Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Alcido Elenor Wander and Version 2 by Jason Zhu.

Warehouse structure strengthens and provides greater efficiency to rural businesses and producers, inserts and integrates the industry into a competitive market environment, provides economic and social benefits, leads to cost reduction, and increased profit. The economic, social and logistical determinants show the product’s commercialisation, logistical gains, and the producers’ association regarding the development and growth of rural collective action.

- collective action theory of logic

- collective actions

- rural warehouse condominiums

1. Model of Collective Action Rural Warehouse Condominium

The first category aims to present the collective action model of the Rural Warehouse Condominium.

The collective action of the Rural Warehouse Condominium is an association of farmers that share the same objective, storage. In the specific case, the model aims to store grain production in warehouses, shared among all partnering farmers and divided into storage quotas through internal regulations and a set of rules (statute). In addition, the partner farmers own the unit, which comprises the storage units (Metal Silos) and the administrative building, reception and scale, warehouses (hoppers, cleaning machines, dryer, tipper, furnace, etc.), and another small area available. The whole complex is the Rural Warehouse Condominium in approximately 6 hectares.

Initially, the Condominium assumes that farmers alone cannot make the Warehouse financially viable. Additionally, when they come together collectively, the viability of the Warehouse becomes possible since the costs are shared among all partners.

Olson [1][26] reports that the formation of groups begins with a common and primary purpose, in this case, the collective storage structure for the Warehouse Condominiums. In addition, the creation of the Condominium corroborates the economic objectives that can be accomplished with greater strength and effectiveness through collective action.

The model achieves other common goals by collectively making the storage structure viable. Obtaining more significant profit from the sale of the product, minimising costs, adding value to the product, strategic marketing of products, by reducing logistical bottlenecks, rural activity and commercialisation are other incentives for the formation of the collective group Rural Warehouse Condominium, which meet the economic objectives of the Theory of Logic of Collective Action.

It is worth mentioning that the strategic commercialisation of production is one of the main factors in creating the Rural Warehouse Condominium reported by the interviewees. When marketing their products without the Condominium, farmers said having had a reduced profit margin. They were often forced to sell the product right after harvest since they did not have places to store their products. Thus, with an ample supply of the product on the market, usually during harvest periods, the prices of the products end up being lower than in the off-season due to supply and demand.

In addition, the price paid to the producer to deliver the product to third-party warehouses is less than that negotiated at the Condominium. The price received for the product through the Condominium is around 11 to 20% higher. In addition, the sale through the Condominium excludes middlemen. The deal is carried out directly with the buyer or trading company, and the profit increases for the farmer.

In addition, respondents noted the importance of the small number of farmers in each Condominium. Each condominium has around 8 to 24 farmers, with an average of 16 farmers for storage condominium and the productive area around 4500 hectares storage capacity revolving around 450,000 bags of 60 kg (27,000 tons).

As in the case of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, small groups have more satisfactory results due to the ease of control, agility of actions, greater cohesion and greater efficiency, and achieving the collective benefit more quickly. Other aspects such as respect, friendship and characteristics of a social and psychological background are also incentives for collective action and the good functioning of Collective Action [2][37].

In addition, the existence of a small and restricted group is a determining factor for success for the Rural Warehouse Condominiums model. When deciding to set up the Condominium, the farmers had already known each other, had confidence among themselves, and had similar profiles and ideas that contributed to the smooth running of the model’s activities.

In this context, the small group must be well structured and organised, financially stable, and have prior knowledge and/or experiences in collective actions for the model’s success.

Another vital characteristic of Condominiums is the profile of the farmers. Small and medium farms prevail in the Condominiums. It is worth explaining that the profile of farmers in Brazil is different, especially when comparing the South region and the Midwest region, the central grain-producing regions in the country.

The small and medium producers in the South region can vary between 100 to 300 hectares. The large farms are over 1000 hectares. In the Midwest region, small farms have at least 1000 hectares. Thus, the Southern region is characterised by farms with small agricultural areas. This characteristic is for forming a Condominium of Rural Warehouses, as a prominent owner of the Midwest region, in economic terms, can easily make his storage viable. However, in the South, this would not be possible.

This fact is reflected in the incentives for making the model viable. Still, it does not exclude other motivations, such as the social and economic ones that the model provides and will be discussed in the third category.

2. Rural Collective Actions

The second category reveals perceptions and characteristics regarding the different rural Brazilian collective actions.

