Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Anthony Bonavia.

The serotonin syndrome is a medication-induced condition resulting from serotonergic hyperactivity, usually involving antidepressant medications. As the number of patients experiencing medically-treated major depressive disorder increases, so does the population at risk for experiencing serotonin syndrome. Excessive synaptic stimulation of 5-HT2A receptors results in autonomic and neuromuscular aberrations with potentially life-threatening consequences.

- serotonin syndrome

- polypharmacy

- antidepressant toxicity

- serotonin

- serotonin toxicity

1. Introduction

The serotonin syndrome (SS) is a clinical condition resulting from serotonergic over-activity at synapses of the central and peripheral nervous systems. The true incidence of the disease is unknown, given that its severity varies and that many of its symptoms may be common to other clinical conditions. The SS is triggered by therapeutic drugs that are not only common, but ones whose use appears to be increasing at an alarming rate [1]. The most common drug triggers of SS are antidepressants, for which the incidence of use in adults in the United States has increased from 6% in 1999 to 10.4% in 2010 [2]. Furthermore, reported ingestions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increased by almost 15% from 2002 to 2005 [3,4,5,6,7][3][4][5][6][7].

2. Clinical Context

2.1. Definition and Epidemiology

The diagnostic basis of SS includes the triad of altered mental status, autonomic hyperactivity, and neuromuscular abnormalities [8,9][8][9] in patients exposed to any medication which increases the activation of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) receptors in the body [10]. These medications include SSRIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI), opioid analgesics, antiemetics, illicit drugs, and others [10]. The widespread use of these medications puts a large portion of the population at risk for developing this disease, especially if used in combination [11]. A retrospective cohort study reviewing Veterans Health Administration records from 2009–2013 showed a disease incidence of 0.23% in patients exposed to serotonergic medications (0.07% overall) [12]. This same study also reported a 0.09% incidence of SS in commercially insured patients exposed to serotonergic medications in 2013 (0.03% overall) [12]. The median cost per inpatient hospital stay associated with SS was $10,792 for commercially insured patients and $8765 for Veterans Health Administration patients [12]. No associated mortality data was reported [10,12][10][12]. There are no reports identifying specific patient risk factors that are associated with the development of SS outside of the genetic polymorphisms that will be described in further detail later. However, many of the medications with the potential to cause SS are commonly used in the geriatric population, thus placing these patients at higher risk of developing the disorder.

Since SS varies in presentation, it is likely to be grossly underdiagnosed in clinical practice and, thus, studies into its precise mechanism are very limited [13]. Much of the relevant research data is derived from animal models and from case descriptions of individuals in whom the disease has been highly suspected.

2.2. Manifestations and Diagnosis

Several diagnostic algorithms have been proposed since SS was first recognized as a discrete disease entity (Table 1). The main challenges encountered in establishing formal diagnostic criteria are (1) the wide range of symptoms exhibited by patients affected by the disease and (2) the lack of a confirmatory laboratory test. Thus, the diagnosis of SS remains purely clinical at present. The first diagnostic criteria were proposed by Sternbach et al. in 1991, based on a review of 38 published case reports in which patients demonstrated several shared symptoms [8]. Cases were reported by as many as 12 different investigators, and the most commonly reported symptoms included confusion (n = 16), hypomania (n = 8), restlessness (n = 17), and myoclonus (n = 13) [8]. Sternbach’s criteria were based on the inclusion of three or more of the most commonly noted symptoms extracted from the 38 cases. The major weakness of Sternbach’s criteria was the inclusion of four separate altered mentation symptoms (confusion/hypomania, agitation, and incoordination), which made it possible to diagnose SS purely based on mental status changes [11]. Such mental status changes could be commonly observed in many other conditions such as alcohol and drug withdrawal states and anticholinergic delirium [3], a limitation which Sternbach fully acknowledged.

Table 1.

