Despite an intensive research effort in the past few decades, prostate cancer (PC) remains a top cause of cancer death in men, particularly in the developed world. The major cause of fatality is the progression of local prostate cancer to metastasis disease. Treatment of patients with metastatic prostate cancer (mPC) is generally ineffective. Based on the discovery of mPC relying on androgen for growth, many patients with mPC show an initial response to the standard of care: androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). However, lethal castration resistant prostate cancers (CRPCs) commonly develop. It is widely accepted that intervention of metastatic progression of PC is a critical point of intervention to reduce PC death. Accumulative evidence reveals a role of RKIP in suppression of PC progression towards mPC.

- prostate cancer

- metastasis

- RKIP

- signaling events

1. Introduction

2. RKIP as a Tumor Suppression of Prostate Cancer (PC)

Consistent with RIKP’s potential role in molecular events relevant to tumor suppression, RKIP downregulations, and RKIP’s associations with cancer progression, RKIP-derived tumor suppressive activities have been reported in multiple cancer types, including urogenital cancers (bladder cancer [84][38], clear cell renal cell carcinoma [85[39][40][41],86,87], and PC [88,89][42][43]), breast cancer [90][44], pancreatic cancer [91][45], hepatoma [92][46], non-small cell lung cancer [93][47], gastric cancer [94][48], and others [95][49].2.1. RKIP-Mediated Suppression of PC Tumorigenesis and Metastasis

