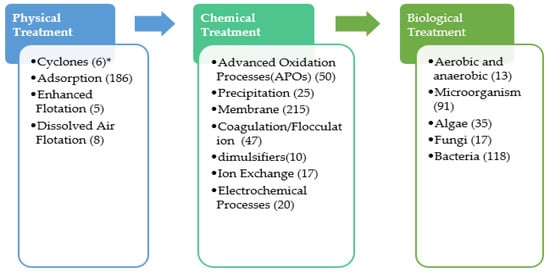

Produced water (PW) is the most significant waste stream generated in the oil and gas industries. The generated PW has the potential to be a useful water source rather than waste. While a variety of technologies can be used for the treatment of PW for reuse, biological-based technologies are an effective and sustainable remediation method. Specifically, microalgae, which are a cost-effective and sustainable process that use nutrients to eliminate organic pollutants from PW during the bioremediation process. In these treatment processes, microalgae grow in PW free of charge, eliminate pollutants, and generate clean water that can be recycled and reused. This helps to reduce CO2 levels in the atmosphere while simultaneously producing biofuels, other useful chemicals, and added-value products.

- produced water

- oil and gas production

- BTEX removal

- biological treatment

- microalgae

1. Introduction

32. Produced Water

3.1. Produced Water Generation

2.1. Produced Water Generation

| 0.009–23 | ||

| [ | ||

| 6 | ||

| ] | ||

| [ | ||

| 26 | ||

| ] | ||

| [ | ||

| 28 | ||

| ] | ||

| Potassium ion ( | ||

| K+) | 24–4300 | |

| pH | 4.3–10 | [4] |

| Strontium ion (Sr+) | 0–6250 | |

| Total organic acids |

| Parameter | Raw Produced Water | Filtered Water |

|---|---|---|

| Total organic carbon (mg/L) | 389.1 | 317 |

| Total nitrogen (mg/L) | 35.77 | 27.6 |

| Total phosphorus (μg/L) | 277.78 | 180 |

| Benzene (mg/L) | 21 | 16.1 |

| Toluene (mg/L) | 3.8 | 3.21 |

| Ethylbenzene (mg/L) | 1.22 | 1.05 |

| Xylene (mg/L) | 3.43 | 3.11 |

3.2. Characteristics of Produced Water

2.2. Characteristics of Produced Water

Produced water characteristics vary between regions and a specific study for each area should be conducted to investigate the effects of PW discharge on the environment [8,18][8][17]. Further, PW contains a complex composition of physical and chemical properties, dependent on the geological formation, geographic field [5], extraction method, and the type of extracted hydrocarbon [6]. Rahman et al. [1] detail a list of PW parameters and their typical range. It was observed that the toxicity of the PW generated from gas wells is 10 times greater than the toxicity produced from oil wells [5]. Given that, special treatment should be taken for PW from oil wells. The composition of PW from oil fields is summarized in Table 32. The primary constitutes found in PW are total dissolved solids (TDS), salts, benzene (B), toluene (T), ethylbenzene (E), and xylenes (X) (denoted as BTEX), polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), oil and grease (O&G). The BTEX are volatile organic compounds that naturally occur in oil and gas wells, including gasoline and natural gas. The BTEX compounds also freely escape into the atmosphere during PW treatment [31][25]. Additionally, traces of natural organic and inorganic compounds, phenol, organic acids, and chemical additives added during the drilling process can be found in PW and contribute to its total toxicity [5].| Chemical oxygen demand (COD) | 1220–2600 | [4][6][8][26][27] |

| Sodium ions (Na+) | 0–150,000 | |

| Total suspended solids (TSS) | 1.2–1000 | [4][6][8][19][26][27] |

| Calcium ion (Ca2+) | 0–74,000 | |

| Total polar compounds | 9.7–600 | [6][8][28] |

| Boron (B) | 5–95 | |

| Total dissolved solids (TDS) | 100–400,000 | [8][28] |

| Chlorine (Cl−) | 0–270,000 | |

| BTEX; benzene (B), toluene (T), ethylbenzene (E), and xylenes (X) | 0.73–24.1 | [4][26] |

