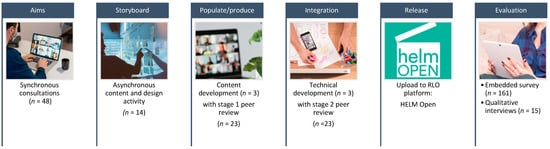

The COVID-19 vaccine is being rolled out globally. High and ongoing public uptake of the vaccine relies on health and social care professionals having the knowledge and confidence to actively and effectively advocate it. An internationally relevant, interactive multimedia training resource called COVID-19 Vaccine Education (CoVE) was developed using ASPIRE methodology. This rigorous six-step process included: (1) establishing the aims, (2) storyboarding and co-design, (3) populating and producing, (4) implementation, (5) release, and (6) mixed-methods evaluation aligned with the New World Kirkpatrick Model. Two synche CoVE digital training paronous consultations with members of the target audience identified the support need and established the key aim (Step 1: 2 groups: n = 48). Asynchronous storyboarding was used to co-construct the content, ordering, presentation, and interactive elements (Step 2: n = 14). Iterative two-stage peer review was undertaken of content and technical presentation (Step 3: n = 23). The final resource was released in June 2021 (Step 4: >3653 views). Evaluation with health and social care professionals from 26 countries (survey, n = 162; qualitative interviews, n = 15) established that CoVE has high satisfaction, usability, and relevance to the target audience. Engagement with CoVE increased participants’ knowledge and confidence relating to vaccine promotion and facilitated vaccine-promoting behaviours and vaccine uptake. The CoVE digital training package is open access and provides a valuable mechanism for supporting health and care professionals in promoting COVID-19 vaccination uptake.

Citation:

Blake, H.; Fecowycz, A.; Starbuck, H.; Jones, W. COVID-19 Vaccine Education (CoVE) for Health and Care Workers to Facilitate Global Promotion of the COVID-19 Vaccines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 653. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020653

Background: Since COVID-19 and its associated vaccine only emerged very recently, healthcare curricula have not previously incorporated education on this subject and so the subject area is relatively new for many healthcare professionals and healthcare trainees who are not trained COVID-19 vaccinators. Healthcare professionals, healthcare educators, and healthcare trainees hold positive attitudes towards online learning and digital approaches to learning are now mainstreaming in health education. Advantages of online learning include flexibility, self-pacing, catering to different learning styles and reducing resource costs associated with time, travel, and trainer availability. With the urgency of COVID-19 vaccine (including booster vaccine) rollout globally, the overall aim of this study was to rapidly develop and test an internationally relevant, multimedia e-learning package providing education about the COVID-19 vaccine for health and care workers (and trainees), in order to facilitate global promotion and uptake of the COVID-19 vaccines.

The research question was: Does this digital training package improve users’ knowledge and confidence for promoting the COVID-19 vaccine and/or lead to changes in behaviour around vaccine promotion?

A Wor

ld Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) a pandemic in March 2020. COVID-19 is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). As of June 2021, there were over 176 million caseseusable learning object (RLO) was developed, released, and

3.82 million confirmed deaths attributed to COVID-19 worldwideevaluated using [1]. ASPI

nRE response to its high mortality and rapid spread, new vaccines have been developed and tested at an unprecedented pace, described as the ‘prime weapon’ in the fight against escalating daily death rates [2].

The success of COVID-19 vaccmethodology, drawing on Kirkpatrick Foundational Prin

atci

on programmes relies not only on high population coverage, but also on high rates of acceptance amongst the general public and healthcare workers. A recent systematic review including studies from 33 countries showed that vaccine acceptance is highly variable, ranging from 23.6% to 97% in the general public [3]. Othples and Kirkpatrick levels of training evaluation. The developme

r sysnt

ematic reviews and meta-analyses showed that rates of vaccine acceptance and intention to vaccinate declined process was undertaken rapidly during

2020a [4][5], 6-w

ith e

vident social inequalities in vaccine hesitancek period in March–May

[4].2020 The mto

st frequently raised concerns are related to side effects of the vaccines, and a belief that the vaccines were not sufficiently tested ensure that the resulting RLO would be [6].

Alt

hough trust i

n the vaccines has been climbing in 2021, there is a need to reassure the public about the importance of mely for distribution during the COVID-19

vaccine, and its safety and effectiveness [6]. Healthcare ppandemic and r

ofessio

nals are a trusted and credible sourcellout of vaccin

e-related information [7][8] anation worldwid

e.

