Queen Helen Nemanjić (?–Brnjaci near Zubin Potok, February 8, 1314) was a Serbian medieval queen and consort of King Stefan Uroš I (r. 1243–1276), the fifth ruler of the Serbian Nemanide dynasty. She was the mother of the kings Stefan Dragutin and Stefan Uroš II Milutin. Today, she is known as Helen of Anjou (Jelena Anžujska in Serbian) although her real name was most probably Heleni Angelina (Ελένη ΑAγγελίνα). She was the founder of the Serbian Orthodox monastery of Gradac as well as four Franciscan abbeys in Kotor, Bar, Ulcinj, and Shkodër. Together with her sons, Kings Stefan Dragutin and Stefan Uroš II Milutin she helpedrenovation of Benedictine abbey of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus near Shkodër on Boyana river in present-day Albania. After the death of her husband, she ruled Zeta and Travunija until 1306. She was known for her religious tolerance and charitable and educational endeavors. She was elevated to sainthood by the Serbian Orthodox Church. Along with Empress Helen, the wife of Serbian Emperor Stefan Uroš IV Dušan, Queen Helen was the most frequently painted woman of Serbian medieval art. Six of her portraits can be found in the monumental painting ensembles of the Serbian medieval monasteries of Sopoćani, Gradac, Arilje, Đurđevi Stupovi (Pillars of St. George), and Gračanica, as well as on two icons and one seal. Queen Helen is also the only female Serbian medieval ruler whose vita was included in the famous collection of the "“Lives of Serbian Kings and Archbishops"” by Archbishop Danilo II, a prominent church leader, warrior, and writer.

- Helen of Anjou

- Nemanide dynasty

- Sopoćani Monastery

- Gradac Monastery

- Queen Helen’s seal

- Vatican icon

- Gračanica Monastery.

1. Introduction

Queen Helen is popularly known as Helen of Anjou. This identification is based on the statement of her biographer, Archbishop Danilo II, who, as her contemporary, interlocutor, and admirer, writes that Helen was of French origin. Queen Helen was indeed, in the charters of Charles I and Charles II of Anjou, kings of Sicily and Naples, called a dear cousin – consanguinea nostra carissima

[1] (p. 46). There is proof that Helen's sister Maria was married to Anselm de Keu (in some documents also spelled as de Chau), Captain General of Charles I of Anjou in Albania. However, based on the latest research, Helen's origins are connected with the French and Hungarian nobility in Slavonia and Srem. In 1984, Gordon McDaniel made a very convincing case that Helen and Maria were daughters of the Hungarian nobleman, ruler of Srem and Count of Kovin, John Angelos (Ἰωάννης Ἄγγελος) also known as Good John (Καλοϊωάννης), the son of the Byzantine Emperor Isaac II and the French Matildis Vianden of Posaga (Požega), granddaughter of Peter II Courtenay, the Latin ruler of Constantinople [1] (p. 43). This assumption is still valid today and according to the most recent research, it reflects the very complex political relations between Byzantium, Hungary, and Serbia around the mid-13th century [2] (p. 53).

Princess Heleni Angelina married the Serbian king Stefan Uroš I Nemanjić (r. 1243–1276) probably in mid1250. They had three children: two sons, subsequently kings, Stefan Uroš Dragutin (r. 1276–1282) and Stefan Uroš II Milutin (r. 1282–1321), and one daughter, Brnj(a)ča (Berenice). Recently, during the excavation of the Church of the Holy Virgin in the Studenica Monastery, the mausoleum of the first generations of the Nemanide family, an intriguing yet still not completely explained tombstone – built into the floor alongside the tomb of St. Symeon (Stefan Nemanja)—was found. Its inscription reads: +СТѢФАНЬ СІНЬКРАЛІАУРОША УНОУКЬСТГОСИМОНАМНАХА ИПРАУНОУКЬСТГО СИМЕϖНА [+Stefan, son of King Uroš, grandson of Saint Simon the Monk (Stefan the First-crowned), great-grandson of Saint Symeon]. The bones of the two-year-old boy were found in the grave below the tombstone. Because of the inscription, the location of the tomb, and the fact that the buried person bore the name Stefan, it is assumed that the mentioned person was the first child of Queen Helen and King Uroš I [3] (p. 94). If this is to be accepted, Prince Stefan was born and passed away a few years before the birth of his brother Stefan Dragutin (born around 1250) [4] (p. 11).

