Fusarium wilt disease is one of the major diseases causing a decline in watermelon yield and quality. Researches have informed that phytohormones play essential roles in regulating plants growth, development, and stress defendants. However, the molecular mechanism of salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and abscisic acid (ABA) in resistance to watermelon Fusarium wilt remains unknown. In this experiment, we established the SA, JA, and ABA determination system in watermelon roots, and analyzed their roles in against watermelon Fusarium wilt compared to the resistant and susceptible varieties using transcriptome sequencing and RT-qPCR. Our results revealed that the up-regulated expression of Cla97C09G174770, Cla97C05G089520, Cla97C05G081210, Cla97C04G071000, and Cla97C10G198890 genes in resistant variety were key factors against (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Niveum) FON infection at 7 dpi. Additionally, there might be crosstalk between SA, JA, and ABA, caused by those differentially expressed (non-pathogen-related) NPRs, (Jasmonate-resistant) JAR, and (Pyrabactin resistance 1-like) PYLs genes, to trigger the plant immune system against FON infection. Overall, our results provide a theoretical basis for watermelon resistance breeding, in which phytohormones participate.

1. Introduction

Watermelon (

Citrullus lanatus)

Fusarium wilt disease pose a serious threat to watermelon quality and yield

[1][2][3][1,2,3]. Different techniques, including chemical control

[4], biological control

[5][6][5,6], grafting

[7], and the use of disease-resistant cultivars

[8], are utilized to overcome this disease. Many researchers have focused on recognition competition between the host plants, pathogens, pathogenic factors, and host plant defense factors

[9][10][11][9,10,11]. Phytohormones were reported as signaling molecules acting in plant communication, which play important roles in plant growth and stress responses

[11][12][13][11,12,13]. For example, salicylic acid (SA) has an essential role in systemic acquired resistance (SAR)

[14] and is also involved in shaping the plant microbiomes to increase the plant immune capacity

[15]. Jasmonic acid (JA) is recognized as another major defense hormone, which identified crosstalk between SA pathways

[16][17][16,17]. Resent discoveries reported the important role of abscisic acid (ABA) to abiotic stress, and it has emerged as a modulator of the plant immune signaling network

[18][19][18,19]. Similarly, most studies have demonstrated that SA synthesis is induced under stress conditions in watermelon. For instance, Zhu comparatively analyzed two contrasting watermelon genotypes during fruit development and ripening based on transcriptome, and suggested that ABA and ethylene might equally contribute to regulating watermelon fruit quality

[20]. Xu’s research has noticed that JA biosynthesis genes were induced and activated at the early stage of (

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Niveum) FON infection in watermelon cultivated accompanying by wheat

[21]. Cheng found out that low temperature induced SA production, and it might cooperate with redox signaling to regulate watermelon resistance

[22]. Moreover, Guang recently identified that the exogenous JA, SA, and ET treatment significantly up-regulated the CIOPR gene under root knot nematode infection

[23]. Therefore, we hypothesized that phytohormones may play a crosstalk role in triggering the watermelon plant immune system.

With the rapid development of molecular biology, some new biotechnology methods have been widely used in watermelon plant breeding, as well as disease resistance

[23][24][25][23,24,25]. For instance, Guo has identified the genome sketch of watermelon material 97103 and analyzed its genomics, which has paved the way for botanists to study watermelon at molecular level

[24]. Li has identified many disease resistance-related candidate genes during the infection process of watermelon fruit against Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus (CGMMV) by RNA Seq, which lay a foundation for further gene functional study

[25]. However, the molecular mechanism of phytohormones network relationships in watermelon plants was less known. Therefore, in this experiment, our aim is to explore the essential role of SA, JA, and ABA in watermelon resistance to

Fusarium wilt disease by comparing differences in their concentration and signal-related gene expression in resistant and susceptible varieties. These studies will provide a comprehensive resource for identify the genes associated with the phytohormones of watermelon resistance breeding.

