Nerve axonal injury and associated cellular mechanisms leading to peripheral nerve damage are important topics of research necessary for reducing disability and enhancing quality of life. Model systems that mimic the biological changes that occur during human nerve injury are crucial for the identification of cellular responses, screening of novel therapeutic molecules, and design of neural regeneration strategies. In addition to in vivo and mathematical models, in vitro axonal injury models provide a simple, robust, and reductionist platform to partially understand nerve injury pathogenesis and regeneration. In recent years, there have been several advances related to in vitro techniques that focus on the utilization of custom-fabricated cell culture chambers, microfluidic chamber systems, and injury techniques such as laser ablation and axonal stretching. These developments seem to reflect a gradual and natural progression towards understanding molecular and signaling events at an individual axon and neuronal-soma level. We attempt to categorize and discuss various in vitro models of injury relevant to the peripheral nervous system and highlight their strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities. Such models will help to recreate the post-injury microenvironment and aid in the development of therapeutic strategies that can accelerate nerve repair.

- axon compression

- nerve transection

- nerve injury

- nerve regeneration

- nerve injury model

- in vitro model

1. Transection Injury Models

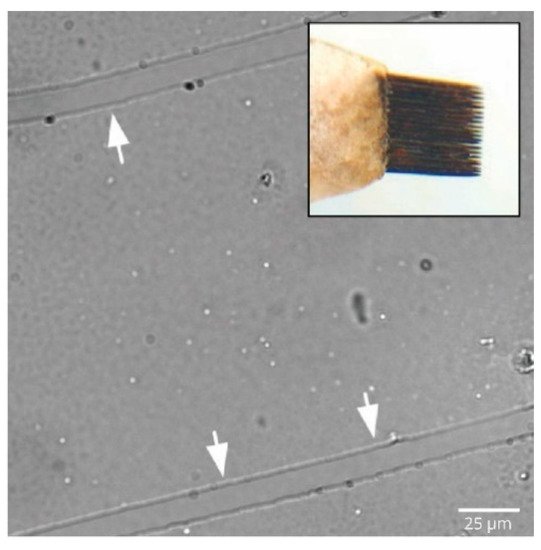

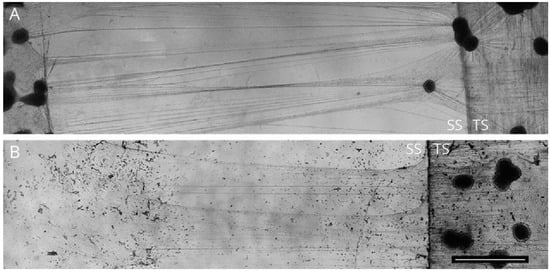

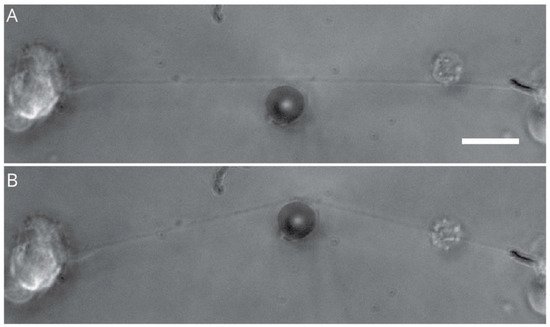

2. Axonal Stretch Injury Model

3. Compression Induced-Injury Models

4. Hydrostatic Pressure Models

Microenvironmental tissue hydrostatic pressure (HP) is an important cellular cue that plays a critical role in regulating cell growth, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis, both in vivo and in vitro [114][28]. In particular, HP is involved in maintaining homeostasis during the development of the optic system, central nervous system, cardiovascular system, cartilage, and bladder tissue. In the CNS, tissue HP is generally between 5 and 15 mmHg [114][28] but differs substantially based on cell and tissue type. However, in the PNS, HP is approximately 3–5 mm Hg in the dorsal root ganglia and approximately 2–3 mm Hg in peripheral nerves [115][29]. The HP gradient in the peripheral nerve is maintained by the interstitial fluid within the endoneurial space (EHP), and any alterations in pressure are known to cause severe pathological effects, secondary to endoneurial ischemia, compression induced injury, and edema. These changes ultimately cause the deformation and collapse of blood vessels, release of osmotic solutes from nerve axons, and build-up of fluid at the proximal site of injury, causing severe damage at the injured nerve [116-118][30]. To mimic in vivo conditions and closely model the mechanical forces affecting the cellular microenvironment, various in vitro HP models have been developed where cells are subjected to HP changes via pressurized chambers, hydrostatic fluid columns, and use of a syringe pump system.5. Metabolic Nerve Injury Models