In 1276, a conflict broke out between Queen Helen’s husband Uroš I and their eldest son Stefan Uroš Dragutin. King Uroš I abdicated, and less than two years later died in Hum. He was buried in his endowment, the Sopoćani Monastery. During the reign of her sons, Stefan Uroš Dragutin (r. 1276–1282) and Stefan Uroš II Milutin (r. 1282–1321) Queen Helen maintained provincial administration in the Zeta and Travunija until 1306 [5] (p. 357). Travunija (Latin Tribunia) was a South Slavic medieval principality that was part of medieval Serbia (850–1355). Travunija stretched from the city of Dubrovnik to the Bay of Kotor. It bordered Zahumlje in the northwest and Duklja in the southeast. During the second part of the 12th century, Travunija was fully incorporated into the united Serbian medieval states (Raška and Zeta) under the rule of the Nemanide dynasty. From that time onTravunija existed as a semi-separate principality within the Serbian lands. Under the same name, sometimes also called the Trebigne of the Ragusans, this region belonged to the Serbian medieval kingdom, later empire, until 1355.

In Zeta (present-day Montenegro) and Travunija, Queen Helen had her own army and chancellery. She proved to be a very successful administrator, governing regions with a mixed Serbian Orthodox and Roman Catholic population. She helped renovation of four Franciscan abbeys in Kotor, Bar, Ulcinj, and Shkodër (present-day Albania). Together with her sons, Kings Dragutin and Milutin, she also helped the renovation of the Benedictine abbey of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus on Boyana river. Today, the church is almost destroyed, but the inscription, written in Latin and kept today at the Historical Museum in Shkodër, testifies to their ktetorship. Queen Helen became a nun around 1295 in the Church of St. Nicholas in Shkodër. She died at her court in Brnjaci on 8 February 1314. She was canonized by the Serbian Orthodox Church three years later. Even though her feast day is still celebrated on November 12 (October 30), some authors are questioning her conversion to Orthodoxy [6] (pp. 104–106).

2. The Sopoćani Monastery

2. The Sopoćani Monastery

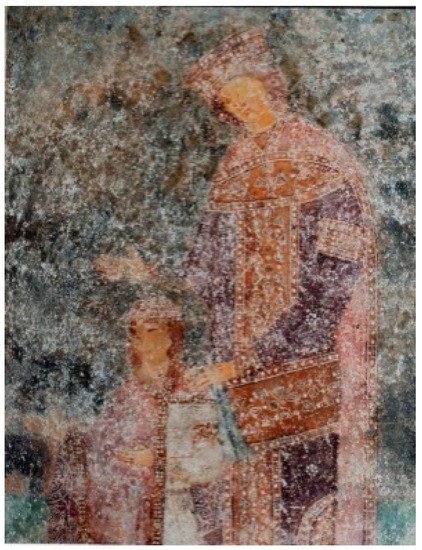

Painted between 1263 -–1268 [7] (p. 18), the figure of Queen Helen appears twice in the Holy Trinity Church of the Sopoćani Monastery, the endowment of King Stefan Uroš I, built from 1259 to 1270, near the source of the Raška River in the region of Ras, the center of the Serbian medieval state, located 15 km west of the present-day town of Novi Pazar. In the narthex, King Stefan Uroš I’s royal family is shown standing in front of the Mother of God with Christ. King Stefan Uroš I is depicted with their eldest son, Stefan Dragutin, heir to the throne, on the southern part of the eastern wall of the narthex, while Queen Helen is shown behind him, on the southern wall, with their younger son, Stefan Uroš II Milutin (Figure 1). From an iconographical point of view, this is not a founder’s composition but a portrait of the royal family, which is the first of its kind in Serbian medieval painting. Helen is shown as a tall, beautiful young woman with a crown on her head. She is dressed in the Byzantine manner, in a purple divitision (διβητήσιoν) decorated with a wide collar—a maniakon (μᾰνῐᾰ́κќῐον). On the front, the dress is decorated with a loros (λῶρος)—a wide decorated ribbon wound around the torso so that one end hung down in front and and the other hung over the right arm. The loros is decorated with precious stones and pearl wreaths. On the side of the dress there is a circular decoration—rota—a motif that dates back to Antiquity. Queen Helen is wearing a simple and open crown—a stemma (στέμμα).

Figure 1.

Queen Helen with Prince Stefan Uroš II Milutin, fresco, 1263–1268, Holy Trinity Church of Sopoćani Monastery, southeast corner of the narthex, first zone. Photo by Srđan Vulović, courtesy of the National Museum of Kraljevo.

