Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Yvaine Wei and Version 1 by Constantinos Stathopoulos.

Date (Phoenix dactylifera L. Arecaceae) fruits and their by-products are rich in nutrients. The health benefits of dates and their incorporation into value-added products have been widely studied. The date-processing industry faces a significant sustainability challenge as more than 10% (w/w) of the production is discarded as waste or by-products. Currently, food scientists are focusing on bakery product fortification with functional food ingredients due to the high demand for nutritious food with more convenience. Utilizing date components in value-added bakery products is a trending research area with increasing attention.

- bakery products

- date fruit

- date by-products

- Sustainability

- By-product utilisation

1. Baked Goods

Improved consumer knowledge about the nutritional value of food with regard to a healthier lifestyle lowering the risk of chronic diseases has led to consumer demand toward a healthy day-to-day diet [1,2,3][1][2][3]. A current global health trend is to prevent and manage the prevalence of diseases, especially chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease, to decrease mortality levels due to these ailments through the diet. As a result, there is a growing trend to formulate functional foods making them widely available in the market. These functional foods include bakery products, dairy products, breakfast cereals, confectionery items and beverages, among others [4]. Among these, the main focus is on bakery products that are consumed as a main food on a daily basis all over the world [5,6][5][6].

There is a variety of functional ingredients used in food formulations including vitamins, minerals, dietary fiber, prebiotics, probiotics and bioactive compounds to enhance the quality and functionality of food [7,8,9,10,11,12][7][8][9][10][11][12]. Along with improving the nutritional value of food in order to improve personal health and reduce the prevalence of disease amongst the consumers, another important aspect is to maintain the required organoleptic properties of food products to secure market demand. Additionally, the consumers also look for convenience through, for instance, convenient packaging, shelf-life stability and the freshness of food products. Bakery products are the most widely consumed processed foods in almost all countries [13]. Food fortification plays a significant role in enhancing health-promoting functional components in baked products to improve value in order to meet consumer demand [14]. In this respect, bakery products have become one of the ideal food products to fulfill almost all the requirements of the consumers through fortification.

2. Baked Goods and Health

2.1. Baked Goods and Health Perspectives

Since ancient times, bakery products including bread are part of the human diet and have become one of the most consumed and most popular foods all over the world [13,15][13][15]. Bakery products include bread, biscuits, cookies, cakes, muffins, waffles, buns, crumpets, etc. Among other bakery items, biscuits and cookies possess various attractive characteristics such as relatively long shelf life, high convenience and organoleptic quality [16]. The main ingredient in bakery products is wheat flour which provides the structure and the bulk to the product [17] followed by water, yeast, salt and other ingredients.

Regular consumption of dietary fiber, as well as components such as resistant starch (RS), would help to lower the digestion of glucose and its absorption into the bloodstream. Dietary fiber, which affects various kinds of physiological parameters, is mainly responsible for gut health [35][18]. As refined wheat flour is used as a basic ingredient in bakery products, they are known to be deficient in dietary fiber [6]. Therefore, regular bread or other bakery products are not ideal for people who are suffering from diabetes or obesity as they increase the glucose levels in the blood due to digestible carbohydrates. Incorporation of functional ingredients such as dietary fiber or RS is an excellent way to overcome this issue. Natural ingredients are often added to increase the fiber content of bakery products [6,9][6][9]. Nowadays most of the research is focused on the fortification of bakery products with health-promoting ingredients. This leads not only to lowering the glycemic index of food products but can also help to minimize the risk of chronic diseases such as cancer. Specifically, antioxidants play an important role in preventing auto-oxidation in baked goods [36][19], and they help to minimize the risk of various diseases including cancer, gastrointestinal disorders and coronary heart diseases [37,38,39,40,41][20][21][22][23][24].