Metabolic disorders such as diabetes, Gaucher’s disease, and Krabbe disease have been well-known to precipitate progressive neuronal injury and disrupt normal nerve function [125-127][31]. In addition, impaired axonal regeneration is also a common feature that is observed in many metabolic disorders, primarily due to disruption of vascular inputs, inflammatory response, and glia–neuron communication [128][32]. In particular, damage to the peripheral nerve (peripheral neuropathy) is one of the most common complications observed in patients with long-standing diabetes mellitus. Current animal models of hyperglycemia have shed considerable light on the pathogenesis of neural complications in diabetes. Several in vitro studies have contributed strongly to our understanding of the peripheral neuron response to hyperglycemic conditions. Most studies addressing metabolic cellular injuries fundamentally follow a common principle where neuron and/or non-neuronal cells are exposed to in vitro media conditions that closely mimic specific components of the metabolic disorder in question. More commonly, sensory neurons and glial cells derived from murine models, PC-12 cells, and the SHSY5Y cell lines are utilized for in vitro metabolic injury experiments. In this segment, we review techniques utilized to demonstrate metabolic injury in cells exposed to hyperglycemic conditions, since diabetes is a commonly researched topic. Exposure of differentiated PC-12 cells to high concentrations (>9 mg/mL) of glucose has been shown to induce the altered release of dopamine [129][33], enhance reactive oxygen species (ROS), and reduce cell viability and neurite extension [130-132][34]. Similarly, dissociated sensory neurons cultured in glucose concentrations of more than 60 mM showed an increased number of cells that were positive for the injury marker, ATF3 [133][35]. Interestingly, increased ATF3 positive cells were also observed in sensory neurons that were harvested from rats with experimentally induced hyperglycemia [133][35], suggesting a strong co-relation between in vivo and in vitro models. Along the same lines, in vitro models involving neurons cultured from animals with experimentally induced hyperglycemia have consistently demonstrated elevated levels of ROS, reduced neurite outgrowth [134][36], and aberrant calcium ion homeostasis [135][37]. Apart from sensory neurons, sympathetic neurons harvested from superior cervical ganglia (SCG) and celiac/superior mesenteric ganglia (CG/SMG) are some of the other peripheral neural tissues that are commonly utilized for exploring the effect of hyperglycemia in vitro [136][38]. It must also be noted that there have been several studies that have combined metabolic injury models with other PNI models, but the decision remains with the investigator to choose the appropriate combination of models to expand on their specific research questions.6. Chemically Induced Nerve Injury Models