2. Comparison Analysis of Phenotype and Fusarium Wilt Disease Occurrence in Resistant and Susceptible Watermelon after FON Inoculation

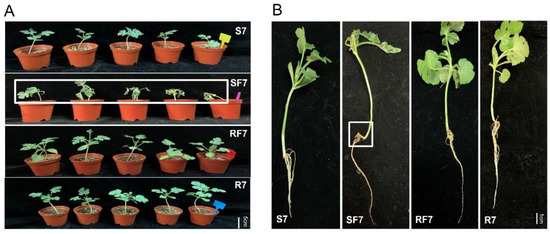

In order to clarify the effect of different watermelon varieties on

Fusarium disease resistance, the phenotypes of watermelon seedlings and the disease incidences after pathogen infection were explored. The trial crops were watermelon resistance cultivated variety PI296341 and susceptible cultivated variety, zaojia 8424. The watermelon seedling nutrition bowl was cultivated and grown in a biochemical incubator at Tm 25 °C, light 16 h/Tm 18 °C, and dark 8 h. When the watermelon seedling growth stage was at two leaves apart, aliquots of 10

6 conidia/mL FON were added into the root zone of each watermelon plant. Samples referred to as S7, Susceptible cultivar + mock-inoculation control (H

2O

2), 7 dpi (7 days post inoculation); R7, Resistant cultivar + mock-inoculation control (H

2O

2), 7 dpi (7 days post inoculation); SF7, Susceptible cultivar + FON, 7 dpi (7 days post inoculation); and RF7, Resistant cultivar + FON, 7 dpi (7 days post inoculation). The results showed that the resistant watermelon seedlings grew bigger with more leaves without any disease symptoms, while the susceptible variety plants had obvious disease symptoms such as yellowing and wilting at 7 days post inoculation (

Figure 1A). Comparing analysis of the root’s phenotypic changes after FON infection shows more fibrous roots in the resistant group than that of susceptible one (

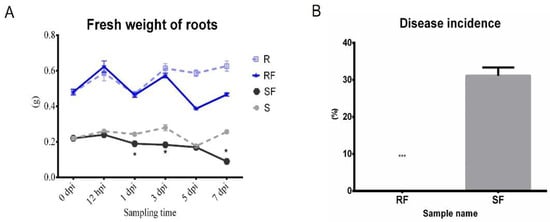

Figure 1B). The fresh weight of roots in the resistant cultivar was nearly three times heavier than that of the susceptible cultivar (

Figure 2A). Furthermore, the disease incidence of watermelon

Fusarium wilt in SF7 was 33.3%, while it was 0% in RF7 (

Figure 2B). The question is, how the resistant variety was able to control the disease.

Figure 1. Comparison analysis of watermelon performance after FON infection at 7 dpi: (A) Comparison of watermelon seeding phenotype in different samples; (B) Comparison analysis of root phenotype in different samples.

Figure 2. Comparison analysis fresh weight of roots and Fusarium wilt disease occurrence on different watermelon varieties after FON inoculation: (A) Comparison analysis of fresh weight of roots in different samples; (B) Comparison analysis of disease incidence in different samples. S, Susceptible cultivar + mock-inoculation control (H2O2); R, Resistant cultivar + mock-inoculation control (H2O2); SF, Susceptible cultivar + FON; RF, Resistant cultivar + FON. Moreover, 0 dpi (before treatment); 12 hpi (12 h post inoculation); 1 dpi (1 day post inoculation); 3 dpi (3 days post inoculation); 5 dpi (5 days post inoculation); 7 dpi (7 days post inoculation). Data were expressed as mean ± SE (n = 3). Multiple t tests of Two-way ANOVA (*, p ≤ 0.05; ***, p ≤ 0.0001).

3. Dynamic Changes in MDA Content and PAL, POD Enzyme Activities after FON Inoculation

We compared the dynamic changes in malondialdehyde (MDA) content, phylalnine ammonialyase (PAL) enzyme activity, and peroxidase (POD) enzyme activity of resistant and susceptible watermelon roots at different stages after FON infection. The results showed that there was a continuous increasing of MDA content in susceptible watermelon roots, which represented the changes in plant health condition at different stages after FON infection (

Figure 3A). After FON treatment, the POD enzyme activity in RF group was increased significantly from 12 hpi to 1 dpi, and then decreased continuously. Notably, the POD enzyme activity in SF was nearly two times higher than that in RF at 3 dpi (

Figure 3B). Our results showed that the PAL enzyme activity in RF was nearly twice as high as SF at 3 dpi, but then decreased rapidly, up to only half that compared with the SF group at 7 dpi (

Figure 3C). Our results indicate that the POD and PAL may have important roles as resistant varieties against FON infection at an early stage.