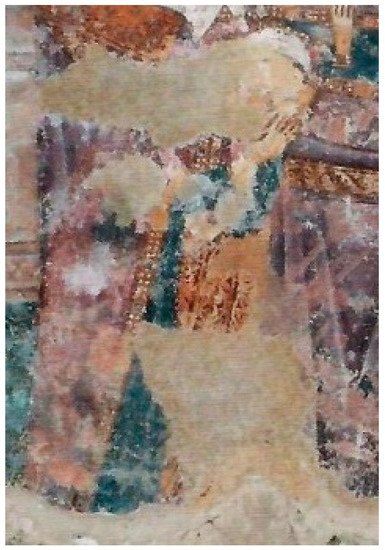

In the first zone of the northern wall in the narthex of the Holy Trinity Church of Sopoćani Monastery, a historical scene from the life of the Nemanide royal family is represented—the death of Queen Anne Dandolo, mother of King Stefan Uroš I (Figure 2) [8] (pp. 24–25). The composition is modeled after the scene of the Dormition of the Mother of God and shows the mourning of Queen Anne. This time, Queen Helen is depicted in the foreground, kneeling in front of the scaffolding, and resting her cheek on her mother-in-law's hand. She wears a dark blue dress with a purple trimmed cloak and a white scarf on her head. Representations of hour of death of historical figures are extremely rare in Serbian medieval painting and can be found only later in the monasteries of Gračanica and the Patriarchate of Peć [9] (pp. 99–127).

Figure 2.

Death of

3. The Gradac Monastery

Queen Anne Dandolo. Queen Helen kneeling in front of the scaffolding (detail), 1263–1268. Holy Trinity Church of Sopoćani Monastery, northern wall of the narthex, first zone. Photo by Srđan Vulović, courtesy of the National Museum of Kraljevo.

3. The Gradac Monastery

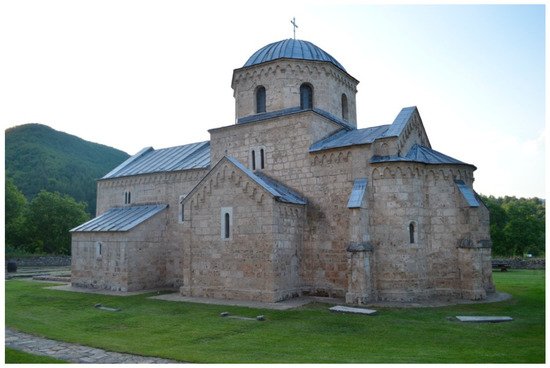

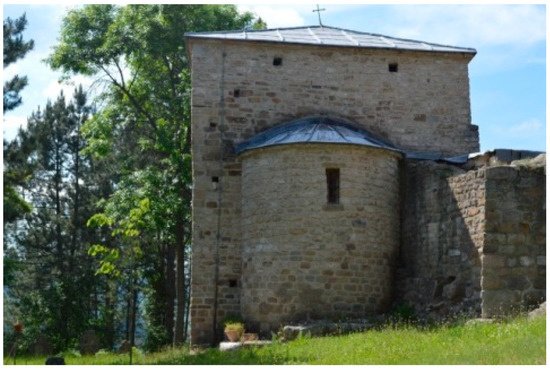

Queen Helen is is depictedepicted in the Church of the Annunciation at the Monastery of Gradac. The Annunciation Church of the Gradac Monastery (Figure 3) was her endowment, built around 1275 on the elevated plateau above the Gradačka river at the edge of the forested slopes of Mt. Golija, 12 km to the west of the medieval fortress of Brvenik. Although the overall ensemble of the wall paintings of the Gradac Monastery was largely damaged, a founder’s composition was once depicted on the south wall of the western part of the nave, above a double tomb [10] (p. 81). It is still possible to distinguish several figures from the outlines: the Mother of God presents a monk to the enthroned Christ, followed by King Stefan Uroš I and Queen Helen. Together they are holding a model of the church (Figure 4). Queen Helen is represented in a full-frontal position, usually reserved only for Byzantine emperors [8] (p. 28), which led Danica Popović to the conclusion that she was the first founder [10] (p. 85). The fresco was largely destroyed and today is mostly unrecognizable. However, it is possible to see that Helen is wearing an open crown on her head. Traces of a halo around her head are also visible.

Figure 3. Annunciation Church of Gradac Monastery, endowment of Queen Helen, built around 1275. Photo Čedomila Marinković.

Figure 4.

4. Queen Helen’s Royal Seal

Queen Helen, first to the right, holding a model of a church together with her husband, King Uroš I. Ktetor’s composition, Annunciation Church of Gradac Monastery, south wall of the nave, around 1275. Photo Čedomila Marinković.

