PAS kinase (PASK) is a serine/threonine kinase containing an N-terminal Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain, able to detect redox state. It is a nutrient sensor and during fasting/feeding changes, PASK regulates the expression and activation of critical liver proteins involved in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis.

- oxidative stress

- metabolic sensors

- nutritional states

- reactive oxygen species

- antioxidant enzymes

- obesity

- diabetes

- antioxidant defense

- fasting

- feeding

1. Introduction

The liver is a vital organ for adapting to nutritional changes (e.g., fasting/feeding states) by responding appropriately to achieve metabolic and energy homeostasis through its role in the storage and redistribution of carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and lipids.

2. Liver Metabolic Function and Detoxification

After food intake, the liver stores glucose as glycogen, facilitating glycemic control [1]. Furthermore, the excess carbohydrate in carbohydrate-rich diets is converted into fatty acids via de novo lipogenesis [2][3].

By contrast, the liver produces glucose under fasting conditions, first by glycogenolysis and subsequently through hepatic gluconeogenesis, as the main fuel source for other tissues and contributing to whole-body energy homeostasis [3][4]. The liver’s high metabolic rate means it is also an important source of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

The liver is also the main organ involved in the detoxification of substances harmful to the body. Many drugs, various endogenous molecules, and xenobiotics are lipophilic molecules that need to be metabolized to water-soluble compounds that facilitate their subsequent biliary or renal excretion. Hepatic elimination of most toxic substances involves cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP) [5][6] system and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases [7].

2.1. ROS and Antioxidant Defense

ROS are produced by normal cellular metabolism. The main source of endogenous ROS in the liver, as well as in other organs, is oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondrial electron transfer chain and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate NADPH oxidase enzymes (NOX). Mitochondrial ROS generation will depend on the metabolic rate, although the presence of toxic compounds and their transformation by CYP can sometimes be another source of cytosolic ROS, associated with the consumption of NADPH by CYP [8] ROS is a physiological consequence not only of normal cell function but also of the presence of unpaired electrons in free radicals, which gives them high reactivity and can cause damage to other cellular components, such as proteins, lipids, and DNA. An excess of ROS could therefore trigger a state referred to as oxidative stress.

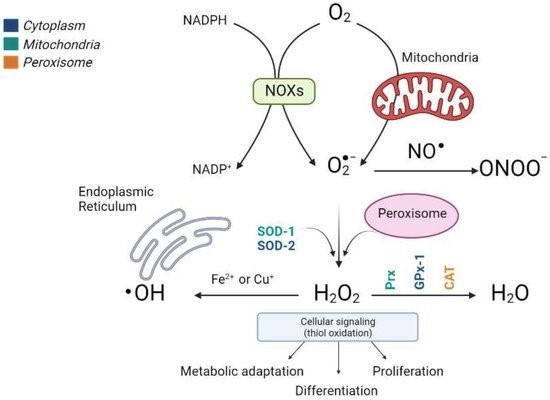

The most important ROS, which includes radical superoxide (O2−), non-radical hydrogenperoxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH−, and the reactive nitrogen species (RNS) that derive from peroxynitrite (ONOO−), are the most relevant radical species present in living systems (Figure 1).

Fortunately, and in contrast, liver cells also have potent antioxidant enzymatic and nonenzymatic mechanisms to prevent ROS and repair any damage caused. The antioxidant enzymes include cytosolic and mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD), which eliminates the superoxide ion by converting it into hydrogen peroxide and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), which are involved in detoxifying hydrogen and cellular peroxides for their conversion into oxygen and water, acting in tandem with peroxiredoxins (Prx), thioredoxins (Trx) and glutaredoxins (Grx), and peroxisomal catalase (CAT) (Figure 1). In addition, nonenzymatic molecules such as reduced glutathione (GSH) are present at high concentrations in the liver; vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, bilirubin, ubiquinone, and uric acid remove ROS and restore reduced protein and lipid reserves. Ceruloplasmin and ferritin also help to eliminate the metals that promote oxidative reactions [9][10][11][12].

Figure 1. Production scheme of different types of ROS and the antioxidant enzymes involved in their elimination. The main sources of endogenous ROS are oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondrial electron transfer chain and NOX enzymes. Cytosolic superoxide (O2−) is quickly converted into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by SOD. H2O2 oxidizes critical thiols within proteins to regulate vital biological processes, including metabolic adaptation, differentiation, and proliferation, or it can be detoxified in water (H2O) by Prx, GPx, and CAT. Moreover, H2O2 reacts with Fe2+ or Cu2+ to generate the hydroxyl radical (•OH) that causes irreversible oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA. The different colors indicate the subcellular location of the antioxidant enzymes. (Image created in biorender.com accessed on 19 October 2021).

