Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Rita Xu and Version 4 by Rita Xu.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) are aggressive soft tissue sarcomas (STS) with nerve sheath differentiation and a tendency to metastasize. Although occurring at an incidence of 0.001% in the general population, they are relatively common in individuals with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), for whom the lifetime risk approaches 10%.

- malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

- MEK inhibitor

- multi-disciplinary management

1. Introduction

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) are malignant, locally aggressive soft tissue sarcomas (STS) with nerve sheath differentiation and a high propensity to metastasize. They are rare in the general population, with an approximate lifetime incidence of 0.001% (e.g., 1/100,000) [1]. However, in individuals with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), the lifetime risk of developing one of these tumors is approximately 10%. Up to 50% of all MPNSTs occur in patients with NF1 [1]. All-told, MPNST comprise 5–10% of soft tissue sarcomas and are one of the most common nonrhabdomyosarcomatous soft tissue sarcomas (NRSTS) in pediatric patients [1]. Whereas about 10–20% of all MPNSTs are diagnosed in children [1], there is no difference between children and adults in tumor location, size, or histological grade–although adults are more likely to have more than one primary tumor at the time of diagnosis [1].

2. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors in Context as Soft Tissue Sarcomas

MPNSTs are a form of sarcoma–that is, a tumor arising from cells of mesenchymal origin that have undergone malignant transformation. Mesenchymal cells display at least partial differentiation towards a connective tissue lineage–a broad term that includes, among others, muscle, adipose, bone, cartilage, vascular, and nervous tissue. Sarcomas are therefore classified based on the specific type of mesenchymal tissue they have arisen from and/or the tissue to which they bear a histopathological resemblance. Sarcomas are broadly divided into either soft tissue or bony tissue. Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) together comprise 7% of pediatric solid tumors [2] and are divided into those which either display or do not display differentiation towards striated muscle: rhabdomyosarcomas and nonrhabdomyosarcomatous soft tissue sarcomas (NRSTS), respectively. The category of NRSTS contains a diverse array of sarcomas, as any STS which does not display striated-muscle differentiation is necessarily included in this broad grouping.

According to the Fifth Edition of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s Classification of Tumors Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors, [3] nerve sheath tumors are divided into those which are benign (e.g., schwannomas, neurofibromas including plexiform neurofibromas, perineuriomas, etc.) and those which are malignant, of which MPNSTs form a major subset [4]. Although sometimes used synonymously with the terms “malignant schwannoma” or “neurofibrosarcoma,” MPNST is the most accurate moniker, as these tumors may originate from and/or display differentiation towards any peripheral nerve sheath cell–not only Schwann cells [5].

3. MPNST Pathophysiology

Specific NRSTS may occur more commonly within the context of particular cancer predisposition syndromes (e.g., leiomyosarcoma in hereditary/germline retinoblastoma, due to RB1 mutation) [6]. Alternatively, certain NRSTS may be part of the diagnostic criteria for a given disorder (e.g., rhabdoid tumors in rhabdoid tumor predisposition syndrome, due to SMARCB1/INI1 mutation) [7]. MPNSTs are the former, as their presence does not specifically define the presence of Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), nor are they required for its diagnosis. Still, they are considered a hallmark of NF1 when present. Similarly, many NRSTS are characterized by specific chromosomal translocations or mutations. The presence of such changes typically has one of two results. Firstly, a fusion protein may be generated, allowing for activation of a constitutively expressed kinase or transcription factor independent of ligand binding [8]. Secondly, the mutation may cause a deleterious loss-of-function in a tumor suppressor or cell-cycle regulator gene [9]. These alterations are detectable via polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and their presence helps to facilitate diagnosis within this heterogeneous group of tumors. MPNSTS are most often characterized by the second variety of mutations–specifically by loss of function of the tumor suppressor gene NF1.