4. Queen Helen’s Royal Seal

One letter by Queen Helen—addressed to Prince Ivan Storlat of Dubrovnik and Archbishop Alijard, dated October 28 without the year, and sealed with her royal seal—has been preserved to the present day. The dating of the letter to which the seal was attached is still an open question in Serbian medieval sigillography, but according to the latest literature, it was probably written after 1278. The seal is 4.7 cm in diameter and is made of pure wax (Figure 5). Its copy is nowadays kept in the Collection of Seal Replicas of the National Museum in Kraljevo. It shows the figure of Queen Helen wrapped in a cloak, sitting on a pillow placed on a plain chair, which has no arm or backrest. A flat crown without any details is placed on her head. The inscription, which runs around the depiction reads: СЛѢНА КРАЛІЦА.Б(ЛА)ГОЧУ(ЕС)ТИВЬ.СП.ЗЕ(МЛ). ⦋Gl(ori)ous queen, pious… srb… l(and)⦌ [11] (p. 56).

Figure 5. Queen Helen represented as a ruler. Replica of the wax seal, Collection of Seal Replicas No. 133. National Museum in Kraljevo. Photo by Srđan Vulović, courtesy of the National Museum of Kraljevo.

5. The Monastery of Đurđevi Stupovi (Pillars of St. George), Chapel of King Dragutin

5. The Monastery of Đurđevi Stupovi (Pillars of St. George), Chapel of King Dragutin

The Monastery of Đurđevi Stupovi (Pillars of St. George—pillar being called stolp, in Old Church Slavonic) was erected in about 1170 as an endowment of Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja and dedicated to St. George. The monastery is located near the present-day town of Novi Pazar in the Serbian region of Ras, on the top of a prominent elevation covered with forest. The monastery complex consisted of the Church of Saint George, dining room, refectory, water tanks, and walls around the entrance tower. After the additional construction of apses in the east side in 1282–1283, the entrance tower was turned into a chapel that King Dragutin designed for his tomb (Figure 6). The inside of the chapel is covered in frescos with historical content. Another founder’s composition was depicted there. On the south wall of the chapel, a procession of Nemanide monks is approaching Christ on the throne: Symeon Nemanja, Stefan the First-crowned as the monk Simon, King Uroš as the monk Symeon, and Queen Helen. For the first time in Serbian 13th century iconography, a procession of patron saints, i.e., the Horizontal genealogy oHorizontal genealogy of the Nemanide f the Nemanide family is interrupted, and the founder of the church is represented not after his saintly predecessors but on the other, western wall. Queen Helen (Figure 7) is depicted wearing a monastic habit and a white veil, either as a novice or as sign of mourning, and a halo around her head. On the left side, next to her head, is an inscription that reads: ІIЄЛѢНА ВЕЛИКА КРАЛІЦА ⦋HA BEЛИKA KPAЛIЦA [Helen, the great queen⦌].

Figure 6. Entrance tower of Monastery of Đurđevi Stupovi turned into the tomb chapel of King Dragutin, around 1282. Photo Čedomila Marinković.

Figure 7. Queen Helen as a widow or novice, procession of Nemanide-monks, after 1282–1283, Monastery of St. George’s Pillars, Chapel of King Dragutin, south wall. Photo Nenad Vukićević, Blago Fund, Inc.

6. Church of St. Achillius in Arilje

6. Church of St. Achillius in Arilje

The Church of St. Achillius is located in the center of the town of Arilje in western Serbia. It was built as the main endowment of King Dragutin, Queen’s Helen elder son. According to the preserved inscription, the church was painted around 1295/97 [12] (p. 95), i.e., fifteen years after King Dragutin abdicated in favor of his younger brother Milutin in 1282. Queen Helen is depicted on the south wall of the nave at the back of the Nemanide procession, led before Christ by Stefan the First-crowned as the monk Simon, followed by King Uroš I as the monk Symeon. She is painted wearing a monastic habit (Figure 8) with a halo around her head and an inscription on both sides of the figure that reads: ІIЄЛЄНА КРАЛІЦА ВЬСЄ СРЬСКІЄ ЗЕМЛЄ ⦋HA KPAЛIЦA BЬCЄ CPЬCKIЄ 3EMЛЄ [Helen, the queen of all Serbian lands⦌]. Common belief has it that the reign of Dragutin lasted from 1276 to 1282. Recently, this was questioned by Vlada Stanković who assumes that instead of the brothers and their mother reigning separately, there was a “peculiar (ruling) triumvirate” of King Dragutin, Milutin, and Queen Helen that lasted from the abdication of King Uroš I in 1276 to Milutin’s peace agreement with the Byzantines in 1299 [2] (p. 69). This fact could better explain the appearance of Queen Helen in Arilje, as well as the inscription surrounding her head.

