The COVID-19 vaccine is being rolled out globally. High and ongoing public uptake of the vaccine relies on health and social care professionals having the knowledge and confidence to actively and effectively advocate it. An internationally relevant, interactive multimedia training resource called COVID-19 Vaccine Education (CoVE) was developed using ASPIRE methodology. This rigorous six-step process included: (1) establishing the aims, (2) storyboarding and co-design, (3) populating and producing, (4) implementation, (5) release, and (6) mixed-methods evaluation aligned with the New World Kirkpatrick Model. Two synchronous consultations with members of the target audience identified the support need and established the key aim (Step 1: 2 groups: n = 48). Asynchronous storyboarding was used to co-construct the content, ordering, presentation, and interactive elements (Step 2: n = 14). Iterative two-stage peer review was undertaken of content and technical presentation (Step 3: n = 23). The final resource was released in June 2021 (Step 4: >3653 views). Evaluation with health and social care professionals from 26 countries (survey, n = 162; qualitative interviews, n = 15) established that CoVE has high satisfaction, usability, and relevance to the target audience. Engagement with CoVE increased participants’ knowledge and confidence relating to vaccine promotion and facilitated vaccine-promoting behaviours and vaccine uptake. The CoVE digital training package is open access and provides a valuable mechanism for supporting health and care professionals in promoting COVID-19 vaccination uptake.

- COVID-19

- vaccine

- healthcare

- social care

- digital

- health education

- health protection

1. Introduction

2. Current Research On Healthcare Curricula (CoVE)

| Level (1–4) † | Sub-Component | Measure a | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Reaction |

Reach | Channel for receipt of the resource a | |

| Through employer | 81 (50) | ||

| Through educational institution | 22 (13.6) | ||

| Via professional network | 35 (21.6) | ||

| Recommended by peer/colleague | 22 (13.6) | ||

| Through digital catalogues | 3 (1.8) | ||

| Other route (e.g., family, manager) | 9 (5.6) | ||

| User a | |||

| Health or care professional | 116 | ||

| University or college students | (71.6) | ||

| Tutor/teacher/lecturer | 22 (13.6) | ||

| General public | 16 (9.9) | ||

| Other (e.g., public health specialist/ | 8 (4.9) | ||

| researcher, professional network manager) | 20 (12.3) | ||

| “in Indonesia particularly, we are struggling for vaccination today.by providing this educational package it helps health care professional to explain clearly for the patients the technical point.of vaccinations that it will make and convince people to get vaccinated.” (109) |

|||

| Use | Easy to use | 160 (98.8) | |

| Helpful or very helpful rating | 162 (99.4) | ||

| Problems with use (% yes) | |||

| No problems | 152 (93.8) | ||

| Technical issues | 7 (4.3) | ||

| Level of difficulty | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Language difficulty | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Contextual or cultural differences | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Other issues (e.g., personal device | 3 (1.9) | ||

| issue, lack of time to complete) | |||

| “easy to follow and informative and it wasn’t too long but I felt it covered everything that needed to be covered” (114) “we have a lot of staff who English is not their first language and I felt it was understandable and easy” (105) “a variety of ways of accessing the information” (S) |

|||

| Satisfaction | Good or excellent rating | 161 (99.9) | |

| Would recommend to others | 160 (98.8) | ||

| “I would say this is, I think, is the material that I was looking for. I am really impressed with this” (106) “this is very beneficial for us, our welfare. Removing the rumours about. the COVID-19” (110) “brief and to the point, but extensive extra resources giving further detail if you want it” (S) |

|||

| Engagement | View towards interactive elements: “very interactive and engaging—information buttons to explain all the terms, text boxes to expand, images, videos, narration and additional reading. I revisit it and find more information each time” (S) “the graphics of it, the way it was quite interactive, you can click on different things. you don’t have to sit and read. You could just listen to it and that was really good” (113) |

||

| Relevance | Relevance to self or others: “I think this one is really timely because the level of vaccine hesitancy among nurses in the Philippines is a bit high as well” (106) “the patient experiences. I feel these are the stories that will help others understand the need more” (S) “I know a lot of my colleagues, it’s information they don’t have access to” (102) “I work in.the front line.COVID dilemmas happen every day. So, yes, I, I do believe that this information is pertinent” (112) “contain a very reliable information that we can share to the patient and convince them’ (109) |

