1. Introduction

As aromatic and volatile liquids obtained from different plants and their different parts, essential oils (EOs) have been regarded with great interest throughout human history

As aromatic and volatile liquids obtained from different plants and their different parts, essential oils (EOs) have been regarded with great interest throughout human history

. Many of them and/or their ingredients have an unexpectedly large range of applications based on their various properties, such as antimicrobial, anticancer, or antioxidant

. These biological activities depend on the chemical composition, which is primarily determined by the plant genotype, but also greatly influenced by numerous factors such as geographical origin or environmental and agronomic conditions

. In addition, these chemical changes are strongly induced by the growth stage, which leads to the optimization of the harvest time

. Thus, research nowadays has been focused on the factors contributing to this variety, which has led to different chemotypes and chemical races being described

.

Foeniculum vulgare Miller (FV, fennel), belonging to the Apiaceae family, is a glabrous, erect, glaucous green biennial or perennial plant that grows up to 2.5 m. Shiny and striate stems bear leaves that are more or less triangular in outline with filiform and acuminate lobes, while terminal umbels, formed by 12–25 tiny yellow flowers, give ovoid-oblong, sweet-tasting schizocarpic fruits up to 10 mm long

. It develops better in a mild climate, especially near the sea coast or on riverbanks, and grows better in drained, light, dry soil, with low acidity

. A wide range of bioactive compounds from this plant have been studied, with phenols, phenolic glycosides, and volatile aroma compounds, such as anethole, estragole, and fenchone, being reported as its major phytoconstituents

. The essential oil from fennel (FVEO) is often used as a flavoring agent but also as a constituent of various cosmetic and pharmaceutical products

. Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate FVEO’s composition from plant materials of different origins and have shown that the major constituents are phenylpropanoid derivatives and monoterpenoids

. In the majority of literature sources, the distillation process is restricted to 3 or 4 h. However, a recent report pointed out the importance of extending the duration up to 6 h, thus greatly influencing the FVEO composition and extraction yield, as well as biological activity

[2][4]. Following that study, a fractionated extraction procedure was applied to the fennel fruit material collected in Montenegro. Liquid and vapor phases of essential oil (EO) samples were analyzed by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) and Headspace-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (HS-GC/MS) techniques.

. Following that study, a fractionated extraction procedure was applied to the fennel fruit material collected in Montenegro. Liquid and vapor phases of essential oil (EO) samples were analyzed by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) and Headspace-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (HS-GC/MS) techniques.

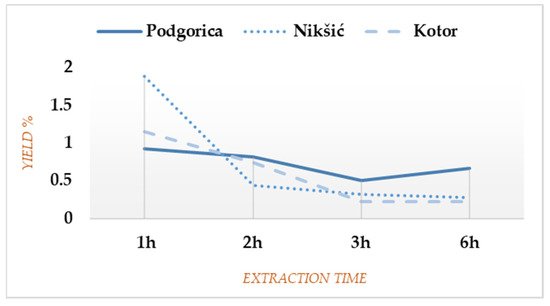

The overall dynamic by which FV gives EO is quite different for every plant sample, although certain similarities could be observed for Nikšić and Kotor since the main part of those EOs was extracted within the first 2 h (79.44% and 81.96% of the total yields, respectively). On the contrary, the material from Podgorica formed an almost uniform yield curve until the end of the extraction process (

), which was partly overlapping with the data previously reported

. The results confirm there is no a priori rule on the extraction time for obtaining EOs

. The application of a standard three-hour distillation would have never highlighted the observed trend. For comparison purposes, a search on the new EO portal Py-EO under development by one of the authors (

, accessed on 23 November 2021) revealed the presence of 36 FVEO compositions. Discarding 18 compositions published in the previous article

, most of the FVEO extractions were obtained by unfractionated hydro- and steam distillations with extraction times of 2, 3, 4, and 6 h and yields, ranging from 1.7 to 4.3%. No case was reported for FVEO from Montenegro. The FV plant materials were distilled either fresh or dried, and FVEO was extracted from different plant parts (fruits, leaves and full areal parts). In all listed EOs, the main constituents were found to be ANE, FEN, and EST (Table S3, Supplementary Materials).

