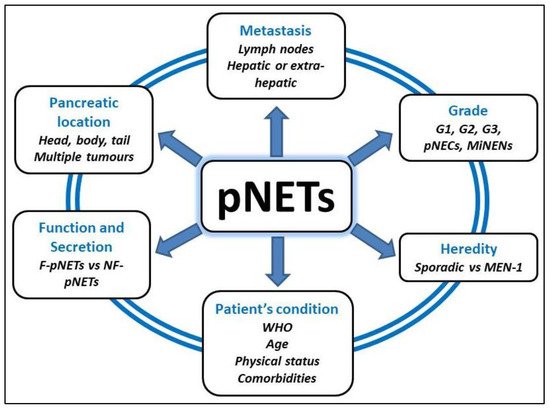

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNETs) are a group of rare neoplasms with an incidence of 1–2/100,000 inhabitants/year. They represent 2% of all pancreatic neoplasms and are characterized by a great heterogeneity according to their genetic or sporadic origin, their functional or non-functional character, their degree of locoregional or systemic invasion and their single or multiple localization. The reference curative treatment is surgical resection of the pancreatic tumor in specialized high-volume centres, after a multidisciplinary discussion involving surgeons, oncologists, radiologists and pathologists.

- pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours

- pancreatic neoplasm

- minimally invasive surgery

- MEN-1

1. Background

| Neoplasms (Secretion) |

Main Symptoms | Pancreatic Location |

|---|

| pNETs G3 | |||

| >20% | |||

| >20 | |||

| Poorly differentiated Pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas (pNECs) |

pNECs (G3) | >20% | >20 |

| Small cell type | |||

| Large cell type | |||

| Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNENs) | |||

2. Surgical Indications

2.1. When Surgery Might Not Be an Option?

-

Typical radiological features of low-grade pNET: marked arterial phase contrast on CT-scan or MRI, positive somatostatin receptor imaging, negative PET-FDG.

-

Histological proof of pNET well-differentiated G1, eventually expandable to G2 but with Ki67 < 5%.

-

No suspicion of lymph node or distant metastasis.

-

No pancreatic or biliary ductal dilatation on imaging.

-

No signs of radiological progression on follow-up.

| NF-pNETs (none) |

Depending on local invasion: asymptomatic (87%), jaundice, pancreatitis, pain, bleeding, digestive obstruction | 100% |

| Gastrinoma (Gastrin) |

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: Acid hypersecretion, peptic gastro-duodenal ulceration, diarrhea | 25% |

| Insulinoma (Insulin) |

Whipple’s triad (Symptomatic hypoglycaemia where restoration of normoglycaemia results in the disappearance of these symptoms), confusion, behavioral changes, visual troubles, coma | >99% |

| VIPoma (VIP) |

WDHA syndrome (watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, achlorhydria) | 90% |

| Glucagonoma (Glucagon) |

Necrotic migratory erythema, hyperglycemia, dilated cardiomyopathy, anemia, neuropsychiatric symptoms | 100% |

| Somatostatinoma (Somatostatin) | Diabetes mellitus, diarrhea, cholelithiases | 55% |

| pNENs | Ki-67 Proliferation Index | Mitotic Index (/2mm2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Well-differentiated Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNETs) |

pNETs G1 | <3% | <2 |

| pNETs G2 | 3–20% | 2–20 | |

2.2. When Surgery Is Required

2.2.1. NF-pNETs

2.2.2. F-pNETs

3. Where Patients with pNET Should Be Operated?

4. Intraoperative Strategy

4.1. Standard Pancreatectomy (SP) vs Parenchyma Sparing Pancreatectomy (PSP)

SP is a non-conservative surgery for pancreatic tumours. It includes pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for tumours located at the head of the pancreas, and the distal pancreatectomy (DP) for tumours usually on the left side of gastro-duodenal artery. Their advantages lie in the possibility of resecting the tumour with sufficient lateral margins, associated with formal lymphadenectomy. However, these are major surgeries, with a non-negligible risk of complications and which lead to an extensive resection of the pancreas, source of postoperative endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiencies

-

SP is a non-conservative surgery for pancreatic tumours. It includes pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for tumours located at the head of the pancreas, and the distal pancreatectomy (DP) for tumours usually on the left side of gastro-duodenal artery. Their advantages lie in the possibility of resecting the tumour with sufficient lateral margins, associated with formal lymphadenectomy. However, these are major surgeries, with a non-negligible risk of complications and which lead to an extensive resection of the pancreas, source of postoperative endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiencies

- .PSP is a conservative surgical treatment which includes the central pancreatectomy (CP) for tumours located on the isthmus, and enucleation that is indicated for superficial tumours far enough from the main pancreatic duct (2–3 mm of distance from it). From an oncological point of view, PSP only allows a limited resection in terms of margin around the tumour, without the possibility of performing a satisfactory lymph node removal. However, this surgery also presents a significant risk of postoperative complications, with a rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) sometimes even higher than SP. Nevertheless, due to the non-extensive resection, endocrine and exocrine pancreatic functions are preserved [28]. This is particularly important as a recent retrospective study found an association between postoperative diabetes mellitus exacerbation and increased risk of recurrence of pNET after pancreatectomy, in multivariable analysis (HR = 2.35)

[29] (Table 3).

-

(Table 3).Table 3. Elements to differentiate surgical procedures.

Standard Pancreatectomy (SP) Parenchyma Sparing Pancreatectomy (PSP) In general terms, when a surgery is indicated, SP is feasible in all situations. Nevertheless, PSP has to be preferred whenever it possible, in order to decrease endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiencies, taking into account the surgeon’s experience.Thus, the choice between these two categories of surgery will be based on three axes:-

The oncological objectives in terms of margins and especially lymph node dissection.

-

The tumour location.

-

The patient’s condition: age, comorbidities, curative anticoagulation, risk of pancreatic fistula, interest in preserving pancreatic function, etc.

Pancreatico-Duodenectomy

[30][31][32]Distal Pancreatectomy

[33][34]Central Pancreatectomy

[35][36]Enucleation

[37][38]Lymph nodes removal Yes Yes (RAMPS) ±No * No Mortality 2–5% <2% 0.4–1% 1% Overall morbidity 40–50% 30–50% 40–70% 50–60% CR-POPF

(grade B + C)10–20% 20–30% 25–35% 40% DGE 17% 6–20% 2% 5–15% New onset diabetes 16% 9–20% 4% <7% Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency 22–60% 10–30% 2% <5% CR-POPF: Clinically-relevant post-operative pancreatic fistula, grade B and C (ISGPS 2017). DGE: Delay Gastric Emptying; RAMPS: Radical antegrade modular pancreato-splenectomy. * A small lymph node dissection can be performed at least on the posterior side of the pancreas or if a resection of splenic vessels is done.4.1.1. NF-pNETs

Due to the good prognosis of small (<2 cm) asymptomatic NF-pNETs, if a “watch and wait” strategy is not chosen, PSP seems to be a good alternative with satisfactory oncological results [28][38][39]. In a multi-institutional retrospective review which compared enucleation and SP in 122 patients with pNET ≤ 3 cm and without nodal or metastatic disease, 5-year survival rate was similar [40]. However, since the risk of lymph node invasion in these tumours is 10%, lymph node picking seems a reasonable procedure. In all other cases, a SP remains recommended.4.1.2. Insulinoma

Sporadic insulinoma is a good prognosis tumour, often solitary with a small size [9][17][41]. PSP (notably enucleation) is an excellent indication, provided that the tumour has been correctly located, if needed with the use of intraoperative ultrasound [42].Malignant insulinoma are rare and frequently associated with larger and atypical tumours. Its treatment requires an extensive lymph nodes removal and a large parenchyma resection to obtain a R0 resection. A PSP is therefore not advisable in this case and a SP should be carried out.4.1.3. Gastrinoma

