Morocco is impacted by indigenous Berber, Arab, African, and European influences , and is often referred to as Al Maghreb (Arabic meaning "West"). The kingdom, which is the region's only monarchy and is located on North Africa's western edge, has managed to transform its rich cultural heritage into a tolerant state.

- Morocco

- cultural heritage

- historical monuments

- UNESCO

1. Defining "Heritage"

Heritage can be described in many ways, including tangibles such as sites, structures, and landscapes, or intangibles such as memories, sentiments, beliefs, and rituals, as well as how they are used in different cultures and nations. Heritage is typically associated with a traditional historical discourse, although it has recently expanded to include peripheral appearances, frequently emerging from people on the periphery of that discourse. Heritage is important for number of reasons, including cultural, political, and entrepreneurial reasons, as well as informative and emancipatory purposes. The use of the history by modern civilization is termed as cultural heritage. Our customs are a modern reflection of historical events that forms our national/cultural stereotypes and local identity[1].

Moshenska[2], in their study inspired from David Lowenthal's landmark book “The Past is a Foreign Country (1985)”, practice social science methods to examine the connections between people and their culture. Cultural heritage is “that part of the past which we select in the present for contemporary purposes, be they economic, cultural, political, or social”[3]. UNESCO defines cultural heritage as “the legacy of physical artifacts and intangible attributes of a group or society that are inherited from past generations, maintained in the present and bestowed for the benefit of future generations”[4].

2. The value of cultural heritage

Global cultural legacy is a representation of humanity's immense collective achievements throughout history. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) World Heritage program started out as an international mechanism in response to concerns that vital spaces and sites with outstanding universal qualities were deteriorating and eventually vanishing as a result of our modern society's rapid advancement[5]. The study of the economics and values of cultural heritage possesses a rich past[6][7][8][9]. According to Torre[10], "the cultural heritage (research) sector was rather isolated and mostly composed of small groups of specialists and experts who established what constituted cultural heritage and how it should be protected." The term "cultural heritage" refers to a variety of heritage types and has a variety of definitions[11]. UNESCO classifies the word "cultural heritage" into several categories. It can be studied from a variety of viewpoints (e.g., cultural, creative, archaeological, artistic, architectural, ethnological, religious, administrative, socio-economic, and historic), and also can be represented in various cognitive states (e.g., experiences, emotions, and appreciation). These cases demonstrate the worth that it offers. There is no common understanding or vocabulary among academics and professionals when it comes to the term "value" for cultural assets.

2.1 Tourism and cultural heritage

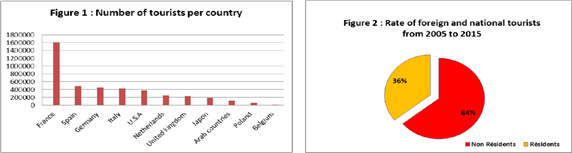

Tourism has played a pivotal role in the expansion of such ideas, owing to the fact that it is frequently considered as a prospective cause of quick economic expansion and one of a region's progress[12][13]. Notably, abundant research[14][15][16] has focused on the negative impacts of tourism on landscape quality, environmental conditions, and culture. Cultural inheritance and tourism are intertwined[17][18]. According to a study, travelers’ decision-making is influenced by their cultural background[19][20]. Cultural inheritance is acknowledged as a valued advantage for residents and visitors to a particular location. Many countries' national and municipal governments spent a lot of time and money to preserve and promote their cultural heritage. Cultural heritage can be viewed as a principal capital mode from an economic standpoint[21]. This cultural capital perspective could be viewed as a potential economic asset for a country (Ashworth & Voogd, 1986). The tourist industry heavily relies on visitors' enjoyment of these ancient cultural artifacts in terms of inventive, historical, ethical, cultural, and expressive worth. The emphasis on tourism primarily targets visits to historical sites. The monetary value created by such visits, as well as the resulting public recognition and appreciation, are critical to the tourist industry and the local economy[22]. Although academics and policymakers understand the broader economic benefits of cultural heritage, there are few quantitative studies that focus on cultural asset assessment from a tourism perspective.

