Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most common malignancy of the pancreas, accounts for 3% of all cancers and 7% of cancer-related deaths and is expected to claim 48,220 lives in 2021 in the US (American Cancer Society). Despite continued scientific efforts, the 5-year survival rate of all surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) stages combined remains a dismal 10% (American Cancer Society). Surgery remains the only curative option for PDAC patients.

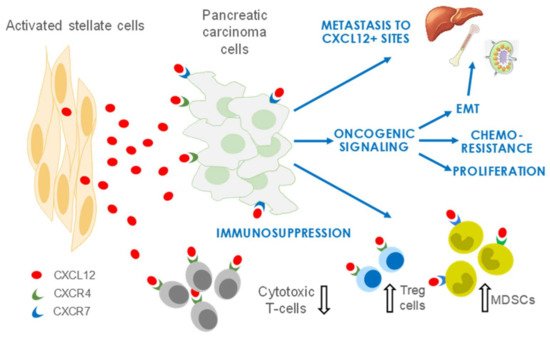

CXCL12, a member of the CXC family of chemokines, is secreted by the activated fibroblasts (for which we use the terms aPSCs and CAFs interchangeably in this review) of the TME and is a crucial mediator reported to contribute to growth and metastasis in PDAC and several other solid tumors, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and breast, ovarian, and colorectal carcinomas. CXCL12 has a pervasive influence in PDAC by increasing proliferation, enhancing invasion and metastasis, and promoting chemoresistance and immune evasion of tumor cells.

- pancreatic cancer

- cxcl12

- tumor microevironment

1. Introduction

2. CXCL12 Signaling in PDAC

2.1. CXCL12 Promotes PDAC Survival and Proliferation Signaling

2.2. CXCL12 Signaling Promotes Immune Evasion

2.3. CXCL12 Signaling Promotes Angiogenesis

2.4. CXCL12 Signaling Promotes Chemoresistance

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Rosenberg, P.S.; Jemal, A. Emerging cancer trends among young adults in the USA: Analysis of a population-based cancer registry. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e137–e147.

- Sleightholm, R.L.; Neilsen, B.K.; Li, J.; Steele, M.M.; Singh, R.K.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; Oupicky, D. Emerging roles of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in pancreatic cancer progression and therapy. Pharm. Ther. 2017, 179, 158–170.

- Neesse, A.; Michl, P.; Frese, K.K.; Feig, C.; Cook, N.; Jacobetz, M.A.; Lolkema, M.P.; Buchholz, M.; Olive, K.P.; Gress, T.M.; et al. Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer. Gut 2011, 60, 861–868.

- Murakami, T.; Hiroshima, Y.; Matsuyama, R.; Homma, Y.; Hoffman, R.M.; Endo, I. Role of the tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2019, 3, 130–137.

- Schnittert, J.; Bansal, R.; Prakash, J. Targeting Pancreatic Stellate Cells in Cancer. Trends Cancer 2019, 5, 128–142.

- Fu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zeng, S.; Shen, H. The critical roles of activated stellate cells-mediated paracrine signaling, metabolism and onco-immunology in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 62.

- Hosein, A.N.; Brekken, R.A.; Maitra, A. Pancreatic cancer stroma: An update on therapeutic targeting strategies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 487–505.

- Huang, H.; Brekken, R.A. Recent advances in understanding cancer-associated fibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2020, 319, C233–C243.

- Balkwill, F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 540–550.

- Sun, X.; Cheng, G.; Hao, M.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Taichman, R.S.; Pienta, K.J.; Wang, J. CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 chemokine axis and cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010, 29, 709–722.

- Puchert, M.; Engele, J. The peculiarities of the SDF-1/CXCL12 system: In some cells, CXCR4 and CXCR7 sing solos, in others, they sing duets. Cell Tissue Res. 2014, 355, 239–253.

- Chatterjee, S.; Azad, B.B.; Nimmagadda, S. The intricate role of CXCR4 in cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2014, 124, 31–82.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Marchesi, F.; Monti, P.; Leone, B.E.; Zerbi, A.; Vecchi, A.; Piemonti, L.; Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P. Increased survival, proliferation, and migration in metastatic human pancreatic tumor cells expressing functional CXCR4. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 8420–8427.

- Bachem, M.G.; Schunemann, M.; Ramadani, M.; Siech, M.; Beger, H.; Buck, A.; Zhou, S.; Schmid-Kotsas, A.; Adler, G. Pancreatic carcinoma cells induce fibrosis by stimulating proliferation and matrix synthesis of stellate cells. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 907–921.

- Hwang, R.F.; Moore, T.; Arumugam, T.; Ramachandran, V.; Amos, K.D.; Rivera, A.; Ji, B.; Evans, D.B.; Logsdon, C.D. Cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts promote pancreatic tumor progression. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 918–926.

- Wang, Z.; Ma, Q.; Liu, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhao, L.; Shen, S.; Yao, J. Blockade of SDF-1/CXCR4 signalling inhibits pancreatic cancer progression in vitro via inactivation of canonical Wnt pathway. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 99, 1695–1703.