Figure 8.

7. Icons

Queen Helen as a nun, procession of Nemanide monks, 1295–1297, Church of St. Achillius in Arilje, south wall of the nave. Photo Nenad Vukićević, Blago Fund, Inc.

7.Icons

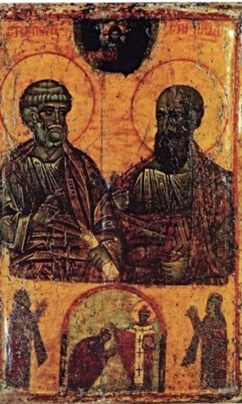

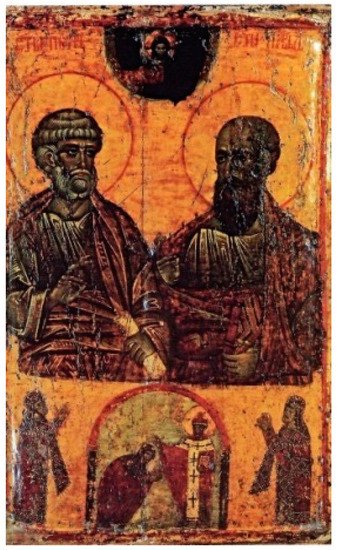

Queen Helen is also associated with two icons that were donated to churches in Italy. The first icon is that of Sts. Peter and Paul, which is kept in the Vatican Treasury in Rome, and the second icon is that of St. Nicholaswhich was donated to his church in Bari.

The Vatican icon was painted on poplar wood in egg tempera on a gold background. It is divided into two separate registers by a horizontal red line. The upper part of the icon shows the busts of the apostles St. Peter and St. Paul who are depicted in a gesture of blessing (Figure 9). Peter is holding a scroll and Paul a book of his epistles. They occupy two thirds of the composition and above them is the bust of Christ. The lower third of the icon is intended for the founders. In the central part, below the arcade on the pillars, Queen Helen is represented as a nun bowing before a Western bishop with a nimbus, holding a book and the episcopal staff (crozier), who is blessing her. The bishop is dressed in a green tunic and red chasuble, and a miter on his head. The sides of the composition are occupied by two figures identically dressed in the Byzantine costume and with crowns, their heads in a posture of prayer: her sons Dragutin on the left and Milutin on the right. This icon of St. Peter and St. Paul was probably commissioned by Queen Helen and was presumably given to Pope Nicholas IV (r. 1288–1299). According to Mihailović–Shipley [13] (pp. 92–93) the icon holds an important message. As the commissioner of the work, Queen Helen was probably aware that the contemporary religious politics in the region corresponded with the idea of the unification of the two churches promoted by the popes in the 13th century, and even briefly achieved in the Lyon Union. As it is well known, the cult of St. Peter and St. Paul was established in the late 4th century, when Pope Damascus consistently promoted them as emblems of unity within the church [14] (p. 102). During the pontificate of Nicholas IV (r. 1288–92) this idea continued to be promoted through the images of Sts. Peter and Paul [13] (pp. 94).

Figure 9.

8. The Gračanica Monastery

Queen Helen as a nun flanked by her sons, Dragutin and Milutin, Sts. Peter and Paul icon around 1282, 74 × 49 cm. (copyist: Z. Živković). The Gallery of Frescoes, Belgrade. Inv. No. 870. Photo courtesy of The Gallery of Frescoes, Belgrade.

Although the second icon that Queen Helen donated to the Church of St. Nicholas in Bari has not been preserved, there is a description of it in the work of Antonio Beatillo from 1620 [15] (p. 653 ). The height of the icon was less than one meter and the width was about half a meter. However, we learn that the panel from the Vatican Treasury reveals many similarities with this one. The representation consisted of the bust of St. Nicholas in the upper part of the icon and three kneeling figures with Latin inscriptions at the bottom: King Dragutin was represented on the left as REX STEPHANUS FILIUS UROSII REGIS SERVIAE, [King Stefan son of Uroš the ruler of Serbia], King Milutin on the right - REX UROSIUS FILIUS UROSII REGIS SERVIAE [King Uroš (II) son of Uroš (I) the ruler of Serbia], and Queen Helen in the middle whose figure was accompanied by a long inscription: MEMENTO FAMULE TUE HELEN DEI GRATIA REGINE SERVIAE UXORIS MAGNI REGIS UROSII ET MATRIS URSII ET STEPHANI SUPRASCRIPTORUM REGUM. HANC YCONAM AD HONOREM SANCTI NICOLAI ORDINAVIT [Oh, Lord, remember Thy servant in the Grace of God, Helen the Queen of Serbia, wife of the great King Uroš (I) and mother of Uroš (II) and Stefan, the above signed rulers, who commissioned this icon in honor of St. Nicholas] [16] (p. 143). With these icons and adopting a recognizable Italian style, Queen Helen may have wished to promote the Serbian Kingdom as a multicultural state, with strong Italian connections and affinities or to have the icon appeal stylistically to its intended Catholic audience.

