Chronic placental inflammatory (CPI) lesions include chronic villitis of unknow etiology (CVUE), chronic intervillositis of unknown etiology, CIUE (also described as chronic histiocytic intervillositis, CHI), and chronic deciduits. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) has been prescribed with good results during pregnancy to prevent adverse perinatal outcomes in maternal autoimmune conditions. Its success has paved the way to its use in CPI as CIUE/CHI.

1. Introduction

Considered central to chronic disease development

[1], placental phenotype arrangement is thought to determine chronic adult-onset disease. Unbalanced maternal nutrition, periods of chronic hypoxia or increased levels of glucocorticoids or thyroid hormones determine fetal structural alterations such as reduced blood vessel diameter

[2], low arterial elastin

[3], reduced numbers of nephrons in the kidney

[4], reduced number of beta cells in the pancreas

[5], and changes in brain structure and function

[6] that increase the vulnerability for heart disease, stroke, obesity, and diabetes later in adult life.

The placenta is the site of connection between maternal and fetal circulation and the liaison is established early in pregnancy, when placentation occurs. Therefore, a large variety of pregnancy complications have placental expression. Inflammatory placental conditions with acute or chronic onset have specific immunological mechanisms and carry a significant short- and long-term response in fetal development with an increased recurrence rate for subsequent pregnancies. Acute placental inflammation, as seen on microscopical preparations, is associated to chorioamnionitis

[7]. The origin of chorioamnionitis includes amniotic fluid infection, intrauterine infection, or ascending infection

[8]. Bacteria are rarely identified at term

[9], but more frequently identified in preterm deliveries when acute inflammation of the placenta and clinical signs of chorioamnionitis are present

[10]. Forces of labor themselves

[11] and maternal comorbidities (obesity)

[12] induce inflammation that may be reflected in the placenta. Chronic placental inflammation (CPI) lesions involve specific cells, such as lymphocytes and histiocytes and have a particular location in the placenta

[13]. They may be associated with autoimmune disorders or persistent infection, or may be of unknown etiology. Chronic inflammation decreases the healthy tissue involved in uteroplacental circulation and is linked to severe obstetric complications such as fetal growth restriction (FGR), preterm birth (PTB), and pregnancy loss

[14]. Chronic inflammation of the placenta can be suspected during pregnancy if complications such as recurrent miscarriage, stillbirth, or FGR develop, but confirmation is only made after delivery in a histopathological exam

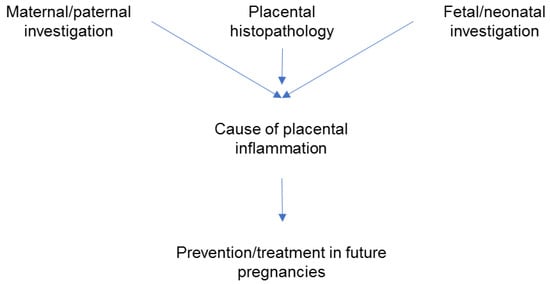

[14]. The clinical approach is to look for a cause of the placental inflammation by combining information provided by the pathology exam and the investigations performed in the mother, father, fetus, or neonate. Discovering a cause is important for subsequent pregnancies management (

Figure 1) since some forms of CPI are recurrent

[14].

Figure 1. Steps in the clinical management of adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with placental inflammation; the focus is on prevention in subsequent pregnancies.

A better understanding of the chronic inflammatory process in the placenta is needed in view of possible methods of treatment, prevention, and better pregnancy outcomes. Various drugs have been tried with mixed success rates to improve outcomes in subsequent pregnancies after demonstration of CPI in histological specimens: steroids, aspirin, low molecular weight heparin, and intravenous immunoglobulins

[15][16][17][18][15,16,17,18].

