The length and number of areas with positive margins of resection have been correlated with the rate of biochemical recurrence

[25][13][17][24][26][27][28][29][30]. A cutoff of 3 mm of linear extent of positive margins has been used in many studies to distinguish limited from extensive margin positivity, and is the cutoff recommended by the College of American Pathologists protocol

[3]. Koskas et al. in a retroperspective study with an 8-year period of follow up demonstrated that extended or multifocal positive MOR is linked with earlier and higher rates of recurrence compared to limited positive margins

[12]. They also found that Gleason score or pT stage does not influence in a statistical significant way the length of positive margins, whereas focal marginal infiltration does not affect the rate of biochemical recurrence

[12]. Similarly, it has been shown that focal infiltration of MOR correlates with biochemical but not with clinical recurrence

[22]. Extensive invasion of surgical margins is accompanied by a 35% chance of 5-year recurrence-free survival, compared with 60% for limited MOR and 87% for prostatectomies with organ-confined disease

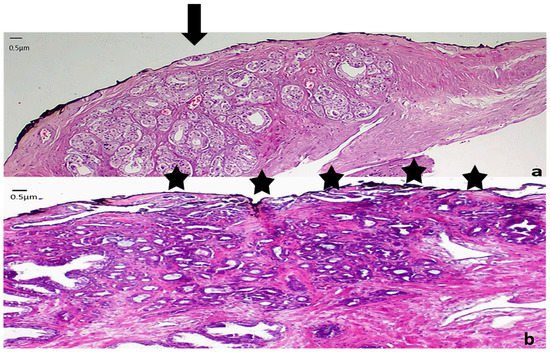

[7]. More recently, a lack of a significant difference in biochemical recurrence between patients with negative and short (<3 mm) (

Figure 3) positive MOR has been shown

[31][32]. In addition, when invasion of margins is unifocal, the biochemical-free period is not shortened

[31][12]. The limited prognostic value of short and unifocal positive MOR may be accounted by a potential false interpretation of the margin, due to artifacts during the handling of the specimens. In addition, the few neoplastic cells remaining in the margins may not be not able to multiply and metastasize

[32], and the cautery and ischemic effect of surgery may have destroyed the limited amount of neoplasm that has remained in the patient

[7]. Taking into account these findings, the extension and the topography of positive MOR should be seriously considered when planning therapeutic interventions, as it is considered an independent adverse prognostic factor

[15]. NCCN define as diffuse margins that are >10 mm or involving ≥ 3 sites

[23]. A consideration for adjuvant treatment should be given for patients with extensive positive margins

[22].

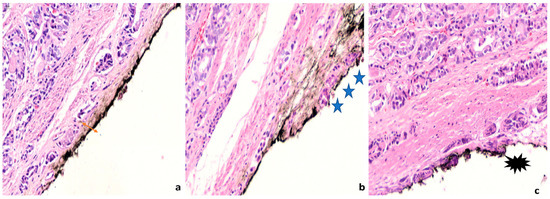

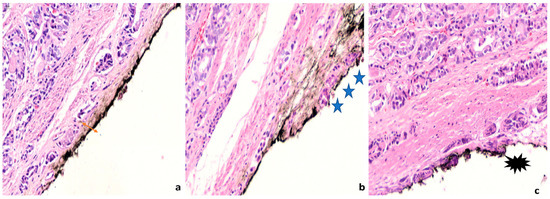

Figure 3. Representative images from low grade carcinomas with positive margins of different extent (a) Focal margin infiltration with neoplasm graded as PGG1. An arrow indicates the area of margin positivity (100× magnification) (b) Nonfocal margin infiltration with neoplasm graded as PGG1. Five asterisks point the area of margin positivity. (40× magnification).

Gleason score of the tumor at the positive margin has also been associated with the prognosis

[33][34][35][36], albeit in some studies it has been found that it is not an independent factor

[18]. A recent meta-analysis of 10 retrospective cohort studies, found that primary Gleason grade 4 or 5 at the margin was predictive of biochemical-free recurrence

[37]. Prognostic grade group (PGG) 1 at the margin has been shown to have biochemical recurrence rates

[35] and cancer-specific survival

[36] equivalent to those of negative margins. Paradoxically, when Gleason score 6 tumors are accompanied by extensive (>3 mm) positive MOR, there might be an increased risk of recurrence

[26]. That means that PGG1 tumor at the margin, especially when limited in extent, is not capable of progression, in concordance with the indolent nature of Gleason 6 tumors

[38]. In contrast, PGG2-5 tumors at the margin have a higher rate of biochemical recurrence compared to PGG1

[37], and the presence of Gleason grade 4 at the margin in patients with Gleason score 7 tumors is associated with worse cancer-specific survival compared to the presence of Gleason grade 3 at the margin, independently of the tumor’s Gleason score and the use of adjuvant therapy

[36]. These data support the report of the Gleason Score of the neoplastic glands that are present at the margin in the pathology assessment of prostatectomy specimens, also recommended by the College of American Pathologists

[3].

Probability of margin positivity differs in the different areas of the prostate, as does its prognostic significance. Apex is the most common location for positive MOR, followed by the posterolateral and the posterior surface

[7][10][39][11][12][13][26]. The frequent positivity of the margins at the apex is attributed to the lack of a clear plane of resection in this area, its close proximity to vital structures such as the dorsal venous complex and the neurovascular bundles and the agony of the surgeon to preserve the maximum length of the urethra, thus limiting the urological complications postoperatively

[39]. In addition, the apex is surrounded by a very thin and fragile capsule where the benign glands are admixed with skeletal muscles, thus, it is prone to fragmentation during its handling by the surgeon

[39]. The lack of periprostatic adipose tissue and the interminglement and graduate transition of the prostate parenchyma to the external urethral sphincter at the apex

[1] make the definition of margin positivity and whether it is related to extraprostatic extension or intraprostatic excision difficult in this area

[7].