Although bi-allelic NF1 inactivation or mutation appears necessary for MPNST development, it does not seem sufficient [10]. Plexiform neurofibromas were shown to develop in this context [11], but malignant transformation appears to require additional abnormalities–specifically, CDKN2A, EGFR, SUZ12, and TP53 have all been implicated [12]. EGFR, SUZ12, and TP53 mutations are all seen in the context of MPNSTs, but not in plexiform neurofibromas or atypical neurofibromas [12]. Similarly, CDKN2A loss is seen in the vast majority of atypical neurofibromas and in low-grade MPNSTs–but not in plexiform neurofibromas [13]. Therefore, one potential model for MPNST development proposes that bi-allelic NF1 loss occurs in nerve-sheath precursor cells, resulting in benign neurofibroma formation. Subsequently, loss of CDKN2A occurs, promoting the development of an atypical neurofibroma–followed by additional mutations in EGFR, SUZ12, and/or TP53, which cause transformation into an MPNST [10].

Relationship of MPNST to Neurofibromatosis Type 1

NF1 is a neurocutaneous cancer predisposition syndrome, which may arise either de novo or be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. A diagnosis of NF1 may be established when an individual meets the National Institutes of Health diagnostic criteria (provided in Table 1). It is characterized by deleterious alterations in the NF1 tumor suppressor gene at 17q11.2, resulting in heterozygous, loss-of-function mutations. Therefore, the production and/or function of its gene product, the protein neurofibromin, is subsequently impaired [14]. This protein interacts with several key cellular pathways and has multiple functions–the most germane of which is its role as a critical tumor suppressor gene via negative regulation of the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway [9][15]. Loss-of-function mutations in NF1, therefore, enable constitutive activation of this pathway, with resultant cell growth and proliferation. Patients with NF1 possess only a single functional copy of the NF1 gene (e.g., the “first hit”), with loss of the second copy acting as an oncogenic “second hit” and thereby allowing constitutive activation of this pathway [9]. Patients with NF1 are therefore at increased risk for multiple neoplastic processes–including MPNSTs [14]. A particular characteristic of NF1 is the extreme heterogeneity of its clinical manifestations, which may vary wildly even among members of the same kindred [16]. No specific alteration of the NF1 gene is specifically associated with the NF1 syndrome, and over 500 discrete mutations were identified [16]. This variability may be due both to the large size of the NF1 gene, which lends itself to a greater frequency of mutations, as well as the large number of possible means in which the function or amount of neurofibromin produced may be affected [16]. Genotype-phenotype correlations do exist for some specific mutations, but these constitute the minority of cases [17].

Table 1. National Institutes of Health diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 1 [18].

| In an individual who does not have a parent diagnosed with NF1, two or more are required to make a diagnosis of NF1: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| If an individual has a parent who meets the above diagnostic criteria, a diagnosis of NF1 may be made in that individual if one or more of the above criteria are present. |

Though their presence is a hallmark of NF1, the presence of an MPNST does not ipso facto indicate a diagnosis of NF1. Although the most common neoplasms seen in patients with NF1 are benign neurofibromas, MPNSTs are the most common malignant neoplasm in this population, occurring in approximately 10% of patients with NF1 [16]. Conversely, as many as half of all MPNSTs are seen in patients with NF1 [1]. Although many MPNSTs are therefore sporadic, a diagnosis of NF1 is the primary known risk factor. Moreover, among those patients with NF1, a family history of NF1 and MPNST appears to be associated with an approximately three-fold greater risk of developing an MPNST in that patient [19]. Patients with whole-gene deletions of NF1, subcutaneous neurofibromas, or a larger number of plexiform neurofibromas are at particular risk of developing MPNST [20][21]. Compared to patients with sporadic MPNSTs, patients with NF1-associated MPNSTs also present them at an earlier age–typically in the second-to-fourth decades of life [22]. Besides a diagnosis of NF1, the other primary known risk factor for MPNST development is radiation exposure, typically in the context of a secondary malignant neoplasm occurring following radiotherapy [23].