The antimalarial agent hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) has emerged as a safe drug to be used during pregnancy for preventing adverse outcomes in mothers with autoimmune conditions

[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], where its beneficial effect is considered to outweigh the potential risks to the fetus. This has encouraged taking it into consideration for prevention of recurrent CPI lesions

[27]. However, caution should be exerted whenever a drug is used with new indications without properly conducted research. Hydroxychloroquine in particular was the drug involved in the so called “hype-based medicine” for treatment of COVID-19 infections in 2020

[28].

2. Types of Chronic Placental Inflammation

The Amsterdam classification system defines four major patterns of placental injury: maternal vascular malperfusion, fetal vascular malperfusion, acute chorioamnionitis, and villitis of unknown etiology [8].

The histological analyses may reveal areas of inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasmocytes aggregated within the placenta sometimes with a particular specific location and specific genotypes and phenotypes [29][30][31][34,35,36].

Table 1. Chronic placental inflammation—classification.

|

|

-

Chronic placenta inflammation associated with specific maternal infections

(COVID-19, cytomegalovirus, Treponema pallidum, HIV, Zika).

|

|

|

| |

|

It is considered that CPI may be related to failure of the maternal tolerance to fetal antigens and with maternal immune system activation; however, the complete pathogenesis is not completely understood

[29][34].

In chronic villitis of unknown etiology (CVUE) maternal immune rejection of a semi allogeneic placenta is thought to be a mechanism

[16]. In patients with recurrent pregnancy loss, the prevalence is reaching 8% and the recurrence in subsequent pregnancies ranges from 18% to 100%

[32][31]. Chronic villitis of unknown etiology involves a large infiltration of mainly placental terminal villi by lymphocytes and histiocytes, as well as, less commonly, plasma cells. The cell aggregation is characterized by destruction of capillaries resulting in poor uteroplacental circulation. A field that requires further investigation and studies is the treatment of subsequent pregnancies after a pregnancy loss that demonstrates the presence of chronic villitis of unknown etiology. Treatment with acetylsalicylic acid, heparin, steroids, and hydroxychloroquine has been reported with mixed outcomes

[15][16][15,16].

3. Pregnancy Complications Associated with Chronic Placental Inflammation

All forms of chronic placental inflammation have possible associations with poor obstetric outcomes

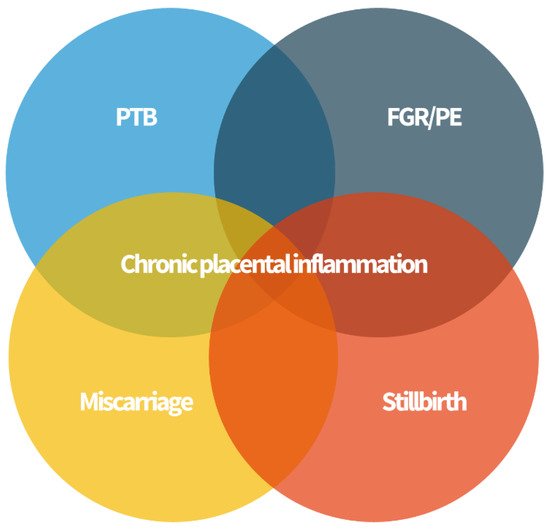

[29][34]. Complications such as PTB, FGR and neurocognitive and development disorders, recurrent miscarriage, stillbirth, and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (NAIT) have been associated with inflammation of the placenta of unknown etiology after a careful histopathological analysis (

Figure 2).

Figure 2. Chronic placenta inflammation is found in some cases of preterm birth (PTB), fetal growth restriction (FGR) and preeclampsia (PE), miscarriage, and stillbirth. These “great obstetrical syndromes” may share a common pathophysiology.

Chronic villitis of unknown etiology and chronic deciduitis with plasma cells have been associated with preterm labor, but the inflammatory process has not been considered as an independent risk factor for long-term outcomes

[29][34]. Acute chorioamnionitis remains the most common cause associated with early PTB considered less than 28 weeks, and chronic chorioamnionitis is most frequently associated with late preterm birth between 34 and 37 weeks

[33][38].

