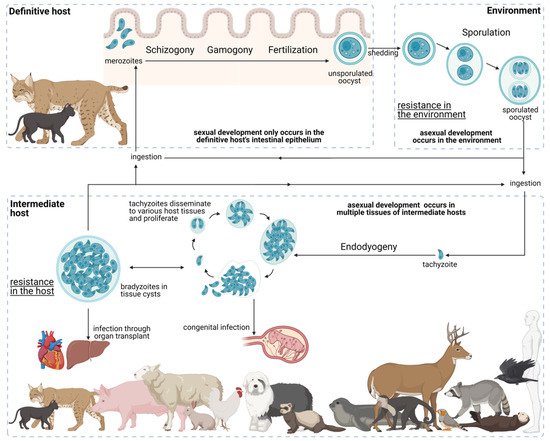

Toxoplasma gondii is a ubiquitous zoonotic parasite with an obligatory intracellular lifestyle. It relies on a specialized set of cytoskeletal and secretory organelles for host cell invasion. When infecting its felid definitive host, T. gondii undergoes sexual reproduction in the intestinal epithelium, producing oocysts that are excreted with the feces and sporulate in the environment. In other hosts and/or tissues, T. gondii multiplies by asexual reproduction. Rapidly dividing tachyzoites expand through multiple tissues, particularly nervous and muscular tissues, and eventually convert to slowly dividing bradyzoites which produce tissue cysts, structures that evade the immune system and remain infective within the host. Infection normally occurs through ingestion of sporulated oocysts or tissue cysts. While T. gondii is able to infect virtually all warm-blooded animals, most infections in humans are asymptomatic, with clinical disease occurring most often in immunocompromised hosts or fetuses carried by seronegative mothers that are infected during pregnancy.

- Toxoplasma gondii

- toxoplasmosis

- parasite

- tissue cyst

- endodyogeny

- lytic cycle

- life cycle

- oocyst

- Apicomplexa

1. Toxoplasma gondii: A Successful Parasite

2. A Prevalent and Silent Infection

2.1. Epidemiology and Transmission

2.2. Infection and Disease

3. An Apicomplexa Parasite

| Taxon | Classical Classification 1 | Updated Classification 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Kingdom | Protozoa | Chromista |

| Subkingdom | Dictyozoa | Harosa |

| Infrakingdom | Neozoa | Halvaria |

| Superphylum | Alveolata | Alveolata |

| Phylum | Apicomplexa | Myozoa |

| Infraphylum | Sporozoa | Apicomplexa |

| Superclass | Coccidia | Sporozoa |

| Class | Eucoccidea | Coccidiomorphea |

| Order | Eucoccidiorida | Eimeriida |

| Family | Sarcocystidae | Sarcocystidae |

| Genus | Toxoplasma | Toxoplasma |

| Species | Toxoplasma gondii | Toxoplasma gondii |

4. Genetic Diversity: One Species, Many Strains

5. One Parasite, Several Specialized Eukaryotic Cells

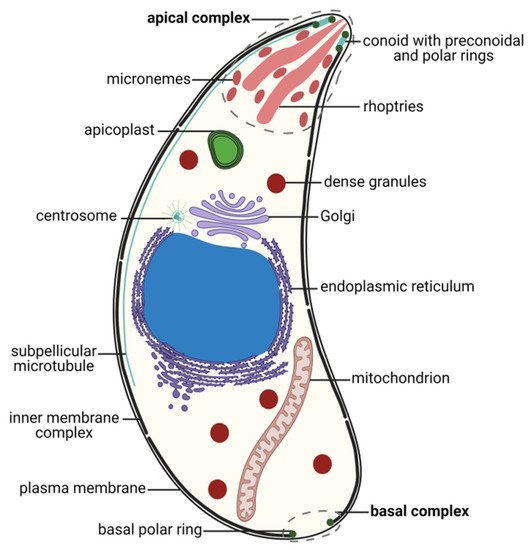

5.1. Zoites, Motile Stages

5.2. Non-Motile and Gamete Stages

6. The Complex Toxoplasma gondii Life Cycle: A Path to Success

6.1. Development in the Definitive Host

6.2. Environmental Development

6.3. Development in the Intermediate Host

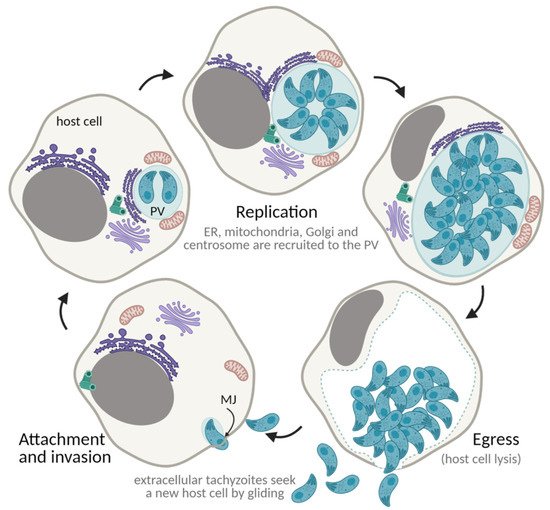

7. The Toxoplasma gondii Lytic Cycle: An Efficient Proliferation Strategy

7.1. Gliding Motility

7.2. Attachment and Invasion

7.3. Establishment of the Parasitophorous Vacuole

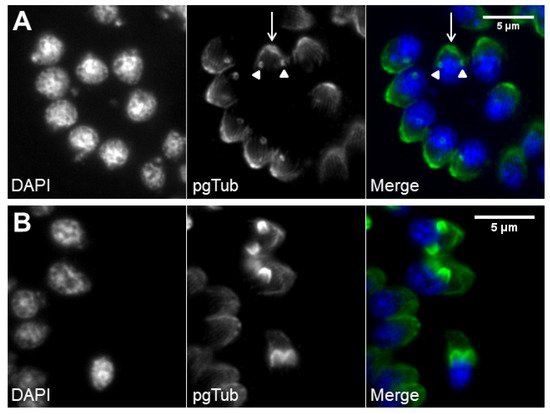

7.4. Proliferation through Endodyogeny

7.5. Egress and Repeat

8. The Tissue Cyst

9. Conclusions and Prospects

References

- Jiménez-Ruiz, E.; Wong, E.H.; Pall, G.S.; Meissner, M. Advantages and disadvantages of conditional systems for characterization of essential genes in Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitology 2014, 141, 1390–1398.

- Nicolle, C.; Manceaux, L. Sur Une Infection à Corps de Leishman (Ou Organismes Voisins) Du Gondi. Comptes Rendus Séances L’académie Sci. 1908, 147, 763–766.

- Splendore, A. Un Nuovo Protozoa Parassita de’ Conigli. Rev. Soc. Sci. 1908, 3, 109–112.

- Nicolle, C.; Manceaux, L. Sur Un Protozoaire Nouveau Du Gondi. Comptes Rendus Séances L’académie Sci. 1909, 148, 369–372.

- McLeod, R.; Van Tubbergen, C.; Montoya, J.G.; Petersen, E. Human Toxoplasma Infection, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 9780123964816.