Figure 3. Comparison analysis of physiological indexes changes: (A) Dynamic changes in MDA content at different sampling time in different samples; (B) Dynamic changes in POD enzyme activities at different sampling time in different samples; (C) Dynamic changes in PAL enzyme activities at different sampling time in different samples. S, Susceptible cultivar + mock-inoculation control (H2O2); R, Resistant cultivar + mock-inoculation control (H2O2); SF, Susceptible cultivar + FON; RF, Resistant cultivar + FON. Moreover, 0 dpi (before treatment); 12 hpi (12 h post inoculation); 1 dpi (1 day post inoculation); 3 dpi (3 days post inoculation); 5 dpi (5 days post inoculation); 7 dpi (7 days post inoculation). Data were expressed as mean ± SE (n = 3). Multiple t tests of Two-way ANOVA (*, p ≤ 0.001; **, p ≤ 0.0001).

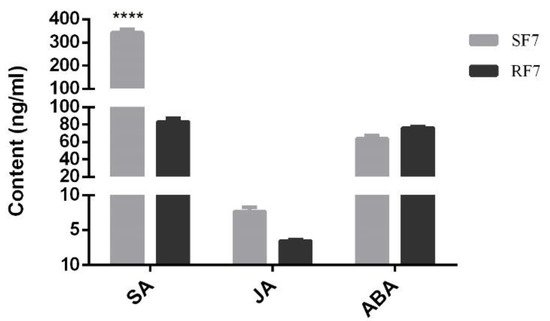

4. Comparison Analysis of SA, JA, and ABA Contents at 7 dpi

In order to explore the physiological mechanism of phytohormones in against watermelon

Fusarium wilt while the symptoms appeared (e.g., rotted, discolored), we established a determination system for the SA, JA, and ABA content in watermelon roots, as shown in

Figure S1 (supplementary could be found in https://www.

mdpi.com/2223-7747/11/2/156#supplementary). Here, we comparison analyzed the SA, JA, and ABA content in resistant and susceptible watermelon roots at 7 dpi. The results showed that the SA content in the susceptible group was significantly higher than that in the resistant group, but the content of JA and ABA had no significant difference (

Figure 4).

Figure 4. Comparison analysis of SA, JA, and ABA contents in different samples. SF7, Susceptible cultivar + FON, 7 days post inoculation (7 dpi); RF7, Resistant cultivar + FON, 7 days post inoculation (7 dpi). Data were expressed as mean ± SE (n = 3). Multiple t-test of Two-way ANOVA (****, p ≤ 0.0001).

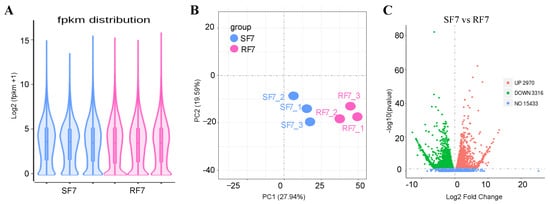

5. Comparison Analysis of Transcriptome Differences at 7 dpi

To examine the molecular mechanism of

Fusarium wilt resistance, we used transcriptome sequences to analyze the difference expressed genes between resistant and susceptible watermelon cultivars at 7 dpi as well.

The violin diagram showed that the covered distribution of gene expression levels was uniform in different samples after calculating the expression values (FPKM) of all genes (

Figure 5A). In order to further compare the different gene expressions in resistant and susceptible varieties treated by pathogens, we conducted PCA analysis on the distribution of different genes, which showed differences between these two varieties, as seen in

Figure 5B. The volcanic map indicates that there were 21,719 genes detected, with 6286 significantly differentially expressed genes compared, in which 2970 were up-expressed, and 3316 genes were down-expressed, between these two varieties (

Figure 5C).

Figure 5. RNA-Seq comparison analysis of watermelon gene expression in resistance and sensitivity varieties: (A) The violin diagram of FPKM distribution; (B) PCA analysis of different samples; (C) Volcano map of DEGs between resistant and susceptible cultivars. Note: SF7, Susceptible cultivar + FON, 7 days post inoculation (7 dpi); RF7, Resistant cultivar + FON, 7 days post inoculation (7 dpi). Three independent replicates.