||

| (2) Learning |

Knowledge | Pre-knowledge score ≥ 8/10 | 57 (35.2) |

| Post-knowledge score ≥ 8/10 | 138 (84.6) | ||

| Learned something new (% yes) | 139 (85.8) | ||

| “almost everything is new for me in this resource” (115) “I found the explanation of the clinical trials and the different phases quite useful ‘cause that wasn’t something I knew about and it’s where a lot information I’ve seen being spread through social media is about.” (102) “it gave me better insight into the actual client t hat I’m dealing with and all the emotions” (111) |

|||

| Skill | Feeling equipped with useful knowledge: “now.I’m armed with new information and how to explain it to them [patients]” (106) “the learning is really related to how to present the facts.really hones in on how to communicate that knowledge I think” (114) “It would help me facilitate a conversation about COVID to people” (112) |

||

| Attitude | Views towards COVID-19 vaccine: “after assessing the resource it makes me more confident about the vaccines” (109) “I can imagine if somebody was very anxious, and quite sceptical. I think this this will be very good for them” (113) “It will erase their individual beliefs about the negative things about or information about COVID-19 vaccine” (107) “it strengthened my belief now that now we have to tell people the correct information” (106) “I wouldn’t say it changed my views ‘cause I was always very positive about the vaccination…but it has cemented t hem.” (105) “I manage a care company with 108 staff, 13 of those are currently refusing the vaccination. I wish to support them to gain further correct knowledge to hopefully dispel any fears and take up the vaccine” (S) |

||

| Confidence | Pre-confidence score ≥ 8/10 | 72 (44.5) | |

| Post-confidence score ≥ 8/10 | 130 (80.2) | ||

| “now that I have this resource behind me. It [gives me] more credibility. It’s not just my opinion now” (105) “There are lot of rumours regarding the negative reaction of vaccine in my society, but by using this resource I can better explain the effectiveness of vaccine with opponents and encourage them to get vaccine.” “gave me more confidence. it was very transferable knowledge” (112) “in terms of talking to a stranger about vaccines and, you know, how they work, I’m more confident now” (101) |

|||

| Commitment | Estimated future use and resource sharing: “I’m going to promote this material because this is relevant. There’s no such materials, I would say at the moment in the Philippines.” (106) “we’ve got some healthcare staff that are resistant.because of the propaganda.I would be quite happy to use this resource in a discussion forum with a group of staff. To enable us to have those difficult conversations really” (105) “I definitely share the package to my students.” (110) “support workers.or students. I could use that knowledge to help and support them for s ure” (103) |

||

| (3) Transfer/ Behaviour |

Behaviour changes |

User application of knowledge and reported behavioural changes: “I have already applied it. I applied it on my family because I am encouraging my parents to get vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine. they are afraid to get vaccinated.” (109) “I have shared this resource to all my family members, society and colleagues. I have planned to conduct awareness session at District level.” (115) “I have applied this at my workplace and shared link. among my colleagues and representatives of NGOs [non-profit organisations]. They all given me a good response.” (115) |

|

| Required drivers |

Target audiences and mechanisms for dissemination “Maybe in the pharmacy, actually like community pharmacists when patients come in to get the medicine” (113) “I think nurses are a good place to start because they can, they can pass the knowledge onto others. Students are a good one I think because obviously they’re going into all these different places and meeting all these different people” (101) “looking at more of the health care assistants… I think I’ve found that they’re the ones who are more likely to have their own misunderstandings, which makes it harder for them to give suitable information to patients” (102) “State Governments may adopt this for sharing through Health Departments” (115) “In our place, there a lot of rural area where they don’t have much, uh, like cell phones or technology. So probably we, we can have like giving them a hard copy about this” (107) “We talked at the vaccination centre about how it might be useful for everybody to do and be part of the training process. I’ve shared it on WhatsApp and quite a few people have done it already. I also shared it in my trust with our new vaccination lead” (114) |

||

| (4) Results/ Impact |

Leading indicators |

Changes in user confidence or communication; Resulting patient, client or general public actions; Additional perceived benefits or applications: “I am about to receive a vaccine this weekend” (S) “Being able to answer the questions about how they got a vaccine available so quickly, which is the one I seem to be faced with a lot. [I am] having these conversations with the public” (102) “I’ve shared the knowledge presented in the package to my colleague and now as well as my family.they become more confidenced that this is one of our way to protect our family and our self” (109) “I have applied this knowledge and I am shocked that I have convinced each of them to take vaccine and answers their queries better and changed their view and mind about the negativity of vaccine. It is wonderful experience and I have observed that if one’s can explain better, he definitely will get the goals”. (115) |