In terms of FGR, CVUE have been associated with poor fetal growth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age fetuses with rates of 70%

[34][32]. Follow-up in children with FGR from pregnancies with histological expression of CVUE demonstrated an increased risk of low developmental index at 2 years of age and increased risk of cerebral palsy and abnormal neurodevelopmental findings in term infants

[35][39].

Sadly, many cases of histological diagnosis of chronic placental inflammation were associated with stillbirth and recurrent pregnancy loss

[29][34]. Chronic intervillositis of unknown etiology (CIUE) is strongly associated with miscarriage, intrauterine fetal demise, and a very high risk of recurrence

[36][42].

In pregnancies complicated by the “great obstetrical syndromes” the placenta should always be sent for examination to a specialized pathologist (placenta pathologist or perinatal pathologist).

4. Hydroxychloroquine in Pregnancy

4.1. HCQ Used in Pregnancy to Improve Outcomes in Women with Autoimmune Conditions

Hydroxychloroquine is an antimalarial agent firstly described in 1955 that has an anti-inflammatory and immunomodulator effect, showing a complex mechanism of action. It increases intracellular pH within intracellular vacuoles, and it has been demonstrated that it alters various processes such as protein degradation by acidic hydrolases in the lysosome, assembly of macromolecules in the endosomes, and post-translation modification of proteins in the Golgi apparatus

[37][43]. It has also been suggested that HCQ is involved in phagocytosis, proteolysis, antigen presentation, and chemotaxis, decreasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins, inhibiting of matrix metalloproteinases, and blocking T- and B-cell receptor and toll-like receptor signaling

[38][44]. Additionally, HCQ has lipid lowering, anticoagulant, and antidiabetic effects that may take part in reducing high cardiovascular risk in autoimmune diseases

[39][45]. Regarding possible effects on trophoblastic placental tissue, recent studies have shown HCQ to partially reverse antiphospholipid antibody-induced inhibition of trophoblast migration and to restore the diminished trophoblast fusion and function

[40][46].

Hydroxychloroquine is prescribed for inflammatory conditions associated with adverse perinatal outcome such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS), and placental inflammatory lesions such as CIU/CHI

[41][47].

With regards to safety of HCQ in pregnancy, studies from the literature have suggested no hydroxychloroquine-related adverse effects on the fetus

[20][42][43][44][45][46][47][20,50,61,62,63,64,65], with the exception of one meta-analysis that showed an increased rate of spontaneous pregnancy when HCQ was administered in the first weeks of pregnancy

[48][66].

Hydroxychloroquine exerts a strong and persistent anti-inflammatory response at the level of trophoblastic tissue, as previously studied in excessive inflammation that causes placental insufficiency in antiphospholipid syndrome-complicated pregnancies

[49][71]. Antiphospholipid syndrome is described by circulating antiphospholipid antibodies that determine an excessive inflammatory response and increase the chance of adverse pregnancy complication, such as recurrent pregnancy loss, preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome (hemolytic anemia, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet counts), intrauterine growth restriction, and premature delivery. Albert et al.

[49][71] showed that hydroxychloroquine partially antagonizes the inhibition of trophoblast migration from antiphospholipid syndrome, possibly through the modulation of IL-6 production, and may prevent Toll-like receptor 4-dependent trophoblast inflammatory cytokine response.

4.2. Hydroxychloroquine in Chronic Histiocytic Intervillositis (CHI)

A study from the Children’s and Women’s Hospital in Vancouver, BC, Canada [50][72], reports various empiric treatment in patients with previous diagnosis of CIUE/CHI. One of the options of treatment was HCQ with a dosage ranging between 200 and 400 mg PO daily. It was started pre-pregnancy or with a positive pregnancy test and continued until pregnancy loss or delivery. None of the cases of pregnant women treated with HCHQ developed retinopathy, a rare complication from hydroxychloroquine use. In patients with CIUE/CHI, serum alkaline phosphatase was increased 2.5 times as compared to normal values, and it may be a potential marker that can be followed in subsequent pregnancies [51][73].