Alterations in ROS production and/or diminished defense mechanisms can cause serious problems that trigger liver failure [13][14]

When the balance between ROS production and/or antioxidant mechanisms is modified, the onset of oxidative stress leads to cell damage and toxicity and, therefore, multiple pathologies, including hepatic fibrogenesis [15][16][17].

Prolonged fasting produces oxidative stress, increasing hepatic free radical levels and decreasing antioxidant defenses [18][19]. Nevertheless, intermittent fasting has also been linked to a reduction in oxidative stress [20][21][22][23][24].

2.2. Hepatic Oxidative Stress and Nutritional Status

Oxidative stress may depend on nutritional conditions. Hyperglycemia induces the hyperactivation of NADPH oxidases, increasing oxidative stress [25]. During fasting or calorie restriction, cells are adapted by a metabolic shift in their energy source from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation [26][27][28], which requires an increase in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation for producing adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and therefore involves elevated ROS production [29].

Many chronic liver diseases are known to be associated with elevated oxidative stress [30]. Thus, the hyperglycemic state that characterizes insulin resistance, diabetes, and obesity [31] could modify cellular redox homeostasis and trigger oxidative stress, mirroring the effect of prolonged fasting. Oxidative stress has been involved in the pathophysiology of several liver diseases. For example, free radicals contribute to the onset and progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [32][33], cirrhosis, and liver cancer [34][35]. Mitochondrial ROS promote the presence of other mutations and favor metastatic processes in cancer cells [36].

ROS also operate as signaling molecules in support of normal biological processes and physiological functions. For example, ROS are involved in growth factor signaling, autophagy, hypoxic signaling, immune responses, and stem-cell proliferation and differentiation [37][8][38][39].

3. Nutrient Sensors and Oxidative Stress

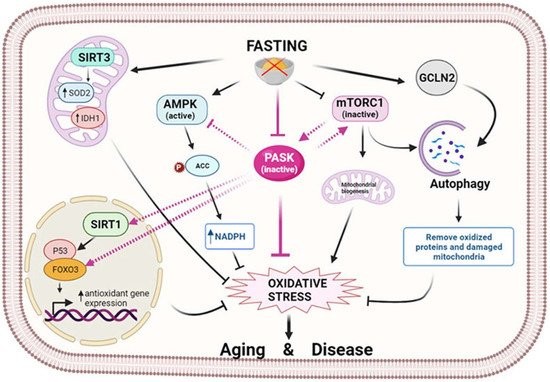

Nutrient sensors detect changes in nutritional status and suitably adapt an intermediary metabolism to maintain energy and oxidative homeostasis. The following are examples of these sensors: AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), PASK, and nicotinamide-dependent histone deacetylases (SIRTs) (Figure 2).

3.1. PASK

PASK/PASKIN is a serine/threonine kinase containing an N-terminal Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain able to respond to several intracellular parameters, as light, oxygen, and redox state [40][41]. These PAS domains have a well-conserved three-dimensional structure that creates a hydrophobic pocket where small metabolites bind, initiating cellular signaling [42][43][44]. In mammals, PASK responds according to nutritional status by contributing to the regulation of glucose homeostasis, energy metabolism and oxidative stress [45][46][47][48]. PASK regulates glucagon and insulin secretion [49][50]. Its role in differentiation processes and epigenetic regulation has recently been described [51][52][53].

PASK-deficient mice record an elevated metabolic rate, which has also been confirmed in PASK knockdown myoblast [54] and neuroblastoma cells [55]. PASK is also a critical signaling regulator of AMPK and mTOR pathways in neuroblastoma N2A cells, the hypothalamus, and the liver [55][56]. Meanwhile, PASK deficiency is associated with a reduction in ROS/RNS levels. Nonetheless, the relationship between PASK and ROS production and oxidative stress is still poorly understood. PAS domains are reported to detect intracellular oxygen, redox state, and various metabolites [41]. Moreover, PASK deficiency is associated with the overexpression of hepatic antioxidant enzymes in basal state and fasting conditions [57] (Figure 2). In addition, PASK deficiency avoids a decrease in the expression of age-related antioxidant enzymes, maintaining ROS/RNS production at a level similar to that of young wild-type (WT) mice. Aged PASK-deficient mice therefore record an overall improvement in their antioxidant mechanism and metabolic phenotype (i.e., PASK deficiency blocks the development of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in aged mice) [58].