Comparison between the Sternbach, Radomski, and Hunter Criteria for diagnosing serotonin toxicity.

| Sternbach Criteria | Radomski Criteria | Hunter Criteria |

|---|

| Inclusion Criteria | Presence of serotonergic medication | Presence of serotonergic medication | Presence of serotonergic medication | |

| Exclusion Criteria | Presence of other possible disease etiologies (e.g., infection, substance abuse, and withdrawal) and/or recent addition (or increase in dose) of neuroleptic medication. |

None | None | |

| Signs and Symptoms | At least three of the following signs/symptoms: | Either four major, or three major plus two minor signs/symptoms: | Any of the following combinations of primary (1°) ± secondary (2°) signs/symptoms: | |

| Major: | ||||

| Mental status changes (confusion, hypomania) | Impaired consciousness | |||

| Elevated mood | ||||

| Agitation | Semicoma/coma | 1°: Spontaneous clonus alone | ||

| Myoclonus | ||||

| Myoclonus | Tremor | 1°: Inducible clonus AND | ||

| Shivering | ||||

| Hyperreflexia | Rigidity | 2°: Agitation or diaphoresis | ||

| Hyperreflexia | ||||

| Diaphoresis | Fever | 1°: Ocular clonus AND | ||

| Sweating | ||||

| Shivering | Minor: | 2°: Agitation or diaphoresis | ||

| Restlessness | ||||

| Tremor | Insomnia | 1°: Tremor AND | ||

| Incoordination | ||||

| Diarrhea | Dilated pupils | 2°: Hyperreflexia | ||

| Akathisia | ||||

| Incoordination | Tachycardia | 1°: Hypertonicity AND fever (temperature >38 °C) AND | ||

| Tachypnea/Dyspnea | ||||

| Fever | Diarrhea | 2°: Ocular clonus | or | inducible clonus |

| Hypertension/hypotension |

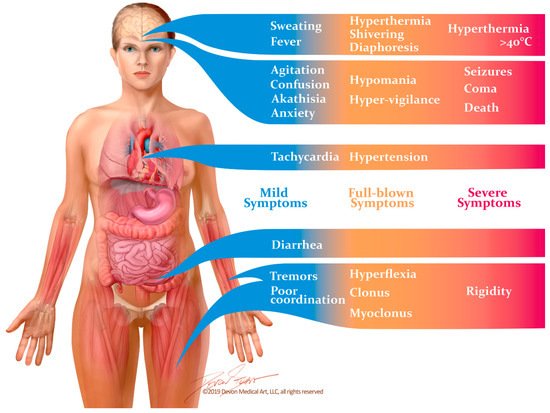

Between 1995 and 2000, Radomski and colleagues [14] reviewed subsequent cases of suspected SS with the goals of refining Sternbach’s diagnostic criteria and outlining the medical management of this disorder. The most recent diagnostic criteria, however, were developed by Dunkley et al. in 2003 [11]. Dunkley’s criteria were formed through the use of a toxicology database called the Hunter Area Toxicology Service, which included patients who were known to have overdosed on at least one serotonergic medication. A decision tree was constructed by including symptoms which recurred at a statistically significant frequency in patients with SS that had been diagnosed by a medical toxicologist. This diagnostic algorithm was both more sensitive (84% vs. 75%) and more specific (97% vs. 96%) in diagnosing SS than Sternbach’s criteria [11]. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria, as they are now known, are generally considered the gold standard for diagnosing this disease [10]. They consist of the aforementioned triad of altered mental status, neuromuscular excitation and autonomic dysfunction. Symptoms usually occur within one hour of exposure to triggering medications in 30% of patients, and within six hours in 60% of patients [1]. Mild cases may present as little more than flu-like symptoms, while severe cases may progress rapidly to cardiovascular collapse and death (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Signs and symptoms of the serotonin syndrome occur along a spectrum of severity. Mild symptoms may easily be overlooked, and may manifest as little more than diarrhea and flu-like symptoms. Unless the disease is recognized and the causative drugs are discontinued, it can rapidly progress to muscle rigidity, severe hyperthermia and death.