Source: Investigation 2015

Thus, it seeks to attract tourists interested in historical sites as well as a variety of cultural events (fairs, conferences, and so on) that are likely to increase the rate of return. As an exhibitor, it must assemble the conditions that confer a tourist attraction capacity based on its historical significance and reputation as a cultural and spiritual metropolis.

3. Moroccan Cultural Heritage and Development

Over 15,000 sites and historic monuments have been identified in Morocco. Out of the approximately 17,000 known prehistoric rock-art sites, it has classed 243 as being of high importance. Due to a lack of resources, governments are unable to grant for new monuments and sites the “classified” status and ensuing protection. This also limits their capacity to profit from many a great monuments' economic potential. The MENA region has an extensive and rich oral cultural past in addition to its written and built heritages. The enormous souk in Old Sana'a, Yemen, and Djemaa el Fnaa Square in Marrakesh, Morocco, are remarkable illustrations of active cultural heritage sites. They are also valuable in terms of money to the craftsmen and local business owners who make handcrafted goods, set up food stalls and souvenir shops, as well as organize musical and dramatic events. This value and irreplaceability lead us to study their development potential in the most basic terms. The preservation of this worldwide archive is an aspect of people's cultural heterogeneity, or the protection of both commonality and variety without sacrificing one for the other[23].

Traditional living arts and crafts, on the other hand, are economically significant as a major business in which millions of people work across small businesses and micro workshops to make a livelihood. In Morocco, for example, the artisanal subsector employs over 2 million people. They make up roughly 12% of Morocco's working people and contribute close to 10% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). In Fez, for example, research suggests that 60% of the city's 5,800 artisanal units are comparatively novel, having been recognized in the 1980s and 1990s, defying many pessimistic forecasts handicraft enterprises[24]. Carpets account for around 33% of Moroccan artisanal exports, while ceramics accounts for about 20%. Producers of traditional carpets and kilims in Muslim-majority nations both preserve and expand the history by incorporating constant changes in terms of design and technique[25].

4. Morocco Culture, Customs, and Traditions

Morocco is a country with a rich culture and civilization. Throughout Moroccan history, it has hosted many people coming from East (Phoenicians, Jews, and Arabs), South (Sub-Saharan Africans), and North (Romans, Andalusians). All those civilizations have affected the social structure of Morocco. Numerous nations’ culture left their impact on the overall country’s culture. Moroccan culture is very diverse. In spite of its varied ethnicity and culture, the country has succeeded sustainability. Culturally speaking, Morocco has always been successful in combining its Berber, Jewish and Arabic cultural heritage with external influences such as the French and the Spanish and, during the last decades, the Anglo-American lifestyles.

4.1 Overview of Moroccan traditions and Culture

Morocco's culture is inspired by Berbers, Africans, Arabs, and Jews, and is a combination of ethnic origins and religions. It has also been able to highlight its customs while concurrently rising modernism, allowing the country to display itself more visibly on the international stage. Most of the population is made up of Berbers and Arabs, with Amazigh speakers accounting nearly 30% of the population. The influence of Berbers can be seen in a variety of Moroccan doings and lifestyles. The spices used are largely Berber in origin, while the cuisine varies from region to region. Fresh fruits and vegetables are commonly consumed due to the country's closeness to the Mediterranean. Its music features a wide range of traditional instruments, most of which are Arab or Amazigh in basis. It is the home of Andalusian traditional music, famous all over North Africa.

4.1.1 A vibrant culture

The medinas (ancient urban centers) are the ideal place to visit if you want to immerse yourself in Moroccan culture and traditions. Observe the hidden intricacies of Moroccan daily life as you meander through the alleyways of each medina. Morocco is known for its amicable gatherings as a Mediterranean country: from a cool tea ceremony to a delectable Couscous, the staple of solidarity, to a vibrant folklore event, you'll return home with incredible experiences to report and share.