PNI induced by chemical interaction with neural components is commonly seen in patients under anti-cancer treatment [137][39], anti-microbials [137,138][40], and local anesthetics [139-142][41]. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathies (CIPN) are a set of clinical conditions observed in patients administered with chemotherapeutics. CIPN commonly occurs as an undesirable, dose-limiting effect of several chemotherapeutics such as cisplatin, paclitaxel [143,144][42], vinblastine, and vincristine [145][43], mainly due to chemically induced damage to axons and cell bodies of peripheral neurons. Though the underlying mechanism of CIPN is not completely known, axonal degeneration or ‘dying back’ is a well-recognized histopathological hallmark [27,146][44], and understanding the molecular mechanism behind such pathogenesis is crucial to develop therapeutic strategies. In vitro models, especially using dissociated DRG cultures, have been utilized to understand the key cellular features of CIPN. The dose-dependent loss of neurites, fragmentation of neurites, and enlargement of the neuronal cell body have been observed in DRG neurons exposed to bortezomib, cisplatin, eribulin, paclitaxel, and vincristine [147-149][45]. Interestingly, a few studies have also utilized compartmental models to specifically examine the chemically induced dying back effect of axons. Exposure of axons to target chemicals including paclitaxel and vincristine shows clear dysregulation in axonal growth followed by loss of electrical activity [150-152][46]. In addition, in vitro studies in Schwann cell-DRG co-cultures have also shown that anticancer drugs produce a disruption of myelin formation and induce the de-differentiation of Schwann cells to a more immature state, an observation that is consistent with in vivo findings [153][47]. As with chemotherapeutics-related cellular changes in vitro, neuro-toxic mechanisms associated with the activation of common signaling pathways have also been observed with other drugs, including local anesthetics, alcohol, and phenol derivatives. Toxicity-inducing cellular mechanisms include the activation of common signaling pathways linked to intrinsic caspases [154][48], Akt [155][49], and mitogen-activated protein kinase [156][50]. Notably, the exposure of cultured rat DRG neurons to increasing concentrations of lidocaine and bupivacaine has been shown to induce neuronal apoptosis, Schwann cell death [157-159][51], and mitochondrial depletion via caspase and p38MAPK signaling pathways [160,161][52].7. Blast-Induced Injury Models

Explosion-related blast injuries are a major health issue in military medicine, with improvised explosive devices causing many casualties in human conflicts [162][53]. Explosions cause unusual injury patterns that may involve skin, muscle, internal organs, and nerves. Intriguingly, an actual blast-linked injury has been shown to have four distinct mechanisms. The initial intense high-pressure impulse, referred to as a blast wave, is known to induce direct soft-tissue injuries, while the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary injuries relate more to injuries due to flying debris, physical displacement, and other events, respectively [163-165][54]. There have been few in vitro studies that have attempted to mimic the effect of the blast wave on peripheral neurons. One such study exposed DRG cultures enclosed within a rubber glove to the impact of a high-energy missile within a water-filled tube [166][55]. The impact caused high-frequency oscillating pressure waves within the rubber glove that somewhat resembled the blast wave seen during explosions. Interestingly, this study found that within 6 h of impact, almost all DRG neurons demonstrated cytoskeletal disruption, plasma membrane dysfunction, and neurofilament tangles [166][55]. In another blast injury model that was closer to reality, PC-12 cells submerged in water were subjected to the effect of single and multiple primary blasts generated from research department explosives (RDX). Blast-exposed cells showed distinct axonal beading and decreased cell viability with multiple explosion exposure [167][56].8. Challenges and Future Perspectives

While in vitro model systems of nerve injury are promising due to their simplicity in experimental design, there are, however, two broad challenges that need to be addressed going forward: (a) the importance of the coexistence of neuronal and nonneuronal cells in models, and (b) the limitations of 2D culture systems. As firmly established in the past decade, pathogenesis of nerve injury is not limited to neurons or glial cells alone. The surrounding non-neuronal cells are key components in determining the level of injury and regeneration [168-170][57]. Secondary injury or secondary damage results from crosstalk between neighboring cells and neurons, which can be either neuroprotective or destructive. For instance, immune cells play a prominent role after initial nerve injury. Immune cells such as macrophages are known to mediate Wallerian degeneration and hence, a co-culture system that can incorporate immune cells, glia, and neurons may provide more resemblance to an in vivo setting. However, the main challenge remains that it is difficult to maintain long-duration co-cultures of neuronal and non-neuronal cells since proliferative rates of cells are quite different.

Secondly, cultures in a 2D platform have significant shortcomings. For instance, regeneration ability declines with a higher grade-level of injury [100][58]. Grade III and IV that includes damage to endoneurial tubes along with axons, are known to disrupt formation of aligned bands of Bungner, required for regeneration. Replicating grade III and grade IV types of injury is not possible in 2D culture models. The mechanical properties of neurons cultured in 3D extracellular matrix considerably vary from 2D culture, which will invariably affect its response to experimental injury. Though microfluidic devices have made it possible to spatially separate the cell body and axon, somewhat mimicking an in vivo design, the 3D architecture is still lacking.