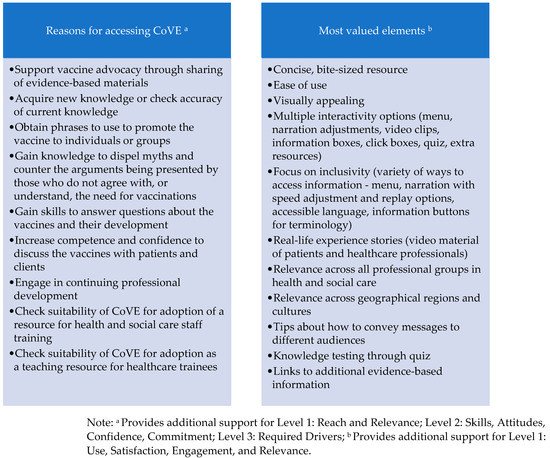

2.1. Level 1 (Reaction: Reach, Use, Satisfaction, Engagement, Relevance)

2.2. Level 2 (Learning: Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, Confidence, Commitment)

2.3. Level 3 (Transfer/Behaviour and Required Drivers)

2.4. Level 4 (Impact)

3. Conclusions

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Uttarilli, A.; Amalakanti, S.; Kommoju, P.R.; Sharma, S.; Goyal, P.; Manjunath, G.K.; Upadhayay, V.; Tandon, R.; Prasad, K.S.; Dakal, T.C.; et al. Super-rapid race for saving lives by developing COVID-19 vaccines. Integr. Bioinform. 2021, 18, 27–43.

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160.

- Robinson, E.; Jones, A.; Lesser, I.; Daly, M. International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2024–2034.

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines 2020, 9, 16.

- Mahase, E. COVID-19: UK has highest vaccine confidence and Japan and South Korea the lowest, survey finds. BMJ 2021, 373, n1439.

- World Health Organization. Behavioural Considerations for Acceptance and Uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines: WHO Technical Advisory Group on Behavioural Insights and Sciences for Health; Meeting Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1320080/retrieve (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Dubé, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J.A. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773.

- Eniola, K.; Sykes, J. Four Reasons for COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Health Care Workers, and Ways to Counter Them. Online. 2021. Available online: https://www.aafp.org/journals/fpm/blogs/inpractice/entry/countering_vaccine_hesitancy.html (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Eid, H.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Al-Haidar, A.; Taim, D.; Yaseen, A.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 42.

- Paris, C.; Bénézit, F.; Geslin, M.; Polard, E.; Baldeyrou, M.; Turmel, V.; Tadié, E.; Garlantezec, R.; Tattevin, P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Infect. Dis. Nowf. 2021, 51, 484–487.

- Kwok, K.; Li, K.K.; Wei, W.I.; Tang, A.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Lee, S.S. Influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: A survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 114, 103854.

- Wang, K.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Ho, K.F.; Cheung, A.W.L.; Chan, E.Y.Y.; Yeoh, E.K.; Wong, S.Y.S. Intention of nurses to accept coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination and change of intention to accept seasonal influenza vaccination during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7049–7056.

- Gadoth, A.; Halbrook, M.; Martin-Blais, R.; Gray, A.; Tobin, N.H.; Ferbas, K.G.; Aldrovandi, D.M.; Rimoin, A.W. Assessment of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers in Los Angeles. medRxiv 2020.

- Aurilio, M.T.; Mennini, F.S.; Gazzillo, S.; Massini, L.; Bolcato, M.; Feola, A.; Ferrari, C.; Coppeta, L. Intention to Be Vaccinated for COVID-19 among Italian Nurses during the Pandemic. Vaccines 2021, 9, 500.

- Fares, S.; Elmnyer, M.M.; Mohamed, S.S.; Elsayed, R. COVID-19 Vaccination Perception and Attitude among Healthcare Workers in Egypt. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 21501327211013303.