Among the different Brazilian rural collective actions, the interviewees know the Associations, Cooperatives and Rural Warehouse Condominiums. As for the Cerealists, the interviewees know. However, it is not considered a rural collective action, as only one owner buys and sells grain.

Respondents also reported the prevalence of large Cooperatives in Palotina/Parana and Rural Associations, Brazil. There are fewer rural condominiums, with around six in Palotina/Parana and one in Ipiranga do Sul/Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Associative and cooperative culture is predominant in the country’s Southern Region, which creates and develops collective actions.

As for the diversity of agricultural activities in Rural Condominiums, most interviewees know only about the storage segment. Interviewee A reported some form of a Swine Condominium in Salete, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, but that the Collective Action did not work due to administrative problems, and today it is private. Interviewee B reported knowledge of the Agroenergy Condominium in Marechal Rondon, state of Parana, Brazil (Ajuricaba Condominium) and another Agroenergy Condominium that began recently in the municipality of Entre Rios do Oeste, state of Parana. Both transform pig waste into bioenergy through a biogas plant. In the literature, it is possible to notice recent studies with Condominiums of Agroenergy [3][4][42,43].

Slightly different from bioenergy production from swine manure, interviewee C reported building a Solar Energy Condominium to reduce the electricity costs of the Warehouse Condominium and supply the rural properties themselves.

In contrast, interviewee F commented on the idea of a Silage Condominium sharing Silage machines, which would reduce investment costs and bring greater efficiency to the production process. On the other hand, Interviewee E reported only hearing about a Milk Condominium in Mangueirinha, Parana, Brazil, which delivers the product to the Cooperative.

In the literature, it is possible to notice a diversity of Rural Condominiums. Noteworthy activities include agroenergy [3][4][42,43], logistics (warehouse) [5][6][7][8][9][10][11,22,27,28,31,34], coffee-growing [11][44], dairy [12][13][14][15][16][45,46,47,48,49], and pig farming [14][17][18][47,50,51]. However, studies on the subject are still recent and few.

In addition, among the different rural collective actions, around 80 to 90% of the farmers in the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses participate in other models, such as Credit Cooperatives and Agroindustrial Cooperatives. There are cash loans (financing), purchase of inputs, and sale of products in these relationships.

Researchers noted that rural producers need to associate themselves with collective rural action. Interviewees C and B added: “Now, not associating with anything is bullshit…”, “rural collective actions for agribusiness are critical, there should be more”, respectively. In the Theory of Logic of Collective Action, collective action is more efficient than disorganised individual action. Thus, the rural activity carried out collectively is more efficient to the processes and objectives of everybody.

Fonseca and Machado-da-Silva [19][52] and Garrido and Sehnem [20][4] also corroborate the importance of Collective Actions in competitive and fierce business environments to face competitive scenarios and the survival of institutions strategically.

For Saes [21][25], collective action achieves each person's interests. The objectives are more easily achieved, and the associates’ profit is maximised, goods or services are provided, the “rules of the game” are changed, and conflicts are resolved.

Thus, the interviewees’ unanimously asserted the importance of collective rural actions for agribusiness and the whole production chain. Researchers can highlight the security, aggregation of value to the product, generation of jobs, dilution of costs, a gain of scale, quality of food, marketing increase in profit and use of technologies as main advantages.

Interviewee E commented on the importance of farmers staying together because rural collective actions cannot be achieved without union. Likewise, interviewee G said that soon he sees the formation of an Association between Condominiums of Rural Warehouses to ensure greater representativeness of the category and seek better financing conditions, such as lower interest rates, as different needs may arise.

In addition, for the rural producers of the Condominiums, the viability of the storage structure and the extra profit obtained from direct sales and strategic marketing were only possible thanks to the cooperative union of producers. “I was always very accountable and was not viable alone. I was going to have a high maintenance cost to play alone, and in this collective way, I think it went well” (interviewee B); “…what changes are for the groups that make it up, who manage to have a slightly higher final gain in his currency, which is the grain” (interviewee A).

The “surplus” with the sale of the products (grains) directly to the market, without intermediaries in the transaction, and the possibility to sell the product at any time of the year, especially in the off-season when the price of the product is best, are the main benefits. This condition is possible considering the Condominium’s capacity of storage.

In addition, the rural collective action models differ from each other. The Condominiums of Rural Warehouses differ from the other collective actions because it is driven to a smaller, non-business group, with a limited warehouse share, and less bureaucratic.