Yield curves for Foeniculum vulgare Miller (FV) from three Montenegrin localities.

ANT and its isomer EST (also known as methyl chavicol) are very common ingredients of FVEO, usually present in fruits and flowers, as reported in numerous papers . These phenylpropanoids contribute a large component of the odor and flavor of many plants including Pimpinella anisum L.

, Artemisia dracunculus L.

, and Illicium verum Hook.f.

. ANE is responsible for the sweet, distinct, anise-like flavor characterizing FV fruits

. It is reported to exhibit antimicrobial, anthelmintic, insecticidal, gastroprotective, antithrombotic, spasmolytic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antinociceptive properties

. Regarding the FVEO samples analyzed in this study, ANE can be considered as the most characterizing compound since it was present in each fraction from all the localities. It was recognized at its highest level for EO obtained from Podgorica strongly defining this chemotype (up to 89.5%). Moreover, it significantly determined the last fraction’s composition of each extraction. EST, on the other side, was characteristic of the samples from Podgorica, although never present in a large amount.

FEN is an irregular bicyclic monoterpene ketone. The same as ANE, it is one of the common constituents of FVEO

. Moreover, it is also a characterizing compound in the samples included in this study, always being present in a considerable amount. FEN diminished with the extraction progress; therefore, it is most abundant in its first 2 h. Comparing the localities, the higher FEN content for the samples from Nikšić and Kotor could be noted. As a source of bitterness in fennel, this monoterpene seems to be responsible for the antifungal and acaricidal activity of its EO

, and it is reported to have analgesic

and anti-inflammatory properties

. It is a constituent of many other plants, including Thuja, Lavandula, and Artemisia species

.

TER is a volatile monoterpenoid alcohol that occurs in a large number of EOs. It is one of five isomers, being the most common one found in nature, along with terpinen-4-ol. It is a very important constituent of several species, such as Thymus caespititius Brot.

, Salvia libanotica Boiss. & Gaills

, and Melaleuca alternifolia (Maiden & Betche) Cheel

. TER attracts a great interest as it has a wide range of biological applications as an antioxidant

, and antinociceptive compound

. It is frequently used in perfumes and cosmetics because of its pleasant odor

. The compound occurs only in the samples from Nikšić and Kotor, always among the main ones (up to 56.5%). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report of such a high amount of TER. Along with FEN, it notably augments the fraction of monoterpenoids in these samples. In this regard, the opposite evolution (with the extraction development) of these two compounds can be observed, although always with the prevalence of TER (particularly evident in the second half of extraction).

The literature survey has revealed plenty of data. As a well-known industrial aromatic plant with different food and pharmaceutical applications, FV is thoroughly investigated. Thus, much research has been conducted so far to investigate its chemical composition. The results differ greatly depending on harvest time, region, and plant part, among other factors

. Some authors pointed out the FVEO composition is mostly dependent on the maturation period

. Generally, phenylpropanoid derivatives ANE and EST and monoterpenoids α-phellandrene, α-pinene, limonene, and FEN are usually reported as the main characterizing compounds

. The prevalence of monoterpenoids over the fraction of phenylpropanoids in the vegetative parts of FV can be considered as some general characteristic

. Contrary to that, EO obtained from fennel fruits is commonly characterized by the prevalence of the phenylpropanoid fraction, the presence of which is a stable characteristic, not dependent on origin

. The authors distinguished three intraspecific chemovarieties: FEN-rich, ANE-rich and EST-rich. Another study resulted in two different fruit-oil chemotypes: FEN-EST and FEN-ANE

. Phenylpropanoid content appeared to be associated with varieties, since azoricum and dulce were found to contain mostly ANE, while EST was found in prevalence in the vulgare variety