In most series, patients with either a diagnosis of NF1 or prior radiotherapy have shown a worse overall survival compared to those with sporadic MPNSTs—likely due to the greater propensity towards metastases and/or local invasion demonstrated by tumors in these patients [23][24][25]. However, the presence of NF1 itself does not directly appear to be the causative risk factor for these poorer outcomes–instead, patients with NF1 tend to have larger tumors, which are more challenging to fully resect [26]. The survival gap does appear to be narrowing, however, with patients with NF1-related MPNSTs faring better in studies performed more recently—though still not as well as those with sporadic MPNSTs [24].

4. Characteristics of MPNSTs And Differentiation from Plexiform Neurofibromas

4.1. Clinical Features

Patients with MPNSTs typically present with a history of a progressively expanding soft-tissue mass, which may or may not be painful [5]. In particular, the development of new neurological symptoms (e.g., hypoesthesia or dysesthesia), pain, and/or enlargement of an existing plexiform neurofibroma should raise suspicion for malignant transformation into an MPNST [18]. Symptoms are otherwise relatively non-specific and may be related to the disease site, e.g., neurologic compromise in the event of invasion into a nerve plexus or mass-effect due to tumor size/location [5].

4.2. Radiology

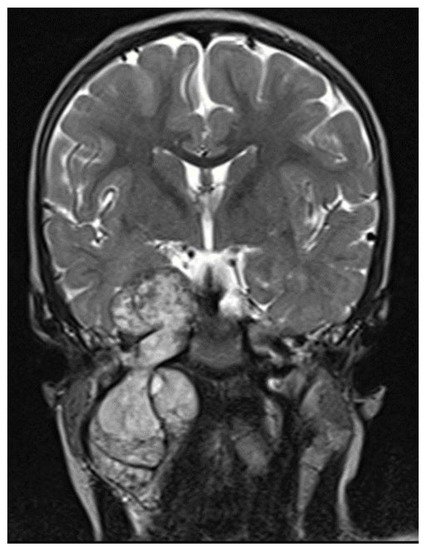

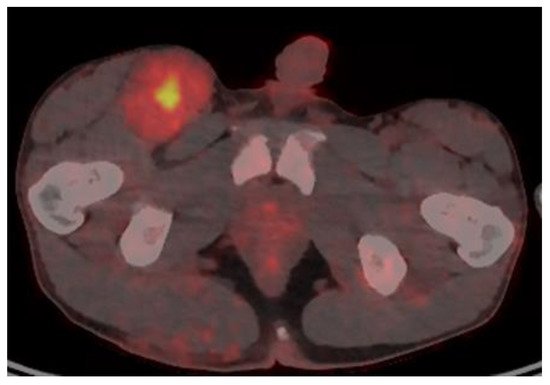

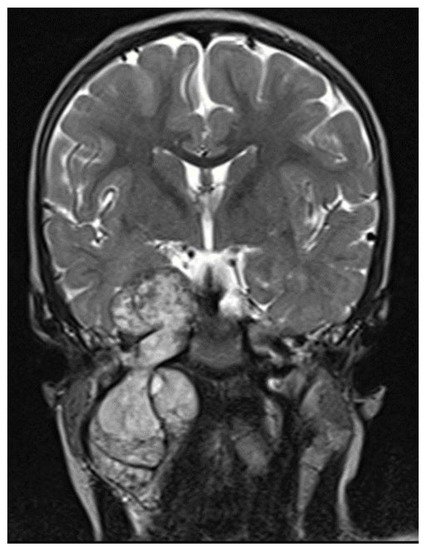

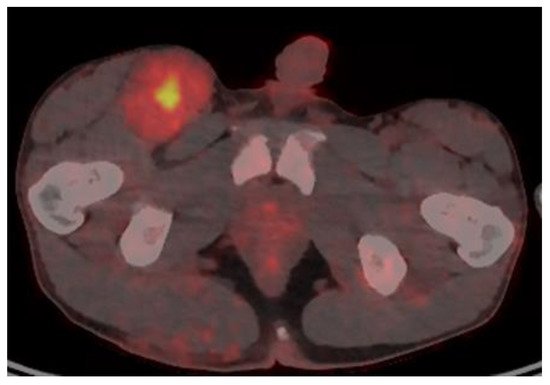

Imaging studies are necessary to delineate tumor extent and may also be of some use in differentiating MPNSTs versus plexiform neurofibromas. On MRI, features such as surrounding peritumoral edema, irregular and/or locally invasive margins, and intra-tumoral heterogeneity appear to be