| Magnesium (Mg2+) | 8–6000 | |

| Total organic compound (TOC) | 0–1500 | [4][6][19][26][27] |

| Iron(II) (Fe2+) | 0.1–1100 | |

| Total oil and grease | 2–565 | [28] |

| Barium ion (Ba2+) | 0–850 | |

| Phenol | 0.001–10,000 | [4] |

| Aluminium (Al3+) | 310–340 | |

| Lithium (Li+) | 3–40 | [4][26] |

| Lead (Pb) | 0.008–0.08 | |

| Bicarbonate (HCO−3) | 0–15,000 | [8] |

| Arsenic (As) | 0.002–11 | |

| Sulfate (SO2−4) | 0–15,000 | [4][6][8] |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.004–175 | |

| Titanium (Ti) | 0.01–0.7 | [4][6] |

| Composition | Concentration Range (mg/L) | References |

|---|

| Microalgae Species | Type of Nutrients | Removal Efficiency% | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical oxygen demand (COD) | 1220–2600 | [4,6,8,32,33] | |

| Sodium ions (Na+ |

| Composition | Concentration Range (mg/L) | References |

| Zinc (Zn) | ||

| 0.01–35 | ||

| Dunaliella salina | Nitrogen Phosphorus heavy metal: Ni Zn |

65% 40% 90% 80% |

[63] | [40] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nannochloropsis oculata | Ammonium and Nitrogen Organic carbon Iron |

~100% 40% >90% |

[64] | [41] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Parachlorella kessleri | Benzene and Xylenes Toluene Ethylbenzene |

40% 63% 30% |

[65] | [42] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chlorella vulgaris | ( | C.v | ) | Neochloris oleoabundans | ( | N.o | ) | COD by ( | C.v | ) by ( | N.o | ) Ammonia by | C.v. | and | N.o | Phosphorus by | C.v. | and | N.o | 51%, 55% and 80% 63%, 47% and 72% (70–84%) (>84%), (>22%) and (<15%) |

[66] | [43] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Chromium Nickel |

11.24% 33.89% |

[67] | [44] | ||||||||||||||||||

| ) | 0–150,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Total suspended solids (TSS) | 1.2–1000 | [4,6,8,20,32,33] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Calcium ion (Ca2+ |

| ) | 0–74,000 | |

| Total polar compounds | 9.7–600 | [6,8,34] |

| Boron (B) | 5–95 | |

| Total dissolved solids (TDS) | 100–400,000 | [8,34] |

| Chlorine ( |

| Cultivation System | Algae Species | Cultivation Condition | Type of Waste | Biomass Productivity g/(L.d). | Organic Removal | Biofuel Type | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cl | |||||||

| − | |||||||

| ) | |||||||

| Closed system (PBRs) | Scenedesmus acutus (UTEX B72) | Agriculture-grade urea, triple super phosphate (TSP), pot ash and Sprint 330 (iron chelate) | Flue gas | 0.15 | Sulfur, NOx | [68] | [45] | |

| Closed system 4-L cylindrical photobioreactor (PBR) | ||||||||

| 0–270,000 | ||||||||

| BTEX; benzene (B), toluene (T), ethylbenzene (E), and xylenes (X) | 0.73–24.1 | [4,32] | ||||||