2.2. Attempts to Improve Quality by Addition of Plant-Based Components

A variety of bakery products are prepared incorporating natural ingredients as well as their by-products. Several developing countries where wheat is not grown much due to climatic reasons, such as Nigeria, have tried to replace wheat flour with unconventional or locally available flours in order to lower the cost of imported wheat [42][25]. For example, flour from fruits such as banana, mango and dates can be incorporated into bakery items [43,44,45,46][26][27][28][29]. When it comes to by-products, fruit peels, seeds, bagasse and sometimes over-ripe fruits can be used for fortification [47,48,49][30][31][32]. Fruits and vegetables that do not have the required size or shape can also be used as they are considered as waste in several instances since they are rejected by the consumers [50,51][33][34]. Apart from the above, functional ingredient concentrates extracted from fruits, vegetables and their by-products have also been incorporated in different food products [52,53,54,55,56][35][36][37][38][39]. Interestingly, there is a possibility to produce bakery products with high nutritional value by incorporating biologically active marine compounds such as macroalgae, microalgae, seaweeds and bioactive peptides [10].3. Date Components Used in Baked Goods

3.1. Date Fruit Components

Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L. Arecaceae) is an ancient plant cultivated mainly in desert regions including the Middle East and North Africa [116,117][40][41]. Nowadays, around 2000 cultivars are grown all over the world [118][42]. However, not every cultivar has high market demand. There are a few cultivars including Deglet Nour, Medjool and Khalas that have high economical value based on the market demand [119][43]. The main producers of date palm in the world are the UAE, Oman, Iraq, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Tunisia, Algeria, Libya and Pakistan [120][44]. The fruit from the date palm consists of date pulp (which we often call date fruit) and date seed. Date fruit, which is consumed fresh, has a dense and tacky texture facilitating mixing and binding with other ingredients such as cereals [121][45]. Therefore it has been used as a functional food ingredient in a number of food items such as bread, cookies, cakes, jam, jelly, juice, candy bars, syrups, cereals, vinegar and ice cream [122][46].

There are several stages that date fruits pass through until full ripeness including Hababouk, Kimri, Khalal or Bisser, Rutab and Tamer. In the fully ripe stage of Tamer, date fruit has a high sugar content and low moisture content, and it is brown to black in color [123][47]. The moisture content decreases throughout the ripeness stages, and hence the total solid content increases when it comes to the fully ripe stage [121][45]. Moreover, the moisture content of dates can be varied between 7% (dried) to 79% (fresh), depending on the variety [124][48].

Date fruit is a good source of carbohydrates, dietary fiber, antioxidants, minerals and vitamin B complexes [45][28]. However, the chemical composition of dates can be varied depending on different cultivars, agronomic practices, soil conditions and ripening stages [125,126][49][50].

3.2. Date By-Product Components

3.2.1. Date Seed Components

Date seeds are a secondary product derived after utilizing date pulp, and they represent around 10–15% of the date fruit’s weight, which generates a huge quantity of waste as seeds in food-processing units [128,182,183][51][52][53]. For centuries in the Arab world, date seeds have been used to make caffeine-free drinks similar to coffee [167,184][54][55]. They have also been used as animal feed [8,184,185][8][55][56] which demonstrated enhanced growth as well as estrogen and testosterone levels [186,187][57][58].

Date seeds are brown in color and odorless, with a slightly bitter taste [184][55]. Several studies have been carried out to study the nutritional value of date seeds from different geographical origins [125,184,188][49][55][59]. They contain considerable amounts of protein (5–6%) [138,189,190][60][61][62] including albumin, globulin, prolamin and glutelin as soluble proteins [190][62]. The fat content is around 8–10%, and when compared to date fruit, fat and protein content is higher in seeds [138,191,192,193][60][63][64][65]. Moreover, high amounts of carbohydrates (80–90%) were also reported in some varieties including Allig and Deglet Nour [125,189][49][61], mainly in the form of insoluble fibers [194][66].

3.2.2. Other By-Product Components

Wastes generated in date-processing units can be categorized into three main categories. Firstly, fruits that are low-grade, spoiled, etc., are thrown away during sorting. The second kind of waste is the date seeds already discussed, while the third type of waste generated during processing is date press cake (DPC) [210][67]. Other than date seeds, DPC leads to a greater loss of raw materials, as well as to the creation of environmental issues [124][48]. In date syrup or juice industries, DPC results as the primary by-product after extraction that is a fiber- and moisture-rich material [211,212][68][69]. DPC is rich in many minerals, including K, Ca, Mg, Mn and Fe [213,214][70][71]. DPC also contains a considerable amount of dietary fiber, phenolic compounds and antioxidants which could be used as a natural antioxidant source [125][49]. In addition, DPC also contains fatty acids including oleic, myristic, lauric, capric and behenic [214][71].4. Addition of Date Components into Bakery Items