- Bauernfeind, S.; Hitzenbichler, F.; Huppertz, G.; Zeman, F.; Koller, M.; Schmidt, B.; Plentz, A.; Bauswein, M.; Mohr, A.; Salzberger, B. Brief report: Attitudes towards Covid-19 vaccination among hospital employees in a tertiary care university hospital in Germany in December 2020. Infection 2021, 49, 1307–1311.

- Martin, C.A.; Marshall, C.; Patel, P.; Goss, C.; Jenkins, D.R.; Ellwood, C.; Barton, L.; Price, A.; Brunskill, N.J.; Khunti, K.; et al. Association of demographic and occupational factors with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine uptake in a multi-ethnic UK healthcare workforce: A rapid real-world analysis. medRxiv 2021.

- Royal Society for Public Health. New Poll Finds BAME Groups Less Likely to Want COVID Vaccine. 2020. Available online: https://www.rsph.org.uk/about-us/news/new-poll-finds-bame-groups-less-likely-to-want-covid-vaccine.html (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Elhadi, M.; Alsoufi, A.; Alhadi, A.; Hmeida, A.; Alshareea, E.; Dokali, M.; Abodabos, S.; Alsadiq, O.; Abdelkabir, M.; Ashini, A.; et al. Knowledge, attitude, and acceptance of healthcare workers and the public regarding the COVID-19 vaccine: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–21.

- Paterson, P.; Meurice, F.; Stanberry, L.R.; Glismann, S.; Rosenthal, S.L.; Larson, H.J. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine 2016, 34, 6700–6706.

- Kreps, S.; Prasad, S.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hswen, Y.; Garibaldi, B.T.; Zhang, B.; Kriner, D.L. Factors Associated With US Adults’ Likelihood of Accepting COVID-19 Vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2025594.

- Collange, F.; Zaytseva, A.; Pulcini, C.; Bocquier, A.; Verger, P. Unexplained variations in general practitioners’ perceptions and practices regarding vaccination in France. Eur. J. Pub. Health 2019, 29, 2–8.

- Karafillakis, E.; Dinca, I.; Apfel, F.; Cecconi, S.; Wűrz, A.; Takacs, J.; Suk, J.; Celentano, L.P.; Kramarz, P.; Larson, H.J. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in Europe: A qualitative study. Vaccine 2016, 34, 5013–5020.

- Karlsson, L.C.; Lewandowsky, S.; Antfolk, J.; Salo, P.; Lindfelt, M.; Oksanen, T.; Kivimäki, M.; Soveri, A. The association between vaccination confidence, vaccination behavior, and willingness to recommend vaccines among Finnish healthcare workers. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224330.

- Napolitano, F.; Navaro, M.; Vezzosi, L.; Santagati, G.; Angelillo, I.F. Primary care pediatricians’ attitudes and practice towards HPV vaccination: A nationwide survey in Italy. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194920.

- Bono, S.A.; Villela, E.F.M.; Siau, C.S.; Chen, W.S.; Pengpid, S.; Hasan, T.; Sessou, P.; Ditekemena, J.D.; Amodan, B.O.; Hosseinipour, M.C.; et al. Factors Affecting COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: An International Survey among Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 515.

- Unroe, K.T.; Evans, R.; Weaver, L.; Rusyniak, D.; Blackburn, J. Willingness of Long-Term Care Staff to Receive a COVID-19 Vaccine: A Single State Survey. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 593–599.

- Blake, H.; Gartshore, E. Workplace wellness using online learning tools in a healthcare setting. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 20, 70–75.

- Regmi, K.; Jones, L. A systematic review of the factors—Enablers and barriers—Affecting e-learning in health sciences education. BMC Med Educ. 2020, 20, 91.

- Blake, H. Computer-based learning objects in healthcare: The student experience. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2010, 7, 16.

- McCord, L.; McCord, W. Online learning: Getting comfortable in the cyber class. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2010, 5, 27–32.

- McVeigh, H. Factors influencing the utilisation of e-learning in post-registration nursing students. Nurs. Educ. Today 2009, 29, 91–99.

- Carroll, C.; Booth, A.; Papaioannou, D.; Sutton, A.; Wong, R. UK health-care professionals’ experience of on-line learning techniques: A systematic review of qualitative data. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2009, 29, 235–241.

