Conciliating nature conservation and tourism development is an increasingly important task for authorities in charge of managing protected areas and requires an adequate knowledge of visitors′ preferences and recreational behavior. In this light, the researchers used data collected by means of a choice experiment to investigate recreational preferences at Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park, a protected area located in Northeastern Italy. More specifically, we analyzed the determinants of visitors’ decisions to engage with different activities in the park. This is important information for park managers, as different recreational activities have both different impact on the natural heritage and different capability to generate revenue for nature conservation and for enhancing the quality of life of local communities.

1. Introduction

Protected areas provide a wide range of environmental, recreational and economic benefits to visitors and local communities. While the conservation of natural heritage and the preservation of ecosystem services are the primary aims of protected areas, the sustainable development of tourism and recreation is increasingly important

[1]. Tourism in protected areas allows the generation of revenues for nature conservation, and can also contribute to the development of local communities

[2,3][2][3]. The increasing demand for recreation opportunities and the need to conciliate such activities with nature conservation puts pressure on park authorities to develop effective sustainable management plans that can provide benefits to both natural heritage and tourism. The sustainability of tourism and recreation requires management actions that generate sufficient revenues to cover the costs of nature and biodiversity preservation while minimizing the negative impacts of tourism on such preservation

[4]. As suggested by the literature

[5[5][6],

6], the design of management actions should be based on a systematic valuation of tourists’ attitudes, preferences and behavior. Several studies

[7,8][7][8] emphasize the need to understand tourists’ preferences for recreation in protected areas to develop management plans capable of balancing the dual goals of conservation and tourism development. Knowledge and understanding of tourists’ preferences and expectations can lead to better tourism planning, as it can provide detailed insights into recreational demand and how to sustainably develop tourism

[9].

The choice experiment (CE) approach has been extensively used worldwide to investigate tourists’ preferences and recreational behavior. Examples of CE studies that focused on outdoor recreation in protected areas include

[10] at Oulanka National Park in Finland,

[11] at Kruger National Park in South Africa,

[12] at National Park Hoge Kempen in Belgium,

[3] at national and natural parks in Romania,

[13] at Peñuelas Lake National Reserve in Chile,

[14] at the Black-Faced Spoonbill Reserve and

[15] at Shei-Pa National Park, both in Taiwan,

[16] at Dachigam National Parkland in India, and

[17] at birding and avitourism sites in Australia and the United Kingdom. The existing literature using CE to analyze tourism in protected areas has focused on several aspects of recreational demand, such as preferences for improvements to recreational features

[18], ecotourism development

[19], and willingness to financially support nature conservation

[14] and land management under alternative uses

[20]. While such studies provide a comprehensive picture of the drivers of preferences towards protected areas and their features, there is less information available in the literature about the determinants of decisions by tourists to practice specific activities. Among such studies,

[21] carried out a CE study in Scotland to analyze how the choice to practice rock climbing is affected by the features of climbing sites. In

[22], the focus was on fishing, specifically by analyzing how fishing sites characteristics affect anglers’ choices in the Southeastern US. In

[23], the focus was on hunting and snowmobiling in a national park in Maine (US), accounting for the effect of both site features and visitors’ past experience with such activities. In

[24], the question of how hiking choices are affected by the number of people met in trails was explored in a CE addressing visitors to Garibaldi Park in British Columbia.

A common trait of the above studies is that they focus on only one or few activities rather than simultaneously accounting for the plurality of activities than can practiced in parks. This is a relevant limitation of the existing literature, as the recognition of the portfolio of available activities is an important information for the sustainable management of protected areas, as different activities can have different impacts on natural heritage and different capabilities to generate revenue for its conservation and for the development of local communities. In addition, the possibility of complementarity among activity needs should be viewed as an enhancer to the demand for recreation, as subsets of activities may support one another in maintaining demand over time.