Figure 2. Fasting modulates oxidative stress through nutrient sensors. Fasting initiates a signaling cascade that leads to the activation of antioxidant mechanisms to reduce oxidative stress. Several sirtuins, in particular SIRT1 and SIRT3, are activated by fasting and reduce oxidative stress by controlling antioxidant expression at the transcriptional or post-translational level. In turn, fasting activates AMPK, which prevents oxidative stress by decreasing fatty acid synthesis and increasing the level of NADPH. In parallel, mTOR is inhibited, and GCN2 kinase is activated by fasting, thereby facilitating the autophagy process and the elimination of oxidized proteins and damaged mitochondria. At the center of this scenario is PASK, which fasting keeps inactive, exerting an oxidative stress-reducing effect partly by increasing the antioxidant mechanism. This action could be prompted by the inter-regulation of PASK, AMPK, mTOR, and SIRTs through their activation/deactivation, preventing aging and associated diseases. (Image created in biorender.com accessed on 19 October 2021).

4. PASK deficiency reduces hepatic oxidative stress

PASK-deficient mice are protected against obesity and the insulin resistance induced by an HFD [54][59][60]. PASK regulates energy metabolism and glucose homeostasis, especially when adapting to fasting and feeding. Hepatic PASK expression is altered by an HFD [60]. Additionally, PASK deficiency improves the deleterious effects of an HFD such as the overexpression of hepatic genes that occurs in HFD-fed mice. In addition, PASK deficiency restores glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in mice under an HFD, maintaining body weight and serum lipid parameters within the physiological range [60].

High levels of ROS are associated with insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and obesity . The role of PASK in hepatic oxidative stress has been investigated under basal and fasting conditions in order to observe the liver’s adaptive response.

The adaptation to energy requirements under prolonged fasting depends on mitochondrial biogenesis. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α) promotes cellular adjustment to conditions requiring energy input, enhancing mitochondrial mass [61][62][63]. PGC1α and SIRT1 are co-activators of several transcription factors and nuclear receptors, such as nuclear respiratory factors (NRFs), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), and estrogen-related receptors (ERRs).

The expression of coactivator Ppargc1a transcription factors such as Pparg and FoxO3a, and activators such as deacetylase Sirt1, are overexpressed under basal conditions in PASK-deficient mice. Furthermore, the SIRT1 sub-cellular location is mainly nuclear in PASK-deficient mice [57]. Previous data have shown that an increase in nuclear SIRT1 activity, without changes in protein levels, positively correlates with an increased expression of genes regulated by PGC1α [64]. In contrast, the downregulation of PGC1α in obesity has been related to mitochondrial damage and decreased mass [65].

NRF2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) is considered the major regulator of the cellular redox balance[66][67][68]. NRF2 is usually degraded by the proteasome in the absence of oxidative stress. Nevertheless, NRF2 is translocated into the nucleus when there is an increase in such stress, inducing the expression of several genes coding to Glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCLm) and Heme oxygenase (HO1) [69][70]. NRF2 activation could be regulated positively by phosphorylation [71][72]. PASK deficiency, therefore, promotes extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) over-activation [57], and likewise, the PI3K-AKT pathway is over-activated [57]. In turn, PASK deficiency increases the expression of proteins and mRNAs coding to NRF2, GCLm and HO1 under fasting conditions. These results are consistent with the data reporting that AKT activation decreases glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta GSK3β activity and increases NRF2 nuclear translocation [73], which promotes NRF1 expression and activates mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant cellular defenses [74].

Both AMPK activation and elevated SIRT1 under fasting conditions are reported to stimulate FoxO3a nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity [75][76]. Interestingly, PASK deficiency increases the expression of FoxO3a under both basal and fasting conditions, as well as the nuclear location of SIRT1 and AMPK activation [57].

PGC1α induces the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and GPx [77][78][79]. Accordingly, PASK-deficient mice overexpress the hepatic antioxidant enzymes GPx and MnSod in the basal state, and also increase their expression in response to fasting (MnSod, Cu/ZnSod GPx, Gclm and Ho1), while slightly increasing the Cat gene. PASK deficiency is therefore associated with both a reduction in ROS/RNS and slightly higher MnSOD activity under basal conditions [57][58].

All these effects of PASK deficiency are interesting for states that promote an increase in oxidative stress, such as aging, diabetes, and obesity. Here we have described new evidence in this field, whereby PASK blocking is a powerful promotor of antioxidant mechanisms for preventing oxidative stress in the liver.

This entry is adapted from 10.3390/antiox10122028

References

- Peter J. Roach; Anna A. Depaoli-Roach; Thomas D. Hurley; Vincent S. Tagliabracci; Glycogen and its metabolism: some new developments and old themes. Biochemical Journal 2012, 441, 763-787, 10.1042/bj20111416.

- Howard C. Towle; Elizabeth N. Kaytor; Hsiu-Ming Shih; REGULATION OF THE EXPRESSION OF LIPOGENIC ENZYME GENES BY CARBOHYDRATE. Annual Review of Nutrition 1997, 17, 405-433, 10.1146/annurev.nutr.17.1.405.