2.3. Differential Diagnosis

Several potentially life-threatening diseases share signs and symptoms similar to those present in SS, making the importance of an accurate and timely diagnosis imperative (Table 2). These diseases include neuroleptic malignant syndrome, anticholinergic toxicity, malignant hyperthermia [10], antidepressant discontinuation syndrome, and alcohol withdrawal. All may result in some degree of autonomic dysregulation (including tachycardia, hypertension, and hyperthermia) and an acutely altered mental status [10]. The first three of these disorders are most closely related, and their defining clinical features are summarized in Table 2 [10,15][10][15]. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is typically associated with the use of antipsychotic medications, such as dopamine antagonists, and presents with signs of muscular rigidity. These signs typically occur several days following exposure to triggering medications, unlike SS which immediately follows medication exposure [15]. Anticholinergic toxicity, as the name implies, is associated with the use of anticholinergic medications. Typical signs of this disorder include dry, hot skin and absent bowel sounds, contrasting with the diaphoresis and hyperactive bowel sounds that are typical of SS [10]. Malignant hyperthermia is associated with exposure to volatile anesthetic agents or to the depolarizing neuromuscular blocker, succinylcholine. The result is severe muscle rigidity and hyporeflexia [15].

Table 2.

Differential clinical diagnosis for serotonin syndrome.

| Disease | Medication Exposure | Shared Clinical Features | Distinguishing Clinical Features |

|---|

| Serotonin Syndrome | Serotonergic medications | Hypertension | Clonus, hyperreflexia Hyperactive bowel sounds |

| Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome | Dopamine antagonists | Tachycardia | No clonus or hyperreflexia Bradykinesia |

| Anticholinergic Toxicity | Acetylcholine antagonist | Hyperthermia | No clonus or hyperreflexia Dry skin Absent bowel sounds |

| Malignant Hyperthermia | Halogenated anesthetics Succinylcholine |

Altered mental Status | No clonus or hyperreflexia Extreme muscular rigidity |

Like alcohol withdrawal, benzodiazepine or barbiturate withdrawal can cause a hyperactive state which may be mistaken for SS. Alcohol, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates are central nervous system depressants, and their abrupt discontinuation in dependent patients may trigger a potentially life-threatening reaction. Alcohol withdrawal typically ranges in severity from disorientation and tremulousness to ‘delirium tremens’, which occurs within 48–72 h of the last alcoholic exposure and may be deadly. Delirium tremens, as the name implies, is characterized by disorientation and global confusion, hallucinations, and sometimes seizures [16][17]. Autonomic disturbances such as tachycardia and hypertension are common in severe cases although, unlike SS, hyperthermia is not [16][17]. The timing of benzodiazepine or barbiturate withdrawal varies depending on the medication half-life, and longer-acting medications are less likely to cause withdrawal symptoms [16][17]. Anxiety is common following benzodiazepine or barbiturate withdrawal, although hyperthermia and neuromuscular abnormalities (e.g., clonus and hyperreflexia) are not.

Withdrawal from antidepressant medications may also be mistaken for SS. Antidepressant withdrawal syndrome is typically associated with second-generation antidepressants [17][18], although it can also occur with SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) [18][19]. It usually begins within three days of stopping the offending medication, and symptoms are usually mild and resolve spontaneously within one to two weeks [19][20]. Antidepressant withdrawal syndrome can cause a spectrum of signs and symptoms including neuromuscular abnormalities such as akathisia, myoclonic jerks, and tremor, as well as altered mental status, psychosis, and mood disturbances. However, it is not typically associated with hyperthermia or with autonomic disturbances such as tachycardia [18][19].

3. The Molecular Basis for the Serotonin Syndrome

3.1. Animal Models

The exact pathophysiologic mechanism for SS has been difficult to elucidate, partially due to the multitude of known serotonin receptors classes and subtypes [21]. Although serotonin is the primary ligand for all of these receptors, only the stimulation of certain receptor subtypes leads to SS [21,22,23][21][22][23]. There is a dearth of research on the pathology of serotonin toxicity in humans, necessitating data collection from experimental animal models. Haberzettl et al. analyzed 109 publications in which rodent behavioral and autonomic responses were altered by the administration of serotonin agonists or serotonin-enhancing drugs [24]. Further, they identified “traditional behavioral responses,” a distinct set of rodent responses that are consistently observed following the administration of these medications and, thus, believed to be the rodent equivalent of SS in humans. These include, amongst others, forepaw treading, hindlimb abduction, head weaving, head twitching, back muscle contraction, and hyperthermia [8,22,24,25][8][22][24][25]. Haberzettl used these behaviors to assess the utility of standardized animal models of SS for the study of this disease in humans.

