Retinal neurodegeneration is predominantly reported as the apoptosis or impaired function of the photoreceptors. Retinal degeneration is a major causative factor of irreversible vision loss leading to blindness. Degenerative retinal diseases are reported as heterogeneous and multiple etiological groups of disorders that hamper the vision of human beings, resulting in compromised quality of life. Retinitis pigmentosa (RP), age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), Stargardt macular dystrophy (STGD), and Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) are some examples of degenerative retinal diseases. Inflammation is the protective response of the immune system to a harmful stimulus and this stimulus could be in the form of toxic metabolites/chemicals, pathogens, damaged cells, physical, traumatic, ischemic, or other challenges. Inflammatory events are the most likely causes of progressive retinal degenerative conditions.

- retina

- retinal degeneration

- AMD

1. Factors Contributing to Inflammation in Retinal Degenerative Diseases

1.1. Genetic Factors

1.2. Non-Genetic Factors

2. Role of Inflammation in Age-Related Macular Degeneration

3. Role of Inflammation in Inherited Retinal Dystrophies

References

- Singh, M.; Tyagi, S.C. Genes and genetics in eye diseases: A genomic medicine approach for investigating hereditary and inflammatory ocular disorders. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 11, 117–134.

- Melrose, M.A.; Magargal, L.E.; Lucier, A.C. Identical twins with subretinal neovascularization complicating senile macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 1985, 16, 648–651.

- Ahmed, A.U.; Williams, B.R.; Hannigan, G.E. Transcriptional activation of inflammatory genes: Mechanistic insight into selectivity and diversity. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 3087–3111.

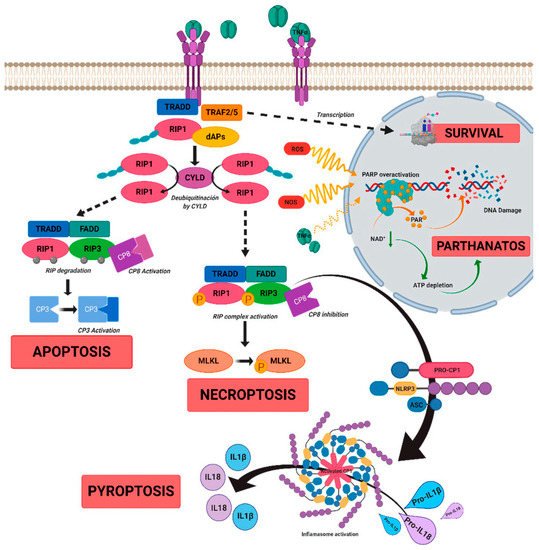

- Olivares-González, L.; Velasco, S.; Campillo, I.; Rodrigo, R. Retinal inflammation, cell death and inherited retinal dystrophies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2096.

- Choudhury, S.R.; Bhootada, Y.; Gorbatyuk, M.S. Caspase-7 ablation modulates UPR, reprograms TRAF2-JNK apoptosis and protects T17M rhodopsin mice from severe retinal degeneration. Cell Death. Dis. 2013, 4, e528.

- Comitato, A.; Sanges, D.; Rossi, A.; Humphries, M.M.; Marigo, V. Activation of Bax in Three Models of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 3555–3561.

- Kunte, M.M.; Choudhury, S.; Manheim, J.F.; Shinde, V.M.; Miura, M.; Chiodo, V.A.; Hauswirth, W.W.; Gorbatyuk, O.S.; Gorbatyuk, M.S. ER Stress Is Involved in T17M Rhodopsin-Induced Retinal Degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 3792–3800.

- Chen, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, Z.-J. (Z)-7,4′-Dimethoxy-6-hydroxy-aurone-4-O-β-glucopyranoside mitigates retinal degeneration in Rd10 mouse model through inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2020, 39, 36–42.

- Murakami, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Roh, M.; Suzuki, J.; Hisatomi, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Miller, J.W.; Vavvas, D.G. Receptor interacting protein kinase mediates necrotic cone but not rod cell death in a mouse model of inherited degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14598–14603.