- Hye-Sook Han; Geon Kang; Jun Seok Kim; Byeong Hoon Choi; Seung-Hoi Koo; Regulation of glucose metabolism from a liver-centric perspective. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2016, 48, e218-e218, 10.1038/emm.2015.122.

- Sally Chiu; Kathleen Mulligan; Jean-Marc Schwarz; Dietary carbohydrates and fatty liver disease. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 2018, 21, 277-282, 10.1097/mco.0000000000000469.

- Robert C. Nordlie; James D. Foster; Alex J. Lange; REGULATION OF GLUCOSE PRODUCTION BY THE LIVER. Annual Review of Nutrition 1999, 19, 379-406, 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.379.

- Richard C Zangar; Mechanisms that regulate production of reactive oxygen species by cytochrome P450. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2004, 199, 316-331, 10.1016/j.taap.2004.01.018.

- Ulrich M. Zanger; Matthias Schwab; Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2013, 138, 103-141, 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007.

- Eugene G. Hrycay; Stelvio M. Bandiera; Involvement of Cytochrome P450 in Reactive Oxygen Species Formation and Cancer. Advances in Pharmacology 2015, 74, 35-84, 10.1016/bs.apha.2015.03.003.

- M. Edeas; D. Attaf; A.-S. Mailfert; M. Nasu; R. Joubet; Maillard Reaction, mitochondria and oxidative stress: Potential role of antioxidants. Pathologie Biologie 2010, 58, 220-225, 10.1016/j.patbio.2009.09.011.

- Michael Schieber; Navdeep S. Chandel; ROS Function in Redox Signaling and Oxidative Stress. Current Biology 2014, 24, R453-R462, 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.034.

- Shingo Oda; Tatsuki Fukami; Tsuyoshi Yokoi; Miki Nakajima; A comprehensive review of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase and esterases for drug development. Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics 2014, 30, 30-51, 10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.12.001.

- Alex Veith; Bhagavatula Moorthy; Role of cytochrome P450s in the generation and metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Current Opinion in Toxicology 2017, 7, 44-51, 10.1016/j.cotox.2017.10.003.

- Liping Zhu; Yankai Lu; Jiwei Zhang; Qinghua Hu; Subcellular Redox Signaling. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 2017, 967, 385-398, 10.1007/978-3-319-63245-2_25.

- H. Jaeschke; A. Ramachandran; Antioxidant Defense Mechanisms. Comprehensive Toxicology 2018, 1, 277-295, 10.1016/b978-0-12-801238-3.64200-9.

- Hartmut Jaeschke; Mary Lynn Bajt; Intracellular Signaling Mechanisms of Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Cell Death. Toxicological Sciences 2005, 89, 31-41, 10.1093/toxsci/kfi336.

- Hartmut Jaeschke; Anup Ramachandran; Reactive oxygen species in the normal and acutely injured liver. Journal of Hepatology 2011, 55, 227-228, 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.006.

- Hartmut Jaeschke; F. Jay Murray; Andrew D. Monnot; David Jacobson-Kram; Samuel M. Cohen; Jerry F. Hardisty; Evren Atillasoy; Anne Hermanowski-Vosatka; Edwin Kuffner; Daniele Wikoff; et al.Grace A. ChappellSuren B. BandaraMilind DeoreSuresh Kumar PitchaiyanGary Eichenbaum Assessment of the biochemical pathways for acetaminophen toxicity: Implications for its carcinogenic hazard potential. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2021, 120, 104859, 10.1016/j.yrtph.2020.104859.

- Ana Blas-Garcia; Juan V. Esplugues; Mitochondria Sentencing About Cellular Life and Death: A Matter of Oxidative Stress. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2011, 17, 4047-4060, 10.2174/138161211798764924.

- V. Sanchez-Valle; Norberto Chavez-Tapia; Misael Uribe; N. Mendez-Sanchez; Role of Oxidative Stress and Molecular Changes in Liver Fibrosis: A Review. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2012, 19, 4850-4860, 10.2174/092986712803341520.

- Matthias Bauer; Anne C. Hamm; Melanie Bonaus; Andrea Jacob; Jens Jaekel; Hubert Schorle; Michael J. Pankratz; Joerg D. Katzenberger; Starvation response in mouse liver shows strong correlation with life-span-prolonging processes. Physiological Genomics 2004, 17, 230-244, 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00203.2003.

- M. Sorensen; Alberto Sanz; Jose Gomez; Reinald Pamplona; M. Portero-Otín; Ricardo Gredilla; Gustavo Barja; Effects of fasting on oxidative stress in rat liver mitochondria. Free Radical Research 2006, 40, 339-347, 10.1080/10715760500250182.