- Stelzer, S.; Basso, W.; Silván, J.B.; Ortega-Mora, L.-M.; Maksimov, P.; Gethmann, J.; Conraths, F.; Schares, G. Toxoplasma gondii infection and toxoplasmosis in farm animals: Risk factors and economic impact. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2019, 15, e00037.

- Black, M.W.; Boothroyd, J.C. Lytic Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 607–623.

- Aguirre, A.A.; Longcore, T.; Barbieri, M.; Dabritz, H.; Hill, D.; Klein, P.N.; Lepczyk, C.; Lilly, E.L. The one health approach to toxoplasmosis: Epidemiology, Control, and Prevention Strategies. Ecohealth 2019, 16, 378–390.

- Wang, J.-L.; Zhang, N.-Z.; Li, T.-T.; He, J.-J.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Zhu, X.-Q. Advances in the development of Anti-Toxoplasma Gondii Vaccines: Challenges, opportunities, and perspectives. Trends Parasitol. 2019, 35, 239–253.

- World Malaria Report 2020: 20 Years of Global Progress and Challenges; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Gray, J.; Zintl, A.; Hildebrandt, A.; Hunfeld, K.P.; Weiss, L. Zoonotic babesiosis: Overview of the disease and novel aspects of pathogen identity. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2010, 1, 3–10.

- Beugnet, F.; Moreau, Y. Babesiosis. OIE Rev. Sci. Tech. 2015, 34, 627–639.

- Tzipori, S.; Ward, H. Cryptosporidiosis: Biology, pathogenesis and disease. Microbes Infect. 2002, 4, 1047–1058.

- Reichel, M.P.; Alejandra Ayanegui-Alcérreca, M.; Gondim, L.F.P.; Ellis, J.T. What is the global economic impact of neospora caninum in cattle-The Billion Dollar Question. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013, 43, 133–142.

- Álvarez-García, G.; García-Lunar, P.; Gutiérrez-Expósito, D.; Shkap, V.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Dynamics of Besnoitia Besnoiti infection in cattle. Parasitology 2014, 141, 1419–1435.

- Robert-Gangneux, F.; Dardé, M.L. Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 264–296.

- Parise, M.E.; Hotez, P.J.; Slutsker, L. Neglected parasitic infections in the United States: Needs and opportunities. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 90, 783–785.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Congenital toxoplasmosis. In ECDC. Annual Epidemiological Report for 2018; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021.

- Flegr, J.; Prandota, J.; Sovičková, M.; Israili, Z.H. Toxoplasmosis-A global threat. Correlation of latent toxoplasmosis with specific disease burden in a set of 88 countries. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90203.

- Smith, D.D.; Frenkel, J.K. Prevalence of antibodies to toxoplasma gondii in wild mammals of missouri and east central kansas: Biologic and ecologic considerations of transmission. J. Wildl. Dis. 1995, 31, 15–21.

- De Thoisy, B.; Demar, M.; Aznar, C.; Carme, B. Ecological Correlates of Toxoplasma Gondii Exposure in Free-Ranging Neotropical Mammals. J. Wildl. Dis. 2003, 39, 456–459.

- Dabritz, H.A.; Miller, M.A.; Gardner, I.A.; Packham, A.E.; Atwill, E.R.; Conrad, P.A. Risk factors for Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Wild Rodents from Central Coastal California and a review of T. Gondii Prevalence in Rodents. J. Parasitol. 2008, 94, 675–683.

- Barros, M.; Cabezón, O.; Dubey, J.P.; Almería, S.; Ribas, M.P.; Escobar, L.E.; Ramos, B.; Medina-Vogel, G. Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Wild Mustelids and Cats across an Urban-Rural Gradient. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199085.

- Dubey, J.P.; Murata, F.H.A.; Cerqueira-Cézar, C.K.; Kwok, O.C.H. Public health and economic importance of Toxoplasma Gondii Infections in Goats: The Last Decade. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 132, 292–307.

- Dubey, J.P.; Murata, F.H.A.; Cerqueira-Cézar, C.K.; Kwok, O.C.H. Toxoplasma Gondii Infections in Horses, Donkeys, and Other Equids: The Last Decade. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 132, 492–499.

- Dubey, J.P.; Murata, F.H.A.; Cerqueira-Cézar, C.K.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Yang, Y.R. Public Health Significance of Toxoplasma Gondii Infections in Cattle: 2009–2020. J. Parasitol. 2020, 106, 772–788.

- Montazeri, M.; Mikaeili Galeh, T.; Moosazadeh, M.; Sarvi, S.; Dodangeh, S.; Javidnia, J.; Sharif, M.; Daryani, A. The Global Serological Prevalence of Toxoplasma Gondii in Felids during the Last Five Decades (1967–2017): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 82.

- Shapiro, K.; Bahia-Oliveira, L.; Dixon, B.; Dumètre, A.; de Wit, L.A.; VanWormer, E.; Villena, I. Environmental Transmission of Toxoplasma Gondii: Oocysts in Water, Soil and Food. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2019, 15, e00049.

- Maleki, B.; Ahmadi, N.; Olfatifar, M.; Gorgipour, M.; Taghipour, A.; Abdoli, A.; Khorshidi, A.; Foroutan, M.; Mirzapour, A. Toxoplasma Oocysts in the Soil of Public Places Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 115, 471–481.

- Moré, G.; Maksimov, P.; Pardini, L.; Herrmann, D.C.; Bacigalupe, D.; Maksimov, A.; Basso, W.; Conraths, F.J.; Schares, G.; Venturini, M.C. Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Sentinel and Free-Range Chickens from Argentina. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 184, 116–121.

- Guo, M.; Dubey, J.P.; Hill, D.; Buchanan, R.L.; Ray Gamble, H.; Jones, J.L.; Pradhan, A.K. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Meat Animals and Meat Products Destined for Human Consumption. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 457–476.

- Dubey, J.P.; Frenkel, J.K. Immunity to Feline Toxoplasmosis: Modification by Administration of Corticosteroids. Vet. Pathol. 1974, 11, 350–379.

- Kapperud, G.; Jenum, P.A.; Stray-Pedersen, B.; Melby, K.K.; Eskild, A.; Eng, J. Risk Factors for Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Pregnancy: Results of a Prospective Case-Control Study in Norway. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1996, 144, 405–412.

- Cook, A.J.; Gilbert, R.E.; Buffolano, W.; Zufferey, J.; Petersen, E.; Jenum, P.A.; Foulon, W.; Semprini, A.E.; Dunn, D.T. Sources of Toxoplasma Infection in Pregnant Women: European Multicentre Case-Control Study. European Research Network on Congenital Toxoplasmosis. BMJ 2000, 321, 142–147.

- Berger, F.; Goulet, V.; Le Strat, Y.; Desenclos, J.C. Toxoplasmosis among Pregnant Women in France: Risk Factors and Change of Prevalence between 1995 and 2003. Rev. Epidemiol. Sante Publique 2009, 57, 241–248.

- Jones, J.L.; Dargelas, V.; Roberts, J.; Press, C.; Remington, J.S.; Montoya, J.G. Risk Factors for Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 878–884.