In addition, the difference between the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses and other Brazilian Rural Collective Actions is that the farmer owns his grains since the warehouse is his, and he can choose the best time to sell his product and product quality. Complementarily, the condominiums of rural warehouses participants have greater decision-making power in meetings. Concerning their product, they also have the autonomy to decide when it will be sold and to whom, that is, they can negotiate better prices for it, as opposed to selling at over-the-counter prices offered in other rural collective actions without negotiation.

Decisions and management in smaller collective action models are also faster and more agile, as in Warehouse Condominiums. There are tax advantages over other models, as they are not companies; condominiums do not receive discounts.

Concerning the problems of agro-industrial logistics, such as deficits in warehouses and queues for loading and unloading, the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses avoid these problems. Considering that there are few partners in the Condominium, the flow of loading and unloading in the silos does not generate queues. In addition, each partner has their share of storage, so each producer knows the space available to store their products in the Condominium silos. Suppose space is lacking, depending on the crop years or increases in production. Farmers can use the quota of another partner. When the managers/owners of the Condominium decide it is possible to expand the storage capacity, they can construct new silos.

3. Economic and Social Incentives for Rural Warehouse Condominiums

The third category discusses the role of Economic Incentives and Social Incentives in front of Rural Warehouse Condominiums, motivating bases for forming groups according to the Theory of Logic of Collective Action.

First, respondents almost unanimously agreed about Economic Incentives relating interest rates to warehouse financing. When asked about the role of Economic Incentives in forming groups, researchers discussed two relations: Governmental economic incentives and market-based economic incentives.

The governmental economic incentive applies because the Government restricts contributions with financial incentives to the collective action model of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses. Mainly to incentive programs for the construction or expansion of Warehouses with competitive interest rates for small and medium rural producers.

Currently, the central government program available for Warehouses is the PCA—Program for the Construction and Expansion of Warehouses—with interest rates ranging from 6% to 7% per year, 6% for investments with a grain storage capacity of up to 6000 tons and 7% above that [22][53]. According to the interviewees, interest rates for farmers are high. They have risen over the last decade, mainly for small and medium farms, being a disincentive for structuring new Warehouse Condominiums and new construction of storage units in the country.

It is worth remembering that there is a storage deficit in the country and obsolete storage units that need modernisation. At a more favourable time, the lack of warehouse spaces still implies not enjoying storage benefits, such as product conservation and commercialisation.

In addition, researchers asked the interviewees about the non-knowledge about the model of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses by the Government. So, researchers perceive a need for greater articulation between governmental economic and social agents to learn about the country’s reality and outline economic and social incentives for this emerging Brazilian rural collective action model. This articulation is essential given the model’s contribution to reducing the warehouse deficit, greater product competitiveness, regional growth and development for agribusiness and municipalities, and money turnover in the country’s economy.

In addition, on the economic incentives of a market order, the extra profit that rural producers have when marketing production with the Rural Warehouse Condominium is exemplified: “The main differential, economic incentive, would be the spread, which the Condominium gains with selling the grains owned by farmers” (Interviewee G).

This characteristic shows the extra gain with the owner’s product when selling his production through the Condominium, without an intermediary in operation. Even stored, the producers keep the property of the produce (grains) because the participants own the silos. This gain can vary between 11 to 20% more per grain bag, depending on the time of year.

It was also verified that Government economic incentives are unattractive and insufficient for the country’s construction and development of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses. However, concerning market economic incentives, mainly about the extra gain with the product in strategic marketing, there are favourable scenarios for Rural Collective Action, solid determinants for the rural model.

In the Theory of Logic of Collective Action, economic incentives are paramount for forming groups. If there are no economic incentives, a group does not survive long term, and there is no reason for the activity to remain in the market. Thus, producers’ additional gain in marketing the product through the Condominium is a condition for the organisation to survive and promote its members’ interests. However, high-interest rates for the financing of condominium warehouses have hindered the rural model.

Maeda and Saes [23][36] consider that Economic Incentives are superior to Social Incentives. Thus, the economic gain from the rural activity is a fundamental condition for the group to survive in the market.

Economic Incentives are not the only determinants for forming groups under the Theory of Logic of Collective Action. There are also Social Incentives, such as prestige, respect, friendship and social and psychological characteristics that encourage people to organise themselves into groups. These characteristics are evident in the collective actions of the Rural Warehouse Condominiums.