. All these analyses are in accordance with the results obtained for the samples from Podgorica (F1–F4) presented herein (

). Undoubtedly, the FVEO from Podgorica belongs to the ANE chemotype. In addition, a comparison with the results from the previous report showed certain similarities

. In that study, a 24-h fractionated steam distillation procedure was applied to the FV material from Italy (Tarquinia, Viterbo) and was monitored for 3 months, including vegetative and reproductive stages. A great increase in EO yield (up to 5 times) was noticed in October (fruiting material, the only one comparable with the results presented herein), as well as a substantial difference in EO composition. EST was identified as the highest-level main constituent for those EO samples, being particularly abundant in the first 6 h (up to 57.6%), accompanied by a significant amount of FEN (up to 14.1%). A gradual decrease with the extraction duration was observed for both of these compounds. This trend can be equated with FVEOs from Podgorica, although the EST content in the samples from Italy was drastically larger.

Chemical composition (%) of FV essential oils (FVEOs) from Podgorica analyzed by GC/MS and HS-GC/MS.

| N° |

Component |

|---|

| 1 |

|---|

| LRI |

| lit 2 |

|---|

| LRI |

| 3 |

|---|

| LRI |

| 4 |

|---|

| F1 |

F1HS |

F2 |

F2HS |

F3 |

F3HS |

F4 |

F4HS |

Linear Retention indices measured on apolar column. -: Traces < 0.1%.

Chemical profiles of the EO samples from Nikšić (F5-F8) and Kotor (F9–F12), however, cannot be related to any of those already reported (); this is primarily because of the high amount of TER (from 32.1% to 56.5%). This monoterpenoid, always accompanied by the lower amount of FEN, is combined with a significant amount of the phenylpropanoid ANE (up to 49.5%). Still, there is a slight difference between these localities: Whereas the samples from Kotor are quite rich in ANE, the ones from Nikšić are characterized by the prevalence of the monoterpene fraction. Accordingly, a new chemotype from Montenegro rich in TER can be defined.

Chemical composition (%) of FVEOs from Nikšić analyzed by GC/MS and HS-GC/MS.

| N° |

Component | 1 |

LRI | lit 2 |

LRI | 3 |

LRI | 4 |

F5 |

F5HS |

F6 |

F6HS |

F7 |

F7HS |

F8 |

F8HS |

Elution order on polar column.

Linear Retention indices from literature.

Linear Retention indices measured on polar column.

Linear Retention indices measured on apolar column. -: Traces < 0.1%.

Chemical composition (%) of FVEOs from Kotor analyzed by GC/MS and HS-GC/MS.