- Olivares-González, L.; Velasco, S.; Millán, J.M.; Rodrigo, R. Intravitreal administration of adalimumab delays retinal degeneration in rd10 mice. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 13839–13861.

- Malsy, J.; Alvarado, A.C.; Lamontagne, J.O.; Strittmatter, K.; Marneros, A.G. Distinct effects of complement and of NLRP3-and non-NLRP3 inflammasomes for choroidal neovascularization. Elife 2020, 9, e60194.

- Yerramothu, P.; Vijay, A.K.; Willcox, M.D. Inflammasomes, the eye and anti-inflammasome therapy. Eye 2018, 32, 491–505.

- Celkova, L.; Doyle, S.L.; Campbell, M. NLRP3 inflammasome and pathobiology in AMD. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 172–192.

- Gora, I.M.; Ciechanowska, A.; Ladyzynski, P. NLRP3 Inflammasome at the Interface of Inflammation, Endothelial Dysfunction, and Type 2 Diabetes. Cells 2021, 10, 314.

- Wooff, Y.; Man, S.M.; Aggio-Bruce, R.; Natoli, R.; Fernando, N. IL-1 Family Members Mediate Cell Death, Inflammation and Angiogenesis in Retinal Degenerative Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1618.

- Eandi, C.M.; Messance, H.C.; Augustin, S.; Dominguez, E.; Lavalette, S.; Forster, V.; Hu, S.J.; Siquieros, L.; Craft, C.M.; Sahel, J.A.; et al. Subretinal mononuclear phagocytes induce cone segment loss via IL-1β. Elife 2016, 5, e16490.

- Altmann, C.; Schmidt, M.H. The role of microglia in diabetic retinopathy: Inflammation, microvasculature defects and neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 110.

- Blank, T.; Goldmann, T.; Koch, M.; Amann, L.; Schön, C.; Bonin, M.; Pang, S.; Prinz, M.; Burnet, M.; Wagner, J.E.; et al. Early microglia activation precedes photoreceptor degeneration in a mouse model of CNGB1-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Front. Immunol. 2018, 8, 1930.

- Zeng, H.L.; Shi, J.M. The role of microglia in the progression of glaucomatous neurodegeneration—A review. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 11, 143–149.

- Qian, Y.; Zhang, M. The functional roles of IL-33/ST2 axis in ocular diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 5230716.

- Augustine, J.; Pavlou, S.; Ali, I.; Harkin, K.; Ozaki, E.; Campbell, M.; Stitt, A.W.; Xu, H.; Chen, M. IL-33 deficiency causes persistent inflammation and severe neurodegeneration in retinal detachment. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 251.

- Wong, E.K.; Hallam, T.M.; Brocklebank, V.; Walsh, P.R.; Smith-Jackson, K.; Shuttleworth, V.G.; Cox, T.E.; Anderson, H.E.; Barlow, P.N.; Marchbank, K.J.; et al. Functional characterization of rare genetic variants in the N-terminus of complement Factor H in aHUS, C3G, and AMD. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 602284.

- Roshanipour, N.; Bonyadi, M.; Bonyadi, M.H.; Soheilian, M. The effect of complement factor B gene variation on age-related macular degeneration in Iranian patients. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2019, 31, 292–297.

- McKay, G.J.; Patterson, C.C.; Chakravarthy, U.; Dasari, S.; Klaver, C.C.; Vingerling, J.R.; Ho, L.; de Jong, P.T.; Fletcher, A.E.; Young, I.S.; et al. Evidence of association of APOE with age-related macular degeneration-a pooled analysis of 15 studies. Hum. Mutat. 2011, 32, 1407–1416.

- Fritsche, L.G.; Fariss, R.N.; Stambolian, D.; Abecasis, G.R.; Curcio, C.A.; Swaroop, A. Age-related macular degeneration: Genetics and biology coming together. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2014, 15, 151–171.