Given this background, the aim of our study is to analyze the drivers of the decision to engage with a plurality of recreational activities in protected areas. Specifically, our research questions relate to how the choice of activity is affected by: (i) recreational site features; (ii) visitors’ characteristics, with specific focus on previous park experience and socio-demographic descriptors. Towards this purpose, and following the above literature

[10,24][10][24], we used data collected by means of a choice experiment aimed at investigating recreational preferences at Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park, a national park located in Northeastern Italy. Respondents were presented with scenarios, including different recreational sites chosen from among those most visited in the park and different levels of improvement of the current recreational features, and were asked to choose which activities they would engage in at each site. The choice experiment (CE) survey also collected information about several individual characteristics related to recreational habits and previous experience with recreational activities. The analysis of such data enabled a detailed characterization of the determinants of activity choice, which in turn allowed us to produce suggestions on how to increase the flow of different visitor types (e.g., mountain bikers or hikers), which is crucial information for the development of sustainable tourism.

2. Determinants of Activities Choice

Table 1 reports the aggregate choice frequencies for the nine activities, along with the number of choice scenarios in which they were available. Hiking, picnicking and sightseeing were available in all scenarios, as they can be practiced during the entire year and do not require any specific park feature. These were all activities with high choice frequency, especially hiking, which was chosen in 61% of the scenarios; next were picnicking (51.6%) and sightseeing (44.8%). Rock climbing, on the other hand, has the lowest choice frequency among activities that can be practiced the whole year (13%), which is likely related to the higher requirements in terms of skill and physical effort that this activity calls for. The same seems to apply to winter activities, with snowshoeing being much more popular among people that visit parks in the winter (47.1%) compared to alpine skiing (15.6%) and ice climbing (4.8%).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of activities choice.