4.1.2 Moroccan hospitality

Morocco's exceptional multiculturalism is reflected in its people, including Berbers, Arabs, Andalusians, Muslims, and Jews. Each neighborhood, like any other cosmopolitan location, features its own unique customs, although there are many common ethnicities. Moroccans are known for their hospitality, which is one of the common threads that binds them together. Tourists to the country of spectacular sunsets will discover that the art of greeting visitors is an important aspect of local culture. This hospitality, generally delivered with sincerity, takes on many forms, ranging from an invitation to try a renowned cup of tea, to a visit to a destination planned spontaneously around a delicious family dinner. Refusing an invitation can be viewed as disrespectful because hospitality is so essential. Accepting these charming gestures boosts your prospects of meeting new people and knowing more about a nation.

4.1.3 Multiculturalism contributes to a country’s reputation

Morocco has capitalized on its heterogeneity to promote itself as a global creative center. It is now well-known in the worlds of fashion, movie, and music, among many others. This is further evidenced by the Marrakech Folk Arts Festival, Marrakech International Film Festival, and Mawazine-Rhythms of the World Festival, among other notable traditional events hosted each year. Due to the cultural contrasts between the West and Maghreb, there is a need to know more about the essential living instructions that must be followed while one is there.

4.1.4 Languages and Religion

Morocco's population is primarily made up of Berbers and Arabs; the main languages are Berber and Arabic. French is extensively spoken across the country, apart from the northern part where Spanish is the primary language. In popular tourist sites such as Marrakech and other northern cities, English is widely spoken. Islam is the most widely practiced religion in the country. People place a high emphasis on family unity, and families are expected to look after each other. As a result, Morocco has a less number of senior apartments. Islam is a state religion, with the Sunni Muslim faction accounting for the vast majority of Muslims. Christianity is Morocco's second-largest religious group. Immigrants, on the other hand, consist of mainly Christians. Judaism and the Baha'i faith are two other religions that account for around 7% of its population.

4.1.5 Traditional Moroccan Clothing

The djellaba is a full sleeve, long hooded robe worn by both men and women in Morocco. Depending on the weather, a qob on the hood shields the user from the sun or the cold. Men wear bernouse or a red cap, usually referred to as a fez, while women wear kaftan on special events. The djellaba of women is bright in colors, and the kaftans are adorned with jewels. Most of the men's djellaba are plain and neutral in color. The kaftan, which is made up of many layers called takshita, is a symbol of elegance and sophistication. For casual wear, it's a versatile garment that can be dressed up or down. Moroccan teenagers are rapidly abandoning traditional clothing in favor of western clothes.

4.1.6 Moroccan Food

Moroccan food is well made and refined. The most significant feature of its preparation is the skill to cook with spices. The food is frequently a combination of Andalusian, Arabic, and Mediterranean cuisine with some European influences. Mediterranean fruits and vegetables, as well as meat, which serves as the cuisine's base, are among the food constituents. Cumin, oregano, caraway, and mint are all common spices. 27 different spices are used to make the Ras El Hanout spice. Couscous, a crushed durum wheat semolina dish, is the most popular Moroccan food. The most popular red meats are beef and lamb. Pastilla, harira, and tanjia are other popular foods. Morocco's mint green tea is the most popular beverage. Also, sharing this special mint tea with family and friends is a common practice all over the country.

4.1.7 Moroccan Art

Moroccan sculpture is inspired by suburb nations and cultures. The Berbers and Arabs, on the other hand, are credited with creating exceptional arts in the country. The iconic crimson Kasbahs fortress, which was occupied by the dominant class, is an example of their architecture. The crafts include colorful carpets and engraved gates with unique designs. Traditional Berber art and Islamic influence have also influenced current Moroccan art. The Zellij, which first flourished in the 14th century, is one of the most remarkable Islamic tile mosaics. A portrayal of riches and class, Zellij was used to embellish many houses.