4.1. Attempts to Formulate Baked Products Fortified with Date Components

Rather than attempting to formulate completely new food items, it is easier and more effective to add value to existing food products by incorporating beneficial ingredients. When it comes to baked products, most of the baking processes such as formulation, baking conditions, mixing, fermentation, etc., are optimized for almost all bakery items; however, food scientists are now focusing on trying to improve the functional and nutritional qualities of the products by fortification with beneficial ingredients. As dates are rich in a number of nutritional components, there is an evolving trend to use dates and date by-products in bakery products.

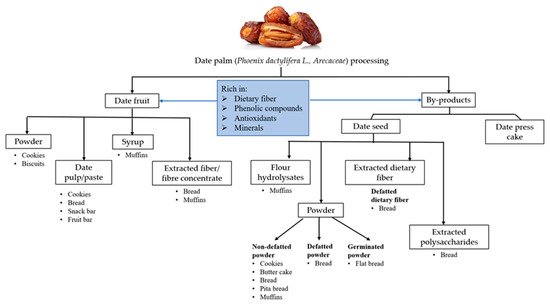

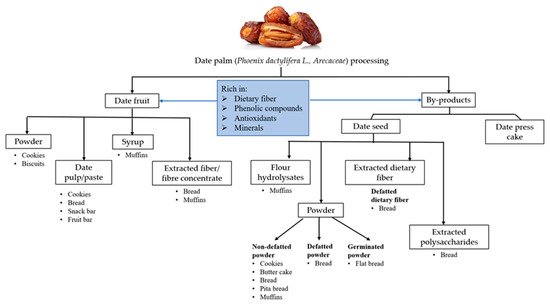

Recently there were several studies conducted formulating bakery products by incorporating dates and their by-products [8,45,46,52,54,64,145,194,198,223,224,225,226,227,228][8][28][29][35][37][72][73][66][74][75][76][77][78][79][80]. The fortification of bakery products has been done either by adding date components such as powder and paste or by adding extracted compounds, for instance, extracted dietary fiber, water-soluble polysaccharides and hemicellulose [52,54,198][35][37][74]. Bakery products that are fortified by defatted date components, specifically the seeds, have also been studied [194,228][66][80]. Some of the bakery products that have been formulated incorporating date components are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Date components incorporated into bakery products.

4.2. Effect of Addition on Product Quality and Nutritional Value

When formulating new bakery products, it is important to study the physical and chemical properties in aiding the development process. In bakery items, the most important factors are the physical and textural qualities as they consist of a particular set of characteristics that consumers demand. Apart from those, one of the biggest challenges is to secure consumer acceptance for a new fortified product. The physiochemical changes may affect consumer acceptance especially with the improved nutritional quality of a new product [235,236][81][82]. As these physiochemical changes would affect the sensory properties, it is important to assess those characteristics during processing. Most importantly, color attribute plays a special role that can change the consumers’ impression of a new food product even before tasting [237][83]. The raw materials and the processing methods used have a significant impact on the physiochemical properties of the final product. Therefore, it is very important to study these changes in newly formulated bakery products fortified with date components. Shelf life is another important factor because if a product can be stored for a longer period of time, the profits and efficiencies are also improved [238][84]. Storage conditions and hence shelf life of a product depend on the chemical composition, processing conditions, packaging and distribution of it [239][85]. Thus, it is quite helpful to have an idea of physical, chemical, nutritional and organoleptic properties and the shelf life of date-component-fortified bakery products.

References

- Jensen, H.H.; Kesavan, T.; Johnson, S.R. Measuring the impact of health awareness on food demand. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 1992, 14, 299–312.

- Hathwar, S.C.; Rai, A.K.; Modi, V.K.; Narayan, B. Characteristics and consumer acceptance of healthier meat and meat product formulations—A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 653–664.

- Salleh, H.S.; Noor, A.M.; Mat, N.H.N.; Yusof, Y.; Mohamed, W.N. Consumer-behavioural intention towards the consumption of functional food in Malaysia: Their profiles and behaviours. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2015, 14, 727–734.