2.1.1. Facilitation of PC Initiation and Metastasis via Downregulation of RKIP at the Protein Level

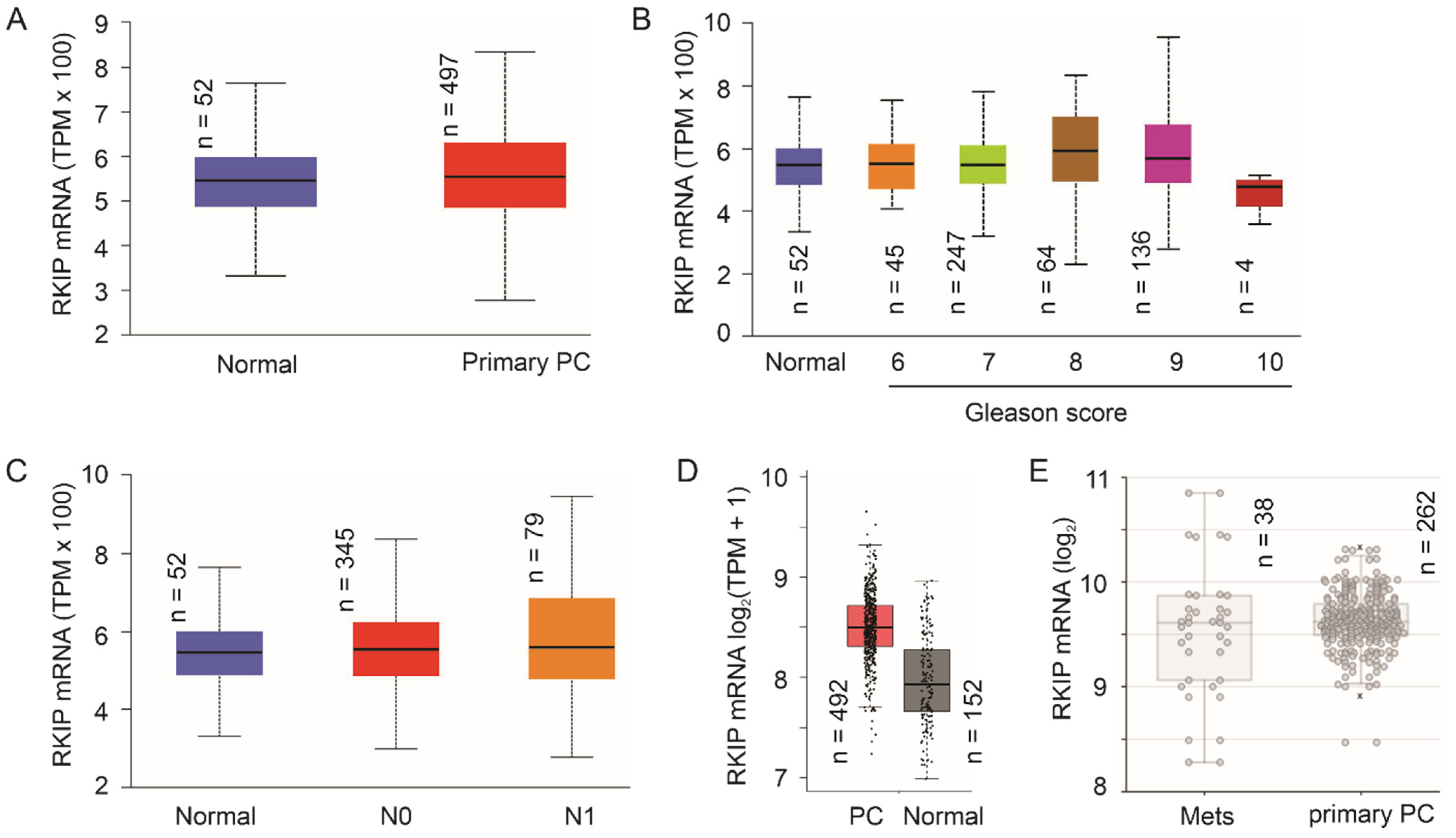

2.1.2. No Apparent Reduction of RKIP mRNA Expression Following PC Pathogenesis

2.2. Regulation of RKIP Expression in PC Cells

2.2.1. RKIP as a Target of Androgen Receptor (AR)

2.2.2. Mutual Regulation of RKIP and the EMT Machinery

2.2.3. Non-Coding RNA-Mediated Downregulation of RKIP in PC Cells

2.3. RKIP-Derived Sensitization of PC Cells to Treatment In Vitro

3. Conclusions

The research activities in the past 20 years collectively demonstrated RKIP as a tumor suppressor of PC tumorigenesis and metastasis. This knowledge is supported by (1) functional evidence derived from in vitro, in vivo (xenograft and transgenic mouse models), and clinical studies as well as (2) mechanistic pathways contributing to RKIP-derived suppression of PC. Future research should explore the functionality and underlying mechanisms for RKIP mediated suppression of PC using more refined transgenic models, including mice with prostate-specific expression of RKIP and its mutants. The latter may help to define the regulations relevant to RKIP tumor suppressive actions; this is important, as RKIP can be switched to promote tumorigenesis following its phosphorylation at S153 (Figure 2). Additionally, mechanisms leading to RKIP downregulation in PC and RKIP’s involvement in other aspects of PC progression should also be investigated (see Section 5 for details).References

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386.

- Heidenreich, A.; Bastian, P.J.; Bellmunt, J.; Bolla, M.; Joniau, S.; van der Kwast, T.; Mason, M.; Matveev, V.; Wiegel, T.; Zattoni, F.; et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 467–479.

- Egevad, L.; Delahunt, B.; Srigley, J.R.; Samaratunga, H. International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grading of prostate cancer—An ISUP consensus on contemporary grading. APMIS Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. 2016, 124, 433–435.

- Gordetsky, J.; Epstein, J. Grading of prostatic adenocarcinoma: Current state and prognostic implications. Diagn. Pathol. 2016, 11, 25.

- Epstein, J.I.; Zelefsky, M.J.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Nelson, J.B.; Egevad, L.; Magi-Galluzzi, C.; Vickers, A.J.; Parwani, A.V.; Reuter, V.E.; Fine, S.W.; et al. A Contemporary Prostate Cancer Grading System: A Validated Alternative to the Gleason Score. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 428–435.

- Mottet, N.; Bellmunt, J.; Bolla, M.; Briers, E.; Cumberbatch, M.G.; De Santis, M.; Fossati, N.; Gross, T.; Henry, A.M.; Joniau, S.; et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part 1: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 618–629.

- Bill-Axelson, A.; Holmberg, L.; Garmo, H.; Rider, J.R.; Taari, K.; Busch, C.; Nordling, S.; Haggman, M.; Andersson, S.O.; Spangberg, A.; et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 932–942.

- Hayes, J.H.; Ollendorf, D.A.; Pearson, S.D.; Barry, M.J.; Kantoff, P.W.; Lee, P.A.; McMahon, P.M. Observation versus initial treatment for men with localized, low-risk prostate cancer: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 853–860.