- Gabriele Pizzino; Natasha Irrera; Mariapaola Cucinotta; Giovanni Pallio; Federica Mannino; Vincenzo Arcoraci; Francesco Squadrito; Domenica Altavilla; Alessandra Bitto; Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2017, 2017, 1-13, 10.1155/2017/8416763.

- Michael E. Walsh; Yun Shi; Holly Van Remmen; The effects of dietary restriction on oxidative stress in rodents. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2013, 66, 88-99, 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.05.037.

- Theerut Luangmonkong; Su Suriguga; Henricus A. M. Mutsaers; Geny M. M. Groothuis; Peter Olinga; Miriam Boersema; Targeting Oxidative Stress for the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis. Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology 2018, 175, 71-102, 10.1007/112_2018_10.

- Mary-Catherine Stockman; Dylan Thomas; Jacquelyn Burke; Caroline M. Apovian; Intermittent Fasting: Is the Wait Worth the Weight?. Current Obesity Reports 2018, 7, 172-185, 10.1007/s13679-018-0308-9.

- LeAnne M. Redman; Steven R. Smith; Jeffrey Burton; Corby K. Martin; Dora Il'Yasova; Eric Ravussin; Metabolic Slowing and Reduced Oxidative Damage with Sustained Caloric Restriction Support the Rate of Living and Oxidative Damage Theories of Aging. Cell Metabolism 2018, 27, 805-815.e4, 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.02.019.

- Luke Hatchwell; Dylan J. Harney; Michelle Cielesh; Kieren Young; Yen Chin Koay; John F. O’Sullivan; Mark Larance; Multi-omics Analysis of the Intermittent Fasting Response in Mice Identifies an Unexpected Role for HNF4α. Cell Reports 2020, 30, 3566-3582.e4, 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.051.

- Sandra S. Hammer; Cristiano P. Vieira; Delaney McFarland; Maximilian Sandler; Yan Levitsky; Tim F. Dorweiler; Todd A. Lydic; Bright Asare-Bediako; Yvonne Adu-Agyeiwaah; Micheli S. Sielski; et al.Mariana DupontAna Leda LonghiniSergio Li CalziDibyendu ChakrabortyGail M. SeigelDenis A. ProshlyakovMaria B. GrantJulia V. Busik Fasting and fasting-mimicking treatment activate SIRT1/LXRα and alleviate diabetes-induced systemic and microvascular dysfunction. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 1674-1689, 10.1007/s00125-021-05431-5.

- Liang-Jun Yan; Pathogenesis of Chronic Hyperglycemia: From Reductive Stress to Oxidative Stress. Journal of Diabetes Research 2014, 2014, 1-11, 10.1155/2014/137919.

- Qiuli Liang; Gloria A. Benavides; Athanassios Vassilopoulos; David Gius; Victor Darley-Usmar; Jianhua Zhang; Bioenergetic and autophagic control by Sirt3 in response to nutrient deprivation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Biochemical Journal 2013, 454, 249-257, 10.1042/bj20130414.

- Matthew D. Bruss; Cyrus F. Khambatta; Maxwell A. Ruby; Ishita Aggarwal; Marc K. Hellerstein; Calorie restriction increases fatty acid synthesis and whole body fat oxidation rates. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2010, 298, E108-E116, 10.1152/ajpendo.00524.2009.

- Enzo Nisoli; Cristina Tonello; Annalisa Cardile; Valeria Cozzi; Renata Bracale; Laura Tedesco; Sestina Falcone; Alessandra Valerio; Orazio Cantoni; Emilio Clementi; et al.Salvador MoncadaMichele O. Carruba Calorie Restriction Promotes Mitochondrial Biogenesis by Inducing the Expression of eNOS. Science 2005, 310, 314-317, 10.1126/science.1117728.

- Zhongjian Liu; Yang Sun; Shirui Tan; Liang Liu; Suqiong Hu; Hongyu Huo; Meizhang Li; Qinghua Cui; Min Yu; Nutrient deprivation-related OXPHOS/glycolysis interconversion via HIF-1α/C-MYC pathway in U251 cells. Tumor Biology 2015, 37, 6661-6671, 10.1007/s13277-015-4479-7.

- Ya-Li Li; Hui Xie; Halida Musha; Ying Xing; Cai-Xia Mei; Hai-Jiao Wang; Muhuyati Wulasihan; The Risk Factor Analysis for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Positive Correlation with Serum Uric Acid. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics 2015, 72, 643-647, 10.1007/s12013-014-0346-1.

- Bato Korac; Andjelika Kalezic; Vanja Pekovic-Vaughan; Aleksandra Korac; Aleksandra Jankovic; Redox changes in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes. Redox Biology 2021, 42, 101887, 10.1016/j.redox.2021.101887.