The interviewees highlighted social incentives, including greater interpersonal relationships; exchange of knowledge information; technical and professional growth; job creation; learning among the Condominium’s professionals and farmers, etc. Note the diversity of social incentives generated with the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, which strengthen the rural movement and benefit from the interaction between all model members.

The Logic of Collective Action describes the “social pressure” in-group behaviour with Social Incentives. There is a set of rules in Condominiums of Rural Warehouses Condominiums, the model’s Statute. The farmers’ efforts and the model follow the Statute. In addition, each producer and/or employee is willing to help and collaborate with whatever is needed in the Condominium of which he is part. The demands are not binding, but rather, because the rural producers own this model and know each other, everyone collaborates in meeting the needs that may arise.

In addition, at Condominium meetings, everyone freely expresses their ideas, respects themselves and actively participates in the model. Interviewee A also reports that the rules and responsibilities are more “easily enforceable” in the smaller group, the Condominium.

For Olson, “social pressure” makes it easier to fulfil individual obligations in smaller groups due to the appreciation of the company of friends and colleagues and the zeal for social status, social prestige and self-esteem. The author reports that the social incentives and “social pressure” only work in small groups so that each member has “face to face contact with all others” [2][37]. In this sense, Social Incentives favour Condominiums in smaller groups.

4. Small Groups and Large Groups

The fourth category analyses the characteristics of rural collective actions between small and large groups. According to the Collective Action Logic Theory, smaller groups have more advantages over larger groups, smaller groups are more efficient and effective, and social incentives work better in small groups.

It is possible to notice characteristics that distinguish small and large groups and stand out in small groups. Small groups are treated in this study as groups of up to 25 people (production around 4500 hectares, that is, 315,000 bags of 60 kg, with 70 bags yield per hectare on average). Large groups would already have 100 and 200 members (around 2.5 million bags of 60 kg).

This distinction is considerable for the development of Rural Warehouse Condominiums since this condition implies the efficiency of the progress of all Collective Action activities, including the financial return to maintain the model itself. According to interviewee A, a Condominium of Rural Warehouses can be small or large. Since it is tiny and has low production, it would be unfeasible to pay for the entire structure of the Condominium, which includes expenses such as energy, employees, maintenance, etc. On the other hand, a large producer could have its storage structure on his farm. In this way, he would make the installation costs viable individually. It is worth remembering that the Condominium model brings other advantages, not only the feasibility of own storage.

The small group still presents the advantage of the social characteristic for all members, a strong point described in all statements and meets the Theory of Logic of Collective Action regarding Social Incentives. Smaller groups achieve collective benefit more easily than larger groups; Social Incentives work best in small groups. Since the smaller the group, this fact occurs, the easier it is to reach the optimum point of getting the collective benefit. That is why larger organisations form small groups, smaller subdivisions [1][26].

According to the testimonies, a group with fewer people has fewer different opinions. Thus, it is easier to reach a consensus, and more occasional disagreements will arise.

In addition, small group participants start from the same common goal more simply. This aspect is more satisfactory in smaller groups. Smaller groups are more easily controlled, people know each other better, organisation and communication are easier, and the small group is more united and of greater affinity.

Other advantages prevail in small groups, such as in Warehouse Condominiums. The main benefits of the model are as follows: greater agility in decisions, speed in unloading and absence of queues at the silo, higher profit margin (product quality and direct sales), better prices and conditions in the purchase of inputs, express their opinions in the group for being smaller, logistical proximity to storage with ownership, and being the “owner of your product” provide freedom in marketing.

Individual action is also better recognised in smaller groups. In the Theory of Logic of Collective Action, this occurs since, in large groups, the typical participant knows that their efforts will not influence the result too much. He will be affected in the same way by the final decisions. Thus, individual effort in larger groups will not influence the decision. In smaller groups, the personal effort reflects more on the final decision.

Another fact identified in the collective rural models was the market competition between small and large groups. Even before the existence of Rural Condominiums in the region, large groups prevailed, which held 100% of the sales and associates. With smaller groups in the area that are similarly competitive or more, there is more competition among the different associative forms. This fact is positive for the end customer since, in more competitive markets, groups must always seek their best quality products and strive to be a more efficient and effective organisation. Otherwise, the client or associate will look elsewhere for these qualities.

Furthermore, for small groups, access to rural credit and bargaining power may be more challenging to achieve. Financing requires guarantees from rural producers. Therefore, they must come together to fulfil this criterion needed to finance the storage structure—high-interest rates aside for small producers. Together, to gain more bargaining power and scale, smaller producers must come to achieve these goals. In larger groups, such aspects are more easily achieved.