Gastrinomas may be unique or multiple and are often (more than 70% of cases) located in the duodenum. In fact, one of the most important elements in this disease is to locate the lesion(s). After extensive preoperative exploration, several methods are possible intraoperatively to localize associated lesions: duodenoscopy with transillumination and bi-digital palpation with duodenotomy for duodenal locations and ultrasound for pancreatic locations [43]. A study in 2004 demonstrates that routine use of duodenotomy in sporadic gastrinoma improved the rate of gastrinoma diagnosis from 76% to 98%, with an increase of short and long-term cure rate [44].Surgical resection associated with lymph nodes removal has been shown to increase overall survival in patients with sporadic gastrinoma [5][20][21]. Preferential location of gastrinoma is in an area so-called “Stabile and Passaro” triangle [45]. This area is bounded by the cystic duct on the top, the junction of the second and third duodenum on the right and the isthmus of the pancreas on the left. Thus, surgery could be either a PD or resection of the primary tumour by duodenectomy associated with a lymphadenectomy. In the past, if the gastrinoma was not found, a parietal cell vagotomy or total gastrectomy was performed. With the advent of PPIs, these procedures are no longer needed.Furthermore, patients with Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome (ZES) and a negative imaging should have surgical exploration by an experienced surgeon [5]. Indeed, a 2012 cohort study [46] reported that in these patients, gastrinoma was found intraoperatively in 98%, 46% were cured and the overall 20-year survival after resection was 71%. Conversely, as discussed in a previous paragraph, this rule only applies to sporadic gastrinomas as well as to gastrinomas in the context of MEN-1 but that do not meet the surveillance criteria as we will see in the paragraph on the MEN-1.4.1.4. Others F-pNETs

Concerning VIPoma, somatostatinomas and glucagonomas, all patients with localized tumours on preoperative imaging should undergo surgical exploration. However, these lesions present synchronous metastases more than half of cases at the diagnostic and the surgical management will depend on their resectability [47][48].4.2. Surgical Approach: Minimally Invasive or Open Pancreatectomy?

Today, minimally invasive surgery has become a standard of care for many procedures, reducing postoperative pain, length of stay, blood loss and complications without compromising oncological outcomes [49][50][51]. However, its diffusion in pancreatic surgery is slower due to the complexity and morbidity of the procedures. For now, there is no consensus concerning the indications of the minimally invasive approach for pancreatic resection in pNET [52].Laparoscopic approach in PD presents several inconveniences compared with open approach, including a long learning curve and a limited range of motion with poor surgeon ergonomics specially to perform anastomosis. Besides, no superiority or equivalence of the laparoscopic approach to the Whipple procedure has been demonstrated [53]. LEOPARD-2, a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing laparoscopic vs. open approach, was stopped prematurely due to an excess of mortality in the laparoscopic group (10% against 2%) [54]. The same results have been found in a practice evaluation among 7061 patients with a mortality rate of 5.1% vs. 3.1% in open approach [55]. Robotic surgery has several benefits obtained by three-dimensional vision and rotation in all planes of the instruments, compared with laparoscopic approach. These applications would be particularly interesting in PD with reconstruction and anastomosis times [56][57]. Nevertheless, laparoscopic or robotic PD could not be recommended at the present point.For DP, the laparoscopic approach is now widely practised. The literature, including two randomized controlled trials and their meta-analysis [58][59][60] suggests better short-term results for laparoscopy with fewer severe complications, fewer DGE, shorter length of stay, faster functional recovery, without additional costs. Long-term results, particularly in terms of oncology, are still awaited in these studies. The robot-assisted approach in DP seems less attractive due to the absence of reconstruction and the cost of robotic approach.For enucleation and central pancreatectomy, laparoscopy would appear from retrospective studies to have at least equivalent results to laparotomy [61][62].Thus, the minimal invasive approach has been progressively proposed for DP and PSP for pNETs. Various studies showed a benefice on short-term postoperative outcomes of a minimally invasive approach in the NF-pNETs and insulinoma without compromising oncologic results [58][63][64]. A meta-analysis on 907 patients demonstrated a shorter length of hospital stay for laparoscopy group compared with open approach in pancreatectomy for pNETs, without difference concerning others postoperative outcomes [65]. The robotic or laparoscopic approach seems to have the same postoperative results on DP for pNETs with perhaps less blood loss and more splenic preservation in the robot approach [34][66][67][68].The role of laparoscopy in gastrinoma surgery is controversial due to the necessity to explore the abdominal cavity to search multiple lesions which were not localized preoperatively, and notably the duodenum [69].4.3. The Practical Implications of a Biliary-Digestive Anastomosis in the Therapeutic Arsenal

NETs associated with liver metastasis are a major challenge. Surgery is the treatment of choice for resectable liver metastasis from well-differentiated NET with a 5-year survival rate of 60–80% [70][71]. However, for patients with unresectable liver metastasis, other therapies exist, led by liver transarterial embolization [72]. The latter includes selective internal radiation therapy and transarterial chemoembolization.Unfortunately, these techniques (excepted selective internal radiation therapy) are not recommended for patients with a biliary-digestive anastomosis (e.g., in PD), due to the high risk of sepsis and biliary ischaemia [72][73]. Indeed, a retrospective study of 397 transarterial chemoembolization showed that the risk of developing liver abscesses was increased with an odds ratio of 894, in patients with a biliary-digestive anastomosis [74].Thus, this consideration should be taken into account in patients undergoing PD for pNET where a biliary-digestive anastomosis will inevitably be performed. This will probably narrow of the scope of subsequent therapies in the case of hepatic metastatic disease.4.4. Cholecystectomy and NETs

SSAs are often the first line treatment for neuroendocrine disease. Unfortunately, several adverse events have been reported, mainly: gastrointestinal disturbances with pancreatic enzyme insufficiency (diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting), vitamin B12 deficiency, hyperglycaemia in 5%, and biliary gallstones [75]. Besides, in a large retrospective analysis of 478 patients treated with SSAs, biliary stone disease was observed in 27% of cases [76]. Biliary stones have been also reported in 10% of patients with lanreotide and 14% with octreotide in the CLARINET and PROMID trials, respectively [77][78]. In addition, several cases of ischaemic cholecystitis have been reported in the literature following chemoembolization [72]. Thus, prophylactic cholecystectomy during surgery for NET may be considered in this population at high risk of developing biliary pathology [79].4.5. Lymph Nodes Removal and NETs

Pancreatic NETs are frequently diagnosed with regional lymph nodes metastases. Moreover, the presence of positive lymph nodes and their number have important prognostic value and predictors of recurrence after pancreatectomy [80][81][82][83]. There is a consensus that if standard pancreatic resection is indicated, it should be associated with standardised lymph node dissection with a minimum number of 12–13 nodes resected [84][85]. Para-aortic lymph nodes removal in pNETs surgery does not seem to be recommended.5. Place of Surgery in Metastatic Disease?

Metastatic disease is common in pNETs. Indeed, approximately 50% of patients have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis [70]. Metastases are predominantly found in the liver (LM) [86] and lymph node. Extrahepatic metastatic disease, notably bone metastases that occur in 12% of cases [87], is a contraindication to surgery and has a poor prognosis [70]. In selected patients with synchronous bilobar LM, surgical resection can be performed in two stages to achieve complete resection of the primary tumour and LM with satisfactory long-term survival [88]. Of course, this extensive procedure is conditioned by the resectability of the LM and must be balanced against the almost inevitable risk of long-term metastatic recurrence.5.1. Resection of the Primary pNET in Patients with Liver Metastases

Despite the lack of prospective randomised controlled data in the literature to answer this question, several retrospective studies showed an improvement of survival rate after synchronous resection of primary pNET and resectable LM [71][89][90][91].In the setting of unresectable LM, there is no clear consensus on the place of resection of the primary pNET, even if it is avoided by most teams nowadays. The surgical indication, although rare, can be discussed in order to prevent possible local complications (portal hypertension, obstructive complications, hormonal refractory symptoms, etc.) or to anticipate a future liver transplantation. The most appropriate candidates may be those with a low-grade, very stable pNET located outside the head of the pancreas in order to avoid morbid surgery (PD) that would contraindicate subsequent locoregional liver treatments. Some retrospective studies suggest that resection of primary pNET in cases of unresectable metastases may be associated with a survival benefit [92][93]. A meta-analysis has been realized in 885 patients with pNET and unresectable LM. Among them, 252 underwent a surgical resection with a reduction of 5-year mortality rate (OR = 0.38) [93]. Lastly, an improvement in overall survival was also observed in patients who had destruction of LM by local ablative techniques such as thermal hepatic ablation, radiofrequency ablation or microwave ablation even if this remains also highly controversial [94].5.2. Surgery in Unresectable pNETs

Peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) affects 6–30% of gastro-entero-pancreatic NENs. Tumour reduction surgery may be proposed in selected patients. Some studies have shown an interest in performing a cytoreduction of peritoneal carcinomatosis in terms of survival when >90% of the disease could be resected [95][96][97]. In a retrospective study based on a National Cancer Data, the 5-year survival rate for patients with a metastatic disease who underwent surgical debulking, was 86% [98]. However, these are mainly studies of patients with small bowel NETs. Lastly, there is no evidence for the value of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in this indication [95]. Once again, this extensive resection has to be balanced against the almost inevitable risk of long-term metastatic recurrenc due to persistent microscopic tumours in all patients [99].6. What about Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (MEN-1)?