- Antonella Borrelli; Patrizia Bonelli; Franca Maria Tuccillo; Ira D. Goldfine; Joseph L. Evans; Franco Maria Buonaguro; Aldo Mancini; Role of gut microbiota and oxidative stress in the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease to hepatocarcinoma: Current and innovative therapeutic approaches. Redox Biology 2018, 15, 467-479, 10.1016/j.redox.2018.01.009.

- Jagadeesan Nair; Petcharin Srivatanakul; Claudia Haas; Adisorn Jedpiyawongse; Thiravud Khuhaprema; Helmut K. Seitz; Helmut Bartsch; High urinary excretion of lipid peroxidation-derived DNA damage in patients with cancer-prone liver diseases. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2010, 683, 23-28, 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.10.002.

- Ze Chen; Ruifeng Tian; Zhigang She; Jingjing Cai; Hongliang Li; Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2020, 152, 116-141, 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.02.025.

- John D. Hayes; Albena T. Dinkova-Kostova; Kenneth D. Tew; Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 167-197, 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.06.001.

- Andreas Möglich; Rebecca A. Ayers; Keith Moffat; Structure and Signaling Mechanism of Per-ARNT-Sim Domains. Structure 2009, 17, 1282-1294, 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.011.

- Chintan K. Kikani; Stephen A. Antonysamy; Jeffrey B. Bonanno; Rich Romero; Feiyu Fred Zhang; Marijane Russell; Tarun Gheyi; Miyo Iizuka; Spencer Emtage; J Michael Sauder; et al.Benjamin E. TurkStephen K. BurleyJared Rutter Structural Bases of PAS Domain-regulated Kinase (PASK) Activation in the Absence of Activation Loop Phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 41034-41043, 10.1074/jbc.m110.157594.

- Carlos A Amezcua; Shannon M Harper; Jared Rutter; Kevin H Gardner; Structure and Interactions of PAS Kinase N-Terminal PAS Domain: Model for Intramolecular Kinase Regulation. Structure 2002, 10, 1349-1361, 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00857-2.

- Jonathan T. Henry; Sean Crosson; Ligand-Binding PAS Domains in a Genomic, Cellular, and Structural Context. Annual Review of Microbiology 2011, 65, 261-286, 10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151631.

- Philipp Schläfli; Juliane Tröger; Katrin Eckhardt; Emanuela Borter; Patrick Spielmann; Roland H. Wenger; Substrate preference and phosphatidylinositol monophosphate inhibition of the catalytic domain of the Per-Arnt-Sim domain kinase PASKIN. FEBS Journal 2011, 278, 1757-1768, 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08100.x.

- Huai-Xiang Hao; Jared Rutter; The role of PAS kinase in regulating energy metabolism. IUBMB Life 2008, 60, 204-209, 10.1002/iub.32.

- Desiree DeMille; Julianne H. Grose; PAS kinase: A nutrient sensing regulator of glucose homeostasis. IUBMB Life 2013, 65, 921-929, 10.1002/iub.1219.

- Dan-Dan Zhang; Ji-Gang Zhang; Yu-Zhu Wang; Ying Liu; Gao-Lin Liu; Xiao-Yu Li; Per-Arnt-Sim Kinase (PASK): An Emerging Regulator of Mammalian Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7437-7450, 10.3390/nu7095347.

- Verónica Hurtado-Carneiro; Ana Pérez-García; Elvira Alvarez; Carmen Sanz; PAS Kinase: A Nutrient and Energy Sensor “Master Key” in the Response to Fasting/Feeding Conditions. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2020, 11, 1-7, 10.3389/fendo.2020.594053.

- G. Da Silva Xavier; H. Farhan; H. Kim; S. Caxaria; P. Johnson; S. Hughes; M. Bugliani; L. Marselli; P. Marchetti; F. Birzele; et al.G. SunR. ScharfmannJ. RutterK. SiniakowiczG. WeirH. ParkerF. ReimannF. M. GribbleG. A. Rutter Per-arnt-sim (PAS) domain-containing protein kinase is downregulated in human islets in type 2 diabetes and regulates glucagon secretion. Diabetologia 2010, 54, 819-827, 10.1007/s00125-010-2010-7.

- Francesca Semplici; Angeles Mondragon; Benedict MacIntyre; Katja Madeyski-Bengston; Anette Persson-Kry; Sara Barr; Anna Ramne; Anna Marley; James McGinty; Paul French; et al.Helen SoedlingRyohsuke YokosukaJulian GaitanJochen LangStephanie Migrenne-LiErwann PhilippePedro L. HerreraChristophe MagnanGabriela Da Silva XavierGuy A. Rutter Cell type-specific deletion in mice reveals roles for PAS kinase in insulin and glucagon production. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 1938-1947, 10.1007/s00125-016-4025-1.