- Ramakrishnan, C.; Maier, S.; Walker, R.A.; Rehrauer, H.; Joekel, D.E.; Winiger, R.R.; Basso, W.U.; Grigg, M.E.; Hehl, A.B.; Deplazes, P.; et al. An Experimental Genetically Attenuated Live Vaccine to Prevent Transmission of Toxoplasma Gondii by Cats. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1474.

- Dubey, J.P. Advances in the Life Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 1998, 28, 1019–1024.

- Kean, B.H.; Kimball, A.C.; Christenson, W.N. An Epidemic of Acute Toxoplasmosis. JAMA 1969, 208, 1002–1004.

- Desmonts, G.; Couvreur, J.; Alison, F.; Baudelot, J.; Gerbeaux, J.; Lelong, M. Étude Épidémiologique Sur La Toxoplasmose: De l’influence de La Cuisson Des Viandes de Boucherie Sur La Fréquence de l’infection Humaine. Rev. Fr. Études Clin. Biol. 1965, 10, 952–958.

- Hill, D.; Coss, C.; Dubey, J.P.; Wroblewski, K.; Sautter, M.; Hosten, T.; Muñoz-Zanzi, C.; Mui, E.; Withers, S.; Boyer, K.; et al. Identification of a Sporozoite-Specific Antigen from Toxoplasma Gondii. J. Parasitol. 2011, 97, 328–337.

- Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasmosis in Sheep-The Last 20 Years. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 163, 1–14.

- Ryning, F.W.; McLeod, R.; Maddox, J.C.; Hunt, S.; Remington, J.S. Probable Transmission of Toxoplasma Gondii by Organ Transplantation. Ann. Intern. Med. 1979, 90, 47–49.

- Sacks, J.J.; Roberto, R.R.; Brooks, N.F. Toxoplasmosis Infection Associated With Raw Goat’s Milk. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1982, 248, 1728–1732.

- Fernàndez-Sabé, N.; Cervera, C.; Fariñas, M.C.; Bodro, M.; Muñoz, P.; Gurguí, M.; Torre-Cisneros, J.; Martín-Dávila, P.; Noblejas, A.; Len, Ó.; et al. Risk Factors, Clinical Features, and Outcomes of Toxoplasmosis in Solid-Organ Transplant Recipients: A Matched Case-Control Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 355–361.

- Dubey, J.P.; Verma, S.K.; Ferreira, L.R.; Oliveira, S.; Cassinelli, A.B.; Ying, Y.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Tuo, W.; Chiesa, O.A.; Jones, J.L. Detection and Survival of Toxoplasma Gondii in Milk and Cheese from Experimentally Infected Goats. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 1747–1753.

- Milne, G.; Webster, J.P.; Walker, M. Toxoplasma Gondii: An Underestimated Threat? Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 959–969.

- Montoya, J.G.; Liesenfeld, O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004, 363, 1965–1976.

- Calero-Berna, R.; Gennari, S.M. Clinical Toxoplasmosis in Dogs and Cats: An Update. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 54.

- Dunay, I.R.; Gajurel, K.; Dhakal, R.; Liesenfeld, O.; Montoya, J.G. Treatment of Toxoplasmosis: Historical Perspective, Animal. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 31, 1–33.

- McPhillie, M.J.; Zhou, Y.; Hickman, M.R.; Gordon, J.A.; Weber, C.R.; Li, Q.; Lee, P.J.; Amporndanai, K.; Johnson, R.M.; Darby, H.; et al. Potent Tetrahydroquinolone Eliminates Apicomplexan Parasites. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 1–27.

- Brandão, G.P.; Melo, M.N.; Caetano, B.C.; Carneiro, C.M.; Silva, L.A.; Vitor, R.W.A. Susceptibility to Re-Infection in C57BL/6 Mice with Recombinant Strains of Toxoplasma Gondii. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 128, 433–437.

- Lindsay, D.S.; Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasma Gondii: The Changing Paradigm of Congenital Toxoplasmosis. Parasitology 2011, 138, 1829–1831.

- Zulpo, D.L.; Sammi, A.S.; dos Santos, J.R.; Sasse, J.P.; Martins, T.A.; Minutti, A.F.; Cardim, S.T.; de Barros, L.D.; Navarro, I.T.; Garcia, J.L. Toxoplasma Gondii: A Study of Oocyst Re-Shedding in Domestic Cats. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 249, 17–20.

- Blaga, R.; Aubert, D.; Thébault, A.; Perret, C.; Geers, R.; Thomas, M.; Alliot, A.; Djokic, V.; Ortis, N.; Halos, L.; et al. Toxoplasma Gondii in Beef Consumed in France: Regional Variation in Seroprevalence and Parasite Isolation. Parasite 2019, 26, 77.

- Alves, B.F.; Oliveira, S.; Soares, H.S.; Pena, H.F.J.; Conte-Junior, C.A.; Gennari, S.M. Isolation of Viable Toxoplasma Gondii from Organs and Brazilian Commercial Meat Cuts of Experimentally Infected Pigs. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 1331–1335.

- Dubey, J.P.; Cerqueira-Cézar, C.K.; Murata, F.H.A.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Hill, D.; Yang, Y.; Su, C. All about Toxoplasma Gondii Infections in Pigs: 2009–2020. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 288, 109185.

- Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasma Gondii Infections in Chickens (Gallus Domesticus): Prevalence, Clinical Disease, Diagnosis and Public Health Significance. Zoonoses Public Health 2010, 57, 60–73.

- Conrad, P.A.; Miller, M.A.; Kreuder, C.; James, E.R.; Mazet, J.; Dabritz, H.; Jessup, D.A.; Gulland, F.; Grigg, M.E. Transmission of Toxoplasma: Clues from the Study of Sea Otters as Sentinels of Toxoplasma Gondii Flow into the Marine Environment. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 1155–1168.

- Burgess, T.L.; Tinker, M.T.; Miller, M.A.; Bodkin, J.L.; Murray, M.J.; Saarinen, J.A.; Nichol, L.M.; Larson, S.; Conrad, P.A.; Johnson, C.K. Defining the Risk Landscape in the Context of Pathogen Pollution: Toxoplasma Gondii in Sea Otters along the Pacific Rim. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171178.

- Shapiro, K.; VanWormer, E.; Packham, A.; Dodd, E.; Conrad, P.A.; Miller, M. Type X Strains of Toxoplasma Gondii Are Virulent for Southern Sea Otters (Enhydra Lutris Nereis) and Present in Felids from Nearby Watersheds. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 286, 20191334.

- Frénal, K.; Dubremetz, J.F.; Lebrun, M.; Soldati-Favre, D. Gliding Motility Powers Invasion and Egress in Apicomplexa. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 645–660.

- McFadden, G.I.; Yeh, E. The Apicoplast: Now You See It, Now You Don’t. Int. J. Parasitol. 2017, 47, 137–144.

- Walker, G.; Dorrell, R.G.; Schlacht, A.; Dacks, J.B. Eukaryotic Systematics: A User’s Guide for Cell Biologists and Parasitologists. Parasitology 2011, 138, 1638–1663.