MEN-1 is an autosomal dominant hereditary syndrome with a prevalence of 2/100,000 inhabitants, caused by a mutation in the MEN-1 tumour suppressor gene on the long arm of chromosome 11 (11q13) [100][101]. The most common MEN-1 lesions (with their penetrance in parentheses) are: primary hyperparathyroidism (90%), Entero-pancreatic tumour (30–70%) with gastrinoma (40%), insulinoma (10%), NF-pNETs (20–55%), and others F-NETs (2%), anterior pituitary tumour adenoma (30–40%), adrenal cortical tumour (40%), thymic (2%) and bronchial carcinoid (2%), gastric enterochromaffin-like tumour (10%) [100][102]. The pNETs represent one of the principal causes of death in patients with MEN-1 [103]. Furthermore, the probability of diagnosing MEN-1 in patients with gastrinoma, insulinoma, VIPoma, glucagonoma and somatostatinoma are respectively 20%, 5%, 6%, 1–20% and 45% [3][4].Despite various published guidelines [4][104][105], the management of these tumours is difficult to standardize. Indeed, most if not all of patients with MEN-1 will have pNETs, knowing that in the vast majority of cases (not to say 100%) there are multiple with F-pNET and NF-pNET possibly co-existing in the same patient. [103].6.1. Gastrinoma

Approximately 40% of patients with MEN-1 syndrome have a gastrinoma whose primary location is duodenal. These are typically multifocal and small. Gastrinomas are associated with lymph node involvement in 40–60% of cases. Besides, other rarer intra-abdominal locations are described in the literature: pancreatic (rare and usually unique), extra-hepatic biliary tract and liver, stomach, mesentery, renal capsule, splenic hilum and omentum [106].Once again, a “wait and see” strategy is recommended for small gastrinoma (≤2 cm) in MEN-1 with no metastasis [107][108]. This option is all the more legitimate as typical gastrinoma in MEN-1 patients is preferentially multiple with an excellent survival rate of up to 90–100% at 15 years [5][109]. Gastric hypersecretion can be correctly controlled medically by PPI treatment [110]. However, the question arises as to the adverse effects induced by the long term use of high dose PPI [111], such as: enteric infections, microscopic colitis, chronic atrophic gastritis, malabsorption, kidney disease, etc. Histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2Ra) are an alternative to PPIs but with less clinical efficacy. Nevertheless, it would appear that H2Ra are associated with fewer long-term side effects than PPIs, although there is some contradiction in the literature [112][113]. Concerning the place of SSA in the management of gastrinomas, here again, they suffer from the rarity of their prevalence with little data in the literature, preventing us from defining a consensus. Several studies have already demonstrated the value of SSA in the management of NETs in terms of tumour control and disease free survival (CLARINET and PROMID). Although few gastrinomas have been included in these studies, we know the importance of somatostatin receptor expression in this tumour, which allows us to easily extrapolate the results of SSAs to gastrinomas. Moreover, Ramundo et al. confirmed the impact of SSA on 20 patients with early-stage MEN-1 related duodeno-pancreatic NETs, with a tumour response in 10% and a prolonged clinical and biochemical response in all patients [114]. Finally, several case series in the literature have demonstrated the benefit of SSA on gastrin level and symptoms of ZES. Nevertheless, PPIs remain the standard treatment due to their widely proven and long-lasting efficacy, as well as their oral availability [115].Surgery is indicated in the other cases and if there is a nodal involvement [116] due to the fact that 25% of gastrinoma tumours finally show an aggressive behaviour. Given that the preferential location of gastrinoma in MEN-1 is the duodenum, its exploration (by endoscopic transillumination or duodenotomy) should be performed intraoperatively. Management of MEN-1-associated gastrinoma higher than >2 cm is controversial most notably because of its duodenal location. Indeed, there is no clear consensus on the choice between limited resection with duodenotomy ± lymph node removal ± DP vs. PD. Theoretically, the first option allows resection of the tumour and prevention of metastatic progression, with less morbid surgery but without achieving long-term cure. The second option, i.e., PD, avoids the risk of duodenal recurrence, but at the expense of more morbid surgery, while the risk of developing F-pNETs on the remaining pancreas is still present. However, the reality is more complex. In a limited cohort of 22 patients with duodenal gastrinoma associated with MEN-1, even though disease–free survival rate was higher after PD than limited resection, there was no difference on overall survival [117]. Besides, in literature, biochemical cure rate, defined by negative secretin test, is higher after PD (between 77% and 100% in literature) than after limited resection (nearly 30%). On the opposite, several authors support the excellent functional and oncological results following surgery with limited resection and complete duodenal exploration [118][119][120]. In the future, better tumour staging and better prediction of the aggressiveness of gastrinomas in MEN-1 will be key elements in the choice of intervention.6.2. NF-pNETs

The prevalence of NF-pNETs in patients with MEN-1 is between 30–75%. Their management is similar to the sporadic NF- pNETs [107][108].6.3. Insulinoma

Approximately 10% of patients with MEN-1 have an insulinoma whereas 5% of patients with insulinoma have a MEN-1. Unlike sporadic insulinoma which are mostly isolated therefore eligible for enucleation, insulinomas in the context of MEN-1 are frequently multiple. Thus, two surgical approaches are possible: either multiple enucleations of the main tumours after a thorough search for all pancreatic tumour locations, or an enlarged DP associated with enucleation of possible lesions of the head of the pancreas. Besides, enucleation is associated with a higher rate of hypoglycaemia recurrence compared to DP, respectively 33% versus 8.7% [121][122]. The difficulty remains to preoperatively identify which ones of the multiple pNETs are secreting insulin.7. Surveillance

7.1. Survival Rate and Recurrence

Recurrence rate for pNETs resected is 12–25% at 5 years and up to 70% at 15 years [123][124][125][126]. Some authors have proposed scores to predict recurrence within 5 years after curative resection for patients with a G1 or G2 NF-pNET based on main recurrence risk factors, notably: positive lymph nodes, perineural invasion and tumour G2 [124][127]. Other nomograms have also been proposed to predict the risk of recurrence in patients who have had liver resection for LM from pNETs [128].For insulinoma, the risk of recurrence in patient with MEN-1 was 21% at 10 years against 5% at 10 years in patient with sporadic insulinoma [129]. Concerning patients with gastrinoma, 10-year survival rate was 30% with LM and 83% without LM [130]. The level of fasting serum gastrin (FSG) at the time of diagnosis may be useful in planning the extent of sporadic gastrinoma and to estimate prognosis [131]. For somatostatinoma, the 5-year postoperative survival rate is about 75%, but there is few data in the literature on this. The same applies to VIPoma and Glucagonoma.7.2. Follow-up of pNETs after Resection

Follow-up for patients who underwent a resection of pNETs, requires a careful monitoring with clinical exam, biological markers and radiological exam (CT-scan or MRI), every 6 months for pNETs G1 or G2 with Ki67 < 5%, and every 3 month for pNETs G2 with Ki67 > 5% [11]. This monitoring should continue over time, usually at least 10 years after pancreatectomy. Somatostatin receptor imaging should be repeated every 2 years if positive or earlier if progression is suspected [5].Surveillance interval might be adapted to the tumour aggressiveness with the aim of personalized medicine, reduction of extra costs and radiological irradiation. Indeed, a study of 1006 patients defined a recurrence risk score (RRS) for resected well/moderately differentiated NF-pNETs, based on the 4 risk factors predictive of recurrence found in multivariate analysis (symptomatic tumour, size > 2 cm, Ki67 > 20% and lymph nodes positivity). Patients were scored from 0–10 and divided into 3 groups according to the degree of risk. Based on this allocation, the authors propose an adjustment of oncological surveillance every 12-, 6-, 3-months for low-, moderate- and high-risk groups respectively [132].Some authors have also proposed the use of postoperative blood measurement of neuroendocrine gene transcripts (NETest) for early assessment of surgical resection of pNETs [133]. But its value as a marker of recurrence remains to be demonstrated, unlike the chromogranin A assay, which is recommended by NANETS for post-operative follow-up [134].8. Conclusions