- Shen, B.; Zheng, M.Q.; Lu, J.W.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, T.H.; Huang, X.E. CXCL12-CXCR4 promotes proliferation and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 5403–5408.

- Lee, E.; Han, J.; Kim, K.; Choi, H.; Cho, E.G.; Lee, T.R. CXCR7 mediates SDF1-induced melanocyte migration. Pigment. Cell Melanoma. Res. 2013, 26, 58–66.

- Li, X.; Ma, Q.; Xu, Q.; Liu, H.; Lei, J.; Duan, W.; Bhat, K.; Wang, F.; Wu, E.; Wang, Z. SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling induces pancreatic cancer cell invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in vitro through non-canonical activation of Hedgehog pathway. Cancer Lett. 2012, 322, 169–176.

- Billadeau, D.D.; Chatterjee, S.; Bramati, P.; Sreekumar, R.; Shah, V.; Hedin, K.; Urrutia, R. Characterization of the CXCR4 signaling in pancreatic cancer cells. Int. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2006, 37, 110–119.

- Singh, A.P.; Arora, S.; Bhardwaj, A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Kadakia, M.P.; Wang, B.; Grizzle, W.E.; Owen, L.B.; Singh, S. CXCL12/CXCR4 protein signaling axis induces sonic hedgehog expression in pancreatic cancer cells via extracellular regulated kinase- and Akt kinase-mediated activation of nuclear factor kappaB: Implications for bidirectional tumor-stromal interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 39115–39124.

- Weekes, C.D.; Song, D.; Arcaroli, J.; Wilson, L.A.; Rubio-Viqueira, B.; Cusatis, G.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Messersmith, W.A.; Winn, R.A.; Hidalgo, M. Stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha mediates resistance to mTOR-directed therapy in pancreatic cancer. Neoplasia 2012, 14, 690–701.

- Yan, Z.; Ohuchida, K.; Fei, S.; Zheng, B.; Guan, W.; Feng, H.; Kibe, S.; Ando, Y.; Koikawa, K.; Abe, T.; et al. Inhibition of ERK1/2 in cancer-associated pancreatic stellate cells suppresses cancer-stromal interaction and metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 221.

- Zhou, W.; Guo, S.; Liu, M.; Burow, M.E.; Wang, G. Targeting CXCL12/CXCR4 Axis in Tumor Immunotherapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 3026–3041.

- Ma, J.; Su, H.; Yu, B.; Guo, T.; Gong, Z.; Qi, J.; Zhao, X.; Du, J. CXCL12 gene silencing down-regulates metastatic potential via blockage of MAPK/PI3K/AP-1 signaling pathway in colon cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 20, 1035–1045.

- Samara, G.J.; Lawrence, D.M.; Chiarelli, C.J.; Valentino, M.D.; Lyubsky, S.; Zucker, S.; Vaday, G.G. CXCR4-mediated adhesion and MMP-9 secretion in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2004, 214, 231–241.

- Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Z.; Fan, L.; Shen, X.; Zhou, S.; Chen, D. Stem cell autocrine CXCL12/CXCR4 stimulates invasion and metastasis of esophageal cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36149–36160.

- Kaufman, H.L.; Atkins, M.B.; Subedi, P.; Wu, J.; Chambers, J.; Joseph Mattingly, T., II; Campbell, J.D.; Allen, J.; Ferris, A.E.; Schilsky, R.L.; et al. The promise of Immuno-oncology: Implications for defining the value of cancer treatment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 129.

- Hilmi, M.; Bartholin, L.; Neuzillet, C. Immune therapies in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Where are we now? World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 2137–2151.

- Clark, C.E.; Hingorani, S.R.; Mick, R.; Combs, C.; Tuveson, D.A.; Vonderheide, R.H. Dynamics of the immune reaction to pancreatic cancer from inception to invasion. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 9518–9527.

- Bayne, L.J.; Beatty, G.L.; Jhala, N.; Clark, C.E.; Rhim, A.D.; Stanger, B.Z.; Vonderheide, R.H. Tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 822–835.

- Winograd, R.; Byrne, K.T.; Evans, R.A.; Odorizzi, P.M.; Meyer, A.R.; Bajor, D.L.; Clendenin, C.; Stanger, B.Z.; Furth, E.E.; Wherry, E.J.; et al. Induction of T-cell Immunity Overcomes Complete Resistance to PD-1 and CTLA-4 Blockade and Improves Survival in Pancreatic Carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 399–411.

- Seo, Y.D.; Jiang, X.; Sullivan, K.M.; Jalikis, F.G.; Smythe, K.S.; Abbasi, A.; Vignali, M.; Park, J.O.; Daniel, S.K.; Pollack, S.M.; et al. Mobilization of CD8(+) T Cells via CXCR4 Blockade Facilitates PD-1 Checkpoint Therapy in Human Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3934–3945.