5. UNESCO World Heritage sites

More UNESCO World Heritage sites are found in Morocco than in any other African country. Morocco has nine listed monuments, two more than ancient Egypt's wonder-strewn land, and another 13 places are up for review for inclusion on the UNESCO List[26].

ROMAN RUINS

5.1 Volubilis

The Roman ruins of Volubilis, which stem from the third century BC, are Morocco's best preserved archaeological monument. It was founded by the native Berber people before being built by the Romans and is thought to have been the center of the kingdom of Mauretania. The city had a basilica and a temple during its peak of prosperity, but after the Romans lost hold on Volubilis, it became an Islamic colony. Volubilis had been abandoned by the 11th century. The ruins of Volubilis were first excavated in the late 1800s, revealing several well-preserved antiquities. Beautiful mosaics were discovered, and the site was meticulously repaired.

IMPERIAL CITY

5.2 Meknes

Meknes , the lesser-visited city of Morocco's four grand towns, is an exceptional case of Moroccan architecture and urban design influenced by both Spanish and Moorish influences. The city was created by a Berber tribe and succeeded as a metropolis under Sultan Moulay Ismael, who erected the city's 25-kilometer-long walls in the 17th century. Non-Muslim guests are welcome to view the sultan's opulent mausoleum, which features vividly colored courtyards and ornately adorned interiors. Meknes is only a short distance from Fes, yet due to its nearness to one of Morocco's most well-known places, it is sometimes disregarded by travelers . El-Hedim square, a large square in Meknes' medina, with spectacular everyday life protests comparable to Marrakech's Djemaa el-Fnaa. The stately city gate, which is embellished with mosaics and inscriptions, leads to it.

FILM STAR KSAR

5.3 Aït Ben Haddou

Aït Ben Haddou is a red mudbrick structure that is one of Morocco's finest tourist attractions. It is the country's best-known and best-preserved icon. The medieval houses known as kasbahs, home to only a few hundred residents, are encircled by tall defensive walls with commanding corner towers. The remarkable clay architecture of it ages back to the 17th century, but it is Aït Ben Haddou’s more modern-day embodiments that appeal to foreign visitors. Most of the people have moved across the river into modern residences, and it is this void that lends Aït Ben Haddou its atmosphere of unidentified enchantment.

COASTAL FORTIFIED TOWN

5.4 Essaouira

For its remarkable medina and European military architecture, the walled town of Essaouira, situated on Morocco's west coast and fronting the Atlantic Ocean, was proclaimed a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001. In the late 18th century, Essaouira was developed as a tactical harbor, with its location picked for its proximity to Marrakech. A beautifully maintained medina with navigable lanes filled with colorful shops and fragrant markets is encircled by medieval-looking battlements. The Sqala du Port, located beyond the walls, overlooks a fishing harbor that has remained largely intact over time. The pleasure of visiting Essaouira is lies in its leisurely strolling, shopping, and tranquil ambiance.

ANCIENT LABYRINTH

5.5 Fez

Fez, Morocco's most ancient and stunning capital, captivates travelers from all over the planet. It's an enticing blend of values, art, and history, having served as a diverse community of Berbers, Muslims from Spain and Portugal, and Arabs. The city was established in the 9th century and flourished between the 13th and 14th centuries. The UNESCO-listed medina contains many palaces, madrasas (Islamic colleges), mosques, and houses from this time. The medina's primary layout has remained mostly unchanged over the millennia, and it is still the same befuddling network of lanes dotted with expanding market booths.

STREET THEATER

5.6 Marrakesh

Marrakesh, the most prominent of Morocco's royal cities and the starting point for the bulk of our Morocco itineraries, was a powerful trading center during the 16th century's political, economic, and cultural apex. The ancient city that you see today was founded in 1062 AD and is known for its terracotta-colored mudbrick walls and architecture, earning it the nickname "Red City". Since the 1960s, the city has seen numerous transitions, from monarchy capital has attracted visitors. In 1985, the medina of Marrakesh was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List for its extraordinary collection of antiquities.