6. Functional Annotation of Genes Expressed

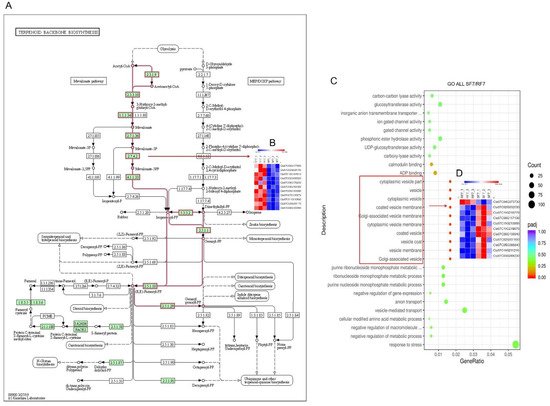

The scatter plot was used for comparison analysis of the genes’ functional enrichment in differential varieties. The KEGG enrichment significant analysis results indicate that most of the differently expressed genes were highly enriched in carbon metabolism, glutathione metabolism, biosynthesis of amino acids, glycolysis, pyruvate metabolism, and terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathways (

Figure S2A). The up-regulated differently expressed genes enriched in arachidonic acid metabolism, spliceosome, and terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathways (

Figure S2B). Furthermore, we identified that there were 10 DEGs related in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathways (

Figure 6A,B). On the other hand, the GO enrichment significant analysis results indicate that most differential genes belong to functions such as response to stress and vesicle-mediated transport. The functions of significantly differently expressed genes were mainly in the Cytoplasmic vesicle part, vesicle, cytoplasmic vesicle, coated vesicle membrane, Golgi-associated vesicle membrane, cytoplasmic vesicle membrane, coated vesicle, vesicle coat, vesicle membrane, and Golgi-associated vesicle (

Figure S2C). The heatmap showed that there were 10 down-regulated genes

(

Cla97C02G032030/Cla97C11G210770/Cla97C06G117130/Cla97C11G213000/Cla97C11G219070/Cla97C06G109940/Cla97C02G031650/Cla97C05G088840/Cla97C11G211210/Cla97C03G068230) and one up-regulated gene (

Cla97C04G073730) (

Figure 6C). In addition, the up-regulated genes were mainly enriched in response to stress, nucleus, nucleoplasm part, nucleoplasm, nuclear lumen, mediator compels, intracellular organelle lumen, organelle lumen, and membrane-enclosed lumen (

Figure 6D). In conclusion, the results laid a foundation for further study of the differential metabolic pathways in the process of watermelon resistance to

Fusarium wilt.

Figure 6. Function enrichment analysis of differential watermelon varieties: (A) Different expressed genes in Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathways; (B) Heatmap of 10 DEGs in Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis pathways; (C) All genes GO enrichment significant analysis; (D) Heatmap of 11 DEGs in GO enrichment analysis. Note: SF7, Susceptible cultivar +FON, 7 days post inoculation (7 dpi); RF7, Resistant cultivar+FON, 7 days post inoculation (7 dpi). Three independent replicates. Blue bands indicate low gene expression and red bands high gene expression.

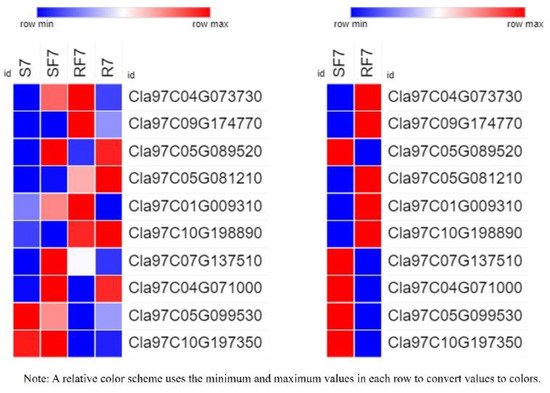

7. Analysis of Hormone-Related DEGs

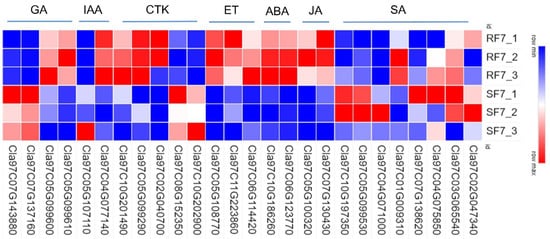

To examine the molecular mechanisms of genes involved in phytohormones signal transduction pathways, we used a heatmap to analyze the differences in resistant and susceptible watermelon varieties (

Figure 7).