- Fukunaga, A.; Miyamoto, M.; Cho, Y.; Murakami, S.; Kawarada, Y.; Oshikiri, T.; Kato, K.; Kurokawa, T.; Suzuoki, M.; Nakakubo, Y.; et al. CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes together with CD4+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and dendritic cells improve the prognosis of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 2004, 28, e26–e31.

- Ino, Y.; Yamazaki-Itoh, R.; Shimada, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Kosuge, T.; Kanai, Y.; Hiraoka, N. Immune cell infiltration as an indicator of the immune microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 914–923.

- Watt, J.; Kocher, H.M. The desmoplastic stroma of pancreatic cancer is a barrier to immune cell infiltration. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e26788.

- Protti, M.P.; De Monte, L. Immune infiltrates as predictive markers of survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 210.

- Balachandran, V.P.; Łuksza, M.; Zhao, J.N.; Makarov, V.; Moral, J.A.; Remark, R.; Herbst, B.; Askan, G.; Bhanot, U.; Senbabaoglu, Y.; et al. Identification of unique neoantigen qualities in long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2017, 551, 512–516.

- Vonderheide, R.H. The Immune Revolution: A Case for Priming, Not Checkpoint. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 563–569.

- Feig, C.; Jones, J.O.; Kraman, M.; Wells, R.J.; Deonarine, A.; Chan, D.S.; Connell, C.M.; Roberts, E.W.; Zhao, Q.; Caballero, O.L.; et al. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20212–20217.

- Kraman, M.; Bambrough, P.J.; Arnold, J.N.; Roberts, E.W.; Magiera, L.; Jones, J.O.; Gopinathan, A.; Tuveson, D.A.; Fearon, D.T. Suppression of antitumor immunity by stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-alpha. Science 2010, 330, 827–830.

- Wang, Z.; Yan, R.; Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Moresco, P.; Yao, M.; Hechtman, J.F.; Weiss, M.J.; Janowitz, T.; Fearon, D.T. Pancreatic cancer cells assemble a CXCL12-keratin 19 coating to resist immunotherapy. bioRXiv 2020.

- Matsuo, Y.; Ochi, N.; Sawai, H.; Yasuda, A.; Takahashi, H.; Funahashi, H.; Takeyama, H.; Tong, Z.; Guha, S. CXCL8/IL-8 and CXCL12/SDF-1alpha co-operatively promote invasiveness and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 124, 853–861.

- Guleng, B.; Tateishi, K.; Ohta, M.; Kanai, F.; Jazag, A.; Ijichi, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Washida, M.; Morikane, K.; Fukushima, Y.; et al. Blockade of the stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 axis attenuates in vivo tumor growth by inhibiting angiogenesis in a vascular endothelial growth factor-independent manner. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 5864–5871.

- Singh, S.; Srivastava, S.K.; Bhardwaj, A.; Owen, L.B.; Singh, A.P. CXCL12-CXCR4 signalling axis confers gemcitabine resistance to pancreatic cancer cells: A novel target for therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 103, 1671–1679.

- Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Guan, J.; Wang, L.; Ren, X.; Shi, X.; Liang, Z.; Liu, T. Paracrine SDF-1α signaling mediates the effects of PSCs on GEM chemoresistance through an IL-6 autocrine loop in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 3085–3097.

- Arora, S.; Bhardwaj, A.; Singh, S.; Srivastava, S.K.; McClellan, S.; Nirodi, C.S.; Piazza, G.A.; Grizzle, W.E.; Owen, L.B.; Singh, A.P. An undesired effect of chemotherapy: Gemcitabine promotes pancreatic cancer cell invasiveness through reactive oxygen species-dependent, nuclear factor kappaB- and hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha-mediated up-regulation of CXCR4. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 21197–21207.

- Morimoto, M.; Matsuo, Y.; Koide, S.; Tsuboi, K.; Shamoto, T.; Sato, T.; Saito, K.; Takahashi, H.; Takeyama, H. Enhancement of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis due to acquisition of gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer: Effect of CXCR4 antagonists. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 305.

- Khan, M.A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Zubair, H.; Patel, G.K.; Arora, S.; Khushman, M.; Carter, J.E.; Gorman, G.S.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.P. Co-targeting of CXCR4 and hedgehog pathways disrupts tumor-stromal crosstalk and improves chemotherapeutic efficacy in pancreatic cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 8413–8424.

- Bhardwaj, A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Singh, S.; Arora, S.; Tyagi, N.; Andrews, J.; McClellan, S.; Carter, J.E.; Singh, A.P. CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling counteracts docetaxel-induced microtubule stabilization via p21-activated kinase 4-dependent activation of LIM domain kinase 1. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 11490–11500.

- Domanska, U.M.; Timmer-Bosscha, H.; Nagengast, W.B.; Oude Munnink, T.H.; Kruizinga, R.C.; Ananias, H.J.; Kliphuis, N.M.; Huls, G.; De Vries, E.G.; de Jong, I.J.; et al. CXCR4 inhibition with AMD3100 sensitizes prostate cancer to docetaxel chemotherapy. Neoplasia 2012, 14, 709–718.