- Windle, R.; Wharrad, H.; Coolin, K.; Taylor, M. Collaborate to create: Stakeholder participation in open content creation. In Association for Learning Technology Conference (ALT-C) Connect, Collaborate, Create; University of Warwick: Coventry, UK, 2016.

- Kirkpatrick, J.D.; Kirkpatrick, W.K. Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Training Evaluation; ATD Press: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2016.

- Kirkpatrick, D.L. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994.

- Windle, R.J.; McCormick, D.; Dandrea, J.; Wharrad, H. The characteristics of reusable learning objects that enhance learning: A case-study in health-science education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 42, 811–823.

- Leeder, D.; McClachlan, J.; Rodrigues, V.; Stephens, N.; Wharrad, H.J.; McElduff, P. UCeL: A virtual community of practice in health professional education. In Proceedings of the IADIS International, Lisbon, Portugal, 24–26 March 2004; pp. 386–393.

- Benyon, D.; Turner, P.; Turner, S. Designing Interactive Systems: People, Activities, Contexts, Technologies; Pearson Education: Edinburg, UK, 2005.

- Wharrad, H.; Windle, R.; Taylor, T. Designing Digital Education and Training for Health; Digital Innovations in Healthcare Education and Training, Konstantinidis, S.T., Bamidis, P.D., Zary, N., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2003.

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: A Brief Introduction. Available online: https://www.ewenger.com/theory/index.htm (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Taylor, M.; Henderson, J.; Windle, R.; Wharrad, H.; Coolin, K.; Riley, S. Collaboration in the Heart of the MOOC. In Association for Learning Technology Conference (ALT-C) Connect, Collaborate, Create; University of Warwick: Coventry, UK, 2016.

- Kurt, S. “Kirkpatrick Model: Four Levels of Learning Evaluation,” in Educational Technology. 2016. Available online: https://educationaltechnology.net/kirkpatrick-model-four-levels-learning-evaluation/ (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Gov.UK. Ethnicity Facts and Figures. Available online: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Gov.UK. NHS Workforce. Available online: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/workforce-and-business/workforce-diversity/nhs-workforce/latest (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- United States Census Bureau. Population Estimates. 2019. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Sex, Race, and Ethnic Diversity of U.S, Health Occupations (2011–2015). Rockville, Maryland, 2017. Available online: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/data-research/diversity-us-health-occupations.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Wharrad, H.J.; Morales, R.; Windle, R.; Bradley, C. A toolkit for a multilayered, cross-institutional evaluation strategy. In World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE): Chesapeake, WV, USA, 2008; pp. 4921–4925.

- Boniol, M.; McIsaac, M.; Xu, L.; Wuliji, T.; Diallo, K.; Campbell, J. Gender Equity in the Health Workforce: Analysis of 104 Countries. Health Workforce Working Paper 1. 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311314/WHO-HIS-HWF-Gender-WP1-2019.1-eng.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117.

- Evans, C. Development and Evaluation of ‘Reusable Learning Objects’ (RLOs) to Enhance the Learning Experience of International Healthcare Students. Available online: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/resources/nottingham_evans_connections_final_report.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Ferguson, M.; Maidment, D.; Henshaw, H.; Gomez, R. Knowledge Is Power: Improving Outcomes for Patients, Partners, and Professionals in the Digital Age. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups. 2019. Available online: https://www.c2hearonline.com/docs/Ferguson_etal_ASHA_SIG_7_2019.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Lymn, J.S.; Bath-Hextall, F.; Wharrad, H.J. Pharmacology education for nurse prescribing students—A lesson in reusable learning objects. BMC Nurs. 2008, 7, 2.

- Williams, J.; O’Connor, M.; Windle, R.; Wharrad, H.J. Using reusable learning objects (rlos) in injection skills teaching: Evaluations from multiple user types. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 1275–1282.

- Statista. Rate of COVID-19 Vaccine Doses Administered Worldwide as of October 1, by Country or Territory. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1194939/rate-covid-vaccination-by-county-worldwide/ (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Clark, R.C.; Mayer, R.E.E. Learning and the Science of Instruction; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003.

- Mayer, R.E. The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005.

- Laurillard, D. Rethinking University Teaching: A Framework for the Effective Use of Educational Technology, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002.