- Godtman, R.A.; Holmberg, E.; Khatami, A.; Stranne, J.; Hugosson, J. Outcome following active surveillance of men with screen-detected prostate cancer. Results from the Goteborg randomised population-based prostate cancer screening trial. Eur. Urol. 2013, 63, 101–107.

- Zaorsky, N.G.; Raj, G.V.; Trabulsi, E.J.; Lin, J.; Den, R.B. The dilemma of a rising prostate-specific antigen level after local therapy: What are our options? Semin. Oncol. 2013, 40, 322–336.

- Cornford, P.; Bellmunt, J.; Bolla, M.; Briers, E.; De Santis, M.; Gross, T.; Henry, A.M.; Joniau, S.; Lam, T.B.; Mason, M.D.; et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part II: Treatment of Relapsing, Metastatic, and Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 630–642.

- Pound, C.R.; Partin, A.W.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Chan, D.W.; Pearson, J.D.; Walsh, P.C. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA 1999, 281, 1591–1597.

- Boorjian, S.A.; Thompson, R.H.; Tollefson, M.K.; Rangel, L.J.; Bergstralh, E.J.; Blute, M.L.; Karnes, R.J. Long-term risk of clinical progression after biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy: The impact of time from surgery to recurrence. Eur. Urol. 2011, 59, 893–899.

- Lytton, B. Prostate cancer: A brief history and the discovery of hormonal ablation treatment. J. Urol 2001, 165, 1859–1862.

- Wong, Y.N.; Ferraldeschi, R.; Attard, G.; de Bono, J. Evolution of androgen receptor targeted therapy for advanced prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11, 365–376.

- Semenas, J.; Allegrucci, C.; Boorjian, S.A.; Mongan, N.P.; Persson, J.L. Overcoming drug resistance and treating advanced prostate cancer. Curr. Drug Targets 2012, 13, 1308–1323.

- Ojo, D.; Lin, X.; Wong, N.; Gu, Y.; Tang, D. Prostate Cancer Stem-like Cells Contribute to the Development of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2015, 7, 2290–2308.

- de Bono, J.S.; Logothetis, C.J.; Molina, A.; Fizazi, K.; North, S.; Chu, L.; Chi, K.N.; Jones, R.J.; Goodman, O.B., Jr.; Saad, F.; et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1995–2005.

- Scher, H.I.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Taplin, M.E.; Sternberg, C.N.; Miller, K.; de Wit, R.; Mulders, P.; Chi, K.N.; Shore, N.D.; et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1187–1197.

- Chaturvedi, S.; Garcia, J.A. Novel agents in the management of castration resistant prostate cancer. J. Carcinog. 2014, 13, 5.

- Drake, C.G. Prostate cancer as a model for tumour immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 580–593.

- Mei, W.; Gu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Major, P.; Tang, D. Circulating cell-free DNA is a potential prognostic biomarker of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer for taxane therapy. AME Med. J. 2018, 3, 1–5.

- Weigelt, B.; Peterse, J.L.; van ‘t Veer, L.J. Breast cancer metastasis: Markers and models. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 591–602.

- Gupta, G.P.; Massague, J. Cancer metastasis: Building a framework. Cell 2006, 127, 679–695.

- De Craene, B.; Berx, G. Regulatory networks defining EMT during cancer initiation and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 97–110.

- Tsai, J.H.; Yang, J. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in carcinoma metastasis. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 2192–2206.

- Shibue, T.; Weinberg, R.A. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: The mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 611–629.

- Mei, W.; Lin, X.; Kapoor, A.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, K.; Tang, D. The Contributions of Prostate Cancer Stem Cells in Prostate Cancer Initiation and Metastasis. Cancers 2019, 11, 434.

- Yan, C.; Theodorescu, D. RAL GTPases: Biology and Potential as Therapeutic Targets in Cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2018, 70, 1–11.

- Makwana, V.; Rudrawar, S.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S. Signalling transduction of O-GlcNAcylation and PI3K/AKT/mTOR-axis in prostate cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166129.

- Wu, X.; Scott, H.; Carlsson, S.V.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Cerundolo, L.; Lilja, H.; Prevo, R.; Rieunier, G.; Macaulay, V.; Higgins, G.S.; et al. Increased EZH2 expression in prostate cancer is associated with metastatic recurrence following external beam radiotherapy. Prostate 2019, 79, 1079–1089.