- Zhou, W.; Hui, Y.H.; De Leyn, I.; Pagani, M.A.; Rosell, C.M.; Selman, J.D.; Therdthai, N. Bakery Products Science and Technology, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 1–761.

- Lončarić, R.; Tolušić, Z.; Kralik, I.; Gubić, B. Consumers’ attitudes towards bread and bakery products in East Croatia. In Proceedings of the 5th International congress Flour-Bread ’09, Osijek, Slavonia, 21–23 October 2009; pp. 361–368.

- Rosell, C.M.; Garzon, R. Chemical composition of bakery products. In Handbook of Food Chemistry; Cheung, P., Mehta, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 191–224.

- Abdul-Hamid, A.; Luan, Y.S. Functional properties of dietary fibre prepared from defatted rice bran. Food Chem. 2000, 68, 15–19.

- Ambigaipalan, P.; Shahidi, F. Date seed flour and hydrolysates affect physicochemical properties of muffin. Food Biosci. 2015, 12, 54–60.

- Martins, Z.E.; Pinho, O.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O. Food industry by-products used as functional ingredients of bakery products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 106–128.

- Kadam, S.U.; Prabhasankar, P. Marine foods as functional ingredients in bakery and pasta prducts. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1975–1980.

- Ubbink, J.; Krüger, J. Physical approaches for the delivery of active ingredients in foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 244–254.

- Dewettinck, K.; Van Bockstaele, F.; Kühne, B.; Van de Walle, D.; Courtens, T.M.; Gellynck, X. Nutritional value of bread: Influence of processing, food interaction and consumer perception. J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 48, 243–257.

- Caleja, C.; Barros, L.; Antonio, A.L.; Oliveira, M.B.P.; Ferreira, I.C. A comparative study between natural and synthetic antioxidants: Evaluation of their performance after incorporation into biscuits. Food Chem. 2017, 216, 342–346.

- Świeca, M.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Dziki, D.; Baraniak, B. Wheat bread enriched with green coffee—In Vitro bioaccessibility and bioavailability of phenolics and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1451–1457.

- Rosell, C.M.; Bajerska, J.; El Sheikha, A.F. (Eds.) Bread and Its Fortification: Nutrition and Health Benefits, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; p. 417.

- Hooda, S.; Jood, S. Organoleptic and nutritional evaluation of wheat biscuits supplemented with untreated and treated fenugreek flour. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 427–435.

- Lai, H.M.; Lin, T.C. Bakery products: Science and technology. In Bakery Products: Science and Technology; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 3–65.

- Brownlee, I.A. The physiological roles of dietary fibre. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 238–250.

- Sui, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W. Bread fortified with anthocyanin-rich extract from black rice as nutraceutical sources: Its quality attributes and in vitro digestibility. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 910–916.

- Al-Rasheed, N.M.; Attia, H.A.; Mohamad, R.A.; Al-Rasheed, N.M.; Al-Amin, M.A.; Al-Onazi, A. Aqueous date flesh or pits extract attenuates liver fibrosis via suppression of hepatic stellate cell activation and reduction of inflammatory cytokines, transforming growth factor-β1 and angiogenic markers in carbon tetrachloride-intoxicated rats. Evidence-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 247357.

- Diab, K.A.S.; Aboul-Ela, E. In Vivo comparative studies on antigenotoxicity of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) pits extract against DNA damage induced by N-Nitroso-N-methylurea in mice. Toxicol. Int. 2012, 19, 279.

- Kchaou, W.; Abbès, F.; Mansour, R.B.; Blecker, C.; Attia, H.; Besbes, S. Phenolic profile, antibacterial and cytotoxic properties of second grade date extract from Tunisian cultivars (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Food Chem. 2016, 194, 1048–1055.

- Al-Alawi, R.A.; Al-Mashiqri, J.H.; Al-Nadabi, J.S.M.; Al-Shihi, B.I.; Baqi, Y. Date palm tree (Phoenix dactylifera L.): Natural products and therapeutic options. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 845.

- Rahmani, A.H.; Aly, S.M.; Ali, H.; Babiker, A.Y.; Srikar, S. Therapeutic effects of date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera) in the prevention of diseases via modulation of anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and anti-tumour activity. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 483.