- Chintan K Kikani; Xiaoying Wu; Litty Paul; Hana Sabic; Zuolian Shen; Arvind Shakya; Alexandra Keefe; Claudio Villanueva; Gabrielle Kardon; Barbara Graves; et al.Dean TantinJared Rutter Pask integrates hormonal signaling with histone modification via Wdr5 phosphorylation to drive myogenesis. eLife 2016, 5, 791, 10.7554/eLife.17985.

- Jimsheena V Karakkat; Suneesh Kaimala; Sreejisha P Sreedharan; Princy Jayaprakash; Ernest A Adeghate; Suraiya A Ansari; Ernesto Guccione; Eric P K Mensah-Brown; Bright Starling Emerald; The metabolic sensor PASK is a histone 3 kinase that also regulates H3K4 methylation by associating with H3K4 MLL2 methyltransferase complex. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, 10086-10103, 10.1093/nar/gkz786.

- Chintan K. Kikani; Xiaoying Wu; Sarah Fogarty; Seong Anthony Woo Kang; Noah Dephoure; Steven P. Gygi; David M. Sabatini; Jared Rutter; Activation of PASK by mTORC1 is required for the onset of the terminal differentiation program. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 10382-10391, 10.1073/pnas.1804013116.

- H.-X. Hao; C. M. Cardon; W. Swiatek; R. C. Cooksey; T. L. Smith; J. Wilde; S. Boudina; E. Dale Abel; Don McClain; J. Rutter; et al. PAS kinase is required for normal cellular energy balance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 15466-15471, 10.1073/pnas.0705407104.

- Verónica Hurtado-Carneiro; Isabel Roncero; Enrique Blazquez; Elvira Alvarez; Carmen Sanz; PAS Kinase as a Nutrient Sensor in Neuroblastoma and Hypothalamic Cells Required for the Normal Expression and Activity of Other Cellular Nutrient and Energy Sensors. Molecular Neurobiology 2013, 48, 904-920, 10.1007/s12035-013-8476-9.

- Verónica Hurtado-Carneiro; Isabel Roncero; Sascha S. Egger; Roland H. Wenger; Enrique Blazquez; Carmen Sanz; Elvira Alvarez; PAS Kinase Is a Nutrient and Energy Sensor in Hypothalamic Areas Required for the Normal Function of AMPK and mTOR/S6K1. Molecular Neurobiology 2014, 50, 314-326, 10.1007/s12035-013-8630-4.

- Pilar Dongil; Ana P´érez García; Verónica Hurtado-Carneiro; Carmen Herrero; E. Blazquez; E. Alvarez; C. Sanz; Pas Kinase Deficiency Triggers Antioxidant Mechanisms in the Liver. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 1-17, 10.1038/s41598-018-32192-w.

- Pilar Dongil; Ana P´érez García; Verónica Hurtado-Carneiro; Carmen Herrero-De-Dios; Elvira Álvarez; Carmen Sanz; PAS kinase deficiency reduces aging effects in mice. Aging 2020, 12, 2275-2301, 10.18632/aging.102745.

- Xiaoying Wu; Donna Romero; Wojciech I. Swiatek; Irene Dorweiler; Chintan Kikani; Hana Sabic; Ben S. Zweifel; John McKearn; Jeremy T. Blitzer; G. Allen Nickols; et al.Jared Rutter PAS Kinase Drives Lipogenesis through SREBP-1 Maturation. Cell Reports 2014, 8, 242-255, 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.006.

- Ana Pérez-García; Pilar Dongil; Verónica Hurtado-Carneiro; Enrique Blázquez; Carmen Sanz; Elvira Álvarez; High-fat diet alters PAS kinase regulation by fasting and feeding in liver. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2018, 57, 14-25, 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.03.003.

- Huiyun Liang; Walter F. Ward; PGC-1α: a key regulator of energy metabolism. Advances in Physiology Education 2006, 30, 145-151, 10.1152/advan.00052.2006.

- S. Soyal; F. Krempler; H. Oberkofler; W. Patsch; PGC-1α: a potent transcriptional cofactor involved in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 1477-1488, 10.1007/s00125-006-0268-6.

- Ching-Feng Cheng; Hui-Chen Ku; Heng Lin; PGC-1α as a Pivotal Factor in Lipid and Metabolic Regulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 3447, 10.3390/ijms19113447.

- Brendon J. Gurd; Yuko Yoshida; Jay T. McFarlan; Graham P. Holloway; Chris D. Moyes; George J. F. Heigenhauser; Lawrence Spriet; Arend Bonen; Nuclear SIRT1 activity, but not protein content, regulates mitochondrial biogenesis in rat and human skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2011, 301, R67-R75, 10.1152/ajpregu.00417.2010.