Organoids provide a platform to culture multi-cell types and develop 3D networks that are physiologically closer to tissues in situ. The field of organoid modelling in the peripheral nervous system is gradually developing, with the incorporation of neuro-immune and neuro-vascular cellular interactions. Though exciting, the field of organoid development for the PNS is still in its infancy, and exciting outcomes can be expected in the future.

References

- Campenot, R.B. Local control of neurite development by nerve growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 4516–4519.

- Campenot, R.B.; Lund, K.; Mok, S.A. Production of compartmented cultures of rat sympathetic neurons. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1869–1887.

- Wall, E.J.; Massie, J.B.; Kwan, M.K.; Rydevik, B.L.; Myers, R.R.; Garfin, S.R. experimental stretch neuropathy: Changes in nerve conduction under tension. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. Vol. 1992, 74, 126–129.

- Loverde, J.R.; Pfister, B.J. Developmental axon stretch stimulates neuron growth while maintaining normal electrical activity, intracellular calcium flux, and somatic morphology. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 308.

- Mahan, M.A.; Yeoh, S.; Monson, K.; Light, A. Rapid stretch injury to peripheral nerves: Biomechanical results. Neurosurgery 2019, 85, E137–E144.

- Yap, Y.C.; King, A.E.; Guijt, R.M.; Jiang, T.; Blizzard, A.; Breadmore, M.C.; Dickson, T.C. Mild and repetitive very mild axonal stretch injury triggers cystoskeletal mislocalization and growth cone collapse. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176997.

- Zhou, M.; Hu, M.; He, S.; Li, B.; Liu, C.; Min, J.; Hong, L. Effects of RSC96 schwann cell-derived exosomes on proliferation, senescence, and apoptosis of dorsal root ganglion cells in vitro. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 7841–7849.

- Ahmed, S.M.; Rzigalinski, B.A.; Willoughby, K.A.; Sitterding, H.A.; Ellis, E.F. Stretch-induced injury alters mitochondrial membrane potential and cellular ATP in cultured astrocytes and neurons. J. Neurochem. 2000, 74, 1951–1960.

- Bianchi, F.; Malboubi, M.; George, J.H.; Jerusalem, A.; Thompson, M.S.; Ye, H. Ion current and action potential alterations in peripheral neurons subject to uniaxial strain. J. Neurosci. Res. 2019, 97, 744–751.

- Tavalin, S.J.; Ellis, E.F.; Satin, L.S. Mechanical perturbation of cultured cortical neurons reveals a stretch-induced delayed depolarization. J. Neurophysiol. 1995, 74, 2767–2773.

- Katanosaka, K.; Takatsu, S.; Mizumura, K.; Naruse, K.; Katanosaka, Y. TRPV2 is required for mechanical nociception and the stretch-evoked response of primary sensory neurons. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16782.

- Loverde, J.R.; Ozoka, V.C.; Aquino, R.; Lin, L.; Pfister, B.J. Live imaging of axon stretch growth in embryonic and adult neurons. J. Neurotrauma 2011, 28, 2389–2403.

- Jocher, G.; Mannschatz, S.H.; Offterdinger, M.; Schweigreiter, R. Microfluidics of small-population neurons allows for a precise quantification of the peripheral axonal growth state. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 166.

- Faktorovich, S.; Filatov, A.; Rizvi, Z. Common compression neuropathies. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 37, 241–252.

- Menorca, R.M.G.; Fussell, T.S.; Elfar, J.C. Peripheral nerve trauma: Mechanisms of injury and recovery. Hand Clin. 2013, 29, 317–330.

- Sugawara, O.; Atsuta, Y.; Iwahara, T.; Muramoto, T.; Watakabe, M.; Takemitsu, Y. The effects of mechanical compression and hypoxia on nerve root and dorsal root ganglia: An analysis of ectopic firing using an in vitro model. Spine 1996, 21, 2089–2094.

- Amir, R.; Kocsis, J.D.; Devor, M. Multiple interacting sites of ectopic spike electrogenesis in primary sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 2576–2585.

- Ma, C.; Greenquist, K.W.; LaMotte, R.H. Inflammatory mediators enhance the excitability of chronically compressed dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 95, 2098–2107.