While the relevance of these rodent models remains questionable, animal models have, nonetheless, provided valuable insights into the importance of 5-HT receptors and the 5-HT transporter in the pathophysiology of SS. Until recently, SS was believed to be primarily a disease involving 5HT1A receptors [26], since the most prominent effects in the rodent serotonin behavioral syndrome appeared to be mediated by postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors [27,28,29,30,31][27][28][29][30][31]. Subsequent animal studies involving hyperthermia and muscle excitation have shed some more light on the potential pathophysiology of SS in humans. In these experiments, rats exposed to various serotonin receptor subtype-selective antagonists demonstrated hyperthermia that was significantly associated with 5-HT2A receptor stimulation [32]. Additionally, hyperthermia was prevented when rats exposed to a serotonin precursor and MAOI was introduced to the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ritanserin [33]. Conversely, when the 5-HT1A receptor was directly stimulated, rats develop hypothermia [28,34][28][34]. Although 5-HT2A stimulation would appear to be the cause of hyperthermia in SS, this is likely an over-simplification. Rat models of SS also show increased levels of norepinephrine, dopamine and glutamate within the hypothalamus [35,36][35][36], as well as elevated dopamine and norepinephrine levels in the frontal cortex of rats exposed to 5-HT2A agonists [37]. The N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist memantine, as well as positive allosteric modulators at GABAA, diazepam, and chlormethiazole, have all been found to be effective at decreasing the hyperthermic response in SS model rats. This suggests that, at least in rats, GABA and NMDA receptors are also involved in the pathogenesis of SS [33,38][33][38].

3.2. Molecular Pathways

An understanding of the putative mechanisms of SS necessitates a basic understanding of serotonin synthesis and clearance. 5-hydroxytryptamine is produced in enterochromaffin cells of the gastrointestinal tract as well as in the midline raphe nuclei of the brainstem. The serotonin produced in enterochromaffin cells is responsible for most of the neurohormone present in the blood, and of the approximately 10 mg of serotonin present in the human body, 4–8 mg is found in enterochromaffin cells located in the gastric and intestinal mucosa [26]. The remainder is found in the central nervous system and in platelets (where it is taken up and stored alone, since platelets do not synthesize serotonin) [26]. The serotonin produced in the gastrointestinal tract stimulates physiologic functions as diverse as vasoconstriction, uterine contraction, bronchoconstriction, gastrointestinal motility, and platelet aggregation. In contrast, centrally-released serotonin inhibits excitatory neurotransmission and modulates wakefulness, attention, affective behavior (anxiety and depression), sexual behavior, appetite, thermoregulation, motor tone, migraine, emesis, nociception, and aggression [10,39][10][39]. The signs and symptoms associated with SS include a conglomeration of effects produced by overzealous activation of central and peripheral serotonin receptors.