Figure 7. Comparison analysis of relative expressions of candidate genes related to phytohormone pathways in resistant and susceptible samples: GA: gibberellins; IAA: auxin; CTK: cytokinin; ET: ethylene; ABA: abscisic acid; JA: jasmonic acid; SA: salicylic acid. Note: SF7, Susceptible cultivar +FON, 7 dpi; RF7, Resistant cultivar + FON, 7 dpi. Three independent replicates.

Most genes involved in the SA pathway were highly expressed in SF7 compared with RF7, where only

Cla97C01G009310 Cla97C01G009310 significantly up-regulated expression in RF7. There were 24 DEGs in the JA pathway,

Cla97C07G130430 Cla97C07G130430,

Cla97C10G192210 Cla97C10G192210,

Cla97C09G174730 Cla97C09G174730,

Cla97C10G186220 Cla97C10G186220,

Cla97C05G100240 Cla97C05G100240,

Cla97C04G078620 Cla97C04G078620,

Cla97C05G105650 Cla97C05G105650, and

Cl Cla97C05G100320, a

97C05G100320, all of which significantly up-regulated expression in RF7 compared with SF7. Among the 37 significantly DEGs involved in ABA pathway, there were 14 DEGs significantly up-regulated in the expression of RF7 compared with SF7, namely,

Cla97C06G123770 Cla97C06G123770,

Cla97C09G174770 Cla97C09G174770,

Cla97C10G186260 Cla97C10G186260,

Cla97C01G023840 Cla97C01G023840,

Cla97C11G221400 Cla97C11G221400,

Cla97C08G158420 Cla97C08G158420,

Cla97C01G010380 Cla97C01G010380,

Cla97C10G188860 Cla97C10G188860,

Cla97C09G172410 Cla97C09G172410,

Cla97C03G063210 Cla97C03G063210,

Cla97C01G020790 Cla97C01G020790,

Cla97C05G106700 Cla97C05G106700,

Cla97C07G134120 Cla97C07G134120, and

Cla97C01G006610 Cla97C01G006610. There were 48 significantly DEGs involved in the ET pathway,

Cl Cla97C06G114420 a

97C06G114420 and

Cla97C11G223860 Cla97C11G223860 highly up-regulated expression in RF7 compared with SF7; only

Cla97C05G108770 Cla97C05G108770 was expressed in RF7. There were 13 significant DEGs involved in the CTK pathway,

Cl Cla97C11G207380 a

97C11G207380 and

Cla97C05G099290 Cla97C05G099290 highly up-regulated expression in RF7 compared with SF7; only

Cla97C02G040700 Cla97C02G040700 was expressed in RF7. Among the 15 significantly DEGs involved in IAA pathway,

Cl Cla97C08G155010 a

97C08G155010 and

Cla97C11G217540 Cla97C11G217540 highly up-regulated expression in SF7 compared with RF7; only

Cla97C05G107110 Cla97C05G107110 was expressed in SF7.

Cla97C05G099610 Cla97C05G099610,

Cla97C08G145860 Cla97C08G145860, and

Cla97C05G099600 Cla97C05G099600 significantly up-regulated expression in RF7 compared with SF7 in the GA pathway (

Table S2).

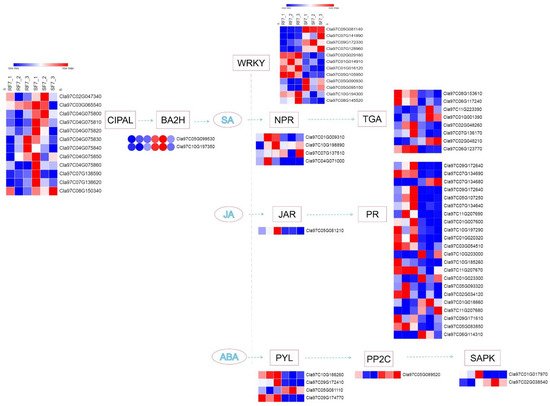

8. Bioinformatics Analysis of Candidate Genes

In our study, a number of DEGs involved in SA, JA, and ABA pathways were identified at the stage where watermelon

Fusarium wilt symptoms appeared (e.g., rotted, discolored), which was 7 days after FON inoculation. A schematic overview of DEGs related to different key components of SA, JA, and ABA signaling pathways are shown in

Figure 8.