- Sabry, K.; Baldwin, L. Web-based learning interaction and learning styles. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2003, 34, 443–454.

- Local Government Association (LGA). Applying Behavioural Insights to Improve COVID Vaccination Uptake: A Guide for Councils. 22 April 2021. Available online: https://www.local.gov.uk/publications/applying-behavioural-insights-improve-covid-vaccination-uptake-guide-councils (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Smith, L.E.; Amlôt, R.; Weinman, J.; Yiend, J.; Rubin, G.J. A systematic review of factors affecting vaccine uptake in young children. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6059–6069.

- Bode, L.; Vraga, E.K. See something, say something: Correction of global health misinformation on social media. Health Commun. 2018, 33, 1131–1140.

- Our World in Data. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations: Share of People Vaccinated against COVID-19. 11 October 2021. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Khubchandani, J.; Sharma, S.; Price, J.H.; Wiblishauser, M.J.; Sharma, M.; Webb, F.J. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: A Rapid National Assessment. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 270–277.

- Wong, L.P.; Alias, H.; Danaee, M.; Ahmed, J.; Lachyan, A.; Cai, C.Z.; Lin, Y.; Hu, Z.; Tan, S.Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine characteristics influencing vaccination acceptance: A global survey of 17 countries. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 122.

- Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus Vaccine Hesitancy Falling across the Regions and Countries of Great Britain. 9 August 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/articles/coronavirusvaccinehesitancyfallingacrosstheregionsandcountriesofgreatbritain/2021-08-09 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Dubé, E.; Gagnon, D.; Nickels, E.; Jeram, S.; Schuster, M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy—Country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6649–6654.

- de Figueiredo, A.; Simas, C.; Karafillakis, E.; Paterson, P.; Larson, H.J. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: A large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet 2020, 396, 898–908.

- Solís Arce, J.S.; Warren, S.S.; Meriggi, N.F.; Scacco, A.; McMurry, N.; Voors, M.; Syunyaev, G.; Malik, A.A.; Aboutajdine, S.; Adeojo, O.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1385–1394.

- DeRoo, S.S.; Pudalov, N.J.; Fu, L.Y. Planning for a COVID-19 Vaccination Program. JAMA 2020, 323, 2458–2459.

- Kerr, J.R.; Schneider, C.R.; Recchia, G.; Dryhurst, S.; Sahlin, U.; Dufouil, C.; Arwidson, P.; Freeman, A.L.J.; van der Linden, S. Correlates of intended COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across time and countries: Results from a series of cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open 2021, 8, 8.

- Kempe, A.; O’Leary, S.T.; Kennedy, A.; Crane, L.A.; Allison, M.A.; Beaty, B.L.; Hurley, L.P.; Brtnikova, M.; Jimenez-Zambrano, A.; Stokley, S. Physician response to parental requests to spread out the recommended vaccine schedule. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 666–677.

- Walker, R.; Bennett, C.; Kumar, A.; Adamski, M.; Blumfield, M.; Mazza, D.; Truby, H. Evaluating Online Continuing Professional Development Regarding Weight Management for Pregnancy Using the New World Kirkpatrick Model. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2019, 39, 210–217.

- Moreau, K.A.; Eady, K.; Sikora, L.; Horsley, T. Digital storytelling in health professions education: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 208.

- Zielińska-Tomczak, L.; Przymuszała, P.; Tomczak, S.; Krzyśko-Pieczka, I.; Marciniak, R.; Cerbin-Koczorowska, M. How Do Dieticians on Instagram Teach? The Potential of the Kirkpatrick Model in the Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Nutritional Education in Social Media. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2005.

- Brown, R.C.; Straub, J.; Bohnacker, I.; Plener, P.L. Increasing Knowledge, Skills, and Confidence Concerning Students’ Suicidality Through a Gatekeeper Workshop for School Staff. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1233.

- Mutebi, N. COVID-19 vaccine coverage and targeted interventions to improve vaccination uptake: Rapid response. UK Parliament, Published Friday. 2 July 2021. Available online: https://post.parliament.uk/covid-19-vaccine-coverage-and-targeted-interventions-to-improve-vaccination-uptake/ (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Blake, H.; Bermingham, F.; Johnson, G.; Tabner, A. Mitigating the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers: A Digital Learning Package. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2997.