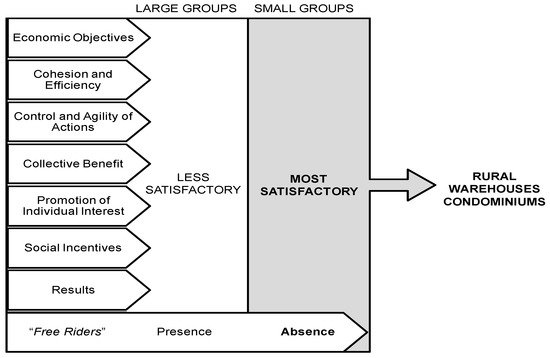

Finally, it is possible to highlight the main differences between small and large groups according to the Rural Collective Action of Rural Warehouses Condominiums and the Theory of Logic of Collective Action (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Differences between Small Groups and Large Groups.

Based on the results, researchers verified that in small groups, such as the ones forming Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, the economic and social objectives, the control and agility of actions, the promotion of individual interests, cohesion and efficiency, and the results are more satisfactory than in large groups. Additionally, it is noteworthy that there are no free-riders in small groups since everyone participates actively, knows each other and are driven by friendly relationships alongside Social Incentives, which are more easily attainable in smaller Collective Actions.

Finally, for a small group to be successful compared to larger groups, it must be well structured, organised, and financially supported. In the case of Condominiums of Rural Warehouse, the rural partner producers already belonged and/or knew models of collective actions, such as Cooperatives and other types of Associations. In this way, they already had practical and prior knowledge about collective effort to make the collective action Condominium of Rural Warehouse model works correctly.

5. Determining Factors of Rural Warehouse Condominiums

The fifth category qualitatively discusses the main determining factors for Condominiums of Rural Warehouses.

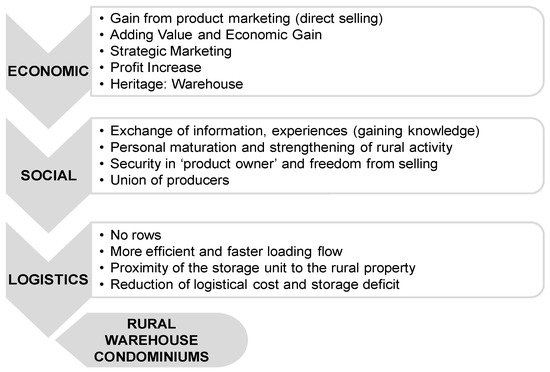

Some factors repeated the testimonies of charges and went against Economic Incentives and social conditions for forming groups. The advantages of product commercialisation, direct sales and superior profitability—the added value, the logistical gains, no queues, less flow and proximity of the storage unit to the rural property—and the social gains from the model of collective action are decisive benefits for Rural Warehouse Condominiums. Figure 3 presents the significant economic, social and logistics determinants for forming the condominiums of rural warehouses.

Figure 3. Determinants of Rural Warehouse Condominiums.

In the economic determinant group, one of the main motivating characteristics for structuring rural collective action is illustrated: economic gain with such activity. This characteristic is remarkable for forming groups according to the Logic of Collective Action. Having its warehouse structure, understood as an extension of rural property, allows the rural producer to sell his products directly, without intermediaries in commercialisation, and at a reasonable time for him, causing an increase in his profit and adding value to the product through the collective model and the best quality of the grain. It is worth remembering that the warehouse also belongs to the rural producer, which means that it is his property. This characteristic differentiates the Condominiums from other Brazilian Rural Collective Actions. Additionally, it guarantees the power of negotiation of the producers and dilution of costs between all partners.

Researchers obtained these characteristics through the following main motivating economic factors highlighted by the interviewees: “security of having your product in your warehouse”, “adding value”, “storing and selling the product”, “economic gain”, “increased profitability” and “product commercialisation”.

As social determinants for the structuring and development of Rural Warehouse Condominiums, the main factor is the importance of unity among producers. This characteristic is a condition for the creation and development of Condominiums. All producers act as partners, have good relationships and share the same ideas. Common goals are essential for the business to be entirely successful.

Along with these social aspects, the rural producers belonging to the Condominium gain from exchanging information and experiences, thereby generating knowledge. Through such activities, producers still enjoy personal maturity and strengthen rural activity, leading to advantages in local growth and development. Again, Olson [1][26] describes that social incentives are more easily achieved and work better in small groups, as with Condominiums.