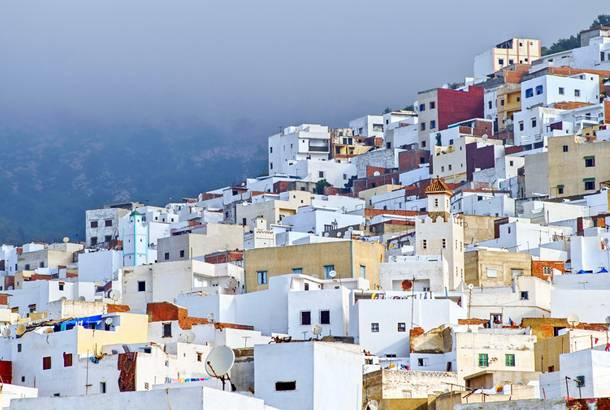

WHITE-WASHED MEDINA

5.7 Tétouan

The beautiful city of Tétouan, located between the Rif Mountains and the Mediterranean Sea, is a one-of-a-kind and ideal manifestation of Andalusian impact and Hispano-Moorish appeal. Tétouan was historically the principal idea of interaction between Andalusia and Morocco, home to Andalusian immigrants who influenced the city's art and architecture. Tétouan's medina was nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997, despite being unaffected by other cultural influences and remaining mostly unaffected by mass tourism. While the Tétouan medina is one of Morocco's smallest, it is well-kept and has a generally appealing legitimacy. The widespread avenues are free from traffic and chaos, however there's still a sense of the unusual, with local artists at work and stalls stacked high with locally grown goods.

PORTUGUESE FORTIFICATION

5.8 El Jadida

The UNESCO World Heritage Sites of this Portuguese city, once known as Mazagan, date from the 16th century and include an evocative medina, towering stone walls, and steep ramparts. The city, two hours south of Casablanca on the Atlantic coast, vividly displays the effects of European and Moroccan cultures, as well as how they were frequently integrated in urban town planning and architecture. The Old Portuguese city is small enough to see in a few hours, with wandering streets that maintain their mediaeval feel and a range of important structures such as the Grand Mosque, the abandoned synagogue, and the Church of the Assumption.

HISTORIC CAPITAL

5.9 Rabat

Rabat, Morocco's political and bureaucratic capital since the nation's independence from France in 1956, is a remarkable mix of the contemporary and the archaic. The city was established in the 12th century and became the capital of the state after an Almohad monarch built a citadel, making it newer than other mediaeval Moroccan cities. Rabat saw a rebirth during the French colonization in the early 1900s, when it was reinstalled as the capital following a long decline and loss to Fes. The Ville Nouvelle (French new town) is currently a spectacular example of 20th-century North African urban growth, along with intriguing remnants of Rabat before the French intervened. The city includes multiple arts and monuments such as the17th-century medina and the Hassan tower, which are the only completed parts of the project to build world’s largest mosque.

MAP SHOWING MOROCCO'S NINE UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITES

6. The Sustainability of Urban Heritage Preservation

With 31 medinas stretching back to medieval times and thousands of historic local rural villages strewn throughout its landscapes, Morocco has a huge and diverse urban cultural past. Given that the "modern" urban settlements, primarily constructed by the French Protectorate around the turn of the 20th century, were the exclusive domain of European residents, these medinas, ksours, and villages served as the exclusive residence for many of the 11.6 million Moroccans in 1960.