| 1 |

| α-pinene |

1021 |

1018 |

933 |

- |

- |

- |

1.5 |

- |

0.5 |

- |

2.4 |

| 2 |

| camphene |

camphene1063 |

| 2 |

camphene |

1063 | 1060 |

944 |

1063 |

1060- |

- |

- |

- |

944- |

- |

0.5 |

- |

0.1- |

- |

0.2 |

| - |

1060 | 0.1 |

- |

- |

944 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

β-pinene |

1108 |

1100 |

980 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.2 |

| 3 |

β-pinene |

1108 |

1100 |

980 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

- |

| 3 |

β-pinene |

1108 | - |

1100 |

980 |

- |

- | - |

- |

- |

- |

-- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

β -myrcene |

1160 |

1155 |

984 |

- |

0.5 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

- |

1.7 |

0.2 |

3.4 |

| 4 |

β-myrcene |

1160 |

1155 |

984 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

0.4 |

- |

1.3 |

5 |

α-phellandrene |

1177 |

1173 |

1004 |

0.2 |

3.4 |

0.3 |

4.5 |

0.2 |

3.5 |

0.3 |

5.5 |

| - |

0.1 |

| 2.1 |

- |

1.1 |

| 5 |

α-phellandrene |

1177 |

1173 |

1004 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

0.4 |

3.2 |

0.1 |

1.1 |

- |

1.0 |

6 |

limonene |

1198 |

1200 |

986 |

0.1 |

2.0 |

0.3 |

3.7 |

0.3 |

3.9 |

0.4 |

| 6 | 6.4 |

| limonene |

1198 |

1200 |

986 |

0.3 |

2.1 |

0.8 |

4.5 |

0.3 |

2.5 |

0.3 |

7 |

β-phellandrene |

1205 |

1206 |

1026 |

terpinolene |

1282 |

1284 |

1078 |

- |

| 4 |

- |

- |

0.2 |

- |

0.2 |

- |

0.4 |

| β-myrcene |

1160 |

1155 |

984 |

0.4 |

1.9 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

0.3 |

2.7 |

3.6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.5 |

| 7 |

β-phellandrene |

1205 |

1206 |

1026 |

- |

0.4 |

- |

0.6 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

0.1 |

8 |

1,8-cineole |

1209 |

1211 |

998 |

0.6 |

2.7 |

0.4 |

2.2 |

0.4 |

2.5 |

0.4 |

2.3 |

12 |

fenchone |

1422 |

1420 |

1082 |

9.1 |

24.5 |

7.5 |

32.7 |

5.1 |

26.8 |

3.4 |

15.9 |

| 13 |

fenchyl acetate |

1470 |

1465 |

1210 |

0.2 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 14 |

camphor |

1507 |

1501 |

1135 |

0.2 |

- |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

| 15 |

terpinen-4-ol |

1603 |

1601 |

1175 |

0.6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 16 |

estragole |

1655 |

1658 |

1178 |

6.4 |

10.4 |

6.1 |

7.6 |

5.8 |

7.7 |

5.1 |

6.4 |

| 0.3 |

2.9 |

| - |

| 5 |

α-phellandrene |

1177 |

1173 |

1004 |

0.2 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

- |

0.8 |

| 6 |

limonene |

1198 |

1200 |

986 |

0.5 |

2.4 |

0.6 |

3.4 |

0.8 |

5.2 |

0.9 |

6.1 |

| 7 |

β-phellandrene |

1205 |

1206 |

1026 |

- |

0.4 |

- |

- |

- |

0.28 |

1,8-cineole |

1209 |

1211 |

| 8 |

1,8-cineole |

1209 |

1211 | 998 |

0.2 |

1.6 |

0.4 |

9984.5 |

0.5 |

3.3 |

0.7 |

3.90.3 |

4.0 |

0.4 |

5.2 |

| 0.2 |

1.9 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

9 |

γ-terpinene |

1243 |

1242 |

1071 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

0.4 |

9 |

γ-terpinene |

1243 |

1242 |

1071 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

0.4 |

1.5 |

0.4 |

2.2 |

0.5 |

2.5 |

| 9 |

γ-terpinene |

1243 |

1242 |

1071 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

0.5 | 3.6 |

0.4 |

4.7 |

0.6 |

2.57.1 |

| 0.3 |

2.1 |

0.3 |

2.8 |

10 |

p-cymene |

1268 |

1271 |

1030 |

0.2 |

2.4 |

0.1 |

1.3 |

- |

0.8 |

- |

1.1 |

| 10 |

p-cymene |

1268 |

1271 |

1030 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

- |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

- |

| 10 | 0.3 |

| p-cymene |

1268 |