| Magnesium (Mg2+) |

| 8–6000 | ||

| Total organic compound (TOC) | 0–1500 | [4,6,20,32,33] |

| Iron(II) (Fe2+ |

| ) | 0.1–1100 | |

| Total oil and grease | 2–565 | [34] |

| Barium ion (Ba2+) |

| 0–850 | ||

| Phenol | 0.009–23 | [6,32,34] |

| Potassium ion (K+ |

| ) | 24–4300 | |

| pH | 4.3–10 | [4] |

| Strontium ion (Sr+ |

| Mixed culture of | ||||||||||||

| Chlorella vulgaris | ||||||||||||

| , | Scenedesmus Obliquus, Botryococcus braunii | , | Botryococcus sudeticus | , and | Afrocarpus falcatus | pH = 7, Temp = 25 °C. | 0.15 | 21, 60, and 47% for protein, carbohydrate and DOC, respectively | [69] | [46] | ||

| 500 mL glass flasks | Dunaliella tertiolecta | pH—8.1, Temp = 24 °C, f/2 medium | Real PW | 0.0172 @ salinity 30 gTDS/L to 0.0098 @ 201 gTDS/L | Biodiesel | [61] | [47] | |||||

| 500 mL glass flasks | Cyanobacterium aponinum, Parachlorella kessleri | pH—8.1, Temp = 24 °C, f/2 medium | Real PW | 0.113 * | Biodiesel | [70] | [48] | |||||

| Synechococcus | sp., | Cyanobacterium aponinum and Phormidium | sp. | pH = (6–9), | BG-11 medium | NA | Biodiesel | [71] | [49] | |||

| Chlorella | sp. and | Scenedesmus | sp. | pH = 7.1 | 0.115 * | Chlorella | sp.: remove 92% of the TN and 73% of the TOC | [72] | [50] | |||

| Dunaliella salina | Salinity 52.7–63.3 g/L NaCl | Real produced water | NA | Aluminum, barium, copper, magnesium, manganese, nickel, and strontium | Biodiesel | [59] | [51] | |||||

| Horizontal laminar air flow chamber | Chlorella pyrenoidosa | T = 121 °C | Fogg’s Medium, slant culture | NA | Biofuel and bioplastic | [67] | [44] | |||||

| ) | 0–6250 | |||||||||||

| Total organic acids | 0.001–10,000 | [4] | ||||||||||

| Aluminium (Al3+ |

| ) | 310–340 |

| Lithium (Li+ |

| ) | 3–40 | [4,32] |

| Lead (Pb) | 0.008–0.08 | |

| Bicarbonate (HCO−3 |

| ) | 0–15,000 | [8] |

| Arsenic (As) | 0.002–11 | |

| Sulfate (SO2−4 |

| ) | 0–15,000 | [4,6,8] |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.004–175 | |

| Titanium (Ti) | 0.01–0.7 | [4,6] |

| Zinc (Zn) | 0.01–35 |

3. Algae-Based Biological Processes

Microalgae are an encouraging technology for the treatment of WW [47,48,49,50,51,52][29][30][31][32][33][34]. For example, microalgae can uptake different constituents from PW and use them as a growth medium. Given that, algal cultures can solve both economic and environmental concerns and simultaneously produce biomass and other useful chemicals [53,54][35][36]. Establishing a sustainable green technology such as algae for PW treatment, recovery, and reuse contributes to the production of biomass, which can be converted into biofuel [48,54,55,56,57][30][36][37][38][39]. This conversion helps to eliminate and save natural gas. Moreover, naturally occurring microorganism seeds in PW can sequentially work with algae and increase the removal efficiency of organic matters and dissolved solids. In sequential processes, algae consume CO2 and produces O2, which are essential components for the survival of the microorganism. Table 53 presents the efficiencies of different microalgae strains and their ability to remove organic compounds and nutrients from wastewater. The removal efficiencies reached up to 50%, 65%, and ≥80% for nitrogen compounds, phosphorous, and heavy metals, respectively. Other constituent (i.e., COD and BETX) removals were related to the strain that was used. Algae-based wastewater treatment can also be performed in different systems as outlined in Table 64. Depending on the type of system used (i.e., open vs. closed), different removal efficiencies can be achieved.References

- Rahman, A.; Agrawal, S.; Nawaz, T.; Pan, S.; Selvaratnamm, T. A review of algae-based produced water treatment for biomass and biofuel production. Water 2020, 12, 2351.