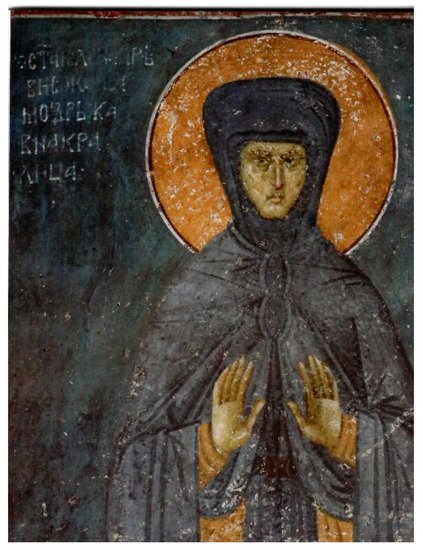

8. The Gračanica Monastery

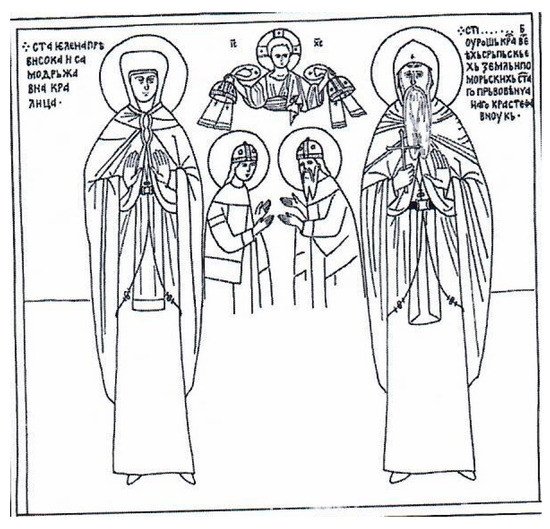

The Gračanica Monastery is one of King Stefan Uroš II Milutin's last monumental endowments. The monastery is located in Gračanica, Kosovo, about 5 km from Priština, and represents one of the masterpieces of Serbian medieval art and architecture. On the northern part of the eastern wall in the narthex of the Annunciation Church of the Gračanica Monastery, painted around 1321, in the first zone to the right Queen Helen, is represented as a saint with a halo and the inscription: СТА IEЛEНA ПРЕВИСОКА САМОДРЬЖАВНА КРАЛИЦА ⦋St. Helen the great independent queen⦌ (Figure 10). Next to her, to the right, there is a frontal representation of a male person dressed in a monk’s suit with a halo and the visible inscription that reads: СТИ СТЕФАНЬ ОУРОШЬ КРАЛ ВСѢХЬ СРЬПСКИХ ЗЕМЛЬ И ПОМОРСКИХЬ СТАГО ПРЬВОВѢNЧААNАГО КРАЛА СТ (…) ВNОУКЬ ⦋St. Stefan Uroš King of all Serbian lands and the Littoral, St. King Stefan the First-crowned St (.) grandson] [17] (p. 107). Above them, there is a representation of Christ Emanuel, giving them a monastic insignia. Although data from the image and from the inscription are mutually exclusive—King Milutin did not become a monk during his lifetime—according to Branislav Todić’s first interpretation, this scene represents “the symbolic monasticism of King Milutin” [17] (p. 76) and was created a couple of years later than the original decorative program of the Gračanica church, probably around 1324 [17] (p. 130). In an article published five years later, the same author corrected his reading of the inscription and interpreted the scene as a representation of Queen Helen as a nun and King Uroš I as a monk [18] (pp. 13). The iconography of the scene and its further political message is, however, unique. During a closer inspection of the fresco between the representations of St. Helen and Uroš, the remains of two figures were discovered (Figure 11). Their appearance, although only in the drawing, as well as the fact that Christ provided them with two identical, domed crowns, according to various authors simplifies their recognition. Reduced in size compared to the monk Symeon and St. Helen, two figures of different ages are presented here, facing each other, prayerfully bowed and with their hands in the same gesture, both having domed crowns and halos around their heads. On the elderly person, next to Uroš, there is a maniakion and a loros falling over his left arm. According to Todić, this king was identified with King Milutin because of his long beard, while the person across from him, a young beardless man wearing a tunic and a cloak was seen “as his son Constantine” [18] (p. 14). Recently, Dragan Vojvodić proposed another identification of these figures. He saw them as a young king Stefan Uroš IV Dušan and his father Stefan III Dečanski, who have been consciously omitted from the original program of Gračanica because of the well-known conflict between Stefan Dečanski and King Milutin in 1314. Additionally, Stefan Uroš IV Dušan and his father Stefan III Dečanski were painted in Gračanica after their coronation on 6 January 1322 [19] (p. 262). The originally imagined painting of the Gračanica narthex thus intended to legitimate the ascension to the power of Stefan Dečanski and his fellow ruler in the presence of St. Helen and Uroš I as a monk.