- Geerlings, M.J.; de Jong, E.K.; den Hollander, A.I. The complement system in age-related macular degeneration: A review of rare genetic variants and implications for personalized treatment. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 84, 65–76.

- Sergejeva, O.; Botov, R.; Liutkevičienė, R.; Kriaučiūnienė, L. Genetic factors associated with the development of age-related macular degeneration. Medicina 2016, 52, 79–88.

- Edwards, A.O.; Ritter, R.; Abel, K.J.; Manning, A.; Panhuysen, C.; Farrer, L.A. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science 2005, 308, 421–424.

- Jakobsdottir, J.; Conley, Y.P.; Weeks, D.E.; Mah, T.S.; Ferrell, R.E.; Gorin, M.B. Susceptibility genes for age related maculopathy on chromosome 10q26. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 77, 389–407.

- Genini, S.; Guziewicz, K.E.; Beltran, W.A.; Aguirre, G.D. Altered miRNA expression in canine retinas during normal development and in models of retinal degeneration. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 172.

- Jablonski, K.A.; Gaudet, A.D.; Amici, S.A.; Popovich, P.G.; Guerau-de-Arellano, M. Control of the Inflammatory Macrophage Transcriptional Signature by miR-155. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159724.

- Woo, S.J.; Ahn, J.; Morrison, M.A.; Ahn, S.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.W.; Park, K.H. Analysis of genetic and environmental risk factors and their interactions in Korean patients with age-related macular degeneration. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132771.

- Ong, S.R.; Crowston, J.G.; Loprinzi, P.D.; Ramulu, P.Y. Physical activity, visual impairment, and eye disease. Eye 2018, 32, 1296–12303.

- Lambert, N.G.; ElShelmani, H.; Singh, M.K.; Mansergh, F.C.; Wride, M.A.; Padilla, M.; Keegan, D.; Hogg, R.E.; Ambati, B.K. Risk factors and biomarkers of age-related macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 54, 64–102.

- Heesterbeek, T.J.; Lorés-Motta, L.; Hoyng, C.B.; Lechanteur, Y.T.; den Hollander, A.I. Risk factors for progression of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2020, 40, 140–170.

- Bomotti, S.; Lau, B.; Klein, B.E.K.; Lee, K.E.; Klein, R.; Duggal, P.; Klein, A.P. Refraction and Change in Refraction Over a 20-Year Period in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 4518–4524.

- Knudtson, M.D.; Klein, R.; Klein, B.E. Physical activity and the 15-year cumulative incidence of age-related macular degeneration: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 1461–1463.

- Hammond, B.R., Jr.; Wooten, B.R.; Snodderly, D.M. Cigarette smoking and retinal carotenoids: Implications for age-relatedmacular degeneration. Vis. Res. 1996, 36, 3003–3009.

- Sastry, B.V.; Hemontolor, M.E. Influence of nicotine and cotinine on retinal phospholipaseA2 and its significance to macular function. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 14, 447–1458.

- Espinosa-Heidmann, D.G.; Suner, I.J.; Catanuto, P.; Hernandez, E.P.; Marin-Castano, M.E.; Cousins, S.W. Cigarette smoke-related oxidants and the development of sub-RPE deposits in an experimental animal model of dry age-related macular degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 729–737.

- Shanmugam, N.; Figarola, J.L.; Li, Y.; Swiderski, P.M.; Rahbar, S.; Natarajan, R. Proinflammatory effects of advanced lipoxidation end products in monocytes. Diabetes 2008, 57, 879–888.

- Moldogazieva, N.T.; Mokhosoev, I.M.; Mel’nikova, T.I.; Porozov, Y.B.; Terentiev, A.A. Oxidative stress and advanced lipoxidation and glycation end products (ALEs and AGEs) in aging and age-related diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 3085756.

- Kauppinen, A.; Paterno, J.J.; Blasiak, J.; Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K. Inflammation and its role in age-related macular degeneration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 1765–1786.