- Olaoye, O.A.; Onilude, A.A.; Idowu, O.A. Quality characteristics of bread produced from composite flours of wheat, plantain and soybeans. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 5, 1102–1106.

- Pacheco-Delahaye, E.; Testa, G. Nutritional, physical and sensory evaluation of wheat and green banana breads. Interscience 2005, 30, 300–304.

- Aljaloud, S.; Colleran, H.L.; Ibrahim, S.A. Nutritional value of date fruits and potential use in nutritional bars for athletes. Food Nutr. Sci. 2020, 11, 463.

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Fidan, H.; Aljaloud, S.O.; Stankov, S.; Ivanov, G. Application of date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruit in the composition of a novel snack bar. Foods 2021, 10, 918.

- Amin, A.; Abdel Fattah, A.F.; El kalyoubi, M.; El-Sharabasy, S. Quality attributes of Cookies Fortified with Date Powder. Arab Univ. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 27, 2539–2547.

- Noor Aziah, A.A.; Lee Min, W.; Bhat, R. Nutritional and sensory quality evaluation of sponge cake prepared by incorporation of high dietary fiber containing mango (Mangifera indica var. Chokanan) pulp and peel flours. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 62, 559–567.

- Al-Dalalia, S.; Zhenga, F.; Aleidc, S.; Abu-Ghoushd, M.; Samhourie, M.; Ammar, A.-F. Effect of dietary fibers from mango peels and date seeds on physicochemical properties and bread quality of Arabic bread. Int. J. Mod. Res. Eng. Manag. 2018, 1, 10–24.

- Masih, M.; Desale, T. Preparation of banana bread to utilize the over ripe banana. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 4, 30–33.

- Barrett, D.M.; Beaulieu, J.C.; Shewfelt, R. Color, flavor, texture, and nutritional quality of fresh-cut fruits and vegetables: Desirable levels, instrumental and sensory measurement, and the effects of processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 369–389.

- Schifferstein, H.N.J.; Wehrle, T.; Carbon, C.-C. Consumer expectations for vegetables with typical and atypical colors: The case of carrots. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 72, 98–108.

- Borchani, C.; Masmoudi, M.; Besbes, S.; Attia, H.; Deroanne, C.; Blecker, C. Effect of date flesh fiber concentrate addition on dough performance and bread quality. J. Texture Stud. 2011, 42, 300–308.

- Vergara-Valencia, N.; Granados-Pérez, E.; Agama-Acevedo, E.; Tovar, J.; Ruales, J.; Bello-Pérez, L.A. Fibre concentrate from mango fruit: Characterization, associated antioxidant capacity and application as a bakery product ingredient. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 722–729.

- Borchani, C.; Blecker, C.; Attia, H.; Masmoudi, M.; Besbes, S. Effect of date flesh fiber concentrate addition on bread texture. Turkish J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 10, 17–22.

- Romero-Lopez, M.R.; Osorio-Diaz, P.; Bello-Perez, L.A.; Tovar, J.; Bernardino-Nicanor, A. Fiber concentrate from orange (Citrus sinensis L.) bagase: Characterization and application as bakery product ingredient. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 2174–2186.

- Wani, A.A.; Sogi, D.S.; Singh, P.; Khatkar, B.S. Influence of watermelon seed protein concentrates on dough handling, textural and sensory properties of cookies. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 2139–2147.

- Vayalil, P.K. Date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera Linn): An emerging medicinal food. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 249–271.

- Gantait, S.; El-Dawayati, M.M.; Panigrahi, J.; Labrooy, C.; Verma, S.K. The retrospect and prospect of the applications of biotechnology in Phoenix dactylifera L. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 8229–8259.

- Guido, F.; Behija, S.E.; Manel, I.; Nesrine, Z.; Ali, F.; Mohamed, H.; Noureddine, H.A.; Lotfi, A. Chemical and aroma volatile compositions of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruits at three maturation stages. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1744–1754.

- AlFaris, N.A.; AlTamimi, J.Z.; AlGhamdi, F.A.; Albaridi, N.A.; Alzaheb, R.A.; Aljabryn, D.H.; Aljahani, A.H.; AlMousa, L.A. Total phenolic content in ripe date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 3566–3577.

- Lim, T.K. Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 371–380.