The management of pNETs is complex and requires extensive medical and surgical coordination, which will be discussed at a dedicated multidisciplinary staff meeting in expert centres. The curative treatment of pNETs is largely based on surgery. The latter have to take into account many parameters: tumour characteristics, location, patient’s history, informed patient choice, etc. The consensus is that surgery should be performed routinely for NF-pNETs larger than 2 cm or for F-pNETs of any size. A “watch and wait” strategy can be proposed for asymptomatic NF-pNETs < 2 cm, as well as for gastrinomas less than 2 cm in the context of MEN-1. For pancreatic resection, the choice between a SP and a PSP is based on many elements, including tumour type, risk of lymph node invasion, patient’s history, subsequent use of chemoembolization, informed patient preference, etc. The laparoscopic minimally invasive approach is currently increasingly practised except for PD. Further trials, including prospective randomised trials, are needed to refine the selection and surgical management of patients with advanced or metastatic disease. -

References

- Dasari, A.; Shen, C.; Halperin, D.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, S.; Xu, Y.; Shih, T.; Yao, J.C. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1335–1342.

- Crona, J.; Norlén, O.; Antonodimitrakis, P.; Welin, S.; Stålberg, P.; Eriksson, B. Multiple and Secondary Hormone Secretion in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 445–452.

- Halfdanarson, T.R.; Rabe, K.G.; Rubin, J.; Petersen, G.M. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): Incidence, prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2008, 19, 1727–1733.

- Jensen, R.T.; Cadiot, G.; Brandi, M.L.; de Herder, W.W.; Kaltsas, G.; Komminoth, P.; Scoazec, J.-Y.; Salazar, R.; Sauvanet, A.; Kianmanesh, R.; et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: Functional pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes. Neuroendocrinology 2012, 95, 98–119.

- Falconi, M.; Eriksson, B.; Kaltsas, G.; Bartsch, D.K.; Capdevila, J.; Caplin, M.; Kos-Kudla, B.; Kwekkeboom, D.; Rindi, G.; Klöppel, G.; et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Patients with Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Non-Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2016, 103, 153–171.

- Gaujoux, S.; Partelli, S.; Maire, F.; D’Onofrio, M.; Larroque, B.; Tamburrino, D.; Sauvanet, A.; Falconi, M.; Ruszniewski, P. Observational study of natural history of small sporadic nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 4784–4789.

- Tsoli, M.; Chatzellis, E.; Koumarianou, A.; Kolomodi, D.; Kaltsas, G. Current best practice in the management of neuroendocrine tumors. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 10, 2042018818804698.

- Sallinen, V.; Le Large, T.Y.S.; Galeev, S.; Kovalenko, Z.; Tieftrunk, E.; Araujo, R.; Ceyhan, G.O.; Gaujoux, S. Surveillance strategy for small asymptomatic non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors—A systematic review and meta-analysis. HPb 2017, 19, 310–320.

- Crippa, S.; Partelli, S.; Zamboni, G.; Scarpa, A.; Tamburrino, D.; Bassi, C.; Pederzoli, P.; Falconi, M. Incidental diagnosis as prognostic factor in different tumor stages of nonfunctioning pancreatic endocrine tumors. Surgery 2014, 155, 145–153.

- Partelli, S.; Cirocchi, R.; Crippa, S.; Cardinali, L.; Fendrich, V.; Bartsch, D.K.; Falconi, M. Systematic review of active surveillance versus surgical management of asymptomatic small non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 34–41.

- Pavel, M.; Öberg, K.; Falconi, M.; Krenning, E.P.; Sundin, A.; Perren, A.; Berruti, A.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2020, 31, 844–860.

- Tanaka, M.; Heckler, M.; Mihaljevic, A.L.; Probst, P.; Klaiber, U.; Heger, U.; Schimmack, S.; Büchler, M.W.; Hackert, T. Systematic Review and Metaanalysis of Lymph Node Metastases of Resected Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1614–1624.

- Farges, O.; Bendersky, N.; Truant, S.; Delpero, J.R.; Pruvot, F.R.; Sauvanet, A. The Theory and Practice of Pancreatic Surgery in France. Ann. Surg. 2017, 266, 797–804.

- Fusai, G.K.; Tamburrino, D.; Partelli, S.; Lykoudis, P.; Pipan, P.; Di Salvo, F.; Beghdadi, N.; Dokmak, S.; Wiese, D.; Landoni, L.; et al. Portal vein resection during pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. An international multicenter comparative study. Surgery 2021, 169, 1093–1101.

- Partelli, S.; Bartsch, D.K.; Capdevila, J.; Chen, J.; Knigge, U.; Niederle, B.; Nieveen van Dijkum, E.J.M.; Pape, U.-F.; Pascher, A.; Ramage, J.; et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for Standard of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumours: Surgery for Small Intestinal and Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours. Neuroendocrinology 2017, 105, 255–265.

- Nikfarjam, M.; Warshaw, A.L.; Axelrod, L.; Deshpande, V.; Thayer, S.P.; Ferrone, C.R.; Fernández-del Castillo, C. Improved contemporary surgical management of insulinomas: A 25-year experience at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Ann. Surg. 2008, 247, 165–172.

- Mehrabi, A.; Fischer, L.; Hafezi, M.; Dirlewanger, A.; Grenacher, L.; Diener, M.K.; Fonouni, H.; Golriz, M.; Garoussi, C.; Fard, N.; et al. A systematic review of localization, surgical treatment options, and outcome of insulinoma. Pancreas 2014, 43, 675–686.

- Silva, F.A.O.B.; Colaiacovo, R.; Araki, O.; Domene, A.F.; Lima Junior, J.V.; de Moricz, A.; Rossini, L. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle injection of alcohol for ablation of an insulinoma: A well documented successful procedure. Endoscopy 2019, 51, E57–E58.

- Barthet, M.; Giovannini, M.; Lesavre, N.; Boustiere, C.; Napoleon, B.; Koch, S.; Gasmi, M.; Vanbiervliet, G.; Gonzalez, J.-M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and pancreatic cystic neoplasms: A prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy 2019, 51, 836–842.

- Bartsch, D.K.; Waldmann, J.; Fendrich, V.; Boninsegna, L.; Lopez, C.L.; Partelli, S.; Falconi, M. Impact of lymphadenectomy on survival after surgery for sporadic gastrinoma. Br. J. Surg. 2012, 99, 1234–1240.

- Norton, J.A.; Fraker, D.L.; Alexander, H.R.; Gibril, F.; Liewehr, D.J.; Venzon, D.J.; Jensen, R.T. Surgery increases survival in patients with gastrinoma. Ann. Surg. 2006, 244, 410–419.

- Hata, T.; Motoi, F.; Ishida, M.; Naitoh, T.; Katayose, Y.; Egawa, S.; Unno, M. Effect of Hospital Volume on Surgical Outcomes After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 2016, 263, 664–672.

- Gooiker, G.A.; van Gijn, W.; Wouters, M.W.J.M.; Post, P.N.; van de Velde, C.J.H.; Tollenaar, R.a.E.M. Signalling Committee Cancer of the Dutch Cancer Society Systematic review and meta-analysis of the volume-outcome relationship in pancreatic surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2011, 98, 485–494.

- Kaltsas, G.; Caplin, M.; Davies, P.; Ferone, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Grozinsky-Glasberg, S.; Hörsch, D.; Tiensuu Janson, E.; Kianmanesh, R.; Kos-Kudla, B.; et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Pre- and Perioperative Therapy in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2017, 105, 245–254.