Figure 8. The schematic of SA, JA, and ABA signaling-related genes network in watermelon roots at 7 days after FON infection: Note: SF7, Susceptible cultivar + FON, 7 days post inoculation (7 dpi); RF7, Resistant cultivar + FON, 7 days post inoculation (7 dpi). Three independent replicates. Blue bands indicate low gene expression and red bands high gene expression.

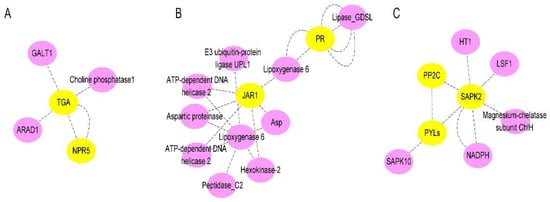

Notably, the expression of the CIPAL and BAH family genes were key to SA accumulation in watermelon plants. The interaction network of SA- (

Figure 9A), JA- (

Figure 9B), and ABA- (

Figure 9C) related genes were analyzed. We observed that there were four NPRs, one JAR, and four PYLs genes significantly expressed compared between resistant and susceptible watermelon materials. The NPR5 may activate plant immune system through TGAs, while JAR1 has interaction with pathogen-related proteins (PRs) through Lipoxygenase. The three-dimensional structures of ABA receptor PYL, specific protein phosphatases type-2C (PP2Cs), and SAPK paves the way for ABA agonists to modulate the plant stress response.

Figure 9. The schematic of SA, JA, and ABA signaling-related proteins network in watermelon: (A) Interaction network of SA signaling-related proteins in watermelon roots at 7 days after FON infection; (B) Interaction network of JA signaling-related proteins watermelon roots at 7 days after FON infection; (C) Interaction network of ABA signaling-related proteins watermelon roots at 7 days after FON infection. Each node in the diagram represents a protein, and each connecting line represents the interaction between connected proteins.

9. Expression Verification of 10 DEGs

To further test the hypotheses about the different expressed genes in differed watermelon cultivar roots, we examined evidence from the RT-qPCR results (

Table S3 and

Figure 10).

Figure 10. Relative expressions of 10 candidate genes in different samples by RT-qPCR. Note: S7, Susceptible cultivar + mock-inoculation control (H2O2), 7 dpi (7 days post inoculation); R7, Resistant cultivar + mock-inoculation control (H2O2), 7 dpi (7 days post inoculation); SF7, Susceptible cultivar + FON, 7 dpi (7 days post inoculation); RF7, Resistant cultivar + FON, 7 dpi (7 days post inoculation). Three biological replicates per samples were analyzed.

The results indicated that the gene of

Cla97C04G073730 (clathrin light chain, cellular component) was significantly activated in two varieties after FON infection at 7dpi, and results confirmed the expression of PYL (

Cla97C09G174770), PP2C (

Cla97C05G089520), JAR1 (

Cla97C05G081210), NPR (

Cla97C04G071000,

Cla97C10G198890), and BAH (

Cla97C04G071000,

Cla97C10G198890) genes had significant differences. The significant expression of NPR genes (

Cla97C04G071000,

Cla97C10G198890) suggests that they may have different functions in different watermelon cultivars to regulate plant defense systems.

10. Prediction Analysis of Phytohormones cis-Acting Regulatory Elements of 9 DEGs

The diverse expressions of JAR, NPRs, and PYLs family genes in watermelon suggest that they may play a synergistic role in regulating watermelon resistance to

Fusarium wilt. Furthermore, we analyzed nine DEGs related to JAR, NPRs, and PYLs genes to identify their phytohormones cis-elements (

Table S4). Our results indicated that the NPR genes (

Cla97C01G009310,

Cla97C07G137510, and

Cla97C04G071000) had SA, MeJA, IAA, or GA response elements but

Cla97C10G198890 only had ABA response elements. The PYL genes (

Cla97C05G081110,

Cla97C09G172410, and

Cla97C09G174770) had ABA, SA, MeJA, IAA, or GA response elements, but

Cla97C10G186260 only had MeJA response elements. Moreover, the JAR1 (

Cla97C05G081210) had ABA, SA, MeJA, IAA, and GA response elements.