3.3. Genetic Polymorphisms

It appears that certain individuals with known polymorphisms at the T102C site of the 5-HT2A receptor gene may be predisposed to developing SS [20,53][16][40]. Over the last decade, genetic polymorphisms affecting the 5-HT2A receptor have also been implicated in antidepressant therapy failure and in the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders, ranging from schizophrenia to affective disorders [81][41]. A prospective, double-blind, randomized pharmacogenetic study compared treatment outcomes with the SSRI paroxetine and the non-SSRI antidepressant mirtazapine in patients having different T/C single nucleotide polymorphisms affecting the 5-HT2A receptor [82][42]. The study found that patients who are homozygous for polymorphisms at the HTR2A locus (C/C) are more likely to discontinue paroxetine due to more severe adverse side effects. Incidentally, mirtazapine has a unique mechanism of enhancing serotonergic and noradrenergic pathways in the central nervous system [83][43]. It inhibits presynaptic inhibitory receptors on noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons (thus, increasing release of these neurotransmitters in the synaptic cleft). However, since it also blocks 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors, only serotonergic transmission via 5-HT1A is enhanced [84][44]. Individual variations in serotonin metabolism by CYPs have also been proposed to contribute to SS susceptibility [86,87,88][45][46][47]. One case report describes the development of SS in an individual who was taking the SSRI paroxetine in the absence of other known serotonergic medications [87][46]. While paroxetine infrequently causes SS in isolation, this patient was found to have a polymorphism for the CYP2D6 allele, which may have impaired the metabolism of paroxetine and contributed to the development of SS [87][46]. A similar case report postulated that altered drug pharmacokinetics may have contributed to SS in a patient taking fluoxetine who was found to have a nonfunctioning CYP2D6 genotype, as well as being heterozygous for an allele of CYP2C19 that results in poor metabolizing ability [88][47]. The contribution of CYP polymorphisms to the development of SS is further complicated when one considers the multitude of pharmacologic CYP inducers and inhibitors in clinical use today. Medications for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are notorious for altering the intrinsic metabolic rates of CYPs. Indeed, one case describes the development of SS in an HIV-infected patient taking antiretroviral medications which are known inhibitors of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4. In addition to polypharmacy-induced alterations in CYP-driven drug metabolism, this patient was also found to express a poor metabolizer phenotype of CYP2D6 [86][45]. Unlike T102C polymorphisms, the CYP2D6 genotype has not yet been shown to alter tolerance to antidepressant medications, although large-scale studies are needed to establish the risk conferred by CYP polymorphisms on the development of SS [83][43]. As described above, SERT proteins are critical to the termination of synaptic serotonergic activity. Animal studies have suggested that genetic differences in the SERT gene may also partially explain the susceptibility of certain individuals to develop SS [83,89][43][48]. Fox et al. showed that SERT knockout mice (SERT-/-) exhibited increased susceptibility to SS-like behavior when given serotonergic drugs. Some of these mice even displayed SS-like behavior without administration of 5-HTP. This was also true in mice heterozygous for the gene (SERT+/-). However, in wild type mice (SERT+/+), administration of both 5-HTP and MAO-A-selective inhibitor was needed to induce SS-like behavior. Furthermore, knockout and heterozygous mice expressed significantly less presynaptic inhibitory Htr1a autoreceptors. These receptors direct a negative feedback mechanism, so that their activation by serotonin decreases serotonin synthesis and, conversely, fewer inhibitory receptors lead to increased serotonin synthesis. These findings in mice may have implications for patient care. SERT polymorphisms are known to exist in humans [90][49], and some can reduce SERT function by as much as 50% of normal levels. Further research is needed to assess whether they have a clinically meaningful impact in patients who develop SS.References

- Mason, P.J.; Morris, V.A.; Balcezak, T.J. Serotonin syndrome. Presentation of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine 2000, 79, 201–209.

- Mojtabai, R.; Olfson, M. National trends in long-term use of antidepressant medications: Results from the U.S. National health and nutrition examination survey. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 169–177.

- Uddin, M.F.; Alweis, R.; Shah, S.R.; Lateef, N.; Shahnawaz, W.; Ochani, R.K.; Dharani, A.M.; Shah, S.A. Controversies in serotonin syndrome diagnosis and management: A review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, OE05–OE07.

- Watson, W.A.; Litovitz, T.L.; Klein-Schwartz, W.; Rodgers, G.C., Jr.; Youniss, J.; Reid, N.; Rouse, W.G.; Rembert, R.S.; Borys, D. 2003 annual report of the american association of poison control centers toxic exposure surveillance system. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2004, 22, 335–404.

- Watson, W.A.; Litovitz, T.L.; Rodgers, G.C., Jr.; Klein-Schwartz, W.; Reid, N.; Youniss, J.; Flanagan, A.; Wruk, K.M. 2004 annual report of the american association of poison control centers toxic exposure surveillance system. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2005, 23, 589–666.

- Watson, W.A.; Litovitz, T.L.; Rodgers, G.C., Jr.; Klein-Schwartz, W.; Youniss, J.; Rose, S.R.; Borys, D.; May, M.E. 2002 annual report of the american association of poison control centers toxic exposure surveillance system. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2003, 21, 353–421.

- Lai, M.W.; Klein-Schwartz, W.; Rodgers, G.C.; Abrams, J.Y.; Haber, D.A.; Bronstein, A.C.; Wruk, K.M. 2005 annual report of the american association of poison control centers’ national poisoning and exposure database. Clin. Toxicol. 2006, 44, 803–932.

- Sternbach, H. The serotonin syndrome. Am. J. Psychiatry 1991, 148, 705–713.