- Howe, J.R.; Merchant, N.B.; Conrad, C.; Keutgen, X.M.; Hallet, J.; Drebin, J.A.; Minter, R.M.; Lairmore, T.C.; Tseng, J.F.; Zeh, H.J.; et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Consensus Paper on the Surgical Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas 2020, 49, 1–33.

- Beger, H.G.; Poch, B.; Mayer, B.; Siech, M. New Onset of Diabetes and Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency After Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Benign and Malignant Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Long-term Results. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 259–270.

- Falconi, M.; Mantovani, W.; Crippa, S.; Mascetta, G.; Salvia, R.; Pederzoli, P. Pancreatic insufficiency after different resections for benign tumours. Br. J. Surg. 2008, 95, 85–91.

- Cherif, R.; Gaujoux, S.; Couvelard, A.; Dokmak, S.; Vuillerme, M.-P.; Ruszniewski, P.; Belghiti, J.; Sauvanet, A. Parenchyma-sparing resections for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J. Gastrointest. Surg. Off. J. Soc. Surg. Aliment. Tract 2012, 16, 2045–2055.

- De Mestier, L.; Védie, A.-L.; Faron, M.; Cros, J.; Rebours, V.; Hentic, O.; Do Cao, C.; Bardet, P.; Lévy, P.; Sauvanet, A.; et al. The Postoperative Occurrence or Worsening of Diabetes Mellitus May Increase the Risk of Recurrence in Resected Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2020, 110, 967–976.

- Traverso, L.W.; Hashimoto, Y. Delayed gastric emptying: The state of the highest level of evidence. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. 2008, 15, 262–269.

- Lai, E.C.H.; Lau, S.H.Y.; Lau, W.Y. Measures to prevent pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy: A comprehensive review. Arch. Surg. Chic. Ill 1960 2009, 144, 1074–1080.

- Scholten, L.; Mungroop, T.H.; Haijtink, S.A.L.; Issa, Y.; van Rijssen, L.B.; Koerkamp, B.G.; van Eijck, C.H.; Busch, O.R.; DeVries, J.H.; Besselink, M.G. New-onset diabetes after pancreatoduodenectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery 2018, 164, 6–16.

- Ecker, B.L.; McMillan, M.T.; Allegrini, V.; Bassi, C.; Beane, J.D.; Beckman, R.M.; Behrman, S.W.; Dickson, E.J.; Callery, M.P.; Christein, J.D.; et al. Risk Factors and Mitigation Strategies for Pancreatic Fistula After Distal Pancreatectomy: Analysis of 2026 Resections From the International, Multi-institutional Distal Pancreatectomy Study Group. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 143–149.

- De Rooij, T.; van Hilst, J.; Vogel, J.A.; van Santvoort, H.C.; de Boer, M.T.; Boerma, D.; van den Boezem, P.B.; Bonsing, B.A.; Bosscha, K.; Coene, P.-P.; et al. Minimally invasive versus open distal pancreatectomy (LEOPARD): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 166.

- Iacono, C.; Verlato, G.; Ruzzenente, A.; Campagnaro, T.; Bacchelli, C.; Valdegamberi, A.; Bortolasi, L.; Guglielmi, A. Systematic review of central pancreatectomy and meta-analysis of central versus distal pancreatectomy. Br. J. Surg. 2013, 100, 873–885.

- Goudard, Y.; Gaujoux, S.; Dokmak, S.; Cros, J.; Couvelard, A.; Palazzo, M.; Ronot, M.; Vullierme, M.-P.; Ruszniewski, P.; Belghiti, J.; et al. Reappraisal of central pancreatectomy a 12-year single-center experience. JAMA Surg. 2014, 149, 356–363.

- Jilesen, A.P.J.; van Eijck, C.H.J.; Busch, O.R.C.; van Gulik, T.M.; Gouma, D.J.; van Dijkum, E.J.M.N. Postoperative Outcomes of Enucleation and Standard Resections in Patients with a Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. World J. Surg. 2016, 40, 715–728.

- Crippa, S.; Bassi, C.; Salvia, R.; Falconi, M.; Butturini, G.; Pederzoli, P. Enucleation of pancreatic neoplasms. Br. J. Surg. 2007, 94, 1254–1259.

- Casadei, R.; Ricci, C.; Rega, D.; D’Ambra, M.; Pezzilli, R.; Tomassetti, P.; Campana, D.; Nori, F.; Minni, F. Pancreatic endocrine tumors less than 4 cm in diameter: Resect or enucleate? a single-center experience. Pancreas 2010, 39, 825–828.

- Pitt, S.C.; Pitt, H.A.; Baker, M.S.; Christians, K.; Touzios, J.G.; Kiely, J.M.; Weber, S.M.; Wilson, S.D.; Howard, T.J.; Talamonti, M.S.; et al. Small pancreatic and periampullary neuroendocrine tumors: Resect or enucleate? J. Gastrointest. Surg. Off. J. Soc. Surg. Aliment. Tract 2009, 13, 1692–1698.

- Guo, Q.; Wu, Y. Surgical treatment of pancreatic islet cell tumor: Report of 44 cases. Hepatogastroenterology 2013, 60, 2099–2102.

- Placzkowski, K.A.; Vella, A.; Thompson, G.B.; Grant, C.S.; Reading, C.C.; Charboneau, J.W.; Andrews, J.C.; Lloyd, R.V.; Service, F.J. Secular trends in the presentation and management of functioning insulinoma at the Mayo Clinic, 1987–2007. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 1069–1073.

- Norton, J.A.; Cromack, D.T.; Shawker, T.H.; Doppman, J.L.; Comi, R.; Gorden, P.; Maton, P.N.; Gardner, J.D.; Jensen, R.T. Intraoperative ultrasonographic localization of islet cell tumors. A prospective comparison to palpation. Ann. Surg. 1988, 207, 160–168.

- Norton, J.A.; Alexander, H.R.; Fraker, D.L.; Venzon, D.J.; Gibril, F.; Jensen, R.T. Does the use of routine duodenotomy (DUODX) affect rate of cure, development of liver metastases, or survival in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome? Ann. Surg. 2004, 239, 617–625.

- Howard, T.J.; Stabile, B.E.; Zinner, M.J.; Chang, S.; Bhagavan, B.S.; Passaro, E. Anatomic distribution of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Am. J. Surg. 1990, 159, 258–264.

- Norton, J.A.; Fraker, D.L.; Alexander, H.R.; Jensen, R.T. Value of surgery in patients with negative imaging and sporadic Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann. Surg. 2012, 256, 509–517.

- Chu, Q.D.; Al-kasspooles, M.F.; Smith, J.L.; Nava, H.R.; Douglass, H.O.; Driscoll, D.; Gibbs, J.F. Is glucagonoma of the pancreas a curable disease? Int. J. Pancreatol. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Pancreatol. 2001, 29, 155–162.

- House, M.G.; Yeo, C.J.; Schulick, R.D. Periampullary pancreatic somatostatinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2002, 9, 869–874.

- Bonjer, H.J.; Deijen, C.L.; Haglind, E.; COLOR II Study Group A. Randomized Trial of Laparoscopic versus Open Surgery for Rectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 194.

- Van der Pas, M.H.; Haglind, E.; Cuesta, M.A.; Fürst, A.; Lacy, A.M.; Hop, W.C.; Bonjer, H.J. COlorectal cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection II (COLOR II) Study Group Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): Short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 210–218.

- Palanivelu, C.; Senthilnathan, P.; Sabnis, S.C.; Babu, N.S.; Srivatsan Gurumurthy, S.; Anand Vijai, N.; Nalankilli, V.P.; Praveen Raj, P.; Parthasarathy, R.; Rajapandian, S. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumours. Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 1443–1450.

- Asbun, H.J.; Moekotte, A.L.; Vissers, F.L.; Kunzler, F.; Cipriani, F.; Alseidi, A.; D’Angelica, M.I.; Balduzzi, A.; Bassi, C.; Björnsson, B.; et al. The Miami International Evidence-based Guidelines on Minimally Invasive Pancreas Resection. Ann. Surg. 2020, 271, 1–14.

- Nickel, F.; Haney, C.M.; Kowalewski, K.F.; Probst, P.; Limen, E.F.; Kalkum, E.; Diener, M.K.; Strobel, O.; Müller-Stich, B.P.; Hackert, T. Laparoscopic Versus Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann. Surg. 2020, 271, 54–66.