- Šlapeta, J.; Morin-Adeline, V. Apicomplexa Levine 1970, Sporozoa Leucart. 1879. Available online: http://tolweb.org/Apicomplexa/2446/2011.05.18 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Koreny, L.; Zeeshan, M.; Barylyuk, K.; Tromer, E.C.; van Hooff, J.J.E.; Brady, D.; Ke, H.; Chelaghma, S.; Ferguson, D.J.P.; Eme, L.; et al. Molecular Characterization of the Conoid Complex in Toxoplasma Reveals Its Conservation in All Apicomplexans, Including Plasmodium Species. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001081.

- Cavalier-Smith, T. Kingdom Protozoa and Its 18 Phyla. Microbiol. Rev. 1993, 57, 953–994.

- Cavalier-Smith, T. A Revised Six-Kingdom System of Life. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1998, 73, 203–266.

- Taylor, M.A.; Coop, R.L.; Wall, R.L. Veterinary Parasitology; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-0-470-67162-7.

- Ruggiero, M.A.; Gordon, D.P.; Orrell, T.M.; Bailly, N.; Bourgoin, T.; Brusca, R.C.; Cavalier-Smith, T.; Guiry, M.D.; Kirk, P.M. A Higher Level Classification of All Living Organisms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119248.

- Rees, T.; Vandepitte, L.; Vanhoorne, B.; Decock, W. All Genera of the World: An Overview and Estimates Based on the March 2020 Release of the Interim Register of Marine and Nonmarine Genera (IRMNG). Megataxa 2020, 1, 123–140.

- Howe, D.K.; Sibley, L.D. Toxoplasma Gondii Comprises Three Clonal Lineages: Correlation of Parasite Genotype with Human Disease. J. Infect. Dis. 1995, 172, 1561–1566.

- Su, C.; Evans, D.; Cole, R.H.; Kissinger, J.C.; Ajioka, J.W.; Sibley, L.D. Recent Expansion of Toxoplasma through Enhanced Oral Transmission. Science 2003, 299, 414–416.

- Khan, A.; Fux, B.; Su, C.; Dubey, J.P.; Darde, M.L.; Ajioka, J.W.; Rosenthal, B.M.; Sibley, L.D. Recent Transcontinental Sweep of Toxoplasma Gondii Driven by a Single Monomorphic Chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 14872–14877.

- Pena, H.F.J.; Marvulo, M.F.V.; Horta, M.C.; Silva, M.A.; Silva, J.C.R.; Siqueira, D.B.; Lima, P.A.C.P.; Vitaliano, S.N.; Gennari, S.M. Isolation and Genetic Characterisation of Toxoplasma Gondii from a Red-Handed Howler Monkey (Alouatta Belzebul), a Jaguarundi (Puma Yagouaroundi), and a Black-Eared Opossum (Didelphis Aurita) from Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 175, 377–381.

- Fux, B.; Nawas, J.; Khan, A.; Gill, D.B.; Su, C.; Sibley, L.D. Toxoplasma Gondii Strains Defective in Oral Transmission Are Also Defective in Developmental Stage Differentiation. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 2580–2590.

- Mercier, A.; Ajzenberg, D.; Devillard, S.; Demar, M.P.; de Thoisy, B.; Bonnabau, H.; Collinet, F.; Boukhari, R.; Blanchet, D.; Simon, S.; et al. Human Impact on Genetic Diversity of Toxoplasma Gondii: Example of the Anthropized Environment from French Guiana. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011, 11, 1378–1387.

- Khan, A.; Ajzenberg, D.; Mercier, A.; Demar, M.; Simon, S.; Dardé, M.L.; Wang, Q.; Verma, S.K.; Rosenthal, B.M.; Dubey, J.P.; et al. Geographic Separation of Domestic and Wild Strains of Toxoplasma Gondii in French Guiana Correlates with a Monomorphic Version of Chromosome1a. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3182.

- Ferguson, D.J.P.; Dubremetz, J.-F. The Ultrastructure of Toxoplasma gondii. In Toxoplasma Gondii; Weiss, L.M., Kim, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 19–59. ISBN 9780123964816.

- Harding, C.R.; Frischknecht, F. The Riveting Cellular Structures of Apicomplexan Parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 979–991.

- Attias, M.; Teixeira, D.E.; Benchimol, M.; Vommaro, R.C.; Crepaldi, P.H.; De Souza, W. The Life-Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii Reviewed Using Animations. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 1–13.

- Melo, E.J.L.; Attias, M.; De Souza, W. The Single Mitochondrion of Tachyzoites of Toxoplasma Gondii. J. Struct. Biol. 2000, 130, 27–33.

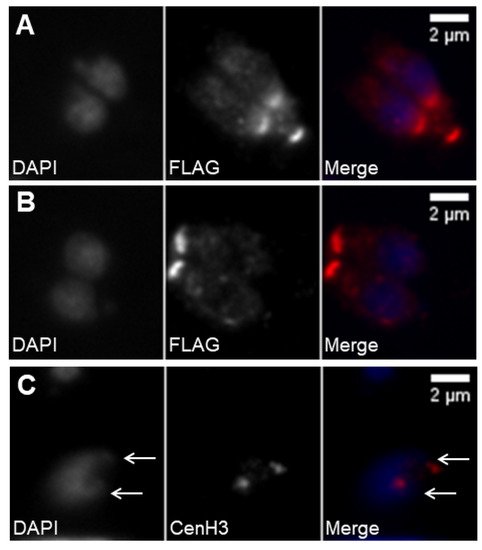

- Striepen, B.; Crawford, M.J.; Shaw, M.K.; Tilney, L.G.; Seeber, F.; Roos, D.S. The Plastid of Toxoplasma Gondii Is Divided by Association with the Centrosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 151, 1423–1434.

- Chen, C.T.; Gubbels, M.J. The Toxoplasma Gondii Centrosome Is the Platform for Internal Daughter Budding as Revealed by a Nek1 Kinase Mutant. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 3344–3355.

- Brooks, C.F.; Johnsen, H.; van Dooren, G.G.; Muthalagi, M.; Lin, S.S.; Bohne, W.; Fischer, K.; Striepen, B. The Toxoplasma Apicoplast Phosphate Translocator Links Cytosolic and Apicoplast Metabolism and Is Essential for Parasite Survival. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 7, 62–73.

- Janouškovec, J.; Horák, A.; Oborník, M.; Lukeš, J.; Keeling, P.J. A Common Red Algal Origin of the Apicomplexan, Dinoflagellate, and Heterokont Plastids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 10949–10954.

- Joiner, K.A.; Roos, D.S. Secretory Traffic in the Eukaryotic Parasite Toxoplasma Gondii: Less Is More. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 157, 557–563.

- Lebrun, M.; Carruthers, V.B.; Cesbron-Delauw, M.-F. Toxoplasma Secretory Proteins and Their Roles in Cell Invasion and Intracellular Survival. In Toxoplasma Gondii; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 389–453. ISBN 9780123964816.

- Kentaro, K. How Does Toxoplama Gondii Invade Host Cells? J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2018, 80, 1702–1706.