- Martin, T.G. Serotonin syndrome. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1996, 28, 520–526.

- Boyer, E.W.; Shannon, M. The serotonin syndrome. New Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1112–1120.

- Dunkley, E.J.; Isbister, G.K.; Sibbritt, D.; Dawson, A.H.; Whyte, I.M. The hunter serotonin toxicity criteria: Simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM 2003, 96, 635–642.

- Nguyen, C.T.; Xie, L.; Alley, S.; McCarron, R.M.; Baser, O.; Wang, Z. Epidemiology and economic burden of serotonin syndrome with concomitant use of serotonergic agents: A retrospective study utilizing two large us claims databases. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2019, 19.

- Mackay, F.J.; Dunn, N.R.; Mann, R.D. Antidepressants and the serotonin syndrome in general practice. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 1999, 49, 871–874.

- Radomski, J.W.; Dursun, S.M.; Reveley, M.A.; Kutcher, S.P. An exploratory approach to the serotonin syndrome: An update of clinical phenomenology and revised diagnostic criteria. Med. Hypotheses 2000, 55, 218–224.

- Isbister, G.K.; Buckley, N.A.; Whyte, I.M. Serotonin toxicity: A practical approach to diagnosis and treatment. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 187, 361–365.

- Buckley, N.A.; Dawson, A.H.; Isbister, G.K. Serotonin syndrome. BMJ 2014, 348, g1626.

- Sellers, E.M. Alcohol, barbiturate and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndromes: Clinical management. CMAJ 1988, 139, 113–120.

- Wilson, E.; Lader, M. A review of the management of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 5, 357–368.

- Warner, C.H.; Bobo, W.; Warner, C.; Reid, S.; Rachal, J. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. Am. Fam. Physician. 2006, 74, 449–456.

- Haddad, P. Newer antidepressants and the discontinuation syndrome. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1997, 58, 17–21.

- Mills, K.C. Serotonin syndrome. A clinical update. Crit. Care Clin. 1997, 13, 763–783.

- Isbister, G.K.; Buckley, N.A. The pathophysiology of serotonin toxicity in animals and humans: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2005, 28, 205–214.

- Nisijima, K.; Yoshino, T.; Ishiguro, T. Risperidone counteracts lethality in an animal model of the serotonin syndrome. Psychopharmacology 2000, 150, 9–14.

- Haberzettl, R.; Bert, B.; Fink, H.; Fox, M.A. Animal models of the serotonin syndrome: A systematic review. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 256, 328–345.

- Kalueff, A.V.; Fox, M.A.; Gallagher, P.S.; Murphy, D.L. Hypolocomotion, anxiety and serotonin syndrome-like behavior contribute to the complex phenotype of serotonin transporter knockout mice. Genes. Brain Behav. 2007, 6, 389–400.

- Ener, R.A.; Meglathery, S.B.; Van Decker, W.A.; Gallagher, R.M. Serotonin syndrome and other serotonergic disorders. Pain Med. 2003, 4, 63–74.

- Darmani, N.A.; Ahmad, B. Long-term sequential determination of behavioral ontogeny of 5-ht1a and 5-ht2 receptor functions in the rat. J. Pharm. Exp. 1999, 288, 247–253.

- Goodwin, G.M.; Green, A.R. A behavioural and biochemical study in mice and rats of putative selective agonists and antagonists for 5-ht1 and 5-ht2 receptors. Br. J. Pharm. 1985, 84, 743–753.

- Forster, E.A.; Cliffe, I.A.; Bill, D.J.; Dover, G.M.; Jones, D.; Reilly, Y.; Fletcher, A. A pharmacological profile of the selective silent 5-ht1a receptor antagonist, way-100635. Eur. J. Pharm. 1995, 281, 81–88.

- Smith, L.M.; Peroutka, S.J. Differential effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine1a selective drugs on the 5-ht behavioral syndrome. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 1986, 24, 1513–1519.

- Tricklebank, M.D.; Forler, C.; Fozard, J.R. The involvement of subtypes of the 5-ht1 receptor and of catecholaminergic systems in the behavioural response to 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin in the rat. Eur J. Pharm. 1984, 106, 271–282.