more indicative of MPNSTs (See Figure 1). However, the reported sensitivity and specificity of such findings are quite variable–ranging from less than 20% to over 90% [27][28][29]. Because MPNSTs exhibit higher metabolic activity than plexiform neurofibromas, 18F-FDG PET/CT may be useful in discriminating between these two entities (See Figure 2). Although some degree of overlap exists, standard uptake values (SUVs) of 1–4 tend to indicate benign tumors, while SUVs of 3–21 suggest the presence of MPNST [30][31][32]. Depending on the threshold used, sensitivity and specificity are greater than 90% and 70%, respectively, for the detection of MPNSTs [30][31][32]. A tumor SUV of greater than 1.5-times that of normal hepatic tissue was also separately shown to be both a sensitive and specific indicator of MPNSTs [33].

Figure 1. MRI T2 images, intratumor heterogeneity.

Figure 2. 18F-FDG PET/CT of a patient with NF1 and an MPNST of the right groin, with a maximal SUV of 7.

4.3. Histopathology

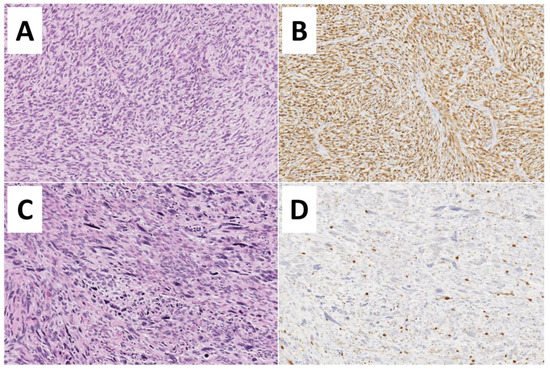

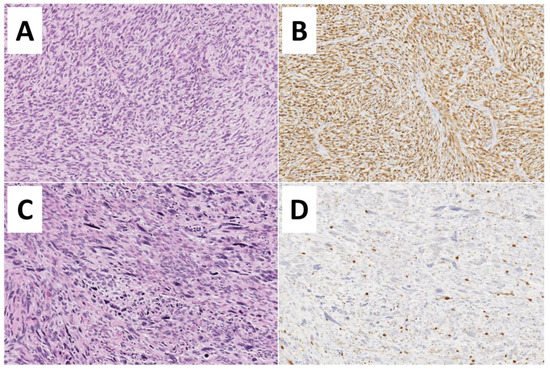

Although clinical and radiological features may be suggestive, definitive diagnosis of an MPNST requires histologic examination. This is complicated, however, by the absence of specific pathognomonic histopathological features, and diagnosis may be challenging [34]. A clear origin from either a peripheral nerve or a neurofibroma strongly aids in diagnosis [5]. Additionally, specific histologic features should be present, including fascicles with alternating, marble-like cellularity, palisade/rosette-like arrangements, and asymmetric spindle cells [5]. Based on the presence of high amounts of mitotic figures and necrosis, MPNSTs may be classified as high-grade or, conversely in the absence of necrosis/fewer mitotic figures, may be classified as low-grade (Figure 2).