Finally, as to the logistical determinants, the Rural Warehouse Condominiums circumvented some logistical bottlenecks faced by rural producers, such as queues at third-party storage units, mainly in peak seasons. Thus, the model provides better efficiency in the loading and unloading flow and reduces the storage and logistics deficit.

6. Perspectives of Rural Warehouse Condominiums

The sixth and final category comprised the rural collective action model Rural Warehouse Condominium in Brazil.

The knowledge of the Condominiums of Rural Warehouses is restricted to the South of the country, mainly in the region of Palotina in the state of Parana, Brazil. Even the Condominium managers are unaware of other Warehouse Condominiums in other cities or areas of the country, including the Ipiranga Condominium and the Condominiums in the Palotina region, which are not known.

However, there are favourable scenarios for implementing new Rural Warehouse Condominiums, mainly for small and medium producers and places where there are logistical bottlenecks and storage deficits. This would be useful for rural producers who aim to enjoy the advantages of the condominium model, such as storage itself.

The interviewees provide some critical characteristics for the success of collective action of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses and for them to develop in other regions, such as (i) profile of the rural producer, producers who are unable to make their storage structure viable, or who seek be in some Rural Collective Action; (ii) regions with an associative culture and/or places where cooperatives or rural collective actions already exist; (iii) the group must have confidence and an entrepreneurial spirit; (iv) all farmers will be responsible for the smooth running of the model; (v) have a neutral, reliable figure with knowledge in agribusiness and marketing to manage and sell the products of the farmers (Condominium manager); and (vi) ascertain the production and storage needs of each partner before setting up the Condominium.

In turn, the Condominiums of Rural Warehouse model is more sought after by people from the regions of origin of the Condominiums. Still, there are also interested parties from other areas of the country. The target audience is usually made up of farmers who have heard of the model and are looking to visit the existing Condominiums of Rural Warehouses to understand how it works and assess its viability.

Interviewee C reported interest and visits from different persons to learn about the model, from farmers, people from other states, and companies that sell silos. Interviewee D also reported the disclosure of Condominiums by companies that sell silos and said having been visited by students from the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), Parana, Brazil, so that they could learn about electrical specificities as students of Electrical Engineering and agricultural colleges in the region, acting as temporary interns.

Complementarily, there was an expansion of this rural collective action in other municipalities in the South region. The interviewees are aware of new Condominiums of Rural Warehouses under construction. Some of them are in the vicinity of Marechal Cândido Rondon (Parana, Brazil) and Não-Me-Toque (Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil), and in the municipalities of Nova Santa Rosa (Parana, Brazil), Terra Roxa (Parana, Brazil) and Sapezal (Mato Grosso, Brazil). However, other states have already sought information, such as Minas Gerais and Mato Grosso do Sul. The interviewees cannot say whether Warehouse Condominiums have been established in these locations.

Furthermore, regarding the long-term success of the model, it is crucial to define the set of condominium rules (by laws) the issue of leaving members or family succession/death of a partner. It was noted that the topic could generate conflict between partners if it is not managed in a transparent and equal way among all. Thus, it is vital to set clear rules regarding whether the Condominium allows the sale of the storage quota, its valuation and who has the privilege of buying, for example, if another partner can purchase the quota or if an external member of society can.

Finally, Government economic incentives become motivators for the creation and development of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, mainly via financing programs for storage, which is in line with the profile of the rural producer and compatible interest rates. Together, the profile of the rural producer is consistent with the model since smaller rural producers who are unable to access a storage structure are eligible to become part of the Rural Warehouse Condominium model and can enjoy the other advantages that the collective action brings.

As a dimension of the rural model Condominiums of Rural Warehouses, researchers suggest that collective action should meet the productivity needs and static storage capacity of partner producers, should have the capability to expand and should be financially viable for all members.

Considering the perspectives of the managers/owners of Condominiums of Rural Warehouses and some findings of this study, researchers identified the owners’ demands and perspectives with other types of Rural Condominiums. Some examples include the Energy Condominiums to reduce energy costs from a sustainability perspective; the Silage Condominiums share machines and generate greater efficiency and reduce costs. Both models do not yet exist. Only Agroenergy Condominiums transform animal waste into bioenergy; thus, researchers suggest technical and financial feasibility studies on the topics.