- Ewan, E.E.; Avraham, O.; Carlin, D.; Gonçalves, T.M.; Zhao, G.; Cavalli, V. Ascending dorsal column sensory neurons respond to spinal cord injury and downregulate genes related to lipid metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 374.

- Martin, S.; Reid, A.; Verkhratsky, A.; Magnaghi, V.; Faroni, A. Gene Expression changes in dorsal root ganglia following peripheral nerve injury: Roles in inflammation, cell death and nociception. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 939–947.

- 1Wang, T.; Hurwitz, O.; Shimada, S.G.; Qu, L.; Fu, K.; Zhang, P.; Ma, C.; LaMotte, R.H. Chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion enhances mechanically evoked pain behavior and the activity of cutaneous nociceptors in mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137512.

- Zhao, J.Y.; Liang, L.; Gu, X.; Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Sun, L.; Atianjoh, F.E.; Feng, J.; Mo, K.; Jia, S.; et al. DNA methyltransferase DNMT3a contributes to neuropathic pain by repressing kcna2 in primary afferent neurons. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14712.

- Myers, K.A.; Rattner, J.B.; Shrive, N.G.; Hart, D.A.; Myers, K.A.; Rattner, J.B.; Shrive, N.G.; Hart, D.A. Hydrostatic pressure sensation in cells: Integration into the tensegrity model. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 85, 543–551.

- Frieboes, L.R.; Gupta, R. An in-vitro traumatic model to evaluate the response of myelinated cultures to sustained hydrostatic compression injury. J. Neurotrauma 2009, 26, 2245–2256.

- Ye, Z.; Wang, Y.; Quan, X.; Li, J.; Hu, X.; Huang, J.; Luo, Z. Effects of mechanical force on cytoskeleton structure and calpain-induced apoptosis in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons in vitro. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52183.

- Liu, S.; Tao, R.; Wang, M.; Tian, J.; Genin, G.M.; Lu, T.J.; Xu, F. Regulation of cell behavior by hydrostatic pressure. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2019, 71, 40803.

- Ask, P.; Levitan, H.; Robinson, P.J.; Rapoport, S.I. Peripheral nerve as an osmometer: Role of endoneurial capillaries in frog sciatic nerve. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1983, 244, C75–C81.

- Lim, T.K.Y.; Shi, X.Q.; Johnson, J.M.; Rone, M.B.; Antel, J.P.; David, S.; Zhang, J. Peripheral nerve injury induces persistent vascular dysfunction and endoneurial hypoxia, contributing to the genesis of neuropathic pain. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 3346–3359.

- Pastores, G.M. Neuropathic gaucher disease. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2010, 160, 605–608.

- Yagihashi, S.; Mizukami, H.; Sugimoto, K. Mechanism of diabetic neuropathy: Where are we now and where to go? J. Diabetes Investig. 2011, 2, 18–32.

- Koshimura, K.; Tanaka, J.; Murakami, Y.; Kato, Y. Effect of high concentration of glucose on dopamine release from pheochromocytoma-12 cells. Metabolism 2003, 52, 922–926.

- Koshimura, K.; Tanaka, J.; Murakami, Y.; Kato, Y. Involvement of nitric oxide in glucose toxicity on differentiated pc12 cells: Prevention of glucose toxicity by tetrahydrobiopterin, a cofactor for nitric oxide synthase. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 43, 31–38.

- Peeraer, E.; van Lutsenborg, A.; Verheyen, A.; de Jongh, R.; Nuydens, R.; Meert, T.F. Pharmacological evaluation of rat dorsal root ganglion neurons as an in vitro model for diabetic neuropathy. J. Pain Res. 2011, 4, 55–65.

- Zherebitskaya, E.; Akude, E.; Smith, D.R.; Fernyhough, P. Development of selective axonopathy in adult sensory neurons isolated from diabetic rats: Role of glucose-induced oxidative stress. Diabetes 2009, 58, 1356–1364.

- Zherebitskaya, E.; Schapansky, J.; Akude, E.; Smith, D.R.; van der Ploeg, R.; Solovyova, N.; Verkhratsky, A.; Fernyhough, P. Sensory neurons derived from diabetic rats have diminished internal Ca2+ stores linked to impaired re-uptake by the endoplasmic reticulum. ASN Neuro. 2012, 4, e00072.