Low-grade MPNSTs are sometimes difficult to histologically differentiate from benign plexiform neurofibromas [35]. Moreover, multiple patterns may exist in a single tumor, necessitating careful and complete examination [35]. A biopsy specimen may be insufficient to characterize the tumor adequately, and resection is preferred where possible [10]. However, in cases where the primary tumor is unresectable, percutaneous image-guided core-needle biopsy was shown to be highly accurate in differentiating benign versus malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors [36] and may therefore be a reasonable option. The need to obtain adequate tissue for examination is counterbalanced by the potential for nerve injury. The risk of neurological deficits was reported as being as high as 60% in some series [37] and entirely absent in others [36]. This discrepancy likely arises secondary to the greater precision allowed by more recent diagnostic techniques, specifically, image guidance [36]. Immunohistochemical staining may include S100, Ki67, TP53, CD34, p16, and H3K27me3 (trimethylation at lysine 27 of histone H3) [35]. The interested reader is referred to an excellent review article on the histopathological diagnosis of nerve sheath tumors in general, including MPNSTs [38], see Figure 3.

Figure 3. Histopathological features of Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors—MPNSTs. (A,B) Low-grade MPNST composed of a spindle cell proliferation with increased cellularity, mild cytological atypia, few mitoses (3 to 9 mitoses per 10 high-power fields), but no evidence of necrosis (Hematoxylin and Eosin, 200×). Diffuse immunoreactivity for S100-protein is noted (200×). (C,D) High-grade MPNST showing marked hypercellularity, nuclear pleomorphism, necrosis, and numerous mitoses (more than 10 mitoses per 10 high-power fields) (Hematoxylin and Eosin, 200×). Only focal S100-protein positivity is observed.

References

- Amirian, E.S.; Goodman, J.C.; New, P.; Scheurer, M.E. Pediatric and Adult Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: An Analysis of Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2014, 116, 609–616.

- Childhood Soft Tissue Sarcoma Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version—National Cancer Institute. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/soft-tissue-sarcoma/hp/child-soft-tissue-treatment-pdq (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours; International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Lyon, France, 2020; ISBN 978-92-832-4502-5.

- Fletcher, C.D.M.; Bridge, J.A.; Hogendoorn, P.C.W.; Mertens, F. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone; International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Lyon, France, 2020; ISBN 9789283224341.

- Ferrari, A.; Bisogno, G.; Carli, M. Management of Childhood Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor. Pediatr. Drugs 2007, 9, 239–248.

- Kleinerman, R.A.; Tucker, M.A.; Abramson, D.H.; Seddon, J.M.; Tarone, R.E.; Fraumeni, J.F.J. Risk of Soft Tissue Sarcomas by Individual Subtype in Survivors of Hereditary Retinoblastoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007, 99, 24–31.

- Del Baldo, G.; Carta, R.; Alessi, I.; Merli, P.; Agolini, E.; Rinelli, M.; Boccuto, L.; Milano, G.M.; Serra, A.; Carai, A.; et al. Rhabdoid Tumor Predisposition Syndrome: From Clinical Suspicion to General Management. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 586288.

- Albert, C.M.; Davis, J.L.; Federman, N.; Casanova, M.; Laetsch, T.W. TRK Fusion Cancers in Children: A Clinical Review and Recommendations for Screening. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 37, 513–524.

- Bergoug, M.; Doudeau, M.; Godin, F.; Mosrin, C.; Vallée, B.; Bénédetti, H. Neurofibromin Structure, Functions and Regulation. Cells 2020, 9, 2365.

- Prudner, B.C.; Ball, T.; Rathore, R.; Hirbe, A.C. Diagnosis and Management of Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: Current Practice and Future Perspectives. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2020, 2, i40–i49.

- Zhu, Y.; Ghosh, P.; Charnay, P.; Burns, D.K.; Parada, L.F. Neurofibromas in NF1: Schwann Cell Origin and Role of Tumor Environment. Science 2002, 296, 920–922.