- Liu, Q.; Wang, G.; Li, Q.; Jiang, W.; Kim, J.S.; Wang, R.; Zhu, S.; Wang, X.; Yan, L.; Yi, Y.; et al. Polycomb group proteins EZH2 and EED directly regulate androgen receptor in advanced prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 415–426.

- Zhao, Y.; Ding, L.; Wang, D.; Ye, Z.; He, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhu, R.; Pan, Y.; Wu, Q.; Pang, K.; et al. EZH2 cooperates with gain-of-function p53 mutants to promote cancer growth and metastasis. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e99599.

- Ren, D.; Yang, Q.; Dai, Y.; Guo, W.; Du, H.; Song, L.; Peng, X. Oncogenic miR-210-3p promotes prostate cancer cell EMT and bone metastasis via NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 117.

- Kaltschmidt, C.; Banz-Jansen, C.; Benhidjeb, T.; Beshay, M.; Forster, C.; Greiner, J.; Hamelmann, E.; Jorch, N.; Mertzlufft, F.; Pfitzenmaier, J.; et al. A Role for NF-kappaB in Organ Specific Cancer and Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 655.

- Keller, E.T.; Fu, Z.; Brennan, M. The biology of a prostate cancer metastasis suppressor protein: Raf kinase inhibitor protein. J. Cell Biochem. 2005, 94, 273–278.

- Keller, E.T.; Fu, Z.; Yeung, K.; Brennan, M. Raf kinase inhibitor protein: A prostate cancer metastasis suppressor gene. Cancer Lett. 2004, 207, 131–137.

- Zaravinos, A.; Chatziioannou, M.; Lambrou, G.I.; Boulalas, I.; Delakas, D.; Spandidos, D.A. Implication of RAF and RKIP genes in urinary bladder cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. POR 2011, 17, 181–190.

- Moon, A.; Park, J.Y.; Sung, J.Y.; Park, Y.K.; Kim, Y.W. Reduced expression of Raf-1 kinase inhibitory protein in renal cell carcinoma: A significant prognostic marker. Pathology 2012, 44, 534–539.

- Hill, B.; De Melo, J.; Yan, J.; Kapoor, A.; He, L.; Cutz, J.C.; Feng, X.; Bakhtyar, N.; Tang, D. Common reduction of the Raf kinase inhibitory protein in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 7406–7419.

- Papale, M.; Vocino, G.; Lucarelli, G.; Rutigliano, M.; Gigante, M.; Rocchetti, M.T.; Pesce, F.; Sanguedolce, F.; Bufo, P.; Battaglia, M.; et al. Urinary RKIP/p-RKIP is a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 40412–40424.

- Fu, Z.; Smith, P.C.; Zhang, L.; Rubin, M.A.; Dunn, R.L.; Yao, Z.; Keller, E.T. Effects of raf kinase inhibitor protein expression on suppression of prostate cancer metastasis. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 878–889.

- Fu, Z.; Kitagawa, Y.; Shen, R.; Shah, R.; Mehra, R.; Rhodes, D.; Keller, P.J.; Mizokami, A.; Dunn, R.; Chinnaiyan, A.M.; et al. Metastasis suppressor gene Raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) is a novel prognostic marker in prostate cancer. Prostate 2006, 66, 248–256.

- Dangi-Garimella, S.; Yun, J.; Eves, E.M.; Newman, M.; Erkeland, S.J.; Hammond, S.M.; Minn, A.J.; Rosner, M.R. Raf kinase inhibitory protein suppresses a metastasis signalling cascade involving LIN28 and let-7. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 347–358.

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Tang, X.; Zhang, A.; Grabinski, T.; Guo, Z.; Hudson, E.; Berghuis, B.; Webb, C.; Zhao, P.; et al. Development and evaluation of monoclonal antibodies against phosphatidylethanolamine binding protein 1 in pancreatic cancer patients. J. Immunol. Methods 2010, 362, 151–160.

- Lee, H.C.; Tian, B.; Sedivy, J.M.; Wands, J.R.; Kim, M. Loss of Raf kinase inhibitor protein promotes cell proliferation and migration of human hepatoma cells. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 1208–1217.