- Van Hilst, J.; de Rooij, T.; Bosscha, K.; Brinkman, D.J.; van Dieren, S.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.; Gerhards, M.F.; de Hingh, I.H.; Karsten, T.M.; Lips, D.J.; et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2): A multicentre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 199–207.

- Adam, M.A.; Choudhury, K.; Dinan, M.A.; Reed, S.D.; Scheri, R.P.; Blazer, D.G.; Roman, S.A.; Sosa, J.A. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Cancer: Practice Patterns and Short-term Outcomes Among 7061 Patients. Ann. Surg. 2015, 262, 372–377.

- Guerra, F.; Checcacci, P.; Vegni, A.; di Marino, M.; Annecchiarico, M.; Farsi, M.; Coratti, A. Surgical and oncological outcomes of our first 59 cases of robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy. J. Visc. Surg. 2019, 156, 185–190.

- Liu, R.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Z.-M.; Tan, X.-L.; Zhao, G.-D.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y. The surgical outcomes of robot-assisted laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy versus laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary neoplasms: A comparative study of a single center. Surg. Endosc. 2017, 31, 2380–2386.

- Björnsson, B.; Larsson, A.L.; Hjalmarsson, C.; Gasslander, T.; Sandström, P. Comparison of the duration of hospital stay after laparoscopic or open distal pancreatectomy: Randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, 1281–1288.

- De Rooij, T.; van Hilst, J.; van Santvoort, H.; Boerma, D.; van den Boezem, P.; Daams, F.; van Dam, R.; Dejong, C.; van Duyn, E.; Dijkgraaf, M.; et al. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy (LEOPARD): A Multicenter Patient-blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 2–9.

- Korrel, M.; Vissers, F.L.; van Hilst, J.; de Rooij, T.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.; Festen, S.; Groot Koerkamp, B.; Busch, O.R.; Luyer, M.D.; Sandström, P.; et al. Minimally invasive versus open distal pancreatectomy: An individual patient data meta-analysis of two randomized controlled trials. HPb 2021, 23, 323–330.

- Guerra, F.; Giuliani, G.; Bencini, L.; Bianchi, P.P.; Coratti, A. Minimally invasive versus open pancreatic enucleation. Systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical outcomes. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 1509–1516.

- Dokmak, S.; Ftériche, F.S.; Aussilhou, B.; Lévy, P.; Ruszniewski, P.; Cros, J.; Vullierme, M.P.; Khoy Ear, L.; Belghiti, J.; Sauvanet, A. The Largest European Single-Center Experience: 300 Laparoscopic Pancreatic Resections. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2017, 225, 226–234.e2.

- Sciuto, A.; Abete, R.; Reggio, S.; Pirozzi, F.; Settembre, A.; Corcione, F. Laparoscopic spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy for insulinoma: Experience of a single center. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2014, 12, S152–S155.

- Al-Kurd, A.; Chapchay, K.; Grozinsky-Glasberg, S.; Mazeh, H. Laparoscopic resection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 4908–4916.

- Tamburrino, D.; Partelli, S.; Renzi, C.; Crippa, S.; Muffatti, F.; Perali, C.; Parisi, A.; Randolph, J.; Fusai, G.K.; Cirocchi, R.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on laparoscopic pancreatic resections for neuroendocrine neoplasms (PNENs). Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 11, 65–73.

- Van Hilst, J.; de Rooij, T.; Klompmaker, S.; Rawashdeh, M.; Aleotti, F.; Al-Sarireh, B.; Alseidi, A.; Ateeb, Z.; Balzano, G.; Berrevoet, F.; et al. Minimally Invasive versus Open Distal Pancreatectomy for Ductal Adenocarcinoma (DIPLOMA): A Pan-European Propensity Score Matched Study. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 10–17.

- Casadei, R.; Ricci, C.; D’Ambra, M.; Marrano, N.; Alagna, V.; Rega, D.; Monari, F.; Minni, F. Laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy in pancreatic tumours: A case-control study. Updat. Surg. 2010, 62, 171–174.

- Zhang, J.; Jin, J.; Chen, S.; Gu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, K.; Zhan, Q.; Cheng, D.; Chen, H.; Deng, X.; et al. Minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy for PNETs: Laparoscopic or robotic approach? Oncotarget 2017, 8, 33872–33883.

- Ayav, A.; Bresler, L.; Brunaud, L.; Boissel, P.; SFCL (Société Française de Chirurgie Laparoscopique); AFCE (Association Francophone de Chirurgie Endocrinienne). Laparoscopic approach for solitary insulinoma: A multicentre study. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2005, 390, 134–140.

- Frilling, A.; Modlin, I.M.; Kidd, M.; Russell, C.; Breitenstein, S.; Salem, R.; Kwekkeboom, D.; Lau, W.; Klersy, C.; Vilgrain, V.; et al. Recommendations for management of patients with neuroendocrine liver metastases. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e8–e21.

- Pavel, M.; O’Toole, D.; Costa, F.; Capdevila, J.; Gross, D.; Kianmanesh, R.; Krenning, E.; Knigge, U.; Salazar, R.; Pape, U.-F.; et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Distant Metastatic Disease of Intestinal, Pancreatic, Bronchial Neuroendocrine Neoplasms (NEN) and NEN of Unknown Primary Site. Neuroendocrinology 2016, 103, 172–185.

- De Mestier, L.; Zappa, M.; Hentic, O.; Vilgrain, V.; Ruszniewski, P. Liver transarterial embolizations in metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 459–471.

- De Baere, T.; Deschamps, F.; Tselikas, L.; Ducreux, M.; Planchard, D.; Pearson, E.; Berdelou, A.; Leboulleux, S.; Elias, D.; Baudin, E. GEP-NETS update: Interventional radiology: Role in the treatment of liver metastases from GEP-NETs. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 172, R151–R166.

- Kim, W.; Clark, T.W.; Baum, R.A.; Soulen, M.C. Risk factors for liver abscess formation after hepatic chemoembolization. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. JVIR 2001, 12, 965–968.

- Grasso, L.F.S.; Auriemma, R.S.; Pivonello, R.; Colao, A. Adverse events associated with somatostatin analogs in acromegaly. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2015, 14, 1213–1226.

- Brighi, N.; Panzuto, F.; Modica, R.; Gelsomino, F.; Albertelli, M.; Pusceddu, S.; Massironi, S.; Lamberti, G.; Rinzivillo, M.; Faggiano, A.; et al. Biliary Stone Disease in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors Treated with Somatostatin Analogs: A Multicenter Study. Oncologist 2020, 25, 259–265.

- Rinke, A.; Müller, H.-H.; Schade-Brittinger, C.; Klose, K.-J.; Barth, P.; Wied, M.; Mayer, C.; Aminossadati, B.; Pape, U.-F.; Bläker, M.; et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors: A report from the PROMID Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4656–4663.

- Caplin, M.E.; Pavel, M.; Ćwikła, J.B.; Phan, A.T.; Raderer, M.; Sedláčková, E.; Cadiot, G.; Wolin, E.M.; Capdevila, J.; Wall, L.; et al. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 224–233.

- Pavel, M.; Valle, J.W.; Eriksson, B.; Rinke, A.; Caplin, M.; Chen, J.; Costa, F.; Falkerby, J.; Fazio, N.; Gorbounova, V.; et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Systemic Therapy-Biotherapy and Novel Targeted Agents. Neuroendocrinology 2017, 105, 266–280.

- Partelli, S.; Gaujoux, S.; Boninsegna, L.; Cherif, R.; Crippa, S.; Couvelard, A.; Scarpa, A.; Ruszniewski, P.; Sauvanet, A.; Falconi, M. Pattern and clinical predictors of lymph node involvement in nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NF-PanNETs). JAMA Surg. 2013, 148, 932–939.

- Boninsegna, L.; Panzuto, F.; Partelli, S.; Capelli, P.; Delle Fave, G.; Bettini, R.; Pederzoli, P.; Scarpa, A.; Falconi, M. Malignant pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour: Lymph node ratio and Ki67 are predictors of recurrence after curative resections. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 1990 2012, 48, 1608–1615.