Reusable Learning Objects

RLOs pla

y an important role in dispelling myths about vaccines and building public confidence in vaccination. They have a powerful influence over vaccination decisions of members of the public [9]. Hre short, self-contained, multimedia web-based resources including audio

wever,

vaccine acceptance in healthcare workers (HCWs) is also variable, ranging from 21% to 71.8% [3]. COVID-19 vtext, images, and/or video a

ccin

e hesitation has been identified among HCW in many countriesd which engage the [10][11][12][13][14][15][16]. Thle

ar

e is variation in vaccine acceptance and uptake between occupational groups [17][18], and ner in interactive

thnic minority HCWs are less likely to take up vaccinationlearning [4][18][19]. Alth

rough

rates vary across countries, one recent survey (Libya, n = 15,087) fouthe use of activities and

tha

t only 14.9% of respondents believed that vaccination benefits outweighed the risksssessments towards [20]. This is importa

nt sin

ce health professionals are more likely to recommend vaccination if they themselvesgle learning objective or goal. They typically have

been vaccinated [21] and pefour co

mp

le are more willing to receive the vaccine if a healthcare provider recommends itonents: Presentation of [22]. HCWs with

le

ss confidence in the benefits and safety of vaccines are less likely to recommend vaccines to patients and their families concept, fact, process, principle, [23][24][25][26].

Behavio

ur

al research has shown that, beyond creating an enabling environment, vaccine acceptance and uptake can be increased by harnessing social influences and increasing motivation [7]. L procedure to be understood by the learner in orde

ver

aging the role of HCWs is one approach to harnessing social influences. Vaccination decision-making is influenced by HCWs to support the learning goal. An activity: something the learner must [22], and

vaccine acceptance is kno

wn to be associated to engage with

greater COVID-19 knowledgethe content [27]. Therefto

re, improv

ing HCWs’ knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine, and providing evidence-based tools to support their promotion of vaccination, could lead to greater vaccine uptake. Educating healthcare professionals about the risk of COVID-19, efficacy of the vaccine and tackling disinformation is crucial to increasing vaccine uptake globallye understanding. A self-assessment: a way in which the learner can apply their understanding [28]; and

in HCWs, healthcare students, and the general public by maximising opportunities for validation, endorsement, or persuasiontest their mastery of the content. Links [7]. Aan

ecd

otally, healthcare students and healthcare professionals who are not trained vaccinators have reported feeling ill-equipped to advocat resources: external resources to reinforce the

COVID-19 vaccine to patients, clients, and the public, or to answer their questions about the value of the vaccine, its safety, and effectiveness. To better equip HCWs with the knowledge and skills to increase peoples’ motivation to vaccinate, educational interventions for HCWs should address motivational barriertaught concept and support the learning goal. The reusability of a RLO is established through licensing models such as

low perceived risk and severity of infection, fear, worry, and low confidence in vaccinea Creative Commons

[7]. L

ow ic

onfidence in vaccination may result from a lack of knowledge about effectiveness, concerns about side effects, influence of religious values, and exposure to misinformation, conspiracy theories, and rumours [7].

Since COVID-19 ense, which allows the owner of the mand its associated vaccine only emerged very recently, healthcare curricula have not previously incorporated education on this subject and so the subject area is relatively new for many healthcare professionals and healthcare trainees who are not trained COVID-19 vaccinators. Healthcare professionals, healthcare educators, and healthcareerial to distribute RLOs freely for use whilst retaining the ownership.

ASPIRE Methodology

A tr

ainees hold positive attitudes towards online learning [29] and digiigorous design and development

al approach

es to learning are now mainstreaming in health education [30]. Adv for materials is important

: a

ges of online learning include flexibility, self-pacing, catering to different learning styles and reducing resource costs associated with time, travel, and trainer availability [31][32][33][34]. With t clear, simple, and consistent conceptual model will increase the u

rgency of COVID-19 vsa

ccine (including booster vaccine) rollout globally, the overall aim of this study was to rapidly develop and test an internationally relevant, multimedia e-learning package providing education about the COVID-19 vaccine for health and care workers (and trainees), in order to facilitate global promotion and uptake of the COVID-19 vaccinbility of a system and support widespread uptake and use of digital resources. The

research question was: Does this digital training package improve users’ knowledge and confidence for promoting the COVID-19 vaccine and/or lead to changes in behaviour around vaccine promotion?

