumaran et al. [32 | ] | ] Kaewnuratchadasorn et al. [43] |

Offshore fisheries |

| Andrews et al. [22] Shenoy & Rajpathak [23] Marschke et al. [24] Asante, & Sabau [25] | Andrews et al. [37] Shenoy & Rajpathak [38] Marschke et al. [39] Asante, & Sabau [40] |

||

| Industry |

| Fernández-González, & Pérez-Vas [26] Hasan et al. [27] Kaewnuratchadasorn et al. [28] Paradis et al. [29] | Fernández-González, & Pérez-Vas [41] Hasan et al. [42] Kaewnuratchadasorn et al. [43] Paradis et al. [44] |

4. Impacts on Fisheries’ Production and Activity

4.1. The Negative Impacts

- Impact on fishing activity

- Impact on fishing activity

Fishing activity has decreased as a result of the social distancing practices and additional COVID-19 restrictions that have been implemented [15][18]. Since the World Health Organization proclaimed COVID-19 to be a pandemic, global industrial fishing activities have decreased by 10% or more in some areas, relative to the previous year’s average [2][3]. Fisheries were outlawed in several nations, such as India, as part of the mobility limitations that were imposed to counteract the developing pandemic [34][47].

- Impacts on aquaculture farms

Due to the significant drop in the market’s demand for fish and the limited transportation options that were available during the lockdown, fish farms have had difficulty in collecting and selling their goods [1][2]. As farmers have been unable to sell their products there has been an increase in live fish stock levels and a lengthening of the fish culture period, both of which have negatively impacted the feed conversion ratios, the ability to restock and, ultimately, the farms’ profitability.

4.2. Common Challenges Faced by Small-Scale Fisheries

5. Disruption to the Aquatic Food Supply Chain

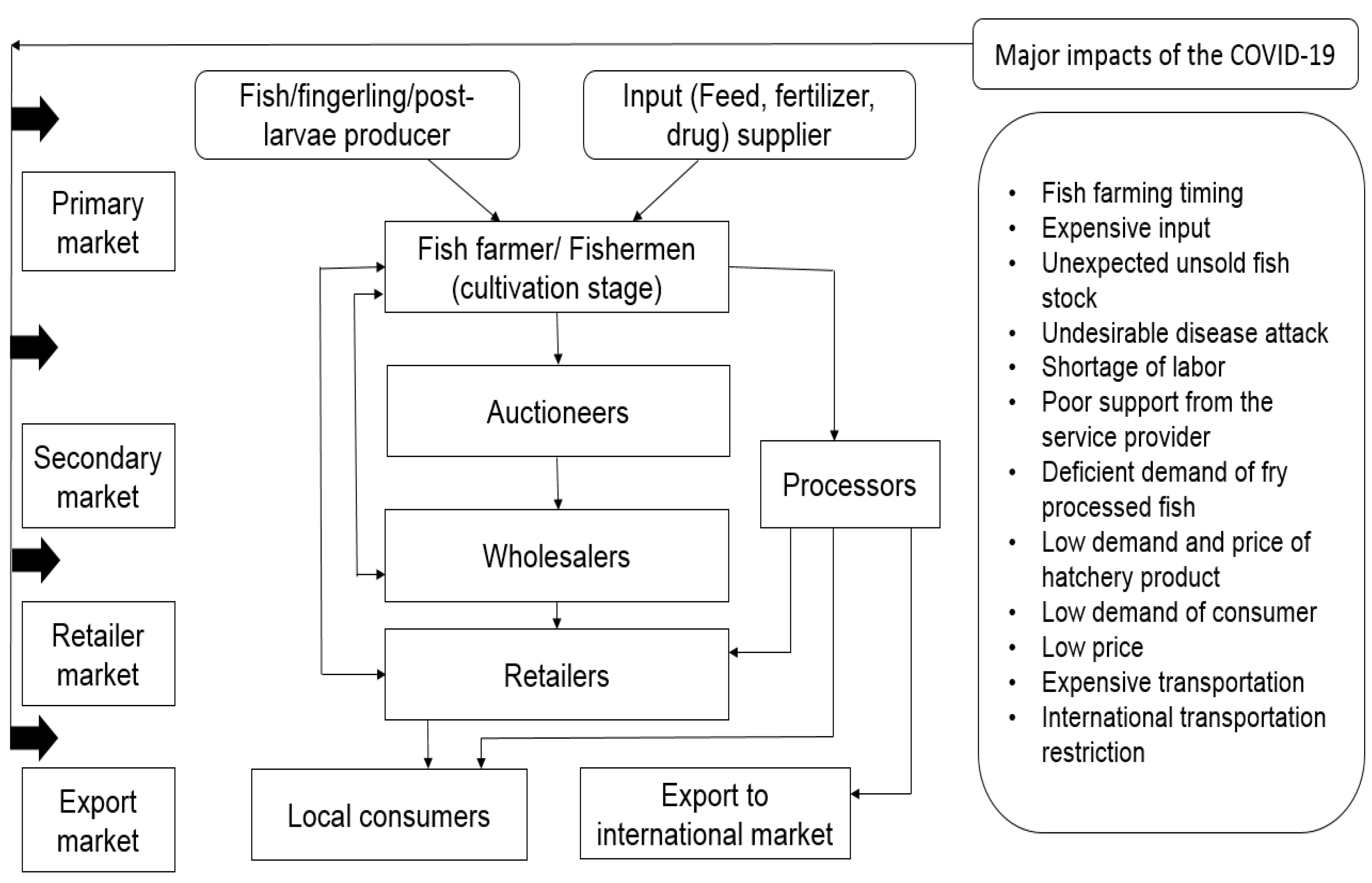

Global, regional, and local markets are all a part of the aquatic food supply chain. The operations required to transport fish and fish products from the supplier to the end consumer are extensive. Across the globe, the technologies used for this purpose range from traditional to highly industrial. The effects of COVID-19 have affected every activity in the supply chain (Figure 12). Within Figure 12, the bold arrows on the left side show the main points at which COVID-19 impacts the primary, secondary, retailer and export markets.

65. Policy Recommendations

- Smallholder fishers, whose livelihoods have been most heavily impacted by COVID-19, need food and cash for their survival and continued production. Loan forgiveness or new loans at subsidized rates for small-scale fishers and farmers could be included in the provision.

- The restoration of the fishing sector, including fishing activities, production, processing, and trade, can be aided by an emergency relief loan.

- The resumption of fresh product and seafood processing necessitates a relevant national agency’s safety and health inspection certification. Health and safety regulations must be implemented for fisheries’ products and processing facilities.

- The inability of smallholder fishers to sell their produce during the COVID-19 pandemic warrants the strengthening of the fish value chains, including the development of road and market infrastructure, cold storage facilities, transport systems, farmer to market linkages, and the increased flow of market information.

- The process of gaining knowledge from the losses and damages that have been incurred must be supported across all relevant institutions and sectors.

- Development organization can help with the re-orientation and flexibility of financing programs and the targeting of support to smallholders and rural fishing communities.

- The fishing season could be extended on a conditional basis.