For many artists and writers, they have served as a source of ethnic inspiration, and their ambiance, vivid atmosphere, and rich architectural textures serve as the visual backdrop for all the images of Moroccan holiday tours that are attracting increasing numbers of foreign visitors to the country. However, due to their touristic appeal as well as increased governmental and private investments, some of these old cities have recently shown signs of economic resurgence. The protection of Morocco's medinas is a significant problem due to such contradictions, requirements, and potential. The preservation and promotion of cultural historic sites, both tangible and intangible, currently homes in on both local communities and tourists around the world. Because historical or cultural remnants are essentially the work of their communities, these are actively involved in their promotion and preservation.

According to the 2003 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Intangible Heritage, communities, groups of individuals, particularly artisans or locals, play a vital role in the security, maintenance, practice, and reproduction of intangible cultural heritage, contributing to cultural diversity and human creativity. As a result, we must improve management capability for human resource development to achieve long-term success.

The purpose of human resource development is to produce a group of experts who have a comprehensive understanding of the Cultural Heritage Law and related relevant formalities to protect and promote the value of historical-cultural treasures and landscapes. Because they are directly involved in the restoration and promotion processes, the local dwelling population at the heritage site or landscape must also be informed. They should be taught not just technical details about how to conserve the past, but also skills related to preservation and promotion, such as tour guide skills, experience tourism skills, and so on. The following are signs that Morocco is on the right track.

6.1 Source of Growth and Development

While Morocco’s cultural tradition is a source of national pride, it is undervalued and possesses untapped growth potential. The joint Program for Youth Entrepreneurship launched in 2021 has the goal to promote Morocco's cultural heritage and the position of creative industries in government policies and initiatives for human development, poverty reduction, and gender parity. The program intends to strike a balance between preserving Morocco's cultural heritage and utilizing it for economic development, in addition to supporting local socio-economic development and sustainability.

Morocco is a tourist hotspot, both domestically and internationally. It attracts a considerable number of international visitors and exemplifies Morocco's charm in every manner. Morocco has turned into a favorite tourist destination for many European visitors since adopting an open sky policy about 10 years ago. The city is merely a short flight away from all of Europe's major cities. As a result, the country’s wealth has been significantly impacted.

6.2 Increasing Attractiveness

Morocco is a popular tourist destination for people from the south and sub-Saharan Africa, and its status as an exclusive tourist destination has grown over time. Many factors, including an open-sky policy, a growth in tourism and second homes, the establishment of a municipal investment and urban facilities program, and the construction of a new university, have led to the city's remarkable boom beginning in the mid-1990s. Morocco's vibrant culture, which includes traditional arts and crafts, has spawned a thriving industry that employs millions of people.

6.3 Economic changes

In the southern oasis region, the benefits of cultural heritage in economic and social development have been discovered and included in national policy and municipal development plans. Until the 1990s, Morocco did not entice a lot of visitors. Agriculture, handicrafts, and the public sector were the economy's pillars. The economy has grown significantly and is now somewhat diversified, due to this rapid expansion of the tourist industry and both local and foreign investment in the residential sector beginning in the mid-1990s. Crafts, tourism, agri-food, and commerce, particularly crafts, tourism, services, and commerce, have all made significant contributions to the region's economic prosperity.

7. Conclusion

Our forefathers' legacy of historical and cultural relics, valued landscapes, and intangible cultural heritage is not only a huge and precious asset but also a resource for long-term growth. The cultural worth of these heritages is growing in importance as the globe becomes more globalized, expressing the spirit and knowledge of an entire country. If it is developed irresponsibly, this magnificent asset could be destroyed and forgotten. Furthermore, it may have a direct adverse impact on the environment as well as the nation’s socio-economic development by large. It is well acknowledged that when people attempt to endorse local heritage without adequate legislation and professional assistance, they risk damaging the place and potentially degrading the cultural heritage's qualities.

As a result, teamwork between government authorities and the local community is critical when dealing with cultural monuments and heritages.