- Wang, Q.; Wu, X.; Wu, T.; Li, G.M.; Shi, Y. Clinical significance of RKIP mRNA expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour. Biol. 2014, 35, 4377–4380.

- Zhang, X.M.; Gu, H.; Yan, L.; Zhang, G.Y. RKIP inhibits the malignant phenotypes of gastric cancer cells. Neoplasma 2013, 60, 196–202.

- Lamiman, K.; Keller, J.M.; Mizokami, A.; Zhang, J.; Keller, E.T. Survey of Raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) in multiple cancer types. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2014, 19, 455–468.

- Fu, Z.; Dozmorov, I.M.; Keller, E.T. Osteoblasts produce soluble factors that induce a gene expression pattern in non-metastatic prostate cancer cells, similar to that found in bone metastatic prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2002, 51, 10–20.

- Escara-Wilke, J.; Keller, J.M.; Ignatoski, K.M.; Dai, J.; Shelley, G.; Mizokami, A.; Zhang, J.; Yeung, M.L.; Yeung, K.C.; Keller, E.T. Raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP) deficiency decreases latency of tumorigenesis and increases metastasis in a murine genetic model of prostate cancer. Prostate 2015, 75, 292–302.

- Theroux, S.; Pereira, M.; Casten, K.S.; Burwell, R.D.; Yeung, K.C.; Sedivy, J.M.; Klysik, J. Raf kinase inhibitory protein knockout mice: Expression in the brain and olfaction deficit. Brain Res. Bull. 2007, 71, 559–567.

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Bashel, B.; Balasubramanya, S.A.H.; Creighton, C.J.; Ponce-Rodriguez, I.; Chakravarthi, B.; Varambally, S. UALCAN: A Portal for Facilitating Tumor Subgroup Gene Expression and Survival Analyses. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 649–658.

- Tang, Z.; Kang, B.; Li, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W556–W560.

- Taylor, B.S.; Schultz, N.; Hieronymus, H.; Gopalan, A.; Xiao, Y.; Carver, B.S.; Arora, V.K.; Kaushik, P.; Cerami, E.; Reva, B.; et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 11–22.

- Mitsiades, N. A road map to comprehensive androgen receptor axis targeting for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 4599–4605.

- Mateo, J.; Smith, A.; Ong, M.; de Bono, J.S. Novel drugs targeting the androgen receptor pathway in prostate cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014, 33, 567–579.

- Bello, D.; Webber, M.M.; Kleinman, H.K.; Wartinger, D.D.; Rhim, J.S. Androgen responsive adult human prostatic epithelial cell lines immortalized by human papillomavirus 18. Carcinogenesis 1997, 18, 1215–1223.

- Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Keller, J.M.; Yeung, K.; Keller, E.T.; Fu, Z. Transcriptional regulation of RKIP expression by androgen in prostate cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 30, 1340–1350.

- Yeh, S.; Tsai, M.Y.; Xu, Q.; Mu, X.M.; Lardy, H.; Huang, K.E.; Lin, H.; Yeh, S.D.; Altuwaijri, S.; Zhou, X.; et al. Generation and characterization of androgen receptor knockout (ARKO) mice: An in vivo model for the study of androgen functions in selective tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13498–13503.

- Quigley, C.A.; De Bellis, A.; Marschke, K.B.; el-Awady, M.K.; Wilson, E.M.; French, F.S. Androgen receptor defects: Historical, clinical, and molecular perspectives. Endocr. Rev. 1995, 16, 271–321.

- Heinlein, C.A.; Chang, C. Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr. Rev. 2004, 25, 276–308.

- Kim, J.; Coetzee, G.A. Prostate specific antigen gene regulation by androgen receptor. J. Cell Biochem. 2004, 93, 233–241.

- Ben Jemaa, A.; Bouraoui, Y.; Sallami, S.; Nouira, Y.; Oueslati, R. A comparison of the biological features of prostate cancer with (PSA+, PSMA+) profile according to RKIP. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 409179.

- Roehl, K.A.; Han, M.; Ramos, C.G.; Antenor, J.A.; Catalona, W.J. Cancer progression and survival rates following anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy in 3478 consecutive patients: Long-term results. J. Urol. 2004, 172, 910–914.