- De Raedt, T.; Beert, E.; Pasmant, E.; Luscan, A.; Brems, H.; Ortonne, N.; Helin, K.; Hornick, J.L.; Mautner, V.; Kehrer-Sawatzki, H.; et al. PRC2 Loss Amplifies Ras-Driven Transcription and Confers Sensitivity to BRD4-Based Therapies. Nature 2014, 514, 247–251.

- Röhrich, M.; Koelsche, C.; Schrimpf, D.; Capper, D.; Sahm, F.; Kratz, A.; Reuss, J.; Hovestadt, V.; Jones, D.T.W.; Bewerunge-Hudler, M.; et al. Methylation-Based Classification of Benign and Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 877–887.

- Reynolds, R.M.; Browning, G.G.P.; Nawroz, I.; Campbell, I.W. Von Recklinghausen’s Neurofibromatosis: Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Lancet 2003, 361, 1552–1554.

- Knight, T.; Shatara, M.; Carvalho, L.; Altinok, D.; Poulik, J.; Wang, Z.J. Dramatic response to trametinib in a male child with neurofibromatosis type 1 and refractory astrocytoma. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27474.

- Friedman, J.M. Neurofibromatosis 1. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Mirzaa, G., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington Seattle: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993.

- Shofty, B.; Constantini, S.; Ben-Shachar, S. Advances in Molecular Diagnosis of Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2015, 22, 234–239.

- Legius, E.; Messiaen, L.; Wolkenstein, P.; Pancza, P.; Avery, R.A.; Berman, Y.; Blakeley, J.; Babovic-Vuksanovic, D.; Soares Cunha, K.; Ferner, R.; et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 1 and Legius syndrome: An international consensus recommendation. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1506–1513.

- Malbari, F.; Spira, M.; Knight, P.B.; Zhu, C.; Roth, M.; Gill, J.; Abbott, R.; Levy, A.S. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors in Neurofibromatosis: Impact of Family History. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 40, e359–e363.

- Kluwe, L.; Friedrich, R.E.; Peiper, M.; Friedman, J.; Mautner, V.-F. Constitutional NF1 Mutations in Neurofibromatosis 1 Patients with Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors. Hum. Mutat. 2003, 22, 420.

- Nguyen, R.; Jett, K.; Harris, G.J.; Cai, W.; Friedman, J.M.; Mautner, V.-F. Benign Whole Body Tumor Volume Is a Risk Factor for Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2014, 116, 307–313.

- Valentin, T.; Le Cesne, A.; Coquard, R.I.; Italiano, A.; Decanter, G.; Bompas, E.; Isambert, N.; Thariat, J.; Linassier, C.; Bertucci, F.; et al. Management and Prognosis of Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: The Experience of the French Sarcoma Group (GSF-GETO). Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 56, 77–84.

- Miao, R.; Wang, H.; Jacobson, A.; Lietz, A.P.; Choy, E.; Raskin, K.A.; Schwab, J.H.; Deshpande, V.; Nielsen, G.P.; DeLaney, T.F.; et al. Radiation-Induced and Neurofibromatosis-Associated Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors (MPNST) Have Worse Outcomes than Sporadic MPNST. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 137, 61–70.

- Kolberg, M.; Høland, M.; Ågesen, T.H.; Brekke, H.R.; Liestøl, K.; Hall, K.S.; Mertens, F.; Picci, P.; Smeland, S.; Lothe, R.A. Survival Meta-Analyses for >1800 Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor Patients with and without Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Neuro-Oncology 2013, 15, 135–147.

- Cai, Z.; Tang, X.; Liang, H.; Yang, R.; Yan, T.; Guo, W. Prognosis and Risk Factors for Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 18, 257.

- Anghileri, M.; Miceli, R.; Fiore, M.; Mariani, L.; Ferrari, A.; Mussi, C.; Lozza, L.; Collini, P.; Olmi, P.; Casali, P.G.; et al. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: Prognostic Factors and Survival in a Series of Patients Treated at a Single Institution. Cancer 2006, 107, 1065–1074.