| Activity |

Number of Scenarios in which Available |

Chosen when Available (%) |

| Hiking |

10,026 |

61.02 |

| Rock climbing |

8910 |

13.00 |

| Picnic |

10,026 |

51.57 |

| Horse riding |

9288 |

20.59 |

| Mountain biking |

9288 |

27.89 |

| Sightseeing |

10,026 |

44.80 |

| Snowshoeing |

738 |

47.05 |

| Alpine skiing |

722 |

15.58 |

| Ice climbing |

474 |

4.80 |

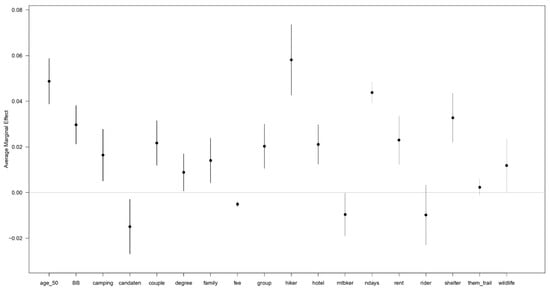

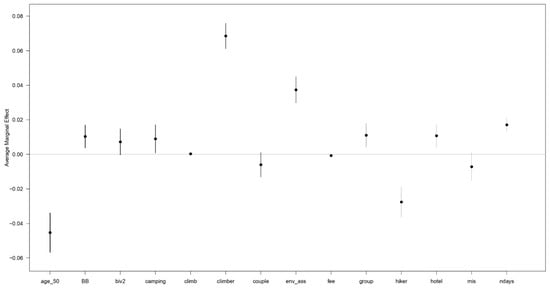

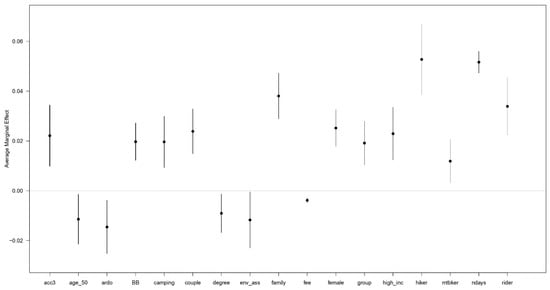

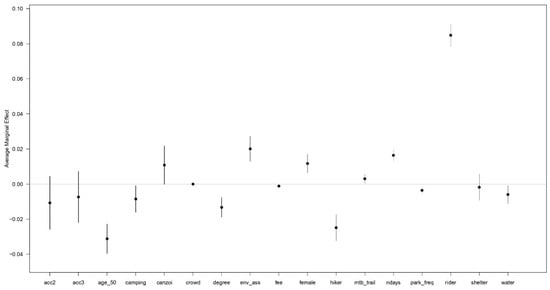

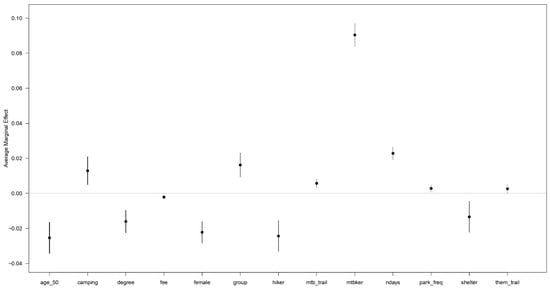

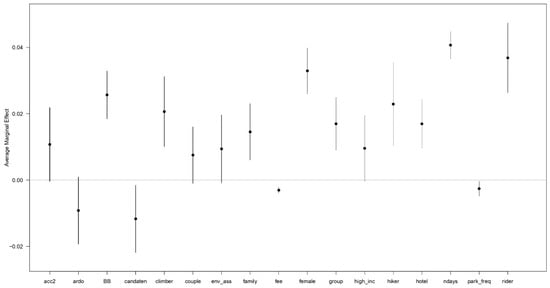

Table 2 reports the results for the six binary logit models, while

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate the statistically significant average marginal effects. Notably, two variables have a consistent effect across all activities: entrance fee and duration of visit. The first is always associated with a negative sign, thereby implying—consistent with classical economic theory—that the higher the cost of visiting the park, the lower the probability that individuals choose to practice any given activity in its territory. It is also interesting to note how the smallest marginal effects were retrieved for climbing and horse riding, the two most “specialized” activities. Duration of visit, on the other hand, has a positive coefficient for all activities, suggesting that all activities are more likely to be practiced by visitors who spend several days at the park.

Figure 1. Marginal effects for hiking probability.

Figure 2. Marginal effects for rock climbing probability.

Figure 3. Marginal effects for picnic probability.

Figure 4. Marginal effects for horse riding probability.

Figure 5. Marginal effects for mountain biking probability.

Figure 6. Marginal effects for sightseeing probability.

Table 2. Binary logit model estimates.

| |

Hiking |

Rock Climbing |

Picnic |

Horse Riding |

Mountain Biking |

Sightseeing |

| Intercept |

−2.361 *** |

−3.673 *** |

−2.806 *** |

−3.142 *** |

−2.81 *** |

−2.764 *** |

| Sites (baseline: Passo Croce d’Aune) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Val di Lamen |

−0.042 |

0.030 |

−0.113 |

0.018 |

−0.069 |

−0.067 |

| Val Canzoi |

−0.011 |

- |

0.039 |

0.250 * |

−0.145 |

0.034 |

| Val del Mis |

0.015 |

−0.238 |

0.007 |

0.363 |

−0.072 |

−0.008 |

| Val Cordevole |

−0.076 |

−0.082 |

−0.028 |

0.278 |

0.023 |

−0.018 |

| Candaten |

−0.167 ** |

- |

−0.201 |

- |

- |

−0.233 ** |

| Val dell′Ardo |

−0.159 ** |

0.056 |

−0.204 *** |

0.131 |

−0.113 |

−0.167 ** |

| Sites features |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Main sites closed on Sunday |