- Lin, L.; Jiang, W.; Chen, L.; Xu, P.; Wang, H. Treatment of produced water with photocatalysis: Recent advances, affecting factors and future research prospects. Catalysts 2020, 10, 924.

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, H.; Pan, Z.; Dai, P.; Sun, G.; Yang, Q. A full-scale process for produced water treatment on offshore oilfield: Reduction of organic pollutants dominated by hydrocarbons. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126511.

- Fakhru’L-Razi, A.; Pendashteh, A.; Abdullah, L.C.; Biak, D.R.A.; Madaeni, S.S.; Abidin, Z.Z. Review of technologies for oil and gas produced water treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 170, 530–551.

- Duraisamy, R.T.; Beni, A.H.; Henni, A. State of the art treatment of produced water. In Water Treatement; InTech Open: London, UK, 2013; pp. 199–222.

- Jiménez, S.; Micó, M.M.; Arnaldos, M.; Medina, F.; Contreras, S. State of the art of produced water treatment. Chemosphere 2018, 192, 186–208.

- Zhang, Z.; Du, X.; Carlson, K.H.; Robbins, C.A.; Tong, T. Effective treatment of shale oil and gas produced water by membrane distillation coupled with precipitative softening and walnut shell filtration. Desalination 2019, 454, 82–90.

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Al-Kaabi, M.A.; Ashfaq, M.Y.; Da’na, D.A. Produced water characteristics, treatment and reuse: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 28, 222–239.

- Ali, A.; Quist-Jensen, C.A.; Drioli, E.; Macedonio, F. Evaluation of integrated microfiltration and membrane distillation/crystallization processes for produced water treatment. Desalination 2018, 434, 161–168.

- Riley, S.M.; Oliveira, J.; Regnery, J.; Cath, T.Y. Hybrid membrane bio-systems for sustainable treatment of oil and gas produced water and fracturing flowback water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 171, 297–311.

- Freedman, D.E.; Riley, S.M.; Jones, Z.L.; Rosenblum, J.S.; Sharp, J.O.; Spear, J.R.; Cath, T.Y. Biologically active filtration for fracturing flowback and produced water treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2017, 18, 29–40.

- Kiss, Z.L.; Kovacs, I.; Veréb, G.; Hodúr, C.; László, Z. Treatment of model oily produced water by combined pre-ozonation–microfiltration process. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 23225–23231.

- Lu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, W.; Zhu, W. Biological treatment of oilfield-produced water: A field pilot study. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2009, 63, 316–321.

- Camarillo, M.K. and Stringfellow, W.T. Biological treatment of oil and gas produced water: A review and meta-analysis. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2018, 20, 1127–1146.

- Caspeta, L.; Buijs, N.A.; Nielsen, J. The role of biofuels in the future energy supply. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1077–1082.

- De-Luca, R.; Bezzo, F.; Béchet, Q.; Bernard, O. Exploiting meteorological forecasts for the optimal operation of algal ponds. J. Process Control 2017, 55, 55–65.

- Graham, E.J.S.; Dean, C.A.; Yoshida, T.M.; Twary, S.N.; Teshima, M.; Alvarez, M.A.; Zidenga, T.; Heikoop, J.; Perkins, G.; Rahn, T.A.; et al. Oil and gas produced water as a growth medium for microalgae cultivation: A review and feasibility analysis. Algal Res. 2017, 24, 492–504.

- Atoufi, H.D.; Lampert, D.J. Impacts of oil and gas production on contaminant levels in sediments. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2020, 6, 43–53.

- Igunnu, E.T.; Chen, G.Z. Produced water treatment technologies. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2014, 9, 157–177.