- Hashim, Y.M.; Trinkaus, K.M.; Linehan, D.C.; Strasberg, S.S.; Fields, R.C.; Cao, D.; Hawkins, W.G. Regional lymphadenectomy is indicated in the surgical treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs). Ann. Surg. 2014, 259, 197–203.

- Han, X.; Xu, X.; Jin, D.; Wang, D.; Ji, Y.; Lou, W. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis-related factors of resectable pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A retrospective study of 104 cases in a single Chinese center. Pancreas 2014, 43, 526–531.

- Guarneri, G.; de Mestier, L.; Landoni, L.; Partelli, S.; Gaujoux, S.; Andreasi, V.; Nessi, C.; Dokmak, S.; Fontana, M.; Dousset, B.; et al. Prognostic Role of Examined and Positive Lymph Nodes after Distal Pancreatectomy for Non-Functioning Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology 2021, 111, 728–738.

- Partelli, S.; Javed, A.A.; Andreasi, V.; He, J.; Muffatti, F.; Weiss, M.J.; Sessa, F.; La Rosa, S.; Doglioni, C.; Zamboni, G.; et al. The number of positive nodes accurately predicts recurrence after pancreaticoduodenectomy for nonfunctioning neuroendocrine neoplasms. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Assoc. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 778–783.

- Riihimäki, M.; Hemminki, A.; Sundquist, K.; Sundquist, J.; Hemminki, K. The epidemiology of metastases in neuroendocrine tumors. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 2679–2686.

- Van Loon, K.; Zhang, L.; Keiser, J.; Carrasco, C.; Glass, K.; Ramirez, M.-T.; Bobiak, S.; Nakakura, E.K.; Venook, A.P.; Shah, M.H.; et al. Bone metastases and skeletal-related events from neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr. Connect. 2015, 4, 9–17.

- Kianmanesh, R.; Sauvanet, A.; Hentic, O.; Couvelard, A.; Lévy, P.; Vilgrain, V.; Ruszniewski, P.; Belghiti, J. Two-step surgery for synchronous bilobar liver metastases from digestive endocrine tumors: A safe approach for radical resection. Ann. Surg. 2008, 247, 659–665.

- Gaujoux, S.; Gonen, M.; Tang, L.; Klimstra, D.; Brennan, M.F.; D’Angelica, M.; Dematteo, R.; Allen, P.J.; Jarnagin, W.; Fong, Y. Synchronous resection of primary and liver metastases for neuroendocrine tumors. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 4270–4277.

- Birnbaum, D.J.; Turrini, O.; Vigano, L.; Russolillo, N.; Autret, A.; Moutardier, V.; Capussotti, L.; Le Treut, Y.-P.; Delpero, J.-R.; Hardwigsen, J. Surgical management of advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Short-term and long-term results from an international multi-institutional study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 1000–1007.

- Keutgen, X.M.; Nilubol, N.; Glanville, J.; Sadowski, S.M.; Liewehr, D.J.; Venzon, D.J.; Steinberg, S.M.; Kebebew, E. Resection of primary tumor site is associated with prolonged survival in metastatic nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery 2016, 159, 311–318.

- Bertani, E.; Fazio, N.; Botteri, E.; Chiappa, A.; Falconi, M.; Grana, C.; Bodei, L.; Papis, D.; Spada, F.; Bazolli, B.; et al. Resection of the primary pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor in patients with unresectable liver metastases: Possible indications for a multimodal approach. Surgery 2014, 155, 607–614.

- Partelli, S.; Cirocchi, R.; Rancoita, P.M.V.; Muffatti, F.; Andreasi, V.; Crippa, S.; Tamburrino, D.; Falconi, M. A Systematic review and meta-analysis on the role of palliative primary resection for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm with liver metastases. HPb 2018, 20, 197–203.

- Kjaer, J.; Stålberg, P.; Crona, J.; Welin, S.; Hellman, P.; Thornell, A.; Norlen, O. Long-term outcome after resection and thermal hepatic ablation of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour liver metastases. BJS Open 2021, 5, zrab062.

- De Mestier, L.; Lardière-Deguelte, S.; Brixi, H.; O’Toole, D.; Ruszniewski, P.; Cadiot, G.; Kianmanesh, R. Updating the surgical management of peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2015, 101, 105–111.

- Merola, E.; Prasad, V.; Pascher, A.; Pape, U.-F.; Arsenic, R.; Denecke, T.; Fehrenbach, U.; Wiedenmann, B.; Pavel, M.E. Peritoneal Carcinomatosis in Gastro-Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Clinical Impact and Effectiveness of the Available Therapeutic Options. Neuroendocrinology 2020, 110, 517–524.

- Kianmanesh, R.; Ruszniewski, P.; Rindi, G.; Kwekkeboom, D.; Pape, U.-F.; Kulke, M.; Sevilla Garcia, I.; Scoazec, J.-Y.; Nilsson, O.; Fazio, N.; et al. ENETS consensus guidelines for the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2010, 91, 333–340.

- Concors, S.J.; Sinnamon, A.J.; Ecker, B.L.; Metz, D.C.; Vollmer, C.M.; Fraker, D.L.; Roses, R.E. The impact of surgery for metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor: A contemporary evaluation matching for chromogranin a level. HPb 2020, 22, 83–90.

- Elias, D.; Lefevre, J.H.; Duvillard, P.; Goéré, D.; Dromain, C.; Dumont, F.; Baudin, E. Hepatic metastases from neuroendocrine tumors with a “thin slice” pathological examination: They are many more than you think. Ann. Surg. 2010, 251, 307–310.

- Thakker, R.V.; Newey, P.J.; Walls, G.V.; Bilezikian, J.; Dralle, H.; Ebeling, P.R.; Melmed, S.; Sakurai, A.; Tonelli, F.; Brandi, M.L.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 2990–3011.

- Al-Salameh, A.; Cadiot, G.; Calender, A.; Goudet, P.; Chanson, P. Clinical aspects of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 207–224.

- Santucci, N.; Gaujoux, S.; Binquet, C.; Reichling, C.; Lifante, J.-C.; Carnaille, B.; Pattou, F.; Mirallié, E.; Facy, O.; Mathonnet, M.; et al. Pancreatoduodenectomy for Neuroendocrine Tumors in Patients with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1: An AFCE (Association Francophone de Chirurgie Endocrinienne) and GTE (Groupe d’étude des Tumeurs Endocrines) Study. World J. Surg. 2021, 45, 1794–1802.

- Goudet, P.; Murat, A.; Binquet, C.; Cardot-Bauters, C.; Costa, A.; Ruszniewski, P.; Niccoli, P.; Ménégaux, F.; Chabrier, G.; Borson-Chazot, F.; et al. Risk factors and causes of death in MEN1 disease. A GTE (Groupe d’Etude des Tumeurs Endocrines) cohort study among 758 patients. World J. Surg. 2010, 34, 249–255.

- Newey, P.J.; Thakker, R.V. Role of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 mutational analysis in clinical practice. Endocr. Pract. Off. J. Am. Coll. Endocrinol. Am. Assoc. Clin. Endocrinol. 2011, 17, 8–17.

- Yates, C.J.; Newey, P.J.; Thakker, R.V. Challenges and controversies in management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours in patients with MEN1. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 895–905.

- Ito, T.; Igarashi, H.; Jensen, R.T. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: Recent advances and controversies. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 29, 650–661.

- Triponez, F.; Sadowski, S.M.; Pattou, F.; Cardot-Bauters, C.; Mirallié, E.; Le Bras, M.; Sebag, F.; Niccoli, P.; Deguelte, S.; Cadiot, G.; et al. Long-term Follow-up of MEN1 Patients Who Do Not Have Initial Surgery for Small ≤2 cm Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors, an AFCE and GTE Study: Association Francophone de Chirurgie Endocrinienne & Groupe d’Etude des Tumeurs Endocrines. Ann. Surg. 2018, 268, 158–164.

- Pieterman, C.R.C.; de Laat, J.M.; Twisk, J.W.R.; van Leeuwaarde, R.S.; de Herder, W.W.; Dreijerink, K.M.A.; Hermus, A.R.M.M.; Dekkers, O.M.; van der Horst-Schrivers, A.N.A.; Drent, M.L.; et al. Long-Term Natural Course of Small Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors in MEN1-Results From the Dutch MEN1 Study Group. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 3795–3805.