- Dubey, J.P.; Lindsay, D.S.; Speer, C.A. Structures of Toxoplasma Gondii Tachyzoites, Bradyzoites, and Sporozoites and Biology and Development of Tissue Cysts. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 267–299.

- Russell, D.G.; Burns, R.G. The Polar Ring of Coccidian Sporozoites: A Unique Microtubule-Organizing Centre. J. Cell Sci. 1984, 65, 193–207.

- Nichols, B.A.; Chiappino, M.L. Cytoskeleton of Toxoplasma Gondii 1. J. Protozool. 1987, 34, 217–226.

- Morrissette, N.S.; Sibley, L.D. Cytoskeleton of Apicomplexan Parasites. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66, 21–38.

- Hu, K.; Johnson, J.; Florens, L.; Fraunholz, M.; Suravajjala, S.; DiLullo, C.; Yates, J.; Roos, D.S.; Murray, J.M. Cytoskeletal Components of an Invasion Machine-The Apical Complex of Toxoplasma Gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2, e13.

- Katris, N.J.; van Dooren, G.G.; McMillan, P.J.; Hanssen, E.; Tilley, L.; Waller, R.F. The Apical Complex Provides a Regulated Gateway for Secretion of Invasion Factors in Toxoplasma. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004074.

- Mann, T.; Beckers, C. Characterization of the Subpellicular Network, a Filamentous Membrane Skeletal Component in the Parasite Toxoplasma Gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2001, 115, 257–268.

- Hu, K. Organizational Changes of the Daughter Basal Complex during the Parasite Replication of Toxoplasma Gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e10.

- Delbac, F.; Sänger, A.; Neuhaus, E.M.; Stratmann, R.; Ajioka, J.W.; Toursel, C.; Herm-Götz, A.; Tomavo, S.; Soldati, T.; Soldati, D. Toxoplasma Gondii Myosins B/C: One Gene, Two Tails, Two Localizations, and a Role in Parasite Division. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 155, 613–623.

- Gubbels, M.-J.; Vaishnava, S.; Boot, N.; Dubremetz, J.-F.; Striepen, B. A MORN-Repeat Protein Is a Dynamic Component of the Toxoplasma Gondii Cell Division Apparatus. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 2236–2245.

- Heaslip, A.T.; Dzierszinski, F.; Stein, B.; Hu, K. TgMORN1 Is a Key Organizer for the Basal Complex of Toxoplasma Gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000754.

- Lorestani, A.; Ivey, F.D.; Thirugnanam, S.; Busby, M.A.; Marth, G.T.; Cheeseman, I.M.; Gubbels, M.-J. Targeted Proteomic Dissection of Toxoplasma Cytoskeleton Sub-Compartments Using MORN1. Cytoskeleton 2012, 69, 1069–1085.

- Knoll, L.J.; Tomita, T.; Weiss, L.M. Bradyzoite Development. In Toxoplasma Gondii; Weiss, L.M., Kim, K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 521–549. ISBN 9780123964816.

- Jacobs, L.; Remington, J.S.; Melton, M.L. The Resistance of the Encysted Form of Toxoplasma Gondii. J. Parasitol. 1960, 46, 11.

- Popiel, I.; Gold, M.C.; Booth, K.S. Quantification of Toxoplasma Gondii Bradyzoites. J. Parasitol. 1996, 82, 330–332.

- Di Genova, B.M.; Wilson, S.K.; Dubey, J.P.; Knoll, L.J. Intestinal Delta-6-Desaturase Activity Determines Host Range for Toxoplasma Sexual Reproduction. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000364.

- Freyre, A.; Dubey, J.P.; Smith, D.D.; Frenkel, J.K. Gondii Oocyst-Induced Infections. J. Parasitol. 1989, 75, 750–755.

- Dubey, J.P. Oocyst Shedding by Cats Fed Isolated Bradyzoites and Comparison of Infectivity of Bradyzoites of the VEG Strain Toxoplasma Gondii to Cats and Mice. J. Parasitol. 2001, 87, 215–219.

- Dubey, J.P. Comparative Infectivity of Oocysts and Bradyzoites of Toxoplasma Gondii for Intermediate (Mice) and Definitive (Cats) Hosts. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 140, 69–75.

- Tomasina, R.; Francia, M.E. The Structural and Molecular Underpinnings of Gametogenesis in Toxoplasma Gondii. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 1–8.

- Dubey, J.P.; Frenkel, J.K. Cyst-Induced Toxoplasmosis in Cats. J. Protozool. 1972, 19, 155–177.

- Speer, C.A.; Dubey, J.P. Ultrastructural Differentiation of Toxoplasma Gondii Schizonts (Types B to E) and Gamonts in the Intestines of Cats Fed Bradyzoites. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 193–206.

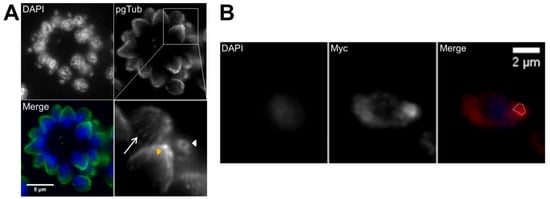

- Francia, M.E.; Striepen, B. Cell Division in Apicomplexan Parasites. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 125–136.

- Dubey, J.P. Duration of Immunity to Shedding of Toxoplasma Gondii Oocysts by Cats. J. Parasitol. 1995, 81, 410–415.

- Fritz, H.M.; Bowyer, P.W.; Bogyo, M.; Conrad, P.A.; Boothroyd, J.C. Proteomic Analysis of Fractionated Toxoplasma Oocysts Reveals Clues to Their Environmental Resistance. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29955.

- Ferguson, D.J.P. Toxoplasma Gondii and Sex: Essential or Optional Extra? Trends Parasitol. 2002, 18, 351–355.

- Dubey, J.P. Pathogenicity and Infectivity of Toxoplasma Gondii Oocysts for Rats. J. Parasitol. 1996, 82, 951–956.

- Dubey, R.; Harrison, B.; Dangoudoubiyam, S.; Bandini, G.; Cheng, K.; Kosber, A.; Agop-nersesian, C.; Howe, D.K.; Samuelson, J.; Ferguson, D.J.P.; et al. Differential Roles for Inner Membrane Complex Proteins across Toxoplasma Gondii and Sarcocystis Neurona Development. mSphere 2017, 2, 1–19.

- Freppel, W.; Ferguson, D.J.P.; Shapiro, K.; Dubey, J.P.; Puech, P.H.; Dumètre, A. Structure, Composition, and Roles of the Toxoplasma Gondii Oocyst and Sporocyst Walls. Cell Surf. 2019, 5, 100016.

- King, C.A. Cell Motility of Sporozoan Protozoa. Parasitol. Today 1988, 4, 315–319.

- Håkansson, S.; Morisaki, H.; Heuser, J.; Sibley, L.D. Time-Lapse Video Microscopy of Gliding Motility in Toxoplasma Gondii Reveals a Novel, Biphasic Mechanism of Cell Locomotion. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 3539–3547.

- Dobrowolski, J.M.; Sibley, L.D. Toxoplasma Invasion of Mammalian Cells Is Powered by the Actin Cytoskeleton of the Parasite. Cell 1996, 84, 933–939.