Figure 10. Queen Helen as a nun, 1322, Church of the Annunciation of the Gračanica Monastery, eastern wall. Photo by Srđan Vulović, courtesy of the National Museum of Kraljevo.

Figure 11.

Niš

Byzantium.

9. Conclusion

Summarizing the general lines of Queen Helen’s iconography, we can conclude that among an extraordinary number of her representations, several innovations were introduced. From an iconographical point of view, it is interesting that she is shown in several roles: as a young queen, she was represented in secular family portraits and historical scenes first introduced in Serbian medieval iconography in Sopoćani; as co-ruler in her ktetor's (founder’s) portrait (as in the Gradac monastery); as the independent ruler on one preserved seal; as the only woman in the horizontal genealogy of Nemanide family in the endowments of her son; and as a nun before the Roman Catholic authorities on the icons in the Vatican and in Bari.

One can single out several periods in her representations and several messages behind them. From her representation on the seal and icons, but especially from the inscriptions written next to her figure in her portraits from the Monastery of Đurđevi Stupovi, it is pointed out that she was great, pious queen. A strong visual stress of the piousness of Queen Helen is underlined in various ways in her visual renderings: she is represented as a widow in Đurđevi stupovi and with a halo in all her representations—from the ktetor’s portrait in Gradac to her portrait in Gračanica. If we understand the halo as a sign of sanctity, these representations of Queen Helen were not very much in tune with historical events, as she was canonized in 1317, three years after her death. Queen Helen appears represented with a halo already in her (today much damaged) donor's portrait in the Bogorodica Bistrička church painted around 1250. The halo depicted around the heads of living persons, thus represents their highest dignity. In Serbian royal iconography, such halos were not represented before the portraits painted around 1230 in the south parekklesion of the Holy Virgin’s church in the Monastery of Studenica ⦋20⦌ (p. 162).

In the aforementioned church of Bogorodica Bistrička, both King Uroš I and Queen Helen are represented, wearing full Byzantine costumes and crowns as a symbol of power. Of course, there was not any legal ground for that behavior and Byzantium never approved it but could not do very much except to resent or reconcile it [20] (pp. 170–171).

On the other hand, the frequently mentioned title of Queen Helen as ruler of all Serbian lands reflects the political reality of her status after the death of her husband King Uroš I, when she acquired the littoral lands from Trebinje to Shkodër and territories around Plav, the Upper Lim River, and Brnjaci. These domina regina mater, together with the old and developed littoral cities such as Kotor, Bar, Ulcinj, and Shkodër became at that time the main artery of the economy and trade, and Queen Helen remained in memory as a wise and capable female ruler who loved tradition, joined cultures, and helped those in need.

The overall imagery of Queen Helen corresponding to the place where it was shown was conveyed different and complex messages. In the case of the two icons the message corresponds with the ongoing contemporary dialogue between East and West at the time of the still existing idea regarding the unification of the two churches. It is evident that Queen Helen deeply understood the position of her dominion, placed between two strong influences and acted in it either as a “queen on a chess board,” constructing a “diplomatic game” [13] (p. 118), or as a politician proceeding in a “Realpolitik” manner ⦋6⦌ (p. 105). Being the Queen of an Orthodox society, at the same time, she represented an axis, from which the political powers of her two sons (at least till 1301) were suspended [13] (p. 118). Aftermost her authority as a saint helped her descendants, Kings Stefan Uroš III Dečanski and his son, Stefan Uroš IV Dušan, conveying a message of legitimization of the succession to the throne of Serbia.

To summarize: In lands ruled by Queen Helen, the cohabitation and interaction of populations of both Orthodox and Catholic affiliation were very common, in particular in the Littoral, as the area of direct contact. Hence, the visual culture of her era has preserved examples of all the various guises of her identity and the different political, religious, and social roles and duties she performed.