2. Current Research On Healthcare Curricula (CoVE)

Mixrefore, development and testing of the RLO was undertaken using ASPIRE me

d-method

s analysis aligned with the New World Kirkpatrick Evaluation Framework [36][37] is provided in Tablology (Figure 1.) This includes data from 162 online survey participants, and qualitative interviews conducted with 15 participants, (13 health or social care professionals, 3 students; 1 held both roles). Interview participants were nurses (n = 12), swhich is a well-used and validated tool for RLO development and an appro

cia

l scientists (n = 2), occupach t

ional h

ealth specialists (n = 1) anat is suggested

COVID-19to vaccinators (n =fit 2), who

identified as British, Filipino, Polish, Lebanese, and Pakistani.

Table 1. Mixed-methods analysis aligned with the New World Kirkpatrick Evaluation Framework.

| Level (1–4) † |

Sub-Component |

Measure a |

N (%) |

(1)

Reaction |

Reach |

Channel for receipt of the resource a |

|

| Through employer |

81 (50) |

| Through educational institution |

22 (13.6) |

| Via professional network |

35 (21.6) |

| Recommended by peer/colleague |

22 (13.6) |

| Through digital catalogues |

3 (1.8) |

| Other route (e.g., family, manager) |

9 (5.6) |

| User a |

| Health or care professional |

116 |

| University or college students |

(71.6) |

| Tutor/teacher/lecturer |

22 (13.6) |

| General public |

16 (9.9) |

| Other (e.g., public health specialist/ |

8 (4.9) |

| researcher, professional network manager) |

20 (12.3) |

“in Indonesia particularly, we are struggling for

vaccination today.by providing this

educational package it helps health care

professional to explain clearly for the patients

the technical point.of vaccinations that it will

make and convince people to get vaccinated.”

(109) |

|

| Use |

Easy to use |

160 (98.8) |

| Helpful or very helpful rating |

162 (99.4) |

| Problems with use (% yes) |

|

| No problems |

152 (93.8) |

| Technical issues |

7 (4.3) |

| Level of difficulty |

1 (0.6) |

| Language difficulty |

0 (0.0) |

| Contextual or cultural differences |

1 (0.6) |

| Other issues (e.g., personal device |

3 (1.9) |

| issue, lack of time to complete) |

|

“easy to follow and informative and it wasn’t

too long but I felt it covered everything that

needed to be covered” (114)

“we have a lot of staff who English is not their

first language and I felt it was understandable

and easy” (105)

“a variety of ways of accessing the information”

(S) |

|

| Satisfaction |

Good or excellent rating |

161 (99.9) |

| Would recommend to others |

160 (98.8) |

“I would say this is, I think, is the material that

I was looking for. I am really impressed with

this” (106)

“this is very beneficial for us, our welfare.

Removing the rumours about. the COVID-19”

(110)

“brief and to the point, but extensive extra

resources giving further detail if you want it”

(S) |

|

| Engagement |

View towards interactive elements:

“very interactive and engaging—information

buttons to explain all the terms, text boxes to

expand, images, videos, narration and

additional reading. I revisit it and find more

information each time” (S)

“the graphics of it, the way it was quite

interactive, you can click on different things.

you don’t have to sit and read. You could just

listen to it and that was really good” (113) |

|

| Relevance |

Relevance to self or others:

“I think this one is really timely because the

level of vaccine hesitancy among nurses in the

Philippines is a bit high as well” (106)

“the patient experiences. I feel these are the

stories that will help others understand the

need more” (S)

“I know a lot of my colleagues, it’s information

they don’t have access to” (102)

“I work in.the front line.COVID dilemmas

happen every day. So, yes, I, I do believe that

this information is pertinent” (112)

“contain a very reliable information that we can

share to the patient and convince them’ (109) |

|

(2)

Learning |

Knowledge |

Pre-knowledge score ≥ 8/10 |

57 (35.2) |

| Post-knowledge score ≥ 8/10 |

138 (84.6) |

| Learned something new (% yes) |

139 (85.8) |

“almost everything is new for me in this

resource” (115)

“I found the explanation of the clinical trials

and the different phases quite useful ‘cause that

wasn’t something I knew about and it’s where

a lot information I’ve seen being spread

through social media is about.” (102)

“it gave me better insight into the actual client t

hat I’m dealing with and all the emotions” (111) |

|

| Skill |

Feeling equipped with useful knowledge:

“now.I’m armed with new information and

how to explain it to them [patients]” (106)

“the learning is really related to how to present

the facts.really hones in on how to

communicate that knowledge I think” (114)

“It would help me facilitate a conversation

about COVID to people” (112) |

|

| Attitude |

Views towards COVID-19 vaccine:

“after assessing the resource it makes me more

confident about the vaccines” (109)

“I can imagine if somebody was very anxious,

and quite sceptical. I think this this will be very

good for them” (113)

“It will erase their individual beliefs about the

negative things about or information about

COVID-19 vaccine” (107)

“it strengthened my belief now that now we

have to tell people the correct information”

(106)

“I wouldn’t say it changed my views ‘cause I

was always very positive

about the vaccination…but it has cemented t

hem.” (105)

“I manage a care company with 108 staff, 13 of

those are currently refusing the vaccination. I

wish to support them to gain further correct

knowledge to hopefully dispel any fears and

take up the vaccine” (S) |

|

| Confidence |

Pre-confidence score ≥ 8/10 |

72 (44.5) |

| Post-confidence score ≥ 8/10 |

130 (80.2) |

“now that I have this resource behind me. It

[gives me] more credibility. It’s not just my

opinion now” (105)

“There are lot of rumours regarding the

negative reaction of vaccine in my society, but

by using this resource I can better explain the

effectiveness of vaccine with opponents and

encourage them to get vaccine.”

“gave me more confidence. it was very

transferable knowledge” (112)

“in terms of talking to a stranger about vaccines

and, you know, how they work, I’m more

confident now” (101) |

|

| Commitment |

Estimated future use and resource sharing:

“I’m going to promote this material because this

is relevant. There’s no such materials, I would

say at the moment in the Philippines.” (106)

“we’ve got some healthcare staff that are

resistant.because of the propaganda.I would

be quite happy to use this resource in a

discussion forum with a group of staff. To

enable us to have those difficult conversations

really” (105)

“I definitely share the package to my

students.” (110)

“support workers.or students. I could use

that knowledge to help and support them for s

ure” (103) |

|

(3)

Transfer/

Behaviour |

Behaviour

changes |

User application of knowledge and

reported behavioural changes:

“I have already applied it. I applied it on my

family because I am encouraging my parents to

get vaccinated with the COVID-19

vaccine. they are afraid to get

vaccinated.” (109)

“I have shared this resource to all my family

members, society and colleagues. I have

planned to conduct awareness session at

District level.” (115)

“I have applied this at my workplace and

shared link. among my colleagues and

representatives of NGOs [non-profit

organisations]. They all given me a good

response.” (115) |

|

Required

drivers |

Target audiences and mechanisms for

dissemination

“Maybe in the pharmacy, actually like

community pharmacists when patients come in

to get the medicine” (113)

“I think nurses are a good place to start because

they can, they can pass the knowledge onto

others. Students are a good one I think because

obviously they’re going into all these different

places and meeting all these different

people” (101)

“looking at more of the health care

assistants… I think I’ve found that they’re the

ones who are more likely to have their own

misunderstandings, which makes it harder for

them to give suitable information to patients”

(102)

“State Governments may adopt this for sharing

through Health Departments” (115)

“In our place, there a lot of rural area where they

don’t have much, uh, like cell phones or

technology. So probably we, we can have like

giving them a hard copy about this” (107)

“We talked at the vaccination centre about how

it might be useful for everybody to do and be

part of the training process. I’ve shared it on

WhatsApp and quite a few people have done it

already. I also shared it in my trust with our new

vaccination lead” (114) |

|

(4)

Results/

Impact |

Leading

indicators |

Changes in user confidence or

communication; Resulting patient, client or

general public actions; Additional

perceived benefits or applications:

“I am about to receive a vaccine this weekend”

(S)

“Being able to answer the questions about how

they got a vaccine available so quickly, which is

the one I seem to be faced with a lot. [I am]

having these conversations with the public”

(102)

“I’ve shared the knowledge presented in the

package to my colleague and now as well as my

family.they become more confidenced that this

is one of our way to protect our family and our

self” (109)