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Ayad, A.A.; Williams, L.L.; Ayivi, R.D.; Gyawali, R.; Krastanov, A.; Aljaloud, S.O. Date fruit: A review of the chemical and nutritional compounds, functional effects and food application in nutrition bars for athletes. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 1503–1513.

- El Hadrami, A.; Al-Khayri, J.M. Socioeconomic and traditional importance of date palm. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2012, 24, 371–385.

- Hussain, M.I.; Farooq, M.; Syed, Q.A. Nutritional and biological characteristics of the date palm fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.)—A review. Food Biosci. 2020, 34, 100509.

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Bahkali, A.H. Valorization of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) fruit processing by-products and wastes using bioprocess technology—Review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 20, 105–120.

- Al-Farsi, M.; Alasalvar, C.; Al-Abid, M.; Al-Shoaily, K.; Al-Amry, M.; Al-Rawahy, F. Compositional and functional characteristics of dates, syrups, and their by-products. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 943–947.

- Ahmed, I.A.; Ahmed, A.W.K.; Robinson, R.K. Chemical composition of date varieties as influenced by the stage of ripening. Food Chem. 1995, 54, 305–309.

- Al-Shahib, W.; Marshall, R.J. The fruit of the date palm: Its possible use as the best food for the future? Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2003, 54, 247–259.

- Mistrello, J.; Sirisena, S.D.; Ghavami, A.; Marshall, R.J.; Krishnamoorthy, S. Determination of the antioxidant capacity, total phenolic and avonoid contents of seeds from three commercial varieties of culinary dates. Int. J. Food Stud. 2014, 3, 34–44.

- Ghnimi, S.; Umer, S.; Karim, A.; Kamal-Eldin, A. Date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.): An underutilized food seeking industrial valorization. NFS J. 2017, 6, 1–10.

- Baliga, M.S.; Baliga, B.R.V.; Kandathil, S.M.; Bhat, H.P.; Vayalil, P.K. A review of the chemistry and pharmacology of the date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1812–1822.

- Habib, H.M.; Ibrahim, W.H. Nutritional quality evaluation of eighteen date pit varieties. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 99–111.

- Platat, C.; Habib, H.M. Identification of Date Seeds Varieties Patterns to Optimize Nutritional Benefits of Date Seeds. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, S8.

- Elgasim, E.A.; Alyousef, Y.A.; Humeid, A.M. Possible hormonal activity of date pits and flesh fed to meat animals. Food Chem. 1995, 52, 149–152.

- Ali, B.H.; Bashir, A.K.; Alhadrami, G. Reproductive hormonal status of rats treated with date pits. Food Chem. 1999, 66, 437–441.

- Al-Shahib, W.; Marshall, R.J. Fatty acid content of the seeds from 14 varieties of date palm Phoenix dactylifera L. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 38, 709–712.

- Al-Farsi, M.A.; Lee, C.Y. Nutritional and functional properties of dates: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 877–887.

- Besbes, S.; Blecker, C.; Deroanne, C.; Drira, N.-E.; Attia, H. Date seeds: Chemical composition and characteristic profiles of the lipid fraction. Food Chem. 2004, 84, 577–584.

- Hamada, J.S.; Hashim, I.B.; Sharif, F.A. Preliminary analysis and potential uses of date pits in foods. Food Chem. 2002, 76, 135–137.

- Sulieman, A.M.; Abd Elhafise, I.; Abdelrahim, A. Comparative study on five Sudanese date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruit cultivars. Food Nutri. Sci. 2012, 3, 1245–1251.

- Lieb, V.M.; Kleiber, C.; Metwali, E.M.R.; Kadasa, N.M.S.; Almaghrabi, O.A.; Steingass, C.B.; Carle, R. Fatty acids and triacylglycerols in the seed oils of Saudi Arabian date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) palms. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 1572–1577.

- Saafi, E.B.; Trigui, M.; Thabet, R.; Hammami, M.; Achour, L. Common date palm in Tunisia: Chemical composition of pulp and pits. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 2033–2037.

- Bouaziz, M.A.; Amara, W.B.; Attia, H.; Blecker, C.; Besbes, S. Effect of the addition of defatted date seeds on wheat dough performance and bread quality. J. Texture Stud. 2010, 41, 511–531.