- Valeyrie-Allanore, L.; Ismaïli, N.; Bastuji-Garin, S.; Zeller, J.; Wechsler, J.; Revuz, J.; Wolkenstein, P. Symptoms Associated with Malignancy of Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumours: A Retrospective Study of 69 Patients with Neurofibromatosis 1. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005, 153, 79–82.

- Demehri, S.; Belzberg, A.; Blakeley, J.; Fayad, L.M. Conventional and Functional MR Imaging of Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: Initial Experience. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2014, 35, 1615–1620.

- Matsumine, A.; Kusuzaki, K.; Nakamura, T.; Nakazora, S.; Niimi, R.; Matsubara, T.; Uchida, K.; Murata, T.; Kudawara, I.; Ueda, T.; et al. Differentiation between Neurofibromas and Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors in Neurofibromatosis 1 Evaluated by MRI. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 135, 891–900.

- Well, L.; Salamon, J.; Kaul, M.G.; Farschtschi, S.; Herrmann, J.; Geier, K.I.; Hagel, C.; Bockhorn, M.; Bannas, P.; Adam, G.; et al. Differentiation of Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Using Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Neuro-Oncology 2019, 21, 508–516.

- Azizi, A.A.; Slavc, I.; Theisen, B.E.; Rausch, I.; Weber, M.; Happak, W.; Aszmann, O.; Hojreh, A.; Peyrl, A.; Amann, G.; et al. Monitoring of Plexiform Neurofibroma in Children and Adolescents with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 by FDG-PET Imaging. Is It of Value in Asymptomatic Patients? Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e26733.

- Berzaczy, D.; Mayerhoefer, M.E.; Azizi, A.A.; Haug, A.R.; Senn, D.; Beitzke, D.; Weber, M.; Traub-Weidinger, T. Does Elevated Glucose Metabolism Correlate with Higher Cell Density in Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Associated Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189093.

- Assadi, M.; Velez, E.; Najafi, M.H.; Matcuk, G.; Gholamrezanezhad, A. PET Imaging of Peripheral Nerve Tumors. PET Clin. 2019, 14, 81–89.

- Combemale, P.; Valeyrie-Allanore, L.; Giammarile, F.; Pinson, S.; Guillot, B.; Goulart, D.M.; Wolkenstein, P.; Blay, J.Y.; Mognetti, T. Utility of 18F-FDG PET with a Semi-Quantitative Index in the Detection of Sarcomatous Transformation in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85954.

- Le Guellec, S.; Decouvelaere, A.-V.; Filleron, T.; Valo, I.; Charon-Barra, C.; Robin, Y.-M.; Terrier, P.; Chevreau, C.; Coindre, J.-M. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor Is a Challenging Diagnosis: A Systematic Pathology Review, Immunohistochemistry, and Molecular Analysis in 160 Patients from the French Sarcoma Group Database. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 896–908.

- Kim, A.; Stewart, D.R.; Reilly, K.M.; Viskochil, D.; Miettinen, M.M.; Widemann, B.C. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors State of the Science: Leveraging Clinical and Biological Insights into Effective Therapies. Sarcoma 2017, 2017, 7429697.

- Graham, D.S.; Russell, T.A.; Eckardt, M.A.; Motamedi, K.; Seeger, L.L.; Singh, A.S.; Bernthal, N.M.; Kalbasi, A.; Dry, S.M.; Nelson, S.D.; et al. Oncologic Accuracy of Image-Guided Percutaneous Core-Needle Biopsy of Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors at a High-Volume Sarcoma Center. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 42, 739–743.

- Perez-Roman, R.J.; Shelby Burks, S.; Debs, L.; Cajigas, I.; Levi, A.D. The Risk of Peripheral Nerve Tumor Biopsy in Suspected Benign Etiologies. Neurosurgery 2020, 86, E326–E332.

More