- Dobrowolski, J.M.; Carruthers, V.B.; Sibley, L.D. Participation of Myosin in Gliding Motility and Host Cell Invasion by Toxoplasma Gondii. Mol. Microbiol. 1997, 26, 163–173.

- Meissner, M.; Schlüter, D.; Soldati, D. Role of Toxoplasma Gondii Myosin a in Powering Parasite Gliding and Host Cell Invasion. Science 2002, 298, 837–840.

- Opitz, C.; Soldati, D. “The Glideosome”: A Dynamic Complex Powering Gliding Motion and Host Cell Invasion by Toxoplasma Gondii. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 45, 597–604.

- Brossier, F.; Jewett, T.J.; Lovett, J.L.; Sibley, L.D. C-Terminal Processing of the Toxoplasma Protein MIC2 Is Essential for Invasion into Host Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 6229–6234.

- Gras, S.; Jimenez-Ruiz, E.; Klinger, C.M.; Schneider, K.; Klingl, A.; Lemgruber, L.; Meissner, M. An Endocytic-Secretory Cycle Participates in Toxoplasma Gondii in Motility. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000060.

- Soldati, D.; Meissner, M. Toxoplasma as a Novel System for Motility. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004, 16, 32–40.

- Mineo, J.R.; Kasper, L.H. Attachment of Toxoplasma Gondii to Host Cells Involves Major Surface Protein, SAG-1 (P-30). Exp. Parasitol. 1994, 79, 11–20.

- Jacquet, A.; Coulon, L.; De Nève, J.; Daminet, V.; Haumont, M.; Garcia, L.; Bollen, A.; Jurado, M.; Biemans, R. The Surface Antigen SAG3 Mediates the Attachment of Toxoplasma Gondii to Cell-Surface Proteoglycans. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2001, 116, 35–44.

- Rabenau, K.E.; Sohrabi, A.; Tripathy, A.; Reitter, C.; Ajioka, J.W.; Tomley, F.M.; Carruthers, V.B. TgM2AP Participates in Toxoplasma Gondii Invasion of Host Cells and Is Tightly Associated with the Adhesive Protein TgMIC2. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 41, 537–547.

- Cérède, O.; Dubremetz, J.F.; Soête, M.; Deslée, D.; Vial, H.; Bout, D.; Lebrun, M. Synergistic Role of Micronemal Proteins in Toxoplasma Gondii Virulence. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 453–463.

- Whitelaw, J.A.; Latorre-Barragan, F.; Gras, S.; Pall, G.S.; Leung, J.M.; Heaslip, A.; Egarter, S.; Andenmatten, N.; Nelson, S.R.; Warshaw, D.M.; et al. Surface Attachment, Promoted by the Actomyosin System of Toxoplasma Gondii Is Important for Efficient Gliding Motility and Invasion. BMC Biol. 2017, 15, 1–23.

- Alexander, D.L.; Mital, J.; Ward, G.E.; Bradley, P.; Boothroyd, J.C. Identification of the Moving Junction Complex of Toxoplasma Gondii: A Collaboration between Distinct Secretory Organelles. PLoS Pathog. 2005, 1, e17.

- Carruthers, V.; Boothroyd, J.C. Pulling Together: An Integrated Model of Toxoplasma Cell Invasion. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2007, 10, 83–89.

- Mordue, D.G.; Desai, N.; Dustin, M.; Sibley, L.D. Proteins on the Basis of Their Membrane Anchoring. J. Exp. Med 1999, 190, 1783–1792.

- Charron, A.J.; Sibley, L.D. Molecular Partitioning during Host Cell Penetration by Toxoplasma Gondii. Traffic 2004, 5, 855–867.

- Walker, M.E.; Hjort, E.E.; Smith, S.S.; Tripathi, A.; Hornick, J.E.; Hinchcliffe, E.H.; Archer, W.; Hager, K.M. Toxoplasma Gondii Actively Remodels the Microtubule Network in Host Cells. Microbes Infect. 2008, 10, 1440–1449.

- Sweeney, K.R.; Morrissette, N.S.; Lachapelle, S.; Blader, I.J. Host Cell Invasion by Toxoplasma Gondii Is Temporally Regulated by the Host Microtubule Cytoskeleton. Eukaryot. Cell 2010, 9, 1680–1689.

- Cardoso, R.; Nolasco, S.; Goncalves, J.; Cortes, H.C.; Leitao, A.; Soares, H. Besnoitia Besnoiti and Toxoplasma Gondii: Two Apicomplexan Strategies to Manipulate the Host Cell Centrosome and Golgi Apparatus. Parasitology 2014, 141, 1436–1454.

- Sibley, L.D.; Niesman, I.R.; Parmley, S.F.; Cesbron-Delauw, M.F. Regulated Secretion of Multi-Lamellar Vesicles Leads to Formation of a Tubulovesicular Network in Host-Cell Vacuoles Occupied by Toxoplasma Gondii. J. Cell Sci. 1995, 108, 1669–1677.

- Mercier, C.; Dubremetz, J.-F.; Rauscher, B.; Lecordier, L.; Sibley, L.D.; Cesbron-Delauw, M.-F. Biogenesis of Nanotubular Network in Toxoplasma Parasitophorous Vacuole Induced by Parasite Proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 2002, 13, 2397–2409.

- De Melo, E.J.T.; de Carvalho, T.U.; de Souza, W. Penetration of Toxoplasma Gondii into Host Cells Induces Changes in the Distribution of the Mitochondria and the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Cell Struct. Funct. 1992, 17, 311–317.

- Melo, E.J.T.; De Souza, W. Relationship between the Host Cell Endoplasmic Reticulum and the Parasitophorous Vacuole Containing Toxoplasma Gondii. Cell Struct. Funct. 1997, 22, 317–323.

- Sinai, A.P.; Webster, P.; Joiner, K.A. Association of Host Cell Endoplasmic Reticulum and Mitochondria with the Toxoplasma Gondii Parasitophorous Vacuole Membrane: A High Affinity Interaction. J. Cell Sci. 1997, 110, 2117–2128.

- Melo, E.J.T.; Carvalho, T.M.U.; de Souza, W. Behaviour of Microtubules in Cells Infected with Toxoplasma Gondii. Biocell 2001, 25, 53–59.

- Sehgal, A.; Bettiol, S.; Pypaert, M.; Wenk, M.R.; Kaasch, A.; Blader, I.J.; Joiner, K.A.; Coppens, I. Peculiarities of Host Cholesterol Transport to the Unique Intracellular Vacuole Containing Toxoplasma. Traffic 2005, 6, 1125–1141.

- Coppens, I.; Dunn, J.D.; Romano, J.D.; Pypaert, M.; Zhang, H.; Boothroyd, J.C.; Joiner, K.A. Toxoplasma Gondii Sequesters Lysosomes from Mammalian Hosts in the Vacuolar Space. Cell 2006, 125, 261–274.

- Coppens, I.; Sinai, A.P.; Joiner, K.A. Toxoplasma Gondii Exploits Host Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor- Mediated Endocytosis for Cholesterol Acquisition. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 149, 167–180.