References

- S. Boyd, “Cultural and heritage tourism in Canada: Opportunities, principles and challenges,” Herit. Tour. Exp. Crit. Essays, Vol. Two, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 9–31, 2003

- G. Moshenska, “Reply to comments from John Carman and Nils Anfinset: Expanding the Debate,” Nor. Archaeol. Rev., vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 181–182, 2009

- S. Khakzad, M. Pieters, and K. Van Balen, “Coastal cultural heritage: A resource to be included in integrated coastal zone management,” Ocean Coast. Manag., vol. 118, pp. 110–128, 2015.

- UNESCO, “UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage Convention,” E-international Relations, 2019.

- M. Houdek, “When Heritage Preservation Meets Living Memory: Constructing the Medina of Fez as a World Heritage Heterotopia,” p. 146, 2011

- H. Ashworth, G. J., & Voogd, “The marketing of urban heritage as an economic resource. Planning Without a Passport,” Utrecht, 1986.

- N. Z. S. L.N. Safiullin, I.R. Gafurov, R.N. Shaidullin, “Socio-economic development of the region and its historical and cultural heritage,” Life Sci. J., vol. 11, p. 634, 2014.

- T. H. Tuan and S. Navrud, “Capturing the benefits of preserving cultural heritage,” J. Cult. Herit., vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 326–337, 2008.

- H. Radoine, “Environmental , and Economic Development : The Case of the Walled City of Fez,” Hum. Sustain. City Challenges Perspect. from Habitat Agenda, ed. Luigi Fusco Girard, p. Pp.458-476, 2003.

- Torre, “Assessing the values of cultural heritage. Assessing values in conservation planning: Methodological issues and choices. Los Angeles:,” Getty Conserv. Institute., 2002.

- D. C. S. Dr. B. Shankar, “Creating Awareness for Heritage Conservation in the City of Mysore: Issues and Policies,” Ijmer, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 698–703, 2013.

- C. F. Chen and S. Z. Chiou-Wei, “Tourism expansion, tourism uncertainty and economic growth: New evidence from Taiwan and Korea,” Tour. Manag., vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 812–818, 2009.

- I. Cortés-jiménez, “Which Type of Tourism Matters to the,” Int. J. Tour. Res., vol. 139, no. September 2001, pp. 127–139, 2008.

- T. Mihalič, “Environmental management of a tourist destination: A factor of tourism competitiveness,” Tour. Manag., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 65–78, 2000.

- C. Tweed and M. Sutherland, “Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development,” Landsc. Urban Plan., vol. 83, no. 1, pp. 62–69, 2007.

- A. P. Russo, “The ‘vicious circle’ of tourism development in heritage cities,” Ann. Tour. Res., vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 165–182, 2002.

- Herbert, “Heritage places, leisure and tourism,” Heritage, Tour. Soc., no. 1, p. 29201, 1995.

- Khirfan, World heritage, urban design and tourism: Three cities in the Middle East. 2014.

- T. Silberberg, “Cultural tourism and business opportunities for museums and heritage sites,” Tour. Manag., vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 361–365, 1995.

- Timothy, Cultural heritage and tourism. 2011.

- I. Rizzo and D. Throsby, “Chapter 28 Cultural Heritage: Economic Analysis and Public Policy,” Handb. Econ. Art Cult., vol. 1, no. 06, pp. 983–1016, 2006

- A. L. and Rinaldo Brau and F. Pigliaru, “How Fast are the Tourism Countries Growing? The cross-country evidence,” FEEM, 2003

- Goodenough, “Multiculturalism as the Normal Human Experience,” Appl. Anthropol. Am., pp. 89–96, 1987

- N. L. Tagemouati, “Patrimaine, tourisme et emploi. Cas du sud du Maroc,” 1999.

- IRCICA, “The First International Seminar on Traditional Carpets and Kilims in the Muslim World: Past, Present, and Future Prospects for Developing This Heritage in the Context of Continuous Changes of the Market Design, Quality, and Applied Techniques,” 1999

- UNESCO. (2015). Cultural Heritage. https://www.onthegotours.com/Morocco/UNESCO-World-Heritage-Sites