0.057 |

0.160 |

0.049 * |

−0.184 |

0.062 |

0.102 * |

| Main sites closed on weekends |

0.097 |

0.010 |

0.102 |

−0.140 |

−0.031 |

0.045 |

| Entrance fee |

−0.028 *** |

−0.017 * |

−0.025 *** |

−0.018 ** |

−0.025 *** |

−0.022 *** |

| Bivouacs open upon request (baseline: not available) |

0.008 |

0.121 |

0.032 |

0.126 |

0.036 |

0.069 |

| Bivouacs always open (baseline: not available) |

0.026 |

−0.021 |

−0.018 |

−0.034 |

0.046 |

0.004 |

| Bivouacs w/ food & firewood (baseline: not available) |

0.001 |

0.029 |

0.023 |

0.105 |

0.036 |

−0.002 |

| Crowding |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

−0.002 * |

0.001 |

0.001 |

| Picnic areas |

−0.010 |

−0.001 |

−0.011 |

−0.007 |

0.030 |

−0.017 |

| Wildlife spots |

0.001 * |

−0.088 |

0.006 |

0.002 |

−0.111 |

−0.038 |

| Via ferratas: cable part of path (base: not available) |

0.009 |

0.169 |

0.116 |

−0.111 |

−0.070 |

0.097 |

| Via ferratas: cable whole path (base: not available) |

−0.027 |

0.118 |

0.101 |

−0.057 |

−0.094 |

0.058 |

| Via ferratas: cable & holds (base: not available) |

−0.036 |

0.085 |

0.058 |

0.024 |

−0.091 |

0.005 |

| Climbing routes |

0.001 |

0.006 * |

0.001 |

0.002 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

| MTB trails |

0.007 |

0.063 * |

0.013 |

0.087 ** |

0.037 * |

−0.007 |

| Thematic trails |

0.013 *** |

0.032 |

0.002 |

0.009 |

0.032 * |

0.010 |

| Water spots |

−0.001 |

−0.005 |

−0.01 |

0.092 * |

0.005 |

0.007 |

| Individual characteristics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Past visits at PNDB |