- Copland, D.A.; Theodoropoulou, S.; Liu, J.; Dick, A.D. A perspective of AMD through the eyes of immunology. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, AMD83–AMD92.

- Handa, J.T.; Bowes Rickman, C.; Dick, A.D.; Gorin, M.B.; Miller, J.W.; Toth, C.A.; Ueffing, M.; Zarbin, M.; Farrer, L.A. A systems biology approach towards understanding and treating non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3347.

- Ambati, J.; Atkinson, J.P.; Gelfand, B.D. Immunology of age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 438–451.

- de Jong, E.K.; Geerlings, M.J.; den Hollander, A.I. Age-related macular degeneration. In Genetics and Genomics of Eye Disease. Advancing to Precision Medicine; Academic Press, Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 155–180.

- Sarks, S.H.; Arnold, J.J.; Killingsworth, M.C.; Sarks, J.P. Early drusen formation in the normal and aging eye and their relation to age related maculopathy: A clinicopathological study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 83, 358–368.

- Toomey, C.B.; Kelly, U.; Saban, D.R.; Bowes, R.C. Regulation of age-related macular degeneration-like pathology by complement factor H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E3040–E3049.

- Rashid, K.; Akhtar-Schaefer, I.; Langmann, T. Microglia in retinal degeneration. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1975.

- Alves, C.H.; Fernandes, R.; Santiago, A.R.; Ambrósio, A.F. Microglia contribution to the regulation of the retinal and choroidal vasculature in age-related macular degeneration. Cells 2020, 9, 1217.

- Vessey, K.A.; Waugh, M.; Jobling, A.I.; Phipps, J.A.; Ho, T.; Trogrlic, L.; Greferath, U.; Fletcher, E.L. Assessment of retinal function and morphology in aging Ccl2 knockout mice. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 1238–1252.

- Chinnery, H.R.; McLenachan, S.; Humphries, T.; Kezic, J.M.; Chen, X.; Ruitenberg, M.J.; McMenamin, P.G. Accumulation of murine subretinal macrophages: Effects of age, pigmentation and CX3CR1. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 1769–1776.

- Ronning, K.E.; Karlen, S.J.; Miller, E.B.; Burns, M.E. Molecular profiling of resident and infiltrating mononuclear phagocytes during rapid adult retinal degeneration using single cell. RNA sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4858.

- Levy, O.; Calippe, B.; Lavalette, S.; Hu, S.J.; Raoul, W.; Dominguez, E.; Housset, M.; Paques, M.; Sahel, J.A.; Bemelmans, A.P.; et al. Apolipoprotein E promotes subretinal mononuclear phagocyte survival and chronic inflammation in age-related macular degeneration. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 211–226.

- Sennlaub, F.; Auvynet, C.; Calippe, B.; Lavalette, S.; Poupel, L.; Hu, S.J.; Dominguez, E.; Camelo, S.; Levy, O.; Guyon, E.; et al. CCR2(+) monocytes infiltrate atrophic lesions in age-related macular disease and mediate photoreceptor degeneration in experimental subretinal inflammation in Cx3cr1 deficient mice. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 1775–1793.

- Calippe, B.; Augustin, S.; Beguier, F.; Charles-Messance, H.; Poupel, L.; Conart, J.B.; Hu, S.J.; Lavalette, S.; Fauvet, A.; Rayes, J.; et al. Complement Factor H Inhibits CD47-Mediated Resolution of Inflammation. Immunity 2017, 46, 261–272.

- Ding, X.; Patel, M.; Chan, C.C. Molecular pathology of age-related macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2009, 28, 1–18.

- Kuzmich, N.N.; Sivak, K.V.; Chubarev, V.N.; Porozov, Y.B.; Savateeva-Lyubimova, T.N.; Peri, F. TLR4 signaling pathway modulators as potential therapeutics in inflammation and sepsis. Vaccines 2017, 5, 34.

- Akira, S.; Takeda, K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 499–511.