1271 |

1030 |

0.3 |

1.7 |

0.1 |

0.6 |

- |

0.4 |

- |

0.4 |

11 |

11 |

terpinolene |

1282 |

1284 |

1078 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

| 11 |

terpinolene |

1282 |

1284 |

1078 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

0.2 |

- |

0.3 |

- |

0.4 |

12 |

fenchone |

1422 |

1420 |

1082 |

30.9 |

62.0 |

19.2 |

50.6 |

16.9 |

43.0 |

10.9 |

29.1 |

| 12 |

fenchone |

1422 |

1420 |

1082 |

17.8 |

53.0 |

16.4 |

42.4 |

10.7 |

34.4 |

7.1 |

13 |

fenchyl acetate |

1470 |

1465 |

1210 |

0.2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 30.1 |

| 13 |

fenchyl acetate |

1470 |

1465 |

1210 |

0.2 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

- |

- |

14 |

camphor |

1507 |

1501 |

1135 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

| 14 |

camphor |

1507 |

1501 |

1135 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

15 |

terpinen-4-ol |

1603 |

1601 |

1175 |

- |

- |

0.1 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

0.2 |

| 15 | - |

| terpinen-4-ol |

1603 |

1601 |

1175 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.1 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

16 |

estragole |

1655 |

1658 |

1178 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 16 |

estragole |

1655 |

1658 |

1178 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

17 |

α-terpineol |

1729 |

1730 |

1190 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 17 |

α-terpineol |

1729 |

1730 |

1190 |

43.1 |

20.9 |

49.6 |

32.9 |

53.9 |

36.5 |

56.5 |

45.3 |

| 17 |

α-terpineol |

1729 |

1730 |

1190 |

32.1 |

23.1 |

36.1 |

26.9 |

41.5 |

40.2 |

42.2 |

52.5 |

18 |

anethole |

1837 |

1840 |

1260 |

82.7 |

53.5 |

84.5 |

38.2 |

87.8 |

45.7 |

89.5 |

1845.1 |

| anethole |

1837 |

1840 |

1260 |

22.8 |

3.3 |

28.0 |

5.4 |

26.5 |

5.5 |

30.0 |

9.5 |

| 18 |

anethole |

1837 |

1840 |

1260 |

47.7 |

10.7 |

43.8 |

10.5 |

46.4 |

15.5 |

49.5 |

5.4 |

Total (%) |

|

|

|

|

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

99.9 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| Total (%) |

|

|

|

|

99.9 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

99.7 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

99.8 |

Monoterpenoids |

|

|

|

|

9.3 |

| Total (%) |

|

|

|

|

99.9 |

99.9 |

99.7 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

99.9 |

99.9 |

100.0 |

26.1 |

7.9 |

37.2 |

5.4 |

30.8 |

3.8 |

21.1 |

| Monoterpenoids |

|

|

|

|

31.5 |

64.7 |

19.6 |

52.8 |

17.3 |

45.5 |

11.3 |

| Monoterpenoids | 31.4 |

| |

|

|

|

18.3 |

56.3 |

17.5 |

46.3 |

10.9 |

36.3 |

7.3 |

32.2 |

Monoterpenes |

|

|

|

|

0.3 |

4.6 |

0.6 |

6.8 |

0.4 |

7.4 |

0.8 |

12.0 |

| Monoterpenes |

|

|

|

|

0.7 |

3.8 |

0.6 |

3.7 |

0.9 |

5.5 |

0.9 |

6.2 |

Monoterpenes alcohol |

|

| Monoterpenes |

|

|

|

|

0.6 |

3.9 |

1.0 |

5.4 |

0.3 |

3.9 |

0.3 |

4.9 |

|

|

|

0.6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Monoterpenes alcohol |

|

|

|

|

43.1 |

20.9 |

49.7 |

32.9 |

54.0 |

36.5 |

56.7 |

45.3 |

| Monoterpenes alcohol |

|

|

|

|

32.1 |

23.1 |

36.1 |

26.9 |

41.6 |

40.2 |

42.3 |

Monoterpenes cyclic |

|

|

|

|

0.1 |

5.4 |

0.6 |

9.7 |

Monoterpenes cyclic |

|

|

|

|

0.3 |

6.7 |

1.5 |

4.40.5 |

7.9 |

0.7 |

15.2 |

| Others |

| 2 | 0.9 |

6.6 |

0.9 |

7.1 |

| 52.5 |

| Monoterpenes cyclic |

|

|

|

|

0.5 |

5.3 |

1.2 |

10.5 |

0.4 |

3.7 |

0.3 |

4.7 |

|

|

|

|

89.5 |

63.9 |

90.9 |

46.3 |

93.7 |

53.8 |

94.7 |

Others51.7 |

Elution order on polar column.

