In Italy, drug expenditure governance is achieved by setting caps based on the percentage increase in hospital spending compared to the previous year. This method is ineffective in identifying issues and opportunities as it does not consider an analysis of the number of treated cases and per capita consumption in local and regional settings. The IRCCS (Scientific hospitalization and treatment institute) Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori” in Meldola, has developed and adopted an effective management model designed to oversee pharmaceutical expenditure, guarantee prescription appropriateness and quality of care to patients. The budget setting follows a structured process which evaluates determining factors of the expenditure such as expected patients calculated according to the epidemiology and to national and regional indications of appropriateness, mean cost per patient calculated on the average period of demonstrated efficacy of the drug and use of drugs with the best cost-effectiveness ratio. Strict monitoring and integrated purchasing processes allow for immediate corrective actions on expenditures, as well as a continuous dialogue with the region in order to guarantee consistent funding of IRST activities.

1. Introduction

Recently, attention in pharmaceutical governance has focused on hospital channel expenses (c.d. direct purchases, i.e., drugs purchased by the health facilities of the NHS (National Health Sistem), including class-based drugs in direct distribution and on behalf of, considered as distribution, directly to patients for use at home). This type of expense has grown more than the gross cost for class A drugs (drugs paid for and distributed by the National Health System, not for hospital use only) distributed directly to patients by hospital pharmacies or through territorial pharmacies (direct purchasing), more than a quarter of which are oncology drugs (26% in 2019).

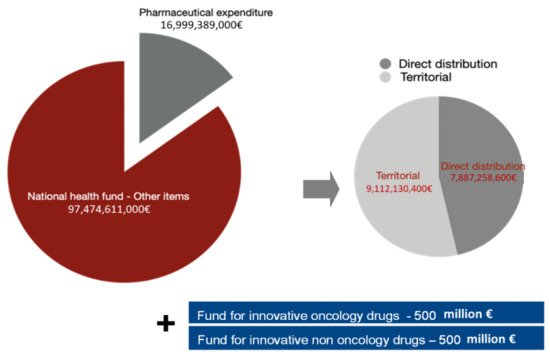

Pharmaceutical expenditure represents a significant part of the resources that the Italian government annually spends on healthcare (EUR 23.5 billion in 2019 approximately 21.4% of FSN, National Healthcare Fund

[1]).

In Italy, according to the logic of a silo budget, the national cap for pharmaceutical expenditure is defined as a percentage of total funding for health expenses (National healthcare fund—FSN), supported by a rigid monitoring mechanism to ensure compliance and contain overspending

[2]. These are mostly represented by paybacks, supported by more sophisticated mechanisms such as MEAs (Managed Entry Agreements) with much lower impact.

The total percentage of pharmaceutical expenditure on the national health fund remained at 14.85%, but the territorial cap was reduced to 7.96%. Fluctuations in hospital expenditure for drug purchase impact more than territorial variations, confirming the need for more stringent governance and monitoring

[3].

Two additional Funds were also established in 2017, each with a maximum expenditure of EUR 500 million dedicated, respectively, to innovative oncological and non-oncological drugs

[4][5] (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Composition of pharmaceutical expenditure and national health fund (NHF).

New rules and regulations concerning the switching to biological drugs with their biosimilars and the purchase of biological drugs with expired patents were also established

[6]. The above-mentioned tools generated a silo approach.

Pharmaceutical expenditure for direct purchases has grown constantly beyond the established cap, despite the tools implemented at a national level, maintaining the already present state of fundamental structural under-financing. The monitoring report by the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) for January–December 2019 showed an over-expenditure of 6.89% above the target, which translated into a deviation, in absolute terms, of approximately 2.6 billion euro, equal to 9.02% on the NHF

[1]. In 2018, the same monitoring report by AIFA showed an overall overrun of €2.2 billion with a total impact on the NHF of 8.85%

[7]. This overshoot was evident, although in different proportions, in all Italian regions. The innovative oncological drugs fund, established in 2017, was initially underused (402 million euro in 2017), but in 2018 recorded a strong increase due to the overall under-financing of hospital pharmaceutical expenditure (over 600 million euro in 2018) and the continuous increase in expenditure for cancer drugs in the EU

[8].