- Alsafadi, D.; Ibrahim, M.I.; Alamry, K.A.; Hussein, M.A.; Mansour, A. Utilizing the crop waste of date palm fruit to biosynthesize polyhydroxyalkanoate bioplastics with favorable properties. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139716.

- Rambabu, K.; Bharath, G.; Banat, F.; Show, P.L. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Phoenix dactylifera waste as bioreductant for effective dye degradation and antibacterial performance in wastewater treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123560.

- Rambabu, K.; Bharath, G.; Hai, A.; Banat, F.; Hasan, S.W.; Taher, H.; Mohd Zaid, H.F. Nutritional quality and physico-chemical characteristics of selected date fruit varieties of the United Arab Emirates. Processes 2020, 8, 256.

- Al-Hamdani, H. The effect of eating date pomace on increasing hemoglobin levels in a sample of women. Plant Arch. 2019, 19, 1427–1433.

- Majzoobi, M.; Karambakhsh, G.; Golmakani, M.T.; Mesbahi, G.R.; Farahnaki, A. Chemical Composition and Functional Properties of Date Press Cake, an Agro-Industrial Waste. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 21, 1807–1817.

- Peter Ikechukwu, A.; Okafor, D.C.; Kabuo, N.O.; Ibeabuchi, J.C.; Odimegwu, E.N.; Alagbaoso, S.O.; Njideka, N.E.; Mbah, R.N. Production and evaluation of cookies from whole wheat and date palm fruit pulp as sugar substitute. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2017, 4, 1–31.

- Nwanekezi, E.C.; Ekwe, C.C.; Agbugba, R.U. Effect of substitution of sucrose with date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) fruit on quality of bread. J. Food Process. Technol. 2015, 6, 1.

- Bouaziz, F.; Abdeddayem, A.B.; Koubaa, M.; Ellouz Ghorbel, R.; Ellouz Chaabouni, S. Date seeds as a natural source of dietary fibers to improve texture and sensory properties of wheat bread. Foods. 2020, 9, 737.

- Platat, C.; Habib, H.M.; Hashim, I.B.; Kamal, H.; AlMaqbali, F.; Souka, U.; Ibrahim, W.H. Production of functional pita bread using date seed powder. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6375–6384.

- Basha, S.; Ahfaiter, H.; Zeitoun, A.M.; Abdalla, A.E. Physicochemical properties and nutritional value of Egyptian date seeds and its applications in some bakery products. J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2018, 23, 260–279.

- Yaseen, T.; ur-Rehman, S.; Ashraf, I. Development and nutritional evaluation of date bran muffins. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2012, 2, 2–5.

- Ahmed, J.; Almusallam, A.S.; Al-Salman, F.; AbdulRahman, M.H.; Al-Salem, E. Rheological properties of water insoluble date fiber incorporated wheat flour dough. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 51, 409–416.

- Salem, E.; Almohmadi, N.; Al-Khataby, N. Utilization of date seeds powder as antioxidant activities components in preparation of some baking products. J. Food Dairy Sci. 2011, 2, 399–409.

- Shokrollahi, F.; Taghizadeh, M. Date seed as a new source of dietary fiber: Physicochemical and baking properties. Int. Food Res. J. 2016, 23, 2419–2425.

- Vitali, D.; Dragojević, I.V.; Šebečić, B. Effects of incorporation of integral raw materials and dietary fibre on the selected nutritional and functional properties of biscuits. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1462–1469.

- Čukelj, N.; Novotni, D.; Sarajlija, H.; Drakula, S.; Voučko, B.; Ćurić, D. Flaxseed and multigrain mixtures in the development of functional biscuits. LWT 2017, 86, 85–92.

- Markovic, I.; Ilic, J.; Markovic, D.; Simonovic, V.; Kosanic, N. Color measurement of food products using CIE L* a* b* and RGB color space. J. Hyg. Eng. Des. 2013, 4, 50–53.

- Masson, M.; Delarue, J.; Blumenthal, D. An observational study of refrigerator food storage by consumers in controlled conditions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 294–300.

- Sharif, K.; Butt, M.S.; Anjum, F.M.; Nasir, M.; Minhas, R.; Qayyum, M.M. Extension of cookies shelf life by using rice bran oil. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2003, 5, 455–457.

More