- Sango, K.; Saito, H.; Takano, M.; Tokashiki, A.; Inoue, S.; Horie, H. Cultured adult animal neurons and schwann cells give us new insights into diabetic neuropathy. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2006, 2, 169–183.

- Jones, M.R.; Urits, I.; Wolf, J.; Corrigan, D.; Colburn, L.; Peterson, E.; Williamson, A.; Viswanath, O. Drug-induced peripheral neuropathy: A narrative review. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 15, 38–48.

- Shankarappa, S.A.; Sagie, I.; Tsui, J.H.; Chiang, H.H.; Stefanescu, C.; Zurakowski, D.; Kohane, D.S. Duration and local toxicity of sciatic nerve blockade with coinjected site 1 sodium-channel blockers and quaternary lidocaine derivatives. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2012, 37, 483–489.

- Staff, N.P.; Fehrenbacher, J.C.; Caillaud, M.; Damaj, M.I.; Segal, R.A.; Rieger, S. Pathogenesis of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy: A current review of in vitro and in vivo findings using rodent and human model systems. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 324, 113121.

- Triarico, S.; Romano, A.; Attinà, G.; Capozza, M.A.; Maurizi, P.; Mastrangelo, S.; Ruggiero, A. Vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy (VIPN) in pediatric tumors: Mechanisms, risk factors, strategies of prevention and treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4112.

- Fukuda, Y.; Li, Y.; Segal, R.A. A Mechanistic understanding of axon degeneration in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 481.

- Guo, L.; Hamre, J.; Eldridge, S.; Behrsing, H.P.; Cutuli, F.M.; Mussio, J.; Davis, M. Multiparametric image analysis of rat dorsal root ganglion cultures to evaluate peripheral neuropathy- inducing chemotherapeutics. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 156, 275–288.

- Silva, A.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Ravula, S.K.; Glass, J.D. Evidence for direct axonal toxicity in vincristine neuropathy. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2006, 11, 211–216.

- Imai, S.; Koyanagi, M.; Azimi, Z.; Nakazato, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Ogihara, T.; Yonezawa, A.; Omura, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Wakatsuki, S.; et al. Taxanes and platinum derivatives impair schwann cells via distinct mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5947.

- Werdehausen, R.; Braun, S.; Essmann, F.; Schulze-Osthoff, K.; Walczak, H.; Lipfert, P.; Stevens, M.F. Lidocaine induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway independently of death receptor signaling. Anesthesiology 2007, 107, 136–143.

- El-Boghdadly, K.; Pawa, A.; Chin, K.J. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: Current perspectives. Local Reg. Anesth. 2018, 11, 35.

- Hermanns, H.; Hollmann, M.W.; Stevens, M.F.; Lirk, P.; Brandenburger, T.; Piegeler, T.; Werdehausen, R. Molecular mechanisms of action of systemic lidocaine in acute and chronic pain: A narrative review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, 335–349.

- Kim, E.-J.; Kim, H.Y.; Ahn, J.-H. Neurotoxicity of local anesthetics in dentistry. J. Dent. Anesth. Pain Med. 2020, 20, 55.

- Brull, R.; Hadzic, A.; Reina, M.A.; Barrington, M.J. Pathophysiology and etiology of nerve injury following peripheral nerve blockade. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2015, 40, 479–490.

- Smith, J.E.; Garner, J. Pathophysiology of primary blast injury. J. R. Army Med. Corps 2019, 165, 57–62.

- Antonine Jerusalem, M.D. Continuum modelling of neuronal cell under blast loading. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 3360–3371.

- Suneson, A.; Hansson, H.A.; Lycke, E.; Seeman, T. Pressure wave injuries to rat dorsal root ganglion cells in culture caused by high-energy missiles. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 1989, 29, 10–18.

- Zander, N.E.; Piehler, T.; Boggs, M.E.; Banton, R.; Benjamin, R. In vitro studies of primary explosive blast loading on neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 2015, 93, 1353–1363.