- Dórea, H.S.; Bispo, J.R.; Aragão, K.A.; Cunha, B.B.; Navickiene, S.; Alves, J.P.; Romão, L.P.; Garcia, C.A. Analysis of BTEX, PAHs and metals in the oilfield produced water in the State of Sergipe, Brazil. Microchem. J. 2007, 85, 234–238.

- Baca, S.R.; Kupfer, A.; McLain, S. Analysis of the Relationship between Current Regulatory and Legal Frameworks and the “Produced Water Act”; NM WRRI Technical Completion Report No. 396; New Mexico Water Resources Research Institute: Las Cruces, NM, USA, 2021.

- Clark, C.E.; Veil, J.A. Produced Water Volumes and Management Practices in the United States; Argonne National Lab. (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 2009.

- Winckelmann, D.; Bleeke, F.; Thomas, B.; Elle, C.; Klöck, G. Open pond cultures of indigenous algae grown on non-arable land in an arid desert using wastewater. Int. Aquat. Res. 2015, 7, 221–233.

- Operation, N.G. Qatar Petroleum. State of Qatar. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Doha, Qatar, 19–22 January 2014.

- Bhadja, P.; Kundu, R. Status of the Seawater Quality at Few Industrially Important Coasts of Gujarat (India) off Arabian Sea; NISCAIR-CSIR: New Delhi, India, 2012.

- Tibbetts, P.; Buchanan, I.; Gawel, L.; Large, R. A comprehensive determination of produced water composition. In Produced Water; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 97–112.

- Nasiri, M.; Jafari, I. Produced water from oil-gas plants: A short review on challenges and opportunities. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 2017, 61, 73–81.

- Fillo, J.P.; Koraido, S.M.; Evans, J.M. Sources, characteristics, and management of produced waters from natural gas production and storage operations. In Produced Water: Technological/Environmental Issues and Solutions; Ray, J.P., Engelhardt, F.R., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 151–161.

- Abdel-Raouf, N.; Al-Homaidan, A.; Ibraheem, I. Microalgae and wastewater treatment. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 19, 257–275.

- Arbib, Z.; Ruiz, J.; Álvarez-Díaz, P.; Garrido-Perez, C.; Perales, J.A. Capability of different microalgae species for phytoremediation processes: Wastewater tertiary treatment, CO2 bio-fixation and low cost biofuels production. Water Res. 2014, 49, 465–474.

- Åkerström, A.M.; Mortensen, L.M.; Rusten, B.; Gislerød, H.R. Biomass production and nutrient removal by Chlorella sas affected by sludge liquor concentration. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 144, 118–124.

- Mohamad, S.; Fares, A.; Judd, S.; Bhosale, R.; Kumar, A.; Gosh, U.; Khreisheh, M. Advanced Wastewater Treatment Using Microalgae: Effect of Temperature on Removal of Nutrients and Organic Carbon. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Environment and Industrial Innovation, Kuala Lampur, Malaysia, 28–30 April 2017; Volume 67, p. 012032.

- Gao, F.; Peng, Y.-Y.; Li, C.; Yang, G.-J.; Deng, Y.-B.; Xue, B.; Guo, Y.-M. Simultaneous nutrient removal and biomass/lipid production by Chlorella sin seafood processing wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640–641, 943–953.

- Almomani, F.; Judd, S.; Shurair, M. Potential use of mixed indigenous microalgae for carbon dioxide bio-fixation and advanced wastewater treatment. In 2017 Spring Meeting and 13th Global Congress on Process Safety; AIChE: New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- Sivakumar, G.; Xu, J.; Thompson, R.W.; Yang, Y.; Randol-Smith, P.; Weathers, P.J. Integrated green algal technology for bioremediation and biofuel. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 107, 1–9.

- Davis, R.E.; Fishman, D.B.; Frank, E.D.; Johnson, M.C.; Jones, S.B.; Kinchin, C.M.; Skaggs, R.L.; Venteris, E.R.; Wigmosta, M.S. Integrated evaluation of cost, emissions, and resource potential for algal biofuels at the national scale. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 6035–6042.