- Mazzola-Pomietto, P.; Aulakh, C.; Wozniak, K.; Hill, J.; Murphy, D. Evidence that 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-2-aminopropane (doi)-induced hyperthermia in rats is mediated by stimulation of 5-ht2a receptors | springerlink. Psychopharmacology 2019, 117, 193–199.

- Nisijima, K.; Shioda, K.; Yoshino, T.; Takano, K.; Kato, S. Diazepam and chlormethiazole attenuate the development of hyperthermia in an animal model of the serotonin syndrome. Neurochem. Int. 2003, 43, 155–164.

- Gudelsky, G.A.; Koenig, J.I.; Meltzer, H.Y. Thermoregulatory responses to serotonin (5-ht) receptor stimulation in the rat. Evidence for opposing roles of 5-ht2 and 5-ht1a receptors. Neuropharmacology 1986, 25, 1307–1313.

- Nisijima, K.; Yoshino, T.; Yui, K.; Katoh, S. Potent serotonin (5-ht)(2a) receptor antagonists completely prevent the development of hyperthermia in an animal model of the 5-ht syndrome. Brain Res. 2001, 890, 23–31.

- Shioda, K.; Nisijima, K.; Yoshino, T.; Kato, S. Extracellular serotonin, dopamine and glutamate levels are elevated in the hypothalamus in a serotonin syndrome animal model induced by tranylcypromine and fluoxetine. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 28, 633–640.

- Gobert, A.; Millan, M.J. Serotonin (5-ht)2a receptor activation enhances dialysate levels of dopamine and noradrenaline, but not 5-ht, in the frontal cortex of freely-moving rats. Neuropharmacology 1999, 38, 315–317.

- Nisijima, K.; Shioda, K.; Yoshino, T.; Takano, K.; Kato, S. Memantine, an nmda antagonist, prevents the development of hyperthermia in an animal model for serotonin syndrome. Pharmacopsychiatry 2004, 37, 57–62.

- Dvir, Y.; Smallwood, P. Serotonin syndrome: A complex but easily avoidable condition. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2008, 30, 284–287.

- Cooper, J.; Newby, D.; Whyte, I.; Carter, G.; Jones, A.; Isbister, G. Serotonin toxicity from antidepressant overdose and its association with the t102c polymorphism of the 5-ht2a receptor. Pharm. J. 2014, 14, 390–394.

- Norton, N.; Owen, M.J. Htr2a: Association and expression studies in neuropsychiatric genetics. Ann. Med. 2005, 37, 121–129.

- Murphy, G.M., Jr.; Kremer, C.; Rodrigues, H.E.; Schatzberg, A.F. Pharmacogenetics of antidepressant medication intolerance. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1830–1835.

- Kasper, S.; Praschak-Rieder, N.; Tauscher, J.; Wolf, R. A risk-benefit assessment of mirtazapine in the treatment of depression. Drug Saf. 1997, 17, 251–264.

- Anttila, S.A.; Leinonen, E.V. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001, 7, 249–264.

- Hegazi, A.; Mc Keown, D.; Doerholt, K.; Donaghy, S.; Sadiq, S.T.; Hay, P. Serotonin syndrome following drug–drug interactions and cyp2d6 and cyp2c19 genetic polymorphisms inan hiv-infected patient. AIDS 2012, 26, 2417–2423.

- Kaneda, Y.; Kawamura, I.; Fujii, A.; Ohmori, T. Serotonin syndrome—‘potential’ role of the cyp2d6 genetic polymorphism in asians. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002, 5, 105–106.

- Piatkov, I.; Mann, G.; Jones, T.; McLean, M.; Gunja, N. Serotonin toxicity and cytochrome p450 poor metaboliser genotype patient case. J. Investig. Genom. 2017, 4, 1–5.

- Fox, M.A.; Jensen, C.L.; Gallagher, P.S.; Murphy, D.L. Receptor mediation of exaggerated responses to serotonin-enhancing drugs in serotonin transporter (sert)-deficient mice. Neuropharmacology 2007, 53, 643–656.

- Lesch, K.P.; Bengel, D.; Heils, A.; Sabol, S.Z.; Greenberg, B.D.; Petri, S.; Benjamin, J.; Muller, C.R.; Hamer, D.H.; Murphy, D.L. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 1996, 274, 1527–1531.

More