9. Conclusions

References

- McDaniel, G.L. On Hungarian–Serbian Relations in the Thirteenth Century: John Angelos and Queen Jelena. Ungarn Jahrbuch 1982–1983, 12, 43–50.

- Stanković, V. Kralj Milutin (1282–1321) (King Milutin (1282–1321); Freska: Beograd, Serbia, 2012.

- Ječmenica, D. Nemanjići drugog reda (The Second-Rate Nemanides); Filozofski Fakultet: Beograd, Serbia, 2018.

- Ćirković, S. Kralj Stefan Dragutin (King Stefan Dragutin). Račanski Zbornik 1997, 3, 11–20.

- Bubalo, Đ. Jelena kraljica (Helen the queen). In Srpski biografski rečnik (Serbian Biographical Dictioannary); Popov, Č., Ed.; Matica Srpska: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2009; Volume 4, pp. 357–358.

- Erdeljan, J. Two inscriptions from the church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus near Shkodër and the question of text and image as markers of identity in Medieval Serbia. In Texts/Inscriptions/Images; Moutafov, E., Erdeljan, J., Eds.; National History Museum: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2017; pp. 97–110.

- Komatina, I. Ana Dandolo-prva srpska kraljica? (Anne Dandolo, the First Serbian Queen?). ZMSI 2014, 89, 7–22.

- Radojčić, S. Portreti srpskih vladara u srednjem veku (Portraits of Serbian Rulers in the Middle Ages), 2nd ed.; Republički Zavod Za Zaštitu Spomenika Kulture: Beograd, Serbia, 1997.

- Đurić, J.V. Istorijske kompozicije u srpskom slikarstvu srednjeg veka (Historical composition in Serbian medieval painting). ZRVI 1968, 11, 99–127.

- Popović, D. Srpski vladarski grob usrednjem veku, (Serbian Roayal Tomb in the Middle Ages); Institut Za Istoriju Umetnosti: Beograd, Serbia, 1992.

- Kopije pečata sa povelja srpskih vladara i vlastele XIII–XIV veka (Copies of Seals from the Charters of Serbian Rulers and Nobility of the XIII-XIV Century); Kulić, R. (Ed.) Zbirka Galerije Matice Srpske: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2009.

- Natpisi istorijske sadržine u zidnom slikarstvu (Inscriptions of Historical Content in Wall Painting); Subotić, G.; Miljković, B.; Špadijer, I.; Toth, I. (Eds.) Vizantološki Institute SANU: Beograd, Serbia, 2015.

- Mihailović-Shipley, M. Un Unexpected Image of Diplomacy in a Vatican Panel. In Byzantium in Eastern European Culture in the Late Middle Ages; Rossi, M.A., Sullivan, A.I., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 91–118.

- Dal Santo, G.L. Concordia Apostolorum—Concordia Augustorum: Building a Corporate Image for the Theodosian Dynasty. In East and West in the Roman Empire of the Fourth Century: An End to Unity? Dijkstra, R., Van Poppel, S., Slootjes, D., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 164–179.

- Da Bari Beatillo, A. Historia della vita, miracoli, traslatione e gloria dell’illustrissimo Confessore di Christo, San Nicolò il Magno, arcivescovo di Mira, patrono e protettore della città di Bari, Naples and Palermo; Stamperia di Pietro Coppola: Palermo, Italia, 1642.

- Subotić, G. Kraljica Jelena Anžujska, ktitor crkvenih spomenika u Primorju, (Queen Helen d’Anjou, Founder of Church Monuments in Primorje). Istorijski Glasnik 1958, 1–2, 131–148.

- Todić, B. Gračanica, slikarstvo (Gračanica, Paintings); Prosveta: Beograd, Serbia; Jedinstvo: Priština, Serbia, 1988.

- Todić, B. Kralj Milutin sa sinom Konstantinom i roditeljima monasima na fresci u Gračanici (King Milutin with his son Konstantin and his parents, monks on the fresco in Gračanica). Saopštenja 1993, XXV, 7–23.

- Vojvodić, D. Doslikani vladarski portrti u Gračanici (Additionaly painted portraits of rulers in Gračanica). Niš i Vizantija 2009, VII, 251–265.

- Popović, B. Srpska srednjovekovna vladarska i vlasteoska odežda (Serbian Medieval Royal and Nobility Costume), 2nd ed.; Muzej Srpske Pravoslavne Crkve: Beograd, Serbia, 2021.