- Ventura, J.-R.S.; Yang, B.; Lee, Y.-W.; Lee, K.; Jahng, D. Life cycle analyses of CO2, energy, and cost for four different routes of microalgal bioenergy conversion. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 137, 302–310.

- Kang, Z.; Kim, B.-H.; Ramanan, R.; Choi, J.-E.; Yang, J.-W.; Oh, H.-M.; Kim, H.-S. A cost analysis of microalgal biomass and biodiesel production in open raceways treating municipal wastewater and under optimum light wavelength. J. Microbiol. BioTechnol. 2015, 25, 109–118.

- Judd, S.; Al Momani, F.; Znad, H.; Al Ketife, A. The cost benefit of algal technology for combined CO2 mitigation and nutrient abatement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71 (Suppl. C), 379–387.

- Talebi, A.F.; Dastgheib, S.M.M.; Tirandaz, H.; Ghafari, A.; Alaie, E.; Tabatabaei, M. Enhanced algal-based treatment of petroleum produced water and biodiesel production. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 47001–47009.

- Parsy, A.; Sambusiti, C.; Baldoni-Andrey, P.; Elan, T.; Périé, F. Cultivation of Nannochloropsis oculata in saline oil & gas wastewater supplemented with anaerobic digestion effluent as nutrient source. Algal Res. 2020, 50, 101966.

- Takáčová, A.; Smolinská, M.; Semerád, M.; Matúš, P. Degradation of btex by microalgae Parachlorella kessleri. Petrol. Coal 2015, 57, 101–107.

- Abdelsalam, E.; Kafiah, F.; Tawalbeh, M.; Almomani, F.; Azzam, A.; Alzoubi, I.; Alkasrawi, M. Performance analysis of hybrid solar chimney–power plant for power production and seawater desalination: A sustainable approach. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 17327–17341.

- Das, S.K.; Sathish, A.; Stanley, J. Production of biofuel and bioplastic from Chlorella Pyrenoidosa. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 16774–16781.

- Wilson, M.H.; Shea, A.; Groppo, J.; Crofcheck, C.; Quiroz, D.; Quinn, J.C.; Crocker, M. Algae-based beneficial re-use of carbon emissions using a novel photobioreactor: A techno-economic and life cycle analysis. BioEnergy Res. 2020, 14, 292–302.

- Rafiee, P.; Ebrahimi, S.; Hosseini, M.; Tong, Y.W. Characterization of soluble algal products (SAPs) after electrocoagulation of a mixed algal culture. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 25, e00433.

- Hopkins, T.C.; Graham, E.J.S.; Schuler, A.J. Biomass and lipid productivity of Dunaliella tertiolecta in a produced water-based medium over a range of salinities. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 3349–3358.

- Hopkins, T.C.; Graham, E.J.S.; Schwilling, J.; Ingram, S.; Gómez, S.M.; Schuler, A.J. Effects of salinity and nitrogen source on growth and lipid production for a wild algal polyculture in produced water media. Algal Res. 2019, 38, 101406.

- Karatay, S.E.; Dönmez, G. Microbial oil production from thermophile cyanobacteria for biodiesel production. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3632–3635.

- Das, P.; Abdulquadir, M.; Thaher, M.; Khan, S.; Chaudhary, A.K.; Alghasal, G.; Al-Jabri, H.M.S.J. Microalgal bioremediation of petroleum-derived low salinity and low pH produced water. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 435–444.

- Ranjbar, S.; Quaranta, J.; Tehrani, R.; Van Aken, B. Algae-based treatment of hydraulic fracturing produced water: Metal removal and biodiesel production by the halophilic microalgae Dunaliella salina. In Bioremediation and Sustainable Environmental Technologies. In Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Bioremediation and Sustainable Environmental Technologies, Miami, FL, USA, 18–21 May 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015.