Linear Retention indices from literature.

Linear Retention indices measured on polar column.

Elution order on polar column.

Linear Retention indices from literature.

Linear Retention indices measured on polar column.

Intraspecific chemical polymorphism is quite common in aromatic plants. It depends on a combination of factors related to the environment and genetics, as well as the anatomical and physiological characteristics of plants. These factors are difficult to verify, so the existence of different chemotypes is often not clearly related to the possible causes

Linear Retention indices measured on apolar column. -: Traces < 0.1%.

Intraspecific chemical polymorphism is quite common in aromatic plants. It depends on a combination of factors related to the environment and genetics, as well as the anatomical and physiological characteristics of plants. These factors are difficult to verify, so the existence of different chemotypes is often not clearly related to the possible causes

. Keeping in mind the significant climatic and geographic differences between the three selected localities, a certain relationship between chemical variations and habitats can be suggested. However, additional ecological and eco-physiological analyses are needed.

The study presented herein also included the vapor phase analysis. The samples were characterized by an increase in the monoterpene fraction, mainly represented by FEN and TER. The percentages of FEN were particularly higher: Up to 4 times than the ones reported in the liquid phases, even 5 times in some fractions of FVEO from Podgorica (F3HS). However, some other minor compounds enhanced their amounts with vaporizing, such as α-phellandrene (5, up to 5.5%), limonene (6, up to 6.4%), 1,8-cineole (8, up to 5.2%), and γ-terpinene (9, up to 7.1%). Whereas the samples from Podgorica were still abundant in phenylpropanoids (with ANE being in prevalence over EST), the ones from Nikšić and Kotor were significantly deprived of this fraction.

A search of the literature available has revealed little data regarding this type of analysis. However, while FVEO’s vapor phase has not been analyzed, the headspace aroma of certain FV organs has. Thus, an analysis on the azoricum variety included bulbs and aerial parts material from Egypt, Spain, and Holland. The analysis showed that monoterpenes prevailed in most headspace matrices, with an abundance of 6 (up to 61.54%) followed by a significant amount of ANE, particularly in the Egyptian samples

. Further, another study included a comprehensive aroma profiling amongst FV fruit accessions of various origins reporting the predominance of ANE, particularly in the vulgare variety. Additionally, an azoricum variety accession from Austria was rich in EST and FEN as well

.

The volatile analysis of the FVEO samples presented herein revealed chemical profiles quite different from the corresponding ones in the liquid phases, generally with much higher amounts of low-boiling components and smaller amounts of the heaviest ones (Figures S1–S6, Supplementary Materials). Moreover, the headspace injection allowed the identification of some constituents ( 7) not found with the liquid phase analysis, thus highlighting the capability of this technique of minor compounds detection. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this analysis has been the pioneer for FVEO.

Bearing in mind the great influence of the chemical composition on the biological properties, as well as the effects of synergism and/or antagonism between the main and/or minor compounds, various further investigations can be suggested. In that sense, FVEO samples from Nikšić and Kotor abundant in TER have a priority of importance due to the numerous biological applications of this monoterpenoid.

) not found with the liquid phase analysis, thus highlighting the capability of this technique of minor compounds detection. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this analysis has been the pioneer for FVEO.

Bearing in mind the great influence of the chemical composition on the biological properties, as well as the effects of synergism and/or antagonism between the main and/or minor compounds, various further investigations can be suggested. In that sense, FVEO samples from Nikšić and Kotor abundant in TER have a priority of importance due to the numerous biological applications of this monoterpenoid.