This Italia system to contain healthcare and pharmaceutical spending generates a silo model, that is, a model managed through expenditure caps that are not communicating with each other. One of the major limitations of this system is that it does not allow those who administer the health facilities to merge any residual funds into the other items. The IRST of Meldola created a budgeting model presented in the article, and that represents one of the many ways of dealing with a silo system and respecting national sales cap and obligations.

2. Current Insights

In Europe, several countries have adopted a drug budgeting silo technique

[9]. In France, Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, even though national healthcare systems handle drug expenditure in different ways, at least once a clear case of “silo budgeting” has been applied and a national-level drug budget has been defined as a target. Only the United Kingdom, thereafter, abolished national drug-spending targets in favor of an integrated budget with local allocations for spending. Yet, in defining local budgets, each country adopts different systems. Spain and Italy mandated budgetary control to the regions maintaining national targets. In France

[10], at the national level, budgets are set by the parliament based on GDP (Gross Domestic Product) growth, public sector deficits, and other macro criteria. The German government

[11] established a national drug budget and allocated it among its 23 regions; each region has its own separate drug budget and a surplus in one region cannot be used to compensate for a deficit in another. A large variety of mechanisms were proposed for monitoring “over prescription” (i.e., regional drug budgets, drug budgets per physicians, copayment), but after initially positive results, the process was found to be ineffective.

The new funds for innovative oncological drugs in the Italian national and regional health system use innovation with reduced time, improve patient access and allow better planning capacity than methods based on historical expenditure; all positive and ameliorative aspects. This process allows homogeneity in the use of innovative drugs among different territories.

On the other hand, drug expenditure for oncological drugs, based on the two available funds on a national and regional level, have the following limits:

-

Establishment of expenditure caps without considering the number of patients and patient case-mix which encourages potential inappropriate behavior by providers who exceed maximum expenditure during the year;

-

Management by non-communicating “silos” (fund for direct purchases, territorial pharmaceutical fund, funds for oncological and non-oncological innovation, etc.) that does not consider compensation between funds.

The innovative and positive aspects may prevail over the potential drawbacks if two conditions are met:

-

Programming is as well calibrated as possible (based on concurrent epidemiological data, needs and appropriateness);

-

A certain degree of flexibility is allowed during the year according to unforeseen events, such as different patient flows between the various providers, new clinical evidence, new therapies available.

If these conditions can be satisfied, the programming tools applied to the funds for innovative drugs should be extended to all high-cost oncological drug spending, which requires refined, evolved and complex governance tools. The generally accepted budget assessment based on historical spending should be replaced by a method that allows production factors analysis governed by consumption evaluations and expenditure weights per capita weighted expenditure, commonly used for territorial pharmaceutical spending.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, the correct management of health expenses in the last years has become key in all European countries; defining value-based healthcare models to correctly allocate economic resources means taking care of patients more appropriately and with the latest available technology.

In the complex setting of oncological drug management, in which limited and insufficient public resources are available, the use of digitalized, multi-factorial analysis and decision-making alternatives may aid in sustainable management.

In order to do that, it is necessary to use sophisticated tools (computerized tools) that allow a detailed, periodic, and timely monitoring of a complex system of a defined set of measures and indicators of needs, appropriateness, and expenditure, in line with healthcare services demand. The IRST of Meldola, organized in a matrix based on pathology groups (GdPs), has developed over the years advanced tools for the analysis of needs, consumption, and expenditure of oncological drugs, specific for each disease, with a budgeting model focused on its determinants (appropriate and inappropriate) rather than on expenditure and measured with a set of indicators set based on the objectives of each UO (Operating Units). Thanks to this model, IRST has made the most out of the management innovations described above also in the dialogue with the regional authorities, promoting their implementation. A significant evolution in the governance of oncological pharmaceutical expenditure has great potential to succeed.

These tools will ensure universal and timely access to therapeutic innovation in the field of oncology.

The model of IRST represents a way to allocate economic resources in taking care of patients, quality of care and support hospital structures in considering and including in decisions (economical and healthcare related) all information derived from institutional and clinical sources and represents an answer to the need of respect in national and regulatory directives in terms of health expenditure but also a way to address decisions in a value-based way through an accurate needs and scenario analysis. The proposed model attempts to provide a contribution for the governance of oncology drugs according to the described environment.