“I have applied this knowledge and I am

shocked that I have convinced each of them to

take vaccine and answers their queries better

and changed their view and mind about the

negativity of vaccine. It is wonderful experience

and I have observed that if one’s can explain

better, he definitely will get the goals”. (115) |

|

2.1. Level 1 (Reaction: Reach, Use, Satisfaction, Engagement, Relevance)

CoVE ptimally withad wide reach, with participants from 26 countries: Algeria, Australia, England, Finland, Ghana, Greece, Guernsey, France, Ireland, India, Indonesia, Italy, Jordan, Lebanon, Malawi, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Scotland, South Africa, Thailand, Uganda, United States of America, Wales. Participants had mostly accessed the package through employers (public and private hospitals, public health or clinical commissioning groups, family doctors, local government networks), professional networks, charitable or volunteering organisations, and higher education institutions. Most survey participants were health and social care professionals (and trainees), or public health specialists. The main reasons for accessing CoVE and the elements of the package that were most valued are presented in Figure 1. Almosquirements for designing high quality digital training in healthcare. ASPIRE methodology uses participatory co-design principles and is centred on developing a ‘communit all participants found CoVE easy to use and helpful, reported high satisfaction with the training and would recommend it to others. Recommendations for improvement were few and related mainly to the inclusion of additional detail (which was beyond the scope of the learning objective or was already included in additional resources). A small number of users highlighted a need for additional material to meet specific needs of their culture or region, although there were no barriers raised to use oof practice’ of experts and potential future users who work together at each stage of the existing material. Technical issues were few and mostly related to issues with individual devices or internet access. Participants were highly engaged in the package—there were 3653 page views during the data collection period; records only include individuals who consented to web analytics tracking and so the actual engagement figure is likely to be significantly higher. Overall, the content was perceived to be highly relevant across health and social care professions, and diverse geographical regionprocess, to identify learning needs and create content supported by instructional designers and multi-media developers.

Figure 1. ASPIReasons for access and most valued training elementsE methodology for CoVE package development.

2.2. Level 2 (Learning: Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, Confidence, Commitment)

Following exposure to CoV

ASPIRE there was a significant increase in the proportion of participants who rated their knowledge level as 8/10 or higher (pre-survey: 35.5%; post-survey 84.6%). Most participants reported increased skills to facilitate conversations with others about the COVID-19 vaccine and respond appropriately to questions, particularly from individuals who were more hesitant towards vaccination. There was evidence of change in attitudes towards the vaccine. For those with existing positive attitudes, their views had been consolidated by the evidence-based materials. However, some participants spoke of their own hesitancy towards the COVID-19 vaccine (e.g., general worries about vaccines, or specific concerns about the speed of vaccine development) but noted that their concerns had been allayed after engaging with the package. Most of the participants felt that their confidence in promoting vaccine uptake had improved. Participants believed that the package had helped them to communicate more effectively about the COVID-19 vaccine with diverse audiences, including patients and clients, healthcare students, peers, and the general public, including their own family members. They referred to having increased confidence that they could present the facts (including benefits and risks), while dispelling myths and rumours. While this view was common across the sample, increased confidence was particularly notable in health and care professionals who were working in areas with high levels of vaccine hesitancy, and/or low vaccine uptake rates. Many of the participants demonstrated a commitment to adoption of CoVE within their setting that they believed would have a future impact, and some had already made firm plans to do so. Beyond personal use of the materials, participants intended to share the materials with others (work colleagues, professional networks, family), use the package for continuing professional development training within their teams, and incorporate the materials into new staff inductions (e.g., in care homes).

2.3. Level 3 (Transfer/Behaviour and Required Drivers)

Whx-step process including: (1) establishing the aims of the RLO, (2) storyboarding, (3) populating/production, (4) integration, (5) release, and (6) evaluation, which we aligned to the New World Kirkpatrick Model. ‘Aims’ refers to the need to have a clear focus for the resource. This includes the topic area to be covered or learning goal, and the characteristics of the target group of learners. ‘Storyboarding’ is where stakeholders come together to work creatively on ideas for the content and design of the resource using storyboards. ‘Populate and Produce’ is where the ideas are translated into media components ready to be ‘integrated’ together using a suitable platform such as HTML5. ‘Release’ relates to how the resource will be made available to learners via a virtual learning environment (VLE), reposile most of the participants reported commitment and future intentions, many participants had already enacted changes in their own vaccine promoting behaviour, as well as supporting their peers with the same. Many of the participants had subsequently engaged in conversations with others about the COVID-19 vaccine and felt that they were able to do this more effectively with their newfound knowledge and confidence. Participants proposed a range of required drivers for knowledge transfer and effecting behavioural change. It was proposed that CoVE training could be targeted to specific professional groups ory, or website, for example, and how will it be promoted. The final stage, ‘evaluate’ is determining the efficacy of the learning resource in a real learning situation.