- Romano, J.D.; Sonda, S.; Bergbower, E.; Smith, M.E.; Coppens, I. Toxoplasma Gondii Salvages Sphingolipids from the Host Golgi through the Rerouting of Selected Rab Vesicles to the Parasitophorous Vacuole. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 1974–1995.

- Nolan, S.J.; Romano, J.D.; Coppens, I. Host Lipid Droplets: An Important Source of Lipids Salvaged by the Intracellular Parasite Toxoplasma Gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006362.

- Romano, J.D.; Nolan, S.J.; Porter, C.; Ehrenman, K.; Hartman, E.J.; Hsia, R.-C.; Coppens, I. The Parasite Toxoplasma Sequesters Diverse Rab Host Vesicles within an Intravacuolar Network. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 4235–4254.

- Jones, T.C.; Hirsch, J.G. The Interaction between Toxoplasma Gondii and Mammalian Cells: II. The Absence of Lysosomal Fusion with Phagocytic Vacuoles Containing Living Parasites. J. Exp. Med. 1972, 136, 1173–1194.

- Carvalho, C.S.; Melo, E.J.T. Acidification of the Parasitophorous Vacuole Containing Toxoplasma Gondii in the Presence of Hydroxyurea. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2006, 78, 475–484.

- Radke, J.R.; Striepen, B.; Guerini, M.N.; Jerome, M.E.; Roos, D.S.; White, M.W. Defining the Cell Cycle for the Tachyzoite Stage of Toxoplasma Gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2001, 115, 165–175.

- Sheffield, H.G.; Melton, M.L. The Fine Structure and Reproduction of Toxoplasma Gondii. J. Parasitol. 1968, 54, 209–226.

- Hu, K.; Mann, T.; Striepen, B.; Beckers, C.J.M.; Roos, D.S.; Murray, J.M. Daughter Cell Assembly in the Protozoan Parasite Toxoplasma Gondii. Mol. Biol. Cell 2002, 13, 593–606.

- Hartmann, J.; Hu, K.; He, C.Y.; Pelletier, L.; Roos, D.S.; Warren, G. Golgi and Centrosome Cycles in Toxoplasma Gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006, 145, 125–127.

- Nishi, M.; Hu, K.; Murray, J.M.; Roos, D.S. Organellar Dynamics during the Cell Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 1559–1568.

- Anderson-White, B.; Beck, J.R.; Chen, C.-T.; Meissner, M.; Bradley, P.J.; Gubbels, M.-J. Cytoskeleton Assembly in Toxoplasma Gondii Cell Division. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 298, 1–31.

- Gubbels, M.-J.; White, M.; Szatanek, T. The Cell Cycle and Toxoplasma Gondii Cell Division: Tightly Knit or Loosely Stitched? Int. J. Parasitol. 2008, 38, 1343–1358.

- Francia, M.E.; Jordan, C.N.; Patel, J.D.; Sheiner, L.; Demerly, J.L.; Fellows, J.D.; de Leon, J.C.; Morrissette, N.S.; Dubremetz, J.F.; Striepen, B. Cell Division in Apicomplexan Parasites Is Organized by a Homolog of the Striated Rootlet Fiber of Algal Flagella. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001444.

- Caldas, L.; de Souza, W. A Window to Toxoplasma Gondii Egress. Pathogens 2018, 7, 69.

- Kafsack, B.F.C.; Pena, J.D.O.; Coppens, I.; Ravindran, S.; Boothroyd, J.C.; Carruthers, V.B. Rapid Membrane Disruption by a Perforin-like Protein Facilitates Parasite Exit from Host Cells. Science 2009, 323, 530–533.

- Okada, T.; Marmansari, D.; Li, Z.M.; Adilbish, A.; Canko, S.; Ueno, A.; Shono, H.; Furuoka, H.; Igarashi, M. A Novel Dense Granule Protein, GRA22, Is Involved in Regulating Parasite Egress in Toxoplasma Gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2013, 189, 5–13.

- Gras, S.; Jackson, A.; Woods, S.; Pall, G.; Whitelaw, J.; Leung, J.M.; Ward, G.E.; Roberts, C.W.; Meissner, M. Parasites Lacking the Micronemal Protein MIC2 Are Deficient in Surface Attachment and Host Cell Egress, but Remain Virulent In Vivo. Wellcome Open Res. 2017, 2, 1–26.

- LaFavers, K.A.; Márquez-Nogueras, K.M.; Coppens, I.; Moreno, S.N.J.; Arrizabalaga, G. A Novel Dense Granule Protein, GRA41, Regulates Timing of Egress and Calcium Sensitivity in Toxoplasma Gondii. Cell. Microbiol. 2017, 19, e12749.

- Schultz, A.J.; Carruthers, V.B. Toxoplasma Gondii LCAT Primarily Contributes to Tachyzoite Egress. mSphere 2018, 3, 1–10.

- Frénal, K.; Marq, J.B.; Jacot, D.; Polonais, V.; Soldati-Favre, D. Plasticity between MyoC- and MyoA-Glideosomes: An Example of Functional Compensation in Toxoplasma Gondii Invasion. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004504.

- Graindorge, A.; Frénal, K.; Jacot, D.; Salamun, J.; Marq, J.B.; Soldati-Favre, D. The Conoid Associated Motor MyoH Is Indispensable for Toxoplasma Gondii Entry and Exit from Host Cells. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005388.

- Jacot, D.; Tosetti, N.; Pires, I.; Stock, J.; Graindorge, A.; Hung, Y.F.; Han, H.; Tewari, R.; Kursula, I.; Soldati-Favre, D. An Apicomplexan Actin-Binding Protein Serves as a Connector and Lipid Sensor to Coordinate Motility and Invasion. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 731–743.

- Bisio, H.; Soldati-Favre, D. Signaling Cascades Governing Entry into and Exit from Host Cells by Toxoplasma Gondii. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 73, 579–599.

- Endo, T.; Sethi, K.K.; Piekarski, G. Toxoplasma Gondii: Calcium Lonophore A23187-Mediated Exit of Trophozoites from Infected Murine Macrophages. Exp. Parasitol. 1982, 53, 179–188.

- Lourido, S.; Tang, K.; David Sibley, L. Distinct Signalling Pathways Control Toxoplasma Egress and Host-Cell Invasion. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 4524–4534.

- Radke, J.R.; Guerini, M.N.; Jerome, M.; White, M.W. A Change in the Premitotic Period of the Cell Cycle Is Associated with Bradyzoite Differentiation in Toxoplasma Gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2003, 131, 119–127.

- Watts, E.; Zhao, Y.; Dhara, A.; Eller, B.; Patwardhan, A.; Sinai, P. Novel Approaches Reveal That Toxoplasma Gondii Bradyzoites within Tissue Cysts Are Dynamic and Replicating Entities In Vivo. MBio 2015, 6, 1–24.

- Weiss, L.M.; Kim, K. The Development and Biology of Bradyzoites of Toxoplasma Gondii. Front. Biosci. 2000, 5, 391–405.

- Ferguson, D.J.P.; Hutchison, W.M. An Ultrastructural Study of the Early Development and Tissue Cyst Formation of Toxoplasma Gondii in the Brains of Mice. Parasitol. Res. 1987, 73, 483–491.