- Richard M. Reznick; Haihong Zong; Ji Li; Katsutaro Morino; Irene K. Moore; Hannah J. Yu; Zhen-Xiang Liu; Jianying Dong; Kirsty J. Mustard; Simon A. Hawley; et al.Douglas BefroyMarc PypaertGrahame HardieLawrence H. YoungGerald I. Shulman Aging-Associated Reductions in AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Activity and Mitochondrial Biogenesis. Cell Metabolism 2007, 5, 151-156, 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.008.

- Keiko Taguchi; Hozumi Motohashi; Masayuki Yamamoto; Molecular mechanisms of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in stress response and cancer evolution. Genes to Cells 2011, 16, 123-140, 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01473.x.

- Qiang Ma; Role of Nrf2 in Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 2013, 53, 401-426, 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140320.

- Sarah Madden; Laura S. Itzhaki; Structural and mechanistic insights into the Keap1-Nrf2 system as a route to drug discovery. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 2020, 1868, 140405, 10.1016/j.bbapap.2020.140405.

- Makoto Kobayashi; Masayuki Yamamoto; Molecular Mechanisms Activating the Nrf2-Keap1 Pathway of Antioxidant Gene Regulation. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2005, 7, 385-394, 10.1089/ars.2005.7.385.

- Feng He; Xiaoli Ru; Tao Wen; NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 4777, 10.3390/ijms21134777.

- Jianfeng Wang; Li Zhang; Ying Zhang; Meiling Luo; Qiong Wu; Lijun Yu; Haiying Chu; Transcriptional upregulation centra of HO-1 by EGB via the MAPKs/Nrf2 pathway in mouse C2C12 myoblasts. Toxicology in Vitro 2015, 29, 380-388, 10.1016/j.tiv.2014.10.015.

- M. Barančík; L. Grešová; Monika Bartekova; Ima Dovinova; Nrf2 as a Key Player of Redox Regulation in Cardiovascular Diseases. Physiological Research 2016, 1, S1-S10, 10.33549/physiolres.933403.

- P. Rada; A. I. Rojo; S. Chowdhry; M. McMahon; J. D. Hayes; A. Cuadrado; SCF/ -TrCP Promotes Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3-Dependent Degradation of the Nrf2 Transcription Factor in a Keap1-Independent Manner. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2011, 31, 1121-1133, 10.1128/mcb.01204-10.

- Claude A. Piantadosi; Martha Sue Carraway; Abdelwahid Babiker; Hagir B. Suliman; Heme Oxygenase-1 Regulates Cardiac Mitochondrial Biogenesis via Nrf2-Mediated Transcriptional Control of Nuclear Respiratory Factor-1. Circulation Research 2008, 103, 1232-1240, 10.1161/01.res.0000338597.71702.ad.

- Anne Brunet; Lora B. Sweeney; J. Fitzhugh Sturgill; Katrin F. Chua; Paul L. Greer; Yingxi Lin; Hien Tran; Sarah E. Ross; Raul Mostoslavsky; Haim Y. Cohen; et al.Linda S. HuHwei-Ling ChengMark P. JedrychowskiSteven P. GygiDavid A. SinclairFrederick W. AltMichael E. Greenberg Stress-Dependent Regulation of FOXO Transcription Factors by the SIRT1 Deacetylase. Science 2004, 303, 2011-2015, 10.1126/science.1094637.

- Eric Greer; Philip R. Oskoui; Max R. Banko; Jay M. Maniar; Melanie P. Gygi; Steven P. Gygi; Anne Brunet; The Energy Sensor AMP-activated Protein Kinase Directly Regulates the Mammalian FOXO3 Transcription Factor. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, 282, 30107-30119, 10.1074/jbc.m705325200.

- Inmaculada Valle; Alberto Álvarez-Barrientos; Elvira Arza; Santiago Lamas; María Monsalve; PGC-1α regulates the mitochondrial antioxidant defense system in vascular endothelial cells. Cardiovascular Research 2005, 66, 562-573, 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.026.

- María Monsalve; Sara Borniquel; Inmaculada Valle; Santiago Lamas; Mitochondrial dysfunction in human pathologies. Frontiers in Bioscience 2007, 12, 1131-53, 10.2741/2132.

- Julie St-Pierre; Stavit Drori; Marc Uldry; Jessica M. Silvaggi; James Rhee; Sibylle Jager; Christoph Handschin; Kangni Zheng; Jiandie Lin; Wenli Yang; et al.David K. SimonRobert BachooBruce M. Spiegelman Suppression of Reactive Oxygen Species and Neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 Transcriptional Coactivators. Cell 2006, 127, 397-408, 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024.