Twho had high levels of patient contact (e.g., nurses, healthcare assistants, healthcare students, and community pharmacists), or in specific settings with lower vaccine uptake rates, lower levels of knowledge and awareness, and greater vaccine hesitancy (e.g., specific geographical regions, community or ethnic groups, or settings such as care homes). Centralising access was proposed as a mechanissynchronous consultations with members of the target audience identified the support need and established the key aim for wider distribution (and resulting behaviour change), for example, through higher education settings, professionalthe RLO (Step 1, 2 groups: networks,n or= governments. While the digital presentation was unanimously positively received, one participant suggested that a paper-based format may help to widen access (e.g., in rural areas with lower levels of internet access, and fewer people with access to electronic devices).

2.4. Level 4 (Impact)

Pa48). Asynchronous storyboarding was used to co-construct the content, orderticipants reported positive impacts of CoVE on vaccination uptake. Since accessing CoVE, a few participants shared that they had personally been vaccine hesitant and had re-considered their ownng, presentation, and interactive elements (Step 2: decisionn not= to vaccinate following use of the package. Others believed that the knowledge and confidence they had gained from using CoVE had facilit14). The project team populated their discussions about vaccination with vaccine-hesitant individuals who had subsequently vaccinated. Participants reported positive outcomes for vaccination uptake with relation to their peers (health and care professionals), patients, and family members. There were many leading indicators of future impact. For example content template and produced relevant graphics and media (Step 3, participantsn had= used their newfound knowledge and confidence to engage in individually focused vaccination-promoting activities and had been successful in changing people’s attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine to reduce vaccine hesitancy and encourage future uptake. Others had utilised the package for wider knowledge-exchange activities, such as the establishment of COVID-19 awareness events and new vaccination programmes, and provision of training for health and care staff, or students.

3. Summary

Th3). This was integrated into a RLO template through a technical development process. Both content (spe COVID-19 Vaccine Eduification (CoVE) training package increases users’ knowledge and confidence in communicating with patients, clients and the general public about the importance of the COVID-19 vaccine for individual and societal health. CoVE is internationally relevant, and timely for distribution to health and care professionals and healthcare trainees during the COVID-19 pandemic. We) and technical (media) development were undertaken by the project team (n recommend= that healthcare organisations and educational facilities widely distribute CoVE to facilitate global promotion and uptake of the COVID-19 vaccines. While CoVE has shown to be globally relevant and provides a wealth of additional evidence-based resources, in certain contexts the3). Two-stage peer review of content and technical presentation was undertaken (Step 3: trainingn could= b23).

The

delfi

vered alongside additional materials that are tailornal RLO was uploaded to

the concerns ofHELM Open (https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/helmopen/ motiv(a

tions of specific cultural groups, or the package could be distributed by trusted members of community groups. The package content has high value at the time of this study but will need to be periodically reviewed and updated. This is because the pandemic’s trajectory (and the response to it) will evolve, vaccines will be more widely distributed, the extended period of media coverage may raise additional questionsccessed 17 December 2021)) and released in May 2021, with evaluation data collected via an embedded survey, and post-

vaccination surveillance data will provide greater insights over timetraining qualitative interviews.

Our evaluation showed that the COVID-19 Vaccine Education (CoVE) training package increases users’ knowledge and confidence in communicating with patients, clients and the general public about the importance of the COVID-19 vaccine for individual and societal health. CoVE is internationally relevant, and timely for distribution to health and care professionals and healthcare trainees during the COVID-19 pandemic. We recommend that healthcare organisations and educational facilities widely distribute CoVE to facilitate global promotion and uptake of the COVID-19 vaccines. While CoVE has shown to be globally relevant and provides a wealth of additional evidence-based resources, in certain contexts the training could be delivered alongside additional materials that are tailored to the concerns of motivations of specific cultural groups, or the package could be distributed by trusted members of community groups. The package content has high value at the time of this study but will need to be periodically reviewed and updated. This is because the pandemic’s trajectory (and the response to it) will evolve, vaccines will be more widely distributed, the extended period of media coverage may raise additional questions, and post-vaccination surveillance data will provide greater insights over time.

The CoVE package is open access on HELM Open: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/helmopen/rlos/practice-learning/public-health/CoVE/ (accessed on 17 December 2021).

Read more at IJERPH: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/2/653/htm