- Zareparsi, S.; Buraczynska, M.; Branham, K.E.; Shah, S.; Eng, D.; Li, M.; Pawar, H.; Yashar, B.M.; Moroi, S.E.; Lichter, P.R.; et al. Toll-like receptor 4 variant D299G is associated with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 1449–1455.

- Goverdhan, S.V.; Ennis, S.; Hannan, S.R.; Madhusudhana, K.C.; Cree, A.J.; Luff, A.J.; Lotery, A.J. Interleukin-8 promoter polymorphism -251A/T is a risk factor for age-related macular degeneration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 92, 537–540.

- Touhami, S.; Beguier, F.; Augustin, S.; Charles-Messance, H.; Vignaud, L.; Nandrot, E.F.; Reichman, S.; Forster, V.; Mathis, T.; Sahel, J.A.; et al. Chronic exposure to tumor necrosis factor alpha induces retinal pigment epithelium cell dedifferentiation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 85.

- Nielsen, M.K.; Subhi, Y.; Molbech, C.R.; Falk, M.K.; Nissen, M.H.; Sørensen, T.L. Systemic levels of interleukin-6 correlate with progression rate of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 202–208.

- Seddon, J.M.; Gensler, G.; Milton, R.C.; Klein, M.L.; Rifai, N. Association between C-reactive protein and age-related macular degeneration. JAMA 2004, 291, 704–710.

- Nassar, K.; Grisanti, S.; Elfar, E.; Lüke, J.; Lüke, M.; Grisanti, S. Serum cytokines as biomarkers for age-related macular degeneration. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2015, 253, 699–704.

- Miller, A.M.; Xu, D.; Asquith, D.L.; Denby, L.; Li, Y.; Sattar, N.; Baker, A.H.; Mclnnes, I.B.; Liew, F.Y. IL-33 reduces the development of atherosclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 339–346.

- Gallenga, C.E.; Lonardi, M.; Pacetti, S.; Violanti, S.S.; Tassinari, P.; Di Virgilio, F.; Perri, P. Molecular Mechanisms Related to Oxidative Stress in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 848.

- Hartong, D.T.; Berson, E.L.; Dryja, T.P. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 2006, 368, 1795–1809.

- Broadgate, S.; Yu, J.; Downes, S.M.; Halford, S. Unravelling the genetics of inherited retinal dystrophies: Past, present and future. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 59, 53–96.

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 7204–7218.

- Jiao, H.; Natoli, R.; Valter, K.; Provis, J.M.; Rutar, M. Spatiotemporal Cadence of Macrophage Polarisation in a Model of Light-Induced Retinal Degeneration. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143952.

- McMenamin, P.G.; Saban, D.R.; Dando, S.J. Immune cells in the retina and choroid: Two different tissue environments that require different defenses and surveillance. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2019, 70, 85–98.

- Streit, W.J.; Mrak, R.E.; Griffin, W.S. Microglia and neuroinflammation: A pathological perspective. J. Neuroinflamm. 2004, 1, 14.

- Karlstetter, M.; Scholz, R.; Rutar, M.; Wong, W.T.; Provis, J.M.; Langmann, T. Retinal microglia: Just bystander or target for therapy? Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2015, 45, 30–57.

- Noailles, A.; Fernández-Sánchez, L.; Lax, P.; Cuenca, N. Microglia activation in a model of retinal degeneration and TUDCA neuroprotective effects. J. Neuroinflamm. 2014, 11, 186.

- Arroba, A.I.; Valverde, Á.M. Modulation of microglia in the retina: New insights into diabetic retinopathy. Acta Diabetol. 2017, 54, 527–533.

- Morizane, Y.; Morimoto, N.; Fujiwara, A.; Kawasaki, R.; Yamashita, H.; Ogura, Y.; Shiraga, F. Incidence and causes of visual impairment in Japan: The first nation-wide complete enumeration survey of newly certified visually impaired individuals. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 63, 26–33.