- Jensen, R.T.; Berna, M.J.; Bingham, D.B.; Norton, J.A. Inherited pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes: Advances in molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis, management, and controversies. Cancer 2008, 113, 1807–1843.

- Ito, T.; Igarashi, H.; Uehara, H.; Jensen, R.T. Pharmacotherapy of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2013, 14, 307–321.

- Eusebi, L.H.; Rabitti, S.; Artesiani, M.L.; Gelli, D.; Montagnani, M.; Zagari, R.M.; Bazzoli, F. Proton pump inhibitors: Risks of long-term use. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 1295–1302.

- January, S.E.; Progar, K.; Nesselhauf, N.M.; Hagopian, J.C.; Malone, A.F. Choice of Acid Suppressant Therapy and Long-Term Graft Outcomes After Kidney Transplantation. Pharmacotherapy 2020, 40, 1082–1088.

- Shin, G.-Y.; Park, J.M.; Hong, J.; Cho, Y.K.; Yim, H.W.; Choi, M.-G. Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors vs. Histamine 2 Receptor Antagonists for the Risk of Gastric Cancer: Population-Based Cohort Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 1211–1219.

- Ramundo, V.; Del Prete, M.; Marotta, V.; Marciello, F.; Camera, L.; Napolitano, V.; De Luca, L.; Circelli, L.; Colantuoni, V.; Di Sarno, A.; et al. Impact of long-acting octreotide in patients with early-stage MEN1-related duodeno-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2014, 80, 850–855.

- Guarnotta, V.; Martini, C.; Davì, M.V.; Pizza, G.; Colao, A.; Faggiano, A.; NIKE Group. The Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: Is there a role for somatostatin analogues in the treatment of the gastrinoma? Endocrine 2018, 60, 15–27.

- Vinault, S.; Mariet, A.-S.; Le Bras, M.; Mirallié, E.; Cardot-Bauters, C.; Pattou, F.; Ruszniewski, P.; Sauvanet, A.; Chanson, P.; Baudin, E.; et al. Metastatic Potential and Survival of Duodenal and Pancreatic Tumors in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1: A GTE and AFCE Cohort Study (Groupe d’étude des Tumeurs Endocrines and Association Francophone de Chirurgie Endocrinienne). Ann. Surg. 2020, 272, 1094–1101.

- Lopez, C.L.; Falconi, M.; Waldmann, J.; Boninsegna, L.; Fendrich, V.; Goretzki, P.K.; Langer, P.; Kann, P.H.; Partelli, S.; Bartsch, D.K. Partial pancreaticoduodenectomy can provide cure for duodenal gastrinoma associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 308–314.

- Thompson, N.W. Current concepts in the surgical management of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 pancreatic-duodenal disease. Results in the treatment of 40 patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, hypoglycaemia or both. J. Intern. Med. 1998, 243, 495–500.

- Mortellaro, V.E.; Hochwald, S.N.; McGuigan, J.E.; Copeland, E.M.; Vogel, S.B.; Grobmyer, S.R. Long-term results of a selective surgical approach to management of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome in patients with MEN-1. Am. Surg. 2009, 75, 730–733.

- Norton, J.A. Surgical treatment and prognosis of gastrinoma. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2005, 19, 799–805.

- Vezzosi, D.; Cardot-Bauters, C.; Bouscaren, N.; Lebras, M.; Bertholon-Grégoire, M.; Niccoli, P.; Levy-Bohbot, N.; Groussin, L.; Bouchard, P.; Tabarin, A.; et al. Long-term results of the surgical management of insulinoma patients with MEN1: A Groupe d’étude des Tumeurs Endocrines (GTE) retrospective study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 172, 309–319.

- Van Beek, D.J.; Nell, S.; Verkooijen, H.M.; Borel Rinkes, I.H.M.; Valk, G.D.; on behalf of the DutchMEN Study Group; Vriens, M.R.; International MEN1 Insulinoma Study Group. Surgery for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1-related insulinoma: Long-term outcomes in a large international cohort. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, 1489–1499.

- Sho, S.; Court, C.M.; Winograd, P.; Toste, P.A.; Pisegna, J.R.; Lewis, M.; Donahue, T.R.; Hines, O.J.; Reber, H.A.; Dawson, D.W.; et al. A Prognostic Scoring System for the Prediction of Metastatic Recurrence Following Curative Resection of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. J. Gastrointest. Surg. Off. J. Soc. Surg. Aliment. Tract 2019, 23, 1392–1400.

- Genç, C.G.; Jilesen, A.P.; Partelli, S.; Falconi, M.; Muffatti, F.; van Kemenade, F.J.; van Eeden, S.; Verheij, J.; van Dieren, S.; van Eijck, C.H.J.; et al. A New Scoring System to Predict Recurrent Disease in Grade 1 and 2 Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 1148–1154.

- Ausania, F.; Senra Del Rio, P.; Gomez-Bravo, M.A.; Martin-Perez, E.; Pérez-Daga, J.A.; Dorcaratto, D.; González-Nicolás, T.; Sanchez-Cabus, S.; Tardio-Baiges, A. Can we predict recurrence in WHO G1-G2 pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms? Results from a multi-institutional Spanish study. Pancreatol. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Pancreatol. IAP Al 2019, 19, 367–371.

- Marchegiani, G.; Landoni, L.; Andrianello, S.; Masini, G.; Cingarlini, S.; D’Onofrio, M.; De Robertis, R.; Davì, M.; Capelli, P.; Manfrin, E.; et al. Patterns of Recurrence after Resection for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Who, When, and Where? Neuroendocrinology 2019, 108, 161–171.

- Ricci, C.; Partelli, S.; Landoni, L.; Rinzivillo, M.; Ingaldi, C.; Andreasi, V.; Nessi, C.; Muffatti, F.; Fontana, M.; Tamburrino, D.; et al. Sporadic non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: Multicentre analysis. Br. J. Surg. 2021, 108, 811–816.

- Xiang, J.-X.; Zhang, X.-F.; Weiss, M.; Aldrighetti, L.; Poultsides, G.A.; Bauer, T.W.; Fields, R.C.; Maithel, S.K.; Marques, H.P.; Pawlik, T.M. Multi-institutional Development and External Validation of a Nomogram Predicting Recurrence After Curative Liver Resection for Neuroendocrine Liver Metastasis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 3717–3726.

- Service, F.J.; McMahon, M.M.; O’Brien, P.C.; Ballard, D.J. Functioning insulinoma--incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival of patients: A 60-year study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1991, 66, 711–719.

- Weber, H.C.; Venzon, D.J.; Lin, J.T.; Fishbein, V.A.; Orbuch, M.; Strader, D.B.; Gibril, F.; Metz, D.C.; Fraker, D.L.; Norton, J.A. Determinants of metastatic rate and survival in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: A prospective long-term study. Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 1637–1649.

- Berger, A.C.; Gibril, F.; Venzon, D.J.; Doppman, J.L.; Norton, J.A.; Bartlett, D.L.; Libutti, S.K.; Jensen, R.T.; Alexander, H.R. Prognostic value of initial fasting serum gastrin levels in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 3051–3057.

- Zaidi, M.Y.; Lopez-Aguiar, A.G.; Switchenko, J.M.; Lipscomb, J.; Andreasi, V.; Partelli, S.; Gamboa, A.C.; Lee, R.M.; Poultsides, G.A.; Dillhoff, M.; et al. A Novel Validated Recurrence Risk Score to Guide a Pragmatic Surveillance Strategy After Resection of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: An International Study of 1006 Patients. Ann. Surg. 2019, 270, 422–433.

- Partelli, S.; Andreasi, V.; Muffatti, F.; Schiavo Lena, M.; Falconi, M. Circulating Neuroendocrine Gene Transcripts (NETest): A Postoperative Strategy for Early Identification of the Efficacy of Radical Surgery for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 3928–3936.

- Kunz, P.L.; Reidy-Lagunes, D.; Anthony, L.B.; Bertino, E.M.; Brendtro, K.; Chan, J.A.; Chen, H.; Jensen, R.T.; Kim, M.K.; Klimstra, D.S.; et al. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas 2013, 42, 557–577.