- Freedland, S.J.; Humphreys, E.B.; Mangold, L.A.; Eisenberger, M.; Dorey, F.J.; Walsh, P.C.; Partin, A.W. Risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA 2005, 294, 433–439.

- Verras, M.; Lee, J.; Xue, H.; Li, T.H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z. The androgen receptor negatively regulates the expression of c-Met: Implications for a novel mechanism of prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 967–975.

- Carver, B.S.; Chapinski, C.; Wongvipat, J.; Hieronymus, H.; Chen, Y.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Arora, V.K.; Le, C.; Koutcher, J.; Scher, H.; et al. Reciprocal feedback regulation of PI3K and androgen receptor signaling in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 575–586.

- Mulholland, D.J.; Tran, L.M.; Li, Y.; Cai, H.; Morim, A.; Wang, S.; Plaisier, S.; Garraway, I.P.; Huang, J.; Graeber, T.G.; et al. Cell autonomous role of PTEN in regulating castration-resistant prostate cancer growth. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 792–804.

- Marcelli, M.; Haidacher, S.J.; Plymate, S.R.; Birnbaum, R.S. Altered growth and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 production in PC3 prostate carcinoma cells stably transfected with a constitutively active androgen receptor complementary deoxyribonucleic acid. Endocrinology 1995, 136, 1040–1048.

- Xinzhou, H.; Ning, Y.; Ou, W.; Xiaodan, L.; Fumin, Y.; Huitu, L.; Wei, Z. RKIp inhibits the migration and invasion of human prostate cancer PC-3M cells through regulation of extracellular matrix. Mol. Biol. 2011, 45, 1004–1011.

- Al-Mulla, F.; Bitar, M.S.; Al-Maghrebi, M.; Behbehani, A.I.; Al-Ali, W.; Rath, O.; Doyle, B.; Tan, K.Y.; Pitt, A.; Kolch, W. Raf kinase inhibitor protein RKIP enhances signaling by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 1334–1343.

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 178–196.

- Cho, E.S.; Kang, H.E.; Kim, N.H.; Yook, J.I. Therapeutic implications of cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Arch. Pharm Res. 2019, 42, 14–24.

- Lv, W.; Huan, M.; Yang, W.; Gao, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, S.; Zhang, M.; Ma, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Snail promotes prostate cancer migration by facilitating SPOP ubiquitination and degradation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 529, 799–804.

- Beach, S.; Tang, H.; Park, S.; Dhillon, A.S.; Keller, E.T.; Kolch, W.; Yeung, K.C. Snail is a repressor of RKIP transcription in metastatic prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 2008, 27, 2243–2248.

- Baritaki, S.; Yeung, K.; Palladino, M.; Berenson, J.; Bonavida, B. Pivotal roles of snail inhibition and RKIP induction by the proteasome inhibitor NPI-0052 in tumor cell chemoimmunosensitization. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 8376–8385.

- Salmena, L.; Poliseno, L.; Tay, Y.; Kats, L.; Pandolfi, P.P. A ceRNA hypothesis: The Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell 2011, 146, 353–358.

- Lopez-Urrutia, E.; Bustamante Montes, L.P.; Ladron de Guevara Cervantes, D.; Perez-Plasencia, C.; Campos-Parra, A.D. Crosstalk Between Long Non-coding RNAs, Micro-RNAs and mRNAs: Deciphering Molecular Mechanisms of Master Regulators in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 669.

- Du, Y.; Liu, X.H.; Zhu, H.C.; Wang, L.; Ning, J.Z.; Xiao, C.C. MiR-543 Promotes Proliferation and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Prostate Cancer via Targeting RKIP. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 41, 1135–1146.

- Du, Y.; Weng, X.D.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.H.; Zhu, H.C.; Guo, J.; Ning, J.Z.; Xiao, C.C. LncRNA XIST acts as a tumor suppressor in prostate cancer through sponging miR-23a to modulate RKIP expression. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 94358–94370.

- Ahmed, M.; Lai, T.H.; Zada, S.; Hwang, J.S.; Pham, T.M.; Yun, M.; Kim, D.R. Functional Linkage of RKIP to the Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition and Autophagy during the Development of Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 273.