- Boothroyd, J.C.; Black, M.; Bonnefoy, S.; Hehl, A.; Knoll, L.J.; Manger, I.D.; Ortega-Barria, E.; Tomavo, S. Genetic and Biochemical Analysis of Development in Toxoplasma Gondii. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 1997, 352, 1347–1354.

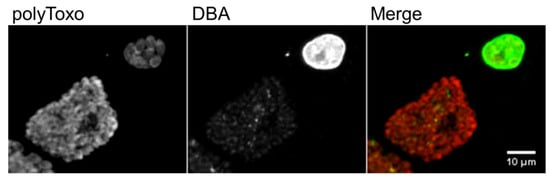

- Paredes-Santos, T.C.; Tomita, T.; Yan Fen, M.; de Souza, W.; Attias, M.; Vommaro, R.C.; Weiss, L.M. Development of Dual Fluorescent Stage Specific Reporter Strain of Toxoplasma Gondii to Follow Tachyzoite and Bradyzoite Development In Vitro and In Vivo. Microbes Infect. 2016, 18, 39–47.

- Paredes-Santos, T.C.; Martins-Duarte, E.S.; Vitor, R.W.A.; de Souza, W.; Attias, M.; Vommaro, R.C. Spontaneous Cystogenesis In Vitro of a Brazilian Strain of Toxoplasma Gondii. Parasitol. Int. 2013, 62, 181–188.

- Lane, A.; Soete, M.; Dubremetz, J.F.; Smith, J.E. Toxoplasma Gondii: Appearance of Specific Markers during the Development of Tissue Cysts In Vitro. Parasitol. Res. 1996, 82, 340–346.

- Soete, M.; Fortier, B.; Camus, D.; Dubremetz, J.F. Toxoplasma Gondii: Kinetics of Bradyzoite-Tachyzoite Interconversion In Vitro. Exp. Parasitol. 1993, 76, 259–264.

- Soete, M.; Camus, D.; Dubrametz, J.F. Experimental Induction of Bradyzoite-Specific Antigen Expression and Cyst Formation by the RH Strain of Toxoplasma Gondii In Vitro. Exp. Parasitol. 1994, 78, 361–370.

- Weiss, L.M.; Laplace, D.; Takvorian, P.M.; Tanowitz, H.B.; Cali, A.; Wittner, M. A Cell Culture System for Study of the Development of Toxoplasma Gondii Bradyzoites. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 1995, 42, 150–157.

- Bohne, W.; Heesemann, J.; Gross, U. Induction of Bradyzoite-Specific Toxoplasma Gondii Antigens in Gamma Interferon-Treated Mouse Macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1993, 61, 1141–1145.

- Bohne, W.; Heesemann, J.; Gross, U. Reduced Replication of Toxoplasma Gondii Is Necessary for Induction of Bradyzoite-Specific Antigens: A Possible Role for Nitric Oxide in Triggering Stage Conversion. Infect. Immun. 1994, 62, 1761–1767.

- Fox, B.A.; Gigley, J.P.; Bzik, D.J. Toxoplasma Gondii Lacks the Enzymes Required for de Novo Arginine Biosynthesis and Arginine Starvation Triggers Cyst Formation. Int. J. Parasitol. 2004, 34, 323–331.

- Ihara, F.; Nishikawa, Y. Starvation of Low-Density Lipoprotein-Derived Cholesterol Induces Bradyzoite Conversion in Toxoplasma Gondii. Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 1–5.

- Tomavo, S.; Boothroyd, J.C. Interconnection between Organellar Functions, Development and Drug Resistance in the Protozoan Parasite, Toxoplasma Gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 1995, 25, 1293–1299.

- Kirkman, L.A.; Weiss, L.M.; Kim, K. Cyclic Nucleotide Signaling in Toxoplasma Gondii Bradyzoite Differentiation. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 148–153.

- Eaton, M.S.; Weiss, L.M.; Kim, K. Cyclic Nucleotide Kinases and Tachyzoite—Bradyzoite Transition in Toxoplasma Gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 2006, 36, 107–114.

- Sullivan, W.J.; Narasimhan, J.; Bhatti, M.M.; Wek, R.C. Parasite-Specific EIF2 (Eukaryotic Initiation Factor-2) Kinase Required for Stress-Induced Translation Control. Biochem. J. 2004, 380, 523–531.

- Sullivan, W.J.; Hakimi, M.A. Histone Mediated Gene Activation in Toxoplasma Gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006, 148, 109–116.

- Bougdour, A.; Maubon, D.; Baldacci, P.; Ortet, P.; Bastien, O.; Bouillon, A.; Barale, J.C.; Pelloux, H.; Ménard, R.; Hakimi, M.A. Drug Inhibition of HDAC3 and Epigenetic Control of Differentiation in Apicomplexa Parasites. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 953–966.

- Radke, J.R.; Behnke, M.S.; Mackey, A.J.; Radke, J.B.; Roos, D.S.; White, M.W. The Transcriptome of Toxoplasma Gondii. BMC Biol. 2005, 3, 26.

- Song, X.; Lin, M.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q. Toxoplasma Gondii Metacaspase 2 Is an Important Factor That Influences Bradyzoite Formation in the Pru Strain. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 2287–2298.

- Huang, S.; Holmes, M.J.; Radke, J.B.; Hong, D.-P.; Liu, T.; White, M.W.; Sullivan, W.J. Toxoplasma Gondii AP2IX-4 Regulates Gene Expression during Bradyzoite Development. Host Microbe Biol. 2017, 2, 1–16.

- Radke, J.B.; Worth, D.; Hong, D.; Huang, S.; Sullivan, W.J.; Wilson, E.H.; White, M.W. Transcriptional Repression by ApiAP2 Factors Is Central to Chronic Toxoplasmosis. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007035.

- Farhat, D.C.; Swale, C.; Dard, C.; Cannella, D.; Ortet, P.; Barakat, M.; Sindikubwabo, F.; Belmudes, L.; De Bock, P.J.; Couté, Y.; et al. A MORC-Driven Transcriptional Switch Controls Toxoplasma Developmental Trajectories and Sexual Commitment. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 570–583.

- Waldman, B.S.; Schwarz, D.; Wadsworth, M.H.; Saeij, J.P.; Shalek, A.K.; Lourido, S. Identification of a Master Regulator of Differentiation in Toxoplasma. Cell 2020, 180, 359–372.

- Hong, D.; Radke, J.B.; White, M.W. Opposing Transcriptional Mechanisms Regulate Toxoplasma Development. Mol. Biol. Physiol. 2017, 2, 1–15.

- Croken, M.M.; Qiu, W.; White, M.W.; Kim, K. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of Toxoplasma Gondii Expression Datasets Links Cell Cycle Progression and the Bradyzoite Developmental Program. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 1–13.

- Behnke, M.S.; Wootton, J.C.; Lehmann, M.M.; Radke, J.B.; Lucas, O.; Nawas, J.; Sibley, L.D.; White, M.W. Coordinated Progression through Two Subtranscriptomes Underlies the Tachyzoite Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12354.