−0.008 |

−0.011 |

−0.006 |

−0.072 *** |

0.021 * |

−0.018 * |

| Hotel (baseline: second home) |

0.118 *** |

0.154 * |

0.028 |

−0.037 |

0.020 |

0.126 *** |

| Bed&Breakfast (baseline: second home) |

0.170 *** |

0.152 * |

0.152 *** |

0.129 |

0.111 |

0.195 *** |

| Rented flat (baseline: second home) |

0.137 *** |

−0.082 |

0.070 |

−0.113 |

−0.015 |

−0.042 |

| Camping (baseline: second home) |

0.098 ** |

0.123 |

0.138 *** |

−0.185 ** |

0.141 ** |

0.050 |

| Shelter (baseline: second home) |

0.195 *** |

−0.039 |

0.112 |

−0.079 ** |

−0.190 *** |

−0.031 |

| Visit with family (baseline: visit alone) |

0.080 ** |

−0.046 |

0.242 *** |

−0.063 |

−0.046 |

0.106 ** |

| Visit in group (baseline: visit alone) |

0.123 *** |

0.177 * |

0.103 *** |

−0.003 |

0.165 *** |

0.121 *** |

| Visit in couple (baseline: visit alone) |

0.128 *** |

−0.106 |

0.137 *** |

−0.021 |

−0.049 |

0.059 * |

| Hiker |

0.346 *** |

−0.394 *** |

0.334 *** |

−0.389 *** |

−0.273 *** |

0.188 *** |

| Rock climber |

−0.021 |

1.222 *** |

0.009 |

0.405 |

0.308 |

0.148 *** |

| Mountain biker |

−0.050 * |

0.311 |

0.074 * |

0.124 |

1.057 *** |

0.029 |

| Horse rider |

−0.064 * |

0.244 |

0.218 *** |

1.326 *** |

0.219 |

0.272 *** |

| Degree |

0.043 * |

−0.070 |

−0.066 * |

−0.205 *** |

−0.226 *** |

0.009 |

| Female |

0.031 |

0.028 |

0.168 *** |

0.195 *** |

−0.276 *** |

0.254 *** |

| Environmental association |

0.049 |

0.655 *** |

−0.086 * |

0.287 *** |

0.042 |

0.072 * |

| Age above 50 years old |

0.283 *** |

−0.812 *** |

−0.075 * |

−0.478 *** |

−0.288 *** |

−0.026 |

| High income |

0.091 |

−0.020 |

0.145 *** |

−0.140 |

−0.009 |

0.070* |

| Number of visit days |

0.259 *** |

0.321 *** |

0.341 *** |

0.272 *** |

0.287 *** |

0.310 *** |

| Observations |

45,117 |

22,792 |

45,117 |

35,878 |

35,853 |

45,117 |

| Log-likelihood |

−23,514.26 |

−48,24.81 |

−21,473.58 |

−10,487.96 |

−10,627.17 |

−19,368.74 |

Here, we review each model in detail in the order presented above. For hiking, two of the site-specific constants have a statistically significant effect, those for Candaten and Val dell′Ardo. In both cases the sign is negative, which suggests that Passo Croce d′Aune (the baseline site) is more attractive for hiking compared to the other two sites. This was an expected result, as Candaten is a site focused on providing facilities for picnics and Val dell’Ardo is a less popular site than Passo Croce d′Aune based on the information on visitors flows provided by the park authority. As for site features, as the number of thematic trails and wildlife sites grows, this affects the probability of choosing to practice this activity. In both cases the effect is positive, suggesting that those two features increase hiking probability. More specifically, the probability of practicing this activity increases by around 0.2% for each additional thematic trail and by around 1% for each additional wildlife site (

Figure 1). The effects of individual characteristics see all accommodations (compared to the baseline second home) associated with a statistically significant and positive coefficient. Among these, the highest marginal effect is found for shelter: individuals staying in such facilities have a 3% higher probability of practicing hiking compared to those staying in their second home. This can be explained by the fact that shelters are situated at high altitude and are usually reached by hiking. Thus, people visiting parks with others have a higher probability of choosing to practice hiking compared to those who visit parks alone. The marginal effects are similar for the three variables (family, group and couple), with couples having a slightly higher effect (around 2%). As expected, people who usually hike in parks are more likely to choose this activity than other people. This variable has the highest marginal effect among all those included in the model, with hikers being 6% more likely to choose this activity compared to individuals who usually do not practice it. Those who usually practice mountain biking are less likely to choose hiking. Finally, older individuals (more than 50 years old) are more likely to choose to practice hiking (marginal effect around 5%), and the same holds for graduates (marginal effect around 1%). The other sociodemographic variables do not seem to affect hiking probability.

The probability of practicing rock climbing, on the other hand, does not seem to be affected by sites. Among site features, it can be noticed that, as expected, the number of climbing routes has a significant and positive effect, although the marginal effect is rather small. The other feature significantly affecting rock climbing probability is the number of mountain biking trails, with a positive effect. This activity seems to be more likely to be practiced in group compared to the other options (alone, with family and with a partner). More specifically, being in a group increases the rock climbing probability by around 1.5%. As expected, those who already practiced rock climbing in the past are more likely to choose this activity. As in the previous model, this variable is associated with the highest marginal effect: experienced climbers are 7% more likely to choose this activity. Being a hiker, by contrast, decreases the rock climbing probability (marginal effect around 2.5%). Age also seems to have a substantial effect, with younger individuals being more likely to choose rock climbing (marginal effect around 4.5%) than older ones. A slightly smaller effect was retrieved for those who belong to environmental associations, which are 4% more likely to practice this activity.

Picnic probability, similarly to hiking, is negatively affected by Val dell′Ardo, which is a site mainly dedicated to high altitude hikes and has limited picnic facilities. Concerning site features, it is notable that the number of picnic areas has a non-significant effect. This may suggest that the current provisioning of picnic areas is considered adequate by visitors and increasing them would not increase the probability of choosing to practice this activity. The only site feature with a significant effect is the closure to vehicular access of the main sites on Sunday, with a positive effect. Specifically, it seems that introducing this park management action would increase the picnicking probability by around 2%. A possible interpretation for this result is that people interested in this activity may prefer not to be disturbed by traffic while practicing it. It should also be considered that Sunday is the day on which picnicking is most commonly practiced in the park. Moving to the role of individual characteristics, staying in camping or a bed and breakfast has a positive effect, with similar marginal effects (around 2%). Visiting the park alone is associated with the lowest picnicking probability among the four group types, which is an expected result considering that this is usually a social activity. Family has the highest marginal effect among the four options (around 4%), followed by couple and group. A significant and positive effect was found for hikers, rock climbers and horse riders. As such, it seems that picnicking attracts people practicing various types of activities and can be seen as an example of complementarity between different activities. All of the socio-demographic variables influence probability of practicing this activity. Those more likely to choose it are non-graduated individuals, older people, woman and those with high income. Belonging to an environmental association, however, has a negative effect.