- Aakula, A.; Kohonen, P.; Leivonen, S.K.; Makela, R.; Hintsanen, P.; Mpindi, J.P.; Martens-Uzunova, E.; Aittokallio, T.; Jenster, G.; Perala, M.; et al. Systematic Identification of MicroRNAs That Impact on Proliferation of Prostate Cancer Cells and Display Changed Expression in Tumor Tissue. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 1120–1128.

- Wang, D.; Cai, L.; Tian, X.; Li, W. MiR-543 promotes tumorigenesis and angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer via modulating metastasis associated protein 1. Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 44.

- Wang, S.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Z.; Geng, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, N.; Cai, X. LINC-PINT alleviates lung cancer progression via sponging miR-543 and inducing PTEN. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 1999–2009.

- Su, D.W.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Dou, J.; Fang, G.E.; Luo, C.J. MiR-543 inhibits proliferation and metastasis of human colorectal cancer cells by targeting PLAS3. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 8812–8821.

- Liu, X.; Gan, L.; Zhang, J. miR-543 inhibites cervical cancer growth and metastasis by targeting TRPM7. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 302, 83–92.

- Fu, Q.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Lv, G.; Dong, S. MicroRNA-335 and -543 suppress bone metastasis in prostate cancer via targeting endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 1417–1425.

- Wang, Y.C.; He, W.Y.; Dong, C.H.; Pei, L.; Ma, Y.L. lncRNA HCG11 regulates cell progression by targeting miR-543 and regulating AKT/mTOR pathway in prostate cancer. Cell Biol. Int. 2019, 43, 1453–1462.

- Wang, X.; Yang, J.Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, D.J.; Zhao, L.; Luo, L.H.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jin, M. MiR-543/Numb promotes proliferation, metastasis, and stem-like cell traits of prostate cancer cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 617–631.

- Baritaki, S.; Huerta-Yepez, S.; Sahakyan, A.; Karagiannides, I.; Bakirtzi, K.; Jazirehi, A.; Bonavida, B. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of EMT in cancer: Inhibition of the metastasis-inducer Snail and induction of the metastasis-suppressor RKIP. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 4931–4940.

- Della Pietra, E.; Simonella, F.; Bonavida, B.; Xodo, L.E.; Rapozzi, V. Repeated sub-optimal photodynamic treatments with pheophorbide a induce an epithelial mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer cells via nitric oxide. Nitric Oxide 2015, 45, 43–53.

- Rapozzi, V.; Varchi, G.; Della Pietra, E.; Ferroni, C.; Xodo, L.E. A photodynamic bifunctional conjugate for prostate cancer: An in vitro mechanistic study. Investig. New Drugs 2017, 35, 115–123.

- Kashyap, V.; Bonavida, B. Role of YY1 in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer and correlation with bioinformatic data sets of gene expression. Genes Cancer 2014, 5, 71–83.

- D’Este, F.; Della Pietra, E.; Badillo Pazmay, G.V.; Xodo, L.E.; Rapozzi, V. Role of nitric oxide in the response to photooxidative stress in prostate cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 182, 114205.

- Chatterjee, D.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Beach, S.; Mott, S.; Roy, R.; Braastad, C.; Sun, Y.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Aggarwal, B.B.; et al. RKIP sensitizes prostate and breast cancer cells to drug-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 17515–17523.

- Woods Ignatoski, K.M.; Grewal, N.K.; Markwart, S.M.; Vellaichamy, A.; Chinnaiyan, A.M.; Yeung, K.; Ray, M.E.; Keller, E.T. Loss of Raf kinase inhibitory protein induces radioresistance in prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008, 72, 153–160.

- Tannock, I.F.; de Wit, R.; Berry, W.R.; Horti, J.; Pluzanska, A.; Chi, K.N.; Oudard, S.; Theodore, C.; James, N.D.; Turesson, I.; et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1502–1512.

- Berthold, D.R.; Pond, G.R.; Soban, F.; de Wit, R.; Eisenberger, M.; Tannock, I.F. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer: Updated survival in the TAX 327 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 242–245.

- Zhu, C.X.; Li, W.Z.; Guo, Y.L.; Chen, L.; Li, G.H.; Yu, J.J.; Shu, B.; Peng, S. Tumor suppressor RKIP inhibits prostate cancer cell metastasis and sensitizes prostate cancer cells to docetaxel treatment. Neoplasma 2018, 65, 228–233.