Horse riding probability is positively affected by Val di Canzoi, one of the two most popular sites in the park (the other being Val del Mis). The park feature most directly related to this activity, water spots, has a significant and positive effect, as expected. Specifically, the availability of water spots increases the probability of practicing horse riding by 1%. Similarly to picnicking, closing access to vehicles increases the probability of practicing this activity. In this case, however, both levels (closing on Sunday and closing both Sunday and Saturday) have a significant effect (marginal effect around 1% in both cases). It seems reasonable that horse riders prefer to avoid traffic during their activity. A low number of people encountered during the visit also seems to positively affect this activity, as suggested by the significant and negative sign for crowding. Finally, mountain biking trails have a positive effect as well. Again, the interpretation may be similar to that for the two previous features, in that dedicated mountain biking routes would decrease the number of mountain bikers met during horse riding activity. Moving to individual characteristics, it is interesting to notice how—differently from the previous activities—the number of past visits at the park has a significant effect. Specifically, it seems that a low number of previous visits increases the probability of practicing horse riding, i.e., new visitors may be more attracted by this activity than experienced ones. As concerns the impact of accommodations, staying in camping or shelter has a significant and negative effect. For shelter, the negative relation is easily explainable considering that horse riding is typically practiced in the valleys and not at high altitude, where such facilities are located. Another difference compared to the previous models is that this activity is not influenced by whom respondents usually visit parks with. Consistent with the previous activities, experienced horse riders are more likely to choose this activity than those who never practiced it. The marginal effect (around 8%) is the largest among all variables, similar to the other cases. Finally, all socio-demographics affect the probability of choosing this activity, with the exception of income. Specifically, it seems to be preferred by young, women and non-graduated visitors. Belonging to an environmental association has a positive effect as well.

Turning our attention to mountain biking, its choice probability is not affected by any site. Among site features, once again the activity-specific feature (i.e., mountain biking trails) has a significant and positive effect. Specifically, one additional mountain park trail increases choice probability by 0.5%. The other feature with significant (and positive) effect is the number of thematic trails. The number of past visits has a significant and positive effect, which suggests that those who frequently visited the park in the past are more likely to choose this activity. Staying in a shelter has a negative effect. As with horse riding, this is consistent with mountain biking being typically practiced in the valleys. Those who usually visit parks in groups are around 2% more likely to choose this activity compared to those visiting on their own. Having experience with mountain biking has a substantial positive effect (a marginal effect around 9%), consistent with the results of the previous models. Finally, concerning socio-demographics, being a man, non-graduated and younger makes choosing this activity more likely, with a marginal effect ranging from 2% to 3%.

Finally, sightseeing is less likely to be chosen when the site is Candaten and Val dell′Ardo (compared to Passo Croce d′Aune). The interpretation may be the same as illustrated for hiking, for which the same result was found. Having the main sites closed to vehicular access on Sundays has a significant and positive effect (1% increase in choice probability). None of the other features has a significant effect, which may be due to sightseeing being a generic activity which is not specifically related to any feature. On the other hand, most individual characteristics affect the probability of choosing this activity. Park frequency has a negative effect, i.e., people who rarely (or never) visited the park in the past are more likely to be willing to engage with sightseeing. It is reasonable that people with limited experience with the park would be more interested in acquiring knowledge about the territory. This result is in line with that related to accommodation, for which we found that people staying in a hotel or bed and breakfast (who are usually tourists) are more likely to engage in sightseeing than people having a second home in the park. The marginal effects are around 3% for bed and breakfast and 2% for hotel. This activity is more likely to be practiced by individuals who visit parks with other people, compared to those who visit on their own. The highest marginal effect was estimated for groups, at around 1.5%. As for the other of the two most generic activities (picnicking), having previous experience with hiking, climbing and horse riding has a significant and positive effect, which is consistent with sightseeing being practiced alongside other activities. As concerns socio-demographics, sightseeing is more likely to be engaged in by women and wealthier individuals.